Abstract

Comparisons of well-being indicators in monetary terms across regions of a country do not provide insights into actual differences in well-being. The reason is variability of price levels across regions, especially in large countries like Russia. Thus, the indicators should be adjusted to the regional price levels, which, in turn, poses a problem of estimating such levels. In Russia, official data on price levels (termed cost-of-living indices) are available; however, they are by city/town rather than by region, so being unsuitable for regional studies. This paper describes the methodology of aggregating the city cost-of-living indices to the regional ones and presents the results obtained for 2016–2020. These results serve as a mean for estimation of price-adjusted regional incomes per capita (regional real incomes). As can be expected, taking account of regional costs of living smooths to some extent the pattern of regional inequality. A comparison of the European and Asian parts of Russia suggests that real income per capita in the latter permanently remains lower than in the former.

Keywords: spatial price index, regional price level, cross-region income comparison, price-adjusted income

INTRODUCTION

Comparisons of well-being indicators in monetary terms (such as personal income, household consumption, wage, poverty line, etc.) between regions of a country do not provide insights into actual differences in well-being. The purchasing power of the national currency varies across regions, resulting in different levels of consumption provided by the same amount of money. This problem is especially severe in large countries, where local price levels can vary widely. For instance, the maximum to minimum ratio of the city cost of living in 2018 was 2.0 in the US (Campbell, 2021, Table 2) and 2.4 in Russia.1 Thus, to make a comparison between regions or cities adequate, their indicators should be adjusted to the respective price levels, also referred to as spatial price indices, spatial adjustment factors, sub-national PPPs, and cost-of-living indices (COLI).

Table 2. .

COLI by region, % (Russia as a whole = 100%)

| Region | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European part of Russia | |||||

| 1. Belgorod oblast | 85 | 84 | 86 | 86 | 86 |

| 2. Bryansk oblast | 94 | 94 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| 3. Vladimir oblast | 98 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 99 |

| 4. Voronezh oblast | 93 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 |

| 5. Ivanovo oblast | 98 | 98 | 99 | 97 | 97 |

| 6. Kaluga oblast | 98 | 99 | 98 | 98 | 97 |

| 7. Kostroma oblast | 92 | 92 | 91 | 90 | 95 |

| 8. Kursk oblast | 88 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 89 |

| 9. Lipetsk oblast | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 89 |

| 10. Moscow oblast | 107 | 108 | 109 | 109 | 109 |

| 11. Oryol oblast | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 91 |

| 12. Ryazan oblast | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 |

| 13. Smolensk oblast | 100 | 100 | 101 | 100 | 100 |

| 14. Tambov oblast | 89 | 88 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| 15. Tver oblast | 98 | 97 | 97 | 96 | 96 |

| 16. Tula oblast | 94 | 95 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| 17. Yaroslavl oblast | 99 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 99 |

| 18. Moscow | 127 | 127 | 127 | 129 | 128 |

| 19. Republic of Karelia | 106 | 106 | 109 | 108 | 109 |

| 20. Komi Republic | 108 | 109 | 109 | 110 | 109 |

| 21. Arkhangelsk oblast (without autonomous okrug) | 109 | 110 | 109 | 107 | 108 |

| 22. Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 154 | 151 | 148 | 141 | 139 |

| 23. Vologda oblast | 105 | 104 | 103 | 101 | 103 |

| 24. Kaliningrad oblast | 104 | 104 | 104 | 103 | 104 |

| 25. Leningrad oblast | 103 | 104 | 104 | 104 | 104 |

| 26. Murmansk oblast | 120 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 122 |

| 27. Novgorod oblast | 93 | 94 | 96 | 97 | 97 |

| 28. Pskov oblast | 99 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 98 |

| 29. St. Petersburg | 110 | 111 | 112 | 112 | 113 |

| 30. Republic of Adygeya | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| 31. Republic of Kalmykia | 84 | 85 | 91 | 92 | 92 |

| 32. Republic of Crimea | 96 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 98 |

| 33. Krasnodar krai | 101 | 101 | 102 | 102 | 102 |

| 34. Astrakhan oblast | 95 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 95 |

| 35. Volgograd oblast | 93 | 93 | 92 | 91 | 91 |

| 36. Rostov oblast | 98 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 97 |

| 37. Sevastopol | 95 | 101 | 101 | 104 | 104 |

| 38. Republic of Dagestan | 90 | 89 | 90 | 88 | 90 |

| 39. Republic of Ingushetia | 74 | 72 | 74 | 75 | 76 |

| 40. Kabardino-Balkarian Republic | 90 | 90 | 90 | 88 | 89 |

| 41. Karachay-Cherkess Republic | 94 | 94 | 93 | 91 | 92 |

| 42. Republic of Northern Ossetia–Alania | 91 | 90 | 90 | 88 | 88 |

| 43. Chechen Republic | 86 | 85 | 89 | 87 | 86 |

| 44. Stavropol krai | 92 | 93 | 96 | 96 | 97 |

| 45. Republic of Bashkortostan | 93 | 94 | 95 | 95 | 94 |

| 46. Republic of Mari El | 88 | 88 | 89 | 89 | 88 |

| 47. Republic of Mordovia | 86 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 86 |

| 48. Republic of Tatarstan | 90 | 89 | 90 | 89 | 90 |

| 49. Udmurt Republic | 94 | 93 | 92 | 93 | 94 |

| 50. Chuvash Republic | 89 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| 51. Perm krai | 99 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 100 |

| 52. Kirov oblast | 94 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 93 |

| 53. Nizhny Novgorod oblast | 99 | 100 | 101 | 100 | 100 |

| 54. Orenburg oblast | 88 | 88 | 89 | 89 | 88 |

| 55. Penza oblast | 88 | 88 | 89 | 88 | 89 |

| 56. Samara oblast | 97 | 95 | 95 | 92 | 93 |

| 57. Saratov oblast | 88 | 88 | 87 | 87 | 88 |

| 58. Ulyanovsk oblast | 93 | 94 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| 59. Kurgan oblast | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| 60. Sverdlovsk oblast | 102 | 102 | 101 | 100 | 98 |

| 61. Chelyabinsk oblast | 90 | 87 | 89 | 90 | 90 |

| Asian part of Russia | |||||

| Siberia | |||||

| 62. Altai Republic | 109 | 108 | 105 | 104 | 104 |

| 63. Tyva Republic | 96 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 |

| 64. Republic of Khakassia | 92 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 94 |

| 65. Altai krai | 89 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 92 |

| 66. Krasnoyarsk krai | 104 | 103 | 103 | 103 | 103 |

| 67. Irkutsk oblast | 97 | 95 | 95 | 96 | 96 |

| 68. Kemerovo oblast | 88 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 89 |

| 69. Novosibirsk oblast | 101 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 98 |

| 70. Omsk oblast | 85 | 85 | 85 | 88 | 89 |

| 71. Tomsk oblast | 98 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 100 |

| 72. Tyumen oblast (without autonomous okrugs) | 102 | 103 | 102 | 100 | 100 |

| 73. Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug | 121 | 119 | 119 | 117 | 116 |

| 74. Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 126 | 126 | 124 | 120 | 118 |

| Russian Far East | |||||

| 75. Republic of Buryatia | 97 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 |

| 76. Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) | 127 | 129 | 131 | 131 | 130 |

| 77. Zabaykalsky krai | 100 | 100 | 100 | 101 | 103 |

| 78. Kamchatka krai | 160 | 158 | 155 | 152 | 149 |

| 79. Primorsky krai | 119 | 116 | 115 | 115 | 116 |

| 80. Khabarovsk krai | 126 | 124 | 122 | 124 | 123 |

| 81. Amur oblast | 108 | 104 | 105 | 105 | 107 |

| 82. Magadan oblast | 141 | 141 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| 83. Sakhalin oblast | 129 | 126 | 124 | 124 | 126 |

| 84. Jewish Autonomous oblast | 111 | 110 | 110 | 111 | 113 |

| 85. Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | 158 | 158 | 164 | 165 | 158 |

Numerous researches constructing such indicators, as either a goal or a tool for adjustment of regional monetary indicators, can be found in the literature. Reviews due to Biggeri and Tiziana (2014), Aten (2017), and Weinand and Auer (2020) suggest that not only academic researchers, but also official statistical bodies do this work. Lacking data on regional price levels, some researchers apply rough proxies such as housing prices. For instance, Beenstock and Felsenstein (2007) used them for cross-region comparisons in Israel; Li and Gibson (2014) exploited this method for China. Sometimes, regional consumer price indices (CPI) are exploited for inter-regional comparisons.2

Although official statistical bodies in some countries try to estimate spatial price indices, this work is for the most part experimental and nonrecurrent. Countries where regular official data on local price levels are available are still few in number. In the US, the Council for Community and Economic Research (C2ER) produces and publishes quarterly COLI (formerly known as the “ACCRA cost-of-living index”) across about 300 cities. This index is the cost of a basket of 57 goods and services (with uniform weights) in a city relative to the cross-section average.3 Although C2ER is a non-governmental institution, its data can be considered as “semi-official” (since they have been partly publishing in the “Statistical Abstract of the United States”). Recently, C2ER started producing COLI across counties and states of the US. In the UK, the Office for National Statistics produced relative regional consumer price levels for 2004, 2005, 2010, and 2016. The regional baskets involve the same set of goods and services as covered by the UK CPI, however, with region-specific weights used to compute Fisher-like indices for every pair of regions. These data serve for calculating final price levels in the form of the Éltető-Köves-Szulc indices with the UK as the base.4 The State Government of Western Australia produces regional price index biannually from 2011 across both regions and towns. This index is the cost of a basket containing more than 300 goods and services relative to its cost in the City of Perth with weights of the Perth CPI. Regional indices are the aggregate of town indices for a region with weights reflecting town’s share of the region’s population.5,6

The Russian Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat) provides a few indicators that represent regional price levels. Since 1992, it has been publishing monthly data on the cost of a uniform staples basket by region. The basket changed from time to time. It contained 19 foods from 1992 to 1996, 25 foods from January 1997 to June 2000, and 33 foods from July 2000 to the present. Until 2021, one more indicator, subsistence minimum, was used as a proxy of regional price levels.7 Most of 1992–2020 it was proportional to the cost of the staples basket; however, within a few years its basket included—in addition to staples—a small number of manufactured goods and services. A more representative monthly indicator was introduced in 2002, namely, the cost of a fixed basket of consumer goods and services for inter-regional comparisons of the population purchasing power. This basket (usually referred to as simply “fixed basket”) covers 83 goods and services and is also uniform across regions. At present, it is the most widespread indicator used in Russian regional studies for providing cross-regional comparability. The advantage of the basket costs is that they allow getting an idea of the absolute (and not comparative) real income. For instance, a monthly personal income per capita divided by the cost of a basket suggests how many such baskets a representative consumer can buy for his/her monthly income. At the same time, the basket costs are easily transformed into a comparative form (for example, a spatial price index can be calculated as the ratio of the basket cost in some region to the national basket cost).

Since 2009, Rosstat has started publishing annual data on COLI across a bit less than 300 cities and towns from all regions of Russia. This indicator is highly representative, including the most part of goods and services covered by the Russian CPI. Hence, it provides more accurate estimates of real regional monetary indicators than the cost of the fixed basket (not to mention the staples basket). However, the fact that the Russian COLI is reported by city/town and not by region makes it inconvenient for cross-regional comparisons. To overcome this shortcoming, the city COLI need to be aggregated into regional ones. This paper reports methodology of such aggregating and estimates regional COLI for 2016–2020. This extends results in (Gluschenko and Karandashova, 2017) that cover 2009–2015. Benefiting from the obtained COLI, real (i.e., comparable across regions) incomes per capita are estimated. As expected, adjustment for regional price differences smooths to some extent regional inequality. In addition, real incomes per capita in “macroregions,” the European and Asian parts of Russia (the latter, in turn, consisting of Siberia and the Russian Far East), are estimated over 2009–2020. A comparison evidences that the Asian part of Russia permanently remains poorer than the European part despite compensating wage differentials in the Asian part.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

From the viewpoint of the index numbers theory, two main types of methodologies of constructing spatial price indices can be distinguished. The first one bases on local baskets of goods and services with location-specific weights, so taking account of difference in consumption patterns across locations. The costs of these baskets are processed in a complex way to obtain Éltető-Köves-Szulc or Geary-Khamis spatial price indices.8 The second approach bases on a basket that is uniform across locations (so imputing the same consumption pattern to all locations). The costs of this basket in the locations relative to its cost in a benchmark location (as a rule, to the national average cost) serve as the spatial price indices. So obtained indices are less flexible than those produced by the first methodology. However, the advantage of this methodology is its significant simplicity and clarity.

The Russian COLI exploits the second methodology.9 It benefits from data collected for CPI and covers 275 goods and services (most of items included in CPI); the average national prices serve as a numeraire. Thus, an individual COLI is the price level in a given city/town relative to the average national level. Since the consumer prices are collected monthly, they are aggregated into annual values as simple arithmetic averages over 12 months. The weights in the COLI basket are the same as in the CPI for Russia as a whole. They reflect the national average consumption pattern in the previous year. COLI is estimated (and published) for all cities and towns where prices are observed.10

On average, there are 3.4 such cities/towns per region (in 2020). Most regions (67 of 85, i.e., 78%) are represented by 2 to 4 cities/towns. One city/town represents 9 regions, of which 3 are regions by themselves (federal cities Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Sevastopol11). Moscow оblast is represented by 15 cities/towns; 8 regions are represented by 5 to 7 cities/towns. The spatial sample changes from time to time, however, the changes are minor.

The source of the raw data, COLI by city/town, is Rosstat12 that indicates COLIs in integer percentages. Table 1 reports summary statistics of these data.

Table 1. .

Descriptive statistics of COLI across Russian cities/towns

| Statistic | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum, % | 70 | 70 | 73 | 73 | 74 |

| Maximum, % | 170 | 158 | 175 | 178 | 158 |

| Maximum/minimum | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| Median, % | 95.0 | 96.0 | 97.0 | 97.0 | 97.0 |

| Standard deviation, p.p. | 15.2 | 14.7 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 13.4 |

| Gini index, % | 8.0 | 7. 9 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 6.9 |

| Number of cities | 276 | 275 | 276 | 283 | 282 |

The lowest COLI were in Lagan’ (Republic of Kalmykia) in 2016, in Magas in 2017 and then in Nazran’ (Republic of Ingushetia). The table shows significant decreases in the highest COLI in 2017 and 2020. This is a result of missing COLI in the most expensive town from the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug (the most remote and expensive region of Russia) for these years in Rosstat’s 2022 report.13,14

A simple formula gives COLI for a city/town15:

|

1 |

where pirk is price for good (service) k in city/town i from region r, p0k is the national average price, wk is the weight of k-th good (service), and m is the number of items in the COLI basket.

The Russian statistics estimates regional average prices as weighted averages over cities/towns that are monitored in the region, the weights reflecting proportions of their population.16 A simple transformation of the respective formula from Rosstat17 gives the following relationship for the regional average price:

|

2 |

where Nir is the population of city/town i from region r, R(r) is the set of cities/towns in which prices are collected in region r, and nir is the weight of i-th city/town in region r.

Benefiting from Formulae (1) and (2), we can aggregate COLI across cities/towns into regional COLI in a way that is in accordance with the Russian statistical methodology:

|

3 |

As seen, it is simply a weighted average of the relevant city/town COLIs.

The source of data on population is Rosstat18 where populations are reported as of January 1. The arithmetic mean of data for two adjacent years provides the annual average populations.

As Formulae (1) and (3) show, both the city and regional COLI have a comparative form by construction. Therefore, real income estimated with the use of the regional COLI, in contrast to the cost of a basket of goods and services, only suggest how high or low is income as compared to the (nominal) national income per capita, and is silent as to actual well-being in some absolute terms.

REGIONAL COSTS OF LIVING

The Russian Federation consists of 85 federal subjects (republics, oblasts, one autonomous oblast, krais, autonomous okrugs, and three federal cities) termed federal subjects. Despite different designations, all these are equal in legal terms. In this study, a federal subject (including federal cities of Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Sevastopol) is meant by a region. There are two exceptions, though, that are due to a feature of the political division of Russia. Two federal subjects include national entities—autonomous okrugs, that are themselves the federal subjects. Namely, Arkhangelsk oblast includes the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and Tyumen oblast includes the Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets autonomous okrugs. To avoid double counting, these oblasts without autonomous okrugs are taken as regions in this study.

Table 2 tabulates regional COLIs computed by Formula (3). They are reported in integer percentages, that is, with the same precision as the raw data.

Table 2 (as well as Table 4 below) distinguishes large spatial blocks (macroregions)—European and Asian parts of Russia. The latter, in turn, is divided into Siberia and the Russian Far East. The interpretation that considers Asian Russia as consisting of Siberia and the Russian Far East exists since the 1920s. The division between macroregions is ambiguous. This study deems regions that enter the Far Eastern Federal District as of 2020 to be the Russian Far East, and those enter Siberian Federal District plus Tyumen oblast to be Siberia.

Table 4. .

Real income per capita by region (relative to the national income per capita), %

| Region | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European part of Russia | |||||

| 1. Belgorod oblast | 113 | 113 | 107 | 106 | 105 |

| 2. Bryansk oblast | 83 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 83 |

| 3. Vladimir oblast | 74 | 75 | 72 | 72 | 73 |

| 4. Voronezh oblast | 102 | 101 | 99 | 98 | 97 |

| 5. Ivanovo oblast | 78 | 80 | 74 | 75 | 75 |

| 6. Kaluga oblast | 95 | 91 | 89 | 91 | 92 |

| 7. Kostroma oblast | 82 | 82 | 78 | 80 | 75 |

| 8. Kursk oblast | 94 | 94 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| 9. Lipetsk oblast | 102 | 104 | 102 | 104 | 101 |

| 10. Moscow oblast | 124 | 123 | 123 | 123 | 120 |

| 11. Oryol oblast | 83 | 84 | 83 | 82 | 83 |

| 12. Ryazan oblast | 83 | 82 | 82 | 80 | 79 |

| 13. Smolensk oblast | 76 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 78 |

| 14. Tambov oblast | 94 | 93 | 90 | 89 | 86 |

| 15. Tver oblast | 79 | 79 | 78 | 80 | 80 |

| 16. Tula oblast | 92 | 90 | 84 | 84 | 84 |

| 17. Yaroslavl oblast | 87 | 86 | 81 | 81 | 82 |

| 18. Moscow | 158 | 162 | 164 | 165 | 167 |

| 19. Republic of Karelia | 80 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 83 |

| 20. Republic of Komi | 95 | 93 | 94 | 91 | 93 |

| 21. Arkhangelsk oblast (without autonomous okrug) | 63 | 64 | 65 | 68 | 70 |

| 22. Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 211 | 208 | 216 | 214 | 215 |

| 23. Vologda oblast | 82 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 80 |

| 24. Kaliningrad oblast | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 79 |

| 25. Leningrad oblast | 90 | 89 | 91 | 88 | 88 |

| 26. Murmansk oblast | 101 | 102 | 103 | 103 | 105 |

| 27. Novgorod oblast | 88 | 86 | 79 | 76 | 75 |

| 28. Pskov oblast | 72 | 74 | 72 | 73 | 75 |

| 29. St. Petersburg | 117 | 120 | 121 | 119 | 121 |

| 30. Republic of Adygeya | 87 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 90 |

| 31. Republic of Kalmykia | 60 | 60 | 56 | 57 | 60 |

| 32. Republic of Crimea | 60 | 63 | 65 | 63 | 65 |

| 33. Krasnodar krai | 106 | 103 | 101 | 99 | 101 |

| 34. Astrakhan oblast | 78 | 75 | 74 | 73 | 73 |

| 35. Volgograd oblast | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 76 |

| 36. Rostov oblast | 88 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| 37. Sevastopol | 89 | 87 | 86 | 82 | 80 |

| 38. Republic of Dagestan | 93 | 93 | 86 | 88 | 85 |

| 39. Republic of Ingushetia | 69 | 69 | 65 | 63 | 62 |

| 40. Kabardino-Balkarian Republic | 71 | 71 | 70 | 69 | 68 |

| 41. Karachay-Cherkess Republic | 61 | 60 | 59 | 59 | 57 |

| 42. Republic of Northern Ossetia-Alania | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 75 |

| 43. Chechen Republic | 86 | 82 | 79 | 79 | 79 |

| 44. Stavropol krai | 74 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 68 |

| 45. Republic of Bashkortostan | 98 | 95 | 92 | 91 | 89 |

| 46. Republic of Mari El | 69 | 68 | 67 | 66 | 67 |

| 47. Republic of Mordovia | 67 | 67 | 65 | 65 | 67 |

| 48. Republic of Tatarstan | 118 | 115 | 113 | 113 | 110 |

| 49. Udmurt Republic | 82 | 81 | 78 | 76 | 75 |

| 50. Chuvash Republic | 65 | 64 | 63 | 65 | 67 |

| 51. Perm krai | 91 | 91 | 88 | 88 | 84 |

| 52. Kirov oblast | 74 | 75 | 72 | 71 | 72 |

| 53. Nizhny Novgorod oblast | 98 | 95 | 93 | 96 | 93 |

| 54. Orenburg oblast | 81 | 81 | 79 | 78 | 77 |

| 55. Penza oblast | 76 | 76 | 74 | 74 | 75 |

| 56. Samara oblast | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 89 |

| 57. Saratov oblast | 73 | 72 | 74 | 74 | 76 |

| 58. Ulyanovsk oblast | 79 | 78 | 72 | 71 | 72 |

| 59. Kurgan oblast | 67 | 66 | 63 | 62 | 63 |

| 60. Sverdlovsk oblast | 111 | 109 | 110 | 111 | 106 |

| 61. Chelyabinsk oblast | 85 | 85 | 82 | 80 | 82 |

| Asian part of Russia | |||||

| Siberia | |||||

| 62. Altai Republic | 53 | 54 | 56 | 55 | 58 |

| 63. Tyva Republic | 51 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 56 |

| 64. Republic of Khakassia | 69 | 69 | 70 | 68 | 70 |

| 65. Altai krai | 78 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 72 |

| 66. Krasnoyarsk krai | 87 | 88 | 88 | 87 | 88 |

| 67. Irkutsk oblast | 75 | 78 | 77 | 78 | 79 |

| 68. Kemerovo oblast | 79 | 79 | 80 | 79 | 79 |

| 69. Novosibirsk oblast | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 89 |

| 70. Omsk oblast | 94 | 91 | 90 | 87 | 85 |

| 71. Tomsk oblast | 86 | 86 | 84 | 81 | 80 |

| 72. Tyumen oblast (without autonomous okrugs) | 92 | 92 | 93 | 92 | 91 |

| 73. Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug | 126 | 128 | 128 | 129 | 130 |

| 74. Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 186 | 189 | 192 | 197 | 212 |

| Russian Far East | |||||

| 75. Republic of Buryatia | 79 | 78 | 74 | 73 | 73 |

| 76. Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) | 99 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 99 |

| 77. Zabaykalsky krai | 71 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 73 |

| 78. Kamchatka krai | 89 | 90 | 95 | 98 | 102 |

| 79. Primorsky krai | 85 | 87 | 90 | 91 | 89 |

| 80. Khabarovsk krai | 94 | 94 | 96 | 95 | 94 |

| 81. Amur oblast | 84 | 88 | 89 | 89 | 92 |

| 82. Magadan oblast | 118 | 122 | 133 | 137 | 145 |

| 83. Sakhalin oblast | 124 | 126 | 130 | 134 | 134 |

| 84. Jewish Autonomous oblast | 67 | 67 | 67 | 68 | 69 |

| 85. Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | 139 | 145 | 145 | 143 | 157 |

Table 3 provides a generalized pattern of the regional price levels, reporting descriptive statistics of their distribution.

Table 3. .

Descriptive statistics of regional COLIs

| Statistic | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum, % | 74 | 72 | 74 | 75 | 76 |

| Maximum, % | 160 | 158 | 164 | 165 | 158 |

| Maximum/minimum | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Median, % | 97.3 | 96.3 | 97.0 | 96.8 | 96.8 |

| Standard deviation, p.p. | 16.0 | 15.9 | 15.4 | 15.1 | 14.4 |

| Gini index, % | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

The minimal COLI is peculiar to the Republic of Ingushetia in all years under consideration. The maximal COLI occurs in the Kamchatka krai (in 2016 and 2017) and the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug (in 2017 to 2020). As it is mentioned in the previous section, the most expensive town in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug is missing in 2017 and 2020. Counterfactual experiments (inserting missing COLIs with values for previous year) suggest that this leads to underestimation of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug’s COLI by 3 or 4 percent points; they would be 161% in 2017 and 162% in 2020. Similar experiments with other differences in the spatial sample across years reveal no significant effects at all. The pattern appears more or less stable with weak indications of convergence (judging from the standard deviation and Gini index).

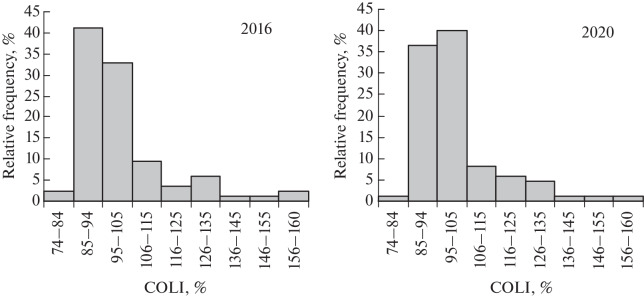

Depicting the distribution of regional COLI in the first and last years of the time span under consideration, Fig. 1 suggests that convergence does take place. The fraction of regions with price levels about the national average, 95 to 105%, increased from 33% in 2016 to 40% in 2020. However, convergence occurred mainly due to the rise in the price levels in “cheap” regions. The share of regions with COLI below 95% declined from 44 to 38%, while the group of regions with COLI above 105% shrank by one region only.

Fig. 1.

Histograms of the regional COLI in 2016 and 2020.

While Fig. 1 deals with a time dimension of the COLI distribution, Fig. 2 shows it in a spatial dimension (the range of COLI is aggregated into five grades in it). The spatial pattern of COLI looks reasonable. In the central and southern parts of European Russia, COLIs are about the national average (95 to 105% of it) or below it. Two exceptions are the country capital Moscow (128%) and the surrounding Moscow oblast (109%) as well as one more megapolis, St. Petersburg (113%). The phenomenon of high price levels in the capital and major cities is observed in many countries. Higher transportation costs are the reason for high COLI in the northern regions of European Russia. In moderately remote regions, the republics of Karelia and Komi and southern part of Arkhangelsk oblast, COLI is 108 or 109%, while in more remote Murmansk oblast, it rises to 122%, and in the difficult-to-access Nenets Autonomous Okrug it reaches 139%.

Fig. 2.

Geographical distribution of COLI in 2020. Notes: See Table 2 for regions' numbers.

In the South of Siberia, COLIs are about the national average or below it, exceeding this level only in the northern Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets autonomous okrugs. However, it seems that the Krasnoyarsk krai, with its large northern part, should have a higher COLI. The reason for the low COLI here is that this part is sparsely populated; statistical price observations cover a sole northern city, Norilsk. Despite the high price level (132%), this city contributes about 11% to the regional COLI, which gives only 3 percentage points. In the Russian Far East, COLI is about the national level in two regions only. In most regions, high COLIs are due to the remoteness of these from the rest of Russia and difficult access to some of them (because of poor transport infrastructure).

REAL INCOMES PER CAPITA IN THE REGIONS

The term “real incomes” means that they are denominated in a monetary unit with a uniform purchasing power. Its sense differs depending on whether a change in purchasing power of the monetary unit in time or across country’s locations is meant. In the former—most common—case, incomes are adjusted for inflation (typically, with the use of CPI). In the latter case, incomes are adjusted for differences in prices between locations. It is this meaning of the term “real incomes” that is used in this paper.

Table 4 reports real incomes per capita in the Russian regions relative to the national average, yrt (where t stands for years). They are computed as:

|

4 |

where Yrt is the nominal income per capita in region r, and Yt is the national income per capita. Data on nominal personal incomes per capita are drawn from EMISS19; COLIs are taken from Table 2.

The lowest real incomes in 2016–2020 were in the Tyva Republic , a depressive region in Siberia. The highest incomes featured the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, a northern oil-and-gas-extracting region (also in Siberia). In nominal terms, the lowest incomes were observed in the Tyva Republic in 2016–2019, and in the Republic of Ingushetia, a North-Caucasian region from European Russia, in 2020. The highest nominal incomes were in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug in 2016–2018, and in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug in 2019–2020.

Table 5 tabulates descriptive statistics of incomes per capita relative to the national average, comparing nominal and real incomes.

Table 5. .

Descriptive statistics of relative incomes per capita in the Russian regions

| Indicator | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal incomes | |||||

| Minimum, % | 48.5 | 47.1 | 46.9 | 47.0 | 46.8 |

| Maximum, % | 234.4 | 238.4 | 238.7 | 236.0 | 249.3 |

| Maximum/minimum | 4.8 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.3 |

| Mean, % | 91.6 | 91.4 | 91.2 | 90.8 | 91.5 |

| Median, % | 82.1 | 81.7 | 80.6 | 80.2 | 79.3 |

| Standard deviation, p.p. | 37.3 | 38.1 | 39.6 | 39.7 | 41.3 |

| Gini index, % | 18.8 | 19.0 | 19.7 | 19.9 | 20.1 |

| Real incomes | |||||

| Minimum, % | 51 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 56 |

| Maximum, % | 211 | 208 | 216 | 214 | 215 |

| Maximum/minimum | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 3.9 |

| Mean, % | 89.3 | 89.3 | 88.5 | 88.4 | 88.8 |

| Median, % | 85.1 | 85.3 | 82.2 | 81.2 | 82.2 |

| Standard deviation, p.p. | 25.2 | 25.4 | 26.7 | 27.0 | 28.2 |

| Gini index, % | 13.4 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 14.4 |

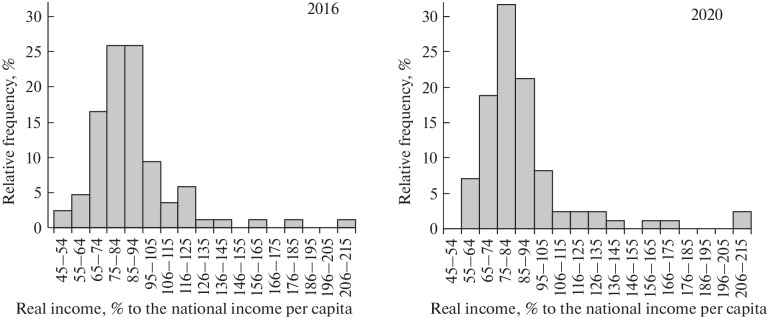

Comparison of statistics for nominal and real incomes suggests that inter-regional differences, as can be expected, are less in the case of real incomes. To some extent, they are smoothed out by the difference in regional COLI. Indeed, COLI in rich regions are on average higher than those in poor ones are. In 2020, the coefficient of correlation between nominal incomes per capita and COLI was 0.84; a 1-percent change in nominal income changed COLI by 0.32% in the same direction. This decreases regional inequality in real incomes (the Gini index) by about 30% as compared to inequality in nominal incomes. The standard deviation and Gini index evidence weak divergence of both nominal and real incomes over time. The distributions of real incomes plotted in Fig. 3 confirms this.

Fig. 3.

Histograms of the regional real incomes in 2016 and 2020.

The number of regions with real income below 95% of the national level increased in 2020 by 3 regions as compared to 2016. In general, the distribution in 2020 shifted in the direction of poorer regions. Convergence of regional COLI was not able to prevent divergence of real incomes; it only slightly decreased the divergence.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, it is interesting to compare incomes in 2020 with incomes in the pre-pandemic year. Both the descriptive statistics in Table 5 and detailed data in Table 4 indicate the absence of fundamental changes; the changes are comparable to previous years. However, as mentioned at the end of second section, they are changes in regional well-being relative to the national level and are not capable of reflecting changes in absolute well-being. To capture the latter, it is necessary to take into account the real change in the national level of personal incomes per capita,  , where CPIt – 1,t stand for annual CPI. With Y2020/Y2019 = 100.96% and inflation of 4.91% (CPI = 1.0491) we have Δ2019,2020 = 96.23%. That is, the national level of personal incomes per capita in 2020 was by 3.8% lower than in 2019 in prices of that year. It follows from Formula (4) that the change in absolute well-being in region r in 2020 as compared to 2019 can be computed as

, where CPIt – 1,t stand for annual CPI. With Y2020/Y2019 = 100.96% and inflation of 4.91% (CPI = 1.0491) we have Δ2019,2020 = 96.23%. That is, the national level of personal incomes per capita in 2020 was by 3.8% lower than in 2019 in prices of that year. It follows from Formula (4) that the change in absolute well-being in region r in 2020 as compared to 2019 can be computed as  . Real income decreased in 2020 as compared to 2019 in most regions, ranging from –8.0% (in Kostroma oblast) to –0.2%. However, slight growth occurred in nine regions. Among them are three poorest regions (the republics of Kalmykia, Altai, and Tyva) and four northern regions (Yamalo-Nenets and Chukotka autonomous okrugs, Magadan oblast, and Kamchatka krai).

. Real income decreased in 2020 as compared to 2019 in most regions, ranging from –8.0% (in Kostroma oblast) to –0.2%. However, slight growth occurred in nine regions. Among them are three poorest regions (the republics of Kalmykia, Altai, and Tyva) and four northern regions (Yamalo-Nenets and Chukotka autonomous okrugs, Magadan oblast, and Kamchatka krai).

Figure 4 relates the estimates of real incomes to geography, aggregating their range into five grades. In European Russia, poor regions prevail. As can be expected, real incomes significantly exceed the national average in the northern Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. At the same time, they are merely 105% in northern Murmansk oblast. High real incomes are peculiar to Moscow and Moscow oblast as well as to St. Petersburg despite high COLI there. Apart those, there are only two regions with real incomes above the national level, namely, the Republic of Tatarstan and Sverdlovsk oblast.

Fig. 4.

Geographical distribution of real income in 2020. Notes: See Table 4 for regions’ numbers.

The situation of Asian Russia appears negative from the socioeconomic point of view. Real incomes here should be higher than the national level in order to compensate for unfavorable natural conditions and remoteness. To this end, Russian legislation established compensating differentials for all regions of Asian Russia; increasing coefficients to wages and salaries varying from 1.15 to 2.0 (depending on the specific locality). Nonetheless, real incomes exceed the national level only in five regions of Asian Russia. Even in such northern regions as the Republic of Sakha and the Kamchatka krai, real incomes are close to the national income per capita, while the increasing coefficient is 1.4 to 2.0 in the former and 1.6 to 2.0 in the latter.

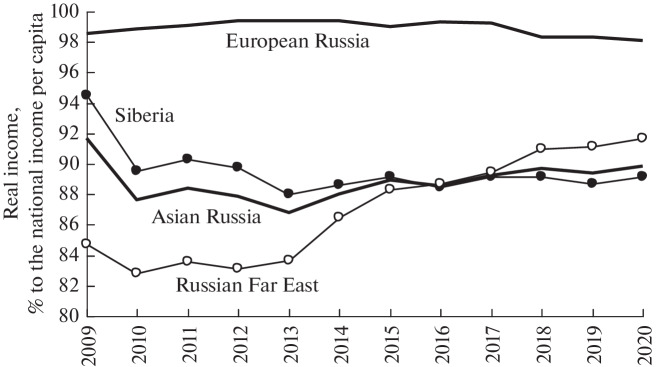

Figure 5 shows the evolution of real incomes per capita by macroregion over 2009–2020. Real incomes in macroregions are calculated as the weighted averages of regional real incomes with weights being proportions of regional population in the total population of the given macroregion. Regional real incomes for 2009–2015 are drawn from Gluschenko and Karandashova (2017).

Fig. 5.

The evolution of real personal income per capita by macroregion.

Figure 5 evidences no improvement in the situation in Asian Russia over time. Real income here is permanently lower than in the European part of the country, on average by roughly 10%.20 Some rise in real income in the Russian Far East is accompanied by its decline in Siberia. Real personal incomes, which not only do not compensate for unfavorable living conditions, but are significantly lower than in the European part of the country, are an obstacle to development of Asian Russia and contribute to its depopulation (especially in the Russian Far East).

CONCLUSION

This paper employs official statistical data on the cost-of-living indices (COLI) across Russian cities/towns over 2016–2020 to obtain regional COLI. The procedure consists in aggregating the city/town COLI by a weight-based averaging. As shown, this procedure is relatively simple, albeit cumbersome.

Regional COLIs obtained moderately converge over the time span under consideration. Their spatial distribution looks reasonable; fundamental spatial differences are explained by high costs of transportation goods to remote regions. In addition, the phenomenon observed in many other countries that the higher the incomes in a location, the higher the prices there, also takes place in Russia. The correlation coefficient between nominal personal incomes per capita in Russian regions and regional COLIs is more than 0.8; the elasticity of COLI vis-à-vis nominal income is about 0.3.

The regional COLIs are used for estimating real personal incomes per capita in the Russian regions relative to the national average. The above-mentioned phenomenon leads to decrease of regional inequality in real incomes by about 30% as compared to inequality in nominal incomes. Despite convergence of COLIs, real incomes slightly diverge over time. In the pandemic 2020, the purchasing power of income fell as compared to the previous year in 79 out of 85 regions (with the maximum decline of almost 10%).

The spatial distribution of real incomes appears unsatisfactory. The Asian part of Russia is especially at a disadvantage. Real personal incomes there not only do not compensate for unfavorable living conditions but are also significantly lower than in the European part of the country, with no signs of improvement over time.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation in the framework of large-scale research project “Socio-Economic Development of Asian Russia on the Basis of Synergy of Transport Accessibility, System Knowledge of the Natural Resource Potential, and Expanding Space of Inter-Regional Interactions,” Agreement no. 075-15-2020-804 of October 2, 2020 [grant no. 13.1902.21.0016].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Rosstat. Cost-of-Living Index across Individual Cities of the Russian Federation. 2022. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Index_stoim_jizni_2011-2021.xlsx. Accessed June 28, 2022.

This method, however, provides distorted estimates of regional price levels, especially in countries with high inflation (Gluschenko, 2006, 2016).

C2ER. Cost of Living Index Manual. Council for Community and Economic Research. Arlington, VA, 2018.

ONS. Relative regional consumer price levels of goods and services, UK: 2016. Office for National Statistics. 2018. pp. 14–16. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/articles/relativeregionalconsumerpricelevelsuk/2016/pdf. Accessed October 11, 2021.

Weinand and Auer (2020) assert, providing no reference, that also the Turkish official statistics regularly estimates regional price levels. However, I could not find respective data.

DPIRD. Regional price index 2019. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Government of Western Australia, Perth, WA. 2020. https://catalogue.data.wa.gov.au/ dataset/7ef0c9f9-6b7f-4405-af4e-19f286beba56/resource/ 720f396a-87e5-4dba-b6f1-509bc8c8098f/download/2019-rpi_web-published.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2021.

Since 2021, the subsistence minimum is determined as a proportion of the median personal income, thus losing connection with prices.

ILO. Consumer Price Index Manual: Theory and Practice. International Labor Office, Geneva, 2004. p. 500.

Rosstat. Methodological Guidelines on Calculation of Cost-of-Living Indices in Individual Cities of the Russian Federation. 2012. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/meta_ipc.doc.

As in many other countries, the Russian CPI is estimated for the urban population only.

In the article the borders of Russia are considered in accordance with the Constitution of the Russian Federation adopted by popular vote on December 12, 1993, with amendments approved during the All-Russian vote on July 1, 2020.

Rosstat. Cost-of-Living Index across Individual Cities of the Russian Federation. 2022. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Index_stoim_jizni_2011-2021.xlsx. Accessed June 28, 2022.

Rosstat. Cost-of-Living Index across Individual Cities of the Russian Federation. 2022. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Index_stoim_jizni_2011-2021.xlsx. Accessed June 28, 2022.

Table 2 and Fig. 2 in the next section give an idea of the geographical location of the mentioned regions.

Rosstat. Methodological Guidelines on Calculation of Cost-of-Living Indices in Individual Cities of the Russian Federation. 2012. p. 15. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/meta_ ipc.doc. Accessed June 28, 2022.

In fact, the weights are calculated in a more complex way, in some cases taking into account adjacent municipalities (Rosstat. Methodological Guidelines on Generating Weighting Patterns of Individual Cities for Calculation of Regional Consumer Price Indices. 2017. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/pr777-241117.pdf . Accessed June 28, 2022). The lack of relevant information forces us to use a simplified method here.

Rosstat. Official Statistical Methodology of Monitoring of Consumer Prices for Goods and Services and Calculation of the Consumer Price Indices. 2021. p. 73. https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/met_915_15122021.docx. Accessed June 28, 2022.

Rosstat. Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities. 2021. https://rosstat.gov.ru/compendium/document/ 13282. Accessed September 5, 2021.

EMISS. Monetary incomes (per capita). Integrated Interagency Informational and Statistical System of Russia (EMISS). 2021. https://fedstat.ru/indicator/30992. Accessed September 10, 2021.

It may seem strange that in both European and Asian parts of Russia real income is less than 100%. However, the weighted average of real incomes over all regions (i.e., the national real income per capita) need not be 100% (i.e., the national nominal income per capita). Consider a simple numerical example. A country consists of two regions, say, North and South, with populations 25 and 75% of the total, respectively. Let nominal income per capita be 160% of the national income per capita in the North and 80% in the South. Price level (COLI) is 130% relative to the national average in the North and 90% in the South. Then relative real income per capita is 123.1% in the North, 88.9% in the South, and 97.4% (=123.1 × 0.25 + 88.9 × 0.75) in the country as a whole.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aten B.H. Regional price parities and real regional income for the United States. Soc. Indicators Res. 2017;131:123–143. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1216-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beenstock M., Felsenstein D. Mobility and mean reversion in the dynamics of regional inequality. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2007;30:335–361. doi: 10.1177/0160017607304542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biggeri, L. and Tiziana, L., Sub-national PPPs: Methodology and application by using CPI data, Paper Prepared for the IARIW 33rd General Conference, Rotterdam, 2014. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.655.941&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- 4.Campbell, H.S., Income and cost of living: Are less equal places more costly? Social Science Quarterly, 2021. 10.1111/ssqu.13017

- 5.Gluschenko K. Biases in cross-space comparisons through cross-time price indexes: The case of Russia, BOFIT Discussion Papers, No. 9/2006. Helsinki: BOFIT; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gluschenko K. The path-dependence bias in approximating local price levels by CPIs. J. Econ. Library. 2016;3:69–76. doi: 10.1453/jel.v3i1.667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gluschenko, K.P. and Karandashova, M.A., Price levels across Russian regions, MPRA Paper No. 75041, 2017. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75041/1/MPRA_paper_75041.pdf.

- 8.Li C., Gibson J. Spatial price differences and inequality in the People’s Republic of China: Housing market evidence. Asian Dev. Rev. 2014;31:92–120. doi: 10.1162/ADEV_a_00024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinand S., Auer L.V. Anatomy of regional price differentials: Evidence from micro-price data. Spatial Econ. Anal. 2020;15:413–440. doi: 10.1080/17421772.2020.1729998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]