Abstract

The myometrium undergoes progressive tissue remodeling from early to late pregnancy to support fetal growth and transitions to the contractile phase to deliver a baby at term. Much of our effort has been focused on understanding the functional role of myometrial smooth muscle cells, but the role of extracellular matrix is not clear. This study was aimed to demonstrate the expression profile of sub-sets of genes involved in the synthesis, processing, and assembly of collagen and elastic fibers, their structural remodeling during pregnancy, and hormonal regulation. Myometrial tissues were isolated from non-pregnant and pregnant mice to analyze gene expression and protein levels of components of collagen and elastic fibers. Second harmonic generation imaging was used to examine the morphology of collagen and elastic fibers. Gene and protein expressions of collagen and elastin were induced very early in pregnancy. Further, the gene expressions of some of the factors involved in the synthesis, processing, and assembly of collagen and elastic fibers were differentially expressed in the pregnant mouse myometrium. Our imaging analysis demonstrated that the collagen and elastic fibers undergo structural reorganization from early to late pregnancy. Collagen and elastin were differentially induced in response to estrogen and progesterone in the myometrium of ovariectomized mice. Collagen was induced by both estrogen and progesterone. By contrast, estrogen induced elastin, but progesterone suppressed its expression. The current study suggests progressive extracellular matrix remodeling and its potential role in the myometrial tissue mechanical function during pregnancy and parturition.

Keywords: myometrium, extracellular matrix, collagen, elastic fibers, steroid hormones

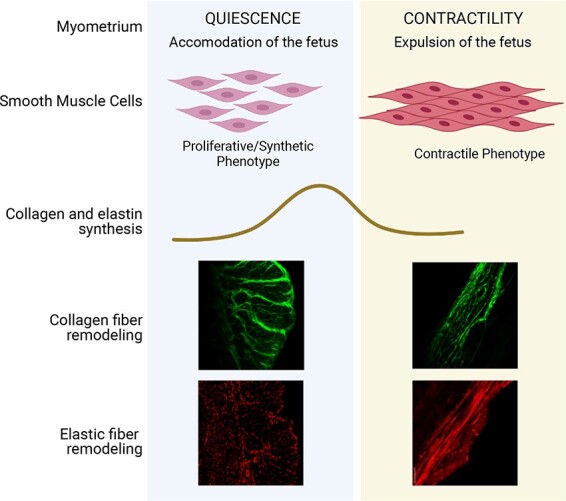

The collagen and elastic fibers undergo structural reorganization from early to late pregnancy and the expression of both collagen and elastin is under the influence of steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex, dynamic, acellular, and fundamental component of all tissues. It provides three-dimensional architectural, mechanical, and biochemical signals to mediate a myriad of cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, migration, and survival [1, 2]. The matrisome—defined as the ensemble of ECM and ECM-associated proteins—comprises the products of several hundred genes in both human and mouse genomes [3]. It constitutes 1–1.5% of the mammalian proteome, comprising almost 300 proteins, including 43 collagen subunits, ~three dozen proteoglycans, and around 200 glycoproteins [1, 3]. The composition of ECM is tissue specific, driven by its physiological function. For example, tendons are rich in fibrillar collagen, blood vessels are rich in elastic fibers, and the brain is rich in glycosaminoglycans [2, 4].

The composition and structure of ECM is usually determined during embryonic development; however, it undergoes constant remodeling to maintain tissue homeostasis in adult life [1]. Alterations to composition and structure via degradation, new deposition, or modification can mediate ECM remodeling. This remodeling is crucial for regulating different developmental processes such as the morphogenesis of the intestine and lungs, as well as of the mammary and submandibular glands [1]. Dysregulation of ECM remodeling results in a wide variety of pathological conditions including fibrosis and cancer [1]. Tissues are subjected to different types of forces, including compressive, tensile, fluid shear stress, and hydrostatic pressure [5]. These forces are endured by tissue biomechanical properties, which are primarily determined by the fibrous proteins of ECM—collagen and elastic fibers [2].

The weight of the human uterus increases 11-fold during pregnancy; no other tissue or organ in the body undergoes such dramatic growth in adult life [6]. During this time, there is a significant remodeling of the ECM accompanied by cellular hyperplasia and hypertrophy [7–9]. The ECM plays a critical role in the maintenance of myometrial tissue architecture, strength, and contractile function, which is evident from knockout mouse models. Myometrium lacking decorin and biglycan exhibits impaired uterine contractions [10]. Conditional deletion of Adamts9, a serine protease known to cleave the ECM protein versican, causes parturition defects due to perturbed myometrial ECM remodeling and smooth muscle differentiation [11]. Further, the gene expression levels of contractile associated proteins were significantly reduced in Adamts9 deficient myometrium, indicating that the ECM organization is essential to mount contractile response during parturition [11].

Smooth muscle cells of the myometrium undergo a phased program of overlapping phenotypic modulation from proliferative to synthetic to fully differentiated contractile phenotype from early to late pregnancy [9]. Much of the ECM is synthesized during the synthetic phase [9]. In the rat uterus, mRNA expression of collagen and elastin increases during the synthetic phase and declines as the myometrium transitions to the contractile phase [12]. In human uterus, collagen I and III mRNA levels are higher in pregnant, non-laboring samples compared to non-pregnant (NP) myometrium [13]. Further, collagen increases seven-fold and elastin increases five- to six-fold in pregnancy [6]. The structural reorganization of collagen fibers from wavy to linearized form is known to facilitate tumor cell migration and metastasis, indicating alterations to tissue mechanical homeostasis and function [14]. In mouse cervix, the thin, more linear collagen fibers transform into thicker, wavy bundles when pregnancy progresses. These morphological changes are highly correlative of declining tissue rigidity upon cervical softening [15, 16]. However, the structural reorganization of collagen and elastic fibers in mouse myometrium during pregnancy is not known.

Unlike ECM in other tissues, the structure, composition, and function of the ECM in reproductive tissues are under strict regulation of steroid hormones—estrogen and progesterone. Collagen, elastin, and other components of ECM are induced by estrogen, progesterone, and mechanical stretching in rat and rabbit uterus [12, 17]. Because of hormonal regulation, the dramatic cyclical remodeling of ECM between pregnant and NP states is carefully orchestrated. We have previously demonstrated that the factors involved in the synthesis, processing, and assembly of collagen and elastic fibers are differentially regulated by estrogen and progesterone in mouse cervix [18]. Further, we have also demonstrated that the structural reorganization was under the influence of these hormones in mouse cervix [18]. Estrogen and progesterone influence collagen synthesis in paraurethral tissues, the vagina, and 3D cultures of human cervical fibroblasts [19, 20]. The role of estrogen or synergic effect of estrogen and progesterone on the induction of collagen and elastin in mouse myometrium; however, is not yet known.

In this study, we have demonstrated that the myometrial collagen and elastic fibers undergo structural reorganization over the course of pregnancy. Further, we have demonstrated that the gene expression of collagen and elastin is differentially induced in response to estrogen and progesterone in mouse myometrium.

Methods

Mice

The CD1 and C57B6/129sv mice used in this study ranged from 2 to 4 months of age. For timed pregnancies, breeding pairs were set up in the morning, and the presence of a vaginal plug was checked for 6 h later. The presence of a vaginal plug was considered day 0 of pregnancy. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals humane animal care standards. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Vermont approved all research protocols.

17β-estradiol and progesterone administration to ovariectomized mice

Ovariectomies were performed on female CD1 mice that were 7–8 weeks of age. After 2 weeks, ovariectomized mice were administered with vehicle (100 μl corn oil) or 17β-estradiol (E, 100 ng, s/c). The tissues were collected 6, 12, 18, or 24 h after E treatment. Progesterone (P) treatment was given to the ovariectomized mice as follows: vehicle, P (1 mg), P (1 mg) + E (10 ng), or E (100 ng) − 2 days of rest − P (1 mg). The tissues were collected after 24 h.

Myometrial tissue collection

Myometrial tissues were collected from NP, various time points at gestation, and 1 day postpartum (PP) mice. Non-pregnant mouse tissue was collected during metestrus, which was assessed by vaginal exfoliative cytology. Myometrial tissues were collected from the uterus after scraping off the endometrial layer. Tissues were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C until processing.

Gene expression analysis using quantitative polymerase chain reaction

RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test B) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to extract total RNA. cDNA was prepared using iScript reverse transcription supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). SYBR Green was used to perform this reaction. Gene expression was calculated according to the 2–ΔΔCt method. The target gene expression was normalized to the expression of Rplp0.

Preparation of PBS and urea extracts from myometrial tissues

Frozen myometrial tissues were pulverized, suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% protease inhibitors and EDTA (Thermo Scientific), and homogenized. The samples were centrifuged at 4°C at 13 000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was collected as the PBS soluble protein fraction. The remaining pellet was suspended in 6 M urea buffer containing 1% protease inhibitors and EDTA (Thermo Scientific), homogenized, and left on a gentle rotation at 4°C for 24 h. The samples were centrifuged at 4°C at 13 000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected as the urea soluble fraction. Both PBS and urea fractions were exchanged with an equivalent volume of 0.5 M Tris/0.5% SDS, pH 8.0 buffer and concentrated using Vivaspin ultrafiltration spin columns (Vivaspin 2, 5 kDa MWCO, Cytiva Life Sciences). Protein concentration was estimated using a BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific).

Western blot

Twenty micrograms of each protein sample were boiled at 95°C for 10 min in Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) with β-mercaptoethanol. The samples were loaded, alongside a protein standard (Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope, Bio-Rad), into a 10% Tris–HCl gel. Gel electrophoresis was run at 50 V, until passing through the stacking gel, where the voltage was then increased to 100 V and run for another hour. Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) at 100 V for 1 h at 4°C. Membranes were blocked at room temperature in 3% blotting-grade blocker non-fat dry milk in TBST (Bio-Rad) for 1 h. The membranes were incubated with primary antibody in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used in this study are Collagen Type I (Millipore, AB765P, 1:500, Host: Mouse), Collagen Type III (Proteintech, 22734-1-AP, 1:1000, Host: Rabbit), Elastin (Elastin Products Company, PR385, 1:500, Host: Rabbit) and β-actin (Cell Signaling, Catalog No.: 3700S, 1:1000). The following day, the membranes were incubated with their respective Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody (Goat anti-mouse IgG (H/L): HRP, Catalog No.: 1706516 or Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H/L): HRP, Catalog No.: 1706515, Bio-Rad, 1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was imaged with Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare).

Confocal microscopy imaging

Frozen tissue sections were fixed in acetone for 10 min and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Life Technologies) for 30 min at room temperature in a moist chamber. Elastin primary antibody (Elastin Products Company, Catalog No.: PR385, concentration used 1:250, Host: Rabbit) diluted in blocking solution was added to each section and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, the sections were washed with PBS and then incubated with Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Catalog No.: A32732, concentration used 1:250) in blocking solution for 30 min at room temperature. Slides were washed and coverslips were mounted to the slides using Prolong Gold containing DAPI (Life Technologies). Images were captured at the anti-mesometrial region of the uterine sections using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope galvanometer scanner with single illumination point scan as fast as 8 frames per second for a 512 × 512-pixel field, and up to 4096 × 4096 pixels image capture.

Second harmonic generation imaging of collagen fibers

Second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging and analysis were performed as described [21]. Briefly, tissue samples were embedded into OCT (Tissue Tek, Indiana) and were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cross-sections of 50 μm were prepared and stored at −80°C until processing. Frozen sections were thawed and covered with 0.1 M PBS to maintain hydration during imaging. The slides were imaged at the anti-mesometrial region of the uterine sections using a Zeiss LSM7 inverted microscope with an Achroplan 40×/0.8 W objective lens. A Chameleon XR pulsed Ti:sapphire laser (Coherent, CA) tuned to 900 nm was focused onto the tissue and the resulting SHG signal was detected at 450 nm. ImageJ was used to analyze all images.

Transmission electron microscopy

Uterine tissues were collected from NP mice in metestrus and pregnant mice at gestation days 12 and 18 after perfusion with 1% glutaraldehyde/4% paraformaldehyde fixative in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. These tissues were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde/0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight. The transverse myometrial strips were dissected and processed as previously described [18]. Briefly, samples were rinsed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, postfixed with osmium tetroxide, and en bloc stained with tannic acid and uranyl acetate. The tissues were then dehydrated using ethanol and embedded in Epon (EMbed-812; Electron Microscopy Sciences). Thin sections (60 nm) were cut and mounted on formvar-coated grids. The grids were then counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. A JEOL 1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA, Inc) operating at 60 or 80 kV was used to capture images and an AMT-XR611 11-megapixel CCD camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques) was used to capture digital images.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism software (GraphPad Software). A one-way analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett multiple comparisons test was used to compare multiple groups. The values were expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM); values were considered significant when P < 0.05. Data were normally distributed with similar variances between the groups. The number of animals used and data analysis are provided in the figure legends.

Results

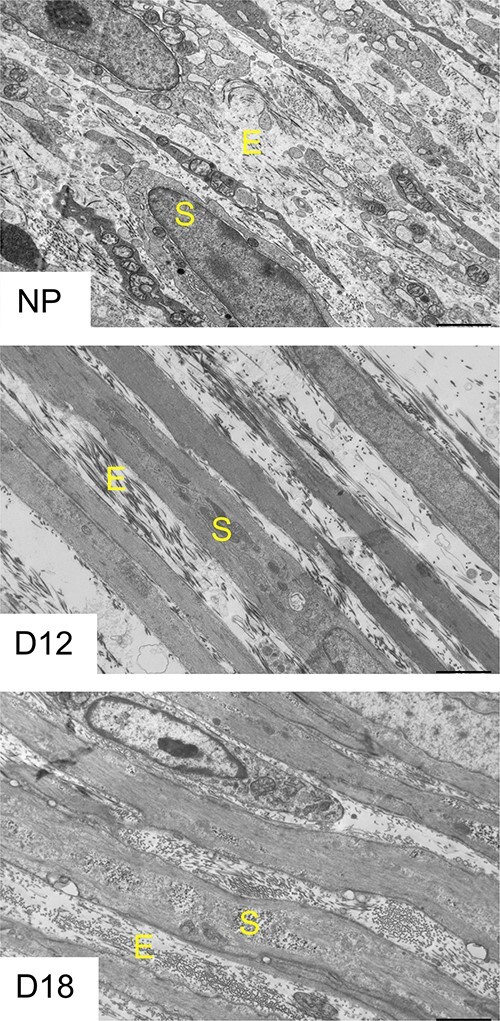

Structural reorganization of ECM in the pregnant mouse myometrium

To visualize ultrastructural changes of ECM in mouse myometrium related to smooth muscle bundles, we performed transmission electron microscopic imaging. In NP myometrium, the ECM and smooth bundles are dispersed. As pregnancy progresses, the ECM and smooth muscle bundles are tightly compacted. The ultrastructure of ECM demonstrates that the ECM is reorganized through pregnancy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural reorganization of ECM in mouse myometrium during pregnancy. Transmission electron microscopy images of NP, gestation day 12 and day 18 mouse myometrium. Images are taken at 2500× of the circular layer of the myometrium (n = 3/time point). E—extracellular matrix showing collagen fibers, S—smooth muscle bundles.

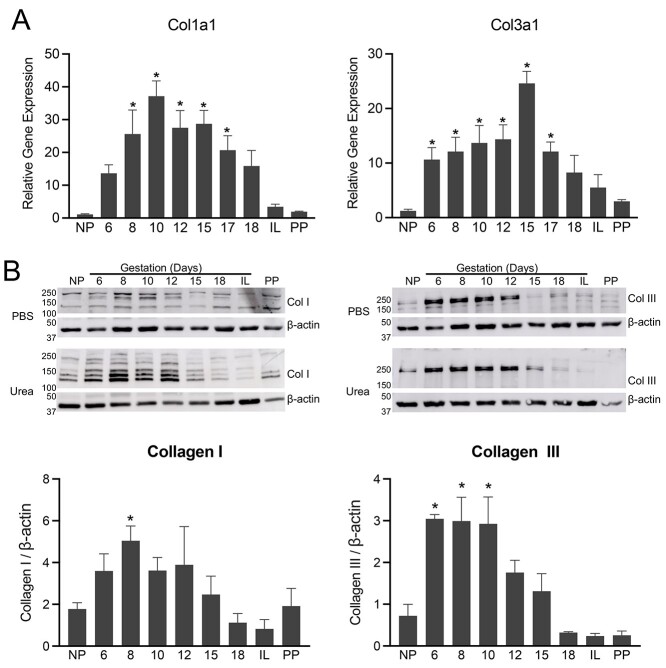

Structural reorganization of fibrillar collagen in the pregnant mouse myometrium

Among all ECM proteins, fibrillar collagens are a major group of proteins, which determine tissue mechanical function [22]. Type I and III collagens belong to a fibril-forming collagen family, which is the most predominant group and plays an important role in providing structural integrity and tissue strength [22, 23]. To identify the expression profile of sub-sets of genes encoding fibrillar collagens in mouse myometrium over the course of pregnancy, we isolated tissues from NP, at various gestational time-points starting from day 6 to day 18, and PP mice. We analyzed the expression of genes encoding subunits of fibrillar collagens, such as collagen type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a1) and collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain (Col3a1). The mRNA expression of Col1a1 and Col3a1 is significantly induced on gestation day 6 or 8 compared to NP myometrium. The mRNA levels are significantly high until gestation day 17 (Figure 2A). To analyze protein levels, we prepared whole tissue lysates with PBS to isolate soluble proteins, followed by urea to release fibrillar collagen integrated into the ECM. Consistent with its mRNA levels, the protein levels of collagens I and III are significantly increased during pregnancy (Figure 2B). These results indicate that collagens are highly induced in mouse myometrium during pregnancy.

Figure 2.

Gene expression and protein levels of fibrillar collagen I and III in mouse myometrium during pregnancy. (A) mRNA expression of genes encoding collagen subunits, Col1a1 and Col3a1, in mouse myometrium. NP, gestation days 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 17, 18, IL (in-labor), and PP (n = 6/group, *P < 0.05). (B) Western blot analysis of collagen I and III protein levels in PBS and urea soluble fractions of NP, gestation days 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 18, IL, and PP mouse myometrial tissues. β-Actin was used as a loading control. These are representative images from three independent replicates. Quantitative densitometry analysis of collagen I and III protein levels was determined and is expressed as a ratio to β-actin (mean ± SEM; n = 3). The ratio calculated from both PBS and urea fractions was combined to express total levels.

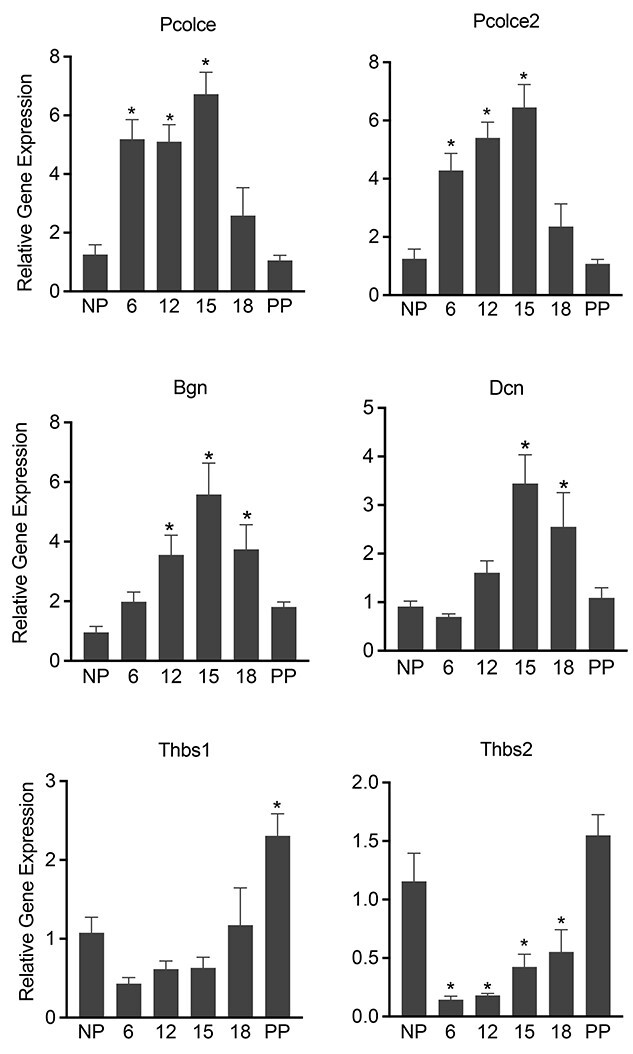

Fibrillar collagens are synthesized as procollagens that contain N and C terminal propeptides, which are cleaved in the extracellular space by N and C-terminal peptidases. The activity of these peptidases is greatly altered by the presence of enhancers. The levels of these factors involved in the processing and assembly of collagen determine the structure and composition of mature collagen present in the ECM. Thus, we analyzed mRNA expression of procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer-1 (Pcolce) and procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer-2 (Pcolce2). Consistent with Col1a1 and Col3a1 gene expression, mRNA expressions of Pcolce and Pcolce2 are significantly induced from day 6 through day 15 (Figure 3). The synthesis, processing, and assembly of fibrillar collagen is also influenced by multiple other groups of ECM proteins, notably, proteoglycans and matricellular proteins [24–26]. We have analyzed the gene expression of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans, such as biglycan and decorin, which are known regulators of fibrillar collagen synthesis and assembly [27, 28]. The mRNA levels of both biglycan and decorin are significantly upregulated in the pregnant myometrium (Figure 3). We also analyzed mRNA expression of matricellular proteins, thrombospondin 1 and 2 (Thbs1 and 2) [26, 29]. The mRNA level of Thbs1 is not significantly altered during pregnancy. By contrast, the mRNA level of Thbs2 is significantly downregulated on day 6 through day 18 of pregnancy (Figure 3). Collectively, these results show that the genes encoding factors that influence collagen synthesis, processing, and assembly are differentially regulated in mouse myometrium during pregnancy.

Figure 3.

Gene expression of factors involved in the synthesis, processing, and assembly of fibrillar collagen in the pregnant mouse myometrium. mRNA expression of Pcolce, Pcolce2, Bgn, Dcn, Thbs1 and 2 in mouse myometrium. NP, gestation days 6, 12, 15, 18, and PP (n = 6/group, *P < 0.05).

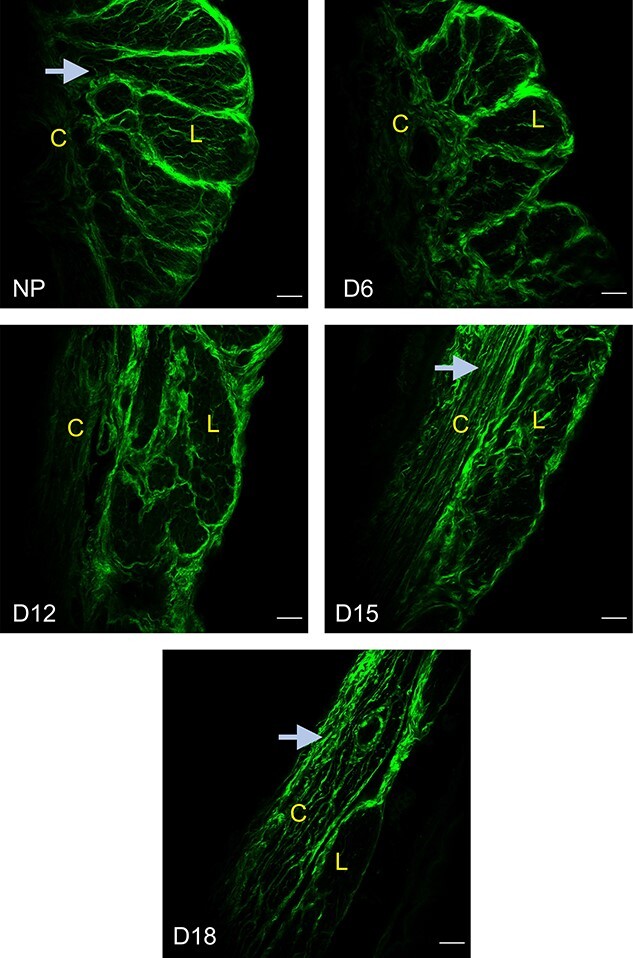

The SHG imaging of fibrillar collagen is widely used in tissues to spatially resolve collagen structure that is related to tissue mechanical properties [15, 18, 30]. Therefore, we examined the structural reorganization of collagen fibers in myometrium over the course of pregnancy through SHG imaging as we described previously [18, 21]. We visually examined the images to assess linearity and waviness of collagen fibers. The collagen fibers are wavy in the NP myometrium but appear linear by gestation day 18 (Figure 4). These results revealed that collagen fibers undergo structural reorganization from early to late pregnancy.

Figure 4.

Structural reorganization of fibrillar collagen in the pregnant mouse myometrium. SHG imaging of fibrillar collagen in NP, gestation days 6, 12, 15, and 18 myometrium. The arrows indicate the change in the morphology of collagen fibers from wavy to linear as pregnancy progresses. Representative images from three independent replicates. Imaging settings vary between images for optimal visualization of morphology. (L—longitudinal layer; C—circular layer). Scale bar: 50 μm.

Structural reorganization of elastic fibers in the pregnant mouse myometrium

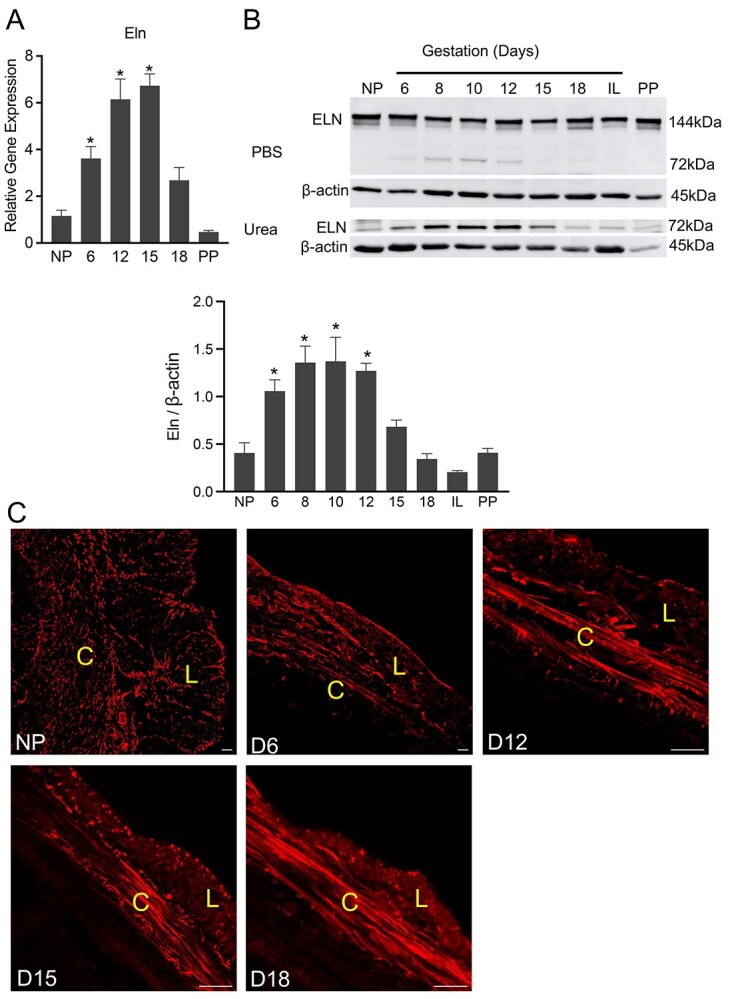

We analyzed mRNA levels of elastin (Eln) in mouse myometrium. The mRNA expression of Eln is significantly induced from day 6 through day 18 (Figure 5A). Elastin is synthesized as a monomer (72 kDa), which then joins to form dimers (144 kDa) to integrate onto the microfibril scaffolds. It is evident from PBS soluble fraction that the soluble elastin, mostly in the form of dimer, was abundant in the mouse myometrium (Figure 5B). We then extracted the remaining tissue with urea to release the elastin integrated into the ECM. Consistent with its gene expression, elastin levels increased from early to late pregnancy indicating its potential role in providing elasticity to the pregnant myometrium (Figure 5B). The morphological assessment of elastic fibers through the localization of elastin demonstrates that elastic fibers undergo structural reorganization over the course of pregnancy. In NP myometrium, the elastic fibers are thinner and scattered and they become thick, linear bundles as pregnancy progresses (Figure 5C). These results indicate that elastic fibers are progressively remodeled from early to late pregnancy, potentially to assist contractility by providing tissue resilience for myometrium at parturition.

Figure 5.

Elastic fibers in the pregnant mouse myometrium—gene expression and protein levels of elastin and structural reorganization of elastic fibers. (A) mRNA expression of Eln in mouse myometrium. NP, gestation days 6, 12, 15, 18, and PP (n = 6/group, *P < 0.05). (B) Western blot analysis of elastin levels in PBS and urea soluble fractions of NP, gestation days 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 18, in-labor (IL) and PP mouse myometrial tissues. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Representative images from three independent replicates. The MW of tropoelastin monomer is 72 kDa and of dimer is 144 kDa. Quantitative densitometry analysis of tropoelastin monomer levels was determined and is expressed as a ratio to β-actin (mean ± SEM; n = 3). The ratio calculated from both PBS and urea fractions was combined to express total levels. (C) Confocal imaging of tropoelastin of NP, gestation days 6, 12, 15, and 18 myometrium. Representative images from three independent replicates. Scale bar: 20 μm.

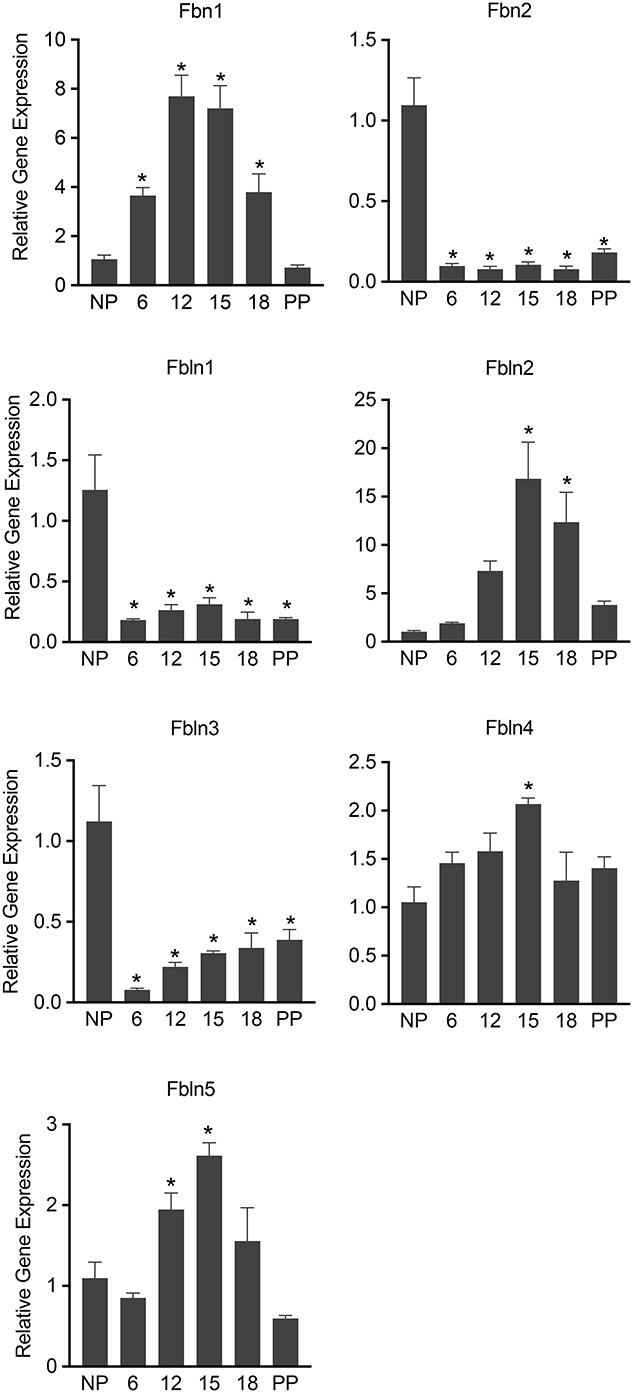

The synthesis, processing, and assembly of elastic fibers is a complex process that requires multiple factors, similar to that of collagen fibers [4]. To evaluate gene transcription involved in the synthesis and assembly of elastic fibers, we analyzed mRNA levels of fibrillin (Fbn1 and 2) and of fibulins (Fbln1-5). Fibrillin1 and 2 are constituents of a microfibril scaffold upon which elastin will be integrated. The mRNA expression of Fbn1 is significantly induced from day 6 through day 18 (Figure 6). By contrast, the mRNA level of Fbn2 is drastically reduced from early pregnancy (Figure 6). Fibulins are a group of ECM proteins critical for elastic fiber assembly [31]. In the absence of these proteins, the elastic fiber organization is severely disrupted leading to compromised tissue function. For example, mice lacking fibulin-5 experience pelvic organ prolapse due to the inability of elastin to assemble into mature fibers [32]. Among these five fibulins, fibulin 2, 4, and 5 are significantly induced, but fibulin 1 and 3 are significantly downregulated in the mouse myometrium during pregnancy (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Gene expression of factors involved in the synthesis, processing, and assembly of elastic fibers in the pregnant mouse myometrium. mRNA expression of Fbn1, 2, and Fbln1-5 in mouse myometrium. NP, gestation days 6, 12, 15, 18, and PP (n = 6/group, *P < 0.05).

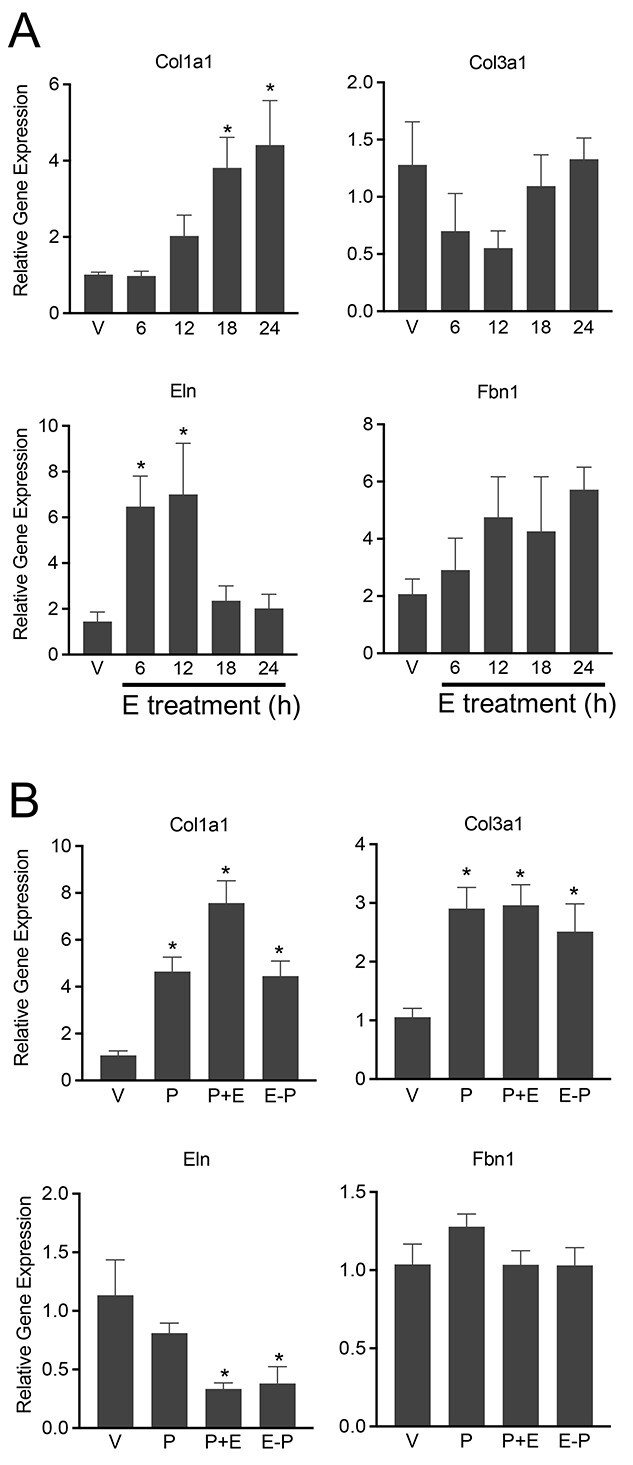

Steroid hormones differentially induce myometrial collagen and elastin gene expression

Differential regulation of ECM gene expression by steroid hormones could play a key role in mediating dynamic alterations to the structure and composition of ECM [18]. To identify the distinct as well as the synergistic role of estrogen and progesterone on collagen and elastin gene expression, we utilized ovariectomized mice exogenously administered with estrogen, progesterone, or both. In response to estrogen, Col1a1 mRNA was significantly induced at 18 h, but there was no change in the expression of Col3a1 (Figure 7A). In contrast to Col1a1, the Eln was induced very early, at 6 h post-estrogen treatment (Figure 7A). To examine the effect of either progesterone alone or the combined effect of both estrogen and progesterone, ovariectomized mice were treated with either progesterone alone or a combination of estrogen and progesterone. We have used two different combinations of treatments. The administration of both estrogen and progesterone together mimics synergistic actions. In another group, we have administered estrogen, to induce progesterone receptors, followed by 2 days of rest and then progesterone administration. In this experiment, both Col1a1 and Col3a1 were significantly induced by progesterone (Figure 7B). Further, the combination of both estrogen and progesterone induced the highest expression of Col1a1 compared to all other groups (Figure 7B). In response to progesterone, the Eln expression was not altered, but its expression was significantly reduced in response to the combination of both estrogen and progesterone (Figure 7B). The Fbn1 gene expression was not significantly altered in response to estrogen, progesterone, or both (Figure 7). These results indicate that estrogen and progesterone significantly induce Col1a1 gene expression. By contrast, estrogen induces Eln but progesterone inhibits its gene expression.

Figure 7.

Steroid hormones differentially induce myometrial collagen and elastin gene expression. (A) Induction of collagen and elastin gene expression in response to 17β-estradiol in ovariectomized mouse myometrium. mRNA expression of Col1a1, Col3a1, Eln, and Fbn1 in response to 17β-estradiol (E) in ovariectomized mouse myometrium. Ovariectomized mice were treated with vehicle (V) or 17β-estradiol (100 ng/mouse, s/c) for 6, 12, 18, or 24 h (n = 6/group, *P < 0.05). (B) Induction of collagen and elastin gene expression in response to progesterone and 17β-estradiol in ovariectomized mouse myometrium. mRNA expression of Col1a1, Col3a1, Eln, and Fbn1 in response to progesterone (P) or progesterone and 17β-estradiol (E) in ovariectomized mouse myometrium. Ovariectomized mice were treated with P (1 mg/mouse, s/c), P (1 mg) + E (10 ng), E (100 ng) − 2 days of rest – P (1 mg). The tissues were collected after 24 h (n = 6/group, *P < 0.05).

Discussion

The ECM is the predominant contributor of tissue strength in almost all tissues in the body [33]. It is presumably supporting the myometrium to endure progressive mechanical loading during pregnancy for fetal growth and subsequently to exert forceful rhythmic contractions at term for the successful delivery of the fetus [34]. The tissue’s mechanical properties are predominantly contributed by the collagen and elastic fibers [33]. In the current study, we have illustrated the structural reorganization of collagen and elastic fibers in mouse myometrium over the course of pregnancy. The assessment of collagen fiber morphology is widely reported as a reliable indicator of ECM remodeling and tissue mechanical function during physiological as well as pathological conditions [1]. Our data demonstrate that the collagen and elastic fibers undergo orchestrated remodeling from early to late pregnancy.

The fibrillar collagens are highly expressed in both endometrium and myometrium of the pregnant mouse uterus [35–37]. Several studies have reported remodeling of the fibrillar collagen in the pre/peri-implantation and decidualized endometrium [35, 38]. In rat myometrium, the gene expression of sub-set of collagens and elastin is highly induced during pregnancy [12]. In our study, the gene expression of sub-units of fibrillar collagen I and III is induced as early as day 6 of gestation in mouse myometrium. Consistent with their mRNA expression, the extractable protein levels are also increased very early in pregnancy. The transcripts encoding some of the factors involved in the synthesis, processing, and assembly are differentially expressed in the pregnant myometrium. Proteoglycans are another major group of ECM proteins known to regulate collagen processing and assembly. Mice lacking these proteoglycans exhibit compromised tissue strength due to disrupted collagen ultrastructure, with the deletion of both decorin and biglycan in mice leading to parturition defects. Though the collagen ultrastructure of myometrium is not reported in these mice, the cervix has been shown to exhibit severe collagen fibril abnormalities and reduced tissue strength [18]. In contrast to most of the factors involved in collagen synthesis and assembly, gene expression of the matricellular proteins such as thrombospondin 1 and 2 is significantly reduced in the pregnant myometrium. Collectively, these data demonstrate collagen synthesis in the pregnant mouse myometrium. Further, the increased levels of collagens at very early pregnancy indicate that the myometrial tissue remodeling is initiated very early to accommodate a growing fetus. In addition, it is supported by the differential expression of some of the factors involved in the collagen synthesis, processing, and assembly. These changes might likely contribute to the alterations in the structural reorganization of fibrillar collagen through pregnancy.

The structural reorganization of collagen fibers is a hallmark of many biological processes such as developmental morphogenesis, fibrosis, wound healing, tumor growth, and metastasis [1, 14]. The SHG imaging is widely used to examine the fibrillar collagen architecture to discern underlying aspects of collagen fiber remodeling [15, 30]. The SHG imaging of mammary gland tumor revealed that collagen fibril linearity increases with the progression of tumor from benign to malignancy correlating with elevated tissue stiffness [14]. In the pregnant mouse cervix, the dramatic changes in the morphology of fibrillar collagen from early to late pregnancy are reported based on the visualization of SHG. The collagen fibers are thinner and linear in the early pregnancy and are reorganized into thick and wavy bundles at term [15]. On the other hand, in the pregnant myometrium, the collagen fiber reorganization occurs in reverse order. In the pregnant myometrium, the collagen fibers appear wavy in the early pregnancy and turn into straight, linear bundles at term. The striking difference in the structural reorganization of myometrial and cervical collagen fibers is highly correlative of their opposing roles in pregnancy and parturition. The myometrium supports pregnancy by accommodating the growth of the fetus by potentially increasing its stiffness, but in contrast, the rigid cervix progressively softens to dilate sufficiently to allow the delivery of the fetus.

Elastic fibers are critical components of ECM providing tissue elasticity and resilience [39]. In contrast to collagen fibers that are highly concentrated in the load-bearing tissues such as tendon, the elastic fibers are highly concentrated in the tissues such as blood vessels, which require stretch and recoil [39]. Along with collagen fibers, the elastic fibers are also known to contribute to tissue strength [18]. The elastic fibers are considered permanent once laid, except in the tissues of the reproductive system [6, 40, 41]. These fibers are reported to play an important role in the maintenance of mechanical homeostasis of the vaginal wall [32, 40]. Disruption of elastic fiber assembly results in compromised tissue strength and pelvic floor disorders in mice [32, 40]. Our data demonstrate that the elastic fibers undergo structural remodeling through pregnancy similar to collagen fibers. The gene expression and protein levels are increased in the pregnant myometrium. The factors associated with the assembly of elastic fibers are differentially expressed in the pregnant myometrium, supporting the remodeling of the elastic fibers. The changes in the gene expression of factors influencing synthesis, processing, and assembly are presumably being used as a key to modulate structural reorganization of the elastic fibers and thus tissue mechanical function. The function of elastic fibers in the myometrial tissue could likely be to preserve tissue integrity at the time of labor when executing forceful contractions through their stretch and recoil properties. It is presumably assisting the circular layer of the mouse myometrium to facilitate peristaltic movement in the uterine horn to move the fetuses from ovarian to vaginal end.

There is a discrepancy among gene expression, extractable protein levels, and morphological changes of collagen and elastin in the pregnant myometrium. The reason for decline in the gene expression of collagen and elastin at late pregnancy (before term) is unclear at present. We speculate that the morphological changes to collagen and elastic fibers might be dictated by fetal growth and accumulation of fetal fluids. To endure this mechanical loading exerted by the growing fetus, smooth muscle cells undergo hyperplasia and followed by hypertrophy along with the elevated synthesis of collagen and elastin. The synthesis, processing, and assembly of collagen and elastin are complex processes. Further, the collagen and elastin undergo extensive post-translational modifications and thus their protein levels might be maintained till term due to time-lapse in the protein synthesis. However, in our studies, the protein levels are low in late pregnancy. We would like to caution that these levels represent urea extractable proteins, but not absolute quantities of proteins present in the myometrium. The reason could be due to reduced extractability contributed by several possible mechanisms including but not limited to elevated collagen and elastin cross-linking. Therefore, the morphological changes are ongoing until term even though the gene expression changes occur much earlier and decreased drastically before term. However, the experimental evidence is warranted to support this hypothesis.

In contrast to many other collagen and elastin-rich connective tissues, the expression of collagen and elastin is regulated by steroid hormones, estrogen and progesterone, in the reproductive tissues [12, 18, 20]. The ovarian cyclicity and pregnancy status has a profound effect on reproductive tissue growth and morphology. To meet this physiological demand, time-dependent coordinated ECM remodeling is necessary. This could be effectively mediated when the collagen and elastin fibers are under the regulation of steroid hormones. Our data demonstrate that both collagen and elastin are significantly induced in the pregnant myometrium. Further, in response to the estrogen gene, the expression of both collagen and elastin is induced in the ovariectomized mouse model. Importantly, the elastin was induced as early as 6 h post-estrogen treatment, unlike the collagen, which was induced at 18 h, indicating a temporal difference in the induction of these genes by estrogen. On the contrary, progesterone or a combination of both estrogen and progesterone induce collagen but suppress elastin expression. Consistent with their expression profile in the pregnant myometrium, both collagen and elastic fibers undergo structural remodeling during pregnancy. Collectively, our data suggest that the synthesis, processing, and assembly of collagen and elastic fibers are mediated by concerted actions of estrogen and progesterone. These hormone-regulated progressive changes in the collagen and elastic fibers are likely to have an impact on myometrial tissue mechanical function during pregnancy and parturition.

These findings will have the potential to improve our understanding on the pathogenesis of connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome. These syndromes are caused by mutations in the genes involved in the synthesis, processing, and assembly of collagen and elastic fibers [42, 43]. Women with these connective tissue disorders will have an increased risk of pregnancy and other associated complications including but not limited to preterm birth and uterine rupture [44–46]. Much of our attention has been paid toward the understanding of myometrial smooth muscle cell function. Nevertheless, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that initiate the parturition process is still not clear. Thus, expanding our investigation to include multiple other tissue components might be the best strategy. Emerging evidence suggests that the ECM plays a critical role in cellular and tissue functions. Therefore, along with smooth muscle cells, understanding the functional role of ECM and its components in myometrial tissue function during pregnancy and parturition is warranted.

Authors’ contributions

S.N. designed the study. A.O. and S.N. conducted experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. M.M. supported S.N. to initiate this study and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

All original data are available upon request to the corresponding author. There are no large databases associated with this work.

Acknowledgments

Imaging work was performed at the Microscopy Imaging Center at the University of Vermont. Parts of graphical abstract were created with Biorender.com.

Contributor Information

Alexis Ouellette, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Larner College of Medicine University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA.

Mala Mahendroo, Department of Ob/Gyn and Cecil H. and Ida Green Center for Reproductive Biological Sciences, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Shanmugasundaram Nallasamy, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Larner College of Medicine University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1. Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:786–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mouw JK, Ou G, Weaver VM. Extracellular matrix assembly: a multiscale deconstruction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:771–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hynes RO, Naba A. Overview of the matrisome—an inventory of extracellular matrix constituents and functions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012; 4:a004903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wagenseil JE, Mecham RP. New insights into elastic fiber assembly. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2007; 81:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DuFort CC, Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011; 12:308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woessner JF, Brewer TH. Formation and breakdown of collagen and elastin in the human uterus pregnancy and post-partum involution. Biochem J 1963; 89:75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leppert PC. Tissue remodeling in the female reproductive tract—a complex process becomes more complex: the role of Hox genes. Biol Reprod 2012; 86:98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jorge S, Chang S, Barzilai JJ, Leppert P, Segars JH. Mechanical signaling in reproductive tissues: mechanisms and importance. Reprod Sci 2014; 21:1093–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shynlova O, Tsui P, Jaffer S, Lye SJ. Integration of endocrine and mechanical signals in the regulation of myometrial functions during pregnancy and labour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009; 144:S2–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu Z, Aron AW, Macksoud EE, Iozzo RV, Hai C-M, Lechner BE. Uterine dysfunction in biglycan and decorin deficient mice leads to dystocia during parturition. PLoS One 2012; 7:e29627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mead TJ, Du Y, Nelson CM, Gueye NA, Drazba J, Dancevic CM, Vankemmelbeke M, Buttle DJ, Apte SS. ADAMTS9-regulated pericellular matrix dynamics governs focal adhesion-dependent smooth muscle differentiation. Cell Rep 2018; 23:485–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shynlova O, Mitchell JA, Tsampalieros A, Langille BL, Lye SJ. Progesterone and gravidity differentially regulate expression of extracellular matrix components in the pregnant rat myometrium. Biol Reprod 2004; 70:986–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stewart EA, Floor AE, Jain P, Nowak RA. Increased expression of messenger RNA for collagen type I, collagen type III, and fibronectin in myometrium of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1995; 86:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DLet al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 2009; 139:891–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akins ML, Luby-Phelps K, Mahendroo M. Second harmonic generation imaging as a potential tool for staging pregnancy and predicting preterm birth. J Biomed Opt 2010; 15:026020–026020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yoshida K, Jiang H, Kim M, Vink J, Cremers S, Paik D, Wapner R, Mahendroo M, Myers K. Quantitative evaluation of collagen crosslinks and corresponding tensile mechanical properties in mouse cervical tissue during normal pregnancy. PLoS One 2014; 9:e112391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Csapo A, Erdos T, Mattos CR, Gramss E, Moscowitz C. Stretch-induced uterine growth, protein synthesis and function. Nature 1965; 207:1378–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nallasamy S, Yoshida K, Akins M, Myers K, Iozzo R, Mahendroo M. Steroid hormones are key modulators of tissue mechanical function via regulation of collagen and elastic fibers. Endocrinology 2017; 158:950–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. House M, Tadesse-Telila S, Norwitz ER, Socrate S, Kaplan DL. Inhibitory effect of progesterone on cervical tissue formation in a three-dimensional culture system with human cervical fibroblasts. Biol Reprod 2014; 90:18–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Montoya TI, Maldonado PA, Acevedo JF, Word RA. Effect of vaginal or systemic estrogen on dynamics of collagen assembly in the rat vaginal wall. Biol Reprod 2015; 92:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nallasamy S, Akins M, Tetreault B, Luby-Phelps K, Mahendroo M. Distinct reorganization of collagen architecture in lipopolysaccharide-mediated premature cervical remodeling. Biol Reprod 2018; 98:63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bielajew BJ, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Collagen: quantification, biomechanics and role of minor subtypes in cartilage. Nat Rev Mater 2020; 5:730–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sorushanova A, Delgado LM, Wu Z, Shologu N, Kshirsagar A, Raghunath R, Mullen AM, Bayon Y, Pandit A, Raghunath M, Zeugolis DI. The collagen suprafamily: from biosynthesis to advanced biomaterial development. Adv Mater 2019; 31:e1801651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Biological functions of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: from genetics to signal transduction. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:21305–21309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adams JC, Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 3:a009712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bornstein P, Sage EH. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of cell function. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2002; 14:608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neill T, Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Decorin: a guardian from the matrix. Am J Pathol 2012; 181:380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu T, Bianco P, Fisher LW, Longenecker G, Smith E, Goldstein S, Bonadio J, Boskey A, Heegaard AM, Sommer B, Satomura K, Dominguez Pet al. Targeted disruption of the biglycan gene leads to an osteoporosis-like phenotype in mice. Nat Genet 1998; 20:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bornstein P. Thrombospondins: structure and regulation of expression. FASEB J 1992; 6:3290–3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Campagnola PJ, Loew LM. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nat Biotechnol 2003; 21:1356–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Timpl R, Sasaki T, Kostka G, Chu M-L. Fibulins: a versatile family of extracellular matrix proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003; 4:479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drewes PG, Yanagisawa H, Starcher B, Hornstra I, Csiszar K, Marinis SI, Keller P, Word RA. Pelvic organ prolapse in fibulin-5 knockout mice: pregnancy-induced changes in elastic fiber homeostasis in mouse vagina. Am J Pathol 2007; 170:578–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:802–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Myers KM, Elad D. Biomechanics of the human uterus. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 2017; 9:1–20. 10.1002/wsbm.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Favaro R, Abrahamsohn PA, Zorn MT. 11—Decidualization and endometrial extracellular matrix remodeling. In: Croy BA, Yamada AT, DeMayo FJ, Adamson SL (eds.), The Guide to Investigation of Mouse Pregnancy. Boston: Academic Press; 2014: 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spiess K, Teodoro WR, Zorn TMT. Distribution of collagen types I, III, and V in pregnant mouse endometrium. Connect Tissue Res 2007; 48:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Favaro RR, Raspantini PR, Salgado RM, Fortes ZB, Zorn TM. Long-term type 1 diabetes alters the deposition of collagens and proteoglycans in the early pregnant myometrium of mice. Histol Histopathol 2015; 30:435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diao H, Aplin JD, Xiao S, Chun J, Li Z, Chen S, Ye X. Altered spatiotemporal expression of collagen types I, III, IV, and VI in Lpar3-deficient peri-implantation mouse uterus. Biol Reprod 2011; 84:255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ozsvar J, Yang C, Cain SA, Baldock C, Tarakanova A, Weiss AS. Tropoelastin and elastin assembly. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021; 9:643110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu X, Zhao Y, Gao J, Pawlyk B, Starcher B, Spencer JA, Yanagisawa H, Zuo J, Li T. Elastic fiber homeostasis requires lysyl oxidase-like 1 protein. Nat Genet 2004; 36:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Metaxa-Mariatou V, McGavigan CJ, Robertson K, Stewart C, Cameron IT, Campbell S. Elastin distribution in the myometrial and vascular smooth muscle of the human uterus. Mol Hum Reprod 2002; 8:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malfait F, Castori M, Francomano CA, Giunta C, Kosho T, Byers PH. The Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020; 6:64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Milewicz DM, Braverman AC, De Backer J, Morris SA, Boileau C, Maumenee IH, Jondeau G, Evangelista A, Pyeritz RE. Marfan syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021; 7:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Curry RA, Gelson E, Swan L, Dob D, Babu-Narayan SV, Gatzoulis MA, Steer PJ, Johnson MR. Marfan syndrome and pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. BJOG 2014; 121:610–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cauldwell M, Steer PJ, Curtis SL, Mohan A, Dockree S, Mackillop L, Parry HM, Oliver J, Sterrenberg M, Wallace S, Malin G, Partridge Get al. Maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by Marfan syndrome. Heart 2019; 105:1725–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rudd N, Holbrook K, Nimrod C, Byers P. Pregnancy complications in type IV Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome. The Lancet 1983; 321:50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All original data are available upon request to the corresponding author. There are no large databases associated with this work.