Dear Editor,

The COVID-19 pandemic was undoubtedly the most critical event that the Italian National Health Service (NHS) had to face in its history. To cope with the emergency, the Italian NHS had to stop most elective care, at least during the first phase of the outbreak. However, such state of crisis had also a positive side: it accelerated the spread of telemedicine, particularly for cancer and chronic patients. The recent WHO Global Safety Action Plan highlights the importance to develop and implement digital solutions, such as telemedicine to improve quality and safety of care [1].

The EU has taken major initiatives to strengthen public health sectors in member states and mitigate the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic. One of the first actions was Next Generation EU (NGEU), through which €750 billion were allocated to stimulate growth, investment, and reform [2]. Much of this funding is targeted at the health sector for digitization and deployment of telemedicine systems in healthcare. For Italy in particular, resources of up to 20 billion euros are planned for these purposes.

Today, the market offers a variety of applications for telemedicine services. The main applications are tele-visit, tele-assistance, tele-monitoring, and teleconsultation [3]. Their success is often due to the ability of healthcare operators to implement them in operational contexts with different technological quality and various levels of personnel training about the digitization [4].

In view of these large investments, we decided to take a snapshot of telemedicine diffusion at the national level to define a baseline and identify actions to be taken for the real development of a new model of digital healthcare in Italy.

From February 1 to March 31, 2022, information regarding the use of telemedicine was collected by an anonymous questionnaire disseminated to Italian healthcare operators through the risk management network. Data were collected by snowball sampling. In fact, the questionnaire was disseminated through different channels: either through the company website or by sending e-mails to all staff.

Participating providers were asked to answer to 6 questions:

Do you use Telemedicine in your professional activities?

Which telemedicine application do you use?

Have you received specific training on Telemedicine services?

What equipment has been provided to you?

In your experience, do you feel that Telemedicine is useful to improve your work?

In your experience, do you think that patients feel cared for and protected when they are assisted through telemedicine?

731 healthcare workers responded to the questionnaire, from which 4 were excluded because they were not complete. The respondents were mainly women (72%), aged 35–55 years (51%); 45% of them were nurses, 25% physicians, 9% researchers/students, 6% social and health care workers, 6% technicians; 29% worked in medical wards, 26% in emergency, 13% in the surgical department and 32% in other areas (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents

| Characteristics | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 202 | 28 |

| Female | 525 | 72 |

| Age range | ||

| < 35 | 177 | 24 |

| 35–55 | 368 | 51 |

| > 55 | 182 | 25 |

| Work placement | ||

| Hospital agency | 269 | 37 |

| University Hospital | 313 | 43 |

| Local health authority | 122 | 17 |

| Territorial services | 23 | 3 |

| Professional role | ||

| Physician | 182 | 25 |

| Nurse | 330 | 45 |

| Operator social health | 47 | 6 |

| Technician | 42 | 6 |

| Researcher/student | 66 | 9 |

| Other | 60 | 8 |

| Clinical area of reference | ||

| Emergency-urgency | 188 | 26 |

| Medical | 213 | 29 |

| Surgical | 92 | 13 |

| Other (radiologi, clinical patology ecc… emergency, medical sargia | 234 | 32 |

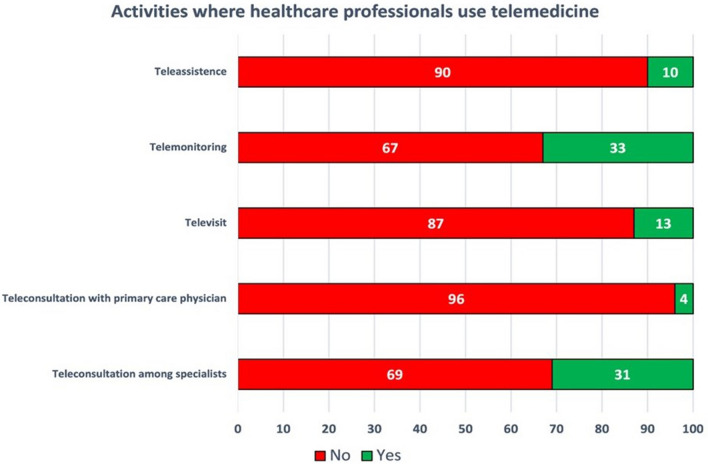

Collected data show that only 13% of respondents (100 healthcare workers) already use telemedicine systems (in its broadest sense). A binary logit model has been implemented to observe the factors that play a role in determining the likelihood of using telemedicine. Results show that females are less inclined to use telemedicine than males; healthcare professionals working in university hospitals and local health companies have a higher propensity to use telemedicine compared with healthcare workers enrolled in non-academic hospitals; finally, nurses and social health operators are less likely to employ telemedicine than doctors. Telemedicine is mainly used for consultation among specialists. On the contrary, teleconsultation results scarcely used with general practitioners. Tele-visit is limitedly used, as is tele-assistance, while tele-monitoring of patients seems to be quite widely used for remote management of patients. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Activities where healthcare professionals use telemedicine: for each activity, it is reported the percentage of respondents (healthcare professionals) who declared to employ (green bars) or not to employ (red bars) telemedicine in that activity

Only 18% of users of digital systems have received specific training, and the most commonly used tool is their own PC. No platforms developed specifically for telemedicine services have been reported by respondents.

The survey, however, shows that 85% of respondents consider useful to implement telemedicine systems for patient management. Only 3% of them say that users do not feel protected as patients from remote management, most (68%) declare that patients, cared by telemedicine, feel protected. The answers given on its real usefulness still show a lack of conviction: only 25% are very convinced of its usefulness, while 60% are only “fairly” convinced. This is perhaps due to the limited training of healthcare professionals. An important strategy for their diffusion would be to promote training initiatives that demonstrate the benefits, but also the correct conditions for implementing the technology before introducing it in various operational contexts [4].

Data demonstrate a still very limited use of telemedicine in Italy, despite the pandemic input. Although its use has tripled since the pandemic, Italy is still far behind other countries where COVID has made a strong push. According to 2021 statistics, telemedicine is used for 13–17% of U.S. patient visits in all specialties. The number of telemedicine visits increased by 50% in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the first quarter of 2019, stabilizing at a level 38 times higher than before the pandemic [5].

Although our study has limitations related to the representativeness of the sample and the fact that the collection of responses was snowballing, it is in line with the results of other studies conducted nationwide.

The data show that telemedicine is little and not uniformly widespread in Italy—most of the responses are from health care providers in regions with advanced health care systems—and that there has been little adoption of these methodologies in hospital settings. In addition, the use of structured Telemedicine services is still marginal, and one of the most critical issues is the lack of adequate digital skills of healthcare professionals.

We are currently unable to assess how widespread these methodologies are in the primary care setting, but we believe that since there has been no specific funding for tele-monitoring or tele-visiting, it is reasonable to assume that they are in a less advanced state than the hospital setting.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Human and animal rights statement

The study was submitted to the ethics committee of Guglielmo Marconi University and was exempted from full review as only anonymous administrative data was evaluated.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informedconsent priorto the partecipation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2021) Global patient safety action plan 2021–2030: towards eliminating avoidable harm in health care. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/policy/global-patient-safety-action-plan. Last accessed August 3, 2021.

- 2.European Commission. Recovery plan for Europe. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en#nextgenerationeu. Last accessed Jun 16, 2021

- 3.Tuckson RV, Edmunds M, Hodgkins ML. Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1503323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parretti C, Tartaglia R, La Regina M, Venneri F, Sbrana G, Mandò M, Barach P. Improved FMEA methods for proactive health care risk assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of COVID-19 remote patient telemonitoring. Am J Med Qual. 2022 doi: 10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarazi W, Ruhter J, Bosworth A, Sheingold S, and De Lew N (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medicare FFS beneficiary utilization and provider payments: FFS data for 2020 (Issue Brief No. HP2021–13). Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.