Abstract

BACKGROUND

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic necessitated an abrupt transition to exclusive virtual interviewing for maternal-fetal medicine fellowship programs.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to assess the maternal-fetal medicine fellowship program directors’ approaches to exclusive virtual interviews and to obtain program director feedback on the virtual interview experience to guide future interview cycles.

STUDY DESIGN

A novel cross-sectional online survey was distributed through the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine to program directors after the completion of the interview season, but before the results of the National Resident Matching Program on October 14, 2020. Survey data were collected anonymously and managed using secure Research Electronic Data Capture electronic data capture tools.

RESULTS

Overall 71 of 89 program directors (80%) responded. All respondents completed their 2020 interviews 100% virtually. Nearly half of program directors (33 of 68, 49%) interviewed more candidates in 2020 than in 2019. Of those who interviewed more candidates in 2020, the mean number of additional candidates per fellowship position was 5.8 (standard deviation, ±3.8). Almost all program directors reported no (35 of 71, 49%) or minimal (34 of 71, 48%) negative impact of technical difficulties on their virtual interview processes. Most programs structured their interview to a half day (4 hours) or less for the candidates. Many programs were able to adapt their supplemental interview materials and events for the candidates into a virtual format, including a virtual social event hosted by 31 of 71 programs (44%). The virtual social event was most commonly casual and led by current fellows. Ultimately, all program directors reported that the virtual interview experience was as expected or better than expected. However, most program directors felt less able to provide candidates with a comprehensive and accurate representation of their program on a virtual platform compared with their previous in-person experiences (46 of 71 [65%] reported minimally, moderately, or significantly less than in-person). In addition, most program directors felt their ability to get to know candidates and assess their “fit” with the program was less than previous in-person years (44 of 71 [62%] reported minimally, moderately, or significantly less than in-person). In a hypothetical future year without any public health concerns, there were 23 of 71 respondents (32%) who prefer exclusive in-person interviews, 24 of 71 (34%) who prefer exclusive virtual interviews, and 24 of 71 (34%) who prefer a hybrid of virtual and in-person interviews.

CONCLUSION

The virtual interview experience was better than expected for most program directors. However, most program directors felt less able to present their programs and assess the candidates on a virtual platform compared with previous in-person experiences. Despite this, most program directors are interested in at least a component of virtual interviewing in future years. Future efforts are needed to refine the virtual interview process to optimize the experience for program directors and candidates.

Key words: COVID, COVID-19, fellowship, fellowship interviews, graduate medical education, maternal-fetal medicine, program directors, SARS-CoV-2, virtual interviews

AJOG MFM at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

This study aimed to assess maternal-fetal medicine program directors’ (PDs) approaches to virtual interviews and to obtain PD feedback on the virtual interview experience to guide future interview cycles.

Key findings

All PDs reported that the virtual interview process went as expected or better than expected. Most PDs felt less able to display their programs and evaluate candidates virtually compared with in-person. Two-thirds of PDs are interested in some component of virtual interviewing in future years.

What does this add to what is known?

PDs are interested in a component of virtual interviewing in future years. Future efforts should aim to refine the virtual interview process to optimize the experience for programs and candidates.

Introduction

The onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in March 2020 necessitated an abrupt change to the planned 2020 interview process for maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) fellowship training programs. Although community prevalence varied across the country, immediate efforts were made to slow the spread of disease nationally. Many local health departments quickly implemented restrictions on in-person gatherings and most academic institutions initiated a travel ban for faculty and trainees. These restrictions prohibited many programs from hosting usual in-person fellowship interview events and prohibited many candidates from traveling freely to interview at programs across the country. In accordance with public health recommendations, to protect the safety of candidates and programs and ensure a fair process across programs, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) made a recommendation for exclusive virtual interviews for the 2020 application season in April 2020.

The concept of incorporating some aspect of virtual interviewing for graduate medical education training programs has been long discussed.1, 2, 3 The financial cost and the time spent away from clinical training make the process burdensome for candidates.4, 5, 6, 7 There are also substantial recruitment costs for programs.8 However, this transition had not been made because, outside of a pandemic, it was difficult to get consensus among programs to proceed with a virtual format. In-person interviews have the benefit of additional time and face-to-face interactions with candidates and program faculty and trainees. These interactions weigh heavily in determining selection of candidates. In the 2018 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) program director (PD) survey, the most important factors in ranking applicants were candidate's interpersonal skills, interactions with faculty during interview and visit, and interactions with house staff during interview and visit.9 A primary concern with virtual interviews has been if these factors can be reliably assessed on a virtual platform.

Given the unique situation of a public health crisis forcing an unexpected transition to virtual interviews in 2020, we aimed to evaluate the virtual interview experience in comparison with previous in-person interview cycles. The objective of this study was to assess MFM fellowship PDs’ approaches to virtual interviews in the 2020 season and to obtain PD feedback on the virtual interview experience. These data can be used to guide discussion in determining the optimal approach to fellowship interviews in future years outside of a pandemic.

Materials and Methods

A novel cross-sectional online survey was developed by the SMFM Fellowship Affairs Committee. This is a committee of the SMFM whose aim is to support, expand, and foster education, administrative, and research issues relating to fellows in MFM. It consists of 20 members who each complete a 3-year term. The survey consisted of 20 multiple choice questions with built-in branching logic and options for free text explanations for certain responses. The survey was reviewed for clarity and the survey instrument was tested by 4 members of the committee. The survey gathered data on how each PD structured their virtual interview processes in 2020 and their perception of virtual interviews in comparison with past in-person interviews using a Likert scale (complete survey available as Appendix A).

The survey was electronically distributed by SMFM to the PD list serve on September 22, 2020. Notably, 2 reminder emails were sent 10 days before and 1 day before the close of the survey on October 13, 2020. The emails containing the survey link stated that the survey is optional, that completion of the survey is considered consent to participate in this study, and that the responses would be coded anonymously. The time window to complete the survey was intentionally set for after the completion of the interview season, but before the release of the results of the NRMP MFM match on October 14, 2020, to avoid bias based on perceived success of the match.

Survey data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Nashville, TN) electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.10 , 11 REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies. Descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses were performed using STATA 12.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). This study was determined to be exempt from institutional review board review by the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Results

There are 97 MFM programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). There are 8 programs that have not listed their information with SMFM. Thus, the survey was distributed by SMFM to 89 PDs. There were 71 responses (80%) from those who received the survey. This represents input from 73% of all ACGME-accredited PDs. There were 3 respondents with new programs in 2020, and thus, they could not answer questions regarding previous interview years.

In 2020, 71 of 71 respondents (100%) reported they completed 100% of their interviews virtually in accordance with SMFM recommendations. In comparison, in 2019, 0 of 68 (0%) completed 100% of interviews virtually and only 2 of 68 (3%) reported 10% virtual interviews. The remaining 66 of 68 PDs (97%) had 0% virtual interviews in 2019.

Excluding the 3 new 2020 programs, the mean number of candidates interviewed per fellowship position increased significantly from 19.4 (standard deviation, ±6.5) in 2019 to 21.3 (standard deviation, ±7.8) in 2020 (P<.01). Overall, 33 of 68 PDs (49%) interviewed more candidates in 2020 than in 2019. Of those 33 PDs who interviewed more candidates in 2020, the mean number of additional candidates per fellowship position was 5.8 (standard deviation, ±3.8).

The most commonly cited reason for interviewing more candidates in 2020 was caused by concern that candidates accepted more interviews than past years resulting in an increased risk of not filling their fellowship positions (16 of 33, 49%). The next most commonly cited reason was concern that their programs would not be showcased well virtually and that they were at risk of not filling their fellowship positions (5 of 33, 15%). Other reasons were that the candidates were of better quality this year than previous years, the virtual interview process simply made it easier for programs and candidates to do more interviews, and programs offered the same number of interviews but had many fewer candidates decline or cancel their interviews. Only 5 of 33 PDs (15%) said they were already planning to interview more candidates in 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The most commonly used platform for virtual interviews was Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc, San Jose, CA), used by 65 of 71 programs (92%). There were 4 of 71 programs (6%) that used Cisco Webex (Cisco Systems, Milpitas, CA) and 1 each that used Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), Thalamus (Thalamus, Santa Clara, CA), and ePosterBoards (ePosterBoards, LLC, Charlestown, MA). Almost all PDs reported no (35 of 71, 49%) or minimal (34 of 71, 48%) negative impact of technical difficulties on their virtual interview process. Only 2 of 71 (3%) reported moderate negative impact of technical difficulties and none reported a significant negative impact.

Many programs (34 of 71, 48%) structured their interviews to a half day (4 hours) for the candidates. There were 16 of 71 programs (23%) that interviewed candidates for 3 hours, 13 of 71 (18%) for 5 hours, 6 of 71 (9%) for 6 hours or more, and 2 of 71 (3%) for 2 hours or less. Many programs adapted their supplemental interview materials and events for the candidates into a virtual format (Table ). There were 31 of 71 programs (44%) that hosted a virtual social event. Of those programs hosting a social event, 31 of 31 (100%) involved their fellows, 6 of 31 (19%) involved their MFM faculty, 2 of 31 (7%) involved their residents, and 1 of 31 (3%) involved faculty from other divisions or departments. Most programs (27 of 31, 87%) held their virtual social event the night before the interview day. Notably, 2 programs held their virtual social event on the interview day and 2 held it at other times. Most programs kept the virtual social event brief at 1 hour (13 of 31, 42%) or 30 to 59 minutes (7 of 31, 23%). There were 9 of 31 (29%) that were >1 hour but <2 hours and only 2 of 31 (7%) that were 2 hours or more. PDs were asked to summarize the format and focus of their event, and overwhelmingly, this was an unstructured, casual event that was most commonly led by current fellows. Most programs stated it was intended for casual conversation and question and answer sessions with the fellows. Many programs reported using breakout rooms with or without themes to allow for smaller groups for conversation.

Table.

Supplemental interview day materials or events in 2019 compared with 2020

| Interview event | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual social event | 1 (1.4) | 31 (43.7) |

| In-person social event | 41 (57.8) | 0 (0) |

| Mailed physical welcome package | 8 (11.3) | 26 (36.6) |

| Electronic materials or links about your institution or city | 31 (43.7) | 54 (76.1) |

| Prerecorded program overview presentation | 1 (1.4) | 13 (18.3) |

| Live program overview presentation | 58 (81.7) | 48 (67.6) |

| Prerecorded virtual tour | 2 (2.8) | 31 (48.7) |

| Live virtual tour | 0 (0) | 10 (14.1) |

| In-person tour | 60 (84.5) | 0 (0) |

| In-person room for casual conversation between candidates and current fellows or faculty | 58 (81.7) | 3 (4.2) |

| Virtual room for casual conversation between candidates only | 0 (0) | 9 (12.7) |

| Virtual room for casual conversation between candidates and current fellows or faculty | 2 (2.8) | 44 (62.0) |

Values are number (percentage) unless indicated otherwise.

Rhoades. Maternal-fetal medicine program director experience of virtual interviews. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

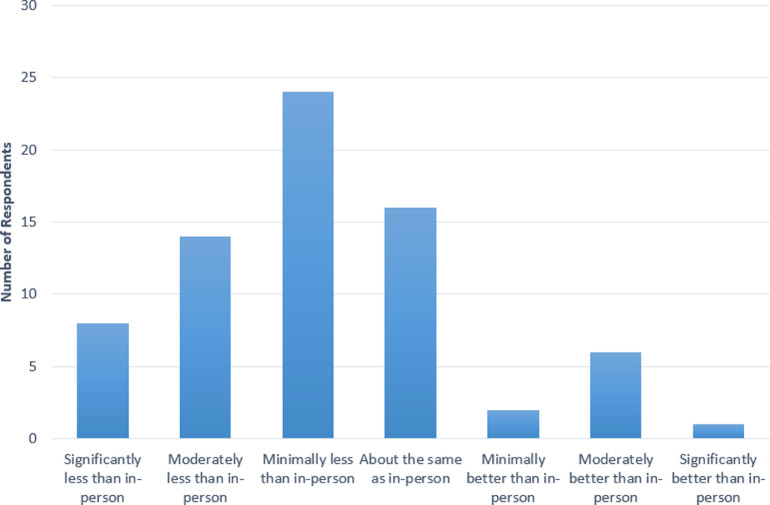

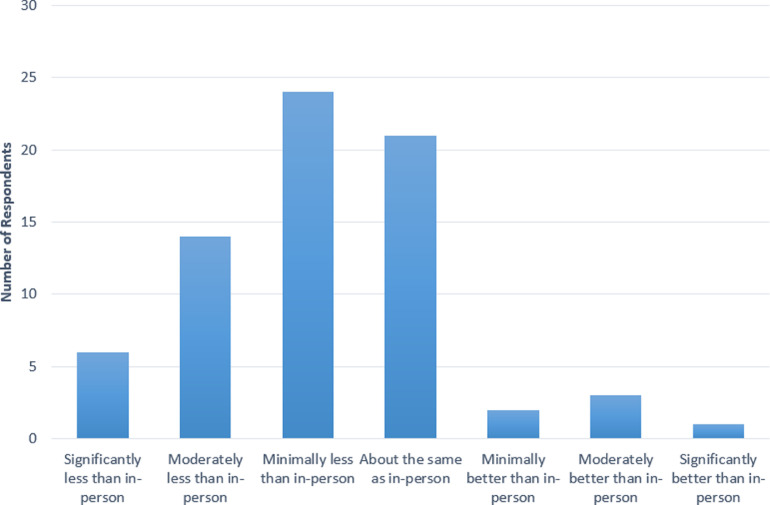

PDs’ overall experience with the virtual interview process was favorable. All PDs reported the experience was as expected (7 of 71, 10%), slightly better than expected (16 of 71, 23%), or better than expected (48 of 71, 68%). No PDs reported the experience was slightly worse than expected (0 of 71, 0%) or worse than expected (0 of 71, 0%). However, most PDs felt less able to provide candidates with a comprehensive and accurate representation of their programs on a virtual platform compared with their previous in-person experiences (46 of 71 [65%] reported minimally, moderately, or significantly less than in-person). In contrast, 9 of 71 (13%) felt they were minimally, moderately, or significantly better able to represent their programs on a virtual platform, and 16 of 71 (23%) felt it was the same as in-person (Figure 1 ). Similarly, most PDs felt their ability to get to know candidates and assess their “fit” with the program was less than previous in-person years (44 of 71 [62%] reported minimally, moderately, or significantly less than in-person). There were 21 of 71 PDs (30%) who felt their ability to assess the candidates was the same as in-person and only 6 of 71 (9%) who felt they were minimally, moderately, or significantly more able to assess the candidates on a virtual platform (Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Program director ability to provide a comprehensive and accurate representation of their program virtually

Rhoades. Maternal-fetal medicine program director experience of virtual interviews. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

Figure 2.

Program director ability to evaluate candidates and assess their "fit" with the program virtually

Rhoades. Maternal-fetal medicine program director experience of virtual interviews. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021.

In a hypothetical future year without any public health concerns, PDs have varied opinions on the extent to which they desire a virtual component to the fellowship interview process. There were 23 of 71 PDs (32%) who prefer exclusive in-person interviews, 24 of 71 (34%) who prefer exclusive virtual interviews, and 24 of 71 (34%) who prefer a hybrid of virtual and in-person interviews in the future. Of those PDs who selected a hybrid of virtual and in-person interviewing, 10 of 24 (42%) prefer to complete a first round of interviews virtually and invite select candidates for in-person interviews, 9 of 24 (38%) prefer to allow candidates to choose between virtual or in-person interviews and offer interview days of each modality, and 5 of 24 (21%) prefer to complete a first round of interviews virtually and allow candidates to choose if they desire an in-person visit.

Comment

Principal findings

We found that MFM fellowship PDs were able to quickly adapt their interview days to a virtual format and overall felt their experiences with the virtual interview process in 2020 were better than expected. However, most PDs felt they could not adequately portray their programs or get to know the candidates as well on a virtual platform compared with previous in-person experiences. Nonetheless, approximately two-thirds of PDs are interested in exclusive virtual interviews or a hybrid of virtual and in-person interviews in future years.

Results

Our results are consistent with our colleagues in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery (FPMRS) who conducted their virtual interview season a few months before our subspecialty. A survey of FPMRS PDs found that 88.9% felt virtual interviews were effective in evaluating candidates and 86.7% were satisfied with the virtual interview process. Despite this, only 31.1% indicated that they prefer virtual interviews to in-person interviews. Nonetheless, 60% of PDs felt they would be likely to use virtual interviews in the future.12 Likewise, other surgical specialty training programs have also found the virtual interview process effective and efficient, but not as satisfactory in the ability to get to know the candidates, faculty, and program.13, 14, 15, 16 These studies and ours indicate that across many specialties, programs recognize that virtual interviews are cost effective and efficient and it may be reasonable to not return to an entirely in-person interview experience in future years.

Clinical implications

The data from this survey provide important feedback from the PD perspective on the new experience of exclusive virtual interviewing. These data can inform individual MFM programs and the SMFM regarding the optimal approach to fellowship interviews in future interview cycles. In the setting of ongoing virtual interviews, it may be preferable to adapt supplementary interview materials, such as those listed in the Table, to a virtual format. A virtual tour and electronic materials about the institution or city were commonly utilized by PDs to showcase their institution and region. A virtual social event was held by many programs in an attempt to create an environment for more casual interactions between candidates and current trainees and, in some cases, faculty. Most programs kept this event relatively short at 1 hour or less and utilized small groups in breakout rooms to facilitate conversation. If successful, this event may be a beneficial opportunity to assess candidate's interpersonal skills and “fit” with the culture of the program.

Although Zoom was the most commonly used platform, no PDs reported significant deleterious effects on their interview day owing to technical difficulties. In the current pandemic, virtual platforms are increasingly improving their ease of use and the public is becoming increasingly comfortable with using virtual platforms. Thus, any familiar platform is likely able to accommodate a virtual interview day. Programs demonstrated awareness of “virtual meeting fatigue”17 and most structured their interview day to 4 hours or less for the candidates. Although the optimal amount of time with the candidates is unknown, there is likely a threshold at which increasing the length of the interview day is no longer beneficial for a fatigued candidate or interviewer.

In addition, we identified that programs interviewed more candidates than previous in-person application cycles. This may have been in reaction to the uncertainty of an unanticipated transition to exclusive virtual interviews this year. However, the number of interviews offered by each program and the number of interviews completed by each candidate should be monitored for stability in future years. As with the length of the interview day, there is likely a threshold of the number of interviews completed by each program per fellowship position beyond which there is little additional benefit.

Research implications

Even after resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely that at least a component of virtual interviewing will persist across the spectrum of medical training programs. Thus, it is important for future research to focus on further refinement of the ideal approach to optimize candidate and PD abilities to gather necessary information to make informed decisions. The ideal length of the interviews and interview day, the use and format of a virtual social event, and type and format of supplementary materials can all be further evaluated and optimized. Innovative strategies may be needed to improve the process for both candidates and programs. The potential use of a hybrid model of virtual and in-person interviews may also be considered and evaluated. When creating a hybrid model, careful consideration must be given to ensure the process is fair and equitable for all candidates.

Future research should follow up on the long-term outcomes after this virtual interview cycle to assess PDs concerns about the ability to present their program virtually and to assess whether the candidate is “fit” virtually. It will be important to evaluate if the candidate's actual experience in the program matches how it was presented virtually compared with the experience of their cofellows who interviewed in-person. Similarly, it will be important to evaluate whether the PDs’ perception of the “fit” of the candidate with their program was as accurate as previous in-person interview cycles.

Strengths and limitations

Our survey is strengthened by the excellent response rate from PDs. We also sent the survey in a time window when all programs had completed their interviews and submitted a rank list, but before the match results were made available. This allowed for the PDs to reflect solely on the recent virtual interview process without being biased by the results of the match. However, this is also a limitation of the survey because we were unable to collect data on the match outcome and whether this differed from previous years for each PD.

We also intentionally did not collect demographic data such as length of PD tenure, size of program, or location. This reduces bias in the interpretation of the results and any potential recommendations that may be made by the SMFM for approach to future interview cycles based on these data. This allows for each PDs response and desire for future years to be considered equally and the committee cannot be biased toward the response of more experienced PDs, larger programs, or more urban vs rural locations.

Finally, our survey was limited to only our individual subspecialty. However, because the virtual interview process is similar regardless of the specific training program, these data may be helpful to guide specialty and subspecialty training programs from all areas of graduate medical education in their approach to virtual interviews.

Conclusions

This study provides a thorough assessment of the PD experience with the unanticipated 2020 virtual interview process for MFM fellowship training programs. Given the circumstances, it is encouraging that most PDs found the experience satisfactory. There is interest among PDs in moving forward with a component of virtual interviews in the future. These data can help to guide creation of potential innovative, streamlined interview processes. In addition, these experiences may be useful outside of the MFM community to guide the approach to future virtual interview cycles in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The Research Electronic Data Capture data capture tool was funded by the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research grant support (Clinical and Translational Science Award program, through the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002373).

Cite this article as: Rhoades JS, Ramsey PS, Metz TD, et al. Maternal-fetal medicine program director experience of exclusive virtual interviewing during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;XX:x.ex–x.ex.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100344.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Frishman GN, Bell CL, Botros S, et al. Applying to subspecialty fellowship: clarifying the confusion and conflicts! Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah SK, Arora S, Skipper B, Kalishman S, Timm TC, Smith AY. Randomized evaluation of a web based interview process for urology resident selection. J Urol. 2012;187:1380–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandler NM, Litz CN, Chang HL, Danielson PD. Efficacy of videoconference interviews in the pediatric surgery match. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson SL, Hollis RH, Oladeji L, Xu S, Porterfield JR, Ponce BA. The burden of the fellowship interview process on general surgery residents and programs. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gressel GM, Van Arsdale A, Dioun SM, Goldberg GL, Nevadunsky NS. The gynecologic oncology fellowship interview process: challenges and potential areas for improvement. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;20:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerfoot BP, Asher KP, McCullough DL. Financial and educational costs of the residency interview process for urology applicants. Urology. 2008;71:990–994. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polacco MA, Lally J, Walls A, Harrold LR, Malekzadeh S, Chen EY. Digging into debt: the financial burden associated with the otolaryngology match. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156:1091–1096. doi: 10.1177/0194599816686538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner AK, Smink DS, Scott BG, Korndorffer JR, Harrington D, Ritter EM. How much are we spending on resident selection? J Surg Educ. 2018;75:e85–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee . NRMP Program Director Survey; Washington, DC: 2018. Results of the 2018. National Resident Matching Program. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menhaji K, Gaigbe-Togbe BH, Hardart A, et al. Virtual interviews during COVID-19: perspectives of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery program directors. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000982. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majumder A, Eckhouse SR, Brunt LM, et al. Initial experience with a virtual platform for advanced gastrointestinal minimally invasive surgery fellowship interviews. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231:670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.08.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewit R, Gosain A. Virtual interviews may fall short for pediatric surgery fellowships: lessons learned from COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2. J Surg Res. 2021;259:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vining CC, Eng OS, Hogg ME, et al. Virtual surgical fellowship recruitment during COVID-19 and its implications for resident/fellow recruitment in the future. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:911–915. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08623-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamba R, Bhagat N, Tran PC, Westrick E, Hassanein AH, Wooden WA. Virtual interviews for the independent plastic surgery match: a modern convenience or a modern misrepresentation? J Surg Educ. 2021;78:612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J. Psychiatric Times. 2020. A Neuropsychological exploration of Zoom fatigue.https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychological-exploration-zoom-fatigue Available at: Accessed January 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.