Abstract

Background

Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is common. Identification of the exacerbating factors could facilitate interventions for forecastable environmental factors through adjustment of the patient’s daily routine. We assessed the effect of natural environmental factors on the exacerbation of IBD.

Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, studies published from January 1, 1992 to November 3th, 2022 were searched in the MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL Complete and Cochrane Library databases. We extracted data related to the impact of environmental variations on IBD exacerbation, and performed a meta-analysis of the individual studies’ correlation coefficient χ2 converted into Cramér’s V (φc) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

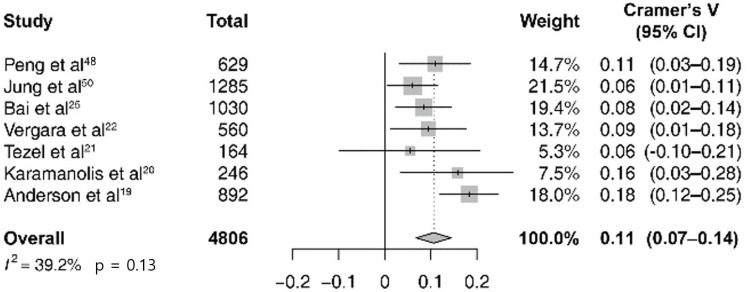

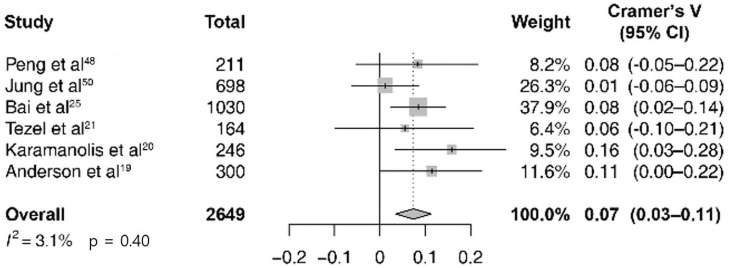

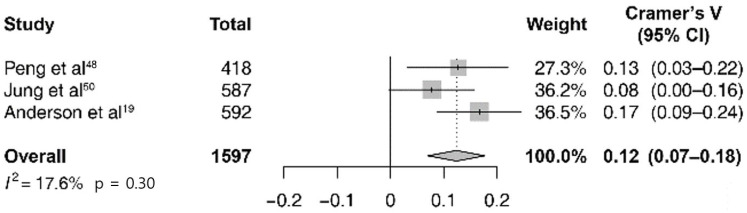

A total of 7,346 publications were searched, and 20 studies (sample size 248–84,000 cases) were selected. A meta-analysis with seven studies was performed, and the pooled estimate of the correlation (φc) between the seasonal variations and IBD exacerbations among 4806 cases of IBD exacerbation was 0.11 (95% CI 0.07–0.14; I2 = 39%; p = 0.13). When divided into subtypes of IBD, the pooled estimate of φc in ulcerative colitis (six studies, n = 2649) was 0.07 (95% CI 0.03–0.11; I2 = 3%; p = 0.40) and in Crohn’s disease (three studies, n = 1597) was 0.12 (95% CI 0.07–0.18; I2 = 18%; p = 0.30).

Conclusion

There was a significant correlation between IBD exacerbation and seasonal variations, however, it was difficult to synthesize pooled results of other environmental indicators due to the small number of studies and the various types of reported outcome measures. For clinical implications, additional evidence through well-designed follow-up studies is needed.

Protocol registration number (PROSPERO)

CRD42022304916.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract [1] that has an increasing global prevalence [2]. Following an IBD diagnosis, 1 in 4 patients are hospitalized owing to exacerbation [3]; thus, IBD affects the quality of life of patients [4]. Exacerbation of IBD is related to microbiological, immunological, and environmental factors [5]. Several interventional attempts targeting genetic, microbiological and immunological factors have been undertaken; however, there is no clear evidence that the interventions can alter the exacerbation of IBD [6–9]. Although interventions for environmental factors are limited, they have the advantage of easily inducing changes in the patient’s health behavior depending on the environment and are therefore more cost-effective and could possibly prevent exacerbation without adverse effects.

Studies claiming to show a relationship between the onset of symptoms in established IBD and seasonal variation began to be published in the 1970s [10, 11]. With increasing research on the activity of IBD [12], studies on the relationship between IBD exacerbation and seasonal variations have been published [13]. However, a follow-up study reported that the correlation between IBD exacerbation and seasonal variation was insignificant [14]. In contrast, a large-scale cohort study in Sweden showed a significant correlation of the onset of IBD symptoms with the season or month of birth [15, 16]. Thereafter, some case-series showed that exacerbation was significantly related to a specific month in pediatric or adult UC patients [17], although subsequent studies on IBD exacerbation provided conflicting results [18–27].

A single systematic review of seasonal variation and exacerbation of IBD exists [28], but it is a conference abstract with a different scope because the review did not evaluate temperature and atmosphere besides the seasonal variation. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effect of temperature, weather, seasons, atmosphere, and climate on the exacerbation of IBD.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines [29] and PRISMA checklist presented in the S1 Checklist. The inclusion criteria were as follows: the study should include adult participants diagnosed with IBD who experienced exacerbation; the study should analyze the effects of IBD symptom exacerbation and temperature, weather, season, climate, and atmosphere; studies published in the last 30 years. IBD exacerbation can be defined as the recurrence of symptoms or worsening of the quantified activity index without other secondary causes, or the related medical use such as outpatient visits, hospitalizations or change or increase in IBD medications [30, 31]. Temperature is the quantity of the atmosphere measured with a thermometer, weather refers to the state of the atmosphere, seasons are periods divided by meteorological and climatic features, the atmosphere is the property of gases surrounding the crust, and climate means a change in the weather over a period of more than 30 years [32]. We applied no restriction on the language of publication, and study designs included controlled or observational studies. The exclusion criteria were research on the initial diagnosis of IBD or studies targeting pediatric populations. The pediatric IBD studies were excluded from our review because important factors affecting exacerbation such as nutrition and puberty were different from those of adults [33].

The search was conducted by one author (SJM) using data from the core-databases, MEDLINE, Embase, Cumulative Index Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Complete, and Cochrane Library database on November 3th, 2022. Studies published from January 1st, 1992 to November 3th, 2022 were searched using the publication filter provided by each database. Conference proceedings of the Asia Pacific Digestive Week (APDW) and Australia Gastroenterology Week (AGW), which are not included in the core-database, were manually searched. The search terms included: IBD, “ulcerative colitis” and “Crohn’s disease” and “temperature,” “weather,” “climate” and “atmosphere.” A search query was created using the keyword subjective terms and the truncated form of each term, which were then grouped with the search command. The final search queries were reviewed by the librarian. The entire search results are presented in the S1 Table.

Studies published in foreign languages were translated before review, and for studies where data extraction was difficult owing to the availability of only the abstract, additional data were requested from the respective corresponding authors. Studies with the same author and database name, study area or medical institution name, we contacted corresponding authors to resolving the duplication of sample issue. SJM and HJS performed screening and data extraction independently of each other according to the predefined inclusion criteria. In case of a discrepancy, the same process was repeated until a consensus was reached. Any persistent discrepancies were resolved with the guidance of a third author (KK).

Data analysis

All authors selected the information list of items to be extracted from each individual study well before the commencement of the review, and a predefined unified form was created using Microsoft Excel (Professional Plus edition). Next, two authors (YCL and SJM) independently performed data extraction. In case of any discrepancies, consensus was reached under the guidance of the third author (HJS). The extracted variables could be divided into publication information, patient-related information, environmental factor related information, and outcome related lists. The patient-related information was further subdivided into sociodemographic and disease-related variables. Sociodemographic extraction variables included sex, age, racial ratio, and income level. Geographically, the latitude, longitude, and altitude of the study city and climate group information according to the Köppen climate classification were extracted [34]. With regard to the disease, (IBD)-related extraction variables, the criteria for diagnosis and subtype of IBD (i.e., UC and CD), and anatomical location, activity, and definition of exacerbation in individual studies were extracted. For the sample size extraction, we distinguished between case-based and person-based enumeration of exacerbation. Moreover, the types of environmental factors and databases were extracted. For the extraction of outcome variables, the methods of statistical analysis, index value (i.e., correlation coefficient or odds ratio), significance, and extractable raw data related to IBD exacerbation and environmental change were all extracted. The quality assessment was independently conducted by two authors (SJM and LYC). Furthermore, for the quality assessment, we used the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for cohort and case–control studies [35] and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)’s critical appraisal tools for case-series [36].

A meta-analysis of studies that investigated the relationship between the seasonal variation and the exacerbation of IBD was performed. To facilitate a unified analysis, individual studies were observed and actual exacerbation events were extracted for all the 12 months. The four seasons were defined by the quarterly grouping of months: March–May for spring; June–August for summer; September–November for autumn; and December–February for winter. The seasonal data were obtained from the monthly data and summarized in the contingency tables before conducting the two-tailed chi-square test. Then, the corresponding effect size, Cramér’s V (φc), was converted from the test statistics in each study [37–39]. The pooled estimate and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the effect size were obtained by synthesizing the data from the previous studies. Pooled φc is a non-negligible effect if < 0.057, a non-negligible-to-weak effect if 0.058–0.12, a weak-to-moderate effect if 0.12–0.23, a moderate-to-strong effect if 0.23–0.46, and a strong effect if ≥0.46 [38]. A meta-analysis was performed using the random-effects model [40]. Heterogeneity was calculated as an I2 statistic with a range of 0–100%, where I2 values of 1%–49%, 50%–74%, and >75% indicated low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [41]. In addition, when the number of studies included in the meta-analysis was less than 10, a heterogeneity test was additionally performed with the χ2 square test. If the p-value of this test was less than 0.1, heterogeneity was judged to be significant [42]. Results with <50% heterogeneity were included in [43] further subgroup analyses of the IBD subtype and the climate of the study region. The R metacor package (version 2.1) was used to calculate the pooled estimate of the correlation coefficient with 95% CI and then present the values as forest plots. Publication bias was assessed by drawing funnel plots with odds ratio (OR) after meta-analysis as well as by Egger’s test if more than 10 studies [44]. The review protocol for this research was submitted and registered with the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) prior to study initiation (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42022304916).

Results

A total of 7,346 publications were searched and screened. Of these, 20 studies met the selection criteria and were finally selected for inclusion in the systematic review (Fig 1). In these 20 studies, the sample size ranged from 248 to 84,000 cases. Of the 20 studies, 3 were on air pollution, 2 on temperature, and the remaining 15 were on seasonal variation. Sociodemographic, geographic characteristics, disease, and exposure characteristics from all 20 studies are summarized in S2 and S3 Tables, and the results of quality assessment are presented in S4 and S5 Tables. Among the studies included, 15 investigated the correlation between seasonal variation and the exacerbation of IBD; moreover, 4 out of 15 studies were conference abstracts and the remainder (11 studies) were journal articles. Furthermore, 3 out of 15 studies were cohort studies and 12 were case-series; 6 out of 15 studies were conducted in Europe and 9 in Asia and the Americas and in particular, most of the studies (9 out of 15 studies) were classified as Köppen Climate Classification Group C (temperate climate) research (Table 1). The number of cases ranged from 164 to 76,608; three studies were UC-only studies and 12 studies were IBD patients (Table 1). In 5 out of 15 studies, IBD exacerbation was defined based on the admission or readmission rate, and 6 studies used an assessment tool for evaluating IBD disease activity or to determine whether a treatment drug was prescribed during the IBD exacerbation; however, three studies used the author’s own definition and one study used both admission and disease activity measurement as the criteria for diagnosing exacerbation (Table 1). A meta-analysis was feasible only for seven studies that reported, predicted, and observed event values over 12 months and used the same methods for statistical analysis (Table 1).

Fig 1. Flowchart of the study selection.

Table 1. Key characteristics of seasonal variation studies (n = 15).

| Publication type | Study design | Country (city) | Climate group | IBDa sub-type | n (cases) | Definition of exacerbation | Statistics | Study conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yadav et al. (2019) [45] | Conference abstract | Cohort (retro-prospective) study | Ireland (nationwide) | Group Cd | IBD | 266 | Admission | One-way ANOVAb | NSc |

| Yadav et al. (2019) [46] | Conference abstract | Cohort (retro-prospective) study | Ireland (Dublin) | Group C | IBD | 227 | Admission | Chi-square test | Spring and summer |

| Stein et al. (2016) [47] | Journal | Case-series study | US (nationwide) | Group Ae to Ef | IBD | 76,608 | Admission | Logistic regression | NS |

| Peng et al. (2015) [48] | Journal | Case-series study | China (Shanghai) | Group C | IBD | 629 | Clinical, radiological, endoscopic, and histological features | Chi-square test | Summer |

| Tinsley et al. (2013) [49] | Conference abstract | Cohort (retro-prospective) study | US (nationwide) | Group A to E | IBD | 3360 | Readmission | Odds ratio | Autumn |

| Jung et al. (2013) [50] | Journal | Case-series study | South Korea (Seoul, Gyeonggi) | Group Dg | IBD | 1285 | Symptom or additional drug prescription or admission | Chi-square test | Spring |

| Beaulieu et al. (2009) [26] | Conference abstract | Case-series study | US (Pittsburgh) | Group C | IBD | 651 | Disease activity measurement | ·· | Spring |

| Bai et al. (2009) [25] | Journal | Case-series study | China (Nanchang) | Group C | UCh only | 1030 | Symptom or additional drug prescription | Chi-square test | Spring and summer |

| Soncini et al. (2006) [24] | Journal | Case-series study | Italy (nationwide) | Group Bi to E | IBD | 2856 | Admission or disease activity measurement | Logistic regression | NS |

| Lewis et al. (2004) [23] | Journal | Case-series study | UK (nationwide) | Group C | IBD | 4360 | Additional drug prescription | Logistic regression | NS |

| Vergara et al. (1997) [22] | Journal | Case-series study | Spain (Barcelona) | Group C | IBD | 560 | Disease activity measurement | Chi-square test | Summer |

| Tezel et al. (1997) [21] | Journal | Case-series study | Turkey (Ankara) | Group C | UC only | 164 | Disease activity index and endoscopic index | Chi-square test | NS |

| Karamanolis et al. (1997) [20] | Journal | Case-series study | Greece (Pireaus) | Group B | UC only | 248 | Symptom or laboratory finding (diarrhea, blood and/or pus in stool, etc.) | Chi-square test | Spring and Autumn |

| Anderson et al. (1995) [19] | Journal | Case-series study | Canada (Vancouver) | Group C | IBD | 892 | Symptom assessment by physicians | Chi-square test | Autumn and winter |

| Sonnenberg et al. (1994) [18] | Journal | Case-series study | US (nationwide) | Group A to E | IBD | 28208 | Admission | Time-series analysis | Winter |

aIBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

bANOVA: analysis of variance.

cNS: not significant.

dGroup C: Temperate climate group.

eGroup A: Tropical climate group.

fGroup D: Continental climate group.

gGroup E: Polar climate group.

hUC: ulcerative colitis.

iGroup B: Arid climate group.

Among the 4806 cases of total IBD exacerbation in the abovementioned seven studies, the pooled estimate of the correlation between the expected cases and the actual observed ones was 0.11 (95% CI 0.07–0.14; I2 = 39%; p = 0.13; Fig 2). A subgroup analysis was performed by dividing IBD into the UC and CD subgroups. In six studies, there were 2649 cases of UC exacerbation and in three studies, there were 1597 cases of CD; the pooled estimate of the correlation between the expected cases and the observed cases was 0.07 (95% CI 0.03–0.11; I2 = 3%; p = 0.40; Fig 3) and 0.12 (95% CI 0.07–0.18; I2 = 18%; p = 0.30; Fig 4). In all sub-groups, the heterogeneity test was not significant with a p-value of 0.10 or higher. For subgroup analysis according to the Köppen Climate Classification, we identified five temperate climate (Group C) studies and one dry climate (Group B) and one cold climate (Group D) study. The pooled estimates for 3,275 out of five temperate climates was 0.11 (95% CI 0.07–0.14; I2 = 0%; p = 0.74; S1 Fig), without significant heterogeneity. The publication bias (S2 Fig) and the results of the remaining eight studies that were not included in the meta-analysis (due to the lack of monthly expected and observed values of exacerbation) are not presented.

Fig 2. Forest plot of seasonal variation and inflammatory bowel disease exacerbation studies (n = 7).

Fig 3. Forest plot of seasonal variation and ulcerative colitis exacerbation studies (n = 6).

Fig 4. Forest plot of seasonal variation and Crohn’s disease exacerbation studies (n = 3).

Discussion

Our study included a total of 20 studies on the effects of temperature, weather, season, and atmosphere on the exacerbation of IBD [18–27, 45–54], and a meta-analysis of the correlation between the seasonal variation and IBD exacerbation was performed using seven studies; the results showed a non-negligible to weak correlation [18, 20–22, 25, 48, 50]. In the UC subgroup (six studies), seasonal variation showed a non-negligible to weak correlation, whereas in the CD subgroup (three studies), seasonal variation showed a weak positive correlation with the exacerbation of IBD. In addition, the temperate climates subgroup (five studies) showed a non-negligible to weak, but significant positive correlation. There was a low level of heterogeneity between the studies in both overall and subgroup analyses. Although the meta-analysis of three studies on air pollution was not performed [27, 51, 52], all three of the studies reported a significant positive correlation between air pollutants and exacerbation of IBD.

When examining the studies that were not included in the meta-analysis, it seems that IBD exacerbation tended to occur slightly more frequently in warmer seasons. First, among the ten studies that reported a significant correlation between seasonal variation and IBD exacerbation, six reported a significant correlation with spring or summer [22, 25, 26, 46, 48, 50], and the remaining three reported a correlation with winter or autumn [18, 19, 49]; in one study, both spring and autumn were reported (Table 1) [20]. Second, two studies that reported the relationship between short-term extreme temperature change and IBD exacerbation support our hypothesis that warmer seasons were associated with more IBD exacerbations. One study reported that a cold spell was not significantly associated with the exacerbation of IBD [53], whereas another study reported a significant association between a heat wave and IBD exacerbation [54]. However, it is difficult to obtain conclusive results by generalizing seasonality and IBD exacerbation, as a quantitative analysis based on meta-analysis was unavailable.

The strength of this study is the length of the searched publication timeline (30 years) that was sufficient to consider the effect of the natural environment. The studies included in the meta-analysis had low overall heterogeneity and publication bias, and the reproducibility was high because we used the monthly data of the studies as the raw data. However, a limitation of our meta-analysis is that the results only presented the relevant intensity of significance but could not clarify which season was more relevant. In other words, there were only two studies that were presented as comparative statistics (odds ratio) between specific seasons [23, 47], so it was difficult to merge them with a meta-analysis. Another limitation of our study is that with regard to short-term temperature changes and air pollution other than seasonal variations, the number of studies reporting these characteristics was relatively small; therefore, a quantitative evidence synthesis could not be presented by meta-analysis. Cohort studies (three studies) were published only as conference abstracts, and a meta-analysis could not be performed owing to the lack of raw data for meta-analysis. Furthermore, only 6 out of 20 studies reported information on the duration of IBD morbidity, location of lesions, or medications administered [20–24, 50]. Moreover, 7 out of 20 studies did not report the number of patients who experienced IBD exacerbations [18, 20, 26, 27, 49, 51, 52], and 6 of the 11 studies reported different numbers of patients and cases of exacerbations [19, 21, 22, 25, 48, 50]. The abovementioned factors might have resulted in the underestimation or overestimation of the pooled estimate results of the meta-analysis. In addition, the method used for defining IBD exacerbation varied across studies; specifically, 7 out of 20 studies did not use a standard definition (i.e., cutoff for IBD activity measurements or inclusion criteria) (S4 Table). Among the included studies, there was one study in which the outpatient visit was defined as exacerbation [52]. There is a possibility that the outpatient visit may be different from the actual exacerbation time, so if other indicators such as disease activity are not considered together, the risk of misclassification may increase, and interpretation should be careful. This concern emerged from the lack of a clear-cut definition of IBD exacerbation, although attempts were made to reach a consensus on the exacerbation of UC [55], and may have caused potential bias in the individual studies. However, in view of the increasing importance of real-world evidence, this systematic review, which identifies the diversity of definitions of exacerbation in individual studies that were conducted in the clinical setting, is still meaningful.

We found that many studies included in this systematic review did not take into account that the seasonality of exacerbation could be affected by the seasonal habit or culture environment of each country. Only one study considered that exacerbation in summer was reduced since many holidays or vacations in the summer period as a country’s (Greece) characteristic, and the stress of IBD patients may be low [20]. According to the data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), among the countries included in this systematic review, European countries such as the UK, Spain, Italy, and Greece took paid leave of 20 days or more, but Canada, the United States, etc. North America and Asia, such as Japan and South Korea receive less than 20 days of paid leave [56]. As such, the habits, culture, and environment affected by the seasons, including the working environment, are different for each country, and this may affect the seasonal nature of exacerbation by acting differently as physical or psychiatric stress for IBD patients, and further research is needed. Another distinctive feature is that the countries and cities in all 20 published studies were located above the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere, especially at 30–50° latitude. This phenomenon of publications originating in the Northern Hemisphere could be considered a potential publication bias. According to the recent Global Burden of IBD study [57], given the increasing prevalence of IBD in all countries in the Southern Hemisphere, it will be necessary to encourage and include publications from countries in the Southern Hemisphere.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis showed a significant correlation between the exacerbation of IBD and seasonal variation. However, owing to the small number of included studies and the weak power of the pooled estimate value, the results should be cautiously interpreted. To support the preliminary findings of this research, high-quality, well-designed studies should be conducted.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Samsung Research Coaching Clinic (Samsung RCC) program, a non-financial in-hospital research promotion meeting program for residents and clinical fellows in Samsung Medical Center.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Chang JT. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2652–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2002697 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):720–7. Epub 20150901. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes EL, Kochar B, Long MD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Korzenik JR, et al. Modifiable Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission Among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Nationwide Database. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(6):875–81. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001121 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flicek CB, Sowa NA, Long MD, Herfarth HH, Dorn SD. Implementing Collaborative Care Management of Behavioral Health for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2022;7(2):97–103. Epub 20211202. doi: 10.1159/000521285 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Sloot KWJ, Amini M, Peters V, Dijkstra G, Alizadeh BZ. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Review of Known Environmental Protective and Risk Factors Involved. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(9):1499–509. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001217 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham DB, Xavier RJ. Pathway paradigms revealed from the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2020;578(7796):527–39. Epub 20200226. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2025-2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long GH, Tatro AR, Oh YS, Reddy SR, Ananthakrishnan AN. Analysis of Safety, Medical Resource Utilization, and Treatment Costs by Drug Class for Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the United States Based on Insurance Claims Data. Adv Ther. 2019;36(11):3079–95. Epub 20190927. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01095-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello SP, Soo W, Bryant RV, Jairath V, Hart AL, Andrews JM. Systematic review with meta-analysis: faecal microbiota transplantation for the induction of remission for active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(3):213–24. Epub 20170614. doi: 10.1111/apt.14173 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonovas S, Fiorino G, Allocca M, Lytras T, Nikolopoulos GK, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Biologic Therapies and Risk of Infection and Malignancy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(10):1385–97 e10. Epub 20160514. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.04.039 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cave DR, Freedman LS. Seasonal variations in the clinical of presentation of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Int J Epidemiol. 1975;4(4):317–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/4.4.317 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward M, Mitchell WD, Eastwood M. Complex nature of serum lysozyme activity: evidence of thermolability in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31(1):39–43. doi: 10.1136/jcp.31.1.39 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Hees PA, van Elteren PH, van Lier HJ, van Tongeren JH. An index of inflammatory activity in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1980;21(4):279–86. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.4.279 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myszor M, Calam J. Seasonality of ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1984;2(8401):522–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92600-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Don BA, Goldacre MJ. Absence of seasonality in emergency hospital admissions for inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1984;2(8412):1156–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91590-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a large, population-based study in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(2):350–8. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90202-v . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekbom A, Zack M, Adami HO, Helmick C. Is there clustering of inflammatory bowel disease at birth? Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(8):876–86. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Lucas S. Why do patients with ulcerative colitis relapse? Gut. 1990;31(2):179–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.179 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonnenberg A, Jacobsen SJ, Wasserman IH. Periodicity of hospital admissions for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(6):847–51. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson FH, Zeng L. Seasonal Pattern in the Relapses of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1995;9(2):113–7. doi: 10.1155/1995/462964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karamanolis DG, Delis KC, Papatheodoridis GV, Kalafatis E, Paspatis G, Xourgias VC. Seasonal variation in exacerbations of ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44(17):1334–8. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tezel A, Dagli U, Baysal C, Serin A, Over H, Ulker A, et al. The effect of seasonal variations on the onset and the relapse of ulcerative colitis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 1997;8(2):214–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vergara M, Fraga X, Casellas F, Bermejo B, Malagelada JR. Seasonal influence in exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1997;89(5):357–66. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis JD, Aberra FN, Lichtenstein GR, Bilker WB, Brensinger C, Strom BL. Seasonal variation in flares of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(3):665–73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soncini M, Triossi O, Leo P, Magni G, Giglio LA, Mosca PG, et al. Seasonal patterns of hospital treatment for inflammatory bowel disease in Italy. Digestion. 2006;73(1):1–8. Epub 20051201. doi: 10.1159/000090036 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai A, Guo Y, Shen Y, Xie Y, Zhu X, Lu N. Seasonality in flares and months of births of patients with ulcerative colitis in a Chinese population. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(5):1094–8. Epub 20081203. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0453-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaulieu DB, Ananthakrishnan AN, Zadvomova Y, Stein DJ, Mepani R, Antonik SJ, et al. Seasonal Variation in HRQOL and Disease Activity in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Tertiary Care Center Experience. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(5):A362. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(09)61661-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG, Saeian K. Ambient air pollution correlates with hospitalizations for inflammatory bowel disease: an ecologic analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(5):1138–45. Epub 20100830. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21455 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henderson P, Wilson DC. The Role of Seasonality in the Exacerbation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(5):S207. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. Epub 20210329. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dharmaraj R, Jaber A, Arora R, Hagglund K, Lyons H. Seasonal variations in onset and exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases in children. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8(1):696. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1702-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh AJ, Bryant RV, Travis SPL. Current best practice for disease activity assessment in IBD. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2016;13(10):567–79. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glossary of Meteorology Boston: American Meteorological Society; 2022 [Cited 2022 November 2]. http://glossary.ametsoc.org/wiki/.

- 33.Kelsen J, Baldassano RN. Inflammatory bowel disease: The difference between children and adults. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14(suppl_2):S9–S11. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Köppen W. The thermal zones of the Earth according to the duration of hot, moderate and cold periods and to the impact of heat on the organic world. Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 2011;20(3):351–60. doi: 10.1127/0941-2948/2011/105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5. Epub 20100722. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2127–33. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cramér H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rea LM, Parker RA. Designing and Conducting Survey Research: A Comprehensive Guide. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2014. 352 p. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winje E, Torgalsboen AK, Brunborg C, Lask B. Season of birth bias and anorexia nervosa: results from an international collaboration. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(4):340–5. Epub 20121016. doi: 10.1002/eat.22060 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549. Epub 20110210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. Chichester (UK). 2022. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-06.

- 43.Sedgwick P. Meta-analyses: heterogeneity and subgroup analysis. BMJ. 2013;346(jun24 2):f4040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yadav A, Unal M, Armstrong PR, Fauzi MN, Tony A, McGarry C, et al. Impact of patient age, gender and season of admission on length of stay in hospital for acute inflammatory bowel disease admissions. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:S525. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy222.930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yadav A, Kelly E, Armstrong PR, Fauzi MN, McGarry C, Shaw C, et al. Seasonal variations in acute hospital admissions with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:S505–S6. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy222.893 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stein AC, Gaetano JN, Jacobs J, Kunnavakkam R, Bissonnette M, Pekow J. Northern Latitude but Not Season Is Associated with Increased Rates of Hospitalizations Related to Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results of a Multi-Year Analysis of a National Cohort. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161523. Epub 20160831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161523 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peng JC, Ran ZH, Shen J. Seasonal variation in onset and relapse of IBD and a model to predict the frequency of onset, relapse, and severity of IBD based on artificial neural network. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(9):1267–73. Epub 20150515. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2250-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tinsley A, Wang L, Williams E, Ullman TA, Sands BE. Early Hospital Readmissions Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):S646. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung YS, Song CS, Kim ER, Park DI, Kim YH, Cha JM, et al. Seasonal variation in months of birth and symptom flares in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver. 2013;7(6):661–7. Epub 20130814. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.6.661 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duan R, Wu Y, Wang M, Wu J, Wang X, Wang Z, et al. Association between short-term exposure to fine particulate pollution and outpatient visits for ulcerative colitis in Beijing, China: A time-series study. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;214:112116. Epub 20210308. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112116 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding S, Sun S, Ding R, Song S, Cao Y, Zhang L. Association between exposure to air pollutants and the risk of inflammatory bowel diseases visits. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(12):17645–54. Epub 20211020. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17009-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manser CN, Kraus A, Frei T, Rogler G, Held L. The Impact of Cold Spells on the Incidence of Infectious Gastroenteritis and Relapse Rates of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Retrospective Controlled Observational Study. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2017;2(2):124–30. Epub 20170715. doi: 10.1159/000477807 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manser CN, Paul M, Rogler G, Held L, Frei T. Heat waves, incidence of infectious gastroenteritis, and relapse rates of inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective controlled observational study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1480–5. Epub 20130813. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.186 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, Maaser C, Chowers Y, Geboes K, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(10):965–90. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.OECD Social Policy Division DoE, Labour and Social Affairs. PF2.3: Additional leave entitlements for working parents Paris: OECD 2020 January [Cited 2022 November 2]. 2–3. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm.

- 57.Alatab S, Sepanlou SG, Ikuta K, Vahedi H, Bisignano C, Safiri S, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. 2020;5(1):17–30. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30333-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.