Abstract

Residues in surface water of ribavirin, which used extensively during the COVID-19 pandemic, have become an emerging issue due to its adverse impact on the environment and human health. UV/H2O2 and UV/peroxydisulfate (PDS) have different degradation effects on ribavirin, and the same operational parameter have different effects on the two processes. In this study, the reaction mechanism and degradation efficiency for ribavirin were studied to compare the differences under UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS processes. We calculated the total rate constants of ribavirin with HO• and SO4•- in the liquid phase as 2.73 × 108 and 9.39 × 105 M−1s−1. The density functional theory (DFT) calculation results showed that HO• and SO4•- react more readily with ribavirin via H-abstraction (HAA). The nitrogen-containing heterocyclic ring is difficult to undergo ring-opening degradation. The UV/PDS process was more stable and performed better than the UV/H2O2 for the ribavirin degradation when the same molar oxidant dosage was applied. HO• plays an extremely important role in the degradation of ribavirin by UV/PDS. The reason for this phenomenon is the combination of the higher yield of HO• produced in the UV/PDS process and the faster reaction rate of ribavirin with HO•. The UV/H2O2 process is more sensitive to pH than UV/PDS. Alkaline condition can significantly inhibit the ribavirin degradation. The effects of natural organic matter (NOM) and ribavirin concentration were also compared. Eventually, the toxicity prediction of the product showed that the opening-ring products were more toxic than the parent compound.

Keywords: Ribavirin, HO• and SO4•-, Degradation mechanism, Degradation efficiency, Aquatic toxicity

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-2019), a highly contagious disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is rapidly sweeping the world [1], [2]. With the deepening of the understanding of the virus, the treatment plan of COVID-19 is also constantly being adjusted [3], [4], [5]. Among them, ribavirin occupies a major position in the list of potential COVID-19 treatments in the fifth edition of the New Coronavirus Infected Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Plan [6].

Ribavirin, 1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide, is a synthetic riboside analogue. It blocks the replication of viruses on a large scale, thereby affecting their activity [7]. The consumption of ribavirin would have sharply increased during this period. However, drugs that enter the body are usually excreted in unaltered form and their metabolites [8], which leads to their continued presence in a (highly) bioactive form in the environment [9]. The predicted removal efficiency of ribavirin at traditional WWTPs was less than 2% [8]. So ribavirin has higher detection frequency and concentrations than historically reported [10]. As previously reported [11], [12], [13], ribavirin was detected in the influent and effluent water of the sewage treatment plant at concentrations close to 20 ng/L. Ribavirin was detected in the sediment in both summer and winter with a detection frequency of 100% in Wuhan, China [10]. Ribavirin in the environment has become an emerging problem which may cause toxicity to the organisms [8]. The resistance strains will be cultured if both the antiviral drug and the virus are present in the water [14].

It is imperative to use more effective technologies to remove ribavirin. UV-based advanced oxidant processes (AOPs) use UV irradiation combined with oxidants to produce highly active and strong oxidizing free radicals, which are widely used in the removal of refractory micro-pollutants [16], [17], [15]. UV/H2O2 is one of the most conventional AOPs, through H2O2 photolysis to produce hydroxyl radical (HO•) [18], [19]. HO• can nonselectively oxidize a series of pollutants [20]. Recently, the application of UV/PDS that can produce SO4 •- for micro-pollutant degradation has been getting considerable attention [21], [22]. Compared with HO• (E 0 =1.9–2.7 V) [23], SO4 •- has higher oxidation capacity (E 0 = 2.65–3.1 V) [24] and is selective and not disturbed by background organic matter, which can degrade containments in a wide range [25].

Despite the occurrence of ribavirin has attracted increasing research in the environment, there is a lack of available knowledge about the degradation mechanism of ribavirin. Research on the reactivity of ribavirin towards two radicals (HO• and SO4 •-) was still limited. The differences in the active sites of ribavirin between HO• and SO4 •- are largely unknown. The degradation efficiency of ribavirin between different environmental conditions is far less explored to date. pH value is the key variable affecting the concentrations of HO• and SO4 •- in the UV/PDS process [26]. Because SO4 •- can be converted to HO• to some extent, and this process depends on the pH in the reaction environment [27]. To explain the above differences, the radical involvement and underlying mechanisms in the process should be addressed. NOM is considered as a typical radical scavenger [28], [29], its scavenging effect on different AOPs needs systematic investigation. Due to from a toxicity perspective, pollutants may form new highly toxic products with potentially adverse effects on the environment [30]. So it is urgent to evaluate the pollution levels of products.

To fill these gaps, the objectives of this work are to study two AOPs (UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS) for the degradation of ribavirin in the water environment, with great emphasis on the activity difference of two free radicals (HO• and SO4 •-), the degradation mechanism, the influence of environmental conditions and toxicity evaluation. Firstly, the degradation kinetics of the ribavirin with HO• and SO4 •- were comparatively calculated; then, the active sites of the ribavirin were revealed based on DFT. Furthermore, the degradation pathways and products of ribavirin in aqueous solution were proposed. In addition, the effects of the operating parameters (such as pH, NOM, oxidant and pollutant concentrations) on the degradation behaviors in UV/PDS and UV/H2O2 were evaluated. Especially, we differentiated the contributions of responsible radicals (HO• and SO4 •-) to the degradation in UV/PDS process in this paper. Finally, the toxicity of the products was predicted, divided and evaluated.

2. Method

2.1. Quantum chemical calculations

In this study, Gaussian 16 software [31] was used to carry out the theoretical calculation based on the DFT. The 6–31 +G(d,p) basis set and M06–2X functional were selected to optimize the geometric structures (including reactants, intermediates, transition states and products), which has been proven to be suitable and successfully used in numerous studies [32], [33]. To obtain accurate energy parameters, the single point energies of all compounds were calculated at the M06–2X/6–311 + +G(3df,2p) level. By the calculation of vibration frequency, the structure can be judged as true minimum and stationary point. The vibration frequencies of both reactants and products are positive, and only the transition state has a virtual frequency. In addition, the calculation of intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) confirmed that the transition state correctly connects the reactant and product [34]. Since the process of simulation is in water environment, the solvation effect is taken into account. Of all the calculations, the solvation model (SMD) using water as the solvent and treating the solvent environment as a polarizable continuous medium, was used to evaluate the solvent effect [35]. HO• and SO4 •- react with ribavirin mainly through three underlying reaction mechanisms: single electron transfer (SET), H-atom abstraction (HAA) and radical addition (RAF). The changes of free energy (ΔG ‡) and Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of SET reaction were calculated through Marcus theory. More detailed calculations of the reaction mechanism are shown in Supporting Information (SI).

2.2. Rate constant calculations

The transition state theory (TST) [36] was used to calculate the reaction rate constants of ribavirin with HO• and SO4 •-. In order to simulate the aquatic environment as much as possible, the diffusion efficiency was taken into account. The calculation of the apparent rate constant was combined with the solvent cage effect [37]. Detailed calculations are shown in SI.

2.3. Degradation efficiency calculations

Kintecus 6.50 software package [38] was used to simulate the influence of environmental factors, which has been proved to be feasible and successfully applied to the calculation of degradation efficiency of various AOPs [39], [40]. We set the initial pollutant and oxidants with the different concentrations in the ranges of 0.1–100 μM and 10–250 μM to study their influence on the degradation efficiency. Phosphate buffer solution (0.005 M) regulates the pH values of the simulated ultrapure solution in the range of 3–9.5. The influence of NOM in the concentration range of 0.1–100 μM on degradation efficiency was also simulated. All reactions involved in Kintecus software simulation and their rate constants are shown in Tables S5 and S6.

2.4. Toxicity assessment

Computerized Ecological Structure Activity Relationships model software (ECOSAR) [41] and Toxicity Estimation Software Tool [42] were used to predict the toxicity and health effects of ribavirin and its products, which have been widely used as effective-predictive tools [43]. The acute and chronic toxicity of ribavirin and its products to aquatic organisms with different nutrient levels (green algae, Daphnia and fish) was evaluated by simulating maximum median effect concentration (EC50) or lethal concentration (LC50) and chronic toxicity value (ChV). Human health effects included developmental toxicity and mutagenicity on health toxicology.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. HO• and SO4•-- initiated reaction of ribavirin

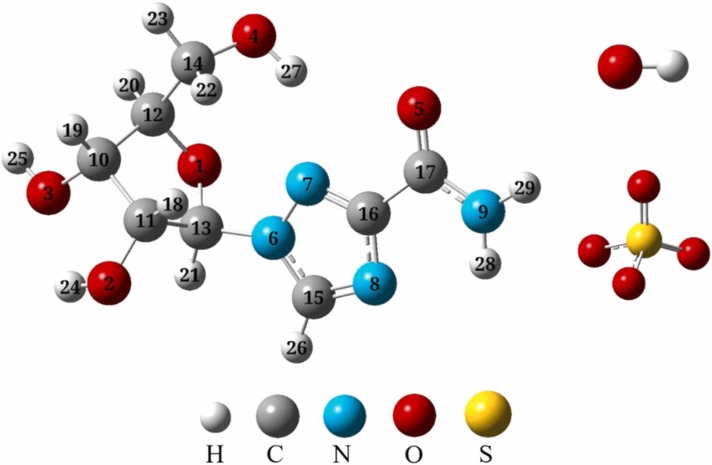

The structure of ribavirin is rather complex as shown in Fig. 1, which has acyl amine, hydroxyl, two five-membered heterocyclic rings containing nitrogen and oxygen. HO• and SO4 •- react with organic pollutant typically via three competing pathways: HAA, RAF and SET [44]. HO• and SO4 •- can react with unsaturated bonds to form free radical adducts. In this study, 12 H-abstraction and SET paths (see Figs. S1) and 5 addition channels (see Fig. 3) were analyzed in detail. ΔG ‡ and ΔG are used to judge the difficulty of each reaction together. To better show the comparison, we plot the results of HAA and RAF by HO• and SO4 •- in a potential energy profile together (see Fig. 2 and S2).

Fig. 1.

The optimized stable geometries of ribavirin, HO• and SO4•- at M06–2X/6–31+g(d,p) level.

Fig. 3.

Detailed reaction paths of RAF of ribavirin initiated by HO• (red) and SO4•- (blue) with ∆G‡ and ∆G. All units of value are kcal mol−1.

Fig. 2.

Potential energy profile of HAA of ribavirin initiated by HO• (left) and SO4•- (right).

3.1.1. Single electron transfer

The ΔG ‡ and ΔG of the SET between ribavirin and HO•, SO4 •- are 26.74 and 30.59 kcal mol−1, 13.31 and 27.71 kcal mol−1, respectively. SO4 •- is a strong oxidizing radical, which prefers to react with nucleophile structures via single electron transfer [45]. Ribavirin structure contains electron-donating functional groups (-OH, -NH2), which are more likely to have single electron transfer reaction with SO4 •-. Therefore, compared with hydroxyl radicals, the ΔG ‡ and ΔG of SET between ribavirin and SO4 •- are lower, which is consistent with our calculation results. However, the single electron transfer reaction between ribavirin and SO4 •- is an endothermic reaction (ΔG = 27.71 kcal mol−1), which is difficult to undergo spontaneous reaction at room temperature.

3.1.2. H-abstraction

A total of 12 H atoms on ribavirin, including five-membered heterocyclic rings, acyl amine and hydroxyl, can be attacked by HO• and SO4 •- through HAA. The ΔG ‡ and ΔG of HAA on the five-member oxygen ring and its branched chain by HO• (6.41 ∼ 15.57 kcal mol−1, −26.92 ∼ −8.91 kcal mol−1) is lower than SO4 •- (9.90 ∼ 19.54 kcal mol−1, −17.53 ∼ 0.47 kcal mol−1). Similarly, the ΔG ‡ and ΔG of HAA on the five-member nitrogen ring and its branched chain by HO• (17.34 ∼ 17.87 kcal mol−1, −4.39 ∼ 0.53 kcal mol−1) is lower than SO4 •- (26.43 ∼ 34.16 kcal mol−1, 4.99 ∼ 9.92 kcal mol−1). These results indicate ribavirin is more prone to HAA with HO• rather than SO4 •-. Especially, it can be seen from Fig. S1 that the energy barrier and reaction heat of the HAA between containing nitrogen heterocycle and HO•, SO4 •- are higher, especially for SO4 •-. It means that in the whole structure of ribavirin, the nitrogen-containing heterocyclic ring is the most difficult to undergo ring-opening degradation. It also clearly explains the reason that structure of nitrogen-containing heterocycles is often found in the degradation products of ribavirin [12], [46].

3.1.3. Free radical addition

Five addition reaction pathways are calculated based on the reaction of HO• and SO4 •- with two unsaturated bonds (C O and C N) of ribavirin. The ΔG ‡ and ΔG of RAF by HO• (12.44 ∼ 39.79 kcal mol−1, −15.60 ∼ 43.91 kcal mol−1) are lower than SO4 •- (15.46 ∼ 53.27 kcal mol−1, −2.70 ∼ 54.13 kcal mol−1), which indicates ribavirin is more prone to react with HO• rather than SO4 •-. In addition, compared with HAA, the values of ΔG ‡ and ΔG about RAF are much higher. It indicates that HAA is more likely take place than the RAF. As shown in Fig. 3, R17a and R17b have the highest energy barrier (39.79 and 53.27 kcal mol−1, respectively) and require a lot of heat to occur (43.91 and 54.13 kcal mol−1, respectively). It means that Site 8 in the ribavirin is resistant to attack by hydroxyl and sulfate radicals and is structurally stable. The R16a and R16b have the lowest energy barrier (12.44 and 15.46 kcal mol−1, respectively) and are endothermic reactions. According to the calculation results, among all unsaturated bonds containing nitrogen heterocycles, the carbon sites (Site 15 and 16) in the double bonds (N = C) are more readily to be attacked by HO• and SO4 •-, resulting in RAF. On the contrary, the nitrogen sites (Site 7 and 8) in the double bond (C N) are difficult to undergo RAF, and the energy barrier is higher than 25 kcal mol−1. Comparing the ΔG ‡ and ΔG of all reaction paths, the results show that the energy barrier of HO•-initiated abstraction reaction is the lowest, especially R2a, R5a and R9a, which are also exothermic reactions. From the perspective of thermodynamics, these paths (R2a, R5a and R9a) are most readily to occur, and their intermediates (IM2, IM5, IM9) play an important role in the subsequent reactions.

3.2. Rate constants

To clarify the effect of each initial reaction pathway on the total reactions and determine the optimal reaction path, we calculated the variation of rate constant and its branching ratio in the range of 278–320 K for each initial reaction. Since the simulated reaction condition is in the liquid phase, the effect of diffusion in water on the reaction rate constant was fully considered during the calculation process. The values of rate constants and branching ratios for each initial reaction path are shown in Tables S1 and S2.

In the liquid phase, it was calculated that the total rate constants of the initial reactions initiated by HO• and SO4 •- at 298 K were 2.73 × 108 and 9.39 × 105 M−1s−1, respectively. The total rate constants of ribavirin with HO• is 2 orders of magnitude higher than with SO4 •-, meaning that ribavirin is more susceptible to be attacked by HO•. In the initial reaction of ribavirin with HO•, the rate constants and branching ratios of HAA, RAF and SET are 2.73 × 108 M−1s−1 and 100%, 6.31 × 103 M−1s−1 and 0.00%, 1.28 × 10−7 M−1s−1 and 0.00%, respectively. The reasons for this result include two parts, one is that the reaction rate constant of the HAA is the highest, and the other is that the number of HAA paths is more than the RAF. In the initial reaction of ribavirin with SO4 •-, the rate constants and branching ratios of HAA, RAF and SET are 9.38 × 105 M−1s−1 and 99.89%, 3.44 × 101 M−1s−1 and 0.00%, 9.87 × 102 M−1s−1 and 0.11%, respectively. The cause of this result is the same as that of HO•.

The paths with a value of lgk greater than zero are summarized and plotted in Figs. S3a and b. The contribution degree of each path to the total initial reaction can be seen intuitively from the figures, and each path has obvious differences. As shown in Fig. S3a, four paths, including R2a, R5a, R7a and R9a, with lgk values are greater than 7. The HAA with the highest branch ratio is R5a (59.11%), followed by R2a (22.67%) and R9a (10.93%). R5a, R2a and R9a account for 93% of the total rate constant and play a vital role in determining the initial reaction. As shown in Fig. S3b, among all the SO4 •--initial reactions, only R4b has a lgk value greater than 5. R4b is the decisive step of the initial reaction, which accounts for 85% of the total rate constant. Therefore, only the reaction paths and their intermediates that contribute significantly to the reaction are discussed in the subsequent studies. These calculation results indicate that R2a, R5a and R9a are the vital reaction channels, and IM2, IM5, IM9 are main intermediates.

From the perspective of the practical application of AOPs in the environment, we investigate the variation of the rate constant over the temperature range 278–320 K. And we set the temperature gradient as: 278 K, 285 K, 292 K, 298 K, 306 K, 313 K and 320 K. As shown in Fig. 4, as the temperature increases, the rate constant increases with a positive correlation. The variation trends of the HAA and the total reaction basically coincide, indicating that when the temperature changes, HAA is still the decisive path of the reaction. In addition, it can be calculated from the specific data in Tables S3 and S4 that with temperatures ranging from 278 K to 320 K, the HO•-initiated k abs and k total increase by 5 times and k add increases by 21 times. The SO4 •--initiated k abs and k total increase by 11 times and k add increases by 43 times. Although RAF is more sensitive to the change of temperature, the rate constant of RAF is still low and does not have a significant effect on the total rate constant. In addition, we found that compared with HO•-initiated, the SO4 •--initiated rate constant increased more obviously. Compared with the HAA, the RAF has a more significant trend with temperature, especially the SO4 •--addition. We think it depends on the endothermic and exothermic conditions of the reaction. Hydroxyl-induced hydrogen extraction reactions are mostly exothermic reactions, but SO4 •--initial abstraction reactions contain partial endothermic reactions. In addition, the RAF is basically an endothermic reaction, especially SO4 •--initial addition. Therefore, we have the conclusion that endothermic reactions are more sensitive to temperature changes and are easily affected by ambient temperature.

Fig. 4.

The changes of rate constant of HO•-initiated (blue) and SO4•--initiated (yellow) HAA, RAF and total reaction with temperature from 280 to 320 K.

3.3. Subsequent reactions

From thermodynamic and kinetic point of view, R2a, R5a and R9a have the low energy barrier and the high reaction rate constant, which are the main reaction channels. IM2, IM5 and IM9 are the vital intermediates, which are selected to conduct subsequent studies. O2, HO2 •, etc. are still present in AOPs and aquatic environments which could continue to react with major intermediates (IM2, IM5 and IM9) for degradation. Associated degradation pathways are shown in Figs. S4–6.

3.3.1. Further conversion reactions of IM2

The subsequent reactions of IM2 mainly include branching chain breaking, ring-opening and aldehyde. IM2 has an intramolecular hydrogen transfer reaction. The H on C atom in the IM2–1 generated comes from the transfer of hydrogen from the terminal oxygen atom. Subsequently, branch chain (-CH2) fracture occurs, which is an exothermic reaction (ΔG = −5.35 kcal mol−1) with a lower energy barrier (ΔG ‡ = 3.40 kcal mol−1). The formation of the P1 is supplemented by hydrogen supplied by H2O or HO2 •. Taking H-atom off of HO2 • and adding it into IM2–2 requires overcoming the energy barrier of 25.99 kcal mol−1 and releasing the energy of 38.11 kcal mol−1. In contrast, the reaction to take H-atom away from H2O is more difficult, requiring high barrier and large amount of heat (ΔG ‡ = 32.67 kcal mol−1, ΔG = 26.88 kcal mol−1). O2 can also undergo HAA form P2, which needs to overcome the energy barrier of 4.53 kcal mol−1 and is an exothermic reaction. IM2 needs to overcome energy barrier of 15.38 and 24.35 kcal mol−1, respectively, to form ring-opening intermediates (IM2–3 and IM2–4). IM2–3 reacting with HO• is a barrierless and exothermic reaction, producing P3. IM2–4 can react with O2 undergoing HAA to form P4.

3.3.2. Further conversion reactions of IM5

P6 and P7 can be formed through various paths. IM5 readily reacts with hydroxyl groups in water without barriers, combining to form P5, and this process releases a lot of heat. Subsequently, P5 is converted to P6 by undergoing intramolecular dehydration reaction. P6 can also be formed by the reaction of oxygen absorbing hydrogen from IM2, which has a lower energy barrier and is exothermic. HO• could continue to attack P6 and generate IM5–1 through HAA. IM5–1 as a primary intermediate, could produce P7 through two paths. IM5–1 could react with O2 to produce peroxyradical compound IM5–2. After the bond fracturing in IM5–2, HO2 • is removed and P7 is generated. P7 can also be formed by the reaction of oxygen taking hydrogen from IM5–1, which has a lower energy barrier (ΔG ‡ = 9.34 kcal mol−1). We tried to break the N-C bond, but after calculation, we found that this process has a high energy barrier and needs to absorb a lot of heat (ΔG ‡ = 36.56 kcal mol−1, ΔG = 33.06 kcal mol−1), which is generally considered difficult to occur in the liquid phase. The bond of N and C is stability. IM5 can also undergo ring-opening reaction of five-membered rings containing oxygen, resulting in IM5–5 and IM5–6. IM5–5 easily reacts with hydroxyl groups to form stable compounds P8. IM5–6 generates hydroxylation product P10 through a barrierless reaction with HO•. Subsequently, P11 is formed through intramolecular dehydration reaction under the action of water bridge. In addition, O2 can directly capture H-atom on C to form aldehyde compounds P11. IM5 also breaks the bonds (-CH2OH) to form P9.

3.3.3. Further conversion reactions of IM9

The subsequent reaction of IM9 is mainly ring-opening degradation. IM9 can be ring-opened at two different sites of oxygen-containing five-membered rings to form IM9–1 and IM9–2. O2 reacts with IM9–1 taking H-atom away from –OH, resulting in aldehyde, which overcomes low energy barrier and is exothermic reaction (ΔG ‡ = 5.17 kcal mol−1, ΔG = −22.48 kcal mol−1). IM9–2 can rapidly react with HO• to product P13. In addition, IM9–2 can undergo an intramolecular hydrogen transfer reaction to generate IM9–3. Subsequently, O2 plays the role of oxidation and aldehyde stable product P14 is generated by HAA. IM9 can be ring-opened at two different sites of oxygen-containing five-membered rings to form IM9–4 and IM9–5. However, the formation of IM9–5 needs to overcome 44.52 kcal mol−1 energy barrier and absorb a lot of heat (ΔG = 42.70 kcal mol−1), which is hardly take place in the water at room temperature. IM9–4 can use two compounds (H2O and HO2 •) to add H-atom. By comparing the calculated results, H-atom is more easily provided by HO2 •, which is an exothermic reaction. The reaction of H-atom supplied by H2O requires the absorption of large amounts of heat (ΔG = 28.03 kcal mol−1), which is difficult to occur in a natural water environment. Direct aromatic ring-opening reaction occurs with difficulty.

3.4. Effect of environmental parameters on degradation efficiency

Hydroxyl and sulfate radical are the key radicals of ribavirin degradation under UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS processes. The production and action of these free radicals are sensitive to environmental changes. Treatment times, initial pollutant concentration and oxidant dosages are the primary parameters affecting degradation efficiency of target pollutant [47]. pH may enhance or inhibit the formation of reactive radicals. In addition, NOM significant restrained the degradation of ribavirin by the different processes through scavenging radicals such as HO• and SO4 •-. The purpose of this subsection was to elucidate the specific differences of ribavirin degradation behavior and related triggering factors of various water matrix components (oxidant, pollutant, pH, NOM). In addition, experiments proved that ribavirin and other drugs were stable under ultraviolet irradiation [48]. Based on this, we only studied the oxidative degradation of ribavirin by free radicals in this paper.

3.4.1. Effect of treatment times

As shown in Fig. 5a, the time evolution profiles of the ribavirin degradation (1 μM) in the presence of H2O2/PDS (200 μM) at pH 7. In general, more free radicals are produced and the degradation efficiency increases gradually with the treatment times. As the results showed that more appreciable degradation of ribavirin was achieved under UV/PDS than UV/H2O2. In addition, different processes have different increasing trends over time. When the reaction time reaches 60 min, the degradation efficiency of UV/PDS process has reached 90%, and the improvement trend of UV/PDS process is not as good as before.

Fig. 5.

Degradation efficiency of ribavirin under different conditions in UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS. (a) Effect of treatment time ([ribavirin] = 1 μM; pH = 7; [oxidant] = 200 μM), (b) effect of oxidant concentration ([ribavirin] = 1 μM; pH = 7; t = 60 min), (c) effect of initial ribavirin concentration ([oxidant] = 200 μM; pH = 7; t = 60 min), (d) effect of NOM ([ribavirin]= 1 μM; [oxidant] = 200 μM; pH = 7; t = 60 min).

3.4.2. Effect of oxidant dosages

As shown in Fig. 5b, the effect of oxidant (H2O2 and PDS) dosages on the ribavirin degradation efficiency by the UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS processes. The degradation efficiency of ribavirin increased significantly from 33% to 71%, 45–93% with increasing oxidant dosage from 10 to 250 μM in the UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS processes, respectively (see Tables S7 and S8). As shown in Fig. 5b, HO• is the primary radical to oxidize the ribavirin rather than SO4 •- in the UV/PDS process. The reason for this phenomenon is the combination of the higher concentration of HO• produced in UV/PDS process and the faster reaction rate of ribavirin with HO•. Interestingly, the degradation efficiency of ribavirin changed slowly with an increasing oxidant (H2O2 and PDS) dosages from 150 to 250 μM. When the degradation efficiency of UV/PDS process reaches 90%, the degradation efficiency cannot be greatly improved by adding oxidant. It is mainly because the concentration of free radicals is high but the concentration of substrate is relatively insufficient. In addition, the same phenomenon was found in the UV/H2O2 process. When the degradation efficiency of UV/H2O2 process reaches ∼ 70%, the degradation efficiency cannot be greatly improved. In theory, hydroxyl also reacts with H2O2. The addition of excessive oxidant turns H2O2 into a free radical scavenger that competes with contaminants.

3.4.3. Effect of initial pollutant

As shown in Fig. 5c, the degradation efficiency is negatively correlated with the concentration of ribavirin. When the concentration of pollutant is less than 1 μM, the increase of initial pollutant does not cause significant change of degradation efficiency. When the pollutant concentration is greater than 1 μM, the degradation efficiency shows a downward trend. Especially, when the pollutant concentration is above 10 μM, the degradation efficiency decreases rapidly. This is mainly because the production of HO• and SO4 •- at the outset is sufficient to efficiently degrade ribavirin. As the concentration of ribavirin increases, free radicals not only need to degrade pollutants but also need to degrade the oxidative by-products of ribavirin, so the concentration of free radicals is particularly insufficient.

3.4.4. Effect of NOM

As shown in Fig. 5d, NOM could retarde the degradation of ribavirin. And the decrease in degradation efficiency for ribavirin increased with the increasing NOM concentration under UV/ H2O2 and UV/PDS. When the concentration of NOM is less than 1 μM, the degradation efficiency of ribavirin is maintained at about 90% without obvious change (see Tables S7 and S8). However, as the concentration of NOM is greater than 10 μM, NOM makes a huge contribution to the scavenging of HO• and SO4 •-, the degradation efficiency for ribavirin reduced from 70% and 93–20% and 24% under UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS, respectively. Meanwhile, NOM also could scavenge SO4 •- under UV/PDS [49]. Meanwhile, the scavenging effect of NOM on SO4 •- was also significant [50], [51]. But based on our calculations, we found the contribution of sulfate radicals to the degradation of ribavirin is slightly increased from 0.03% to 0.06%. The reason for this phenomenon is that SO4 •- contributes less to the degradation of ribavirin and the concentration of SO4 •- produced in the UV/PDS process is less than that of hydroxyl groups. Judging from these results, it indicates that NOM is the major HO• and SO4 •- scavenger and can significantly inhibit the degradation of ribavirin during UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS processes.

3.4.5. Effect of pH

As shown in Fig. 6a, the effect of pH on degradation efficiency varies significantly depending on the various processes. For UV/H2O2, the best degradation condition of ribavirin is observed under acidic conditions. Furthermore, under alkaline conditions, with the increase of pH, the degradation efficiency decreased from 70% to 26%, showing a significant downward trend. It means that under acidic conditions, H2O2 is more likely to produce hydroxyl groups. Interestingly, we found different degradation efficiency trends with pH in the UV/PDS process. For UV/PDS, its degradation efficiency is less affected by pH, and the degradation efficiency under acidic, neutral and alkaline conditions is maintained at a stable level of 90%. The degradation efficiency decreased slightly in the range of pH from 6 to 8, which is agreed with the previous study [52], [53] but different from the work of Sbardella et al. Sbardella et al., ($year$) [54]. Such inconsistency may be explained by the property differences of the selected target compounds. The decrease in HO• concentration was primarily due to competing reactions involving other things. Under alkaline conditions, as pH continues to rise, the degradation efficiency shows an increasing trend. To explore the rationale, we compared hydroxyl concentration under different pH conditions. As shown in Fig. 6b, the HO• concentration decreased sharply from acidic to alkaline conditions under UV/H2O2. On the contrary, from acidic to alkaline conditions, HO• concentration is basically maintained under UV/PDS, unlike the violent decline in the UV/H2O2 process. In the UV/PDS process, as alkalinity increases, the concentration of hydroxyl groups increases. This is mainly due to the concentration of HO• with the increase of alkalinity, and HO- can react with SO4 •- to generate HO• and promote the degradation of pollutants. Results demonstrate that the UV/H2O2 process is highly sensitive to pH. The UV/PDS process is not sensitive to pH and can be applied in a wide pH range.

Fig. 6.

Degradation efficiency and HO• concentration under different pH in UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS processes ([ribavirin] = 1 μM; [oxidant] = 200 μM; t = 60 min).

3.5. Toxicity assessment

ECOSAR and T.E.S.T. are selected to conduct the toxicity prediction of ribavirin and products, which are convenient and rapid, allowing for initial screening for toxicity. In this study, the toxicity assessment focuses on the harm to aquatic ecology and the threat to human health.

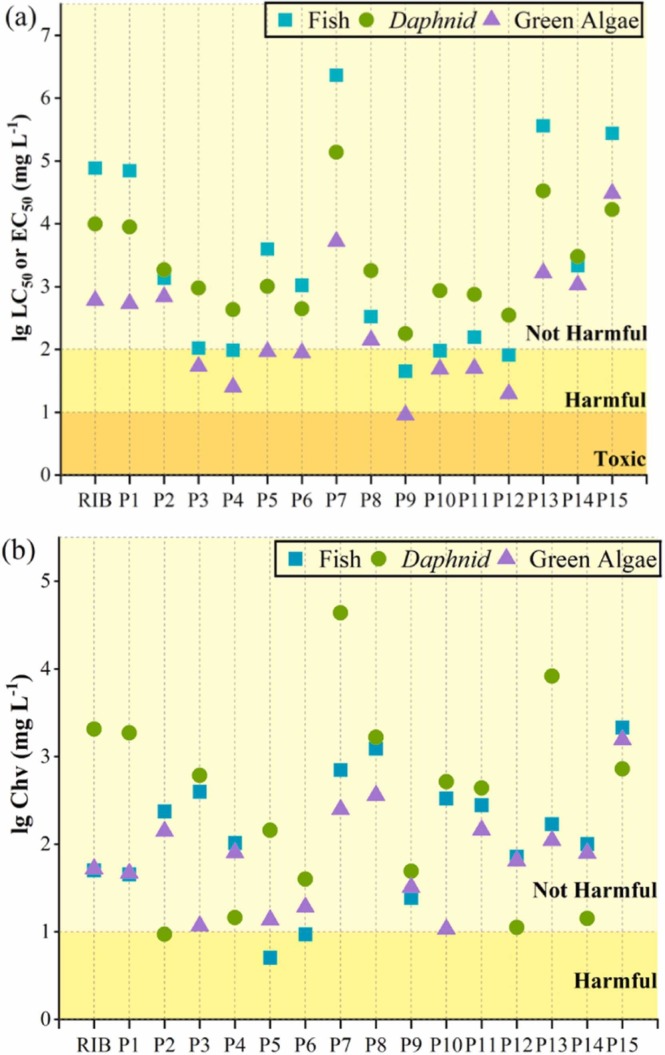

3.5.1. Acute and chronic toxicities to aquatic organisms

The toxicity values of oxidation products and the toxicity evaluation criteria are listed in Tables S10 and S11, respectively. According to the toxicity classification standards developed by the European Union, the predicted LC50 or EC50 values of ribavirin on fish, Daphnia and green algae are 7.71 × 104, 9.93 × 103 and 6.01 × 102 mg L−1, which are all classified as not harmful. The Chv of ribavirin on fish, Daphnia and green algae are 5.03 × 101, 2.06 × 103 and 5.23 × 101 mg L−1, which are also classified as not harmful. Although ribavirin has no toxicity to fish, Daphnia and green algae, it may accelerate the establishment of antiviral drug resistance. So the degradation of ribavirin is necessary, we also need to pay attention to the changes of toxicity about products. As shown in Fig. 7a, most of the products have toxicity to fish and green algae, but all of the products have no obviously acute toxicity to Daphnia. In detail, green algae are most sensitive to the products. The toxicity of P9 to green algae reached a toxic level. Interestingly, results show that the ring-opening products of oxygen-containing heterocycles (P3, P4, P10, P11, P12) and unsaturated oxygen-containing heterocycles (P9) are more likely to exhibit acute toxicity to green algae and fish. In terms of chronic toxicity, except for P2, P5 and P6, the rest of products are non-harmful to aquatic organisms.

Fig. 7.

Acute and chronic toxicities of ribavirin and products to three aquatic organisms.

3.5.2. Mutagenicity and developmental toxicity

Based on the predicted results, ribavirin has development toxicity and no mutagenicity (see Fig. S7). Except for P2, most of the products still have developmental toxicity. As the reaction progressed, some products (P1, P3, P9 and P10) showed obvious developmental toxicity, and P1 was commonly detected in the experiment [12]. Therefore, ribavirin degradation products need to be tracked and detected in the future for further degradation.

4. Conclusions

The thermodynamic and kinetic of the degradation of ribavirin initiated by HO• and SO4 •- were systemically studied in this paper. We also simulated the subsequent reactions of primary intermediates with HO•, O2 and HO2 • in aqueous. The differences of degradation mechanism and degradation efficiency of ribavirin caused by environmental parameters between two AOPs (UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS) were compared. The toxicity of the products was predicted to comprehensively evaluated the degradation of ribavirin. The findings showed:

-

(1)

The main reaction method of ribavirin with HO• and SO4 •- is H-abstraction reaction. The main attacked reaction sites are on the oxygen-containing heterocycle and its branched chains. The total rate constants between ribavirin and HO•, SO4 •- are 2.73 × 108 and 9.39 × 105 M−1s−1 at 298 K, respectively, which means the reactivity of HO• toward ribavirin is higher than that of SO4 •-. Temperature has a positive correlation with the reaction rate constant.

-

(2)

When the same dose of H2O2 and PDS are applied, UV/PDS can degrade ribavirin more efficiently than UV/H2O2 due to the higher yield of HO•. Ribavirin degradation efficiency is negatively correlated with the ribavirin concentration and positively correlated with H2O2 and PDS dosage. NOM inhibits the removal of ribavirin as a free radical scavenger.

-

(3)

Acidic conditions facilitate the degradation of ribavirin by the UV/H2O2 process. Conversely, the UV/PDS process is not sensitive to pH and can be used over a wide range.

-

(4)

Most products of ribavirin, especially ring-opening products, are harmful to aquatic organisms such as green algae. The products still have developmental toxicity, and even some products have positive mutagenicity that requires our attention.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jinchan Jiang: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZeXiu An: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization. Mingxue Li: Investigation, Methodology. Yanru Huo: Formal analysis. Yuxin Zhou: Visualization. Ju Xie: Resources, Conceptualization. Maoxia He: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC No. 22276109, 21777087, 21876099).

Editor: Pei Xu

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jece.2022.109193.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Data Availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Le T., Andreadakis Z., Kumar A., Román R., Tollefsen S., Saville M., Mayhew S. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L., Liu S., Liu J., Zhang Z., Wan X., Huang B., Chen Y., Zhang Y. COVID-19: immunopathogenesis and immunotherapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:128. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jirjees F., Saad A.K., Al Hano Z., Hatahet T., Al Obaidi H., Dallal Bashi Y.H. COVID-19 treatment guidelines: do they really reflect best medical practices to manage the pandemic? Infect. Dis. Rep. 2021:13. doi: 10.3390/idr13020029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ying W., Qian Y., Kun Z. Drugs supply and pharmaceutical care management practices at a designated hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021;17:1978–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhai P., Ding Y., Wu X., Long J., Zhong Y., Li Y. The epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong W.-J., Zhou T., Wu S.-L., Ye J.-L., Xu J.-Q., Zeng F., Su Y.-Y., Han Y., Lv Y.-N., Zhang Y., Cai X.-F. A retrospective analysis of clinical efficacy of ribavirin in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021;27:876–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2021.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darwish I.A., Askal H.F., Khedr A.S., Mahmoud R.M. Stability-indicating thin-layer chromatographic method for quantitative determination of ribavirin. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2008;46:4–9. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/46.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuroda K., Li C., Dhangar K., Kumar M. Predicted occurrence, ecotoxicological risk and environmentally acquired resistance of antiviral drugs associated with COVID-19 in environmental waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;776 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nannou C., Ofrydopoulou A., Evgenidou E., Heath D., Heath E., Lambropoulou D. Antiviral drugs in aquatic environment and wastewater treatment plants: a review on occurrence, fate, removal and ecotoxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;699 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X., Lei L., Liu S., Han J., Li R., Men J., Li L., Wei L., Sheng Y., Yang L., Zhou B., Zhu L. Occurrence and risk assessment of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) against COVID-19 in lakes and WWTP-river-estuary system in Wuhan, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;792 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gani K.M., Hlongwa N., Abunama T., Kumari S., Bux F. Emerging contaminants in South African water environment- a critical review of their occurrence, sources and ecotoxicological risks. Chemosphere. 2021;269 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X., Hong Y., Ding S., Jin W., Dong S., Xiao R., Chu W. Transformation of antiviral ribavirin during ozone/PMS intensified disinfection amid COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;790 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng X., Wang C., Zhang K., Wang Z., Huang Q., Yu Y., Ou W. Profile and behavior of antiviral drugs in aquatic environments of the Pearl River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;466–467:755–761. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laughlin C., Schleif A., Heilman C.A. Addressing viral resistance through vaccines. Future Virol. 2015;10:1011–1022. doi: 10.2217/fvl.15.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao Z., Jia Y., Wang Q., Cheng H. High-efficiency photo-Fenton Fe/g-C3N4/kaolinite catalyst for tetracycline hydrochloride degradation. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021;212 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao L., Minakata D., Wei Z., Spinney R., Dionysiou D.D., Tang C.-J., Chai L., Xiao R. Mechanistic study on the role of soluble microbial products in sulfate radical-mediated degradation of pharmaceuticals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:342–353. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b05129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang J., Gong Y., An Z., Li M., Huo Y., Zhou Y., Jin Z., Xie J., He M. Theoretical investigation on degradation of DEET by •OH in aqueous solution: mechanism, kinetics, process optimization and toxicity evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;362 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenfeldt E.J., Linden K.G., Canonica S., von Gunten U. Comparison of the efficiency of OH radical formation during ozonation and the advanced oxidation processes O3/H2O2 and UV/H2O2. Water Res. 2006;40:3695–3704. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shad A., Chen J., Qu R., Dar A.A., Bin-Jumah M., Allam A.A., Wang Z. Degradation of sulfadimethoxine in phosphate buffer solution by UV alone, UV/PMS and UV/H2O2: kinetics, degradation products, and reaction pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;398 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao R., Noerpel M., Ling Luk H., Wei Z., Spinney R. Thermodynamic and kinetic study of ibuprofen with hydroxyl radical: a density functional theory approach. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2014;114:74–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jing B., Li J., Nie C., Zhou J., Li D., Ao Z. Flow line of density functional theory in heterogeneous persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes for pollutant degradation: a review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao R., Liu K., Bai L., Minakata D., Seo Y., Kaya Göktaş R., Dionysiou D.D., Tang C.-J., Wei Z., Spinney R. Inactivation of pathogenic microorganisms by sulfate radical: Present and future. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;371:222–232. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buxton G.V., Greenstock C.L., Helman W.P., Ross A.B. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (⋅OH/⋅O− in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1988;17:513–886. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neta P., Huie R.E., Ross A.B. Rate constants for reactions of inorganic radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1988;17:1027–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mei Q., Sun J., Han D., Wei B., An Z., Wang X., Xie J., Zhan J., He M. Sulfate and hydroxyl radicals-initiated degradation reaction on phenolic contaminants in the aqueous phase: mechanisms, kinetics and toxicity assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;373:668–676. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan R., Wang Z., Hu Y., Wang B., Gao S. Probing the radical chemistry in UV/persulfate-based saline wastewater treatment: kinetics modeling and byproducts identification. Chemosphere. 2014;109:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao Y., Zhang L., Zhang W., Lim K.-Y., Webster R.D., Lim T.-T. Comparative evaluation of iodoacids removal by UV/persulfate and UV/H2O2 processes. Water Res. 2016;102:629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakretz A., Ron E.Z., Harif T., Mamane H. Biofilm control in water by advanced oxidation process (AOP) pre-treatment: effect of natural organic matter (NOM) Water Sci. Technol. 2011;64:1876–1884. doi: 10.2166/wst.2011.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westerhoff P., Aiken G., Amy G., Debroux J. Relationships between the structure of natural organic matter and its reactivity towards molecular ozone and hydroxyl radicals. Water Res. 1999;33:2265–2276. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu W., Huang F., Liao Y., Zhang J., Ren G., Zhuang Z., Zhen J., Lin Z., Wang C. Treatment of CrVI-Containing Mg(OH)2 Nanowaste. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5619–5622. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Petersson, G.A., Nakatsuji, H., Li, X., Caricato, M., Marenich, A.V., Bloino, J., Janesko, B.G., Gomperts, R., Mennucci, B., Hratchian, H.P., Ortiz, J.V., Izmaylov, A.F., Sonnenberg, J.L., Williams, Ding, F., Lipparini, F., Egidi, F., Goings, J., Peng, B., Petrone, A., Henderson, T., Ranasinghe, D., Zakrzewski, V.G., Gao, J., Rega, N., Zheng, G., Liang, W., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Throssell, K., Montgomery Jr., J.A., Peralta, J.E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M.J., Heyd, J.J., Brothers, E.N., Kudin, K.N., Staroverov, V.N., Keith, T.A., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A.P., Burant, J.C., Iyengar, S.S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Millam, J.M., Klene, M., Adamo, C., Cammi, R., Ochterski, J.W., Martin, R.L., Morokuma, K., Farkas, O., Foresman, J.B., Fox, D.J., 2016. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01, Wallingford, CT.

- 32.Li M., Mei Q., Wei B., An Z., Sun J., Xie J., He M. Mechanism and kinetics of ClO-mediated degradation of aromatic compounds in aqueous solution: DFT and QSAR studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;412 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo X., Wei X., Chen J., Xie Q., Yang X., Peijnenburg W.J.G.M. Rate constants of hydroxyl radicals reaction with different dissociation species of fluoroquinolones and sulfonamides: combined experimental and QSAR studies. Water Res. 2019;166 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukui K. The path of chemical reactions - the IRC approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 1981;14:363–368. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marenich A.V., Cramer C.J., Truhlar D.G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Truhlar D.G., Garrett B.C., Klippenstein S.J. Current status of transition-state theory. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:12771–12800. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergsma J.P., Reimers J.R., Wilson K.R., Hynes J.T. Molecular dynamics of the A+BC reaction in rare gas solution. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;85:5625–5643. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ianni, J.C., 2018. Kintecus, Windows Version 6.50, in: URL (Ed.), 〈www.kintecus.com〉.

- 39.Hua Z., Kong X., Hou S., Zou S., Xu X., Huang H., Fang J. DBP alteration from NOM and model compounds after UV/persulfate treatment with post chlorination. Water Res. 2019;158:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo J., Liu T., Zhang D., Yin K., Wang D., Zhang W., Liu C., Yang C., Wei Y., Wang L., Luo S., Crittenden J.C. The individual and Co-exposure degradation of benzophenone derivatives by UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS in different water matrices. Water Res. 2019;159:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ECOSAR V 2.0, U.S.E.P.A., Washington, D.C.

- 42.T.E.S.T. V 5.1.1, U.S.E., 2020. User’s guide for T.E.S.T. (version 5.1.1) (toxicity estimation software tool): a program to estimate toxicity from molecular structure.

- 43.Wu J., Gao Y., Qin Y., Li G., An T. Photochemical degradation of fragrance ingredient benzyl formate in water: mechanism and toxicity assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021;211 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.111950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.An Z., Li M., Huo Y., Jiang J., Zhou Y., Jin Z., Xie J., Zhan J., He M. The pH-dependent contributions of radical species during the removal of aromatic acids and bases in light/chlorine systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;433 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo S., Wei Z., Dionysiou D.D., Spinney R., Hu W.-P., Chai L., Yang Z., Ye T., Xiao R. Mechanistic insight into reactivity of sulfate radical with aromatic contaminants through single-electron transfer pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;327:1056–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadanshio P.P., Wankhede S.B., Chaudhari P.D. A validated stability indicating HPTLC method for estimation of ribavirin in capsule in presence of its alkaline hydrolysis degradation product. Anal. Chem. Lett. 2014;4:343–358. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J., Lin Z., Lan Y., Ren G., Chen D., Huang F., Hong M. A multistep oriented attachment kinetics: coarsening of ZnS nanoparticle in concentrated NaOH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12981–12987. doi: 10.1021/ja062572a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belal F., Sharaf El-Din M.K., Eid M.I., El-Gamal R.M. Validated stability-indicating liquid chromatographic method for the determination of ribavirin in the presence of its degradation products: application to degradation kinetics. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015;53:603–611. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmu092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao J., Luo C., Gan L., Wu D., Tan F., Cheng X., Zhou W., Wang S., Zhang F., Ma J. A comparative study of UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS for the degradation of micro-pollutants: kinetics and effect of water matrix. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27:24531–24541. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08794-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guan Y.-H., Chen J., Chen L.-J., Jiang X.-X., Fu Q. Comparison of UV/H2O2, UV/PMS, and UV/PDS in destruction of different reactivity compounds and formation of bromate and chlorate. Front. Chem. 2020:8. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.581198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guan Y.-H., Ma J., Liu D.-K., Ou Z.-f, Zhang W., Gong X.-L., Fu Q., Crittenden J.C. Insight into chloride effect on the UV/peroxymonosulfate process. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;352:477–489. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lei Y., Lu J., Zhu M., Xie J., Peng S., Zhu C. Radical chemistry of diethyl phthalate oxidation via UV/peroxymonosulfate process: Roles of primary and secondary radicals. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;379 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie P., Ma J., Liu W., Zou J., Yue S., Li X., Wiesner M.R., Fang J. Removal of 2-MIB and geosmin using UV/persulfate: Contributions of hydroxyl and sulfate radicals. Water Res. 2015;69:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sbardella L., Velo-Gala I., Comas J., Rodríguez-Roda Layret I., Fenu A., Gernjak W. The impact of wastewater matrix on the degradation of pharmaceutically active compounds by oxidation processes including ultraviolet radiation and sulfate radicals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;380 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.120869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.