Abstract

Traumatic injury to the large, central venous vasculature, although rare, is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Conventional open surgical treatment by repair or ligation can be technically challenging in anatomically difficult areas to expose. Furthermore, open surgical approach can release tension on the venous injury and result in uncontrollable bleeding. Endovascular techniques such as stenting and embolization can be used effectively for the treatment of traumatic venous injury. This article will discuss the morbidity and mortality associated with traumatic venous injuries, venous anatomy, endovascular treatment options, and management of traumatic venous injury.

Keywords: venous trauma, stenting, hemorrhage, interventional radiology

Traumatic injury to the large, central venous vasculature is rare but associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Conventional open surgical treatment by repair or ligation can be challenging and mortality is a direct function of anatomic location. This is the result of perilous exposure of the anatomy as well as inherent technical limitations of open surgical approaches (e.g., the release of tension on the venous injury and consequential uncontrollable bleeding). To address this challenge, endovascular techniques have been devised to overcome these limitations. These strategies including stenting and embolization have demonstrated their utility in the treatment of traumatic venous injury. This article will discuss the morbidity and mortality associated with traumatic venous injuries, venous anatomy, endovascular treatment options, and management of traumatic venous injury for four major venous structures: superior vena cava (SVC), inferior vena cava (IVC), iliac veins, and portal vein.

Superior Vena Cava

SVC Traumatic Injury

SVC traumatic injury is exceedingly rare with few available published data, as patients often expire shortly following trauma. SVC traumatic injury is more often the result of penetrating rather than blunt trauma, and iatrogenic injury is known to occur in the setting of central venous catheter or stent placement or during balloon angioplasty for stenoses. 1 2 3 Due to its relative mobility, the superior cavoatrial junction is the site most commonly affected by SVC trauma and can result in a contained mediastinal hematoma. Furthermore, the segment of the SVC approximately 3.5 cm above the right atrium is incompletely covered by the pericardium and injury to this segment can result in hemopericardium with associated tamponade physiology. 1 2 3

The absence of pericardial tamponade and contrast extravasation on CT angiography imaging are suggestive of relative hemodynamic stability, indicating that such patients may be managed conservatively. 4 Temporary balloon occlusion and stent graft placement have been reported for the management of iatrogenic rupture of the SVC. 4 Alternatively, open surgical repair by median sternotomy is required for patients unable to undergo endovascular repair.

SVC aneurysm is an extremely rare entity that may manifest as posttraumatic or postoperative sequelae. 5 6 There are two major types of aneurysms: saccular and fusiform with the latter being more common. There is no consensus for the management of SVC aneurysms. However, the saccular type is most often treated by surgical resection to minimize the risk of complications, such as rupture, thrombus formation with or without pulmonary thromboembolism, and mass effect or compression of surrounding structures. Endovascular treatment for saccular SVC aneurysms by stenting has been reported. 7 As the risk of complication of fusiform aneurysms is relatively low, these are more often managed conservatively.

Inferior Vena Cava

Inferior Vena Cava Blunt and Penetrating Trauma

IVC trauma is among the rarest and most fatal injuries encountered in the evaluation of both penetrating and blunt injuries. Despite its long course, the IVC is protected anteriorly by the liver and is centrally located within the abdomen, which likely contributes to the rarity of this type of injury. Nonetheless, an estimated 30 to 50% of patients with IVC trauma expire before reaching a healthcare facility and in-hospital mortality is greater than 60%. 8 9 10 Mortality rates for IVC injury have been reported to be between 34 and 70%. 10 11 Blunt IVC injury is especially rare, occurring in 1 to 10% of blunt trauma patients. 12 Deceleration causes shear forces on vessels, including at the cavoatrial junction, the hepatic veins, and as the posterior attachments of the liver that are intimately associated with the IVC, which can quickly lead to rapid, uncontrollable exsanguination or cardiac tamponade. 13 It has been postulated that shearing forces present in blunt trauma specifically (vs. penetrating trauma), such as flexion, stretching, and twisting may contribute to larger and more irregular lacerations that result in active extravasation and vascular contour abnormalities ( Fig. 3 ). 14

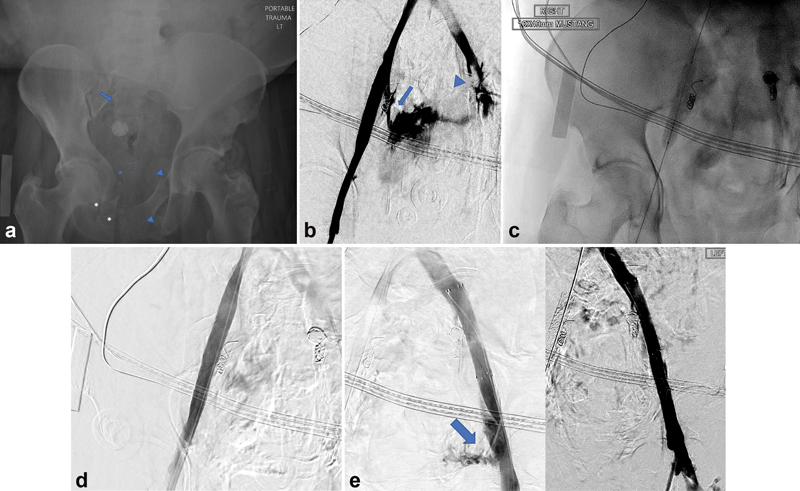

Fig. 3.

A 68-year-old female presented as a trauma after she was pinned against a garage door by motor vehicle with a 10-minute extrication time. ( a ) Pelvic X-ray demonstrates extensive comminuted and displaced pelvic ring including fractures of the right superior and inferior pubic rami (asterisks), right-sided acetabular wall (thin arrow), right sacral ala (block arrow), left ilium, and left superior and inferior pubic rami (arrow heads). ( b ) Pelvic venogram demonstrates transection of the right internal iliac vein (arrow) and left internal and external iliac veins (arrowhead) with active extravasation. ( c ) Balloon tamponade of the area of venous injury was performed for temporary hemostasis as a covered stent is being prepped for deployment across the injury. ( d ) Successful deployment of a covered stent within the common and external iliac artery, across the ostium of the transected right internal iliac vein. No evidence of contrast extravasation. ( e ) A covered stent was placed in the common and proximal external iliac artery, across the ostium of the transected left internal iliac vein. Left: After the stent placement, note was made of focal extravasation arising from the distal external iliac artery (blue arrow). Right: An additional covered stent was deployed across the area of injury resulting in cessation of extravasation.

IVC Traumatic Injury: Anatomy

The IVC can be anatomically divided into five sections: infrarenal, pararenal, suprarenal, retrohepatic, and suprahepatic. The majority of injuries occur in the infrarenal segments (39%), followed by pararenal (17%), suprarenal (18%), retrohepatic (19%), and suprahepatic (2–10%). 9 The infrarenal segment extends from the confluence of the common iliac veins to the renal veins. The suprarenal segment extends between the renal and hepatic veins. This segment can be further described as infrahepatic versus retrohepatic. The infrahepatic segment extends between the inferior edge of the liver and the confluence of the renal veins. The retrohepatic segment lies behind the liver. Lastly, the suprahepatic extends between the hepatic veins and the right atrium.

IVC Traumatic Injury: Morbidity and Mortality

Mortality has been associated with the location of IVC injury, which can reach rates of 100% for suprahepatic, 78% for retrohepatic, and 33% for suprarenal injuries. 15 Distance of the injury from the heart therefore serves as a strong prognostic factor. Anatomic and technical factors likely account for these differences in mortality rate. 16 Access to the suprahepatic IVC requires division of the falciform ligament, radical hepatic mobilization, mobilizing the damaged segment of the IVC, and extending the initial laparotomy incision into a full sternotomy, all of which are associated with extremely high mortality rates. 16 17 Mortality is further compounded by perioperative and long-term complications, including IVC stenosis and thrombosis. 17 Prosthetic vascular repair is also burdened by higher mortality rates. 16 In contrast to suprahepatic traumatic injuries, infrarenal IVC blunt injury is associated with the lowest mortality rate (23%). 16 The relatively lower mortality rate of infrarenal injuries has been attributed to the accessibility of the caval bifurcation zone. While division of the right common iliac artery is required for exposure, this is a more familiar area for vascular surgeons, relative to other segments of the IVC. Furthermore, injuries of this location are more commonly repaired by venorrhaphy.

Furthermore, trauma to the IVC is frequently associated with liver injury in blunt trauma. Injury to the juxtahepatic veins is a rare but fatal occurrence with mortality rates between 50 and 80% with most deaths caused by exsanguination. 18

Penetrating trauma most frequently entail gunshot wounds and stab wounds. The majority of IVC injuries are the result of penetrating trauma (86 vs. 14% for blunt trauma) ( Fig. 1 ). 9 The reported mortality rates between penetrating and blunt injury are mixed, with some showing increased mortality for one type of injury over the other and others showing no significant difference. 9 14 15 Patients of penetrating trauma most frequently expire secondary to uncontrollable hemorrhage and cardiac arrest in the emergency department or operating room. 9

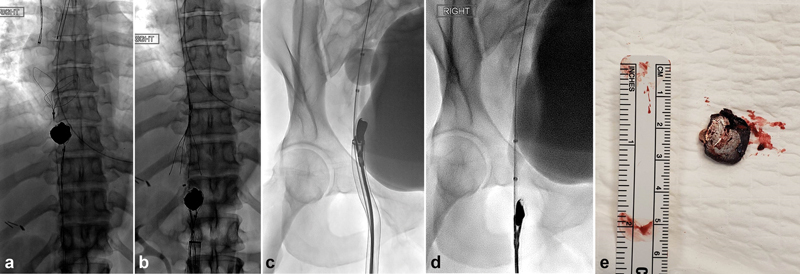

Fig. 1.

A combined endovascular and open surgical approach was implemented to retrieve a dominant 2-cm ballistic fragment lodged near the inferior cavoatrial junction in a 39-year-old female with a gunshot wound to the upper abdomen. ( a ) Two 35-mm snares were positioned superiorly and inferior to the ballistic fragment within the inferior vena cava (IVC). The inferior snare was used to retract the ballistic fragment toward the right femoral vein access site. The superior snare was used as a temporary measure to prevent ballistic embolization to the heart. ( b ) The ballistic fragment was retracted inferiorly into the infrarenal IVC. An IVC filter was then deployed as a permanent measure to prevent ballistic embolization. Attempts to remove the ballistic fragment via ( c ) rigid forceps and ( d ) Fogarty embolectomy balloon were unsuccessful. ( e ) The ballistic fragment was removed by surgical cutdown with primary vein closure. Postoperatively, the patient developed extensive right lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) secondary to trauma imposed by the retracted ballistic fragment against the vein wall. Management included fasciotomy, skin grafting, and iliofemoral DVT thrombectomy.

IVC Traumatic Injury: Noninvasive Imaging Techniques by CT Venography

CT is the mainstay imaging modality in the evaluation of blunt and penetrating trauma but is limited to hemodynamically stable patients. In severe trauma, unstable patients are often not candidates for CT evaluation and instead require emergent laparotomy. The CT radiographic appearance of traumatic IVC injury is not well characterized due to the rarity of this injury and also because many of these patients are unstable for CT imaging.

Standard CT protocols in the evaluation of traumatic injuries focus on the evaluation of arterial vasculature and solid organs. On the other hand, the characterization of venous structures is limited by several factors, including hemodilution of contrast and renal elimination of contrast. To optimize the identification of trauma-related injuries, Holly and Steenburg detailed an intravenous contrast-enhanced CT protocol that includes the whole body (neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis) in the arterial phase. 19 Images of the abdomen and pelvis are also acquired following a 90-second delay (portal venous phase). While imaging during the portal venous phase aims to identify solid-organ injuries, venous opacification can also be seen and therefore may reveal injury to the venous structures. Delayed phase imaging, while not routinely acquired, can also be obtained if there is concern for renal collecting system injury.

CT evaluation of the trauma patient is invaluable, as the most significant characteristic elements of the injury and those with prognostic value can be readily visualized on CT imaging. These include segment of injury, proximity to the heart, and evidence of active extravasation. 9 Direct and indirect signs can indicate the presence of venous injury. Direct signs include thrombosis, vessel occlusion, avulsion or complete vascular tear, rupture, active extravasation, and pseudoaneurysm. 19 A common imaging pitfall is the misinterpretation of mixing artifact of unenhanced blood as thrombosis or vessel injury. 19 Extravasation of venous contrast on CT imaging may often be absent in the presence of venous injury and has been attributed to low caval pressure or tamponade from adjacent structures that reduce bleeding. 10

Indirect signs may manifest as perivascular hematoma, retroperitoneal hematoma, hemopericardium, fat stranding, intracaval fat, vessel contour irregularity, and intimal flap, which are nonspecific and not diagnostic of the presence of venous injury. 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Rarely, arteriovenous fistula may also be seen. 14 The surgical literature has described additional findings, including caval-renal artery fistula, complete transection of the IVC, and caval duodenal fistula. 14 Importantly, there is close association of IVC injury with severe hepatic injuries; therefore, the presence of injury to the liver or surrounding structures should prompt more vigilante inspection of the IVC in the absence of clear direct or indirect signs. 19

Compared with penetrating injuries, blunt injuries more likely demonstrate CT findings of primary vascular injury. Both active extravasation (83 vs. 33%) and vascular contour abnormalities (50 vs. 18%) were more commonly seen on CT imaging in blunt trauma than in penetrating trauma. 14 This difference has been attributed to the shearing forces that occur in blunt trauma that may lead to larger and more irregular lacerations that lead to active extravasation and vascular contour abnormalities. Shearing forces are notably present at the attachment sites of the IVC and liver, a commonly injured organ in blunt trauma, which likely further contributes to the frequency of these CT findings in blunt trauma. 14

Iliac Veins

Trauma to the iliac vessels comprises only 1.8 to 6.5% of all vascular injuries, 27 yet they are associated with a mortality rate between 55.6 and 100%. 28 Traditionally, open surgical treatment of iliac venous injury involved ligation or repair. Ligation is associated with greater morbidity (edema, pain, long-term sequelae of venous hypertension, deep vein thrombosis), while repair is more technically challenging. Furthermore, laparotomy reduces the tension effect of the iliac wing, which aids in the tamponade of active hemorrhage. In contrast, an endovascular approach allows direct coverage of the venous injury while maintaining the retroperitoneal tamponade effect. Covered stents 29 are the most commonly used device to treat traumatic iliac vein injury, although the use of uncovered stents 30 as well as occlusion balloons 31 have been reported.

Portal Veins

Portal Venous Trauma in the Setting of Portal Hypertension

The incidence of significant bleeding from portal venous injury is reportedly between 0.08 and 0.10%, 32 infrequent relative to the more common hepatic arterial injuries. This difference has been attributed to the low pressures of the portal venous system. However, the mortality rate associated with portal venous injury is high (57%), as this type of injury is commonly associated with severe injuries affecting adjacent organs. 32 33 34

A rarely reported occurrence, the presence of portal hypertension elevates the risk of mortality from portal venous injury. Coexisting risk factors, most notably in cirrhotic patients, include coagulopathy, varices, and splenomegaly, which complicate spontaneous cessation of bleeding.

In contrast to the management of hepatic arterial extravasation, treated primarily by embolization, the management of portal venous injury is complex and associated with high mortality rates. In hemodynamically stable patients, portal venography, portal vein reanastomosis, portocaval anastomosis, interposed graft placement, and intraoperative temporary stenting of the injury vasculature have been reported. 32 33 35 Endovascular treatment by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation has also been reported and may avoid operative mortality and morbidity associated with portal venography, as well as avoid the complications of increased mesenteric congestion caused by portal ligation. 36 However, these procedures are complicated by intraoperative exsanguination 37 and high mortality rates of up to 46.7%. 32 Acute portal vein ligation can be used as a last-line measure but is complicated by mesenteric congestion, systemic hypotension due to sequestration of venous return, and rarely bowel infarction. 38 Acute portal vein ligation is associated with a survival rate of 13%. 39 Importantly, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score is an important prognostic factor. 40 Patients with a MELD score of 17 or higher were predictive of postoperative mortality.

Principles of Systemic Venous Trauma Management

There are three general approaches to treating patients with venous trauma: observation with follow-up imaging, open surgical management, or endovascular therapy. Careful observation with follow-up imaging is appropriate in patients who are hemodynamically stable with findings suggestive of a self-limiting venous injury such as subtle fat stranding adjacent to the vein without contrast extravasation or large hematoma to suggest active hemorrhage. Intervention should be considered when patients with venous injury become hemodynamically unstable or there are significant associated injuries. An open surgical approach is preferred when there are significant injuries to solid organs or bowel necessitating exploratory laparotomy during which time venous injuries can be ligated or surgically repaired. Open surgical treatment of venous injury is either through ligation or venous repair. Potential complications related to ligation of major veins include long-term sequelae of venous hypertension, thrombosis, edema, and pain. Surgical venous repair can involve lateral venorrhaphy, placement of a vein patch, end-to-end anastomosis, or complicated grafts. 29 Furthermore, laparotomy can decrease the tamponade effect of a hematoma, resulting in uncontrolled bleeding.

An endovascular approach is most appropriate when a patient does not require operative management, but the venous injury still must be addressed. Endovascular approach should be considered in patients with venous injuries in anatomic areas that are difficult to expose via standard operative repair, increased risk of iatrogenic nerve injury, high risk of prolonged bleeding complications due to surgery, or those who are poor surgical candidates. 29 Depending on the nature of the injury and operator/institution preference, angioplasty, balloon tamponade, stent placement, or a combination of techniques may be used. Specifically, when there is early filling of the venous system secondary to arteriovenous fistula formation, embolization techniques may be used to close the fistulous connection. Fig. 1 demonstrates a combined multimodal endovascular and open surgical approach to retrieve a ballistic fragment lodged near the inferior cavoatrial junction.

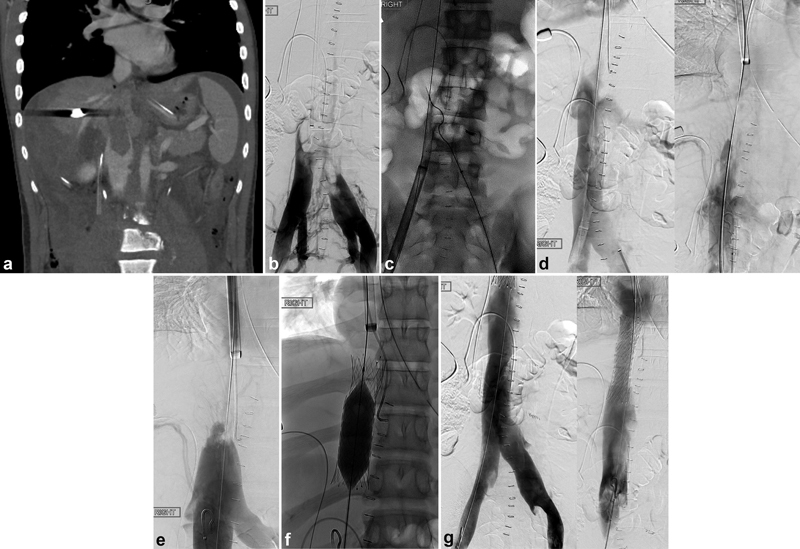

Prior to performing an endovascular treatment to vascular injury on a patient, careful evaluation of CTA imaging is recommended if available. Focusing on the venography in the areas correlating to the direct and indirect signs of venous vasculature injury seen on imaging is important to reduce procedural time and prevent prolonged bleeding. Additional traumatic sequelae can also be assessed on pretreatment imaging. Fig. 2 demonstrates an endovascular approach to the treatment of an extensive posttraumatic IVC thrombus in the setting of contraindication to thrombolysis. Furthermore, in patients with venous trauma, it is important to keep compressive binders in place to prevent ongoing venous hemorrhage throughout the procedure.

Fig. 2.

Endovascular recanalization of the inferior vena cava (IVC), thrombosed in the setting of trauma with contraindication to thrombolytic therapy. The patient sustained a gunshot wound to the right upper quadrant, requiring surgical repair of retrohepatic IVC injury and liver laceration as well as coil embolization of an actively bleeding lumbar artery. ( a ) Coronal contrast-enhanced and ( b ) IVC venogram demonstrated extensive thrombus of the IVC and hepatic veins. ( c ) Maceration via a rotational thrombectomy system was implemented for clot removal. ( d ) Post-thrombectomy venogram demonstrated patency of the treated segment of the IVC (inferior IVC, left; superior IVC, right), although ( e ) IVC stenosis was noted superiorly, secondary to repair. ( f ) Uncovered stents were deployed across the stenosed segment. ( g ) Post-stenting venogram confirmed patency of the entire IVC (inferior IVC, left; superior IVC, right).

Angiographic Technique

Access

Depending on the location of venous injury being interrogated, venous access can be obtained using femoral, internal jugular, or brachial veins. In the setting of trauma, access into the femoral vein can provide the fastest access into the IVC. Pelvic binders can obscure access to the femoral vein. It may be necessary to cut away portions of the pelvic binder to create a sufficient window. In the setting of hemorrhagic shock, the patient's femoral vein may be diminutive or collapsed.

Venography

An angiographic sheath can be inserted over the wire to secure access. A flush catheter should be advanced into the venous system at the area of suspected injury and a venocavogram should be obtained ( Fig. 3a, b ). A 5-Fr directional catheter and 0.035 guidewire can be used to select the focal area of venous injury and obtain a venogram. The selective venogram should be used to determine the correct size and length for a covered stent and/or embolic coils.

Intervention

Using guidewire and catheter manipulation, access should be obtained across the injured segment of the vein if possible. In patients who are rapidly exsanguinating, temporary control of hemorrhage can be achieved by inflating a balloon occlusion catheter proximal to the injury ( Fig. 3c ).

To perform endovascular exclusion of a venous injury, bilateral percutaneous femoral venous access can be obtained with large sheaths for occlusion balloon placement, venography, and placement of large stents. 30

As balloon occlusion–mediated hemostasis is achieved, the appropriate stents and/or coils can be prepared for a more definitive treatment. Traumatic injury to the large venous vasculature such as the SVC, IVC, or iliac veins can be treated by placing a covered stent across the area of injury ( Fig. 3d, e ). Of note, the diameter of the venous system is significantly larger than that of the arterial system. Additionally, the diameter of the IVC can be changed considerably during volume resuscitation. It is recommended to oversize covered stents by 20 to 25% and obtain a 30-mm sealing zone on both sides to achieve adequate hemostasis. Because the injured vein is more susceptible to tearing and more compliant to dilatation, a longer landing zone than is necessary to that of arterial stenting to ensure an adequate seal. 30 In the setting of juxtahepatic and retrohepatic IVC injuries, careful attention must be given to prevent stenting across the hepatic and renal veins and causing outflow obstruction. Injuries at the iliocaval confluence should be performed using kissing stent grafts or a large stent in the IVC and two kissing stents in the common iliac veins. The internal iliac artery outflow can be stented across without significant sequelae. At the conclusion of the case, the final venogram should demonstrate cessation of contrast extravasation.

Conclusion

Interventional radiology can offer an alternative and expeditious approach to treating traumatic venous injuries in cases that are challenging to treat using open surgical approach. Endovascular treatments such as coiling and stenting venous injury can reduce prolonged bleeding associated with surgical treatments.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Azizzadeh A, Pham M T, Estrera A L, Coogan S M, Safi H J. Endovascular repair of an iatrogenic superior vena caval injury: a case report. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(03):569–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brant J, Peebles C, Kalra P, Odurny A. Hemopericardium after superior vena cava stenting for malignant SVC obstruction: the importance of contrast-enhanced CT in the assessment of postprocedural collapse. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2001;24(05):353–355. doi: 10.1007/s002700001795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin M, Baumgartner I, Kolb M, Triller J, Dinkel H-P. Fatal pericardial tamponade after Wallstent implantation for malignant superior vena cava syndrome. J Endovasc Ther. 2002;9(05):680–684. doi: 10.1177/152660280200900520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabutey N-K, Rastogi N, Kim D. Conservative management of iatrogenic superior vena cava (SVC) perforation after attempted dialysis catheter placement: case report and literature review. Clin Imaging. 2013;37(06):1138–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panduranga P, Thomas E, Al-Maskari S, Al-Farqani A. Giant superior vena caval aneurysm in a post-Glenn patient. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14(06):878–879. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varma P K, Dharan B S, Ramachandran P, Neelakandhan K S. Superior vena caval aneurysm. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2003;2(03):331–333. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9293(03)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griviau L, Chevallier O, Favelier S, Pottecher P, Gehin S, Loffroy R. Endovascular management of a large aneurysm of the superior vena cava involving internal thoracic vein with remodeling technique. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2016;6(03):315–317. doi: 10.21037/qims.2016.06.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannakopoulos T G, Avgerinos E D. Management of peripheral and truncal venous injuries. Front Surg. 2017;4:46–46. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2017.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huerta S, Bui T D, Nguyen T H, Banimahd F N, Porral D, Dolich M O. Predictors of mortality and management of patients with traumatic inferior vena cava injuries. Am Surg. 2006;72(04):290–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Netto F ACS, Tien H, Hamilton P. Diagnosis and outcome of blunt caval injuries in the modern trauma center. J Trauma. 2006;61(05):1053–1057. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000241148.50832.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckman R F, Pathak A S, Badellino M M, Bradley K M. Injuries of the inferior vena cava. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81(06):1431–1447. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(01)80016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole K, Shadis R, Sullivan T R., Jr Retrohepatic hematoma causing caval compression after blunt abdominal trauma. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(01):48–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthees N G, Mankin J A, Kalinkin O M, Richardson R R. A rare opportunity for conservative treatment in a case of blunt trauma to the supradiaphragmatic inferior vena cava. J Surg Case Rep. 2013;2013(11):rjt092. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjt092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai R, Raptis C, Schuerer D J, Mellnick V M. CT appearance of traumatic inferior vena cava injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(04):705–711. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosengart M R, Smith D R, Melton S M, May A K, Rue L W., IIIPrognostic factors in patients with inferior vena cava injuries Am Surg 19996509849–855., discussion 855–856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piffaretti G, Carrafiello G, Piacentino F, Castelli P.Traumatic IVC injury repair: the endovascular alternative Endovasc Today. 2013(November):39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheaito A, Tillou A, Lewis C, Cryer H. Management of traumatic blunt IVC injury. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckman R F, Jr, Miraliakbari R, Badellino M M. Juxtahepatic venous injuries: a critical review of reported management strategies. J Trauma. 2000;48(05):978–984. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holly B P, Steenburg S D. Multidetector CT of blunt traumatic venous injuries in the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Radiographics. 2011;31(05):1415–1424. doi: 10.1148/rg.315105221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han B K, Im J-G, Jung J W, Chung M J, Yeon K M. Pericaval fat collection that mimics thrombosis of the inferior vena cava: demonstration with use of multi-directional reformation CT. Radiology. 1997;203(01):105–108. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hewett J J, Freed K S, Sheafor D H, Vaslef S N. Contained hematoma (pseudoaneurysm) of the inferior vena cava associated with blunt abdominal trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172(04):1144–1144. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.4.10587173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewett J J, Freed K S, Sheafor D H, Vaslef S N, Kliewer M A. The spectrum of abdominal venous CT findings in blunt trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(04):955–958. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.4.1760955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hines J, Katz D S, Goffner L, Rubin G D. Fat collection related to the intrahepatic inferior vena cava on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172(02):409–411. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parke C E, Stanley R J, Berlin A J. Infrarenal vena caval injury following blunt trauma: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17(01):154–157. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199301000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheafor D H, Foti T M, Vaslef S N, Nelson R C. Fat in the inferior vena cava associated with caval injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171(01):181–182. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.1.9648784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh S P, Canon C L, Treat R C, Crowe D R, O'Dell R H, II, Koehler R E. Traumatic dissection of the inferior vena cava. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168(01):253–254. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.1.8976954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattox K L, Feliciano D V, Burch J, Beall A C, Jr, Jordan G L, Jr, De Bakey M E.Five thousand seven hundred sixty cardiovascular injuries in 4459 patients. Epidemiologic evolution 1958 to 1987 Ann Surg 198920906698–705., discussion 706–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kataoka Y, Maekawa K, Nishimaki H, Yamamoto S, Soma K.Iliac vein injuries in hemodynamically unstable patients with pelvic fracture caused by blunt trauma J Trauma 20055804704–708., discussion 708–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smeets R R, Demir D, van Laanen J, Schurink G WH, Mees B ME. Use of covered stent grafts as treatment of traumatic venous injury to the inferior vena cava and iliac veins: a systematic review. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(06):1577–15870. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sofue K, Sugimoto K, Mori T, Nakayama S, Yamaguchi M, Sugimura K. Endovascular uncovered Wallstent placement for life-threatening isolated iliac vein injury caused by blunt pelvic trauma. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30(08):680–683. doi: 10.1007/s11604-012-0100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tillman B W, Vaccaro P S, Starr J E, Das B M. Use of an endovascular occlusion balloon for control of unremitting venous hemorrhage. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(02):399–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraga G P, Bansal V, Fortlage D, Coimbra R. A 20-year experience with portal and superior mesenteric venous injuries: has anything changed? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37(01):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henne-Bruns D, Kremer B, Lloyd D M, Meyer-Pannwitt U. Injuries of the portal vein in patients with blunt abdominal trauma. HPB Surg. 1993;6(03):163–168. doi: 10.1155/1993/74027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearl J, Chao A, Kennedy S, Paul B, Rhee P. Traumatic injuries to the portal vein: case study. J Trauma. 2004;56(04):779–782. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000053467.36120.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reilly P M, Rotondo M F, Carpenter J P, Sherr S A, Schwab C W. Temporary vascular continuity during damage control: intraluminal shunting for proximal superior mesenteric artery injury. J Trauma. 1995;39(04):757–760. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199510000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sundarakumar D K, Smith C M, Lopera J E, Kogut M, Suri R. Endovascular interventions for traumatic portal venous hemorrhage complicated by portal hypertension. World J Radiol. 2013;5(10):381–385. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i10.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jurkovich G J, Hoyt D B, Moore F A. Portal triad injuries. J Trauma. 1995;39(03):426–434. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pachter H L, Drager S, Godfrey N, LeFleur R. Traumatic injuries of the portal vein. The role of acute ligation. Ann Surg. 1979;189(04):383–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone H H, Fabian T C, Turkleson M L. Wounds of the portal venous system. World J Surg. 1982;6(03):335–341. doi: 10.1007/BF01653551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin B-C, Fang J-F, Wong Y-C, Hwang T-L, Hsu Y-P. Management of cirrhotic patients with blunt abdominal trauma: analysis of risk factor of postoperative death with the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score. Injury. 2012;43(09):1457–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]