Abstract

Pelvic venous disorders (PeVDs) have replaced the concept of pelvic congestion syndrome encompassing venous origin chronic pelvic pain (VO-CPP) in women. The evaluation of women with VO-CPP includes the assessment for other causes of pelvic pain as well as imaging evaluation for pelvic varicosities measuring greater than 5 mm diameter, ovarian vein diameter, and flow direction, as well as iliac vein diameter and signs of compression. Proper identification of these patients can lead to high degrees of success eliminating chronic pelvic pain following ovarian vein embolization and/or iliac vein stenting. Strong encouragement is provided to use the symptoms, varices, pathophysiology classification for these patients and upcoming research studies on the specific symptoms of patients with VO-CPP will help elucidate patient selection for intervention. Additional future randomized controlled trials are also upcoming to evaluate for outcomes of ovarian vein embolization and iliac vein.

Keywords: chronic pelvic pain, pelvic venous disorders, pelvic congestion syndrome, ovarian vein embolization

Pelvic venous disorders (PeVDs) encompass a spectrum of signs and symptoms that result from abnormal pelvic venous physiology. This includes both the pelvic tributaries/plexuses, namely the ovarian veins (OV), internal iliac veins (IIV), pelvic venous plexuses, as well as the left renal vein (LRV), common iliac veins (CIVs), or pelvic escape points as their corresponding drainage pathways. These conditions include the previously named May-Thurner syndrome, Nutcracker syndrome, and pelvic congestion syndrome, which are no longer the appropriate terminology. 1

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists defines chronic pelvic pain (CPP) as pain symptoms perceived to originate from pelvic organs/structures typically lasting more than 6 months. It is often associated with negative cognitive, behavioral, sexual, and emotional consequences as well as with symptoms suggestive of lower urinary tract, sexual, bowel, pelvic floor, myofascial, or gynecological dysfunction. 2 PeVD may act as the primary or contributing cause of CPP in some patients.

The annual prevalence of CPP was found to be as high as 27%, 3 including 15% in the United States, 4 and is comparable to conditions such as asthma and back pain in the United Kingdom. 5 These rates were higher among the women seeking family medicine or gynecological care. 6 Overlap with other conditions is common, as up to 50% of women with CPP also reported either genitourinary symptoms, irritable bowel syndrome, or both. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia was also higher among women with CPP. 7 CPP is also often associated with a history of sexual and physical abuse as well as psychological conditions such as depression or anxiety. 8

There is significant morbidity and healthcare expenditure associated with CPP, as it is the primary indication for approximately 50% of gynecologic visits, 40% of diagnostic laparoscopies, as well as 10% of hysterectomies, and accounts for more than 2 billion dollars in annual health care costs. 4 9 In up to 40% of women with CPP who undergo laparoscopy, however, an etiology for their pain is not found. 10

Data regarding the proportion of CPP that is of primarily venous origin (VO) is limited; however, small case series suggest this most commonly occurs in multiparous, reproductive age women. 11 12 13 14 A separate, slightly older population with iliac vein obstruction has reported pelvic pain in conjunction with lower extremity symptoms. 15 16 The remainder of this article aims to delineate the anatomy, pathophysiology, and treatment strategies for the management of VO-CPP or PeVD.

Anatomy

The venous drainage of the female pelvis is primarily through the IIV and OVs, which subsequently drain into the CIVs and LRV, respectively. PeVD can be the consequence of reflux (IIV, OV) and/or obstruction (CIV, LRV) and results in increased pressure within the associated venous reservoirs. High pressure within these venous reservoirs can lead to the development of varices and/or symptoms of pain. The four main venous reservoirs are the left renal hilum, the pelvis, the superficial extrapelvic veins (vulva, perineum, inner/posterior thigh), and the superficial/deep veins of the lower extremity. 17 The pelvic escape points are peripheral tributaries of the IIVs and include the internal pudendal veins, obturator veins, round ligament (inguinal) veins, and inferior gluteal veins. These routes can lead to transmission of increased venous pressure in the pelvis to the superficial veins of the vulva and lower extremities, which may cause lower extremity symptoms with or without pelvic pain. 18 19

Pelvic varices can vary in size with the best consensus definition as dilated veins measuring 5 mm or greater in diameter in the periovarian or periuterine space, 20 which can involve the ovarian/pampiniform as well as the uterovaginal plexuses that communicate through the broad ligament. 11 18 21 22 23 Since iliac vein compression or nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions are also considered to be a potential cause for VO-CPP, a venous diameter reduction of 61% or greater is considered significant by intravascular ultrasound (US; VIDIO trial). 24 Given that a greater than 50% iliac vein stenosis may be present in 25 to 33% of the population, it is important to take caution prior to treating a nonthrombotic iliac vein lesion unless there is proper clinical context. 17 25 26 Fig. 1 shows examples of pelvic varices and dilated OVs identified by transabdominal US.

Fig. 1.

Transabdominal ultrasound images demonstrate ( a ) dilated left periovarian veins measuring greater than 5 mm diameter (arrow) and ( b ) a dilated left ovarian vein (arrow).

Pathophysiology

The etiology of CPP is complex, and may have contributions from the interplay between gynecologic, urologic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and physiologic comorbidities. 27 The pathophysiology is multifactorial; however, it likely includes hormonal regulation as there has been some medical success treating PeVD with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs or medroxyprogesterone acetate. 28 Even when a structural cause is found, its effects can persist after definitive treatment due to dynamic and hormonal neuromodulation and become independent of the cause itself. 29 As-Sanie et al postulated that anterior insula glutamatergic neurotransmission and connectivity in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) may play a role in the pathophysiology of CPP and supports central pain amplification as a mechanism of CPP. 30 Increased gray matter density in pain-related areas of the brain may also play a role in CPP and other chronic pain conditions. 31 Pelvic organ cross-sensitization is also a factor contributing to CPP of unknown origin. 32 Cross-sensitization develops as a result of irritation of a pelvic structure and is mediated via both neural (sensory) and hormonal mechanisms. Increase afferent impulses from the irritated pelvic organ sensitize viscerovisceral convergent neurons within the spinal cord and enhance the effects of afferent inputs from adjacent organs. This process can result in visceral hyperalgesia and neurogenic inflammation, which may involve the original organ or even the surrounding structures. 33 Even while adjusting for age and education, pressure-pain thresholds are lower in women with CPP relative to healthy women, suggesting that central pain amplification may play a significant role. 34

Clinical Presentation

The clinical evaluation of a patient presenting with CPP of course requires a detailed history and physical examination, preferably performed by a gynecologist with expertise in CPP. The International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS) developed a template to aid providers in this evaluation; however, signs and symptoms that may represent PeVD were largely omitted. 35 If PeVD is suspected, then referral to a vascular specialist experienced in PeVD is essential.

It is often difficult to separate VO-CPP from non-venous origin, and there is commonly overlap even with individual patients. 7 The signs and symptoms of venous-origin pelvic pain have also been found to be sensitive, but not specific. 36 In the literature, venous origin pelvic pain is reported as typically dull unilateral or bilateral pain with intermittent sharp flares. Adnexal tenderness on bimanual exam may reproduce the pain. Activities that result in a prolonged dependent position of the pelvis, such as standing or walking, as well as exertion, can worsen symptoms. Supine position has been reported to improve the pain, and as such the pain is generally not present in the morning. 13 Prolonged postcoital pelvic ache has been shown to be an indicator of venous origin pelvic pain, typically lasting hours but occasionally for 1 to 2 days. 11 13 36 This symptom, combined with tenderness at the ovarian point, is 94% sensitive and 77% specific for distinguishing a venous origin of CPP. 13 Gibson et al reported that the most common symptoms in females with pelvic source varices were aching, throbbing, and heaviness, as well as worsening during menses in the premenopausal population. 37 Pelvic origin extrapelvic symptoms refer to symptoms that arise from pelvic venous escape points or iliocaval obstruction, and often include pain, discomfort, tenderness, itching, bleeding, or thrombosis. 18 Varicosities are typically localized to the vulva or posteromedial thigh in the distribution of the perineal and inferior gluteal escape points. 17 These patients typically have a history of vulvar or perineal varices during pregnancy, which are more frequent and severe with increased parity. 37

Imaging

Both invasive and noninvasive imaging modalities are able to diagnose pelvic varicose veins, including catheter venography, CT, transabdominal/transvaginal US, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). While catheter venography is the traditional gold standard, noninvasive imaging modalities are the current standard for diagnosis. Of these, US is the most widely available, does not use ionizing radiation, and has the simultaneous ability to diagnose pelvic varicose veins, assess for physiologic venous reflux, and to map potential pelvic escape points in real-time.

Generalized imaging evaluation of CPP typically starts with transabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound, which can help identify abnormalities that exclude venous origin pelvic pain. In 2011, clinical practice guidelines from the American Venous Forum (Society of Vascular Surgery) recommended initial evaluation with duplex US (level 1A evidence). 38 The exam is ideally performed with the patient in a fasting state to reduce overlying/intervening bowel gas. The IVC, LRV, iliac veins, ovarian/gonadal veins, trans/periuterine veins, and tributaries of the IIVs are examined. In the majority of patients, the LRV crosses between the SMA and the aorta; however, in 2% it has a retroaortic course between the aorta and the spine. The presence and degree of obstruction is determined by a narrow aortomesenteric angle, the presence of collateral veins, prestenotic dilation, increased velocity ratio, slow or absent flow, and flow diversion to the left OV. 39 The left OV anatomy is widely variable in its number of trunks, their interconnection, and its termination. Lechter et al showed the left OV to originate from one to six trunks in the pelvis, and as they ascend merge to form fewer trunks. The classical single terminal trunk of the left OV at its confluence with the LRV is present in approximately 80% of veins studied. 40 If not present at baseline, OV reflux may be elicited by compression near the iliac fossa or a Valsalva maneuver. The right OV inflow into the IVC is typically found just above and right of the umbilicus, though it can rarely terminate in the right renal vein. When examining the trans/periuterine veins, if no reflux is visualized in pelvic varices arising from the uterine plexus, the exam can be repeated in the standing position with the US probe in the perineal space. 39 Potential connections from venous structures in the pelvic floor are also examined in the standing position.

Gonadal vein reflux has been found in 100% of patients with symptomatic pelvic varicosities, compared with in 25% of controls. 41 US also gives the operator the ability to investigate pelvic veins in various positions or with Valsalva, which can affect the ability to detect pelvic venous pathology. 17

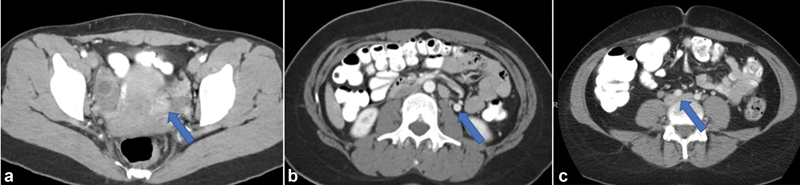

Given the typical population of patients with CPP, CT is not preferred secondary to its use of ionizing radiation and lack of time resolution. In patients who are unable to obtain authorization for a pelvic MRI, it may be useful in distinguishing PeVD from other causes of CPP based on the presence and diameter of pelvic varices. CTV may also be helpful in cases of suspected PeVD where the primary obstruction involves the CIV or external iliac vein (EIV). 42 CT may also be performed in the evaluation of these patients by other providers allowing for identification of pelvic varicosities, dilated and refluxing OVs, or iliac vein compression ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT images demonstrating ( a ) left periovarian varices (arrow), ( b ) dilated left ovarian vein with retrograde flow of contrast (arrow), and ( c ) left common iliac vein compression by the overlying right common iliac artery (arrow).

MRI is a superlative tool in the investigation of CPP; however, due to its high cost and relatively limited availability, it is typically reserved for when US is inadequate or unrevealing. MRI has very high tissue contrast, and can provide insight into both venous and nonvenous causes of CPP. Time resolved, contrast-enhanced MRI sequences have been shown to be accurate in evaluating the caliber of pelvic veins and the presence of reflux within the main pelvic veins, as well as match decrease or reversal of ovarian flow velocities. 43 44 These parameters have high sensitivities for OV (88%), IIVs (100%), and pelvic plexus (91%) insufficiency. 45 The UIP consensus guidelines mention MRV as a valuable tool for evaluating pelvic varices thought to be the result of obstructive pathologies in the LRV or CIVs. 46

SVP Classification

A multidisciplinary working group sponsored by the American Vein and Lymphatic Society (AVLS) proposed a clinical classification scheme based on symptoms, varices, and anatomy/pathophysiology. The system is not yet validated by clinical outcomes, but offers an accepted way to standardize the description of PeVD that later can be used to improve clinical decision making, develop disease-specific outcome measures, and identify homogenous patient populations for further research/trials ( Table 1 ). 17

Table 1. Summary of PeVD classification proposed by the AVLS working group.

| Symptoms | Varices | Physiologic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomy | Hemodynamics | Thrombosis | ||

|

S

0

No Symptoms

S 1 Renal Symptoms of VO S 2 CPP of VO S 3 EPS of VO a Localized symptoms associated with veins of external genitalia b Localized symptoms associated with pelvic origin non saphenous veins of the leg c Venous Claudication |

V

0

No Varices

V 1 Renal Hilar Varices V 2 Pelvic Varices V 3 Pelvic Origin Extra-Pelvic Varices a Genital Varices b Pelvic origin lower extremity varicose veins arising from pelvic escape points and extending onto the thigh |

|||

| IVC Inferior Vena Cava LRV Left Renal Vein L/R/B OV Ovarian Vein L/R/B CIV Common Iliac Vein L/R/B EIV External Iliac Vein L/R/B IIV Internal Iliac Vein PELV Pelvic Escape Veins |

Obstruction (O) or Reflux (R) |

Thrombotic (T) or Non-Thrombotic (NT) or Congenital (C) |

||

| *Any lower extremity venous insufficiency should additionally be classified according CEAP* |

KEY

VO = Venous Origin L/R/B = Left/Right or Bilateral CPP = Chronic Pelvic Pain EPS = Extra-Pelvic Symptoms |

|||

Treatments

Given the broad, diverse origins of CPP, interdisciplinary care including input from gynecology, medical management, pain education, physiotherapy, and psychological therapies showed improvements in pain severity, quality of life, and heath care utilization. 47 Some evidence suggests that there may be similar outcomes in improvement of pain and depression between surgically and medically managed patients across all etiologies, as was found in a practice specializing in chronic pain. 48

When there is a high clinical suspicion that pelvic source PeVD contributes to or may be the source of the patient's CPP, mechanical embolization with or without sclerotherapy is the current treatment of choice. 49 50 51

The technical aspects of the procedures to treat PeVD are widely variable. Typically, these procedures are done under local anesthesia and moderate sedation, and the patients are discharged on the same day as the procedure. Usually the right internal jugular vein or common femoral vein is accessed, and a catheter is used to select the LRV over a hydrophilic guidewire. Venography may be performed to assess for the origin of the left OV. Once catheterized, venography is performed in the left OV to assess for anatomy, physiology, and safety concerns prior to embolization. The catheter or sheath is then advanced more distally in the target pelvic vein. Venography may be repeated. Sclerosis is usually performed from this point at the discretion of the operator. Potential sclerosis agents include 5% sodium morrhuate, sodium tetradecyl sulphate, or polidocanol, which are typically prepared as a foam or slurry. 50 52 53 Sodium tetradecyl sulfate is the sclerosant of choice at the current time. Mechanical embolization follows with metallic coils, vascular plugs, or less frequently a liquid polymerizing agent such as cyanoacrylate or ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer. 54 Coils or plugs are typically oversized by up to 20% to account for possible spasm or hydration status and prevent central migration. This is then repeated in other major pelvic veins at the operator's discretion. Several factors play into the operator's choice of embolic material, such as concerns regarding artifact creation on future imaging and fluoroscopy time (given the demographics of the typical patient population). Guirola et al found that the use of plugs rather than coils decreased intervention time and, correspondingly, radiation dose. 55 To our knowledge, there are no definitive studies showing a clinical benefit of one embolic agent over another at this time.

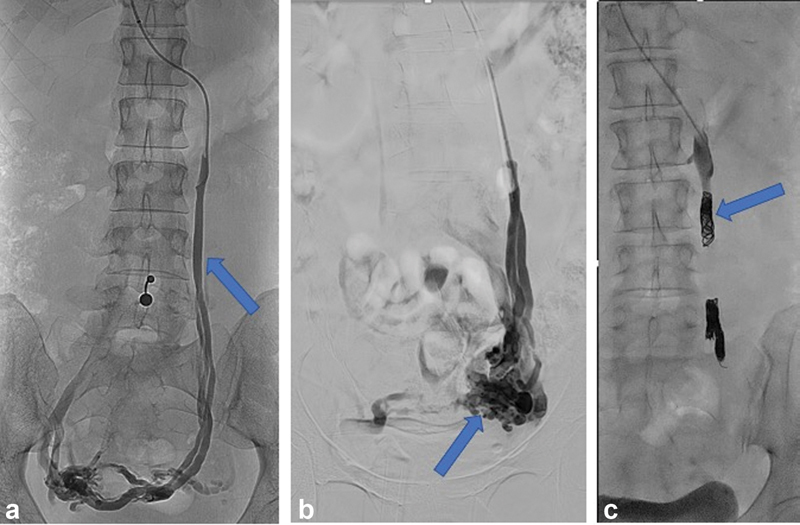

There is little consensus regarding how many of the main pelvic veins should be treated in one session, and/or in total. Some authors propose a limited, stepwise approach by first treating the left or bilateral OVs. 49 56 57 Other authors recommend complete treatment of all four main pelvic veins, namely, the left ovarian vein (LOV), right ovarian vein (ROV), left internal iliac vein (LIIV), and right internal iliac vein (RIIV) and may advocate including closure of communicating veins to the lower limb or gluteal veins. 14 51 52 55 58 59 Although publications exist describing coil embolization of the IIV, caution should be made prior to placement of coils in this component of the pelvic venous anatomy due to concerns of coil migration from this specific location. Fig. 3 shows an example of left OV embolization.

Fig. 3.

Fluoroscopic images demonstrate ( a ) left ovarian venography showing retrograde flow in the left ovarian vein (arrow) and filling of periovarian varices. ( b ) Balloon occlusion venography of the left ovarian vein shows left periovarian varices (arrow). ( c ) Fluoroscopic image showing occlusive coils in the left ovarian vein (arrow).

Outcomes

The initial technical success of the procedure has been reported between 84 and 100%. 50 51 60 Clinical outcomes of embolization, with or without sclerotherapy, are correspondingly positive, with symptom improvement ranging from 30 to 100%. Pain, as measured on a visual analog scale, decreased early and substantially in 75% of women, which generally increased over time and was sustained. Despite technical success, a clinical failure rate has been proposed between 6 and 32%. 53 This fluctuation may be related to the number of vessels examined or treated, treatment technique, and how outcomes were assessed. 61 62 Recurrence rates have been cited at between 7 and 20% at 1 year. 49 51 58 After 5 years, the literature is disparate, with recurrence rates ranging from 5 to 93%. 60 The patients who do recur, however, are typically amenable to repeat embolization with good clinical relief. 60 Management of nonthrombotic iliac vein compression may be another solution in these patients with recurrence that will be evaluated in future research studies.

Many of the women treated for PeVD are of childbearing age; however, robust data regarding fertility following embolization is not available. Liu et al provided a 12-patient series of women who underwent pelvic vein embolization as treatment for infertility thought to be related to PeVD, and all of the women subsequently had successful pregnancies. Additionally, no significant changes in luteinizing hormone or follicle-stimulated hormone were observed after embolization of pelvic varicose veins. 52 63 64

Complications

Overall complication rates for pelvic vein embolization are low. Minor complications including access-site hematoma, OV perforation, and low back pain can be seen in up to 11% of patients. Major complications, including migration of deployed embolic material to the lung or LRV, are less common at up to 2%. 60 Central migrations are most likely to occur from embolic agents deployed within the IIVs. 65 Patients commonly report brief periods of increased pelvic pain following embolization and the utilization of sclerosant in the pelvic reservoir, which can be easily managed with postprocedure pain medication.

Conclusion

PeVD is a common cause of CPP in women which should be considered when pelvic varicosities are identified. A proposed set of criteria for identifying patients with venous origin CPP can include pain for greater than 6 months, the presence of pelvic varicosities measuring at least 5 mm diameter, OV diameter greater than 6 mm with reflux, or significant left CIV compression. Once venous origin CPP is suspected, clinical success exists with both OV embolization and iliac vein stenting, but data are limited. Further data collection is in progress to identify specific symptoms of patients with venous origin CPP and will help guide patient selection. Randomized controlled trials of OV embolization and iliac vein stenting are also in progress to be performed in the near future.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Disclosures

R.S.W.: BD/Bard, Cordis, Inari Medical, Medtronic, Mentice, Tactile Medical.

References

- 1.Khilnani N M, Meissner M H, Learman L A. Research priorities in pelvic venous disorders in women: recommendations from a multidisciplinary research consensus panel. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(06):781–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gynecology Data Definitions; Revitalize GynecologyAmerican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Revised November 19, 2018. Accessed October 24, 2022 at:https://www.acog.org/practice-management/health-it-and-clinical-informatics/revitalize-gynecology-data-definitions

- 3.Ahangari A. Prevalence of chronic pelvic pain among women: an updated review. Pain Physician. 2014;17(02):E141–E147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathias S D, Kuppermann M, Liberman R F, Lipschutz R C, Steege J F. Chronic pelvic pain: prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(03):321–327. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zondervan K T, Yudkin P L, Vessey M P, Dawes M G, Barlow D H, Kennedy S H. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1149–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamieson D J, Steege J F. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(01):55–58. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zondervan K T, Yudkin P L, Vessey M P. Chronic pelvic pain in the community–symptoms, investigations, and diagnoses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(06):1149–1155. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.112904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steege J F, Metzger D A, Levy B S. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1998. Chronic Pelvic Pain: An Integrated Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard F M. The role of laparoscopy in chronic pelvic pain: promise and pitfalls. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48(06):357–387. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies L, Gangar K F, Drummond M, Saunders D, Beard R W. The economic burden of intractable gynaecological pain. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;12 02:S54–S56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips D, Deipolyi A R, Hesketh R L, Midia M, Oklu R. Pelvic congestion syndrome: etiology of pain, diagnosis, and clinical management. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(05):725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beard R W, Highman J H, Pearce S, Reginald P W.Diagnosis of pelvic varicosities in women with chronic pelvic pain Lancet 19842(8409):946–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beard R W, Reginald P W, Wadsworth J. Clinical features of women with chronic lower abdominal pain and pelvic congestion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95(02):153–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scultetus A H, Villavicencio J L, Gillespie D L, Kao T C, Rich N M. The pelvic venous syndromes: analysis of our experience with 57 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36(05):881–888. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.129114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoshi R KN, Lakhanpal S, Satwah V, Lakhanpal G, Malone M, Pappas P J. Iliac vein stenosis is an underdiagnosed cause of pelvic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(02):202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daugherty S F, Gillespie D L. Venous angioplasty and stenting improve pelvic congestion syndrome caused by venous outflow obstruction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(03):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meissner M H, Khilnani N M, Labropoulos N. The symptoms-varices-pathophysiology classification of pelvic venous disorders: a report of the American Vein & Lymphatic Society International Working Group on Pelvic Venous Disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(03):568–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kachlik D, Pechacek V, Musil V, Baca V. The venous system of the pelvis: new nomenclature. Phlebology. 2010;25(04):162–173. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2010.010006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemasle P, Greiner M. Duplex ultrasound investigation in pelvic congestion syndrome: technique and results. Phlebolymphology. 2017;24:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S J, Lim J W, Ko Y T. Diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome using transabdominal and transvaginal sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(03):683–688. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steenbeek M P, van der Vleuten C JM, Schultze Kool L J, Nieboer T E. Noninvasive diagnostic tools for pelvic congestion syndrome: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(07):776–786. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray H R, Carter H V, Pick T P, Howden R. 15th ed. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble; 2010. Gray's Anatomy (Barnes & Noble Collectible Editions) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauppila A. Uterine phlebography with venous compression. A clinical and roentgenological study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1970;3 03:3, 1–66. doi: 10.3109/00016347009155062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gagne P J, Tahara R W, Fastabend C P. Venography versus intravascular ultrasound for diagnosing and treating iliofemoral vein obstruction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5(05):678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raju S, Kirk O, Davis M, Olivier J. Hemodynamics of “critical” venous stenosis and stent treatment. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2014;2(01):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzger P B, Rossi F H, Kambara A M. Criteria for detecting significant chronic iliac venous obstructions with duplex ultrasound. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2016;4(01):18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chronic Pelvic Pain Working Group ; SOGC . Jarrell J F, Vilos G A, Allaire C. Consensus guidelines for the management of chronic pelvic pain. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27(08):781–826. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soysal M E, Soysal S, Vicdan K, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of goserelin and medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of pelvic congestion. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(05):931–939. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stratton P, Berkley K J. Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: translational evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(03):327–346. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.As-Sanie S, Kim J, Schmidt-Wilcke T. Functional connectivity is associated with altered brain chemistry in women with endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain. J Pain. 2016;17(01):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bagarinao E, Johnson K A, Martucci K T. Preliminary structural MRI based brain classification of chronic pelvic pain: a MAPP network study. Pain. 2014;155(12):2502–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pezzone M A, Liang R, Fraser M O. A model of neural cross-talk and irritation in the pelvis: implications for the overlap of chronic pelvic pain disorders. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(07):1953–1964. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malykhina A P. Neural mechanisms of pelvic organ cross-sensitization. Neuroscience. 2007;149(03):660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.As-Sanie S, Harris R E, Harte S E, Tu F F, Neshewat G, Clauw D J. Increased pressure pain sensitivity in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(05):1047–1055. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a7e1f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.International Pelvic Pain Society Website Accessed October 3, 2022 at:www.pelvicpain.org

- 36.Herrera-Betancourt A L, Villegas-Echeverri J D, López-Jaramillo J D, López-Isanoa J D, Estrada-Alvarez J M. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical findings for the diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome in women with chronic pelvic pain. Phlebology. 2018;33(05):303–308. doi: 10.1177/0268355517702057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson K, Minjarez R, Ferris B. Clinical presentation of women with pelvic source varicose veins in the perineum as a first step in the development of a disease-specific patient assessment tool. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5(04):493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Society for Vascular Surgery American Venous Forum Gloviczki P, Comerota A J, Dalsing M C.The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum J Vasc Surg 201153(5, Suppl):2S–48S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labropoulos N, Jasinski P T, Adrahtas D, Gasparis A P, Meissner M H. A standardized ultrasound approach to pelvic congestion syndrome. Phlebology. 2017;32(09):608–619. doi: 10.1177/0268355516677135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lechter A, Lopez G, Martinez C, Camacho J. Anatomy of the gonadal veins: a reappraisal. Surgery. 1991;109(06):735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malgor R D, Adrahtas D, Spentzouris G, Gasparis A P, Tassiopoulos A K, Labropoulos N. The role of duplex ultrasound in the workup of pelvic congestion syndrome. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2014;2(01):34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuo Y S, Chen C J, Chen J J. May-Thurner syndrome: correlation between digital subtraction and computed tomography venography. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114(04):363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dick E A, Burnett C, Anstee A, Hamady M, Black D, Gedroyc W M. Time-resolved imaging of contrast kinetics three-dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance venography in patients with pelvic congestion syndrome. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(994):882–887. doi: 10.1259/bjr/82417499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meneses L Q, Uribe S, Tejos C, Andía M E, Fava M, Irarrazaval P. Using magnetic resonance phase-contrast velocity mapping for diagnosing pelvic congestion syndrome. Phlebology. 2011;26(04):157–161. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2010.010049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asciutto G, Mumme A, Marpe B, Köster O, Asciutto K C, Geier B. MR venography in the detection of pelvic venous congestion. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36(04):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antignani P L, Lazarashvili Z, Monedero J L. Diagnosis and treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: UIP consensus document. Int Angiol. 2019;38(04):265–283. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.19.04237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allaire C, Williams C, Bodmer-Roy S. Chronic pelvic pain in an interdisciplinary setting: 1-year prospective cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(01):1140–1.14E14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamvu G, Williams R, Zolnoun D.Long-term outcomes after surgical and nonsurgical management of chronic pelvic pain: one year after evaluation in a pelvic pain specialty clinic Am J Obstet Gynecol 200619502591–598., discussion 598–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Venbrux A C, Chang A H, Kim H S.Pelvic congestion syndrome (pelvic venous incompetence): impact of ovarian and internal iliac vein embolotherapy on menstrual cycle and chronic pelvic pain J Vasc Interv Radiol 200213(2, Pt 1):171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez A J. Female pelvic vein embolization: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(04):806–820. doi: 10.1007/s00270-015-1074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laborda A, Medrano J, de Blas I, Urtiaga I, Carnevale F C, de Gregorio M A. Endovascular treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: visual analog scale (VAS) long-term follow-up clinical evaluation in 202 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(04):1006–1014. doi: 10.1007/s00270-013-0586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim H S, Malhotra A D, Rowe P C, Lee J M, Venbrux A C.Embolotherapy for pelvic congestion syndrome: long-term results J Vasc Interv Radiol 200617(2, Pt 1):289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Champaneria R, Shah L, Moss J. The relationship between pelvic vein incompetence and chronic pelvic pain in women: systematic reviews of diagnosis and treatment effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(05):1–108. doi: 10.3310/hta20050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcelin C, Izaaryene J, Castelli M. Embolization of ovarian vein for pelvic congestion syndrome with ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx ® ) . Diagn Interv Imaging. 2017;98(12):843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guirola J A, Sánchez-Ballestin M, Sierre S, Lahuerta C, Mayoral V, De Gregorio M A. A randomized trial of endovascular embolization treatment in pelvic congestion syndrome: fibered platinum coils versus vascular plugs with 1-year clinical outcomes. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(01):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maleux G, Stockx L, Wilms G, Marchal G. Ovarian vein embolization for the treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: long-term technical and clinical results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(07):859–864. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Capasso P, Simons C, Trotteur G, Dondelinger R F, Henroteaux D, Gaspard U. Treatment of symptomatic pelvic varices by ovarian vein embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1997;20(02):107–111. doi: 10.1007/s002709900116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whiteley A M, Holdstock J M, Whiteley M S. Symptomatic recurrent varicose veins due to primary avalvular varicose anomalies (PAVA): a previously unreported cause of recurrence. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2018;6:X18777166. doi: 10.1177/2050313X18777166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monedero J L, Ezpeleta S Z, Perrin M. Pelvic congestion syndrome can be treated operatively with good long-term results. Phlebology. 2012;27 01:65–73. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2011.012s03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winokur R S, Desai K R, Khilnani N M. Comment on pelvic venous disorders in women due to pelvic varices: treatment by embolization: experience in 520 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021;32(05):763–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meissner M H, Gibson K.Clinical outcome after treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: sense and nonsense Phlebology 201530(1, Suppl):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asciutto G, Asciutto K C, Mumme A, Geier B. Pelvic venous incompetence: reflux patterns and treatment results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38(03):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tarazov P, Prozorovskij K, Rumiantseva S. Pregnancy after embolization of an ovarian varicocele associated with infertility: report of two cases. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2011;17(02):174–176. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.2716-09.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dos Santos S J, Holdstock J M, Harrison C C, Whiteley M S. Long-term results of transjugular coil embolisation for pelvic vein reflux - results of the abolition of venous reflux at 6-8 years. Phlebology. 2016;31(07):456–462. doi: 10.1177/0268355515591306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marsh P, Holdstock J M, Bacon J L, Lopez A J, Whiteley M S, Price B A. Coil protruding into the common femoral vein following pelvic venous embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31(02):435–438. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]