Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies to the encapsulated fungus Cryptococcus neoformans produce different immunofluorescence (IF) patterns after binding to the polysaccharide capsule. To explore the relationship between the IF pattern and the location of antibody binding, two immunoglobulin M (IgM) monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (12A1 and 13F1) that differ in protective efficacy and IF pattern and one protective IgG1 MAb (2H1) were studied by IF and electron microscopy (EM). Fixing C. neoformans cells in lung tissue for EM resulted in significantly better preservation of the capsule than fixing yeast cells in suspension. The localization of MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 by immunogold EM differed depending on whether the MAb was bound to cells in cut tissue sections embedded in plastic or to cells in solution. In cut tissue sections, MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 bound throughout the capsule, whereas in solution both MAbs bound near the capsule surface. To investigate whether antibody binding to the C. neoformans capsule affected the binding of other primary or secondary reagents, various combinations of MAbs 12A1, 13F1, and 2H1 were studied by direct and indirect IF. The IF pattern and location of binding for MAbs 12A1, 13F1, and 2H1 varied depending on the presence of other capsule-binding MAbs and the method of detection. The results show that (i) binding of MAbs to the C. neoformans polysaccharide capsule can modify the binding of subsequent primary or secondary antibodies; (ii) the IgM MAbs bind primarily to the outer capsule regions despite the occurrence of their epitopes throughout the capsule; and (iii) MAb 2H1 staining of newly formed buds is reduced, suggesting quantitative or qualitative differences in bud capsule.

Polysaccharide capsules are associated with virulence for many pathogens. Studies in the early 20th century found that antibody binding to bacterial polysaccharide capsules promotes phagocytosis, complement activation, agglutination, and capsular reactions (reviewed in reference 2). Although much is known about the interaction of antibody molecules with polysaccharide antigens in the fluid phase, relatively little information is available regarding antibody binding to intact microbial capsules. Cryptococcus neoformans is remarkable among the medically important fungi because it has a large polysaccharide capsule that is composed primarily of glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) (6). Dozens of well-characterized monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that bind to the GXM component of the cryptococcal capsule are available (3, 11, 12, 27, 34). The combination of a large polysaccharide capsule and the availability of MAb reagents makes this fungus a particularly powerful system to study antibody-capsule interactions. Like the case for other encapsulated pathogens, the complement system and humoral immunity contribute to protection against C. neoformans infection (reviewed in references 15, 18, 26, and 38).

The protective efficacy of antibodies against C. neoformans depends on the antibody specificity and isotype (reviewed in references 15, 26, and 38). MAbs to C. neoformans can mediate many biological functions, including protection in mice (reviewed in reference 38), opsonization (24, 32), complement activation (19), and lymphocyte proliferation and modification of cytokine release by mononuclear cells (33, 39). The immunoglobulin M (IgM) MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 differ in epitope specificity and protective efficacy (23). These two IgM MAbs are believed to originate from a single pre-B cell, but their variable regions differ by several amino acid substitutions as a result of somatic mutations (23). MAb 12A1 is protective and binds to serotype A, D, and AD strains in an annular indirect immunofluorescence (IF) pattern (7, 8). In contrast, MAb 13F1 binds to A and D strains in annular and punctate patterns, respectively (7, 8). Annular IF patterns have been correlated with the ability of the MAb to mediate protection for a small number of C. neoformans strains (25). Punctate binding by MAb 13F1 has not been associated with protective efficacy (23, 25). In vitro assays have shown that punctate binding is associated with poor opsonic activity, whereas annular binding is associated with opsonization and killing of C. neoformans by murine macrophages (8). However, the nature of the antigen-antibody interactions responsible for the annular and punctate binding patterns by IF is not understood.

To understand the function of antibodies against encapsulated pathogens, it is important to determine how they interact with microbial capsules. However, a persistent problem in this field is that microbial capsules are fragile and easily disrupted by sample preparation for ultrastructural studies. In this study, we explored the binding of MAbs to the C. neoformans capsular polysaccharide using electron microscopy (EM) and IF. EM studies took advantage of the serendipitous observation that C. neoformans capsules are well preserved when the fungus is studied after instillation into mouse lung tissue. The results indicate that different binding patterns reflect differences in the location of antibody binding to the polysaccharide capsule and that the binding of one antibody to the capsule can modify the binding of subsequent antibodies.

(The data in this paper are from a thesis to be submitted by J.R. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. from the Sue Golding Graduate Division of Medical Science, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Bronx, N.Y.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. neoformans.

American Type Culture Collection strain 24067 (serotype D) was used for all experiments. This strain was selected for study because it produces annular and punctate IF patterns after MAb 12A1 and 13F1 binding, respectively (23). Serotype D strains are common among clinical isolates in Europe (10). C. neoformans cells were grown in Sabouraud dextrose broth for 24 to 48 h at 30°C, collected by centrifugation, washed with 0.02 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, and used in antibody binding experiments. The average capsule size of strain 24067 is 2.8 ± 1.4 μm in vitro or 20.0 ± 6.1 μm in vivo (29).

MAbs.

The MAbs 13F1 (IgM), 12A1 (IgM), and 2H1 (IgG1) have been described elsewhere (4, 22, 23). MAb 2H1 has serological characteristics similar to those of MAb 12A1 and probably binds to the same antigenic determinant (23). Hybridoma supernatant fluids were concentrated to yield solutions with high MAb concentration. Ascites fluid obtained from BALB/c mice injected with hybridoma cells was also used as a source of hybridoma protein. MAb 2H1 (IgG1) was purified from ascites fluid using protein G affinity chromatography (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) as instructed by the manufacturer. MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 (IgM) were purified from ascites fluid using immobilized mannan-binding protein (Pierce) as instructed by the manufacturer. The concentration of MAb was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay relative to isotype-matched standards of known concentration. Purified MAb 2H1 was labeled with Alexa 546, and MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 were labeled with Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), as instructed by the manufacturer. Alexa 546 is similar to rhodamine and has absorption and fluorescence emission maxima of ∼558 and 573 nm, respectively. Alexa 488 is similar to fluorescein and has absorption and fluorescence emission maxima of ∼494 and 519 nm, respectively.

Mice.

A/JCr mice were used for infection experiments to investigate the expression of the 12A1 and 13F1 epitopes in vivo. That mouse strain was used because it is very susceptible to infection (28) and the higher tissue burdens facilitated identification of yeast cells in organ homogenates. C57BL/6 mice were used for all experiments where C. neoformans was inoculated intratracheally to preserve the capsule for EM. Mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, Md.) and infected intratracheally as described elsewhere (14). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 65 mg of sodium pentobarbital per kg of body weight and inoculated with 106 C. neoformans cells into the trachea following exposure via a midline neck incision using a 26-gauge needle attached to a tuberculin syringe. At either 5 min, 2 h, or 14 days after infection, mice were killed by cervical dislocation and the lungs were removed.

Immunogold labeling.

The lungs were fixed overnight in Trump's EM fixative (1% glutaraldehyde–4% paraformaldehyde in PBS), incubated in 1% osmium for 1 h, dehydrated, and embedded in araldite-Epon. Ultrathin sections were placed on copper or nickel grids and imaged using a JEOL 100CX electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The same protocol was used for experiments to study epitope distribution in yeast cells during infection, except that lungs were removed at day 14 of infection. For labeling of tissue postfixation, tissue on nickel grids from infected mice was incubated in 3% H2O2 for 10 min, washed in PBS, and etched for 10 min in a saturated solution of sodium periodate. Etching was done only for sections stained postembedding, and this step did not destroy the GXM, as evidenced by strong immunogold labeling in etched samples with the three MAbs. Sections were blocked by incubation in 2% goat serum and incubated in MAb 12A1, 13F1, or 2H1 or in murine IgM or IgG as a control at a concentration of 5 μg/ml overnight at 4°C. The murine antibody controls had no reactivity for the yeast or the surrounding murine lung tissue. After washing, sections were incubated in biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (GAM-IgM) (for 12A1 or 13F1) or GAM-IgG (for 2H1) (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, Ala.) (each at 5 μg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and incubated in streptavidin conjugated to 10-nm gold (Goldmark Biologicals, Philipsburg, Pa.) at a dilution of 1:30 for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the grids were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde.

For labeling of C. neoformans cells prior to inoculation into mice, 2 × 108 washed yeast cells were incubated in either 12A1, 13F1, or murine IgM (10 μg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature and washed. Additional samples were also incubated for 2 h at room temperature in GAM-IgG or GAM-IgM conjugated to 10-nm gold diluted 1:30. One mouse each was inoculated with one of these six samples. In an additional experiment, immunogold labeling was performed as above, except that the primary antibodies were used at a concentration of 200 μg/ml. Grids from this latter experiment were also incubated after embedding with gold-conjugated secondary antibody.

IF of yeast cells from organ homogenates.

Brain and lung tissue were ground by mechanical disruption through a mesh strainer in 10 ml of PBS. Aliquots of the organ homogenate were washed twice with PBS. MAb 12A1 or 13F1 was added to the homogenate at a concentration of 50 μg/ml in blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin, 0.5% horse serum) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were then washed twice with blocking solution, incubated with 10 μg of fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC)-labeled GAM-IgM (Southern Biotechnology) per ml for 30 min at 37°C in the dark, washed again with blocking solution, and suspended in mounting medium (0.1 M n-propyl gallate in PBS [Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.]). Twenty microliters of cell suspension was placed on a slide with 20 μl of 1% diethanol–PBS (Ciba-Geigy, Greensboro, N.C.), which stains the fungal cell wall (20). Coverslips were mounted, and a small drop of India ink (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was added. The slides were then viewed with an Olympus IX 70 microscope (Olympus America, Melville, N.Y.) with 60× numerical aperture 1.4 optics equipped with standard FITC and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) filters. Image reconstruction was done using Adobe Photoshop version 3 as described below.

In vitro IF studies.

Slides were coated with poly-l-lysine (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma), and 106 yeast cells were allowed to air dry on slides so that organisms adhered. Previous studies have shown that the IF patterns produced by MAb binding to C. neoformans are the same regardless of whether the antibody is bound to yeast cells in solution or after attachment to glass slides (8, 25). MAb 2H1, 12A1, or 13F1 was added at a concentration of 200 μg/ml in blocking solution. FITC-labeled GAM-IgM (F-GAM-IgM), F-GAM-IgG1, tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled GAM-IgM (R-GAM-IgM), and R-GAM-IgG1 (all from Southern Biotechnology) were added at a concentration of 10 μg/ml after application of each unconjugated MAb. The binding pattern of each of the three MAbs was studied (i) individually using primary unconjugated MAbs followed by FITC- or TRITC-labeled GAM reagents, (ii) with the directly labeled MAbs, or (iii) in various combinations as listed in Table 1. All incubations were done at 37°C for 30 min, and slides were washed three times with PBS between application of reagents. Slides were washed again with PBS, 30 μl of mounting medium (0.1 M n-propyl gallate–50% glycerol in PBS) was added, and coverslips were placed. The slides were then viewed as described above. Fluorescent images were recorded with narrow band filter sets to ensure that there was no cross talk or spillover from one filter set to the others. Grey scale images were merged. This method is equivalent to multiple exposure photography but with the benefits of wider linear response and wider dynamic range, guaranteed optical separation of filters, and the convenience of digital storage. Spatial registration of images with different filter sets was calibrated with 0.2-μm-diameter beads as part of the standard quality control at the microscope facility. Images were recorded in black and white. Color corresponding to the filter wavelength was subsequently added back during image reconstruction to reflect the actual color observed.

TABLE 1.

Summary of antibody binding experiments and fluorescence results

| Type and order of antibody reagentsa

|

Fluorescence localization

|

Figure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | IgM | IgG | |

| 2H1 | F-GAM-IgM and R-GAM-IgG1 | None | None | NAb | Annular outer rim | NSc |

| 12A1 | F-GAM-IgM and R-GAM-IgG1 | None | None | Annular outer rim | NA | NS |

| 12A1 | F-GAM-IgM | 2H1 | R-GAM-IgG1 | Annular outer rim | Entire capsule, reduced in annular outer rim | 5a |

| 2H1 | R-GAM-IgG1 | 12A1 | F-GAM-IgM | Annular outer rim | Entire capsule including annular outer rim | 5b |

| 12A1 | 2H1 | F-GAM-IgM and R-GAM-IgG1 | None | Annular outer rim | Outer rim | 5c |

| 2H1 | 12A1 | F-GAM-IgG1 and R-GAM-IgG1 | None | Annular outer rim | Entire capsule including annular outer rim | 5d |

| 2H1-A | None | None | None | NA | Entire capsule including annular outer rim | 4a |

| 12A1-A | None | None | None | Annular outer rim | NA | 4b |

| 12A1-A | 2H1-A | None | None | Annular outer rim | Inner capsule, excluded from annular outer rim | 5e |

| 2H1-A | 12A1-A | None | None | Annular outer rim | Inner capsule, excluded from annular outer rim | 5f |

| 13F1 | F-GAM-IgM and R-GAM-IgG1 | None | None | Punctate outer rim | NA | NS |

| 13F1 | F-GAM-IgM | 2H1 | R-GAM-IgG1 | Punctate outer rim | Annular outer rim | 5g |

| 2H1 | R-GAM-IgG1 | 13F1 | F-GAM-IgM | Punctate outer rim | Entire capsule including annular outer rim | 5h |

| 13F1 | 2H1 | F-GAM-IgM and R-GAM-IgG1 | None | Punctate outer rim and near the cell wall | Entire capsule including annular outer rim | 5i |

| 2H1 | 13F1 | F-GAM-IgG1 and R-GAM-IgM | None | Punctate outer rim | Entire capsule including annular outer rim | 5j |

| 13F1-A | None | None | None | Punctate outer rim | NA | 4c |

| 13F1-A | 2H1-A | None | None | Punctate outer rim | Entire capsule, reduced in punctate outer rim | 5k |

| 2H1-A | 13F1-A | None | None | Punctate outer rim | Entire capsule, reduced in punctate outer rim | 5l |

2H1-A, 12A1-A, and 13F1-A denote Alexa dye-conjugated MAbs.

NA, not applicable.

NS, not shown in any figure.

RESULTS

Preservation of capsule in mouse lungs.

While studying aspects of C. neoformans pathogenesis in murine pulmonary infection by EM (16), we noted that yeast cell capsules were significantly better preserved in lung tissue than when fixed in aqueous cell suspension. Many experiments in our laboratory carried out over several years had shown that capsule preservation is poor when C. neoformans cells grown in vitro are embedded in plastic (unpublished results). We considered the possibility that this reflected capsule growth in vivo. Comparison of C. neoformans capsules in murine lung tissue at 5 min and 2 h after infection revealed comparable appearance and size consistent with preservation of the capsule structure by fixation in tissue.

Immunogold EM of MAb binding to C. neoformans.

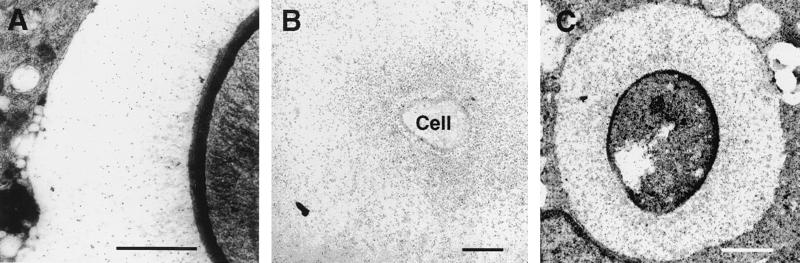

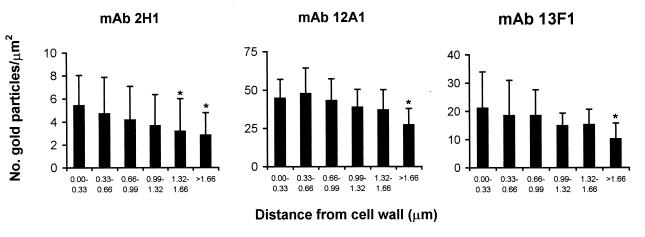

When C. neoformans cells in cut tissue sections were incubated with either MAb 12A1, 13F1, or 2H1 followed by detection with a gold-conjugated reagent, binding was noted throughout the capsule for all MAbs (Fig. 1), implying similar distributions of their epitopes. For each of these MAbs, the average number of gold balls per square micrometer was highest in the region of the capsule adjacent to the yeast cell wall and declined progressively as a function of the radius of the distance from the cell wall (Fig. 2). The gold ball density was significantly higher for the two IgM MAbs than for the IgG1 MAb (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

EM localization of MAbs 2H1 (A), 12A1 (B), and 13F1 (C) binding on C. neoformans cells in cut sections from a mouse lung visualized by postsectioning staining with immunogold. The yeast cell in panel A is in the extracellular space, whereas those in panels B and C are inside macrophages. Bars represent 1 μm. Images are representative of many micrographs obtained for each MAb.

FIG. 2.

Radial density of epitope for MAbs 2H1, 12A1, and 13F1 in the capsule of C. neoformans as demonstrated by immunogold labeling. The capsular polysaccharide in sections from infected mice was labeled with primary MAb followed by gold-conjugated secondary antibody, and the number of gold particles in 0.1 μm2 was determined in regions of the capsule at various distances from the cell wall on micrographs printed at a magnification of ×30,000. Numbers represent means, and error bars denote standard deviations. The following numbers of measurements were made at each distance: 0.0 to 0.33 μm, 28 for 2H1, 11 for 12A1, and 12 for 13F1; 0.33 to 0.66 μm, 28 for 2H1, 11 for 12A1, and 13 for 13F1; 0.68 to 0.99 μm, 25 for 2H1, 11 for 12A1, and 13 for 13F1; 0.99 to 1.32 μm, 23 for 2H1, 11 for 12A1, and 13 for 13F1, 1.32 to 1.66 μm, 19 for 2H1, 11 for 12A1, and 13 for 13F1; >1.66 μm, 11 for 2H1, 29 for 12A1, and 37 for 13F1. ∗, P < 0.05 by two-tailed Student's t test for measurement relative to the density of gold particles at 0.0 to 33 μm.

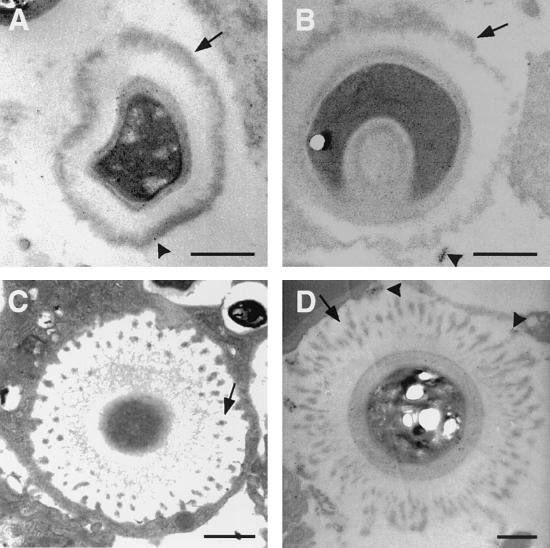

The observation that all three MAbs bound in similar manners to C. neoformans cells in cut tissue sections using immunogold detection contrasted with differences in IF patterns (annular for 2H1 and 12A1 and punctate for 13F1). Since the polysaccharide capsule for yeast cells in cut tissue sections is immobilized by embedding in plastic, this result implied that the punctate pattern produced by MAb 13F1 in solution reflected aggregation of antibody-antigen complexes when the capsule matrix was not fixed in place. To investigate this possibility, C. neoformans cells were incubated with either MAb 12A1 or 13F1 and then gold-labeled GAM-IgM, instilled into mice, fixed within 2 h, and studied by EM. For MAb 12A1, a continuous electron-dense outer layer was seen which presumably consists of antigen-antibody complexes localized to the surface of the capsule. For MAb 13F1, the pattern consisted of separated dense patches toward the polysaccharide capsule surface (Fig. 3). These patterns appear to be the EM equivalent of the annular and punctate IF patterns described for MAbs 12A1 and 13F1, respectively. In other experiments, C. neoformans was incubated with either MAb 12A1 or 13F1 alone, instilled into mouse lungs, fixed within 2 h, and then stained with gold-labeled GAM-IgM. Again, an electron-dense layer was observed near the surface of the capsule for MAb 12A1, whereas MAb 13F1 binding produced separated dense patches also near the capsule surface (not shown). Hence, immunogold staining confirmed the presence of IgM in the surface electron-dense layer observed when cells were preincubated with MAb 12A1 and the separated electron-dense patches were observed under similar circumstances with MAb 13F1. The intensity of immunogold staining was significantly reduced for those experiments where C. neoformans preincubated in MAb was instilled into mouse tracheas relative to studies that used cut sections, possibly reflecting immunoglobulin degradation by host or fungal proteases in vivo.

FIG. 3.

EM of C. neoformans cells preincubated with MAb 12A1 (A and B) or 13F1 (C and D) after inoculation into mouse lungs. Each arrow in panels A and B denotes electron-dense layer on the outer surface of C. neoformans after MAb 12A1 binding; arrows in panels C and D denote electron-dense deposits on the capsule of C. neoformans after MAb 13F1 binding. The patterns of electron-dense deposits were the same regardless of whether MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 were used alone or together with secondary GAM-IgM. Bars represent 1 μm.

IF MAb binding studies.

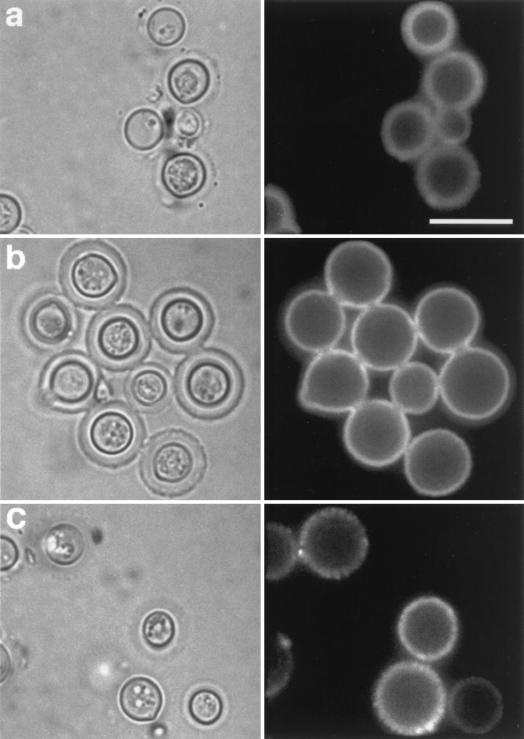

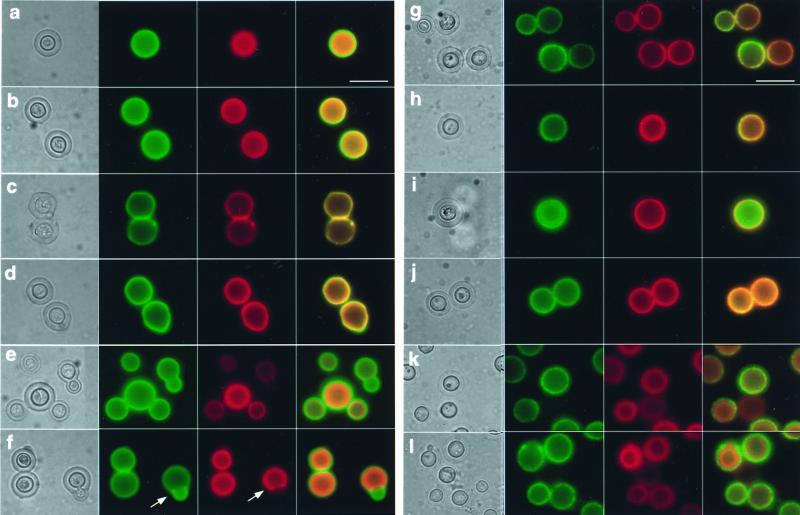

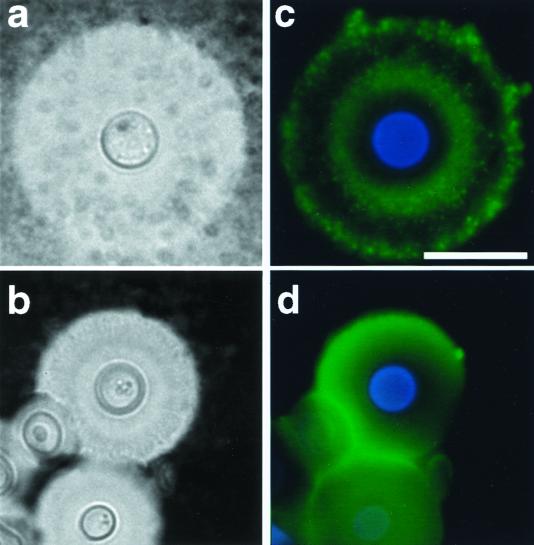

Although the EM studies suggested that the binding of MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 to the capsule of intact cells produced the patterns corresponding to the annular and punctate IF patterns, we explored the requirement for secondary antibodies for production of these patterns. Specifically, we investigated whether the secondary antibodies used in indirect IF studies mediated the antigen-antibody aggregation in the capsular matrix that appeared as annular and punctate binding by indirect IF. Direct IF using Alexa-conjugated MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 revealed annular and punctate IF patterns, respectively (Fig. 4b and c). This result is consistent with the EM findings and implies that the annular and punctate IF patterns are a consequence of the binding of the primary IgM MAbs to the capsular polysaccharide, not to the secondary antibody reagent.

FIG. 4.

Fluorescence patterns resulting from the binding of Alexa-conjugated MAbs 2H1 (a), 12A1 (b), and 13F1 (c) to C. neoformans cells. Bar represent 10 μm. Right, IF; left, light microscopy.

In contrast to MAbs 12A1 and 13F1, the localization of fluorescence for MAb 2H1 on the capsule differed depending on whether direct or indirect IF techniques were used (Fig. 5). Incubation of C. neoformans cells with MAb 2H1 conjugated to Alexa 546 produced a homogenous fluorescence throughout the entirety of the capsule, whereas addition of native MAb 2H1 followed by rhodamine- and fluorescein-conjugated secondary reagents produced fluorescence localized to the outer surface of the cell (Fig. 5). Since this observation implied that antibody binding to the capsule could modify or block the binding of secondary antibody, we investigated this possibility using combinations of the two IgM MAbs (12A1 and 13F1) and the IgG1 (2H1) in experiments where these MAbs were added sequentially using both conjugated and native MAbs (Fig. 5). The combination of MAbs 2H1 and 12A1 and 2H1 and 13F1 represented pairs of antibodies that bind to the same and different antigenic determinants, respectively (36). MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 have very similar apparent affinity for C. neoformans polysaccharide (22). MAb binding was detected by use of anti-GXM MAbs directly conjugated to Alexa dye or indirectly using isotype-specific F- and R-GAM reagents. The results are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 5.

IgM and IgG binding as detected by IF for C. neoformans cells stained with various combinations of MAbs 2H1, 12A1, and 13F1. For all panels, the order of images is light microscopy, fluorescein staining, rhodamine staining, and superposition of the fluorescein and rhodamine images. Panel letters are cross-referenced with conditions listed in Table 1. (a) MAb 12A1, F-GAM-IgM, MAb 2H1, R-GAM-IgG1; (b) MAb 2H1, R-GAM-IgG1, MAb 12A1, F-GAM-IgM; (c) MAb 12A1, MAb 2H1, F-GAM-IgM, R-GAM-IgG1; (d) MAb 2H1, MAb 12A1, R-GAM-IgG1, F-GAM-IgM; (e) MAb 12A1-Alexa 488, MAb 2H1-Alexa 546; (f) MAb 2H1-Alexa 546, MAb 12A1-Alexa 488; (g) MAb 13F1, MAb 2H1, F-GAM-IgM, MAb 2H1, R-GAM-IgG1; (h) MAb 2H1, R-GAM-IgG1, MAb 13F1, F-GAM-IgM; (i) MAb 13F1, MAb 2H1, F-GAM-IgM, R-GAM-IgG1; (j) MAb 2H1, MAb 13F1, F-GAM-IgM, R-GAM-IgG1; (k) MAb 13F1-Alexa 488, MAb 2H1-Alexa 546; (l) MAb 2H1-Alexa 546, MAb 13F1A1-Alexa 488. Yellow results from the superposition of green and red color and denotes areas where both MAbs are bound to the capsule. Rhodamine and Alexa 546 appear orange when superimposed with either FITC- or Alexa 488-stained images. Each arrow in panel f points to a bud which does not stain with MAb 2H1. Bar represents 10 μm.

Combining MAb 2H1 with either IgM did not significantly affect the localization of IgM fluorescence regardless of whether the IgG1 was added first or second (Fig. 5; Table 1). However, the localization of IgG1 fluorescence corresponding to MAb 2H1 binding in the C. neoformans capsule was altered by MAb 12A1, both when the IgG1 was added first and when it was added second. Specifically, when studied by direct IF in the presence of MAb 12A1, IgG1 fluorescence was observed primarily in the inner aspects of the capsule but not on the region bound by MAb 12A1, suggesting that MAb 12A1 competitively inhibited MAb 2H1 binding. Partial exclusion of IgG1 from the outer rim of the capsule was seen by indirect IF when the IgM and its secondary conjugated reagent were both added before the IgG1. Further, when MAb 2H1 was added first, followed by 12A1 and then the secondary reagents, IgG1 binding was observed throughout the capsule, suggesting that IgM-antigen complex binding by an anti-IgM could permit access to the IgG1. The combination of MAb 2H1 and 13F1 also modified the location of MAb 2H1 binding despite the fact that these MAbs bind different epitopes (22, 36). Remarkably, MAb 13F1 binding facilitated detection of MAb 2H1 binding throughout the capsule when IgG1 localization was detected by indirect IF (Fig. 5; Table 1). However, when directly labeled 13F1 and 2H1 MAbs were used in combination, the IgG1-related fluorescence was punctate in the outer rim, indicating yet another modification of MAb 2H1 binding by the IgM.

MAb 12A1 and 13F1 binding to C. neoformans cells from infected tissue.

One potential explanation for the lack of efficacy of MAb 13F1 in mouse protection studies (23) was that the epitope recognized by this MAb is not expressed by C. neoformans during infection. To investigate this possibility, we used IF to compare levels of MAb 12A1 and 13F1 binding to C. neoformans cells recovered from infected tissue and to cells from in vitro cultures. MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 bound to C. neoformans cells in lung homogenates with annular and punctate IF patterns, respectively (Fig. 6). Yeast cells from tissue had larger capsules, but the pattern of IF was qualitatively similar to that observed using C. neoformans cells grown in vitro.

FIG. 6.

India ink preparations (a and b) and indirect IF (c and d) of representative C. neoformans isolate from lungs of infected mice. Organ suspension was stained with 50 μg each of IgM MAbs 13F1 (a) and 12A1 (b) per ml. Scale bar = 10 μm (applies to both panels).

MAb binding to daughter and mother cells.

Analysis of MAb 12A1 binding to budding cells revealed comparable fluorescence intensities for both parent and budding cells (Fig. 5e). However, the fluorescence intensity of MAb 2H1 and 13F1 binding to C. neoformans budding cells was significantly lower than the intensity of binding to the mother cell (for 2H1, Fig. 5f; for 13F1, data not shown). This phenomenon was most apparent for cells from logarithmically growing cultures.

DISCUSSION

The C. neoformans capsular structure is easily disrupted during preparation for EM (1, 5, 13, 30). During previous studies of C. neoformans pulmonary infection (14), we noted that capsules were significantly better preserved when fixed in lung tissue than in solution. Since the C. neoformans capsule increases in size during infection (21, 29) and because iron availability (37) and carbon dioxide concentration (17) can affect capsule size, we investigated whether the difference in appearance reflected capsule growth in vivo. EM examination of C. neoformans cells at 5 min and 2 h revealed that the capsules were comparable in size and appearance (data not shown), consistent with the view that the detailed appearance of capsules noted in lung tissue reflected improved preservation. The mechanism by which fixing C. neoformans cells in tissue preserves the capsule is not understood. Tissue embedding may preserve the capsule by slowing the rate of dehydration or by retarding diffusion of the capsular polysaccharide away from the cell. Alternatively, tissue substances such as complement (14) or surfactant may bind to the capsule in the alveolar space and protect it during fixation and dehydration. Similarly, antibody or complement can protect the C. neoformans capsule from the dehydration steps that precede scanning EM (9). Another attraction of studying MAb binding to the capsule in tissue is that this technique approximates the state of C. neoformans cells at the time of experimental infection.

Immunogold EM of MAbs 12A1, 13F1, and 2H1 bound to sectioned capsule fixed in lung tissue revealed similar patterns of gold particle localization for all three antibodies. For all three MAbs, binding was observed throughout the capsule, but the density of binding was higher in the inner regions of the capsule. This effect was most pronounced for MAb 2H1. The regional differences in MAb binding to the capsule may reflect structural differences in the architecture of the capsule as a function of distance from the cell wall or a higher epitope density in the inner capsule due to closer packing of polysaccharide fibrils near the cell wall (31). Alternatively, there may be a concentration gradient in polysaccharide molecules as a function of distance from the cell wall such that the capsule is less dense in the outer regions. The density of gold balls was significantly higher for MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 than for MAb 2H1. This may reflect the higher avidity of IgM class antibodies as a result of their pentameric structure or a higher sensitivity for the IgM by the secondary reagents. On the basis of the immunogold EM study of MAb binding to cut sections, one might have expected similar binding patterns for each of these MAbs by other techniques. However, other studies have shown significant differences in the binding of MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 by IF (23), scanning EM (9), and transmission EM (23) when the MAbs are bound to yeast cells in solution. Presumably, these differences reflect the fact that the immunogold EM study used sectioned C. neoformans cells immobilized in a plastic support in a manner that would preclude aggregation of antigen-antibody complexes by polyvalent IgM or secondary antibody cross-linking after antibody binding. Furthermore, this method exposes epitopes in the inner portion of the capsule and allows unencumbered access to that epitope by the antibody reagent. The biological significance of antibody binding to internal epitopes is uncertain.

The similarities in immunogold EM after MAb 12A1 and 13F1 binding to C. neoformans in cut sections from tissue strongly suggested that the differences in IF observed for MAb binding in solution were a consequence of the formation of antigen-antibody complexes in the capsule matrix. To study this possibility, we investigated antibody localization by EM after binding in solution of MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 alone, followed by a secondary gold-labeled polyclonal antibody to mouse immunoglobulin. When MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 were added to C. neoformans in solution and the sample was then processed for EM, we observed electron-dense deposits in the capsule with and without the addition of GAM-IgM. The electron-dense deposits contained IgM and appear to be the EM equivalents of the annular and punctate patterns observed by IF. The only other study in the literature comparing immunogold EM and IF of a MAb to C. neoformans also reported comparable patterns when antibody was bound to cells in solution before microscopy (35). Hence, immunogold EM and IF appear to produce consistent antibody localization results when the EM samples are prepared by reacting C. neoformans with the antibody in solution before processing. The location of gold particles observed in this study differs from an earlier study that evaluated MAb 12A1 and 13F1 binding to cells in solution (23). That study showed MAb 12A1 binding primarily on the capsule surface and MAb 13F1 binding primarily inside the capsule. We attribute these differences to the different methodologies used and note that the presence of thick polysaccharide fibrils in the earlier micrographs suggest a preservation artifact.

When comparing antibody binding to C. neoformans in vitro and in vivo, it is important to consider the possibility that several variables could affect interpretation of the results. Alveolar spaces contain complement and surfactant components that may bind to the capsule and could conceivably affect the amount and location of antibody binding through steric and/or conformational effects. Although some effect of these endogenous humoral components cannot be totally excluded, we note that the antibody binding pattern (e.g., punctate and annular) was consistent for C. neoformans grown in vitro and recovered from lung homogenates. This suggests no interference in antibody-antigen complex formation in the capsule from other humoral substances in the binding of these MAbs. The possibility that endogenous antibody influences the results is extremely unlikely since this mouse strain does not make an appreciable antibody response (14), and control experiments revealed no secondary antibody binding to the capsule in the absence of primary MAb. Finally, tissue embedding may model C. neoformans infection in organs like the lung but may not accurately represent yeast cells in cerebrospinal fluid and serum, which are also found during infection. Despite these caveats, we believe that tissue embedding provides a new option for the study of capsule structure and antibody binding reactions.

Although the EM localization experiments strongly suggested that the different patterns were a property of the binding of primary IgM MAb to the capsule, we considered the possibility that the secondary antibody contributed to this effect by promoting the aggregation of primary antibody-antigen complexes. However, IF binding studies performed in solution using Alexa dye-labeled MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 revealed annular and punctate patterns, respectively, indicating that the effect was not due to antigen-antibody complex aggregation by the secondary antibody. The observation that MAb 12A1 localized to the surface despite the presence of its epitope throughout the capsule suggested that initial antibody binding at the surface could interfere with penetration of additional antibody to the deeper regions of the capsule. To investigate this possibility, MAbs 12A1 and 2H1 were added sequentially followed by secondary antibodies. In all combinations, MAb 12A1 bound preferentially to the outer rim, whereas the location of the apparent binding of MAb 2H1 was dependent on whether IgM was bound first and on the use of secondary reagents. Together, these results suggest that the annular pattern observed with MAb 12A1 represents preferential binding to the outer rim of the capsule. Whether this effect reflects a conformational change in the capsule that alters permeability or affinity is not known. We note that although several antibody combinations resulted in modification of the binding of subsequent primary or secondary antibody reagents, none of the antibodies tested completely blocked the binding of subsequent antibodies.

Capsule binding by MAb 2H1 to the capsule rim was reduced by MAb 12A1 when evaluated by direct IF, consistent with the observation that these two MAbs have similar, if not the same, epitope specificity (36) and that MAb 12A1 has higher affinity than MAb 2H1 (22). However, MAb 13F1 binding to the C. neoformans capsule also affected the binding of MAb 2H1 despite the fact that these MAbs bind to different epitopes (25, 36). Most interesting was the fact that combinations of MAbs 2H1 and 13F1 using directly labeled antibody resulted in punctate patterns of IgG localization at the capsule surface. Whether this reflects increased affinity of MAb 2H1 for polysaccharide in the vicinity of MAb 13F1-antigen complexes or a negative staining visual effect is uncertain. The variation in the pattern seen with the various antibody combinations indicates that the binding of one antibody to the capsule can modify the binding of antibodies of the same or different specificity.

Previous studies of C. neoformans cells grown in vitro have shown that the capsule over budding cells is thinner than that of the parent cell, indicating quantitative differences in the polysaccharide capsule of daughter and mother cells (5). However, to our knowledge, no qualitative differences in the type of polysaccharide capsule over daughter and mother cells have been described. The intensity of MAb 2H1 and 13F1 binding to the buds of replicating cells was significantly lower than for the mother cell. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the staining of daughter and mother cells by MAb 12A1. This observation suggests that the polysaccharide capsule over the bud is different from that over the mother cell. Since MAbs 12A1 and 2H1 are believed to bind to the same epitope in GXM on the basis of fine specificity mapping using peptide mimetics of GXM (36), this result could imply differences in the avidity of the IgM and IgG1 for the bud polysaccharide. Differences in avidity could arise if the pentameric IgM was more likely to form strong binding sites with the bud capsule than the bivalent IgG1. Alternatively, the differences in 12A1 and 2H1 binding for nascent buds can indicate differences in specificity. The lower affinity of MAb 2H1 for newly formed buds suggests a mechanism by which the newly formed offspring of replicating cells may escape the protective effects of IgG.

In summary, our results indicate that antibody binding to the C. neoformans capsule can modify the binding of subsequent antibodies to the polysaccharide antigen or to the primary antibody. In practical terms, this means that the pattern of antibody binding to the C. neoformans capsule can differ depending on whether direct or indirect IF techniques are used to visualize the location of antibody binding. The differences in IF pattern observed depending on the methodology used imply a need for caution when making conclusions regarding the location of antibody binding from studies that rely on single methods. In contrast, the combination of EM and solution IF studies can provide complementary information on the location of binding to a microbial capsule. The multitude of localization patterns obtained with just three MAbs depending on the reaction order and the methodology used to detect bound antibody highlight the complexity of antibody interactions with microbial capsules. One can anticipate significantly higher complexity for antibody-capsule interactions in vivo since antibody responses include antibodies of multiple specificities and isotype.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.F. and J.R. contributed equally to this work.

M.F. is supported by NIH award KO8AI01341. J.R. is supported by MARC predoctoral fellowship 5-F31-GM18951. T.R.K. is supported by grant RO1-AI14209. A.C. is supported by NIH awards AI33774, AI3342, and HL-59842-01 and a Burroughs Wellcome Development Therapeutics Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Doory Y. The ultrastructure of Cryptococcus neoformans. Sabouraudia. 1971;9:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolduan C F, Koopman J. Immune sera. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1917. pp. 67–134. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casadevall A, DeShaw M, Fan M, Dromer F, Kozel T R, Pirofski L. Molecular and idiotypic analysis of antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3864–3872. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3864-3872.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casadevall A, Mukherjee J, Devi S J N, Schneerson R, Robbins J B, Scharff M D. Antibodies elicited by a Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine have the same specificity as those elicited in infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;65:1086–1093. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassone A, Simonetti N, Strippoli V. Wall structure and bud formation on Cryptococcus neoformans. Arch Microbiol. 1974;95:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherniak R, Sundstrom J B. Polysaccharide antigens of the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1507–1512. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1507-1512.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleare W, Brandt M E, Casadevall A. Monoclonal antibody 13F1 produces annular immunofluorescent patterns on Cryptococcus neoformans serotype AD isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3080. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.3080-3080.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleare W, Casadevall A. The different binding patterns of two IgM monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A and D strains correlates with serotype classification and differences in functional assays. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:125–129. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.125-129.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleare W, Casadevall A. Scanning electron microscopy of encapsulated and non-encapsulated Cryptococcus neoformans and the effect of glucose on capsular polysaccharide release. Med Mycol. 1999;37:235–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dromer F, Mathoulin S, Dupont B, Laporte A. Epidemiology of cryptococcosis in France: a 9-year survey (1985–1993) Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:82–90. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dromer F, Salamero J, Contrepois A, Carbon C, Yeni P. Production, characterization, and antibody specificity of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1987;55:742–748. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.742-748.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckert T F, Kozel T R. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1895–1899. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1895-1899.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards M R, Gordon M A, Lapa E W, Ghiorse W C. Micromorphology of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:766–777. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.3.766-777.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldmesser M, Casadevall A. Effect of serum IgG1 against murine pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 1997;158:790–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldmesser M, Casadevall A. Mechanism of action of antibody to capsular polysaccharide in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Front Biosci. 1998;3:136–151. doi: 10.2741/a270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldmesser M, Casadevall A, Kress Y, Spira G, Orlofski A. Eosinophil-Cryptococcus neoformans interactions in vivo and in vitro. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1899–1907. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1899-1907.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granger D L, Perfect J R, Durack D T. Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Regulation of capsule synthesis by carbon dioxide. J Clin Investig. 1985;76:508–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI112000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozel T R. Activation of the complement system by pathogenic fungi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:34–46. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozel T R, deJong B C H, Grinsell M M, MacGill R S, Wall K K. Characterization of anti-capsular monoclonal antibodies that regulate activation of the complement system by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1538–1546. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1538-1546.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levitz S M, DiBenedetto D J, Diamond R D. A rapid fluorescent assay to distinguish attached from phagocytized yeast particles. J Immunol Methods. 1987;101:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Littman M L. Capsule synthesis by Cryptococcus neoformans. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1958;20:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.2164-0947.1958.tb00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee J, Casadevall A, Scharff M D. Molecular characterization of the antibody responses to Cryptococcus neoformans infection and glucuronoxylomannan-tetanus toxoid conjugate immunization. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1105–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee J, Nussbaum G, Scharff M D, Casadevall A. Protective and non-protective monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans originating from one B-cell. J Exp Med. 1995;181:405–409. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee S, Feldmesser M, Casadevall A. J774 murine macrophage-like cell interactions with Cryptococcus neoformans in the presence and absence of opsonins. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1222–1231. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nussbaum G, Cleare W, Casadevall A, Scharff M D, Valadon P. Epitope location in the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule is a determinant of antibody efficacy. J Exp Med. 1997;185:685–697. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pirofski L, Casadevall A. Antibody immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans: paradigm for antibody immunity to the fungi? Zentbl Bakteriol. 1996;284:475–495. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pirofski L, Lui R, DeShaw M, Kressel A B, Zhong Z. Analysis of human monoclonal antibodies elicited by vaccination with a Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan capsular polysaccharide vaccine. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3005–3014. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3005-3014.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodes J C, Wicker L S, Urba W. Genetic control of susceptibility to Cryptococcus neoformans in mice. Infect Immun. 1980;29:494–499. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.2.494-499.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivera J, Feldmesser M, Cammer M, Casadevall A. Organ-dependent variation of capsule thickness in Cryptococcus neoformans during experimental murine infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5027–5030. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.5027-5030.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakaguchi N. Ultrastructural study of hepatic granulomas induced by Cryptococcus neoformans by quick-freezing and deep-etching method. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1993;64:57–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02915096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakaguchi N, Baba T, Fukuzawa M, Ohno S. Ultrastructural study of Cryptococcus neoformans by quick-freezing and deep-etching method. Mycopathologia. 1993;121:133–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01104068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlagetter A M, Kozel T R. Opsonization of Cryptococcus neoformans by a family of isotype-switch variant antibodies specific for the capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1914–1918. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1914-1918.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Syme R M, Bruno T F, Kozel T R, Mody C H. The capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans reduces T-lymphocyte proliferation by reducing phagocytosis, which can be restored with anticapsular antibody. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4620–4627. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4620-4627.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Todaro-Luck F, Reiss E, Cherniak R, Kaufman L. Characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan polysaccharide with monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3882–3887. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.12.3882-3887.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Todaro-Luck F, White E H, Reiss E, Cherniak R. Immunoelectronmicroscopic characterization of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Cell Probes. 1989;3:345–361. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(89)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valadon P, Nussbaum G, Boyd L F, Margulies D H, Scharff M D. Peptide libraries define the fine specificity of anti-polysaccharide antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:11–22. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vartivarian S E, Anaissie E J, Cowart R E, Sprigg H A, Tingler M J, Jacobson E S. Regulation of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide by iron. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:186–190. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vecchiarelli A, Casadevall A. Antibody-mediated effects against Cryptococcus neoformans: evidence for interdependency and collaboration between humoral and cellular immunity. Res Immunol. 1998;149:321–333. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vecchiarelli A, Retini C, Monari C, Casadevall A. Specific antibody to Cryptococcus neoformans alters human leukocyte cytokine synthesis and promotes T-cell proliferation. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1244–1247. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1244-1247.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]