Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 restrictions have limited outdoor physical activities. High-intensity training (HIT) may be a valid indoor alternative. We tested whether an indoor HIT is effective in maintaining vascular function and exercise performance in runners who reduce their usual endurance training, and whether a downhill HIT is as effective as an uphill one for such purposes.

Methods

Sixteen runners performed the same 6-week HIT either uphill (UP, eight runners) or downhill (DOWN, eight runners). Eight runners continuing their usual endurance training acted as a control group (CON). The following data were collected before vs after our HIT: vascular conductance during rapid leg vasodilation to assess vasodilation capacity; V̇O2max through running incremental test to exhaustion; 2000 m running time; neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength.

Results

Both uphill and downhill HIT failed in maintaining the pre-HIT leg vasodilation capacity compared to CON, which was, however, blunted more after uphill than downhill HIT. V̇O2max and 2000 m time were similar after downhill HIT compared to CON, and augmented after uphill HIT compared to CON and DOWN. Indexes of lower-limb muscle strength were similar before vs after HIT and among groups.

Conclusion

Our HIT was ineffective in maintaining the pre-HIT leg vasodilation capacity compared to runners continuing their usual low-intensity endurance training, but did not lead to reductions in V̇O2max, 2000 m time performance, and indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength. Our data show an appealing potential for preserving exercise performance with low cardiorespiratory effort via downhill running.

Keywords: Vasodilation capacity, Vascular remodeling, Endothelial function, Endurance training

Introduction

The restrictions put in place to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus have limited or abolished outdoor physical activities. This has led to the development of new indoor exercise plans aimed at maintaining cardiovascular health and sport performance in endurance runners. High-intensity training (HIT) is a common form of training, which can be performed indoor. The use of HIT has been suggested to be effective as much as long-lasting endurance exercise in promoting cardiovascular health [1], as well as to improve athletic performance even in trained runners [2, 3]. HIT has been suggested to improve muscle power [3], running economy [2], mitochondrial content, respiratory capacity [4], and cardiorespiratory function [2, 3]. HIT close to the maximum oxygen consumption (V̇O2max) has been shown to increase V̇O2max despite a decrease in training volume [5, 6]. Two main forms of HIT are becoming increasingly popular: uphill and downhill HIT running [7, 8]. Uphill running is suggested to be effective as it leads to higher muscular activity of the lower limbs and higher cardiovascular effort compared to level-grade running at the same running speed [9]. On the other hand, downhill running leads to specific muscle strength training through eccentric exercise [8, 10] that is proposed to improve the running economy in the presence of a lower metabolic and cardiovascular demand compared to grade-level running [9–12]. Indeed, a recent study has shown that a 4-week downhill running training at an equivalent running speed to ~ 60% V̇O2max augmented the knee extension torque in both isometric and isokinetic modalities along with other neuromuscular adaptations in untrained young adults, although there was no gain in aerobic capacity [10].

Vascular conductance is a physiological parameter that expresses the ease with which blood flows through a vascular bed [13]. The precise regulation of vascular conductance is a topic of strong interest in neurovascular physiology as this mechanism is essential for the regulation and delivery of blood flow and oxygen to the various tissues of the body [13]. Chronic endurance training induces anatomical and functional arterial changes, enhancing the endothelial vasodilation function [14, 15]. Vasodilation capacity after endurance training can even exceed the ability of the heart to increase cardiac output enough to maintain blood pressure [14]. Such changes are functional to deliver a greater amount of blood flow to the working muscles during exercise [14, 15]. Additionally, the increase in endothelial vasodilation function is an important factor for health as this variable is inversely related to coronary artery disease [16]. Endurance training also improves cardiorespiratory fitness by inducing various changes at different levels in the human body, which are important not only for athletic performance, but also for cardiovascular health [17]. To date, there are no studies evaluating the effectiveness of HIT as a countermeasure to maintain vascular function and exercise performance in endurance-trained individuals forced to stop or reduce their usual endurance training, as it happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, there are no studies evaluating which one between uphill and downhill HIT could be the most effective for such purposes. We tested the hypothesis that HIT is effective in maintaining the vascular dilation capacity, an index of vascular function, and exercise performance in two similar groups of healthy recreational runners who reduced their usual endurance training compared to a control group. We also tested the hypothesis that a downhill HIT plan is as effective as an uphill one for such purposes.

Methods

Participants

Sixteen trained male runners (41.9 ± 7.6 years old) were assigned to two groups reporting similar leg vasodilation capacity and V̇O2max (details below). Runners performed the same HIT plan for 6 weeks either uphill (UP group, eight runners) or downhill (DOWN group, eight runners). Inclusion criteria were: age 18–55 years, absence of any musculoskeletal, metabolic, cardiovascular, or respiratory disease. Runners had to be regularly engaged in low-intensity running activities between 150 and 200 min weekly for at least 1 year. Exclusion criteria were a body mass index ≥ 28 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorders, and use of any drug that alters the neural cardiovascular control. Runners in UP and DOWN did not perform any high-volume running activity at low intensity during the HIT plan and stopped any individual training throughout the study. We also recruited eight other trained male runners (36.5 ± 10.1 years old; p > 0.32 compared to both UP and DOWN) who met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria but continued their usual individual endurance training to provide a control group (CON). Individuals in CON were instructed to maintain their usual low-intensity exercise training program and not to perform any high-intensity training during the 6-week protocol. Each subject in UP and DOWN reported to the lab 25 times (4 pre- and 4 post-HIT visits for vascular, exercise, and neuromuscular assessments; 17 training sessions), while subjects in CON reported to the lab 8 times (4 pre- and 4 post-HIT visits). The Internal Review Board of the Department of Neurological, Biomedical, and Movement Sciences of the University of Verona approved all procedures involving human subjects (165,038), and participants provided written, informed consent.

HIT plan

UP and DOWN performed 17 indoor HIT sessions, ran either uphill or downhill, spread across 3 times weekly and 6 weeks. Specifically, HIT sessions were performed on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, so that the recovery times between sessions were between 48 and 72 h. HIT was performed on a treadmill (Reax Run Reaxing, Milan, Italy) to control running speed and ground slope. Each session began with a 10 min warm-up and continued as indicated in Table 1. Our HIT plan was designed according to previous research suggesting V̇O2max improvements [2]. The + 11% slope for UP was chosen according to a previous study [18], while the ground slope for DOWN was arbitrarily inverted to -11% due to the relative lack of studies comparing uphill vs downhill HIT. The running speed was set at 110% of the running speed associated with V̇O2max as this intensity has been shown to induce significant increases in V̇O2max after HIT [7, 19]. The running:recovery ratio was 1:3 to allow to perform multiple sprints over the same session [7]. Specifically, the recovery was performed by walking on the treadmill at a walking speed of 4 km/h. Our training lasted 6 weeks as this HIT duration led to significant improvements in endurance parameters in previous studies [10, 20]. Runners provided their average perceived exertion through the Borg Category Ratio 0–100 (CR100) scale and average heart rate after each session.

Table 1.

The table reports the high-intensity sprints our runners performed after the 10 m warm-up period from the 1st session (S1) to the 17th session (S17) of our 6-week training plan. Treadmill inclination was set at + 11% and − 11% for UP and DOWN, respectively. The running speed was set at 110% of the running speed associated to V̇O2max. Running:recovery ratio was 1:3

| Sessions | ||

|---|---|---|

| S1: 8 × 30 s | S7: 12 × 35 s | S13: 14 × 45 s |

| S2: 8 × 35 s | S8: 12 × 40 s | S14: 16 × 40 s |

| S3: 10 × 30 s | S9: 12 × 45 s | S15: 16 × 45 s |

| S4: 8 × 40 s | S10: 8 × 30 s | S16: 8 × 30 s |

| S5: 10 × 35 s | S11: 8 × 35 s | S17: 8 × 30 s |

| S6: 10 × 40 s | S12: 10 × 30 s |

Experimental protocol

Vasodilation capacity assessment

Rapid leg vasodilation was induced by single muscle contraction [21–23]. The delta-change from baseline to peak leg vascular conductance (VC) after muscle contraction, adjusted for baseline value as covariate, was considered an index of vasodilation capacity as previously done [24, 25]. Runners were sitting on a laboratory chair with their right leg anchored at 90 degrees on immovable support [22]. Runners were suited with a beat-by-beat finger blood pressure monitoring system (Finapres Medical System BV, The Netherlands) on the third right phalanx to measure the mean arterial pressure [24, 25]. Meantime, the diameter and mean blood velocity through the right common femoral artery were continuously scanned through pulsed Doppler ultrasonography (LOGIQ S7 pro, GE, Milwaukee, USA) [24, 25]. Data were collected using a 4.4 MHz probe with a 60° angle of insonation, the ultrasound gate was adjusted to scan the whole artery width, and the sample volume was aligned and adjusted according to vessel size [24]. After approximately 15 min of rest, runners performed a maximal isometric contraction of the quadriceps for 3 s followed by relaxation [21–23, 26, 27]. Ultrasound and blood pressure data were collected at baseline and for 60 s after muscle relaxation [22, 24, 25]. The vasodilation capacity assessment was performed before and within 1 week after the HIT plan conclusion.

Exercise performance assessment

V̇O2max was measured through a running maximal incremental test up to voluntary exhaustion on the treadmill (+ 0.5 km/h/min; + 1% ground slope; starting speed 8 km/h). This evaluation also allowed to calculate the 110% of the running speed associated with V̇O2max to be used in the HIT. Furthermore, runners were asked to give a maximal effort to achieve the best performance in a 2000 m track and field individual time trial. Runners repeated the V̇O2max assessment and 2 000 m running test before and within 1 week after the HIT plan conclusion.

Neuromuscular assessment

The vertical jump height performed through counter movement jump test was assessed by Optojump Next (Microgate, Italy) in UP, DOWN, and CON [28]. The one-repetition maximum (1-RM) at the leg press (Technogym, Italy) was estimated using the methodology developed by Brzycki [29] after performing several (eight to ten) repetitions to fatigue in UP, DOWN, and CON. This test estimates the maximal weight an individual can lift for only one repetition [29]. Subjects were trained in the correct technique before assessment. Additionally, in UP and DOWN, the maximal voluntary contraction force of the lower limbs evaluated through a 5 s isometric Mid-Thigh Pull Test [30] was measured using a strain-gauge transducer (Deltatech, Italy) and PowerLab (ADInstruments, USA) as previously done [31].

Data treatment

Ultrasound data were used to calculate the leg blood flow (ml*min−1) as mean blood velocity (cm*s−1)*π*common femoral artery radius (cm)2*60 as previously shown [16, 24]. Leg blood flow and mean arterial pressure data were exported and calculated second-by-second with a 3-s rolling average [16, 24]. Leg VC was calculated second-by-second as blood flow divided by mean arterial pressure [16, 24]. The baseline and peak VC reached after (< 10 s) muscle contraction were determined. Change scores in VC (peak VC minus baseline VC) were calculated on the data collected before and after HIT. The maximal voluntary contraction force during the Mid-Thigh Pull Test was reported as the highest force attained during the 5 s pull.

Statistical analysis

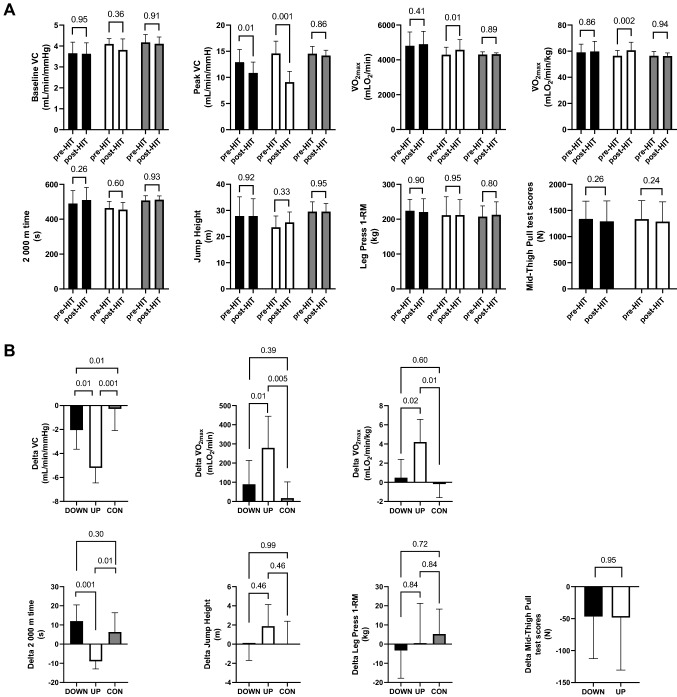

The normality and homogeneity of the data distribution were tested through Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. As the data were normally distributed, baseline VC, peak VC, V̇O2max, 2000 m times, and neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength were compared through two-way repeated measure ANOVA with Sidak post hoc test comparing UP vs DOWN vs CON, before vs after HIT (Fig. 1A). The difference between post- and pre-HIT VC change scores, V̇O2max, 2000 m times, vertical jump height, and estimated 1-RM at the leg press were compared among the three groups via one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using baseline values as covariates (Fig. 1B). The difference between post- and pre-HIT Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull Test scores were compared in UP vs DOWN unpaired via t test. The mean and SD values of differences in VC change scores, V̇O2max, and 2000 m times between post- and pre-HIT conditions were used to determine the effect sizes. Statistical power was tested a posteriori via software (GPower 3.1.9.7; Universität Düsseldorf, Germany) by setting an F test (ANCOVA), effect sizes, and level of significance α = 0.05, to ensure that changes in those variables reached a statistical power greater than 80%. Changes in neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength have a secondary role within our study. GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, United States) and MATLAB (MathWorks, USA) were used for statistical analysis and graphs.

Fig. 1.

A Baseline VC, peak VC, V̇O2max before and after normalization to body mass, 2000 m time, jump height, leg press 1-RM, and Mid-Thigh Pull Test scores before versus after the 6-week HIT plan in DOWN (black bars), UP (white bars), and CON (grey bars). B Difference between post- and pre-HIT values of VC change scores, V̇O2max, and 2000 m time, jump height, leg press 1-RM, and Mid-Thigh Pull Test scores among DOWN (black bars), UP (white bars), and CON (grey bars), adjusted for differences in baseline values. Numerical p values are reported

Results

Both UP and DOWN decreased (p < 0.001) their pre-HIT training volume by about threefold during our HIT plan (from: UP 43.5 ± 12.4, DOWN 47.1 ± 8.1; to 13.5 ± 0.5 km/week), while CON did not change (p = 0.82) its training volume (from 40.1 ± 16.4 to 42.1 ± 15.1 km/week). Averaged BORG CR100 values were much higher during uphill than downhill HIT (UP: 86.08 ± 17.41 AU or 'very to extremely strong' vs DOWN: 20.09 ± 5.87 AU or 'weak to moderate’, p < 0.00001). Averaged BORG CR100 values in CON (49.0 ± 9.6 AU or 'strong') were lower compared to UP (p < 0.001) but higher compared to DOWN (p < 0.001). The running speeds were similar in UP vs DOWN (UP: 18.7 ± 2.3 km/h vs DOWN: 19.0 ± 2.0 km/h, p = 0.79) but lower in CON compared to both UP and DOWN (CON: 12.5 ± 1.1 km/h, both p < 0.001). The average heart rates during the whole sessions were higher in UP vs DOWN (UP: 168.6 ± 7.4 bpm vs DOWN: 148.7 ± 9.5 bpm, p < 0.001). The averaged heart rates in CON (158.6 ± 5.4 AU or 'strong') were lower compared to UP (p < 0.001) but higher compared to DOWN (p < 0.001). The body weight was similar among groups before starting the HIT training (UP: 76.1 ± 5.4 kg; DOWN: 81.1 ± 9.3 kg; CON: 76.4 ± 4.3 kg; comparison among groups all p > 0.59). The change in body weight after the 6-week protocol was similar among groups (UP: − 0.3 ± 1.2 kg; DOWN: 0.1 ± 0.95 kg; CON: 0.15 ± 0.75 kg; comparison among groups all p > 0.83).

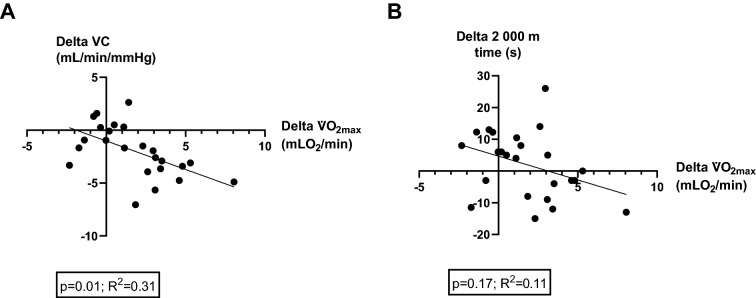

As reported in Fig. 1A, before starting the training plan, the three groups reported similar values of VC at baseline and after the leg muscle contraction. Pre-HIT V̇O2max, 2000 m time values were also similar among groups. As shown in Fig. 1B, after statistically accounting for baseline VC as a covariate, leg vasodilation capacity in response to muscle contraction was blunted in all groups after the 6-week HIT, but to a greater extent in the groups performing HIT vs CON and in UP vs DOWN. V̇O2max was maintained post- vs pre-HIT in DOWN and CON and augmented in UP (Fig. 1A) both before and after normalizing to body weight. The change in V̇O2max was greater in UP vs CON and UP vs DOWN both before and after normalizing to body weight. The 2000 m time performance was maintained post- vs pre-HIT in all groups, although UP led to better results compared to DOWN and CON. As shown in Fig. 2, there was a significant but poor relationship between the changes in V̇O2max and VC change scores, while there was no relationship with 2000 m time performance. The vertical jump height and estimated 1-RM scores were similar among groups both before vs after HIT, and did not change after the training period within each group. Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull Test scores were similar pre- vs post-HIT in both UP and DOWN and did not change after the training period within each group.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the changes in V̇O2max and VC change scores (A), and between changes in V̇O2max and 2000 m time performance (B)

Discussion

We assessed the outcome of an indoor HIT plan, ran either uphill or downhill, in maintaining vasodilation capacity and exercise performance in two groups of similar healthy recreational runners who reduced their usual endurance training compared to a control group. The key findings were that, regardless of the ground slope, our HIT plan was not effective in maintaining the pre-HIT leg vasodilation capacity compared to control individuals who continued their usual low-intensity endurance training. Moreover, vasodilation capacity diminished to a greater extent in UP compared to DOWN. However, our HIT plan was effective in maintaining or improving V̇O2max and 2 000 m time performance compared to CON, in which the uphill HIT overall resulted to be more effective. No changes in neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength were found among groups, regardless of the training modality and ground slope.

Endurance exercise training chronically induces anatomical and functional physiological adaptations aimed at improving exercise capacity and performance [14, 15, 17]. The different frequencies, volumes, and intensities of training have been shown to affect the extent of vascular adaptations and functions [14, 15]. In this study, the lower-limb vasodilation capacity was assessed through a single muscle contraction task of the quadriceps [21–23, 26, 27]. This technique leads to sudden leg vasodilation, which takes place within a few seconds after muscle relaxation and comes back toward baseline values within 20–30 s [21–23, 26, 27]. Previous studies have shown that rapid vasodilation following a single muscle contraction is due to the release of local vasodilator agents produced by the vascular endothelium or muscle itself that quickly relaxes vascular smooth muscle [21, 24, 27, 32]. Vasodilation capacity is an index of vascular function and is essential to ensure adequate delivery of blood and oxygen to organs and tissues [13, 16]. Improvements in vasodilation capacity have been associated with improved vascular health and with the positive effects of regular exercise [13, 16]. However, the positive effects of exercise on vascular function are reversible and physical deconditioning in endurance-trained individuals has been shown to induce a rapid and dose-dependent inward artery remodeling, wall thickening, and upregulation of vasoconstrictor mechanisms that overcomes downregulation of vasodilator effects [33]. Such changes are consistent with a reduction in vasodilation capacity. Thus, the training volume reduction during HIT might represent a potential factor leading to a relative physical deconditioning compared to pre-HIT levels and explain the failure to maintain vasodilation capacity in both UP and DOWN compared to CON. Interestingly, the vasodilation capacity diminished to a greater extent in UP compared to DOWN (Fig. 1B), although the cardiovascular effort was greater in UP according to the Borg scale and heart rate scores, and the training volumes and speeds were similar. Our data might point out a negative effect of very high exercise intensities on vasodilation capacity. Indeed, there was a significant relationship between changes in V̇O2max (which augmented in UP only) and VC change scores, but just 31% of the variability observed in the target variable was explained by the regression model (Fig. 2A). In this regard, strong exercise intensities seem to contribute to endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation due to the large production of ROS, which overcomes nitric oxide production and results in an altered vascular environment that promotes an oxidative status [34, 35]. Thus, the “very to extremely strong” exercise intensity in UP might be a possible explanation for the greater reduction in vasodilation capacity, although further studies are needed to confirm such a hypothesis and elucidate the precise mechanisms.

Our HIT plan was effective to counteract the threefold training volume reduction to preserve runners’ V̇O2max and 2000 m time performance compared to CON (Fig. 1B). In this regard, downhill HIT proved to be an effective countermeasure to maintain V̇O2max and 2 000 m time performance compared to CON, while uphill HIT even improved both functional parameters compared to both DOWN and CON. The greater cardiorespiratory improvements in UP are consistent with the greater exercise intensity while running uphill at the same running speed than in DOWN and with the major impact on the central and peripheral components affecting V̇O2max [4, 36]. On the other hand, downhill HIT has been suggested to provide minor effects on the V̇O2max [10], but to improve the lower-limb muscle strength [10], which is an important factor related to running economy [11, 12]. Indeed, V̇O2max changes alone do not explain the 2000 m time performance changes (Fig. 2B). Thus, the mechanisms for preserving V̇O2max and 2000 m time performances are likely to differ between UP and DOWN. Lower-limb muscle strength is a determinant factor of downhill running performance [37]. The analysis of vertical jump height and 1-RM at the leg press are widely used methods for evaluating the muscle strength expressed by the lower limbs [28, 29]. Interestingly, no changes in both parameters were found among the three groups after the 6-week training period. Moreover, there were no changes in Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull Test scores pre- vs post-HIT in both UP and DOWN. Our data contrast with previous findings suggesting improvements in lower-limb muscle strength after a short downhill running training at low intensity [10]. Indeed, Bontemps et al. [10] reported that eccentric muscle strength augmented already after 2 weeks of downhill running training at an equivalent running speed to about 60% V̇O2max, while knee extension torque in both isometric and isokinetic modalities augmented after 4 weeks of training. The discrepancy between the results of Bontemps et al. [10] and ours might be explained by the different initial training status of the subjects (untrained adults vs trained adult runners, respectively). However, regardless of the ground slope, our HIT plan was also effective to maintain neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength compared to CON despite the threefold training volume reduction.

Limitations

Single muscle contraction-induced vasodilation [21–23, 26, 27] is not a gold-standard measure of vascular or endothelial function. However, this measure along with the focus on VC allows to evaluate changes in the global vasodilation capacity of the leg [16, 38], which is predominantly nitric oxide dependent and includes changes at the microvascular level [21, 24, 27, 32, 38]. Changes in VC responses to mechanical stimuli are of particular interest for vascular physiology as this variable is involved in the precise regulation of muscle blood flow along with the mean arterial pressure [13]. Moreover, we have previously shown that information provided by rapid vasodilation is similar to that provided by gold-standard techniques [16]. Further studies can assess differences in variables of more clinical interest, such as artery flow-mediated dilation, although the analysis of a single arterial segment provides a measurement of conduit function, which is a local outcome that may be independent of the entire leg vasodilation [39]. Although the sample size was relatively small, the statistical power was greater than 80% in the changes of all variables. This is likely due to the massive differences in the exercise type and intensity among CON, UP, and DOWN. The 1-RM score at the leg press was estimated after performing several repetitions to fatigue through the methodology developed by Brzycki [29]. This test has limitations in comparing the muscle strength of one group of individuals to another, but its use is fair to compare an individual's performance to their previous performance [29]. Furthermore, the use of indirect indexes to evaluate changes in lower extremity muscle strength among groups provides only exploratory information.

Health implications

HIT is often proposed as a non-pharmacological strategy to improve cardiovascular health [40]. The failure of HIT to maintain vasodilation capacity does not suggest this as an effective countermeasure to maintain vasodilation capacity. Furthermore, the greater blunting of vasodilation capacity in UP compared to DOWN may question the effectiveness of very high exercise intensities in promoting or preserving vascular health. Although downhill HIT did not improve V̇O2max and 2000 m time performance as in contrast uphill HIT did, downhill HIT proved to be an effective countermeasure to maintain V̇O2max, 2000 m time performance, and neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength with a lower cardiorespiratory effort. These findings might lead to translational studies aimed at proposing new strategies or training plans to preserve cardiorespiratory fitness or exercise capacity with low cardiovascular effort, which may be particularly helpful in individuals with low cardiovascular exertion tolerance.

Future research

Future investigations should assess the changes in a wider array of indicators of cardiovascular health and neuromuscular fatigue after uphill and downhill training, as well as the relationship between exercise intensity and vascular function in health and disease. Moreover, the effectiveness of downhill training in a clinical environment to maintain cardiorespiratory fitness and exercise capacity with low cardiovascular effort in sensible populations should be tested.

Conclusion

Our HIT plan proved to be ineffective in maintaining the pre-HIT leg vasodilation capacity compared to control individuals who continued their usual low-intensity endurance training, but did not lead to reductions in V̇O2max, 2000 m time performance, and neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength. Our data might reveal a negative effect of very high exercise intensities on vascular function as individuals in UP reported a greater blunting of leg vasodilation capacity compared to those in DOWN. Downhill HIT appears to be an appealing countermeasure for maintaining V̇O2max, 2000 m time performance, and neuromuscular indexes related to lower-limb muscle strength in runners who reduce their regular endurance training volume with a significantly lower cardiovascular effort.

Author contributions

Author contributions: study concept and design (AG, LB, CT); training and athletes management (LB, CT); vascular measures (AG); exercise testing (LB, CT); data analysis (AG); original draft preparation (AG); review and critical revision of the manuscript (AG; LB; AC; FS; CT); all authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval and Informed consent

The Internal Review Board of the Department of Neurological, Biomedical, and Movement Sciences of the University of Verona approved all procedures involving human subjects (165038), and participants provided written, informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gibala MJ, Little JP, MacDonald MJ, Hawley JA. Physiological adaptations to low-volume, high-intensity interval training in health and disease. J Physiol. 2012;590:1077–1084. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García-Pinillos F, Soto-Hermoso VM, Latorre-Román PA. How does high-intensity intermittent training affect recreational endurance runners? Acute and chronic adaptations: a systematic review. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molinari T, Molinari T, Rabello R, Rodrigues R. Effects of 8 weeks of high-intensity interval training or resistance training on muscle strength, muscle power and cardiorespiratory responses in trained young men. Sport Sci Health. 2022;18:887–896. doi: 10.1007/s11332-021-00872-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs RA, Flück D, Bonne TC, et al. Improvements in exercise performance with high-intensity interval training coincide with an increase in skeletal muscle mitochondrial content and function. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115:785–793. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00445.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibala MJ, Little JP, van Essen M, et al. Short-term sprint interval versus traditional endurance training: similar initial adaptations in human skeletal muscle and exercise performance. J Physiol. 2006;575:901–911. doi: 10.1113/JPHYSIOL.2006.112094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacInnis MJ, Gibala MJ. Physiological adaptations to interval training and the role of exercise intensity. J Physiol. 2017;595:2915–2930. doi: 10.1113/JP273196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes KR, Hopkins WG, McGuigan MR, Kilding AE. Effects of different uphill interval-training programs on running economy and performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2013;8:639–647. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.8.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toyomura J, Mori H, Tayashiki K, et al. Efficacy of downhill running training for improving muscular and aerobic performances. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43:403–410. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemire M, Lonsdorfer-Wolf E, Isner-Horobeti M-E, et al. Cardiorespiratory responses to downhill versus uphill running in endurance athletes. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2018;89:511–517. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2018.1510172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bontemps B, Gruet M, Louis J, et al. The time course of different neuromuscular adaptations to short-term downhill running training and their specific relationships with strength gains. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022;122:1071–1084. doi: 10.1007/S00421-022-04898-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li F, Newton RU, Shi Y, et al. Correlation of eccentric strength, reactive strength, and leg stiffness with running economy in well-trained distance runners. J Strength Cond Res. 2021;35:1491–1499. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen TC, Nosaka K, Tu JH. Changes in running economy following downhill running. J Sports Sci. 2007;25:55–63. doi: 10.1080/02640410600718228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckwalter JB, Clifford PS. The paradox of sympathetic vasoconstriction in exercising skeletal muscle. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2001;29:159–163. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green DJ, Spence A, Rowley N, et al. Vascular adaptation in athletes: Is there an “athlete’s artery”? Exp Physiol. 2012;97:295–304. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green DJ, Hopman MTE, Padilla J, et al. Vascular adaptation to exercise in humans: role of hemodynamic stimuli. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:495–528. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gentilin A, Moghetti P, Cevese A, et al. Sympathetic-mediated blunting of forearm vasodilation is similar between young men and women. Biol Sex Differ. 2022;13:33. doi: 10.1186/S13293-022-00444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin X, Zhang X, Guo J, et al. Effects of exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavaliauskas M, Jakeman J, Babraj J. Early adaptations to a two-week uphill run sprint interval training and cycle sprint interval training. Sports. 2018;6:72. doi: 10.3390/sports6030072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: Part II: anaerobic energy, neuromuscular load and practical applications. Sports Med. 2013;43:927–954. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milanović Z, Sporiš G, Weston M. Effectiveness of high-intensity interval training (HIT) and continuous endurance training for VO2max improvements: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Sports Med. 2015;45:1469–1481. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tschakovsky ME, Shoemaker JK, Hughson RL. Vasodilation and muscle pump contribution to immediate exercise hyperemia. Am J Physiol. 1996 doi: 10.1152/AJPHEART.1996.271.4.H1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osada T, Mortensen SP, Rådegran G. Mechanical compression during repeated sustained isometric muscle contractions and hyperemic recovery in healthy young males. J Physiol Anthropol. 2015 doi: 10.1186/S40101-015-0075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Credeur DP, Holwerda SW, Restaino RM, et al. Characterizing rapid-onset vasodilation to single muscle contractions in the human leg. J Appl Physiol. 2015;118:455–464. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00785.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentilin A, Tarperi C, Skroce K, et al. Effect of acute sympathetic activation on leg vasodilation before and after endurance exercise. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2021;57:53–67. doi: 10.1540/JSMR.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gentilin A, Tarperi C, Skroce K, et al. Effects of acute sympathetic activation on the central artery stiffness after strenuous endurance exercise. Sport Sci Health. 2022;1:1–9. doi: 10.1007/S11332-022-00941-0/FIGURES/2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong K-S, Kim K (2017) Skeletal muscle contraction-induced vasodilation in the microcirculation. J Exerc Rehabil 13:502–507. 10.12965/jer.1735114.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Clifford PS, Hellsten Y. Vasodilatory mechanisms in contracting skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:393–403. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00179.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahar MT, Welk GJ, Janz KF, et al. Estimation of lower body muscle power from vertical jump in youth. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2022;26:324–334. doi: 10.1080/1091367X.2022.2041420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brzycki M. Strength testing—predicting a one-rep max from reps-to-fatigue. J Phys Educ Recreat. 2013;64:88–90. doi: 10.1080/07303084.1993.10606684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grgic J, Scapec B, Mikulic P, Pedisic Z. Test-retest reliability of isometric mid-thigh pull maximum strength assessment: a systematic review. Biol Sport. 2022;39:407. doi: 10.5114/BIOLSPORT.2022.106149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keogh C, Collins DJ, Warrington G, Comyns T. Intra-trial reliability and usefulness of isometric mid-thigh pull testing on portable force plates. J Hum Kinet. 2020;71:33. doi: 10.2478/HUKIN-2019-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong KS, Kim K (2017) Skeletal muscle contraction-induced vasodilation in the microcirculation. J Exerc Rehabil 13:502–507. 10.12965/jer.1735114.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Thijssen DHJ, Green DJ, Hopman MTE. Blood vessel remodeling and physical inactivity in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:1836–1845. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00394.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durand MJ, Gutterman DD. Exercise and vascular function: How much is too much? Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;92:551–557. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergholm R, Mäkimattila S, Valkonen M, et al. Intense physical training decreases circulating antioxidants and endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 1999;145:341–349. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Astorino TA, Allen RP, Roberson DW, Jurancich M. Effect of high-intensity interval training on cardiovascular function, V̇O 2max, and muscular force. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26:138–145. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318218dd77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemire M, Hureau TJ, Favret F, et al. Physiological factors determining downhill vs uphill running endurance performance. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24:85–91. doi: 10.1016/J.JSAMS.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ichinose M, Nakabayashi M, Ono Y. Rapid vasodilation within contracted skeletal muscle in humans: new insight from concurrent use of diffuse correlation spectroscopy and Doppler ultrasound. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320:H654–H667. doi: 10.1152/AJPHEART.00761.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossman MJ, Groot HJ, Garten RS, et al. Vascular function assessed by passive leg movement and flow-mediated dilation: initial evidence of construct validity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H1277–H1286. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00421.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kramps K, Lane-Cordova A. High-intensity interval training in cardiac rehabilitation. Sport Sci Health. 2021;17:269–278. doi: 10.1007/s11332-021-00731-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.