Abstract

Background

The main protease is an important structural protein of SARS-CoV-2, essential for its survivability inside a human host. Considering current vaccines' limitations and the absence of approved therapeutic targets, Mpro may be regarded as the potential candidate drug target. Novel fungal phytocompound Astrakurkurone may be studied as the potential Mpro inhibitor, considering its medicinal properties reported elsewhere.

Methods

In silico molecular docking was performed with Astrakurkurone and its twenty pharmacophore-based analogues against the native Mpro protein. A hypothetical Mpro was also constructed with seven mutations and targeted by Astrakurkurone and its analogues. Furthermore, multiple parameters such as statistical analysis (Principal Component Analysis), pharmacophore alignment, and drug likeness evaluation were performed to understand the mechanism of protein-ligand molecular interaction. Finally, molecular dynamic simulation was done for the top-ranking ligands to validate the result.

Result

We identified twenty Astrakurkurone analogues through pharmacophore screening methodology. Among these twenty compounds, two analogues namely, ZINC89341287 and ZINC12128321 showed the highest inhibitory potentials against native and our hypothetical mutant Mpro, respectively (−7.7 and −7.3 kcal mol−1) when compared with the control drug Telaprevir (−5.9 and −6.0 kcal mol−1). Finally, we observed that functional groups of ligands namely two aromatic and one acceptor groups were responsible for the residual interaction with the target proteins. The molecular dynamic simulation further revealed that these compounds could make a stable complex with their respective protein targets in the near-native physiological condition.

Conclusion

To conclude, Astrakurkurone analogues ZINC89341287 and ZINC12128321 can be potential therapeutic agents against the highly infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Keywords: COVID 19, Principal component analysis, MD Simulation, ZINC compounds, Phytochemicals

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The novel Severe Acute Respiratory Corona Virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), an etiological agent of COVID-19 caused the first pandemic of the 21st century and has brought the world to a halt. On 11th March 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic as the cases were reported from different parts of Asia and Europe [1,2]. Till July 2022, the world witnessed 632,953,782 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6,593,715 deaths (https://www.who.int/). The asymptomatic patients might likely contribute to the development of this pandemic; therefore, the actual number of infected cases probably is much higher than reported. Coronavirus was known to cause two global outbreaks related to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV in 2002 [3,4] and 2012 [3,5], respectively. However, in terms of the transmissibility rate [3] and the number of deaths [6], the novel SARS-CoV-2 alarmingly exceeded both SARS and MERS outbreaks. The mortality rate of SARS and MERS was reported to be 3 (https://www.who.int/health-topics/#S) and 35%, respectively (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets), while the case fatality rate of SARS-CoV-2 was 1.04% (6,593,715 deaths out of 632,953,782 reported cases as of November 2022) (https://covid19.who.int/) only. The signs and symptoms related to the disease include high fever, chills, cough, shortness of breath or difficulty in breathing, diarrhoea, myalgia or fatigue, expectoration, and haemoptysis with an incubation period of 2–7 days [7].

Since the outbreak, numerous repurposed therapeutic agents have been reported against SARS-CoV-2 [8]. An antiviral drug like remdesivir [9] had been clinically tested against the virus, but the efficacy result was uncertain [10]. Other antiviral drugs such as lopinavir and ritonavir showed their potential to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [11]; however, these compounds had no benefit in adult patients against severe COVID-19 infection [12]. Telaprevir, an FDA approved anti-HCV drug, also showed great efficacy as a potent protease inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 in multiple studies (Mahmoud et al., 2021) [13,14]. The combination of an anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine and a macrolide antibiotic azithromycin was reported to be comparatively effective for treating COVID-19 [15]. Hydroxychloroquine, facilitates endosomal acidification and inhibits glycosylation of the host cell receptors and thereby blocking viral entry [16]. Recently, another protease inhibitor paxlovid, was granted emergency authorization by FDA for the treatment of COVID-19 infection, since it showed positive results in the phase 2/3 Evaluation of high-risk patient group [17]. Nevertheless, being a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 system CYP3A enzymes, paxlovid may pose serious harm to the patient [18]. All these synthetic agents are well known for their deleterious side effects, including diarrhoea, headache, and neutropenia [19,20].

SARS-CoV-2 or Coronavirus is a non-segmented positive sense single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus belonging to the genus betacoronavirus and family coronaviridae [7,21]. The genome of the virus is packaged within the nucleocapsid, surrounded by a membrane that is made up of membrane protein, envelope protein and spike glycoprotein. Coronavirus initiates the infection through spike protein attaches to the host cellular receptor [21,22]. In general, most studies targeted spike protein for identifying potent antiviral drugs [[23], [24], [25]], including our previous work [26]). Nevertheless, besides spike protein, the enzyme main protease (Mpro) plays an essential role in successful viral penetration to the host cell, replication and maturation of viral particles [27,28]. It is a 33.8 kDa protein encoded by a frameshift between two open reading frames (Orfs), Orf1a and Orf1b, of the 5’ end cap region of the positive-stranded RNA genome [21,27]). Mpro, along with papain-like protease, cleaves the polyprotein PP1a and PP1ab into 16 non-structural proteins responsible for viral replication and maturation [22,[27], [28], [29]]. Therefore, the main protease of coronavirus can be considered a prospective drug target [30].

Natural compounds have been long tested for their efficacy against a range of aliments and are generally regarded as safe and effective alternatives to synthetic ones. Given the ever-rising complexity of various diseases, the scientific focus is more driven toward compounds of botanical origin. Recent studies also indicated a similar trend towards COVID-19 research [[31], [32], [33], [34]]. In our previous studies, we tested various phytochemicals including curcumin as the antiviral agents against SARS-CoV-2 [[35], [36], [37]] studied the effect of isolated phytochemicals from Helichrysum bracteatum against the viral protein Mpro. In a similar study, Ristovski et al. (2022) [38] showed biflavonoids and tannins as the major class of compounds optimally targeting Mpro. Limited but a few other reports are also available on the use of phytochemicals, explicitly targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [34,39,40].

For screening of drug candidates, computer-aided drug discovery offers a considerable advantage over the conventional one in terms of turnover period, funding and efficiency. CADD tools such as molecular docking and pharmacophore-based modelling effectively aid in finding effective therapeutics against a specific protein by targeting ligand-protein interaction at the molecular level [[41], [42], [43]]. Recent therapeutic hunt for treating COVID-19, witnessed a major application of such technique for the preliminary investigation of drug candidates. In our previous study, we reported curcumin as the major therapeutic agent of botanical origin against SARS-CoV-2 [35]. Asadirad et al. (2022) [44] reported a positive outcome of curcumin when treated for mild‐to‐moderate hospitalized COVID‐19 patients, thereby validating the importance of in silico tools.

Astrakurkurone, a novel triterpenoid, was isolated from the wild edible mushroom Astraeus hygrometricus [45]). Several scientific evidences from our group, showed several biological functions of Astrakurkurone, such as antimicrobial and antiparasitic activities [46,47]. Apart from that, Astrakurkurone was found to be especially efficacious against cancer cells. A study by Dasgupta et al. (2019) [48] demonstrated that Astrakurkurone is cytotoxic towards liver cancer cells, and it induces apoptosis. According to the prediction, the induction of apoptosis was brought about by the molecular interaction between Astrakurkurone and anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl 2 and Bcl-xL at an intracellular level. In this backdrop, we evaluated the potential role of Astrakurkurone in inhibiting Mpro of SARS-CoV-2, in silico. A series of bioinformatics tools, namely, drug likeness analysis, molecular docking, pharmacophore based analogue modelling and multivariate statistics were employed to study the functional role of Astrakurkurone against the target protein. Furthermore, seven mutations were introduced into the native Mpro and inhibitory potential of Astrakurkurone and its analogues were studied.

2. Experimental

2.1. Pharmacophore-based modelling of Astrakurkurone analogues compounds

Pharmacophores are the functional groups, namely hydrogen bond (H-bond), ionic charges, lipophilic-aromatic contact and hydrophobic groups, responsible for effective protein-ligand interaction. Hence, pharmacophore-based modelling relies on selecting these chemical groups to design new drug candidates to confirm the optimum protein-ligand interaction. In this study, we used pharmacophore approach to generate multiple analogues from the parent compound i.e. Astrakurkurone. A three-dimensional interaction model from the Astrakurkurone-Mpro docked complex was generated and three major pharmacophores were submitted to the ZINCPharmer (http://zincpharmer.csb.pitt.edu/pharmer.html) database for pharmacophore analogue generation. ZINCPharmer is an open-access pharmacophore modelling server and a subset of the parent ZINC database, which contains 22,724,825 purchasable compounds [49]). Based on the RMSD values top 20 analogues of Astrakurkurone were selected for this study.

2.2. Preparation of ligand

Prior to the molecular docking experiment this step was performed to optimize the structure of ligands in a three-dimensional space. Initially, a three-dimensional structure of Astrakurkurone (139587813) was downloaded from the PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) database. Avogadro chemical editing software was used for protonation and geometric optimization of the ligand. Furthermore, energy minimization was performed by the force field MMFF94 [[50], [51], [52], [53], [54]], with the parameters 5000 steps, steepest descent algorithm and 10−7 convergence [55]. Telaprevir was reported as one of the major inhibitory drugs for the target SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [56]. It inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro with IC50 at 11.552 μM [57]. Considering this evidence, Telaprevir was selected as the control drug for our study. The three-dimensional structure of the molecule was downloaded from the DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/) and optimized as mentioned earlier. All analogues of Astrakurkurone were also optimized in Avogadro.

2.3. Preparation of receptor protein

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) (PDB ID-6LU7, X-ray Diffraction at 2.16 Å) was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). The protein structure was optimized by using AutoDock tool 1.5.7 and Swiss-PdbViewer v4.1 software. All heteroatoms, water molecules and non-polar Hydrogen were removed from the protein and polar Hydrogen was added maintaining physiological pH. Finally, energy minimization was performed for the final preparation of the receptor before docking. Furthermore, seven mutations (GLY15SER, THR24ALA, MET49THR, GLY71SER, LEU89PHE, LYS90ARG, and PRO108SER) were introduced by using PyMol 2.5 into the optimized native protein and the mutant Mpro was formed [58]. These mutations were introduced based on the data reported on the variants of the Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 [59].

2.4. Effect of mutations on the Mutant Mpro

Structural stability of an enzyme is of high importance as it translates into its catalytic function in the physiological environment [60]. Therefore, the effect of seven introduced mutations on Mpro stability was evaluated by the Site Directed Mutator 2 (SDM 2) server (http://marid.bioc.cam.ac.uk/sdm2). SDM 2 is an open-source knowledge-based web-server to predict the effect of mutations in conformationally constrained environment-dependent amino acid substitutions. Parameters, namely Occluded Surface Packing value (OSP), Residual depth, Residue relative to solvent accessibility (RSA %), and Predicted stability change (ΔΔG) were used to express the result for both wild and mutant type proteins. OSP is the function of Occluded surface area, the average normal unit distance between non-bonded atom molecular surface and neighbouring Van Der Waals surface based on the 2.8 Å surrounding molecular surface of non-bonded atoms. Residual depth represents the average distance between atom depths and the nearest water molecule surface for a given molecule. The free energy difference between wild-type and mutant type residues is represented by ΔΔG [61]. Earlier studies showed that ΔΔG interacted well with packing parameters such as OSP and residual depth [62] to explain the thermodynamics of the protein.

2.5. Active site prediction, molecular docking, heat map generation and interaction analysis

Molecular docking is an important computer aided drug discovery tool to understand and evaluate the molecular interactions between small molecules and target proteins [63]. Various studies successfully employed this tool to analyse the inhibition potential of candidate drugs against target enzymes [33,64]. In this study, molecular docking of 22 compounds, including the control drug Telaprevir and Astrakurkurone with the SARS-CoV-2 protein Main Protease (Mpro), was performed by using AutoDock Vina 1.1.2 software. AutoDock Vina is considered a highly accurate docking program that relies on the high-quality screening benchmark provided by the Watowich group [65]. This program is capable of performing near native docking and is frequently reported to have superior performance compared to other docking software [66].

Discovery Studio 2020 (BIO-VIA, San Diego, USA) was used to determine the active site of the proteins (Native and Mutant). The grid for the AutoDock was set as per the center (X = −10.729204, Y = 12.417653 X z = 68.816122) and size (x = 11.85, y = 11.85 and z = 23.34) values. Molecular protein-ligand interactions were visualized by Maestro 13.3 (Schrodinger, Germany) and Discovery Studio 2020. Docking results were expressed as binding affinity (Kcal mol−1). Finally, two coloured heat map was generated by using TBtools software to express binding affinity (Kcal mol−1) values.

2.6. Evaluation of drug-likeness

The SwissADME server (http://www.swissadme.ch/) was used to evaluate the drug-likeness of twenty-two (22) selected compounds, including the control drug Telaprevir, using canonical SMILES of the structures. SwissADME computes multiple parameters such as pharmacokinetics, biophysical and medicinal chemistry to assess the drug-like properties of the submitted compounds. A few selected parameters namely topological polar surface area (TPSA), gastrointestinal absorption, PGP substrate, lipophilicity (XLOGP3), water solubility (Log S) and the five rules of Lipinski were considered as the evaluation matrices for this study.

2.7. Principle Component Analysis (PCA)

The Principal Component analysis is a statistical tool that reduces the complexity of larger data sets and improves the interpretation without compromising data. PCA provides multiple components or clusters which are orthogonal to each other. Among the projected Principal components, PC1 represents the maximum variance of the dataset [67,68]. Minitab software was used to perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA), to statistically cluster phytocompounds based on their binding affinities as described in our earlier study [36]. Briefly, molecular docking affinity data (Kcal mol−1) was used as inputs for the analysis. Based on component loading and proximity parameters, clusters were identified.

2.8. Structural alignment and pharmacophore study

Pharmacophores of molecules represent the functional groups of the ligands, which are responsible for the biological activity of the candidate drugs. The pharmacophore model is an ensemble of steric and electronic groups, ensuring optimal molecular interactions related to specific functions [69]. The top two clusters were selected for structural alignment based on the PCA output. PharmaGist webserver (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PharmaGist/) [70,71] was used to perform molecular alignment and identification of the common pharmacophores of the selected groups. PharmaGist is an online server which predicts the pharmacophore and molecular alignment based on four principles: ‘ligand representation, pairwise alignment, multiple alignments and solution clustering and output’. The alignment score is generated based on a pivot and conformation features [72]. The aligned structures were further visualized, and the distances between the identified pharmacophores for the base compound (s) were measured by the distance wizard of PyMOL software. Finally, the protein-ligand interaction of the highest scored compounds from the selected PCA clusters was evaluated in three-dimensional space to understand the role of identified pharmacophores for stable interaction.

2.9. Molecular dynamic (MD) simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation explains time based interatomic interactions of protein with other molecular system, in a near-native condition. Such simulations are able to capture a range of biological processes such as ligand binding, complex stability, protein folding etc [73,74]. In the present study, molecular dynamic simulations for the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Native and Mutant) and its complexes with the control ligand Telaprevir and the top-ranked compounds ZINC89341287 & ZINC12128321 were performed by GROMACS-2019.2 software, as facilitated by the Simlab, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), Little Rock, USA following the procedure described in our previous paper [26]. Briefly, ligand topology files were generated by PRODRG software. Based on a triclinic grid box, the simulation was performed in SPC water and 0.15 M counter ions (Na+/Cl−) environment. NVT/NPT ensemble temperature and atmospheric pressure were set as 300 K and 1 bar, respectively. GROMOS96 43a1 force field was used for the simulation. Parrinello-Rahmanbarostat [75,76] and Parrinello-Danadio-Bussithermostat [77] algorithms were used to maintain pressure and temperature, respectively. The simulation length was set as 100 ns. Output parameters, namely Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), the radius of gyration (Rg), Root Mean Square Flexibility (RMSF) and Ligand-H bonds, were used for the evaluation of structural stability of the ligand-bound and ligand-free proteins.

2.10. Free energy analysis by MM-PBSA calculation

The free energies of protein-ligand complexes namely, Telaprevir-Native & Mutant Mpro, ZINC89341287-Native Mpro and ZINC12128321-Mutant Mpro (ΔG_Vander Waal, ΔG_Electrostatic, ΔG_Polar, ΔG_non-Polar and ΔG_Binding) were estimated by Molecular Mechanics-Poisson–Boltzmann and Solvent-Accessible surface area (MM-PBSA) method using g-mmbsa package in a 5 ns trajectory [78,79].

ΔG_Bind (KJ mol−1) was calculated by using the following formula:

| ΔG_Bind = ΔG_Comp - (ΔG_Prot + ΔG_Lig) |

Where ΔG_Comp = the energy of protein-ligand complex, ΔG_Prot and ΔG_Lig = individual energy of protein and ligand respectively.

2.11. Structural changes in the Mpro after binding of ligands

The conformational effect of ligand binding to the target proteins was evaluated by PyMOL 2.5. The distances between randomly flagged amino acids of target proteins (with and without ligands, control and top-ranking) were measured and compared by using the ‘measurement wizard’ function.

3. Results and discussion

Fig. 1 represents the overall study deign of our work.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart depicting evaluation of Astrakurkurone and its analogues against target Mpro (Native and Mutant).

3.1. Pharmacophore-based modelling of compounds from Astrakurkurone

Pharmacophore is described as the spatial arrangement of the features essential for a molecule to interact with a specific target receptor [49]. Pharmacophore modelling is a ligand-based method which is substantially being used in literature for drug discovery to identify the common descriptors such as acceptor, donor, hydrophobic and ring aromatic) in the phytochemicals under study [[80], [81], [82]]. With this technique, the structure-activity relationship of the candidate molecules can be well predicted, which shows similar functions to the candidate molecule. Pharmacophore modelling was successfully implemented for virtual screening and identifying anti-dengue compounds [83]. Similar to our previous study [35] preliminary interaction of the target protein and the compound Astrakurkurone was performed, and three principal pharmacophores (two hydrophobic groups and one acceptor functional group) were identified (Fig. 2 .). Further, based on these three identified pharmacophores, 20 Astrakurkurone analogues were screened from ZINC database. The three-dimensional structures of these twenty compounds are shown in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 2.

Interacting Pharmacophores of Astrakurkurone with the target protein Native Main Protease of SARS-CoV-2; ACC: Acceptor and HYD: Hydrophobic groups.

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional structures of the control drug Telaprevir, Astrakurkurone and twenty ZINC analogues.

3.2. Effect of residual mutations on the Mutant Mpro

Stabilization of viral protein enhances the capability of the virus to infect the host cell by providing better resistance to protein degradation [84]. The correlation between viral fitness and protein stability has been reported by many authors in the literature [85,86]. We observed a minor change in the external structure of the protein due to introduced mutations (Fig. 4 .).

Fig. 4.

Structural changes of target protein SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) due to introduction of seven-point mutations (a: Native Mpro and b: Mutant Mpro); Black arrow represents helix-coil transition.

Multiple parameters namely RSA%, Depth (Å), OSP and free energy difference (ΔΔG), were assessed to evaluate the effect of point mutations on the structural stability of the modified Mpro (Table 1 ). Literature indicated that ΔΔG can be directly correlated with the structural parameters as mentioned above [87,88]. We observed that among seven mutations introduced simultaneously, three mutations namely GLY15SER, GLY71SER and MET49THE contributed directly in increasing the stability of the protein (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of mutations on Mpr.o.

| Mutation | WT_RSA (%) | WT_Depth (Å) | WT_OSP | MT_RSA (%) | MT_Depth (Å) | MT_OSP | Predicted ΔΔG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLY15SER | 31.90 | 4.2 | 0.31 | 23.1 | 3.8 | 0.33 | 0.19* |

| THR24ALA | 102.1 | 3.2 | 0.07 | 99.4 | 3.1 | 0.11 | −0.11 |

| MET49THR | 33.1 | 4.1 | 0.32 | 36.7 | 4.0 | 0.37 | 0.43* |

| GLY71SER | 127.3 | 3.5 | 0.13 | 104.8 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 2.88* |

| LEU89PHE | 0 | 8.6 | 0.55 | 0 | 8.9 | 0.61 | −2.08 |

| LYS90ARG | 59.6 | 3.5 | 0.31 | 52.3 | 3.5 | 0.27 | −0.06 |

| PRO108SER | 19.5 | 3.8 | 0.33 | 22.8 | 3.9 | 0.31 | −0.14 |

WT: Wild Type and MT: Mutant Type, RSA (%): Relative Solvent Accessibility; OSP: Occluded Surface Packing value; ΔΔG: Predicted stability change, * increased stability.

3.3. Molecular docking

The molecular docking technique is widely used to model the interaction between small molecules and proteins at an atomic level to understand the behaviour of the small molecule in the binding site of the protein under study [64,89,90]. Researchers have studied several phytochemicals to target SARS CoV-2 Mpro through a similar technique. Rajendran et al. (2022) [91] showed two compounds from Indian cuisine, cinnamtannin B2 and cyanin, could inhibit Mpro in silico compared with the control. Similarly, natural compounds like withanoside V, and somniferine were effective against the main protease in a molecular docking experiment [92]. Similarly, Ouassaf et al. (2020) [93] reported that seven phytochemicals could inhibit SARS CoV-2 Mpro enzyme. Overall, natural compounds from the botanical source were found to have potent inhibitory protentional against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. In this study, the result of the molecular docking experiment between the target protein SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Native and Mutant) and twenty-two ligands (including control drug and Astrakurkurone) is shown in Table 2 . The docking results were further visualized in the heat map Fig. 5 . The study revealed that the control drug, Telaprevir, showed similar inhibitory responses towards both Native and Mutated Mpro (−5.9 and −6.0 kcal mol−1). However, Astrakurkurone analogues showed differential responses towards the proteins. While six ZINC analogues ZINC12128321, 36813711, 63637408, 89341287, 89970571 and 89970571 showed higher affinity towards the Native Mpro; only four compounds namely 12128321, 63637408, 1931146, and 89970571 showed promising binding affinity (≥−7.0 kcal mol−1) towards the mutant protein. We further observed that our parent compound Astrakurkurone had a low binding affinity towards the target protein Native and Mutant (−6.1 and −5.2 kcal mol−1) respectively when compared with its 20 analogues. Nevertheless, Astrakurkurone was found to be effective against the Native protein (−6.1 kcal mol−1) compared to the control drug Telaprevir (−5.9 kcal mol−1).

Table 2.

Molecular docking results (Binding affinities, Kcal mol−1) of twenty-two ligands with the target proteins (Native and Mutant Mpro).

| S/N | Compounds | Native Mpro | Mutant Mpro |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Telaprevir | −5.9 | −6.0 |

| 2 | Astrakurkurone | −6.1 | −5.2 |

| 3 | ZINC02804640 | −6.7 | −6.3 |

| 4 | ZINC06794559 | −6.4 | −6.5 |

| 5 | ZINC07967598 | −6.5 | −6.0 |

| 6 | ZINC12128321 | −7.4 | −7.3 |

| 7 | ZINC12936780 | −6.7 | −6.0 |

| 8 | ZINC14658898 | −6.2 | −6.2 |

| 9 | ZINC14746568 | −6.0 | −5.3 |

| 10 | ZINC27847390 | −5.9 | −6.2 |

| 11 | ZINC36813711 | −7.0 | −6.7 |

| 12 | ZINC40868589 | −6.2 | −6.1 |

| 13 | ZINC63362678 | −6.3 | −6.7 |

| 14 | ZINC63637408 | −7.5 | −7.0 |

| 15 | ZINC71931146 | −6.9 | −7.1 |

| 16 | ZINC86965723 | −6.3 | −5.5 |

| 17 | ZINC89341287 | −7.7 | −6.9 |

| 18 | ZINC89633127 | −6.2 | −6.2 |

| 19 | ZINC89970571 | −7.1 | −5.7 |

| 20 | ZINC89970571 | −7.3 | −7.0 |

| 21 | ZINC92123423 | −6.7 | −6.3 |

| 22 | ZINC94302879 | −5.8 | −5.5 |

Bold: higher binding affinity than the control Telaprevir (>−7.0 kcal mol−1), _: top ranking ligands.

Fig. 5.

Two coloured heat maps generated from molecular docking result (Binding Affinities-Kcal mol−1).

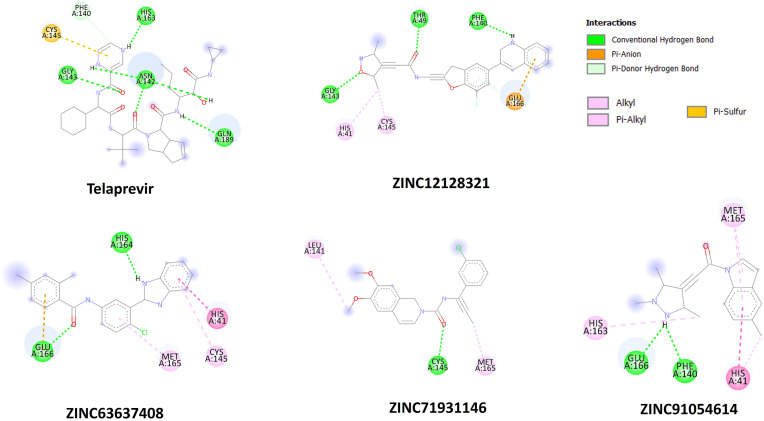

The two-dimensional residual interactions with native and mutant Mpro proteins are shown in Fig. 6, Fig. 7 . To study such interactions, the top six and four Astrakurkurone analogues were selected for native and mutated proteins, respectively, based on binding affinity ≥ −7.0 kcal mol−1. All these ZINC compounds were found to be sharing the same pocket of the target proteins (Native and Mutant) with the control Telaprevir (Table 3, Table 4 ). Among various amino acids, HIS41A of native Mpro was found to be the common residue, omnipresent in all interactions, including the control. Out of four top-ranked ZINC analogues for the mutant protein, three (ZINC12128321, ZINC63637408 and ZINC91054614) were found to be interacting with HIS41A as well. Native Mpro MET49A is present as the interacting amino acid with almost all top-ranking ligands except ZINC12128321. In contrast, mutated residue THR49A showed interaction with the ZINC121283.

Fig. 6.

Two dimensional (2D) interacting diagrams of amino acids of Native Mpro and control Telaprevir, and top ranked ZINC analogues.

Fig. 7.

Two dimensional (2D) interacting diagrams of amino acids of Mutant Mpro and control Telaprevir, and top ranked ZINC analogues.

Table 3.

Interacting amino acids between control drug, Astrakurkurone, top-ranked ZINC analogues and Native Mpro

| Compounds | Hydrogen bonds/Carbon hydrogen bonds | Alkyl Bonds | Other bonds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telaprevir | HIS41A, ASN142A, CYS145A, GLN189A | – | – |

| Astrakurkurone | GLY143A | CYS145A | |

| ZINC12128321 | ASN142A, GLY143A, SER144A, MET165A, GLU166A, GLN189A, THR190A | – | HIS164A |

| ZINC36813711 | MET49A, PHE140A, LEU141A, ASN142A, GLY143A, GLU166A | HIS41A | CYS145A |

| ZINC63637408 | HIS164A | HIS41A | MET49A, CYS145A MET165A, GLU166A, |

| ZINC89341287 | HIS41A | GLU166A | |

| ZINC89970571 | MET49A, HIS172A | – | HIS41A, PRO52A, PHE140A, LEU141A, HIS163A, MET165A, GLU166A |

| ZINC91054614 | PHE140A, GLU166A | – | HIS41A, MET49A, CYS145A, HIS163A |

Table 4.

Interacting amino acids between control drug, top-ranked ZINC analogues and Mutant Mpro

| Compounds | H bonds | Alkyl Bonds | Other bonds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telaprevir | PHE140A, ASN142A, GLY143A, HIS163A, GLN189A | – | CYS145A |

| ZINC12128321 | THR49A, PHE140A, GLY143A | – | HIS41A, CYS145A |

| ZINC63637408 | HIS164A, HIS166A, | HIS41A | CYS145A, MET165A |

| ZINC71931146 | CYS145A | – | LEU141A, MET165A |

| ZINC91054614 | PHE140A, GLU166A | HIS41A | HIS163A, MET165A |

3.4. Evaluation of drug likeliness

For drug likeliness prediction by SwissADME, along with Astrakurkurone and the control drug Telaprevir, top ranking Astrakurkurone analogues namely ZINC12128321, ZINC36813711, ZINC63637408, ZINC89341287, ZINC89970571 and ZINC91054614 were selected (Table 5 ). All the analogues showed high gastrointestinal absorption and three compounds ZINC89341287, ZINC89970571 and ZINC91054614 showed high blood-brain barrier crossing potential. Except for Telaprevir, all other compounds passed the criteria of total polar surface area (TPSA). All analogues were well within the acceptable range of 20–130 Å [94]. Lipophilicity of the candidate drugs were determined by the values of iLogP and XlogP3. While, iLOGP relies on the free solvation energies in n-octanol and water based on GB/SA (Generalized-Born and Solvent Accessible)

Table 5.

Evaluation of drug likeness by SwissADME.

| Molecule | TPSA | iLOGP | XLOGP3 | ESOL Log S | ESOL Class | GI absorption | BBB permeate | Pgp substrate | Lipinski #violations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telaprevir | 179.56 | 4.12 | 4.2 | −5.54 | Moderately soluble | Low | No | Yes | 0 |

| Astrakurkurone | 46.53 | 4.59 | 7.55 | −7.38 | Poorly soluble | Low | No | No | 0 |

| ZINC12128321 | 77.25 | 4.12 | 4.14 | −5.21 | Moderately soluble | High | No | Yes | 1 |

| ZINC36813711 | 107.2 | 2.69 | 0.83 | −2.39 | Soluble | High | No | Yes | 0 |

| ZINC63637408 | 57.04 | 3.33 | 4.1 | −5 | Moderately soluble | High | No | No | 0 |

| ZINC89341287 | 49.77 | 3.42 | 4.01 | −4.44 | Moderately soluble | High | Yes | No | 0 |

| ZINC89970571 | 54.21 | 3 | 2.51 | −3.58 | Soluble | High | Yes | Yes | 2 |

| ZINC91054614 | 38.13 | 2.73 | 2.39 | −3.29 | Soluble | High | Yes | Yes | 1 |

TPSA: Total Polar Surface Area; ESOL: Estimated Solubility; GI: Gastro-Intestinal; BBB: Blood-Brain Barrier; PgP: P-glycoprotein1.

surface area) model, XlogP3 is an automistic method with correction factors [95]. All the molecules except for Astrakurkurone passed iLogP and XlogP3 criteria (range iLOGP: 0.19 to 4.37 and XlogP3: 1.48 to 6.19) [36,96]. All compounds were found to be water soluble (LogS). P-Glycoprotein (PGP) is a membrane bound transporter which mediates the efflux of structurally unrelated compounds out of the cells thereby reducing the bioavailability of drugs [96]. We observed mixed responses for this criterion. Finally, except ZINC89970571, all other compounds passed Lipsinki's criteria (0–1).

3.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is the statistical tool for performing multivariate analysis and is used to comprehend the dimensionality of a large dataset. PCA analysis converts the dataset into multiple unrelated components, called Principal Components or PCs. PCs are orthogonal, and PC1 represents the maximum coverage of the variables, followed by PC2, PC3 etc. PCA aids in the clustering of the given dataset based on the variables [[97], [98], [99], [100]]. In our previous studies, we successfully employed the PCA tool as the primary step to cluster the compounds, thereby understand the mechanism of ligand-protein molecular interaction [36,101]. Similar to these studies, we found four clusters (C1–C4) in the PCA analysis. While the first principal component showed an 85.70% variance, the second component contributed to a 14.3% variance. Among four clusters, C1, C2, C3 and C4 consisted of four, six, six and six compounds, respectively. While C1 and C2 grouped top-ranked ligands in general, C3 and 4 had comparatively low-scoring ligands in binding affinities towards both the proteins (Native and Mutant).

Further, we observed that clustering was performed based on two parameters, the degree of binding affinities to the proteins and their responses towards native and mutant proteins independently. For example, C4, although it had a low score, similar to C1, differences in ligand responses between native and mutant proteins were marginal. On the contrary, for both the clusters C2 and C3, such differences were high (Fig. 8 .).

Fig. 8.

Principal Component Analysis based on molecular docking binding affinities (Kcal mol−1), Clusters are shown in numbering (1, 2, 3 and 4).

3.6. Pharmacophore based structural alignment

To further contemplate the common pharmacophores, the ligands of the two top-ranked clusters, namely C1 and C2, were separately aligned. The structural alignment of both clusters showed two aromatic and one acceptor group as common pharmacophores (Fig. 9 .).

Fig. 9.

PCA based structural alignment of compounds, a: PCA cluster 1 and b: PCA Cluster 2.

Further, to investigate the role of these identified pharmacophores towards the potential binding interactions with the target proteins, we selected top-ranking Astrakurkurone analogues ZINC89341287 and ZINC12128321 for Native and Mutant Mpros, respectively. Control drug Telaprevir was kept in control. The three-dimensional interactions revealed that identified pharmacophores (two aromatic and one acceptor) interacted with the target residues and other functional groups, as shown in Fig. 10 .

Fig. 10.

Visualization of pharmacophore interactions of top ranked ligands and control (a: two dimensional and b: three dimensional interactions with pharmacophores).

3.7. Molecular dynamic (MD) simulation

To understand the structural dynamics and conformational stability of protein-ligand structure in the physiological condition molecular dynamic simulation was performed for control drug and top-ranking ligand complexes (ZINC89341287-Native Mpro and ZINC12128321-Mutant Mpro). Collectively data processed from the parameters (Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), gyration and ligand-protein H bond formations) presented a similar binding profile for both, control drug Telaprevir and ligands to the target proteins (Native and Mutant). The comparative graphical representation is shown in Fig. 11 . RMSD is the measured distance between protein residues and ligands. The average RMSD values of the native complexes were 0.33, 0.28 and 0.31 nm for apo, Telaprevir-native Mpro and ZINC89341287-native Mpro, respectively. Similarly, the average RMSD values of the mutated complexes were 0.35, 0.39 and for 0.30 nm apo, Telaprevir-Mutant Mpro and ZINC12128321-Mutant Mpro, respectively. Overall, RMSD values were comparable and stable throughout the simulation for all the complexes studied. When fluctuations (RMSF) were studied, the residual fluctuation was comparatively higher for the mutated complexes, possibly due to the effect of point mutations. However, on average fluctuation stayed within the stable range of 0.1–0.7 nm for all conditions, including the apo state of the proteins. The third parameter radius of gyration (Rg), represents the compactness of the unbound and bound proteins. Overall, the Rg values for all three native sets, including the apoprotein, ranged from 2.07 to 2.26 nm. The result was indicative that the compactness of the protein was not affected due to ligand binding. All complexes maintained a minimum of one hydrogen bond throughout the simulation and went up to five hydrogen bonds on average, revealing the formation of strong ligand-protein interactions throughout the simulation. To sum up, the molecular docking simulation exercise showed that selected ligands could make effective and stable interactions with the target proteins in their respective active sites and, therefore, could inhibit the enzymatic activity of SARS-CoV-2 main protease, both for native and mutated types.

Fig. 11.

Molecular dynamic simulation of ligand-Mpro complexes, a1-d1: Native main protease (Mpro) and a2-d2: Mutant (Mut.) Mpro; a: Root Mean square Deviation (RMSD) of proteins, b: Root Mean Square Fluctuations (RMSF) of proteins, c: Radius of Gyration (Rg) of proteins and d: protein-ligand interacting hydrogen (H) bonds.

3.8. Free energy analysis by MM-PBSA calculation

Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) is an energy simulation method for measuring the binding free energy of protein-ligand complex [102,103]. Despite the high computation cost, its edges over the conventional molecular docking technique because of highly accurate results [104,105]. The results showed that when compared with the control drug Telaprevir, ZINC89341287 showed higher binding potential (ΔG binding −83.738 and −40.932 kJ mol−1 for the ligand and control, respectively) with the native protein. A similar observation was noted for the ZINC12128321-Mutant Mpro complex (ΔG binding −240.083 and −197.408 kJ mol−1 for ligand and control, respectively) (Table 6 ). All results were comparable to that the finding of the molecular docking experiment. The favourable ligand-protein complexes were also contributed by other energy parameters, namely non-polar, electrostatic and Van der Waal forces. Unfavourable polar solvation energy showed low contribution in binding. Finally, residues CYS44, SER46, LEU50, TYR118, ASN119, LEU141, ASN142 and CYS44, MET49, PRO52, MET165, LEU167, PRO168, PHE185, GLN189, THR190, ALA191 had the major contributions in the binding of control drug and ZINC89341287 towards the native Mpro (Fig. 12 .). For the mutated protein, residues THR45, SER46, PRO52, TYR118, ASN119, LEU141, ASN142 and THR25, LEU27, HIS41, VAL42, ILE43, CYS44, THR49, LEU50, ASN51, PRO52, PHE140, LEU141, ASN142, CYS145, MET165, GLN189 contributed towards the binding complex of control drug and ZINC12128321.

Table 6.

MM-PBSA calculations of binding free energy for protein-ligand complexes.

| Types of Binding Energy | Native Mpro + Control drug | Mutant Mpro + Control drug | Native Mpro + ZINC89341287 | Mutant Mpro + ZINC12128321 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG binding (KJ mol−1) | −40.932 | −197.408 | −83.738 | −240.083 |

| ΔG Non polar (KJ mol−1) | −0.494 | −21.294 | −8.846 | −21.557 |

| ΔG polar solvation (KJ mol−1) | 28.776 | 142.895 | 45.113 | 100.133 |

| ΔG Electrostatic (KJ mol−1) | −6.876 | −53.088 | −5.210 | −8.864 |

| ΔG Van der Waal (KJ mol−1) | −4.786 | −265.921 | −114.794 | −309.795 |

Fig. 12.

Contribution energy plots of interacting amino acids of target proteins (Native Mpro and Mutant Mpro) to control drug Telaprevir and selected ligands (ZINC89341287 and ZINC12128321).

3.9. Structural changes in the Mpro after binding of ligands

To understand the structural changes of Native and Mutant Mpro proteins upon binding the ligands ZINC89341287 and ZINC12128321, including the control drug Telaprevir, distances between randomly flagged amino acids were measured (Fig. 13 .). The results showed a steady increase in the distances of amino acids (Table 7 ). Such structural changes might lead to an alteration of the size of the active site of the main protease and thereby preventing further enzymatic activity.

Fig. 13.

Structural comparison with ligand free (Apo) and bound Mpro proteins, as determined by PyMol 2.0 software.

Table 7.

Distance analysis between flagged amino acids of ligand free protein and selected complexes.

| Complex | Bond Length (Å) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MET49-PRO108 | MET49-THR24 | MET49-GLY15 | THR24-LYS90 | GLY71-PRO108 | GLY15-PRO108 | |

| Native Mpro (apo) | 29.0 | 14.3 | 30.3 | 19.9 | 36.5 | 28.1 |

| Native Mpro + Telaprevir | 30.7 | 15.8 | 29.7 | 18.8 | 35.3 | 27.7 |

| Native Mpro + ZINC89341287 |

30.3 |

18.9 |

30.8 |

21.4 |

35.5 |

27.7 |

|

THR49-SER108 |

THR49-ALA24 |

THR49-SER15 |

ALA24-ARG90 |

SER71-SER108 |

SER15-SER108 |

|

| Mutant Mpro (apo) | 29.0 | 14.3 | 30.3 | 19.9 | 36.5 | 28.1 |

| Mutant Mpro + Telaprevir | 28.2 | 16.6 | 24.8 | 17.9 | 39.0 | 28.8 |

| Mutant Mpro + ZINC12128321 | 30.4 | 12.1 | 25.2 | 19.7 | 39.3 | 28.6 |

4. Conclusion

The present study reported that Astrakurkurone analogues ZINC89341287 and ZINC12128321 could inhibit native and hypothetical Mutant Mpro proteins, respectively, when compared with the control drug Telaprevir. Both the compounds showed drug-like properties and inhibited target proteins through strong interactions with the amino acids, including the substitute ones. The three-dimensional interaction also revealed that three pharmacophores, namely two aromatic and one acceptor group, contributed to the effective protein-ligand interaction. Finally, Astrakurkurone analogues ZINC89341287 and ZINC12128321 were found to form a stable complex with the respective target proteins in the near-native physiological conditions, as revealed by MD simulation.

Author contributions

A.N. conceived, designed the study & performed the experimentations; Primary data analysis & manuscript draft preparation were done by A.D. Secondary data analysis & finalization of the manuscript were done by S.S. Structural chemistry was done by T.K.L. Critical review & supervision of the work were done by K.A. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

Financial segment: This research was not funded by any government or private organisation. Authors are from three respective universities that are not going to get/loss financially from the publication. No patent or patent applications were filed, either by the authors or from the respective institutions. Non-Financial segment: Authors are not associated with any organisation that has a stake in this research publication. Declaration: Authors declare that, they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

Authors duly acknowledge Department of Life Sciences, CHRIST (Deemed to be University); Bangalore; Department of Botany, University of Calcutta, Kolkata and Department of Chemistry, Vidyasagar Metropolitan College, Kolkata for providing institutional and administrative supports as and when required.

References

- 1.Sanyaolu A., Okorie C., Hosein Z., Patidar R., Desai P., Prakash S., Jaferi U., Mangat J., Marinkovic A. vol. 14. 2021. (Global Pandemicity of COVID-19: Situation Report as of June 9, 2020, Infectious Diseases: Research and Treatment). 10.1177%2F1178633721991260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed.: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91:157. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Z., Lian X., Su X., Wu W., Marraro G.A., Zeng Y. From SARS and MERS to COVID-19: a brief summary and comparison of severe acute respiratory infections caused by three highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Respir. Res. 2020;21:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01479-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong N.S., Zheng B.J., Li Y.M., Poon L.L.M., Xie Z.H., Chan K.H., Li P.H., Tan S.Y., Chang Q., Xie J.P. Epidemiology and cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong, People's Republic of China, in February, 2003. Lancet. 2003;362:1353–1358. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14630-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zumla A., Hui D.S., Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2015;386:995–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdelrahman Z., Li M., Wang X. Comparative review of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and influenza a respiratory viruses. Front. Immunol. 2020:2309. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.552909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pal M., Berhanu G., Desalegn C., Kandi V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): an update. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.7423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J., Shi P.-Y., Li H., Zhou J. Broad spectrum antiviral agent niclosamide and its therapeutic potential. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020;6:909–915. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., Mehta A.K., Zingman B.S., Kalil A.C., Hohmann E., Chu H.Y., Luetkemeyer A., Kline S. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bansal V., Mahapure K.S., Bhurwal A., Gupta I., Hassanain S., Makadia J., Madas N., Armaly P., Singh R., Mehra I. Mortality benefit of remdesivir in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2021;7 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.606429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel T.K., Patel P.B., Barvaliya M., Saurabh M.K., Bhalla H.L., Khosla P.P. Efficacy and safety of lopinavir-ritonavir in COVID-19: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J.Infect Public Health. 2021;14:740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxena A. Drug targets for COVID-19 therapeutics: ongoing global efforts. J. Biosci. 2020;45:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s12038-020-00067-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Monica G., Bono A., Lauria A., Martorana A. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease for treatment of COVID-19: covalent inhibitors structure–activity relationship insights and evolution perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2022;19:12500–12534. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoud A., Mostafa A., Al-Karmalawy A.A., Zidan A., Abulkhair H.S., Mahmoud S.H., Shehata M., Elhefnawi M.M., Ali M.A. Telaprevir is a potential drug for repurposing against SARS-CoV-2: computational and in vitro studies. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautret P., Lagier J.-C., Parola P., Meddeb L., Mailhe M., Doudier B., Courjon J., Giordanengo V., Vieira V.E., Dupont H.T. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;56 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Devaux C.A., Rolain J.-M., Colson P., Raoult D. New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J.T., Yang Q., Gribenko A., Perrin B.S., Jr., Zhu Y., Cardin R., Liberator P.A., Anderson A.S., Hao L. Genetic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro reveals high sequence and structural conservation prior to the introduction of protease inhibitor Paxlovid. mBio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1128/mbio.00869-22. e00869-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iisu A., Granneman G., Bertz R. Ritonavir: clinical pharmacokinetics and interactions with other anti-HIV agents. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1998;35:275–291. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199835040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paintsil E., Cheng Y.C. In: Antiviral Agents, Encyclopedia of Microbiology. Schmidt T.M., editor. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White N.J., Watson J.A., Hoglund R.M., Chan X.H.S., Cheah P.Y., Tarning J. COVID-19 prevention and treatment: a critical analysis of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine clinical pharmacology. PLoS Med. 2020;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.V’kovski P., Kratzel A., Steiner S., Stalder H., Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:155–170. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariano G., Farthing R.J., Lale-Farjat S.L., Bergeron J.R. Structural characterization of SARS-CoV-2: where we are, and where we need to be. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020:344. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.605236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandey P., Rane J.S., Chatterjee A., Kumar A., Khan R., Prakash A., Ray S. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein of COVID-19 with naturally occurring phytochemicals: an in silico study for drug development. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39:6306–6316. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1796811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tai W., He L., Zhang X., Pu J., Voronin D., Jiang S., Zhou Y., Du L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020;17:613–620. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen W.-H., Hotez P.J., Bottazzi M.E. Potential for developing a SARS-CoV receptor-binding domain (RBD) recombinant protein as a heterologous human vaccine against coronavirus infectious disease (COVID)-19. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16:1239–1242. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1740560. 10.1080%2F21645515.2020.1740560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nag A., Paul S., Banerjee R., Kundu R. In silico study of some selective phytochemicals against a hypothetical SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD using molecular docking tools. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104818. Epub 2021 Aug 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Báez-Santos Y.M., John S.E.S., Mesecar A.D. The SARS-coronavirus papain-like protease: structure, function and inhibition by designed antiviral compounds. Antivir. Res. 2015;115:21–38. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daoui O., Elkhattabi S., Chtita S. Rational identification of small molecules derived from 9, 10-dihydrophenanthrene as potential inhibitors of 3CLpro enzyme for COVID-19 therapy: a computer-aided drug design approach. Struct. Chem. 2022;33:1667–1690. doi: 10.1007/s11224-022-02004-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chtita S., Belaidi S., Qais F.A., Ouassaf M., AlMogren M.M., Al-Zahrani A.A., Bakhouch M., Belhassan A., Zaki H., Bouachrine M. Unsymmetrical aromatic disulfides as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors: molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and ADME scoring investigations. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022;34 doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chtita S., Fouedjou R.T., Belaidi S., Djoumbissie L.A., Ouassaf M., Qais F.A., Bakhouch M., Efendi M., Tok T.T., Bouachrine M. In silico investigation of phytoconstituents from Cameroonian medicinal plants towards COVID-19 treatment. Struct. Chem. 2022:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11224-022-01939-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belhassan A., Chtita S., Zaki H., Alaqarbeh M., Alsakhen N., Almohtaseb F., Lakhlifi T., Bouachrine M. In silico detection of potential inhibitors from vitamins and their derivatives compounds against SARS-CoV-2 main protease by using molecular docking, molecular dynamic simulation and ADMET profiling. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1258 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belhassan A., Zaki H., Chtita S., Alaqarbeh M., Alsakhen N., Benlyas M., Lakhlifi T., Bouachrine M. Camphor, Artemisinin and sumac phytochemicals as inhibitors against COVID-19: computational approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;136 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fouedjou R.T., Chtita S., Bakhouch M., Belaidi S., Ouassaf M., Djoumbissie L.A., Tapondjou L.A., Abul Qais F. Cameroonian medicinal plants as potential candidates of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021:1–15. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1914170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nag A., Banerjee R., Paul S., Kundu R. Curcumin inhibits spike protein of new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern (VOC) Omicron, an in silico study. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022;146 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nag A., Verma P., Paul S., Kundu R. In silico analysis of the apoptotic and HPV inhibitory roles of some selected phytochemicals detected from the rhizomes of greater cardamom. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s12010-022-04006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wahab G.A., Aboelmaaty W.S., Lahloub M.F., Sallam A. In vitro and in silico studies of SARS-CoV-2 main protease M pro inhibitors isolated from Helichrysum bracteatum. RSC Adv. 2022;12:18412–18424. doi: 10.1039/D2RA01213H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ristovski J.T., Matin M.M., Kong R., Kusturica M.P., Zhang H. In vitro testing and computational analysis of specific phytochemicals with antiviral activities considering their possible applications against COVID-19. South Afr. J. Bot. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2022.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park J.-Y., Yuk H.J., Ryu H.W., Lim S.H., Kim K.S., Park K.H., Ryu Y.B., Lee W.S. Evaluation of polyphenols from Broussonetia papyrifera as coronavirus protease inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017;32:504–512. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1265519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jo S., Kim S., Shin D.H., Kim M.-S. Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CL protease by flavonoids. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020;35:145–151. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2019.1690480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giordano D., Biancaniello C., Argenio M.A., Facchiano A. Drug design by pharmacophore and virtual screening approach. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15:646. doi: 10.3390/ph15050646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aouidate A., Ghaleb A., Chtita S., Aarjane M., Ousaa A., Maghat H., Sbai A., Choukrad M., Bouachrine M., Lakhlifi T. Identification of a novel dual-target scaffold for 3CLpro and RdRp proteins of SARS-CoV-2 using 3D-similarity search, molecular docking, molecular dynamics and ADMET evaluation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39:4522–4535. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1779130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fadlalla M., Ahmed M., Ali M., Elshiekh A.A., Yousef B.A. Molecular docking as a potential approach in repurposing drugs against COVID-19: a systematic review and novel pharmacophore models. Curr.Pharmacol.Rep. 2022:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s40495-022-00285-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asadirad A., Nashibi R., Khodadadi A., Ghadiri A.A., Sadeghi M., Aminian A., Dehnavi S. Antiinflammatory potential of nano-curcumin as an alternative therapeutic agent for the treatment of mild-to-moderate hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2022;36:1023–1031. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai T.K., Biswas G., Chatterjee S., Dutta A., Pal C., Banerji J., Bhuvanesh N., Reibenspies J.H., Acharya K. Leishmanicidal and anticandidal activity of constituents of Indian edible mushroom Astraeus hygrometricus. Chem. Biodivers. 2012;9:1517–1524. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201100272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mallick S., Dey S., Mandal S., Dutta A., Mukherjee D., Biswas G., Chatterjee S., Mallick S., Lai T.K., Acharya K. A novel triterpene from Astraeus hygrometricus induces reactive oxygen species leading to death in Leishmania donovani. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:763–789. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mallick S., Dutta A., Chaudhuri A., Mukherjee D., Dey S., Halder S., Ghosh J., Mukherjee D., Sultana S.S., Biswas G. Successful therapy of murine visceral leishmaniasis with astrakurkurone, a triterpene isolated from the mushroom Astraeus hygrometricus, involves the induction of protective cell-mediated immunity and TLR9. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:2696–2708. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01943-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dasgupta A., Dey D., Ghosh D., Lai T.K., Bhuvanesh N., Dolui S., Velayutham R., Acharya K. Astrakurkurone, a sesquiterpenoid from wild edible mushroom, targets liver cancer cells by modulating bcl-2 family proteins. IUBMB Life. 2019;71:992–1002. doi: 10.1002/iub.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koes D.R., Camacho C.J. ZINCPharmer: pharmacophore search of the ZINC database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W409–W414. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. II. MMFF94 van der Waals and electrostatic parameters for intermolecular interactions. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:520–552. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. I. Basis, form, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:490–519. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. III. Molecular geometries and vibrational frequencies for MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:553–586. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halgren T.A., Nachbar R.B. Merck molecular force field. IV. Conformational energies and geometries for MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:587–615. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. V. Extension of MMFF94 using experimental data, additional computational data, and empirical rules. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:616–641. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oferkin I.V., Katkova E.V., Sulimov A.V., Kutov D.C., Sobolev S.I., Voevodin V.V., Sulimov V.B. Evaluation of docking target functions by the comprehensive investigation of protein-ligand energy minima. Advances in Bioinformatics. 2015:2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/126858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kneller D.W., Galanie S., Phillips G., O'Neill H.M., Coates L., Kovalevsky A. Malleability of the SARS-CoV-2 3CL Mpro active-site cavity facilitates binding of clinical antivirals. Structure. 2020;28:1313–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahmoud A., Mostafa A., Al-Karmalawy A.A., Zidan A., Abulkhair H.S., Mahmoud S.H., Shehata M., Elhefnawi M.M., Ali M.A. Telaprevir is a potential drug for repurposing against SARS-CoV-2: computational and in vitro studies. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forlemu N., Watkins P., Sloop J. Molecular docking of selective binding affinity of sulfonamide derivatives as potential antimalarial agents targeting the glycolytic enzymes: GAPDH, aldolase and TPI. Open J. Biophys. 2016;7:41–57. doi: 10.4236/ojbiphy.2017.71004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mótyán J.A., Mahdi M., Hoffka G., T\Hozsér J. Potential resistance of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) against protease inhibitors: lessons learned from HIV-1 protease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:3507. doi: 10.3390/ijms23073507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deller M.C., Kong L., Rupp B. Protein stability: a crystallographer's perspective. Acta Crystallogr. F: Structural Biology Communications. 2016;72:72–95. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X15024619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pandurangan A.P., Ochoa-Montaño B., Ascher D.B., Blundell T.L. SDM: a server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W229–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ratnaparkhi G.S., Varadarajan R. Thermodynamic and structural studies of cavity formation in proteins suggest that loss of packing interactions rather than the hydrophobic effect dominates the observed energetics. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12365–12374. doi: 10.1021/bi000775k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stanzione F., Giangreco I., Cole J.C. Use of molecular docking computational tools in drug discovery. Prog. Med. Chem. 2021;60:273–343. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmch.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ouassaf M., Belaidi S., Al Mogren M.M., Chtita S., Khan S.U., Htar T.T. Combined docking methods and molecular dynamics to identify effective antiviral 2, 5-diaminobenzophenonederivatives against SARS-CoV-2. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021;33 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1957712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomlinson S.M., Malmstrom R.D., Russo A., Mueller N., Pang Y.-P., Watowich S.J. Structure-based discovery of dengue virus protease inhibitors. Antivir. Res. 2009;82:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.02.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanchuk V.Y., Tanin V.O., Vovk A.I., Poda G. A new, improved hybrid scoring function for molecular docking and scoring based on AutoDock and AutoDock Vina. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2016;87:618–625. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jolliffe I.T., Cadima J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Phil. Trans. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016;374 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2015.0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lever J., Krzywinski M., Altman N. Points of significance: principal component analysis. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:641–643. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang S.-Y. Pharmacophore modeling and applications in drug discovery: challenges and recent advances. Drug Discov. Today. 2010;15:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dror O., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Inbar Y., Nussinov R., Wolfson H.J. Novel approach for efficient pharmacophore-based virtual screening: method and applications. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009;49:2333–2343. doi: 10.1021/ci900263d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Inbar Y., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Dror O., Nussinov R., Wolfson H.J. Annual International Conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Springer; 2007. Deterministic pharmacophore detection via multiple flexible alignment of drug-like molecules; pp. 412–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schneidman-Duhovny D., Dror O., Inbar Y., Nussinov R., Wolfson H.J. PharmaGist: a webserver for ligand-based pharmacophore detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W223–W228. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karplus M., McCammon J.A. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:646–652. doi: 10.1038/nsb0902-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hollingsworth S.A., Dror R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron. 2018;99:1129–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126 doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parrinello M., Rahman A. Crystal structure and pair potentials: a molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980;45:1196. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.1196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang J., Rauscher S., Nawrocki G., Ran T., Feig M., De Groot B.L., Grubmüller H., MacKerell A.D. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baker N.A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M.J., McCammon J.A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumari R., Kumar R., Lynn A. g_mmpbsa—a GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:1951–1962. doi: 10.1021/ci500020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aman L.O., Kartasasmita R.E., Tjahjono D.H. Virtual screening of curcumin analogues as DYRK2 inhibitor: pharmacophore analysis, molecular docking and dynamics, and ADME prediction. F1000Research. 2021;10:394. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.28040.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sharma M., Sharma N., Muddassir M., Rahman Q.I., Dwivedi U.N., Akhtar S. Structure-based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening and simulation studies for the identification of potent anticancerous phytochemical lead targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021:1–18. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1936178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Friday A.J., Ikpeazu V.O., Otuokere I., Igwe K.K. Targeting glycogen synthase kinase-3 (Gsk3β) with naturally occurring phytochemicals (quercetin and its modelled analogue): a pharmacophore modelling and molecular docking approach. Commun.Phys. Sci. 2020;5 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vora J., Patel S., Athar M., Sinha S., Chhabria M.T., Jha P.C., Shrivastava N. Pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation for screening and identifying anti-dengue phytocompounds. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2019.1615002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Upadhyay V., Lucas A., Panja S., Miyauchi R., Mallela K.M. Receptor binding, immune escape, and protein stability direct the natural selection of SARS-CoV-2 variants. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klein E.Y., Blumenkrantz D., Serohijos A., Shakhnovich E., Choi J.-M., Rodrigues J.V., Smith B.D., Lane A.P., Feldman A., Pekosz A. Stability of the influenza virus hemagglutinin protein correlates with evolutionary dynamics. mSphere. 2018;3 doi: 10.1128/mSphereDirect.00554-17. e00554-17 10.1128%2FmSphereDirect.00554-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang L., Jackson C.B., Mou H., Ojha A., Peng H., Quinlan B.D., Rangarajan E.S., Pan A., Vanderheiden A., Suthar M.S. SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Richards F.M., Lim W.A. An analysis of packing in the protein folding problem. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1993;26:423–498. doi: 10.1017/S0033583500002845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.DeDecker B.S., O'Brien R., Fleming P.J., Geiger J.H., Jackson S.P., Sigler P.B. The crystal structure of a hyperthermophilic archaeal TATA-box binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;264:1072–1084. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meng X.-Y., Zhang H.-X., Mezei M., Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2011;7:146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Trott O., Olson A.J., Vina AutoDock. Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rajendran M., Roy S., Ravichandran K., Mishra B., Gupta D.K., Nagarajan S., Arul Selvaraj R.C., Provaznik I. In silico screening and molecular dynamics of phytochemicals from Indian cuisine against SARS-CoV-2 MPro. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022;40:3155–3169. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1845980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shree P., Mishra P., Selvaraj C., Singh S.K., Chaube R., Garg N., Tripathi Y.B. Targeting COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) main protease through active phytochemicals of ayurvedic medicinal plants–Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha), Tinospora cordifolia (Giloy) and Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi)–a molecular docking study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022;40:190–203. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1810778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ouassaf M., Belaidi S., Chtita S., Lanez T., Abul Qais F., Md Amiruddin H. Combined molecular docking and dynamics simulations studies of natural compounds as potent inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ertl P., Rohde B., Selzer P. Fast calculation of molecular polar surface area as a sum of fragment-based contributions and its application to the prediction of drug transport properties. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:3714–3717. doi: 10.1021/jm000942e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017. 1995;7 doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Constantinides P.P., Wasan K.M. Lipid formulation strategies for enhancing intestinal transport and absorption of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate drugs: in vitro/in vivo case studies. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2007;96:235–248. doi: 10.1002/jps.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jolliffe I.T., Cadima J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Phil. Trans. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016;374 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2015.0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Abba S.I., Pham Q.B., Usman A.G., Linh N.T.T., Aliyu D.S., Nguyen Q., Bach Q.-V. Emerging evolutionary algorithm integrated with kernel principal component analysis for modeling the performance of a water treatment plant. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2020;33 doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.101081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hammoudan I., Matchi S., Bakhouch M., Belaidi S., Chtita S. QSAR modelling of peptidomimetic derivatives towards HKU4-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors against MERS-CoV. Chemistry. 2021;3:391–401. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chtita S., Belhassan A., Bakhouch M., Taourati A.I., Aouidate A., Belaidi S., Moutaabbid M., Belaaouad S., Bouachrine M., Lakhlifi T. QSAR study of unsymmetrical aromatic disulfides as potent avian SARS-CoV main protease inhibitors using quantum chemical descriptors and statistical methods. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2021;210 doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2021.104266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nag A., Paul S., Banerjee R., Kundu R. In silico study of some selective phytochemicals against a hypothetical SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD using molecular docking tools. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104818. Epub 2021 Aug 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang C., Greene D., Xiao L., Qi R., Luo R. Recent developments and applications of the MMPBSA method. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018;4:87. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang E., Sun H., Wang J., Wang Z., Liu H., Zhang J.Z., Hou T. End-point binding free energy calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: strategies and applications in drug design. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:9478–9508. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aliebrahimi S., Montasser Kouhsari S., Ostad S.N., Arab S.S., Karami L. Identification of phytochemicals targeting c-Met kinase domain using consensus docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2018;76:135–145. doi: 10.1007/s12013-017-0821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kushwaha P.P., Singh A.K., Prajapati K.S., Shuaib M., Gupta S., Kumar S. Phytochemicals present in Indian ginseng possess potential to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 virulence: a molecular docking and MD simulation study. Microb. Pathog. 2021;157 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]