Abstract

Background

The stigma associated with monkeypox (mpox) may prevent people from following recommended guidelines. Using a “model of stigma communication,” this study maps and determines the mpox stigma on Twitter among LGBTQ+ (Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and more) community.

Methods

The tweets that contained the terms ‘#monkeypox’, ‘#MPVS’, ‘#stigma’, and ‘#LGBTQ+’ and were published between May 01, 2022 and Sept 07, 2022 were extracted. For sentiment analysis, the VADER, Text Blob, and Flair analysers were implemented. This study evaluated the dynamics of stigma communication based on the “model of stigma communication”. A total of 70,832 tweets were extracted, from which 66,387 tweets were passed to the sentiment analyser and 3100 tweets were randomly selected for manual coding. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) criteria was adopted to report this study.

Findings

This research provided insight on the cause, communication, and patterns of mpox stigma in the LGBTQ+ community. In the community, stigmatisation was influenced by the group's labelling as the source of monkeypox. Some users believed that mpox resembled previously observed diseases such as HIV/AIDS, and COVID-19. Despite officials and media outlets disseminating information about preventing mpox and stigmatisation, a number of individuals failed to comply. The LGBTQ+ community faced peril in the form of violence due to escalating stigma. Misinformation and misinterpretation spread further stigmatisation.

Interpretation

This study indicates that authorities must address misinformation, stigmatization of the LGBTQ+ community, and the absence of a comprehensive risk-communication plan to improve the system. The effects of stigmatization on the vulnerable population must be handled in conjunction with a well-developed risk communication plan, without jeopardizing their wellbeing.

Keywords: Monkeypox, Mpox, Social Stigma, LGBTQ+, risk communication

1. Introduction

Monkeypox (Mpox), caused by an enveloped double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA) virus, has sporadically spread from animals to people since the 1970s, mostly in Western or Central Africa [1]. In 2017, the Niger Delta outbreak returned after 40 years. Mpox cases in non-endemic areas began in early May 2022 [2]. On July 23, 2022, WHO Director-General declared mpox a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) [3]. More than 82,809 confirmed cases have been reported globally as of December 16, 2022 [4]. The present outbreak of mpox has a number of unusual characteristics. In the UK and other non-endemic countries, a significant number of confirmed cases are homosexual, bisexual, or men who have sex with men (MSM). Heterosexual women account for 0.5% of cases [5]. Mpox is transmitted via direct contact with the infectious rash, scabs, or bodily fluids, including respiratory secretions, as well as by touching objects (such as clothing or linens) that have been in contact with the infectious rash or fluids. Mpox has been isolated from sperm, although it is unknown if it might be transmitted through sexual contact without causing rashes [6]. Therefore, the challenges surrounding the emergence of public health concerns are difficult and intricate because they have far-reaching implications not just in the medical, but also in the social, economic, political, and behavioural sectors [7].

With increased dependence on digital media platforms for health and related information, Twitter has been identified as a powerful tool for disseminating real time information to promote public awareness. Approximately, 2.95% of the world's population uses Twitter. Additionally the feedback mechanism on these platforms such as the responding comments help to gauge the public perception and civic mood [8]. Therefore data from social media sources can be analysed not only for syndromic surveillance but also to address public health related concerns and direct public perception using web based information. It may also be used to foster efficient communication among social media users and other platforms capable of countering conspiracy theories [6].

Examining evolving discussion regarding the outbreak are useful to determine the components that are informing public views. During COVID-19, Twitter data was utilized for scientific research to observe users' rising concerns, spread of misinformation, and overall sentiment [9]. With the development of web-based networking and social technologies, the widespread use of social media has expanded public participation in emergency response. Nonetheless, the qualities of severe ineffectiveness, irrationality, and uniformity are ascribed to public opinion extracted from social media. Despite these drawbacks it is understood that social media is essential to the social and technological framework that allows people to remain connected during emergencies as it has emerged as major platform for communication.

During outbreaks, individuals are advised to comply with guidelines to avoid contracting disease and minimize disease transmission, such as receiving medical care and alerting public health officials of their contacts [3]. In the emerging infectious diseases, social stigma has resulted in persons being labelled, stereotyped, discriminated against, treated separately, and/or experiencing a loss of status, which has a variety of detrimental repercussions on them. This weakens social cohesion, potentially leading to social isolation, and patients may refuse to disclose or underestimate the frequency or severity of their symptoms, making it more difficult to prevent a disease epidemic. Instances throughout HIV and COVID-19 have highlighted the negative consequences of stigma, such as failure to disclose the disease and medical noncompliance. It has also been observed to have detrimental effects on mental health, including an increase in depression, and substance abuse. Moreover, stigma has been linked to a decline in testing during outbreaks [[10], [11], [12]]. Due to the infectious nature of mpox, contact tracing is essential for assessing community spread. However, the stigma associated with mpox could inhibit individuals from adhering to recommended guidelines, such as discouraging people from seeking help or getting vaccinated. Therefore, reducing mpox stigma is crucial in order to control the spread of the disease.

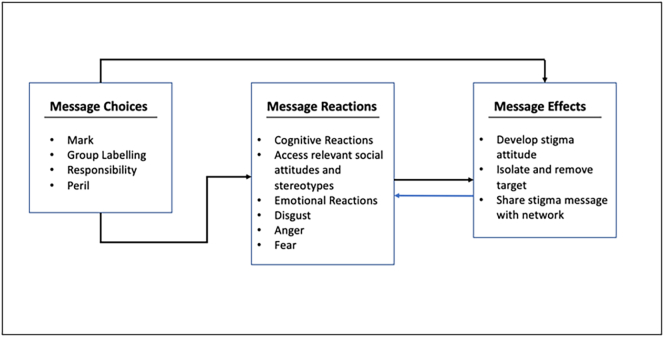

As mpox is gradually spreading throughout non-endemic nations and misinformation about mpox has begun to proliferate, public responses to mpox can be easily detected on social networks such as Twitter. In this context, we used the ‘model of stigma communication’ to understand the mpox stigma on Twitter among the high risk group, especially we explored the message content of stigma communication [13]. In the model, the message content is categorised into four content cues i.e. mark, group labelling, responsibility, and peril. These are essential for the development of stigma beliefs, the willingness to spread stigma messages, and the promotion of discrimination against stigmatised groups. Guided by the model of stigma communication, this research aims to map tweets into stigmatisation or non-stigmatization using a deep learning models, and then to determine themes of the mark, label, responsibility, and peril content of mpox related tweets in the LGBTQ+ community. In addition, to explore whether the presence of misinformation regarding mpox is linked to the existence of mpox stigma content. The study results would provide us with a more comprehensive view of public perceptions of mpox on Twitter, and would be instructive for more effective policy and health system response coordination, as well as designing tailored risk-communication initiatives.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data acquisition and pre-processing

Twitter's academic research API v2, which searches against a sample of tweets published since May 2022 was used for data collection [14]. In a series of consecutive searches, tweets that (a) contained the terms ‘#monkeypox’, ‘#MPVS’, ‘#stigma’, ‘#LGBTQ+’ (b) were published between 2022/05/01 and 2022/09/07 were collected.

Several processes were performed to prepare tweets for analysis: (1) Duplicates were eliminated in two stages. First, duplicates were detected by inspecting each tweet's ‘is retweet’ label provided by Twitter. Second, Pandas library was used to remove additional duplicates based on tweet id and content; (2) cleaning of tweets was performed as follows: (a) removed URL's, email, hashtags, mentions, and digits for VADER and TextBlob analysers, (b) converted tweets to lower case, mapped emojis (and emoticons) to their corresponding text, removed punctuations and stop-words for Flair analyser [15,16]. (c) removed tweets having less than 5 words since some of the tweets had only URL's, and some had very few words after pre-processing step which would not contribute to analysis. (3) We restricted the tweets to “English” language.

Data obtained in this study were made publicly available by Twitter users and are thus deemed public domain data. By presenting data in aggregated form, user anonymity was maintained. As a result, no additional ethical approval was considered necessary for this research. This study's data usage and processing followed Twitter's Terms of Service as well as the Developer's Agreement and Policy [17].

2.2. Data analysis

We have used NLP (Natural Language Processing) packages for sentiment analysis of un-labelled data: Lexicon (or Rule) based models, VADER and TextBlob, and embedding based model Flair [[18], [19], [20]]. TextBlob is a lexicon-based python library for Natural Language Processing (NLP), which returns the sentiment score of a sentence as tuple: Polarity and Subjectivity. The Polarity defines the sentiment or the opinion in the sentence whereas the Subjectivity (lies between [0, 1]) quantifies the amount of personal opinion and factual information contained in the text. High subjectivity score indicates that the text contains more personal opinion than the factual information [15]. VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary for sEntiment Reasoning) is another popular lexicon-based python package for performing NLP which uses a list of lexical features (e.g., word) which are marked as positive or negative according to their semantic direction to calculate the text sentiment. The output of VADER includes four scores as dictionary keys: compound score, positive (pos) score, negative (neg) score and neutral (neu) score. The pos, neg, and neu gives the percentage by how much the text is positive, negative or neutral [16]. The compound score measures the actual sentiment of the text. Both VADER and TextBlob return normalized polarity scores in the range [1-, 1], −1 being strongly negative and 1 being strongly positive as compound score for the given text. The continuous polarity scores are then transformed to discrete values, yielding one of the three class labels (Positive, Negative and Neutral).

Flair is a natural language processing library (NLP) developed and open-sourced by Zalando Research. Flair's framework is built directly on PyTorch. Comparing with other NLP packages (lexicon based), flair's sentiment classifier is based on a character-level LSTM neural network which takes sequence of letters and words into account to classify the text (corpus based). Flair pretrained sentiment analysis model is trained on IMDB dataset. We have used ‘en-sentiment’ pre-trained model for classification since the data is unlabeled. Unlike the previous rule-based algorithms which return the score in the range − 1 to 1, the classification output for Flair is confidence score in the range 0 to 1 with 1 being highly confident and 0 being unconfident. Flair solely assigns positive or negative polarity to tweets [20].

The workflow of the Sentiment Analysis follows: data acquisition, pre-processing, sentiment extraction and classification. The efficiency of the models was evaluated using metrics such as the macro-F1 score (the harmonic mean of the macro-averaged precision and recall) and classification accuracy. Flair was not considered for model evaluation as the sample tweets were annotated for positive, negative, and neutral labels whereas Flair classifies data as either positive or negative. The data analysis was conducted using Python 3.7.14 [21].

2.3. Coding scheme

The coding team was made of five individuals. Followed by sentiment analysis, each coder was provided with 700 tweets, 600 of which were original and 100 of which were shared with other coders. Coders read their assigned tweets multiple times to familiarise themselves with the data. Based on the stigma communication model, the coders then independently produced a list of issues relating to “mark, group labelling, responsibility, and peril.” The coders then compared the degree of overlap between respective lists. Finally, a codebook was developed in which the four categories of stigma message content act as overarching themes and the individual concerns chosen through the open coding process function as coding variables within these themes. “Misinformation” was added as a variable in the codebook. The tweets were coded in Microsoft Excel. Reporting adheres to Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines (COREQ) [22].

To establish rigour, several strategies were applied, including credibility, transferability, analytic, and trustworthiness. The lead author, in particular, established an audit trail of analysis (i.e., theoretical memos). The credibility of the codes were built through interaction with the lead author in order to gain agreement. All contradictory perspectives were reconciled through reflective practise and systematic consultations with the entire team.

3. Results

A total of 66,387 tweets were passed to sentiment analyser. Table 1 depicts the sentiment categorization using the VADER, Text Blob, and Flair analysers, with the overall percentage of each positive, negative, and neutral tweet identified in the dataset.

Table 1.

Analysis results of VADER, Text Blob and Flair.

| Models | Positive | Negative | Neutral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vader | 34.24% | 45.19% | 20.58% |

| Text Blob | 81.95% | 13.66% | 4.39% |

| Flair | 7.83% | 92.17% | 0.00% |

The tweets extracted were unlabelled and also had a unbalanced class distribution. To evaluate the models used for performing sentiment analysis, we therefore annotated a random sample of approximately 1% of tweets. The accuracy as well as macro-F1 score for the three analysers are given in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Accuracy and macro F1 for VADER, Text Blob and Flair models.

| Models | Accuracy | Macro-F1 |

|---|---|---|

| Vader | 38.54% | 36.00% |

| Text Blob | 35.51% | 28.20% |

| Flair | 40.06% | 22.12% |

In addition, confusion matrices were shown for three classifiers (Fig. 1), to provide additional information regarding which classes were correctly/incorrectly predicted by each classifier. The cells along the antidiagonal line in Fig. 1 represent the proportion of accurately predicted tweets by the classifiers. In Fig. 1, we observe that TextBlob was able to predict accurately most of the positive tweets while in the VADER model the greater spread of incorrect predictions along the diagonal line, showed the “confused” state of the model.

Fig. 1.

Heatmap-confusion matrix.

We randomly selected 3100 tweets from 66,387 tweets and included them in the content analysis if they had at least one type of message content necessary for establishing and disseminating mpox stigma.

3.1. Group labelling

Since the initial outbreak was mainly seen among the queer male community, stigmatization arose, leading to the mislabelling of the Monkeypox disease as the “Gay Man Disease”. Tracing back to the history of epidemiology, similar accusations were seen during HIV/AIDS outbreaks.

There is a massive public outrage from both: ones that support the labelling and a contrasting group that dismisses the allegations against the targeted population. The community and the allies have taken a stand against the gay disease narrative and debunked the misinformation lingering around it. There is a collective effort from their end to raise and spread awareness about the virus and its transmission. Due to the coinciding timelines of the pride parade and the mass outbreak, the queer community fell easy target and being labeled with the disease. The bigotry has accelerated to such surging scales that there have been suggestions to rename the disease into a term that includes gay references. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Tweets related to Group Labelling.

| Group Labelling | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gay disease |

Support “#Monkeypox is Now the way to found out which of your friends are Gay”, “Somebody came to ask me about treatment for monkeypox with t-pox because she had hugged a gay man.’ Debate is raging whether to target mpox vaccination and outreach to men who have sex with men. ‘Stigma is something that we are constantly worried about’” |

Deny “Blaming anyone for the spread of something like monkeypox, especially blaming the gay community or gay behavior, is not sound public health. Viruses, after all, don't discriminate”, “The monkeypox outbreak must not be allowed to fuel racism and discrimination of gay people, a leading infectious disease expert has warned.” “As soon as it was declared a ‘gay disease,’ I knew we would see this. There is too much anguish/suffering, that should not be happening. Once |

| Pride Parade | “Monkeypox outbreak may have been sparked by sex Health chiefs tasked with containing the virus have already begun tracing cases back to the Gran Canarian GAY pride festival – attended by up to 80,000 people between May 5–15.” | |

| Bigotry | “What I understand from the press release is renaming it ‘the gay man disease’ hMPXV should reduce stigma AND transmission?” “I have a new name. Since it is spread in mainly one circle, call it the the ‘Gay Cox Pox’. Be here all night kids.” |

|

3.2. Mark

Marks are pointers or indicators to denote the targeted community. An analysis of the tweets led to certain marks used across the internet: reference diseases and attitudes of denial shown by both the targeted community and the rest of the population. Netizens see mpox as a resemblance to other diseases encountered in the past- HIV/AIDS, COVID-19.

A major challenge surrounding the current outbreak has been spreading awareness without creating stigma. The stigmatization has had a grave impact on both the heterosexual community as well as the LGBTQ+ community. The former community has been affected in a way that they refrain from any public health measures pertaining to mpox, thus, increasing the possibilities of undiagnosed infections. This perspective on the outbreak is well displayed in several tweets, where the part of the population, other than the targeted community, is unaware of the pattern of the transmission, keeping any possible preventive methods at bay. The latter community, already being marginalised, is further alienated because of the false allegations related to the virus outbreak. Social isolation through stigma often imposes a mental-health impact on the targeted community. Solidarity within the male homosexual community and support from allies, are essential and have been well exercised through some tweets. (Table 4).

Table 4.

Tweets related to Mark.

| Mark | ||

|---|---|---|

| HIV/AIDS |

Associating “For those of us who were old enough to witness the horrific hate that was unleashed on the LGBTQ community, and especially gay men, back when HIV/ AIDS hit; it's both disturbing and very frightening to see the same repeated now. We should know better!” “Monkeypox is not AIDS. It is treatable, we have vaccines to prevent it; crucially, unlike HIV infection in the 1980s, the infection does not lead to death in most cases.” |

Dissociating “Monkeypox is not AIDS. It is treatable,we have vaccines to prevent it; crucially, unlike HIV infection in the 1980s, the infection does not lead to death in most cases.” |

| COVID-19 | “Monkeypox is the new COVID, even for those of use who don't do gay orgies, MSM says the vaccines are needed and it's a health emergency. We need mail in ballots in November.” | “The way at the start of COVID 19 pandemic it was blamed on Asian people and now monkeypox is being blamed on lgbt people… im gonna go feral” |

| Stigmatisation |

Targeted Community “As during the #AIDS crisis, gay men cannot wait for the government. We need to change our sexual behavior now. We must do this as an act of empowerment to protect ourselves. Until a time when #monkeypox hopefully abates, this can and should mean.” |

Public “Today I had a conversation with 3 of my coworkers, about monkeypox, and all 3 of them agreed that it wasn't something they were worried about because it's a gay man's disease…”, |

| “The sense among many gay men that WE need to take the initiative to protect both ourselves and public health generally is growing. No one is saying monkeypox is a gay disease. That would be absurd. But what's the risk in closing commercial sex venues?” | “I know homophobes won't take medical situations like this seriously, so it'll be hilarious to see them get monkeypox despite their insistence that it's a gay disease.” | |

| Destigmatisation | “National News Monkeypox Dilemma How To Warn Gay Men About Risk Without Fueling Hate ☝  ” ”“Public health authorities want to warn men who have sex with men that they're at higher risk for exposure. But they fear unintended consequences: heterosexual people assuming they're not susceptible and critics exploiting the infections to sow bigotry.” |

|

3.3. Responsibility

The outbreak of the mpox virus in the present situation has encouraged the public to stay informed and updated. Public health officials have taken the initiative to guide the public to take responsible actions and safety measures. Many tweets arose against the guidelines, especially, discarding mask safety in relevance to the gay disease narrative; mpox has caught the attention of various media houses and the internet. Many reports have been issued regarding the outbreak, and its effects. They have also made a point about the male queer community being highly affected by the current outbreak and how the public has been reacting to the news.

The priority for vaccination is given to the medical professionals, the targeted community, and the vulnerable community. The availability and efficiency of the vaccines has been a debatable topic on the internet.

There have also been tweets spreading awareness about the contact transmission taking place along with airborne potentiality, mostly linked to pride parades, sauna baths and similar places.

Thereby, there have been suggestions to taper the events, closing down places, ensuring safety for public and the targeted community. While there is a population spreading awareness and being responsible, there still is a huge opposition to the measures associated with the virus. (Table 5).

Table 5.

Tweets related to Responsibility.

| Responsibility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Health care measures |

Accepting Stop treating that the monkeypox is a gay disease cause it's not. Treat this like it's covid. Wear mask out in the streets. Social distance. If you have the monkey pox. Stay home! #MonkeyPoxIsAirborne |

Discarding “Now they want you to wear a mask for a disease thats most common form of transmission is unprotected gay male sex. This is the wildest run of midterm shenanigans I've seen yet.” |

| Saying COVID is ‘mild’, we shouldn't mandate masks and Monkeypox is ‘only’ a disease of gay men is wrong, gaslighting and stigmatising to vulnerable disabled and immune compromised people and LGBTIQ ppl - please speak to real experts | They said to wear masks, not sure masks on the face prevents Monkeypox. You'd need to wear it on your ass if you want it to be effective. | |

| Vaccination |

Accepting “Have your say: Will you roll up your sleeve for a Monkeypox shot? User 1: Have your say: Will you roll up your sleeve for a Monkeypox shot?” |

Discarding “Have your say: Will you roll up your sleeve for a Monkeypox shot?’ User 2: No, because I'm not a gay man. Because monkeypox has been an endemic for years and we've potentially been surrounded by it many times. And because I'm not an idiot User 3: I will consult with my doctor to figure out if I'm at risk, and if so, then yes, yes I would get the vaccine.” |

| “Myth: The monkeypox vaccine is widely available” | ||

| Awareness |

Spreading awareness “usually spreads through close contact with someone with rashes or lesions, which includes sex but can also include hugging, skin-to-skin contact while dancing or sharing contaminated clothing & bedding, or through droplets over a prolonged period” |

Negligence “Just like Climate Change......I'm ignoring Monkeypox.” |

| Media Fear Mongering | “The media trying to imply that monkeypox is an STD favouring gay men is fear mongering and we have seen this before” | |

3.4. Peril

Peril refers to the threat and danger posed by the targeted community to the public or society. Fearing the spread of the disease from the targeted community, there has been violence reported across the world. There have been physical and verbal attacks on couples found in public causing harm to their day-to-day lives, leading to panic and stigmatisation.

People have discarded basic preventive measures by claiming that the disease only affects the queer community and that the fear-mongering surrounding it is invalid or not applicable to them.

Claims linking political reasons and fear-mongering are observed. Criticising the government for insufficient measures taken, different sections of the population are holding each other responsible for the unexpected outbreak of mpox. (Table 6).

Table 6.

Tweets related to Peril.

| Peril | ||

|---|---|---|

| Attacks |

Physical attacks “A gay couple were reportedly assaulted by a group of teenagers.” |

Verbal attacks “Gay couple called “monkeypox f****ts” during homophobic attack |

| Panic | “No. because the gay panic stigma with monkeypox, they are being stigmatized by something folks don't choose” | |

| Politics | “Lol..I'm waiting for how they will tie the risk of gay sex in the voting lines and needing mail in ballots to ensure monkeypox doesn't spread and interfere with the rights of people to vote… getting popcorn  ready! Lol” ready! Lol” |

|

| “Because the government keeps with the lie that monkeypox is a gay illness they are putting everyone at risk for an illness that can disfigure and blind you if left untreated. The government is harming so many with their lies.” | ||

3.5. Misinformation

As the first health advisory circular was released by WHO, it included specific guidelines for vulnerable communities: pregnant women, children, HIV/AIDS-infected individuals, and the male homosexual community. However, there was a high level of misinterpretation, leading to several false beliefs. Both the health officials and the public are cautious to use the right terminologies to avoid further misinterpretation. Amidst a sea of misinformation spreading in terms of stigmatisation or blaming the government, another wave now emerging is regarding various conspiracy theories proposed by users across the globe. However, well-informed users are trying to debunk misinformation. (Table 7).

Table 7.

Tweets related to misinformation.

| Misinformation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Misinterpretation |

Spreading misinformation “Many people are going to suffer and die because our capitalist media and government decided to pretend monkeypox can only happen to gay men.” |

Against Misinformation “Can we pls report that tweet linking monkeypox to gay men for misinformation? |

| Another problem for public health communication, is if people think it's a “gay thing”. Monkeypox is not an STI. It's spread by close contact, which doesn't have to be sexual in nature. There's a risk that people will erroneously conclude it can only affect men or gay men. | ||

| Conspiracy |

Conspiracy theories It's probably the vaccine causing the monkeypox you inept loser. |

Against the theories “We must hold people who spread disinformation!!! We don't need any more man-made chaos, while mother nature keeps unleashing her angers!” |

| The (AZ) AstraZeneca vaccine contains a dose of chimpanzee bits and bobs. I'm no doctor but...... #monkeypox | When you imagine there's a powerful group behind everything, that's a symptom of schizophrenia. Covid and Monkeypox are diseases. They are spread by the usual suspects: immigrants, LGBT, etc. There is no grand conspiracy behind it. |

|

4. Discussion

The mpox cases are escalating at global level and the stigma and discrimination related to it remains unabated and the LGBTQ+ group continue to grapple with the intended and unintended consequences, with a special focus on the gay community. Social media platforms are increasingly being used by health professionals to combat infodemics, and they have been adopted during COVID-19, ebola, and other outbreaks. Utilizing the social media platform the health system can track the dissemination of unregulated media, misinformation related to this event [23,24]. Using the “model of stigma communication” this paper has foregrounded how the process of stigmatization is evolved [13]. The following paragraphs emphasise how healthcare organisations have taken both immediate and long-term actions to respond to the current mpox outbreak, as well as how the transmission of scientific information has been influenced by the elements described in the subsequent models “Multipronged approach to deal with the infodemic” and the “A nested model of policy capacity” [25,26].

The “Model of Stigma Communication” explains how stigma communicates. It focuses on how cognitive processes originate stigmatisation, how stigmatised groups react to it, and, finally, the effect of exchanging messages. This study's findings support this paradigm of the stigmatisation process [13]. As the pattern of mpox surge is demonstrating a ripple effect among the LGBTQ+ communities, it has led to an imprint mark among the community as the spreader. Similar to this study and as emphasized by this model, stigma associated with HIV infection is still well recognised as a disease that occurs between MSM and within communities of LGBTQ+ community [27]. The dissemination of incorrect facts led the public to infer that the outbreak was caused by the LGBTQ+ community and that it was labelled as a “gay disease” [28]. A few studies also highlights the consequences of dissemination of incorrect facts during COVID-19 [29]. As a result of the initial outbreak largely impacting the LGBTQ+ community, which caused the mpox disease to be mislabelled as the “LGBTQ+ community man disease”, issues of homophobia and stigmatisation arose. When HIV/AIDS outbreak occurred, similar accusations have been made in the past [30]. Thus the message of choice for stigmatization, the term “LGBTQ+ community disease”, violence among the community, group labelling among the LGBT+ community became a message of choice for stigmatization. These kind of stigmatization is also seen highlighted in a study on HIV AIDS [31].

Stigmatization began to flare up when the LGBTQ+ community and groups, were identified as the outbreak's primary mass-spreaders. As a result, the community became a distinct social group. This process puts the community in peril on both a physical and social level, ultimately implicating the “homosexual community”. This cycle of stigmatisation has already been demonstrated, and the findings of this study are similar to those of earlier studies [13]. They are vulnerable due to their experiences with being stigmatised, being classified as a distinct entity, discrimination, a lack of social justice, or inadequate services. These had a knock-on impact the development of stigma attitudes by encouraging stereotypes, inducing affective responses (disgust, wrath, and fear), and fostering associated action inclinations. Misinformation was widely disseminated as a result of this stigmatisation.

Fig. 2 demonstrates the adaptation of model of stigma communication [13]. According to this model, stigmatisation is a two-way process. Where the message choices made by the public have unintended consequences for vulnerable community groups. These reactions include stigmatisation as a “gay man disease,” violence against the LGBTQ+ community, prejudice, and group labelling. These reactions' effects on the targeted group have an adverse effect on them directly. There have been numerous reports of severe unhealthy incidents as the stigmatisation process spreads quickly among these populations. The negative comments expressed by both the public and the targeted community are exacerbated by these reasons. The stigmatisation of the LGBTQ+ community spreads as a result of these consequences which creates an impact on the non-stigmatized, creating dispersion of stigmatization among the general population. This study demonstrated that, despite the public's lack of understanding of mpox and its transmission routes, the LGBTQ+ community had been placed in the position of feeling responsible and posing a threat to the public health system.

Fig. 2.

Adaptation of model of stigma communication [13].

The “Multipronged approach to deal with the infodemics” highlights three approaches based on time period [26]. It comprises pre-emptive measures, Immediate measures and the long-term measures. These three measures explain the steps that can be adopted to strengthen a health system during a health emergency. As per the model, the pre-emptive measures navigate the people to curb the health condition in a pre-emptive way. This study reveals how the role of various health agencies came up to clear the misinformation about mpox among the public. As there were a high level of misinterpretation, leading to the false belief that mpox is a sexually transmitted disease. A similar study also argued the same [32]. There was also a notion that the disease was only limited to the targeted population. To demystify these, health advisory circular was released by WHO, it included specific ways to work to accelerate and fund priority research that can contribute to curtail this outbreak and prepare for future outbreaks for vulnerable communities [33]. However, these agencies roles are found not very evident to curb the misinformation, defining the exact route of transmission during this ongoing mpox outbreak. For the immediate measures, the health systems particularly the WHO and CDC have issued their guidelines taking an interest in the well-being of the vulnerable population as well as the public. The WHO's Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan was created in February 2020 to halt the spread of the COVID-19 virus, save lives, and safeguard the weak [34]. The population believes that mpox is a disease that affects LGBTQ+ communities and is not a concern for the broader population, hence the response to mpox is not perceived as being particularly panicked [35]. As an immediate measure to curb the escalating numbers, the WHO and CDC have issued their guidelines taking an interest in the well-being of the vulnerable population as well as the general public [36]. Numerous debates have been sparked by the widespread distribution of mpox among the general public, and numerous healthcare organisations have been formed to fill the gap. Due to negative social attitudes and preconceptions, with the US and Spain being the key destinations, the LGBTQ+ community is frequently demonised as being responsible for the transmission. Added to this prejudice based on race, class, and religion also found during this ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the derogatory nomenclatures such as ‘Chinese-virus’ or ‘Corona-jihad’ could be seen as a part of a disjunctive politics of ‘representation’ as opposed to ‘representing’ with a metonymic effect [37]. Similar to our findings, a model also illustrates the process progression of stigmatisation. The population acquired unfavourable cognitive attitudes against the vulnerable community as a result of the negative mass dissemination of misinformation, which resulted in increased violence, harassment, and isolation.

This research has limitation. The sample size for content analysis was minimal in comparison to the total amount of tweets provided. In the current study, we focused on Twitter since it is increasingly utilised by researchers to analyse public reaction to epidemics. More research is required to completely comprehend public perspective.

5. Conclusion

The mpox infodemic has grown to immense proportions. As a result, the CDC and WHO have taken an immediate action to prevent or contain the infodemic. The nested model of policy capacity highlights that the nature of the challenges government's face in performing policy functions and its competencies [25]. At the analytical level, the WHO and the CDC appear to be lacking in their efforts to combat mpox by employing technical and scientific knowledge and analytical methodologies. Similarly, organisational operational capacity reveals a failure to undertake crucial administrative duties in reducing stigmatisation.

The impacts of stigmatisation have jeopardised the mental health of the targeted community. People who are stigmatised and discriminated against have their human rights violated continuously, and they may suffer from serious mental illness. They may face inhumane living circumstances, physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and brutal and demeaning treatment procedures in medical facilities. They frequently lack the civil and political rights required to fully participate in public life and to use their legal authority to address other issues affecting them, such as their treatment and care. People frequently live in vulnerable conditions, and as a result, they may be excluded from and marginalised by society, severely impeding the achievement of national and global development goals. At the individual level, to bridge these gaps and strengthen mental health status alongside physical health, concerned health authorities should implement the necessary action plan to address mental health and well-being; this is stressed in the comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030. It is an issue that can be supported at the individual-political capability level. There is a need for a system to track the dissemination of unregulated media, particularly social media. Each nation needs to strengthen its health system and create risk communication strategies that fill in the gaps in order to prevent stigmatised diseases like mpox without blaming the affected.

Role of funding source

There was no funding source for this study. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Prasanna School of Public Health (PSPH), MAHE staff for providing the logistical support.

References

- 1.Alakunle E., Moens U., Nchinda G., Okeke M.I. Monkeypox virus in Nigeria: infection biology, epidemiology, and evolution. Viruses. 2020;12(11) doi: 10.3390/V12111257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornhill J.P., Barkati S., Walmsley S., et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 Countries — April–June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(8):679–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2207323/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMOA2207323_DATA-SHARING.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-07-2022-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-(ihr)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi-country-outbreak-of-monkeypox Accessed September 9, 2022.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2022 Monkeypox Outbreak Global Map. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html Accessed September 9, 2022.

- 5.Pan American Health Organization Epidemiological Update Monkeypox in children, adolescents, and pregnant women. August 4, 2022. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/epidemiological-update-monkeypox-children-adolescents-and-pregnant-women-4-august-2022 Accessed September 15, 2022.

- 6.Tusabe F., Tahir I.M., Akpa C.I., et al. Lessons learned from the ebola virus disease and COVID-19 Preparedness to respond to the human monkeypox virus outbreak in low- and middle-income countries. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:6279–6286. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S384348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilder-Smith A., Osman S. Public health emergencies of international concern: a historic overview. J Travel Med. 2020;27(8):19. doi: 10.1093/JTM/TAAA227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinnenberg L., Buttenheim A.M., Padrez K., Mancheno C., Ungar L., Merchant R.M. Twitter as a tool for health research: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boon-Itt S., Skunkan Y. Public Perception of the COVID-19 pandemic on twitter: sentiment analysis and topic modeling study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(4) doi: 10.2196/21978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rueda S., Mitra S., Chen S., et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7) doi: 10.1136/BMJOPEN-2016-011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preston D.B., D’Augelli A.R., Kassab C.D., Starks M.T. The relationship of stigma to the sexual risk behavior of rural men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(3):218–230. doi: 10.1521/AEAP.2007.19.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhanot D., Singh T., Verma S.K., Sharad S. Stigma and discrimination during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;8:829. doi: 10.3389/FPUBH.2020.577018/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith R.A. Language of the lost: an explication of stigma communication. Commun Theory. 2007;17(4):462–485. doi: 10.1111/J.1468-2885.2007.00307.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twitter Twitter API for academic research | twitter developer platform. 2022. https://developer.twitter.com/en/products/twitter-api/academic-research Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 15.Loria S. Textblob documentation. 2018. https://textblob.readthedocs.io/en/dev/ Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 16.Hutto C.J., Gilbert E. VADER: a parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. Proc Int AAAI Conf Web Social Media. 2014;8(1):216–225. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14550 Accessed September 21, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twitter Developer Platform Developer agreement and policy – twitter developers. 2022. https://developer.twitter.com/en/developer-terms/agreement-and-policy Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 18.Taboada M., Brooke J., Tofiloski M., Voll K., Stede M. Lexicon-based methods for sentiment analysis. Comput Linguist. 2011;37(2):267–307. doi: 10.1162/COLI_A_00049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turney P.D. December 11, 2002. Thumbs up or thumbs down? Semantic orientation applied to unsupervised classification of reviews. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbik A., Bergmann T., Blythe D., Rasul K., Schweter S., Vollgraf R. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North. 2019. FLAIR: an easy-to-use framework for state-of-the-Art NLP; pp. 54–59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.python Python 3.7.14. September 6, 2022. https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3714/ Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 22.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/INTQHC/MZM042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury N., Khalid A., Turin T.C. Understanding misinformation infodemic during public health emergencies due to large-scale disease outbreaks: a rapid review. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2021 doi: 10.1007/S10389-021-01565-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bin Naeem S., Bhatti R. The Covid-19 “infodemic”: a new front for information professionals. Health Info Libr J. 2020;37(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/HIR.12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu X., Ramesh M., Howlett M. Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. 2017;34(3–4):165–171. doi: 10.1016/J.POLSOC.2015.09.001. New pub: Oxford University Press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dash S., Parray A.A., de Freitas L., et al. Combating the COVID-19 infodemic: a three-level approach for low and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(1):4671. doi: 10.1136/BMJGH-2020-004671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smit P.J., Brady M., Carter M., et al. HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: a literature review. AIDS Care. 2012;24(4):405–412. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.613910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.März J.W., Holm S., Biller-Andorno N. Monkeypox, stigma and public health. Lancet Reg Health - Europe. 2022;23 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):510. doi: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logie C.H., Lacombe-Duncan A., Brien N., et al. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing among young men who have sex with men and transgender women in Kingston, Jamaica: a qualitative study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kontomanolis E.N., Michalopoulos S., Gkasdaris G., Fasoulakis Z. The social stigma of HIV–AIDS: society’s role. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2017;9:111. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S129992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brainard J., Hunter P.R. Misinformation making a disease outbreak worse: outcomes compared for influenza, monkeypox, and norovirus. Simulation. 2020;96(4):365. doi: 10.1177/0037549719885021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) Global research and innovation forum. February 12, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum Accessed September 16, 2022.

- 34.World Health Organization Looking back at a year that changed the world: WHO’s response to COVID-19. February 24, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/looking-back-at-a-year-that-changed-the-world-who-s-response-to-covid-19 Accessed September 16, 2022.

- 35.Nina P.B., Dash A.P. Hydroxychloroquine as prophylaxis or treatment for COVID-19: What does the evidence say? Indian J Public Health. 2020;64(6):125. doi: 10.4103/IJPH.IJPH_496_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization Recovering from monkeypox at home. July 24, 2022. https://www.who.int/multi-media/details/recovering-from-monkeypox-at-home?gclid=Cj0KCQjwpeaYBhDXARIsAEzItbGFNcWoEABpJHTR5GapXoAkeQ8FYFh3wokkZtHEGoYc_V9QZnOfYngaAoVJEALw_wcB Accessed September 16, 2022.

- 37.Biswas D., Chatterjee S., Sultana P. Stigma and fear during COVID-19: essentializing religion in an Indian context. Human Social Sci Commun. 2021;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00808-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]