Abstract

The PhoP-PhoQ two-component system is necessary for the virulence of Salmonella spp. and is responsible for regulating several modifications of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Mutagenesis of the transcriptional regulator phoP resulted in the identification of a mutant able to activate transcription of regulated genes ∼100-fold in the absence of PhoQ. Sequence analysis showed two single-base alterations resulting in amino acid changes at positions 93 (S93N) and 203 (Q203R). These mutations were individually created, and although each resulted in a constitutive phenotype, the double mutant displayed a synergistic effect both in the induction of PhoP-activated gene expression and in resistance to antimicrobial peptides. The constitutive phoP gene was placed under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter to examine the kinetics of PhoP-activated gene induction and the resultant modifications of LPS. Gene induction and 2-hydroxymyristate modification of the lipid A were shown to occur within minutes of the addition of arabinose and to peak at 4 h. As the first constitutive mutant of phoP identified, this allele will be invaluable to future genetic and biochemical studies of this and likely other regulatory systems.

The PhoP-PhoQ two-component regulatory system controls the expression of genes necessary for virulence and survival of salmonellae within host macrophages (7, 18, 23). Within the macrophage phagosome, PhoP-PhoQ is activated to induce gene transcription (1). The regulated genes include those necessary for modification of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and resistance to the action of antimicrobial peptides, which likely increase bacterial survival within macrophages (10, 13). Additionally, PhoP-PhoQ is involved in the regulation of magnesium transport (9), resistance to the action of bile (32), and secretion of proteins by a type III mechanism (27).

PhoQ is a predicted transmembrane protein with a single periplasmic domain encompassing amino acids 44 to 191 (11). Evidence suggests that this periplasmic domain binds environmental factors such as Mg2+ (33, 34). PhoQ is a kinase that, upon sensing environmental signals, activates the DNA binding function of PhoP through a phosphorylation event (11) leading to PhoP-regulated gene activation.

Constitutive activation of two-component regulators has been reported for several systems in a variety of bacterial species (16, 17, 19, 28). Previously, a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium phoP locus mutant (pho24) was isolated that constitutively expressed PhoP-activated genes (pag) and repressed PhoP-repressed genes (prg) (21, 24). This mutation mapped to the gene encoding the membrane-bound kinase PhoQ (change from Thr to Ile at position 48), and not that encoding the DNA binding protein PhoP (11). The pho24 allele has a pleiotropic affect on S. enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence, including the attenuation of mouse virulence and survival within cultured macrophages, which suggested a temporal importance in the shift to PhoP-PhoQ activation during infection. This study describes the identification and characterization of a constitutive mutant of this regulatory system located in PhoP. The identification of this mutant will aid current and future studies of the signal transduction process and the interaction of PhoP with regulated gene promoters.

Identification and characterization of constitutive phoP mutants.

To generate mutations in the phoP gene, the following protocol was used. PCR primers were designed to bind to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the phoP gene, such that the 3′ primer contained a PstI site at its terminus and the 5′ primer contained a BamHI site at its terminus (JG31 and JG39, respectively). The 5′ primer contained the native ATG start codon with the BamHI site directly upstream of this translational start site. Upon amplification by PCR, the phoP gene was cloned into M13mp18 via the BamHI and PstI sites. Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) was purified from M13 phage. Approximately 10 μg of ssDNA was incubated in a 25-μl final volume with hydrazine (2 and 3.36 M final concentrations) or formic acid (3.7 and 6 M final concentrations) for 10 min at room temperature or sodium nitrite (1.2 M final concentration) for 60 min at room temperature. After chemical treatment, DNAs were diluted to 200 μl, precipitated, and resuspended in 20 μl of water. A 4-μl aliquot of each mutagenized DNA was then PCR amplified with primers at the 3′ end (JG31) and 5′ end (JG45) of the DNA. JG45 is similar to JG39, except it contains an XbaI site and the native ribosome binding site at its 5′ terminus in place of the BamHI site. The PCR products were digested with XbaI and PstI and cloned into the low-copy vector pWSK29 (8), in which the phoP gene is transcribed from the lac promoter of the vector. A portion of each ligation was electroporated into Escherichia coli DH5α. Following growth of cells in the entire ligation mix overnight in the presence of ampicillin, plasmid DNA was isolated. As a first screen, strain SIM547, which is a derivative of LB5010 (R-M+ galE recA phoP::Tn10d), was transformed with the isolated DNA. The S. enterica serovar Typhimurium phoN gene encodes a nonspecific acid phosphatase and controls the blue color phenotype of cells on agar plates containing the chromogenic substrate XP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) (21). phoN is transcriptionally activated by PhoP-PhoQ, and because SIM547 is PhoP-PhoQ null, this strain is white on plates containing XP. Upon transformation of SIM547 with each of the mutagenized pools, several blue colonies (n = 35) were observed (2 M hydrazine, 11.5% blue; 3.36 M hydrazine, 33% blue; 3.7 M formic acid, 2.8% blue; 6 M formic acid, 11% blue; and 1.2 M sodium nitrite, 9.3% blue). The plasmid DNA of all 35 blue colonies identified was isolated and transformed into two strains: JSG465, which is PhoP-PhoQ null and carries a transposon-generated fusion to a gene whose transcription is increased when PhoP-PhoQ is activated (pagB::MudJ); and JSG225, which contains a TnphoA insertion in pagD and is phenotypically PhoP-PhoQ null (PhoP−) and PhoN− (phoN2 zxx::6251dTn10-CAM [85% linked to phoN]). Of the 35 plasmids, only one (plasmid pPC3-2 from the 2 M hydrazine pool) resulted in considerable activation of the fusion protein in both JSG465 and JSG225. Several possibilities exist for the lack of activation of the other plasmids identified in the first screen. For example, phoN may require smaller amounts of active PhoP than pagB or pagD for activation, or, alternatively, the pool of SIM547 cells used for the transformation may have contained those with a phoN mutation, allowing expression in the absence of PhoP. The latter is less likely because the percentage of blue isolates increased with increasing concentrations of hydrazine or formic acid used with the DNA. Table 1 shows the β-galactosidase or alkaline phosphatase activities of the pho24 strain with each of the reporter fusions examined, as well as those of various strains containing either pPC3-2 or a wild-type (control) phoP plasmid (pWSK200). These data show that pPC3-2 results in 94- and 63-fold activations of pagD and pagB, respectively. In addition, slightly higher levels of PhoP-activated gene transcription were observed with pPC3-2 than with the pho24 (PhoQ constitutive) mutation. Therefore, this represents the first mutant of the virulence regulatory protein PhoP that is able to activate genes of the PhoP regulon in the absence of PhoQ signaling.

TABLE 1.

Effect of phoP-constitutive alleles on pag transcriptional activity

| Background strain | Relevant genotype | Relevant phenotype | Plasmid | Reporter activity (U)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSG208 | pho24 pagB::MudJ | PhoPQ constitutive, pagB-lacZ | NAb | 321 ± 16 (β) |

| JSG465 | pagB::MudJ phoP::Tn10d-Tet | PhoP−, pagB-lacZ | pWSK200c | 6.2 ± 2 (β) |

| JSG465 | pagB::MudJ phoP::Tn10d-Tet | PhoP−, pagB-lacZ | pPC3-2d | 390 ± 14 (β) |

| JSG225 | pagD::TnphoA phoP::Tn10d-Tet phoN2 zxx::6251Tn10d-Cam | PhoP−, pagD-phoA | pWSK200 | 8.3 ± 2 (A) |

| JSG225 | pagD::TnphoA phoP::Tn10d-Tet phoN2 zxx::6251Tn10d-Cam | PhoP−, pagD-phoA | pPC3-2 | 784 ± 22 (A) |

| JSG225 | pagD::TnphoA phoP::Tn10d-Tet phoN2 zxx::6251Tn10d-Cam | PhoP−, pagD-phoA | pPSK200-691e | 124 ± 8 (A) |

| JSG225 | pagD::TnphoA phoP::Tn10d-Tet phoN2 zxx::6251Tn10d-Cam | PhoP−, pagD-phoA | pPSK200-7974f | 540 ± 10 (A) |

| JSG208 | pho24 pagD::TnphoA phoN2 zxx::6251Tn10d-Cam | PhoPQ constitutive, pagD-phoA | NA | 674 ± 19 (A) |

Units reported as described by Miller (22) for β-galactosidase (β) or alkaline phosphatase (A).

NA, not applicable.

pWSK29 with the wild-type phoP gene.

pWSK29 with the double-mutant, constitutive phoP gene.

pWSK29 with the single-mutant (784 A→G; Q203R), constitutive phoP gene.

pWSK29 with the single-mutant (418 G→A; S93N), constitutive phoP gene.

Analysis of the pPC3-2-mediated PhoP-constitutive phenotype.

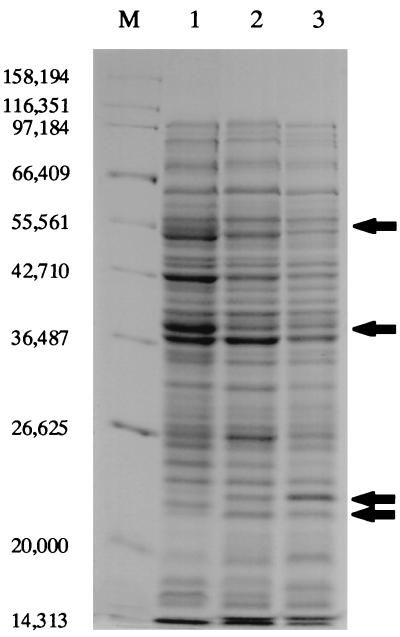

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains containing the pho24 allele activate and repress the production of a number of proteins (Pag and Prg) that are obvious by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis. In addition, activation of the regulon results in a variety of distinguishing phenotypes, including increased resistance to certain antimicrobial peptides (10, 12, 25), which are potent antibacterial factors that are ubiquitous in the animal and plant kingdoms (2, 36). Therefore, strains carrying the pPC3-2 plasmid were examined by SDS-PAGE for alteration of protein expression and for altered resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Whole-cell lysates of the PhoP− and PhoPc (pho24) strains and of PhoP− strain with pPC3-2 were prepared from overnight cultures as previously described (11) and electrophoresed on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. As seen in Fig. 1, PhoPc (pho24) and PhoP− with pPC3-2 lysates look similar, and both are different from PhoP− lysate at several locations (the most obvious of which are marked by an arrow). Therefore, the protein pattern imparted by the pPC3-2 plasmid appears to be the “constitutive pattern” and is accomplished in the absence of PhoQ. In addition to the similarities in protein profiles of the pPC3-2-containing strain and the PhoQ-Ile48 mutant strain, there exist some protein differences between these strains, including differences in intensity between some common activated species. This may be due to slight differences in promoter affinity between the mutant and the wild-type phoP alleles.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of protein expression patterns by SDS-PAGE. Whole-cell proteins of the PhoP− (lane 1) strain, the PhoP− strain with plasmid pPC3-2 (lane 2), and the PhoQ-constitutive (pho24) (lane 3) strain were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. The expression pattern of lane 2 containing proteins of the PhoP− strain with plasmid pPC3-2 is similar to that of lane 3 containing proteins of the PhoQ-constitutive (pho24) strain and dissimilar from that of lane 1, further demonstrating the constitutive phenotype imparted by the pPC3-2 constitutive phoP allele. Arrows point to the most obvious protein differences between those with the PhoP-constitutive pattern (lanes 2 and 3) and the PhoP− pattern (lane 1). Lane M contains the molecular mass standards, the sizes of which are given to the left in daltons.

To examine the antimicrobial peptide resistance phenotype, MIC assays were conducted with the PhoP− strain carrying pPC3-2 or the control plasmid pWSK200. The results showed that the PhoP− strain with pPC3-2 had an eightfold increase in resistance to PG-1, an 18-amino-acid peptide with a β-sheet structure isolated from porcine neutrophils (data not shown). Therefore, the presence of the pPC3-2 plasmid resulted in increased resistance to antimicrobial peptides, which was previously known to depend upon the level of activated PhoP in the cell.

DNA sequencing and site-directed mutagenesis determine the genetic basis of the pPC3-2-mediated PhoP-constitutive phenotype.

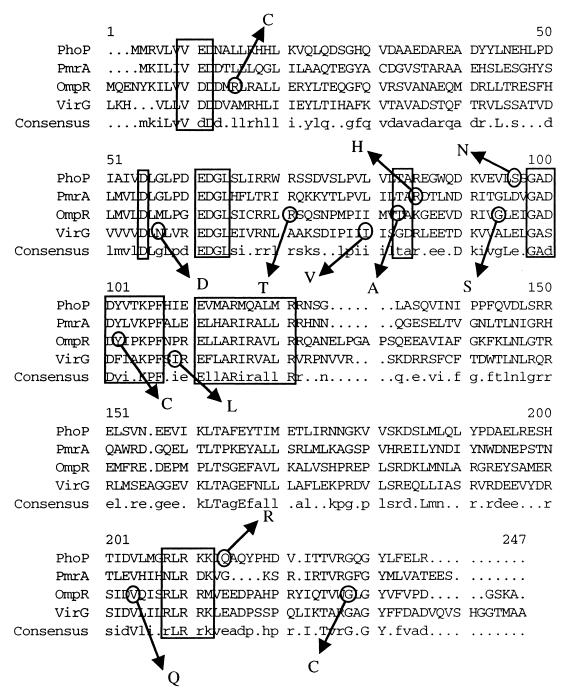

To determine the genetic basis of the constitutive phenotype associated with plasmid pPC3-2, the phoP gene was sequenced. Sequence analysis showed two mutations: a G→A at base position 418, resulting in an S→N alteration at amino acid 93; and an A→G at base position 748, resulting in a Q→R alteration at amino acid 203 (base positions correspond to those defined by Miller et al. [23]; GenBank accession no. M24424). These residues flank consensus regions near the amino and carboxy termini and are novel among OmpR family regulatory protein constitutive mutations that have been identified (Fig. 2). Interestingly, OmpR, PmrA, and VirG constitutive mutations that have been identified also frequently flank or are located within consensus regions (3, 16, 17, 19, 20, 26, 28, 29, 31). To determine if one or both of these mutations was sufficient for the observed constitutive phenotype, each mutation was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. Primers JG68 and JG69 were made to contain the mutations at bases 418 and 748, respectively. Mutagenesis was accomplished with the Muta-Gene phagemid kit (Bio-Rad) and confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. The resulting plasmids, pPSK200-691 (containing the 784 A→G mutation) and pPSK200-7974 (containing the 418 G→A mutation), were transformed into strain JSG225. Upon analysis of alkaline phosphatase activity, it was shown that both mutations resulted in activation of the pagD::TnphoA fusion, with PhoP S93N resulting in 65-fold activation and PhoP Q203R resulting in 15-fold activation. These activities, though, were less than that of both mutations together (94-fold activation). As further verification of the constitutive phenotype imparted by the PhoP S93N and PhoP Q203R single mutations, strains carrying the mutant plasmids were examined in the peptide resistance assay. Both single mutations resulted in a MIC requirement that was intermediate between that of the negative control and that of the strain carrying both mutations together (data not shown). This further suggests that these mutations act synergistically to result in the observed high-level PhoP activation.

FIG. 2.

Protein alignment of OmpR-type regulators with known constitutive mutations. The protein sequences aligned include those of PhoP (GenBank accession no. M24424), PmrA (accession no. L13395), OmpR (accession no. J01656), and VirG (29). Circled residues with arrows denote those changes that have been shown to result in a constitutive phenotype. Highly conserved consensus regions located near these sites, including the aspartic acid residue (D) predicted to be a site of phosphorylation, are boxed.

Use of the constitutive phoP gene to determine the kinetics of pag activation and LPS modification.

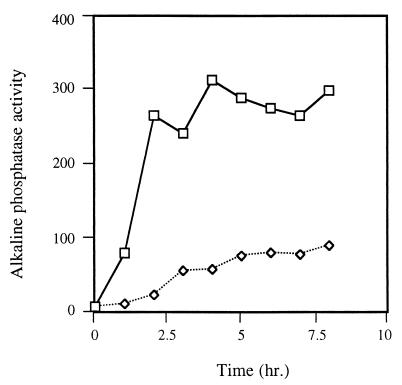

It has been shown by Garcia-Vescovi et al. (9) that upon chelation of Mg2+ in the media, activation of a PhoP-regulated locus, psiD, occurs rapidly and peaks by 5 h. We placed the constitutive phoP gene under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter and used this to determine the kinetics of activation of several pag genes as well as the modification of lipid A with 2-hydroxymyristate, which can be added as a result of activation of an unknown PhoP-activated gene(s). To construct an arabinose-inducible phoP-constitutive gene, the phoP gene was PCR amplified from pPC3-2 with primers JG225 and JG45, digested with enzymes HindIII and XbaI (whose sites were incorporated into the 5′ end of primers JG225 and JG45, respectively), and ligated into vector pBAD18 (15). Following transformation of E. coli DH5α, the correct plasmid was identified (pPCBAD3-2). Upon transformation of the clone into various S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains, cells were grown to mid-log phase, and arabinose was added to a concentration of 0.05 or 0.2% (both concentrations have been shown to maximally induce the pBAD promoter). Cells were harvested at time points before and after arabinose addition and examined for pag gene activation by β-galactosidase or alkaline phosphatase assays or for LPS modifications as described below. Upon induction of the mutant phoP with arabinose in a PhoP− background, activation of pagD was observed within minutes and peaked at 4 h (Fig. 3). Nearly identical kinetics were observed with other PhoP-activated genes tested (data not shown). Because these kinetics are similar to those reported by Garcia-Vescovi et al. (9), this finding suggests that Mg2+ signaling, which is sensed by PhoQ and communicated to PhoP via a phosphotransfer event, is as efficient as altering the presence or absence of an “activated” PhoP protein.

FIG. 3.

Activation of pagD transcription by arabinose-inducible PhoP production. PhoP− strains carrying a pagD::TnphoA reporter and the pPCBAD3-2 plasmid were grown to log phase and then not supplemented or supplemented with arabinose. Alkaline phosphatase activity was monitored over time. Lines with squares are results from cultures with arabinose added at time zero, and those with diamonds are results from cultures without arabinose added.

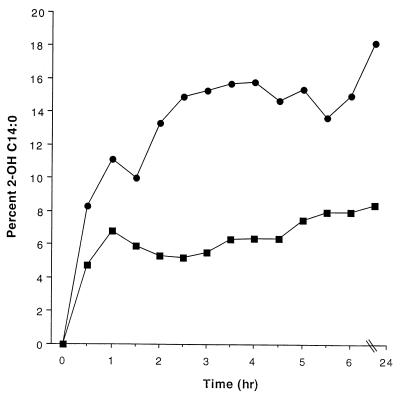

Numerous modifications of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LPS are controlled by PhoP (12–14), including modification of the lipid A with 2-hydroxymyristate. PhoP-mediated modification of LPS within macrophage phagosomes is thought both to aid in resistance of the bacterium to resident antimicrobial peptides and to alter immune recognition and cytokine response (13, 35). For modification of LPS to be effective, it must occur rapidly upon PhoP activation. To examine the kinetics of LPS modification, lipid A was isolated at various time points after activation of the mutant phoP allele with arabinose. LPS was isolated by the Mg2+-ethanol precipitation procedure as described by Darveau and Hancock (6). Lipid A was isolated from LPS by hydrolysis in 1% SDS at pH 4.5 (4), and the fatty acids were analyzed as methyl esters by capillary gas chromotography GC with flame ionization detection as described previously (5, 30). The identities of the individual fatty acid chains were confirmed by capillary GC with electron impact mass spectrometry. These experiments showed that, upon activation of phoP, the amount of 2-hydroxymyristate present in lipid A isolated from induced phoP mutant bacteria was two- to threefold higher than the amount present in lipid A isolated from noninduced phoP mutant bacteria. Upon induction, the amount of 2-hydroxymyristate increased rapidly, with greater than 15% of the lipid A containing this modification within 4 h, and was maintained throughout the course of the assay (Fig. 4). Similar to the induced phoP mutant strain, the phoQ-constitutive strain (pho24) demonstrated an increase in the amount of 2-hydroxymyristate with more than 25% of the lipid A containing this modification within 4 h (data not shown). Finally, a phoP-null strain gave amounts of 2-hydroxymyristate similar to those of the noninduced phoP mutant (data not shown). These results demonstrate that pag activation and modification of lipid A with 2-hydroxymyristate occur with similar kinetics, confirming the assumption that, upon PhoP-activation, pag gene transcription, Pag enzymatic activity, and LPS modification and turnover all occur fairly rapidly. Rapid modification of the LPS is likely necessary for Salmonella's intracellular survival by providing resistance to the host's innate immune system and by altering immune system recognition of this pathogen.

FIG. 4.

Activation of 2-hydroxymyristate lipid A (2-OH C14:0) modification by arabinose-inducible PhoP production. A PhoP− strain carrying the pPCBAD1 plasmid was grown to log phase and then not supplemented or supplemented with arabinose (0.2%). The percentage of 2-hydroxymyristate lipid A modification was monitored over time by GC analysis. Solid circles represent a culture with arabinose added at time zero, and solid squares represent a culture without arabinose added. The experiment presented was representative of three separate experiments.

The identified constitutive phoP allele will be invaluable in future work defining the PhoP-PhoQ regulon. This phoP mutant will aid in the definition of the unknown molecular events of PhoP interaction with both activated and repressed gene promoters. Furthermore, this mutant will be used to test the induction kinetics of other PhoP-PhoQ-mediated phenotypes, such as antimicrobial peptide and bile resistance, and type III-mediated secretion of proteins involved in eukaryotic cell invasion.

Acknowledgments

We thank IntraBiotics Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for providing protegrin (PG-1) and Jennifer Van Velkinburgh for her technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants AI30479 (S.I.M.) and AI43521 (J.S.G.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alpuche-Aranda C M, Swanson J A, Loomis W P, Miller S I. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bevins C L. Antimicrobial peptides as agents of mucosal immunity. Ciba Found Symp. 1994;186:250–260. doi: 10.1002/9780470514658.ch15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brissette R E, Tsung K, Inouye M. Intramolecular second-site revertants to the phosphorylation site mutation in OmpR, a kinase-dependent transcriptional activator in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3749–3755. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3749-3755.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caroff M, Tacken A, Szabo L. Detergent-accelerated hydrolysis of bacterial endotoxins and determination of the anomeric configuration of the glycosyl phosphate present in the “isolated lipid A” fragment of the Bordetella pertussis endotoxin. Carbohydr Res. 1988;175:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(88)84149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darveau R P, Cunningham M D, Bailey T, Seachord C, Ratcliffe K, Bainbridge B, Dietsch M, Page R C, Aruffo A. Ability of bacteria associated with chronic inflammatory disease to stimulate E-selectin expression and promote neutrophil adhesion. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1311–1317. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1311-1317.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darveau R P, Hancock R E W. Procedure for isolation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides from both smooth and rough Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium strains. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:831–838. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.831-838.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fields P I, Swanson R V, Haidaris C G, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu R, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Vescovi E, Soncini F C, Groisman E A. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groisman E A, Parra-Lopez C, Salcedo M, Lipps C J, Heffron F. Resistance to host antimicrobial peptides is necessary for Salmonella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11939–11943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunn J S, Hohmann E L, Miller S I. Transcriptional regulation of Salmonella virulence: a PhoQ periplasmic domain mutation results in increased net phosphotransfer to PhoP. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6369–6373. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6369-6373.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunn J S, Miller S I. PhoP-PhoQ activates transcription of pmrAB, encoding a two-component regulatory system involved in Salmonella typhimurium antimicrobial peptide resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6857–6864. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6857-6864.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo L, Lim K, Gunn J S, Bainbridge B, Darveau R, Hackett M, Miller S I. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science. 1997;276:250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo L, Lim K B, Poduje C M, Daniel M, Gunn J S, Hackett M, Miller S I. Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell. 1998;95:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guzman L-M, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han D C, Winans S C. A mutation in the receiver domain of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens transcriptional regulator VirG increases its affinity for operator DNA. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlocker S L, Rampersaud A, Yang W-P, Inouye M. Phenotypic revertant mutations of a new OmpR2 mutant (V203Q) of Escherichia coli lie in the envZ gene, which encodes the OmpR kinase. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1956–1960. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1956-1960.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohmann E L, Oletta C A, Killeen K P, Miller S I. phoP/phoQ-deleted Salmonella typhi (TY800) is a safe and immunogenic single dose typhoid fever vaccine in volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1408–1414. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin S, Song Y, Pan S Q, Nester E W. Characterization of a virG mutation that confers constitutive virulence gene expression in Agrobacterium. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanamaru K, Mizuno T. Signal transduction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli: a novel mutant of the positive regulator, OmpR, that functions in a phosphorylation-independent manner. J Biochem. 1992;111:425–430. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kier L D, Weppelman R, Ames B N. Regulation of two phosphatases and a cyclic phosphodiesterase of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:420–428. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.420-428.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller S I, Kukral A M, Mekalanos J J. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5054–5058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller S I, Mekalanos J J. Constitutive expression of the PhoP regulon attenuates Salmonella virulence and survival within macrophages. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2485–2490. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2485-2490.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller S I, Pulkkinen W S, Selsted M E, Mekalanos J J. Characterization of defensin resistance phenotypes associated with mutations in the phoP virulence regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3706–3710. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3706-3710.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nara F, Matsuyama S, Mizuno T, Mizushima S. Molecular analysis of mutant ompR genes exhibiting different phenotypes as to osmoregulation of the ompF and ompC genes of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;202:194–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00331636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pegues D A, Hantman M J, Behlau I, Miller S I. PhoP/PhoQ transcriptional repression of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes: evidence for a role in protein secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:169–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roland K L, Martin L E, Esther C R, Spitznagel J K. Spontaneous pmrA mutants of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 define a new two-component regulatory system with a possible role in virulence. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4154–4164. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4154-4164.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheeren-Groot E P, Rodenburg K W, den Dulk-Ras A, Turk S C H J, Hooykaas P J. Mutational analysis of the transcriptional activator VirG of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6418–6426. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6418-6426.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Somerville J E J, Cassiano L, Bainbridge B, Cunningham M D, Darveau R P. A novel Escherichia coli lipid A mutant that produces an antiinflammatory lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Investig. 1996;97:359–365. doi: 10.1172/JCI118423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuzuki M, Aiba H, Mizuno T. Gene activation by the Escherichia coli positive regulator, OmpR. Phosphorylation-independent mechanism of activation by an OmpR mutant. J Mol Biol. 1994;242:607–613. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Velkinburgh J C, Gunn J S. PhoP-PhoQ-regulated loci are required for enhanced bile resistance in Salmonella spp. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1614–1622. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1614-1622.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vescovi E G, Ayala Y M, Di Cera E, Groisman E A. Characterization of the bacterial sensor protein PhoQ. Evidence for distinct binding sites for Mg2+ and Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1440–1443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waldburger C D, Sauer R T. Signal detection by the PhoQ sensor-transmitter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26630–26636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wick M J, Harding C V, Twesten N J, Normark S J, Pfeifer J D. The phoP locus influences processing and presentation of S. typhimurium antigens by activated macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zasloff M. Antibiotic peptides as mediators of innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:3–7. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90115-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]