Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had substantial negative impacts on the global economy. While all sectors of the economy are expected to be adversely affected, the economic implications of this pandemic for the hotel industry have not yet been widely investigated. The purpose of this study is to examine the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the U.S. hotel industry. The results showed that daily room OCC, ADR and RevPAR have plunged about 74%, 47% and 86%, respectively. Although the impact is observed across all hotel segments, economy-scale hotels were more resilient, whereas luxury-scale hotels experienced the largest decline. Also, chain-managed hotels are the most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to franchise and independent hotels. Quantifying the magnitude of this impact, we found that the U.S. hotel industry's revenue losses accumulated to over $30 billion between March-2020 and May-2020. Implications for practitioners, policy-makers, and researchers are discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Pandemic, Hotel industry, Economic impact, United States

1. Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic has reminded the world of hospitality the fragile nature of the hotel industry to external shocks such as wars, political upheavals, natural disasters, pandemics and financial crises (Kuo, Chen, Tseng, Ju, & Huang, 2008; Chan & Lam, 2013; Novelli, Burgess, Jones, & Ritchie, 2018). These shocks entail catastrophic disruptions on hotel operations and severely damage the hotel industry of the effected countries by affecting domestic and international tourism and lodging demand. Particularly, pandemics (health crises in general) induce a more global and wide-spread impact due to risk of transmission across countries and persistence until an effective vaccine or treatment is developed to prevent and cure the disease. At times of prolonged health crises, increasing fear of transmission in the communities and growing uncertainty in the business environment lead to paramount shifts in the consumer behavior, which forces companies to device effective business strategies to successfully weather the storm and continue their operations. The recent COVID-19 pandemic with its severe financial and operational challenges on the hotel industry has underlined the importance of effective business strategies to operate and remain resilient in an increasingly chaotic business environment.

As the COVID-19 has drastically changed the course of life, business and the trajectory of the overall economy, the financial resilience and operational continuity of economic sectors have seriously been challenged. COVID-19 has had remarkably adverse impacts on service industries such as restaurants, bars, theme parks, brick-and-mortar retailers, airlines, and hotels and other lodging establishments. In particular, the hotel industry—the torchbearer of the U.S. economy—was one of the hardest-hit industries by the COVID-19 pandemic as both domestic and international travel were restricted to contain the spread of the coronavirus. The sensitive nature of the hotel industry to external shocks, combined with their higher fixed asset, high fixed cost, and higher leverage structure compared to other service sectors have made the hotel industry even more vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic (Kizildag, 2015; Kizildag & Ozdemir, 2017). While the American Hotel and Lodging Association (AH&LA) has estimated that U.S. hotels will lose billions of dollars due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a comprehensive and accurate picture of this impact to the U.S. hotel industry is yet not available. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the U.S. hotel industry and explain the varying effects this unprecedented pandemic on the different segments of the hotel industry within the chaos theory framework (Lewin, 1993). Hotel companies operate in a complex business environment that encompasses various stakeholders (e.g. airlines, transportation companies, restaurants, entertainment companies, guests, employees and local authorities) that are all somewhat connected to each other in their own way. Thus, to understand the impact of a surging pandemic on the hotel industry, it is important to adopt a comprehensive perspective and discuss the industry-wide effects adhering to the complex business environment as suggested by the chaos theory. To achieve this objective, we first measure the changes in key hotel performance measures (e.g., OCC, ADR, RevPAR, etc.) in parallel with the timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S., between March 1 and May 31, 2020. Second, we compare the changes in key hotel performance measures across hotel segments (i.e., economy, midscale, upper midscale, up-scale, upper upscale, and luxury) and across hotel operational structures (i.e., chain-managed, franchise, and independent). Third, we examine the extent to which the changes in key hotel performance measures are significantly different across hotel segments and hotel operational structures for the study period. Finally, we calculate the potential revenue losses of the overall hotel industry in the U.S., and the potential revenue losses across hotel segments and hotel operational structures for the study period.

This study makes significant contributions to the extant literature. Analyzing the hotel industry's operational performance during the initial stages of the COVID-19 allows us to quantify the magnitude of this global pandemic's financial impact on the U.S. hotel industry, which is the first step in enabling both the industry—companies and trade organizations— and policy-makers, and destinations to develop appropriate strategies to cope with its adverse impacts. Also, our analysis provides a template for academics, practitioners and policy-makers for evaluating the economic effects of other pandemics that may surface in the future. Furthermore, investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on different hotel segments and hotels with different operational structures offer deeper insights to develop more specific preparedness and recovery strategies for companies operating in different hotel segments.

2. Literature review

2.1. Economic crises in the tourism and hospitality industry

In the past two decades, major disruptive events- September 11th (9/11), the SARS outbreak in 2003, the global financial crisis in 2008/2009 and the 2015 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak have had devastating effects on the world tourism and hospitality industry (Gössling, Scott, & Hall, 2020; Hall, 2010). Following the September 11 terror attacks, demand for travel rapidly dropped along with the hotel industry's performance. Airlines were halted and traveler confidence diminished due to insecurity and fear of recursive attacks (Arana & León, 2008; Drakos & Kutan, 2003; Kosova & Enz, 2012; Pizam, 1999). In fact, U.S. hotel bookings declined by 20–50% in the first 3 months following 9/11 (Goodrich, 2002). Relatedly, hotel occupancy rates, average daily rate, and RevPAR decreased by about 4.17%, $1.00, and $4.16, respectively in the U.S. following 9/11 (Kosova & Enz, 2012). Considered one of the most significant infectious disease outbreaks of the 21st century, SARS in 2003, was mostly contained in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Canada (Gössling et al., 2020). However, the global economic impact of SARS was estimated at $100 billion, of which China alone suffered a loss of $48 billion (McKercher & Chon, 2004). In Mainland China, the lowest occupancy rate was reported as 18% in May 2003 before recovering to a pre-SARS level of 67% in August 2003 (Hospitalitynet, 2020). According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTCC), following the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the growth rate of travel and tourism industries declined by 1% in terms of GDP. Relatedly, in anticipation of declines in tourism and travel, stock prices drop in hospitality industries. Effects of the 2007/2008 financial crisis on the U.S. hotel industry were economically significant, with $0.28 and $0.70 decreases in ADR and RevPAR respectively (Kosova & Enz, 2012).

2.2. COVID-19 and the hotel industry

The novel coronavirus has spread across the world at an unprecedented rate, which has caught governments off guard and unprepared for such an impactful pandemic. Strict regulations such as state of emergencies, stay-at-home orders, and partial or complete border closings have had caused major shocks to overall economic activity. The immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the overall global economy has been devastating thus far. As with prior crises, tourism and hospitality industries are the most significantly affected by COVID-19. In week ending June 282,020, domestic and international air travel in the U.S. was down 76% and 95% respectively compared to the same week of 2019 (Airlines for America, 2020). Revenues of food services and drinking places decreased nearly half from $65.4 billion in February to $32.4 billion in April, recording the smallest volume since March 2005 (National Restaurant Association, 2020). As many restaurants and drinking places remained closed per state orders, employment in the restaurant industry has plummeted more than 40% (Dixon, 2020).

The hotel industry has also experienced the dramatic economic impact of the spread of COVID-19. Certainly, the potential impact on the hotel industry was somewhat expected, as many countries and states implemented strict stay at home orders. While hotels were not mandated to shut down their operations, the lack of demand due to the immense risk of virus contamination forced many properties to pause their operations. According to Smith Travel Research (STR) study, hotel room occupancy was down as much as 96%, 68%, 67%, 59%, and 48% in Italy, China, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Singapore, respectively, by March 21, 2020 (Sorells, 2020). The pandemic has also resulted in significant job losses in the hotel industry through furloughs and layoffs, which account for nearly 3.9 million jobs since the pandemic began (AHLA, 2020). Moreover, the impact will continue into the next several months. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has forecasted a decline of 20–30% in international arrivals in 2020 (UNWTO, 2020). With the negative prospects predicted in the first half of 2020, the hotel industry was already in turbulence and utilized every resource available to survive in a chaotic business environment.

Although initial evidence indicates the devastating economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the U.S. hotel industry, its exact magnitude and the implications of these effects have not been comprehensively investigated. Specifically, we contend that these impacts may not be homogenous across hotel segments and across hotels with different operational structures. Thus, it is of great importance to quantify the financial magnitude of these nuanced impacts, which can help guide the hotel industry and policy-makers in developing appropriate strategies and policies to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic and provide a template to evaluate other potential pandemics that may surface in the future.

2.3. Theoretical underpinnings

The prevalence of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the ultimate need for forward-looking recovery strategies and plans that support operational stabilization, financial re-emergence, revenue generation, coping mechanisms of employment structure for the affected labor force, marketing/re-branding policies and efforts for the lodging establishments. Phases in economic crisis resilience plans and frameworks indicate key policies and strategies that attempt recovery through best possible “return to normal” operations, and later a resumed-growth (i.e., restoring the guest and tourism traffic) in the operations (Campiranon & Scott, 2014; Faulkner & Vikulov, 2001; Laws, Prideaux, & Chon, 2007; Mair, Ritchie, & Walters, 2016). From a theoretical point of view, these resilience and recovery attempts of the companies can be explained by the chaos theory, which has emerged as a useful framework for understanding organizational crisis and communication/strategy.

First off, chaos means more than a simple disorder or confusion, as it deals particularly with how something changes over time, whether it is the weather, the Dow-Jones Industrial average, food prices, or the size of insect populations (Williams, 1997). It is the theory that provides a useful framework for understanding organizational crisis as a whole. More specifically, chaos theory links organizational crisis and its communicative dimensions, to broader notions of system stability and instability, and subsequent decline and renewal (Murphy, 1996). The theory also aims to understand systems that do not behave in a linearly predictable, conventional cause-and-effect manner (Murphy, 1996). The chaos theory is based on the idea of sensitive dependence on initial conditions (also known as the Butterfly Effect), where small changes at the beginning of an emerging event could quickly turn into big changes at the end (Gleick, 2008). The notion of the Butterfly Effect was first introduced by Lorenz (1972) and questioned whether the single flap of a butterfly's wing in Brazil could be instrumental in generating a tornado in Texas. If this hypothesis is true and supported with strong validity, the created instability would present problems for the predictability of events. Taken together, the main postulation of the chaos theory is an appropriate theoretical framework to rely on when exploring companies' changing priorities and creation of new business strategies during and in the aftermath of a crisis such as an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Linking the prism and principles encapsulated by chaos theory to the management and resistance of the COVID-19 pandemic, and considering that the entire lodging, accommodation, and hotel industry will subsist after the COVID-19 pandemic, the chaos theory may provide clues as to what to expect at the end of chaotic times. This theory in this instance may predict a scenario of business restoration and resilience resembling the usual (largely mimicking the conventional normal, which is the pre-crisis/disaster state), or one that may move towards a totally new turning point (and perhaps more effective) arrangement in the way hotels operate. For instance, managing perceived business and operating risk, as the initial conditions and/or small bundles created by COVID-19, may be very well the first foundational focus followed by financial strategies such as cost reduction, revenue enhancement, and cash management in pandemic revamping attempts for the hotel establishments (Rivera, Kizildag, & Croes, 2021). Acknowledging that the chaos theory provides a theoretical umbrella for a new set of operations priorities and strategies, the following sections suggest how lodging companies and establishments may be successful in a “new normal” operations setting by focusing on a need for financial recovery strategies such as inventory concerns, cost reduction, revenue enhancement, capital restructuring, and cash management.

3. Methodology

The study's sample consists of all hotels that provide data to STR, which is about 74% of the hotel census in the United States during the study period. The hotel data consists of both monthly and daily data. Although we utilize the hotel data for the period 2017–2020 for comparative analysis, the primary focus of the study is the daily data for the period between March 1, 2020 and May 31, 2020, which is the most recent time period for which the data was available. During this period, the sample consists of 92 daily observations.

The variables of interests in this study are occupancy rate (i.e., OCC), hotel average daily rate (i.e., ADR), hotel room revenue per available room (i.e., RevPAR), hotel room supply (i.e., total number of rooms available), hotel room demand (i.e., total number of rooms sold), and hotel room revenue (i.e., total room revenue), which are commonly utilized key performance measures of the hotel industry. While the U.S. level OCC, ADR, RevPAR, hotel room supply, hotel room demand, and hotel room revenue variables are the main focus of this study, these variables are also utilized based on hotel segments (i.e., economy, midscale, upper midscale, up-scale, upper upscale, and luxury) and hotel operational structure (i.e., chain-managed, franchise, and independent) levels. The hotel performance measures were provided by Smith Travel Research (STR). We also obtained data about daily coronavirus cases and deaths in the U.S. from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX).

Due to the nature of the event (i.e., COVID-19) and the relatively short time period associated with it, the empirical approach in this study primarily consists of exploratory analysis. In this regard, we first measure the changes in key hotel performance measures (e.g., OCC, ADR, RevPAR, etc.) in parallel with the timeline of COVID-19 in the U.S. This set of analyses allows us to exhibit the impact of COVID-19 on the U.S. hotel industry during the study period. We also compare the changes in key hotel performance measures across hotel segments (i.e., economy, midscale, upper midscale, up-scale, upper upscale, and luxury) and across hotel operational structures (i.e., chain-managed, franchise, and independent). While these preliminary analyses are necessary to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 on the U.S. hotel industry, they do not provide statistical inferences. Thus, we further utilize mean difference analyses to examine the extent to which the changes in key hotel performance measures are significantly different across hotel segments and hotel operational structures during the study period. Additionally, we calculated the potential revenue losses of the overall hotel industry in the U.S., and the losses across hotel segments hotel operational structures during the study period to quantify the exact financial magnitude of COVID-19. Table 1 presents the summary statistics of the study variables; the daily U.S. data for the period between March 1, 2020 and May 31, 2020, and the correlation matrix for these variables.

Table 1.

Summary statistics: aggregate of daily U.S. data between March 1 and May 31, 2020.

| Variables | Descriptive statistics |

Correlation matrix |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Covid-19 cases | Covid-19 deaths | OCC | ADR | RevPAR | Supply | Demand | |

| Covid-19 Cases | 19,555 | 23,224 | 11,327 | 1 | ||||||

| Covid-19 Deaths | 1137 | 1220 | 838 | 0.88a | 1 | |||||

| OCC | 0.326 | 0.296 | 0.119 | −0.69a | −0.52a | 1 | ||||

| ADR | 85.06 | 77.78 | 17.25 | −0.86a | −0.72a | 0.91a | 1 | |||

| RevPAR | 29.67 | 22.83 | 18.75 | −0.75a | −0.60a | 0.98a | 0.96a | 1 | ||

| Supply | 4,955,235 | 4,862,967 | 298,498 | −0.87a | −0.86a | 0.49a | 0.71a | 0.57a | 1 | |

| Demand | 1,637,028 | 1,429,887 | 678,182 | −0.75a | −0.60a | 0.99a | 0.94a | 0.99a | 0.58a | 1 |

| Revenue⁎ | 150 | 112 | 104 | −0.78a | −0.63a | 0.97a | 0.97a | 0.61a | 0.61a | 0.98a |

Notes: a indicates 1% statistical significance level.

Millions.

4. Results

4.1. The impact of COVID-19 on the overall U.S. hotel industry

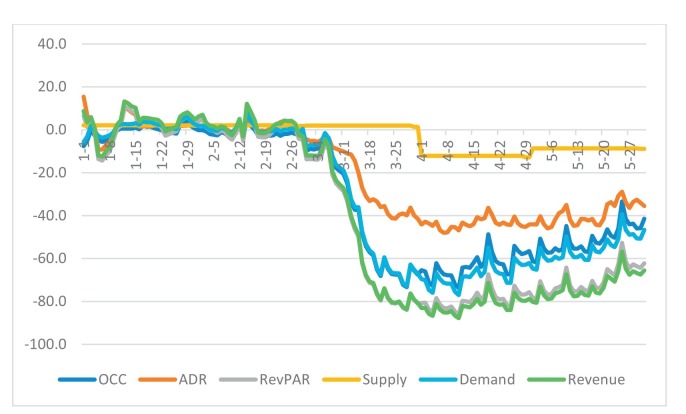

To highlight the significance of the impact of COVID-19 on key hotel performance measures, we examined the changes in these measures relative to same period last year (i.e., 2019). Fig. 1 illustrates these findings. Initial examination shows that the COVID-19 pandemic does not appear to have an impact on the U.S. hotel industry during the months of January and February 2020; the key performance measures remained relatively stable. A closer examination of the data shows that hotel room OCC, ADR, RevPAR, demand, and revenues started to decline since March 1, 2020.

Fig. 1.

Percent Changes in U.S. Hotel Daily Performance Measures Between January 1, 2020 and May 31, 2020 compared to same date last year.

While hotel room supply remained constant during March 2020, many hotel rooms were removed from the U.S. hotel market since the beginning of April. There was approximately 12% less hotel room supply on the market in April 2020 compared to the same month last year. The changes in OCC, ADR, RevPAR, demand, and revenues were more dramatic during this period compared to that of hotel room supply. The decline in hotel room OCC, ADR, RevPAR, demand, and revenues reached its highest levels on April 11, at 74%, 47%, 86%, 77%, and 88%, respectively, compared to same date last year (i.e., 2019).

While hotel performance measures started to improve after April 11, they were still significantly lower as of May 31, 2020, compared to the same date last year. That is, the decline in hotel room OCC, ADR, RevPAR, supply, demand and revenues were about 41%, 35%, 62%, 9%, 47%, and 66%, respectively, compared to same date last year (i.e., May 31, 2019).

4.2. The impact of COVID-19 on hotel segments

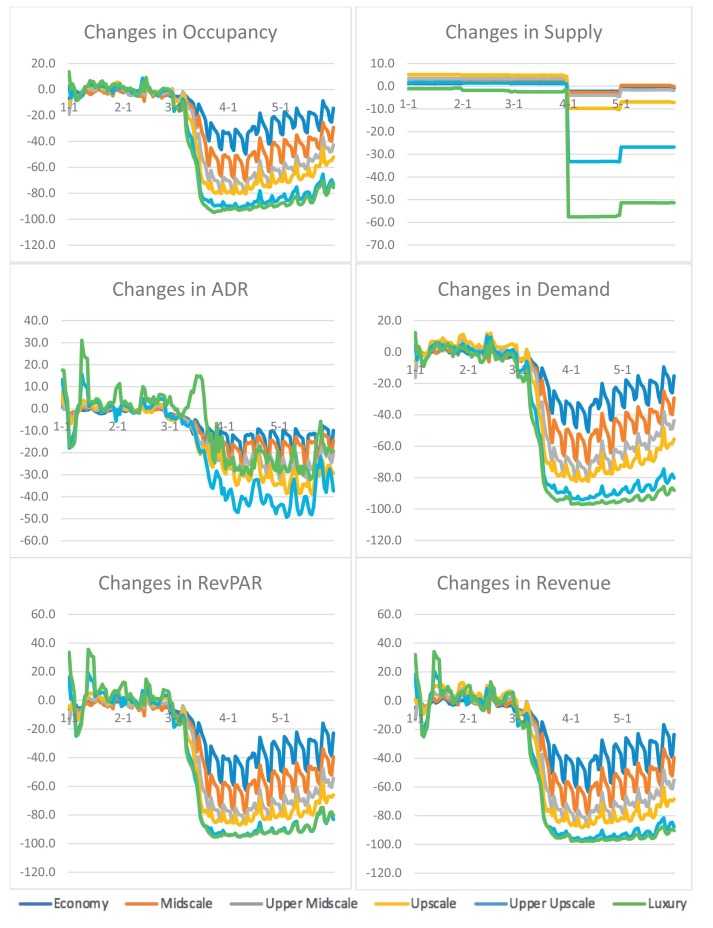

While the initial analysis showed that the U.S. hotel industry experienced large decreases in key hotel performance measures, the impact of COVID-19 on different hotel segments and operational structures may not be uniform. Fig. 2 presents the findings from our examination of the key hotel performance measures across hotel segments (i.e., economy, midscale, upper midscale, up-scale, upper upscale, and luxury).

Fig. 2.

Percent Changes in Hotel Segments' Daily Performance Measures Between January 1, 2020 and May 31, 2020 compared to same date last year.

The results show a trend that is similar to that of the overall U.S. hotel industry. However, significant differences are observed across hotel segments. The economy segment appears to be the least affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by the midscale and upper midscale segments. While upscale hotels are also affected relatively more than the economy, midscale, and upper midscale segments, the impact of COVID-19 on upper upscale and luxury hotel segments is much larger. More specifically, on April 11, which records the highest decline in key hotel performance measures compared to the same date last year, hotel occupancy rates decreased 47%, 68%, 80%, and 80% for economy, midscale, upper midscale, and upscale hotel segments, respectively. The upper upscale and luxury hotel segments experienced 90% and 92% declines in hotel room occupancy respectively. Similar patterns of declines are observed for other hotel key performance measures across the various hotel segments, indicating that, in general, as we move higher up the hotel chain scale segment, the more severe the impacts of COVID-19 on the segment's key performance measures.

While the preliminary findings show substantive evidence that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic varies across hotel segments, we further analyzed the mean differences of the key hotel performance measures across hotel segments to provide statistical inferences for these differences. Table 2 presents these results.

Table 2.

Mean scores and mean difference tests: hotel segments.

| Hotel segments | Hotel performance measures |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCC | ADR | RevPAR | Supply | Demand | Revenue | |

| Economy | −24.76 (11.29) | −12.48 (5.94) | −33.60 (13.84) | −0.59 (1.40) | −25.14 (11.77) | −33.90 (14.29) |

| Midscale | −41.54 (16.43) | −15.41 (6.56) | −49.59 (18.11) | 0.15 (2.30) | −41.24 (17.42) | −49.28 (19.05) |

| Upper Midscale | −54.64 (20.19) | −20.77 (8.13) | −62.70 (21.30) | −0.71 (3.14) | −54.63 (21.36) | −62.57 (22.43) |

| Upscale | −61.89 (20.79) | −25.20 (9.91) | −69.93 (21.48) | −3.90 (6.35) | −62.74 (22.43) | −70.35 (23.15) |

| Upper Upscale | −74.79 (22.32) | −32.30 (14.06) | −80.35 (22.86) | −19.37 (15.15) | −77.88 (23.80) | −82.19 (23.94) |

| Luxury | −78.88 (22.43) | −16.59 (12.90) | −80.76 (23.20) | −36.84 (24.83) | −83.85 (23.32) | −84.69 (23.82) |

| Analysis of Variance | ||||||

| F-test | 103.61a | 48.52a | 75.56a | 137.24a | 107.96a | 77.27a |

Notes: a indicates 1% statistical significance. Standard deviations are in parentheses. The numbers represent % changes. All post hoc tests of mean differences are statistically significant at 1% statistical significance level with few exceptions. Detailed results of the post hoc tests are not presented to conserve space. They are available upon request.

The results show the mean values of the changes in hotel room OCC, ADR, RevPAR, supply, demand, and revenue across hotel segments between March 1 and May 31, 2020, compared to the same period last year. The results from the Bartlett's test for equal variances showed that the variances in each group are equal. We also applied the Shapiro-Wilk test of normal distribution of data. While some of the variables were slightly left- or right-skewed, the one-way ANOVA technique still produces reliable results that is robust to skewness (Lix, Keselman, & Keselman, 1996). Accordingly, the results from the one-way ANOVA tests show that the mean differences for most key performance measures across the hotel segments are statistically significant at the 1% level. These findings are consistent with our preliminary analysis that luxury and upper upscale hotels experienced the largest negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. While economy and midscale hotels were also adversely affected, the impacts were lower in magnitude across all key performance measures. For example, on average, economy hotels experienced a 33.6% decrease in RevPAR, while luxury hotels' RevPAR decreased by 80.76% during the March 1 to May 31 period in 2020, compared to same period last year.

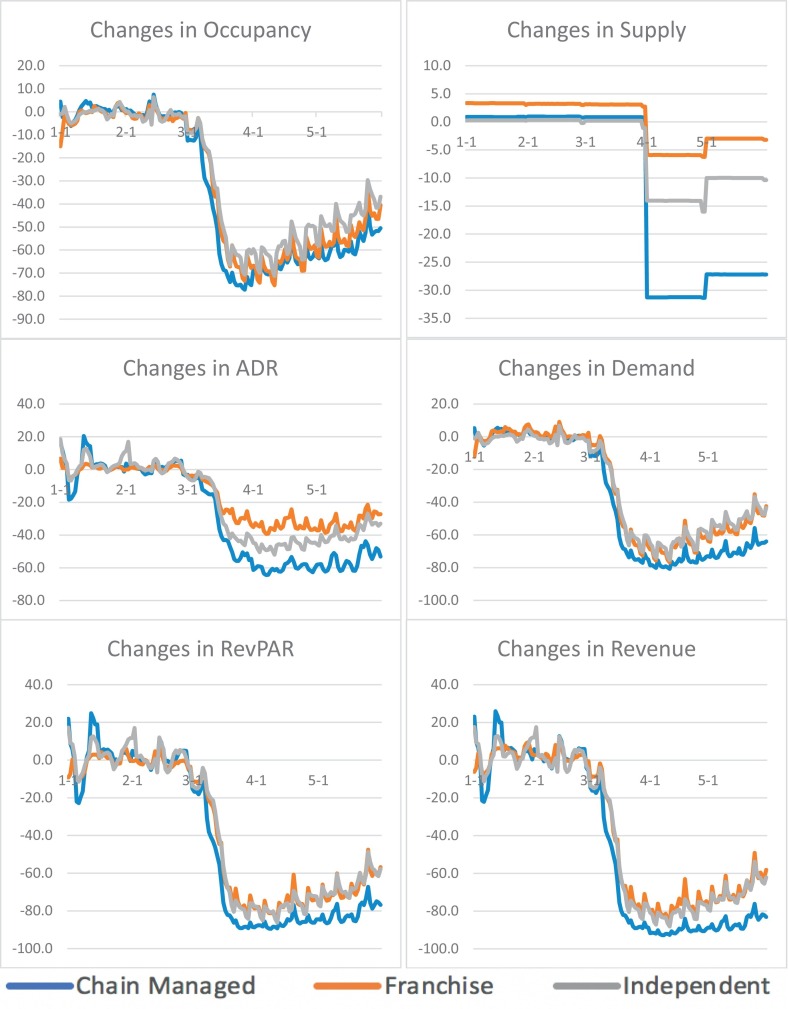

4.3. The impact of COVID-19 across hotel operational structures

We also analyzed the extent to which the impact of COVID-19 varies across hotel operational structures (i.e., chain-managed, franchise, and independent). Fig. 3 illustrates these findings. While the overall pattern of findings is similar to that for the overall U.S. hotel market, there are important differences across hotel operational structures in terms of the impact of COVID-19 on key hotel performance measures. In general, chain-managed hotels are found to be the most affected by the pandemic, followed by franchise and independent hotels. While franchise and independent hotels appear to have experienced similar impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are some notable differences. For example, RevPAR has declined about 89%, 84% and 86% in chain-managed, franchise and independent hotels, respectively, on April 11, which is the date with the largest decline in key hotel performance measures compared to same date last year. While chain-managed hotels appear to be more resilient on OCC, they experienced higher decreases in ADR and RevPAR compared to franchise and independent hotels. Most strikingly, the magnitude of the decline in room supply in chain-managed hotels—at approximately 31% —is much higher compared to franchise and independent hotels, at approximately 6% and 14% respectively on April 11.

Fig. 3.

Percent Changes in Hotel Operational Structures' Daily Performance Measures Between January 1, 2020 and May 31, 2020 compared to same date last year.

We also analyzed whether the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is statistically significantly different between chain-managed, franchise, and independent hotels. Table 3 present these results. The results of the one-way ANOVA test show that the mean differences of changes in hotel room OCC, ADR, RevPAR, supply, demand, and revenue across hotel.

Table 3.

Mean scores and mean difference tests: hotel operational structure.

| Hotel operational structure | Hotel performance measures |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCC | ADR | RevPAR | Supply | Demand | Revenue | |

| Chain-Managed | −57.22 (17.16) | −48.58 (17.76) | −75.38 (20.91) | −19.06 (14.36) | −64.50 (19.54) | −78.44 (22.29) |

| Franchise | −52.06 (18.53) | −27.87 (10.47) | −63.68 (20.79) | −1.91 (3.77) | −52.61 (19.75) | −63.93 (21.92) |

| Independent | −47.14 (14.77) | −35.96 (14.17) | −63.91 (21.19) | −7.96 (6.04) | −50.88 (18.22) | −66.07 (21.98) |

| Analysis of Variance | ||||||

| F-test | 7.53a | 47.99a | 9.35a | 81.25a | 13.73a | 11.60a |

Notes: a indicates 1% statistical significance. Standard deviations are in parentheses. The numbers represent % changes. All post hoc tests of mean differences are statistically significant at 1% statistical significance level with few exceptions. Detailed results of the post hoc tests are not presented to conserve space. They are available upon request.

operational structures between March 1 and May 31, 2020, as compared to same period last year, are statistically significant at the 1% level.

These results support the findings from the initial analysis that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was the highest in magnitude in chain-managed hotels compared to franchise and independent hotels. Although franchise and independent hotels are also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, the effects were smaller compared to those of chain-managed hotels across all key measures (i.e., OCC, ADR, RevPAR, supply, demand, and revenue). For instance, on average, franchise and independent hotels' RevPAR decreased by 63.93% and 66.07%, whereas chain-managed hotels experienced a drop of 78.44% between March and May. While the impact of COVID-19 on franchise and independent hotels are largely similar in magnitude, major differences are observed in changes in OCC, ADR and supply. While franchise hotels experienced a larger decline in OCC, independent hotels had a higher drop in ADR and supply.

4.4. The financial impact of COVID-19 on U.S. hotels

The overall impact of COVID-19 on the U.S. hotel industry is evident based on our previous analyses. In this section, we quantify the magnitude of its financial impact on the industry overall, and across hotel segments and operational structures. For this purpose, we analyzed total hotel room revenues generated during the months of March, April, and May 2020. We also compared these revenues with figures from 2017, 2018, and 2019, to quantify potential losses in hotel revenues. Table 4, Table 5 present these findings.

Table 4.

Hotel room revenues: All U.S. hotels and by hotel operational structure.

| Date | March | Δ | April | Δ | May | Δ | Total 3 months | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel 1 U.S. Hotels (Total) | ||||||||

| 2017 | 13,731,348,565 | 12,922,807,433 | 13,682,957,486 | 40,337,113,484 | ||||

| 2018 | 14,467,946,268 | 5.4% | 13,799,136,738 | 6.8% | 14,400,259,707 | 5.2% | 42,667,342,713 | 5.8% |

| 2019 | 14,752,968,978 | 2.0% | 14,247,532,797 | 3.2% | 14,945,276,259 | 3.8% | 43,945,778,034 | 3.0% |

| 2020 | 7,290,803,160 | −50.6% | 2,533,490,422 | −82.2% | 3,995,028,655 | −73.3% | 13,819,322,237 | −68.6% |

| Panel 2 Chain managed | ||||||||

| 2017 | 3,422,115,380 | 3,205,907,931 | 3,259,197,115 | 9,887,220,426 | ||||

| 2018 | 3,625,850,081 | 6.0% | 3,423,750,212 | 6.8% | 3,381,233,710 | 3.7% | 10,430,834,003 | 5.5% |

| 2019 | 3,622,897,107 | −0.1% | 3,446,920,733 | 0.7% | 3,477,239,576 | 2.8% | 10,547,057,416 | 1.1% |

| 2020 | 1,471,584,134 | −59.4% | 319,479,298 | −90.7% | 470,796,675 | −86.5% | 2,261,860,107 | −78.6% |

| Panel 3 Franchise | ||||||||

| 2017 | 6,582,386,319 | 6,283,011,306 | 6,764,808,040 | 19,630,205,665 | ||||

| 2018 | 6,999,766,884 | 6.3% | 6,808,913,402 | 8.4% | 7,178,437,581 | 6.1% | 20,987,117,867 | 6.9% |

| 2019 | 7,256,891,171 | 3.7% | 7,057,965,274 | 3.7% | 7,550,735,402 | 5.2% | 21,865,591,847 | 4.2% |

| 2020 | 3,859,535,526 | −46.8% | 1,520,749,682 | −78.5% | 2,325,883,838 | −69.2% | 7,706,169,046 | −64.8% |

| Panel 4 Independent | ||||||||

| 2017 | 3,726,478,450 | 3,433,673,742 | 3,658,883,024 | 10,819,035,216 | ||||

| 2018 | 3,842,329,300 | 3.1% | 3,566,473,132 | 3.9% | 3,840,588,414 | 5.0% | 11,249,390,846 | 4.0% |

| 2019 | 3,897,877,148 | 1.4% | 3,683,677,532 | 3.3% | 3,988,974,723 | 3.9% | 11,570,529,403 | 2.9% |

| 2020 | 1,959,683,501 | −49.7% | 693,261,442 | −81.2% | 1,198,346,452 | −70.0% | 3,851,291,395 | −66.7% |

Notes: Δ indicates percent changes compared to previous date.

Table 5.

Hotel room revenues: hotel segments.

| Date | March | Δ | April | Δ | May | Δ | Total 3 months | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel 1 Economy-Scale | ||||||||

| 2017 | 889,737,638 | 832,646,348 | 924,578,341 | 2,646,962,327 | ||||

| 2018 | 920,471,412 | 3.5% | 856,351,303 | 2.8% | 939,837,150 | 1.7% | 2,716,659,865 | 2.6% |

| 2019 | 910,443,031 | −1.1% | 853,481,641 | −0.3% | 943,121,048 | 0.3% | 2,707,045,720 | −0.4% |

| 2020 | 661,932,262 | −27.3% | 470,770,797 | −44.8% | 614,565,827 | −34.8% | 1,747,268,886 | −35.5% |

| Panel 2 Midscale | ||||||||

| 2017 | 627,209,477 | 588,066,480 | 655,282,991 | 1,870,558,948 | ||||

| 2018 | 652,539,496 | 4.0% | 623,567,050 | 6.0% | 679,582,352 | 3.7% | 1,955,688,898 | 4.6% |

| 2019 | 664,959,165 | 1.9% | 630,982,498 | 1.2% | 703,266,092 | 3.5% | 1,999,207,755 | 2.2% |

| 2020 | 418,700,562 | −37.0% | 229,482,308 | −63.6% | 334,396,700 | −52.5% | 982,579,570 | −50.9% |

| Panel 3 Upper Midscale | ||||||||

| 2017 | 2,425,812,604 | 2,305,324,571 | 2,492,915,635 | 7,224,052,810 | ||||

| 2018 | 2,583,785,861 | 6.5% | 2,499,308,189 | 8.4% | 2,651,404,116 | 6.4% | 7,734,498,166 | 7.1% |

| 2019 | 2,680,843,909 | 3.8% | 2,577,924,264 | 3.1% | 2,783,309,153 | 5.0% | 8,042,077,326 | 4.0% |

| 2020 | 1,465,949,118 | −45.3% | 567,682,740 | −78.0% | 906,017,120 | −67.4% | 2,939,648,978 | −63.4% |

| Panel 4 Upscale | ||||||||

| 2017 | 2,355,638,276 | 2,265,828,862 | 2,387,531,165 | 7,008,998,303 | ||||

| 2018 | 2,554,061,412 | 8.4% | 2,485,957,652 | 9.7% | 2,572,573,839 | 7.8% | 7,612,592,903 | 8.6% |

| 2019 | 2,648,921,834 | 3.7% | 2,587,740,437 | 4.1% | 2,719,293,094 | 5.7% | 7,955,955,365 | 4.5% |

| 2020 | 1,285,059,338 | −51.5% | 406,668,022 | −84.3% | 614,537,708 | −77.4% | 2,306,265,068 | −71.0% |

| Panel 5 Upper Upscale | ||||||||

| 2017 | 2,737,584,115 | 2,604,402,067 | 2,692,900,340 | 8,034,886,522 | ||||

| 2018 | 2,839,216,341 | 3.7% | 2,795,763,601 | 7.3% | 2,806,640,099 | 4.2% | 8,441,620,041 | 5.1% |

| 2019 | 2,895,554,136 | 2.0% | 2,835,391,482 | 1.4% | 2,905,723,551 | 3.5% | 8,636,669,169 | 2.3% |

| 2020 | 1,112,127,588 | −61.6% | 136,107,524 | −95.2% | 266,214,440 | −90.8% | 1,514,449,552 | −82.5% |

| Panel 6 Luxury Scale | ||||||||

| 2017 | 1,001,971,689 | 920,764,018 | 897,794,047 | 2,820,529,754 | ||||

| 2018 | 1,116,686,956 | 11.4% | 1,008,502,140 | 9.5% | 942,652,506 | 5.0% | 3,067,841,602 | 8.8% |

| 2019 | 1,100,315,940 | −1.5% | 1,033,899,339 | 2.5% | 982,629,129 | 4.2% | 3,116,844,408 | 1.6% |

| 2020 | 391,924,848 | −64.4% | 29,751,980 | −97.1% | 61,130,081 | −93.8% | 482,806,909 | −84.5% |

Notes: Δ indicates percent changes compared to previous date.

The results from Panel 1 of Table 4 shows that total hotel room revenues for the industry decreased by 50.6%, 82.2%, and 73.3% in March, April, and May 2020 respectively. Year over year, hotel room revenues between March 1 and May 31 had increased by 5.8% and 3.0%, in 2018 and 2019. Assuming that hotel room revenues stayed at the same level as 2019, total revenues would have been about $43.9 billion between March 1 and May 31, 2020. However, due to COVID-19, the cumulative decline in revenues during these 3 months was 68.6% compared to the same period last year (i.e., 2019). Thus, the potential hotel room revenue lost by the U.S. hotel industry is equivalent to the difference between revenues generated between March 1 and May 31 in 2019 and 2020, which is approximately $30 billion.

We also examined the financial impact of COVID-19 on hotels with different operational structures. Panels 2, 3, and 4 of Table 4 present these findings. The results showed that hotel revenues decreased the most for chain-managed hotels with 78.60% decline vs. 64.8% and 66.7% decreases in franchise and independent hotels compared to the same period last year. That is, chain-managed hotels appear to be the most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic during March 1 and May 31, 2020 period.

Additionally, the financial impact of COVID-19 on hotel segments is presented in Table 5. Results show that luxury-scale and upper upscale hotels experienced the largest decline in room revenues between March 1 and May 31, 2020, at 84.5% and 82.5%, respectively, while the decrease in hotel room revenues in upscale, upper midscale, midscale and economy segments were 71%, 63.4%, 50.9% and 35.5%, respectively. These results are consistent (inversely related) with the decline in key hotel performance measures for these hotel segments, presented in the Section 4.2. This translates to a revenue loss of about $1, $1.1, $5.1, $5.6, $7.1 and $2.6 billion for the economy, midscale, upper midscale, upscale, upper upscale, and luxury-scale hotel segments respectively, between 2020 and 2019.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The novel coronavirus, or COVID-19 pandemic has had a disruptive impact across the globe in a relatively short period of time. In particular, the central policy response of limiting or strictly eliminating domestic, inter-state and international travel to contain the spread of the coronavirus has had a severe negative impact on the hotel industry. Thus, analyzing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the U.S. hotel industry in general and across hotel segments and hotel operational structures is of paramount importance. Our study fills an important gap in the formative knowledge on the effects of this rapidly evolving pandemic.

Our results show that the negative effects of COVID-19 on the U.S. hotel industry begun to materialize in early March 2020 and reached their peak on April 11. At this peak, hotel room OCC, ADR and RevPAR were approximately 74%, 47% and 86% lower than the same date last year. While the industry has started to slowly recover from this precipitous drop, RevPAR was still down by 62% on May 31, 2020 compared to same date last year. The results also show that the impact of COVID-19 is not uniform across hotel segments. Economy hotels appear to be the least affected by the pandemic, followed by midscale, upper midscale, and upscale hotel segments, with an average 33.6%, 49.5%, 62.7%, and 69.9% decreases in RevPAR during the study period. However, hotels that are at the higher end of the spectrum—upper upscale and luxury segments—experienced an average 80.3% and 80.7% RevPAR declines. The relatively better resilience of the hotels at the lower-end of the spectrum—economy to upper midscale— to the adversities of the COVID-19 can be explained in many ways. First, hotels in these segments are more likely to be used for self-quarantine and healthcare uses (i.e., use as makeshift medical facilities, as captured in AH&LA's Hospitality for Hope Initiative), and serve markets such as healthcare professionals, emergency responders, and truckers, while extended stay hotels within these segments have a strong existing customer base that keeps performance strong, even during the pandemic (Sperance, 2020a; Wroten, 2020). Second, brands at the lower end of the spectrum have found inventive ways to maintain their OCC, such as Red Roof Inn's “Work Under Our Roof” $29 (day) rates targeting remote workers who need a comfortable and quiet space away from the distractions of working at home (Cision PR Newswire, 2020). Moreover, lower-segment hotels are relatively cost-effective, and requiring fewer employees owing to lower levels of service allows them to offer such discounted rates while maintaining operational feasibility. Thus, they have remained more resilient to hardships of the pandemic, continued their operations more successfully and attained better performance indicators than the upper segment hotels.

On the other hand, higher-end hotels are typically unable to reduce rates beyond a certain threshold (which would spur OCC) owing to their desire to maintain a premium brand image. Moreover, these hotels typically require a higher number of employees to operate their facilities, and have higher operational costs generally, thus making the decision to shut down operations completely a more viable financial option. This outcome likely explains the higher rate of hotel (temporary) closures in the upper upscale and luxury segments, as captured in their decline in room supply during the study period (33% and 58% respectively).

We also found significant differences in the impact of COVID-19 on hotels with different operational structures. Chain-managed hotels were the most affected by the pandemic than were franchise and independent hotels. They experienced an average 75.3% RevPAR decline during the study period, while RevPAR for franchise and independent hotels decreased approximately 63.6% and 63.9% respectively. While differences in other performance measures were similar in magnitude, the room supply of chain-managed hotels experienced a larger decline, at 19%, vs. the 1.9% and 7.9% decline for franchise and independent hotels, respectively on average between March 1, 2020 and May 31, 2020. A likely explanation for these results may be that the majority of chain-managed hotels are likely to fall in the upper upscale and luxury segments—since hotel companies will typically not separate their brand from their management services for such hotels, and thus manage these hotels themselves to ensure brand integrity (for example, Four Seasons or Park Hyatt) (de Roos, 2011). Thus, as explained above, the higher operational costs for these higher-end hotels combined with lower leisure and business demand for the higher-end product, likely resulted in a stronger depression of RevPAR and a higher rate of hotel closure as reflected in the decline in room supply.

Interestingly, while one may readily assume that independent hotels are more vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic, since they do not possess the resources and infrastructure support of a larger hotel company as do chain-managed or franchised properties, they appear to be as resilient as franchise hotels and more resilient than chain-managed hotels. Independent hotels have local owners and operators who can be more flexible in adopting to changing customer needs and operational requirements from the COVID-19 pandemic (McCracken, 2020), and have higher control on issues like pricing, which allows them to take inventive steps such as participate in a treasury-bond style program that allows customers to get a higher face value than its purchase price (Rackl, 2020). Moreover, while lacking the support of a big hotel company, independent hotel coalitions such as the Boutique Lifestyle Leaders Association (BLLA) have launched campaigns that provide independent owners with resources to rebuild and succeed during the coronavirus economic recovery, such as seminars on revenue management, talent acquisition and legal guidelines (Sperance, 2020b). While in previous crises, such as the 2008 downturn, independent operators were quicker to permanently shut down since they felt that it wasn't worth waiting for a recovery while bigger brands rode out of the downturn, more central government support and higher lender assistance and flexibility (lenders are hesitating to take over so many hotels due to a lack of alternative use) appears to be keeping more independent operators afloat and relatively successful during the coronavirus pandemic (Sperance, 2020c).

We also quantified the magnitude of the financial impact of COVID-19 on the U.S. hotel industry overall and across hotel segments and operational structures. The findings showed that the U.S. hotel industry's revenue losses for the critical period of March 1 to May 31, 2020 accumulate to approximately $30 billion. The loss in revenue across hotel segments and operational structures was consistent with our findings pertaining to the decline in key performance measures—OCC, ADR, and RevPAR, among others—highlighting greater negative effects on chain-managed hotels and those at the higher end of the spectrum (luxury and upper upscale). Considering the importance of the hotel industry to the U.S. economy and the significance of the financial impact of COVID-19 on hotel room revenues, the findings of our study have important implications for industry practitioners, policy-makers, destinations, and researchers.

5.1. Practical implications

The hotel industry enjoyed nearly a decade of growth in key performance metrics before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, hotel owners will now face rising operational costs, particularly those to do with new coronavirus cleaning standards. With global brands like Hilton forming partnerships with product suppliers (e.g., Lysol) and healthcare institutions (e.g., Mayo Clinic), and even independent hotels having to heighten cleaning and safety standards, it is estimated that the new cleaning protocols could collectively cost the hotel industry as much as $9 billion each year (Sperance, 2020f). Hotels—chain-managed, franchise, and independent—and those across hotel segments will have to rethink the traditional financial model underlying hotel performance—both from a revenue and cost perspective. They may have to place a greater emphasis on growing occupancy to recover RevPAR, given that their pricing power has been decimated by the drying up of leisure and business travelers (Sperance, 2020d). Limited and select-service hotels may be able to trim some labor costs (particularly, front of the house) increasing the deployment of technology (e.g., digital kiosks/keys for check-in) (Sperance, 2020f) along with “new operational roles” at the unit level and with technologically enhanced systems adhering to safety, distancing, and sanitation guidelines (e.g., no-contact check in/outs) (Kim & Kizildag, 2011). Moreover, hotels across various segments may be required to carry a working capital that suffices for 6 months depending on their operational structures. Hence, lodging establishments, especially parented by multinational large corporations, should fully draw down company's entire credit facility resulting in quantitative easing on their balance sheet (e.g., reducing capital expenditures, halting capital investments, etc.).

In addition to determining ways to operating profitability in an economically-constrained environment, hotels across segments will have to offer a stronger value proposition than Airbnb and other home-sharing options (Dogru, Mody, & Suess, 2019). While hotels can tout a superior value proposition of professionally-cleaned rooms and public spaces and technology options that minimize human interaction, Airbnb has also renewed its focus on its homes business, including enhanced cleaning protocols for hosts (Schaal, 2020). In particular, given that the drive market—typically customers within a 200-mile radius—is likely to lead recovery for accommodation businesses, hotels must re-initiate marketing spending and target their campaigns to fuel demand for “local travel”, as reflected in Airbnb's Go Near initiative (Jelski, 2020). Discounts might be creatively packaged, by bundling services into customized packages and promotions (e.g., upgrades, free meals, airport pickup). This should be done without adding substantially to the property's cost while leveraging the property's exclusive characteristics to remain competitive. In this regard, independent hotels in particular may benefit from new tools offered by digital ad providers such as Google Hotel Ads that enable them to source more bookings from brand-direct distribution channels than from the more-expensive online travel agents (McCracken, 2020; O'Neill, 2020b).

Global hotel companies (like Marriott, Hilton, Wyndham, among others) are anticipating a higher number of brand conversations to come out of the pandemic, expecting independent hotels to join their ranks in order to benefit from these companies' strong brand images, standardized processes (including hygiene and cleaning protocols), and greater marketing and distribution synergies (Sperance, 2020e). However, our results which indicate that independent hotels are more resilient to the economic impact of COVID-19, when combined with the added renovation costs and/or fees associated with being part of a global chain's brand (soft brand or regular) (Sperance, 2020b), and the hotel market's general “softness” for the foreseeable future, suggest that it may not be worth an independent operators' while to opt for a brand conversion. Independent operators may be better off continuing to operate as they are, or consider next-gen management startups that don't require a costly rebrand. On the other hand, the big global brands—chain-managed and franchise hotels—may be able to leverage their (arguably) superior cleaning and hygiene standards to win back customer trust faster than independent hotels (O'Neill, 2020a).

As this study shows the immediate economic impact of Covid-19 on the hotel industry is substantial, and hotel companies exert a tremendous effort to weather these unprecedented challenges and alleviate the abrupt economic damage on their operations. Yet, more importantly, such impactful crises often lead to dramatic changes in consumer patterns and force companies to work with new business paradigms to satisfy changing consumer behavior and demand patterns (Papatheodorou, Roselló, & Honggen, 2010). Anxiety and fear of infection are reshaping the travel and leisure attitude of consumers and will undoubtfully have implications for companies serving in these industries. For instance, in a recent study, Kock, Norfelt, Josiassen, Assaf, and Tsionas (2020) have documented that perceived infectability to Covid-19 increases travelers' propensity to travel in groups, book travel insurance and remain loyal to previously visited destinations. The study has also revealed that perceived risk of infection makes travelers more concerned about crowding and creates an urge of being contained in their inner circle. Therefore, it is utmost important for service companies including hotel operators to respond to changing customer perceptions, preferences and needs in order enhance their resilience and ability survive. Flexibility and agility will be key words for hotel operators in the years ahead. With the new norms in the post-pandemic era, hotels will be in need of restoring customer confidence through customer-centric and innovative solutions such as more flexed booking and cancellation policies, enriched loyalty programs, differentiated hotel amenities, increased used of robotics to enhance contactless service, and extra attention to hygiene at hotel stays. Even now, hotel customers' preferences are changing in favor of robot services compared to human services due to the ability of offering contactless service, which helps maintain social distancing and reducing anxiety of contagion through human interaction (Kim, Kim, Badu-Baiden, Giroux, & Choi, 2021).

Operating uncertainties of the future, coupled with significant revenue loss during the pandemic, worsen the prospects of the hotel industry in terms of profitability and survivability. While these will be pivotal operating and financial challenges for hotel operators in the upcoming years, another major obstacle for the industry will be the lack of access to a quality workforce. Even in the pre-pandemic world, hotel jobs have been losing their attraction due to irregular and/or seasonal working patterns (Lee & Way, 2010), relatively low pay (Wan, Wong, & Kong, 2014) and transitory nature of the hotel jobs. The necessity of the hotel companies to put many of their employees on furlough or laying them off entirely during the pandemic added to the concerns of job insecurity in the hotel industry while underlining the vulnerability of hotel jobs to external shocks (Sogno, 2020). Coupled with already existing, pre-pandemic challenges to attract talent, hotel operators will experience a major hardship to lure talent to hotel jobs. In accordance with this view, Filimonau, Derqui, and Matute (2020) further underlines the importance of strengthening organizational resilience and investment in corporate social responsibility in retaining talented work-force, particularly senior managers with valuable skills sets, who can easily find employment in other sectors of the economy.

For policy makers, our research quantifies the magnitude of the economic losses to the hotel industry, which has significant implications for issues ranging from financial aid to employment, taxation, and public health policy. First, our research demonstrates that hotels of all sizes (segments and operational structures) appear to have suffered significantly; thus, financial aid should not be restricted to small businesses and the manner in which it is executed may be improved. In particular, employees in the accommodation industry are highly vulnerable—both in terms of being subject to furlough, layoffs, or being unable to work as a result of social distancing, and having among the lowest annual earnings and the lowest levels of education of all sectors. The pandemic may further serve to reinforce already substantial disparities in income, thus highlighting the need for better social welfare and job security that is reinforced via the guidelines for financial aid to the hospitality industry (Gössling et al., 2020). In this regard, the larger higher-tier hotels that create more jobs and independent hotels without the financial backing of large companies should likely be prioritized in financial aid programs. Second, the both federal and state governments may stimulate the demand-side recovery of the hospitality industry by offering travel tax credits as part of stimulus payments, thus incentivizing citizens to travel sooner and more often. Relatedly, tax deferrals—including payroll tax deferrals—for the hardest-hit industries like hospitality may allow hotels to maintain the levels of cash flow needed to survive the pandemic (Stein, Siegel, Long, & Werner, 2020). Taking advantage of tax deferrals for labor might most likely help continue cost saving measures (e.g., deferring the payment of the employer share of FICA taxes of 6.2%) even when demand is back to normal to recover the losses during the crisis. Third, for destinations, the lack of business for hotels translates to a significant reduction in tax revenues. In this regard, our findings point to the need for a diverse portfolio of hotel segments within a destination. While economy hotels may not generate as large a tax receipt or levels of employment as larger, full-service hotels, this segment appears to be more resilient and thus continues to provide tax revenues during a pandemic. Midscale hotels are also relatively stronger, and in addition to potentially higher tax revenues than an economy hotel, they also tend to employ more people, and have a higher impact on the overall economy (Dogru, McGinley, & Kim, 2020).

Furthermore, while many hotels are being re-positioned for healthcare and social service functions, as evidenced by Hospitality for Hope initiative, federal and state governments can use this as an opportunity to collaborate with hotels, healthcare institutions, and public policy organizations to develop public health infrastructure for future pandemics by creating policy that encapsulates guidelines for hotel-to-hospital conversions and reimbursement via national health insurance programs, among other issues. Again, the larger, higher-tier hotels and independent hotels may be well-suited to benefit from such programs. In addition to the tax revenues, hotel establishments should focus on ancillary revenues that maybe generated through non-core revenue generating areas such as gyms, spas, laundry services, etc. Perhaps, hotels might need to provide services that have traditionally not been part of the hotel's core offerings such as food delivery through online platforms or leasing of kitchens for cloud kitchen requirements until the adverse effects of COVID-19 is over. Thus, destinations should incentivize the creation of a diverse hotel infrastructure that attracts different types of customers and allow hoteliers to use infrastructure to capitalize on ancillary revenues, subsequently enabling the destination to better withstand an economic shock such as a pandemic. Above-mentioned solutions should be rolled out as part of recovery plan to revamp the occupancy levels, and thus the ADR and RevPAR.

5.2. Theoretical implications

The pandemic has already changed the ways hotels operate globally: new policies, frameworks, strategies, and plans to mitigate risk; echoing the “new normal” suggested by chaos theory. Adhering to the premises of the chaos theory, examining key strategies and blueprints that promote financial recovery, financial resilience, and economic prosperity for a durable financial and operational bounce back is critical. Within this domain, we tried to connect the dots using the context of the chaos theory with our results to demonstrate how executives might mitigate damage to the financial shocks of COVID-19. We have tied our results mostly on the sensitive dependence on initial conditions as a small change in a state of a deterministic condition/event/aggressor that can result in positive financial evaluation in a later state (Werndl, 2009). To put it differently, our implications are aligned with the main postulations of the chaos theory that small bundles of initial recovery strategies most likely lead to healthier financial and operational revamps of lodging establishments' financial, and especially operational assessment and outcomes for restoring the essential cores of lodging businesses over the long-haul. Within the primary underpinnings of the chaos theory, financial and operational recovery plans can be very well characterized according to the several elements in complex network relationships that occur in a dynamic manner with constant changes and further financial stimuli from governments (Boukas & Ziakas, 2014; McKercher, 1999). In so doing, a kick-off point would be the step-by-step contingency plans and recovery blueprints to small and low probability events that have the potential to result in major harmful impacts threatening to the organization's status quo. Overall, as the chaos theory suggests, the whole context of lodging organizations' primary operational strategies and practices should be examined as a non-linear, non-deterministic operating system, unlike most firms' traditional operational hierarchies.

5.3. Limitation and recommendation for future research

There are some limitations to our study, which also provide opportunities for future research. First, while based on a comprehensive dataset that parallels the critical timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic, the study is largely descriptive in nature, with limited inferences about the specific causes or effects of the decline in hotel performance. Second, our analysis and calculations are limited to the STR dataset, which, while being the most comprehensive in this domain, consists of about 74% of the properties in the U.S. hotel census in terms of room counts. Third, our analysis was conducted for the U.S. overall. There may be significant differences across states that must be investigated in future research. Relatedly, researchers must examine the impact of the pandemic on hotels in different countries, since their segments and operational structures may be different (e.g., global brands across segments are typically managed by the hotel companies themselves in India and China) and differently impacted than in the U.S. Fourth, the economic impact analysis in this study is limited to hotel industry's revenues only. However, there are other related economic impacts that tied to the loss in hotel revenues, such as the loss of jobs and tax revenues, and a general decrease in joint demand (e.g., a traveler eating a meal at a restaurant) and lower multiplier effects. These must be investigated in future research. Finally, while our research demonstrates large, negative effects on all segments and operationalize structures, the extent to which hotels lost demand to Airbnb and other home-sharing providers, and the how the pandemic is likely to impact customers' decisions to choose an accommodation (hotels vs. home-sharing) will provide further indications of a more complete current and expected economic impact of COVID-19 on the hotel industry.

Contributions

Ozgur Ozdemir: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal Analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Writing- original draft; Writing- review & editing.

Tarik Dogru: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Formal Analysis; Writing- original draft; Writing- review & editing.

Murat Kizildag: Conceptualization; Writing- original draft; Writing- review & editing.

Makarand Mody: Writing- original draft; Writing- review & editing.

Courtney Suess: Writing- original draft; Writing- review & editing.

Biographies

Ozgur Ozdemir is an assistant professor in the William F. Harrah College of Hospitality at University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He obtained his Ph.D in Hospitality Management with a concentration in financial management from the Pennsylvania State University. Dr. Ozdemir's main research areas include corporate finance, capital markets, agency issues, initial public offerings (IPOs), and corporate governance in the hospitality industry. His work has been published in hospitality, tourism and business journals including Tourism Management, International Journal of Hospitality Management, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, Hospitality Financial Management, and International Business Review.

Tarik Dogru is an assistant professor of hospitality management in the Dedman School of Hospitality at Florida State University. He earned a bachelor's and master's degree in business administration from Zonguldak Karaelmas University and earned a doctorate degree in hospitality management from University of South Carolina. Prior to joining Florida State

University, Dr. Dogru worked at Boston University as an assistant professor for 2 years. His research interests include sharing economy, corporate finance, franchising, hotel investments, tourism economics, climate change, and blockchain technology.

Murat Kizildag joined UCF's Rosen College as an assistant professor in August 2013. Before joining UCF, Dr. Kizildag held an instructor of managerial finance position at Texas Tech University. Prior to his Ph.D. in Hospitality Administration with a concentration in Finance, Dr. Kizildag received his MBA with an emphasis in finance and his M.S. in Restaurant, Hotel, and Institutional Management from Texas Tech University. Dr. Kizildag is intrigued by the depth of financial research. His research expertise span the areas of Security Valuation, Risk & Investment Analytics, Financial Modeling & Forecasting, Portfolio Management & Optimization, and Time-Series Analysis. Dr. Kizildag teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in financial management, managerial accounting, and financial analysis for hospitality enterprises. Dr. Kizildag sits on several editorial and advisory boards of top-tier international academic journals, conferences, and organizations. He is also the Coordinating Editor overseeing finance and economic papers in one of the leading SSCI journals, the International Journal of Hospitality Management (IJHM).

Makarand Mody is an Assistant Professor of Hospitality Marketing at Boston University's School of Hospitality Administration. Dr. Mody graduated with his Ph.D. from Purdue University. He received his M.Sc in Human Resource Management for Tourism and Hospitality from the University of Strathclyde, and a Higher Diploma in Hospitality Management from IMI University Centre, Switzerland. Dr. Mody has worked in the hotel and airlines industries in the areas of learning and development and quality control. His research focuses on issues pertaining to the supply and demand of responsible tourism, the sharing economy, and the modeling of consumer behavioral pathways.

Courtney Suess is an Assistant Professor at Texas A & M University in the department of Recreation, Parks and Tourism Sciences. Administration, she holds a Bachelor's Degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a masters and Ph.D. from UNLV's William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration.

References

- AHLA COVID-19 Devastating hotel industry. 2020. https://www.ahla.com/sites/default/files/FACT%20SHEET_COVID19%20Impact%20on%20Hotel%20Industry_4.22.20_updated.pdf Retrieved from.

- Airlines for America Impact of COVID-19: Data updates. 2020. https://www.airlines.org/dataset/impact-of-covid19-data-updates/ Retrieved from.

- Arana J.E., León C.J. The impact of terrorism on tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research. 2008;35(2):299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Boukas N., Ziakas V. A chaos theory perspective of destination crisis and sustainable tourism development in islands: The case of Cyprus. Tourism Planning & Development. 2014;11(2):191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Campiranon K., Scott N. Critical success factors for crisis recovery management: A case study of Phuket hotels. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2014;31(3):313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Chan E.S., Lam D. Hotel safety and security systems: Bridging the gap between managers and guests. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2013;32:202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cision PR Newswire Red Roof® offers “work under our roof” day rate to provide a comfortable and quiet space for remote workers. 2020. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/red-roof-offers-work-under-our-roof-day-rate-to-provide-a-comfortable-and-quiet-space-for-remote-workers-301031912.html Retrieved from.

- Dixon V. By the numbers: COVID-19's devastating effect on the restaurant industry. 2020. https://www.eater.com/2020/3/24/21184301/restaurant-industry-data-impact-covid-19-coronavirus Retrieved from.

- Dogru T., McGinley S., Kim W.G. The effect of hotel investments on employment in the tourism, leisure and hospitality industries. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2020;32(5):1941–1955. [Google Scholar]

- Dogru T., Mody M., Suess C. Adding evidence to the debate: Quantifying Airbnb’s disruptive impact on ten key hotel markets. Tourism Management. 2019;72:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Drakos K., Kutan A.M. Regional effects of terrorism on tourism in three Mediterranean countries. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2003;47(5):621–641. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner B., Vikulov L. Katherine, washed out one day, back on track the next: A post-mortem of a tourism disaster. Tourism Management. 2001;22(4):331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Filimonau V., Derqui B., Matute J. The COVID-19 pandemic and organizational commitment of senior managers. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2020;21:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleick J. The Penguin Group; New York: 2008. Chaos: Making a new science. New York: The Penguin Group. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich J.N. September 11, 2001 attack on America: A record of the immediate impacts and reactions in the USA travel and tourism industry. Tourism Management. 2002;23(6):573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M. Crisis event in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism. 2010;13(5):401–417. [Google Scholar]

- Hospitalitynet China hotel performance recovered quickly following SARS. 2020. https://www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4097010.html Retrieved from.

- Jelski C. Airbnb increases focus on local travel. Travel Weekly. 2020 https://www.travelweekly.com/Travel-News/Hotel-News/Airbnb-increases-focus-on-local-travel Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Kizildag M. M-learning: Next generation hotel training system. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology. 2011;2(1):6–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Kim J., Badu-Baiden F., Giroux M., Choi Y. Preference for robot service or human service in hotels? Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021;93:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizildag M. Financial leverage phenomenon in hospitality industry sub-sector portfolios. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2015;27(8):1949–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kizildag M., Ozdemir O. Underlying factors of ups and downs in financial leverage overtime. Tourism Economics. 2017;23(6):1321–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Kock F., Norfelt A., Josiassen A., Assaf A.G., Tsionas M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The Evolutionary Tourism Paradigm. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020;85:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosova R., Enz C.A. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the financial crisis of 2008: The impact of external shocks on U.S. hotel performance. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. 2012;53(4):308–325. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo H.I., Chen C.C., Tseng W.C., Ju L.F., Huang B.W. Assessing impacts of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tourism Management. 2008;29(5):917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws E., Prideaux B., Chon K. In: Crisis Management in Tourism. Laws E., Prideaux B., Chon K., editors. CABI; Wallingford: 2007. Crisis management in tourism: Challenges for managers and researchers. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Way K. Individual employment characteristics of hotel employees that play a role in employee satisfaction and work retention. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2010;29(3):344–353. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin R. Phoenix; London: 1993. Complexity: Life on the edge of chaos. [Google Scholar]

- Lix L.M., Keselman J.C., Keselman H.J. Consequences of assumption violations revisited: A quantitative review of alternatives to the one-way analysis of variance F test. Review of Educational Research. 1996;66(4):579–619. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz E. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 1972. Predictability. Does the flap of a butterfly wing in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas? [Google Scholar]

- Mair J., Ritchie B.W., Walters G. Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Current Issues in Tourism. 2016;19(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken S. How the COVID-19 crisis could change independent hotels. 2020. https://www.hotelnewsnow.com/Articles/303252/How-the-COVID-19-crisis-could-change-independent-hotels Retrieved from.

- McKercher B. A chaos approach to tourism. Tourism Management. 1999;20(4):425–434. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher B., Chon K. The over-reaction to SARS and the collapse of Asian tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2004;31(3):716–719. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P. Chaos theory as a model for managing issues and crises. Public Relations Review. 1996:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- National Restaurant Association Restaurant sales fell to their lowest real level in over 35 years. 2020. https://restaurant.org/articles/news/restaurant-sales-fell-to-lowest-level-in-35-years Retrieved from.

- Novelli M., Burgess L.G., Jones A., Ritchie B.W. No Ebola… still doomed’–The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research. 2018;70:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill S. Coronavirus upheaval prompts independent hotels to look at management company startups. Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/05/11/coronavirus-upheaval-prompts-independent-hotels-to-look-at-management-company-startups/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill S. Pandemic prompts indie hotels to buy ads in price-comparison searches. Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/06/16/smaller-hotels-companies-find-new-reasons-to-buy-ads-in-price-comparison-search-google-hotel-ads-independent-hotels/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodorou A., Roselló J., Honggen X. Global economic crisis and tourism: Consequences and perspectives. Journal of Travel Research. 2010;49(1):39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam A. A comprehensive approach to classifying acts of crime and violence at tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research. 1999;38(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rackl L. Pay now, stay later: Hotels hit hard by coronavirus pandemic selling “bonds” for future travel. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavirus/ct-coronavirus-hotel-bonds-future-travel-0417-20200420-gjkxphrbvvcljm3uzjndnsxoca-story.html. Chicago Tribune. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Rivera M., Kizildag M., Croes R. Covid-19 and small lodging establishments: A break-even calibration analysis (CBA) model. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021;94:102814. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roos J. Gaining maximum benefit from franchise agreements, management contracts, and leases. 2011. https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/309/ Retrieved from.

- Schaal D. Airbnb CEO tells hosts success against hotel competitors hinges on adopting cleaning protocols. Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/05/13/airbnb-ceo-tells-hosts-success-against-hotel-competitors-hinges-on-adopting-cleaning-protocols/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Sogno A. COVID-19 crisis forces hoteliers to review their human resources strategies. HospitalityNet. 2020 https://www.hospitalitynet.org/opinion/4098660.html Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Sorells M. Data shows severe impact of coronavirus on global hospitality industry. 2020. https://www.phocuswire.com/str-global-hotel-data-march-21-coronavirus Retrieved from.

- Sperance C. 15,000 U.S. hotels offer rooms for coronavirus emergency services. Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/04/01/15000-u-s-hotels-offer-rooms-for-coronavirus-emergency-services/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Sperance C. Boutique hotels push back on major chain brand conversion tactics. Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/05/28/boutique-hotels-push-back-on-major-chain-brand-conversion-tactics/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Sperance C. Global hotels will lose just 2 percent of supply permanently because of coronavirus: Report. Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/05/06/global-hotels-will-lose-just-2-percent-of-supply-permanently-because-of-coronavirus-report/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Sperance C. Has coronavirus upended the hotel industry’s main performance metric? Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/04/20/has-coronavirus-upended-the-hotel-industrys-main-performance-metric/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Sperance C. Hotels are betting big on brand conversions coming of out of the crisis: Is that smart? Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/05/14/hotels-are-betting-big-on-brand-conversions-coming-of-out-of-the-crisis-is-that-smart/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Sperance C. Hotels could face $9 billion in new costs to stay squeaky clean. Skift. 2020 https://skift.com/2020/06/24/hotels-could-face-9-billion-in-new-costs-to-stay-squeaky-clean/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Stein J., Siegel R., Long H., Werner E. Airlines, travel and cruise industries hurt by coronavirus could get tax relief from White House. The Washington Post. 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/03/06/white-house-could-seek-timely-targeted-aid-us-industries-hurt-by-coronavirus-outbreak-top-adviser-says/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . 2020. International tourist arrivals could fall by 20-30% in 2020. Retrieved from https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-arrivals-could-fall-in-2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y.K., Wong I.A., Kong W.H. Student career prospect and industry commitment: The roles of industry attitude, perceived social status, and salary expectations. Tourism Management. 2014;40:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Werndl C. What are the new implications of chaos for unpredictability? The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 2009;60(1):195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Williams G.P. Joseph Henry Press; Washington, D.C: 1997. Chaos theory tamed. [Google Scholar]

- Wroten B. Extended-stay hotels poised to weather drop in travel. 2020. https://www.hotelnewsnow.com/Articles/301360/Extended-stay-hotels-poised-to-weather-drop-in-travel Retrieved from.