Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Despite an established link between depression and higher Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk, it is unclear whether they share pathophysiology. Here, we investigated whether depression manifesting after age 50 is associated with genetic predisposition to AD.

METHODS:

From the population-based Health and Retirement Study cohort with biennial assessments of depressive symptoms and cognitive performance, we studied 6,656 individuals of European ancestry with whole-genome genotyping. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) for AD were estimated and examined for association with depression in cognitively normal participants using regression modeling.

RESULTS:

Among cognitively normal participants, those with higher AD PRS were more likely to experience depression after age 50 after accounting for effects of genetic predisposition to depression, sex, age, and education.

DISCUSSION:

Genetic predisposition to AD may be one of the factors contributing to the pathogenesis of mid-life depression. Whether there is a shared genetic basis between mid-life depression and AD merits further study.

Keywords: Mid-life depression, polygenic risk score, Alzheimer’s disease, population-based prospective cohort

Community-based prospective cohort studies have found that depression, either mid-life or late-life depression, was associated with two-fold higher risk for subsequent development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or vascular dementia1–6. The prospective studies in late-life depression were conducted in about 50,000 community-based participants who had depression in the absence of dementia at baseline and were followed over time for a median of 5 years4. Late-life depression in those studies referred to depression manifesting after age 504 (in 11 studies) or after age 602 (in 12 studies) regardless of the onset age. These studies suggest that depression, particularly late-life depression, may be a risk factor for or a prodrome of AD, or a combination of both.

Recently, leveraging results from large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of depression and AD, respectively, a study found that depression and AD have a shared genetic basis7. Consistently, greater genetic liability to depression, as reflected by a higher depression polygenic risk score (PRS), has been found to be associated with a faster decline of episodic memory over time7 and higher rate of converting from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to AD8. The shared genetic architecture between depression and AD is in line with observations that up to 50% of individuals with mild cognitive impairment or AD experience depressive symptoms9,10. It is unknown, however, whether genetic liability to AD contributes to depression, particularly mid-life depression, and this question is the focus of this study.

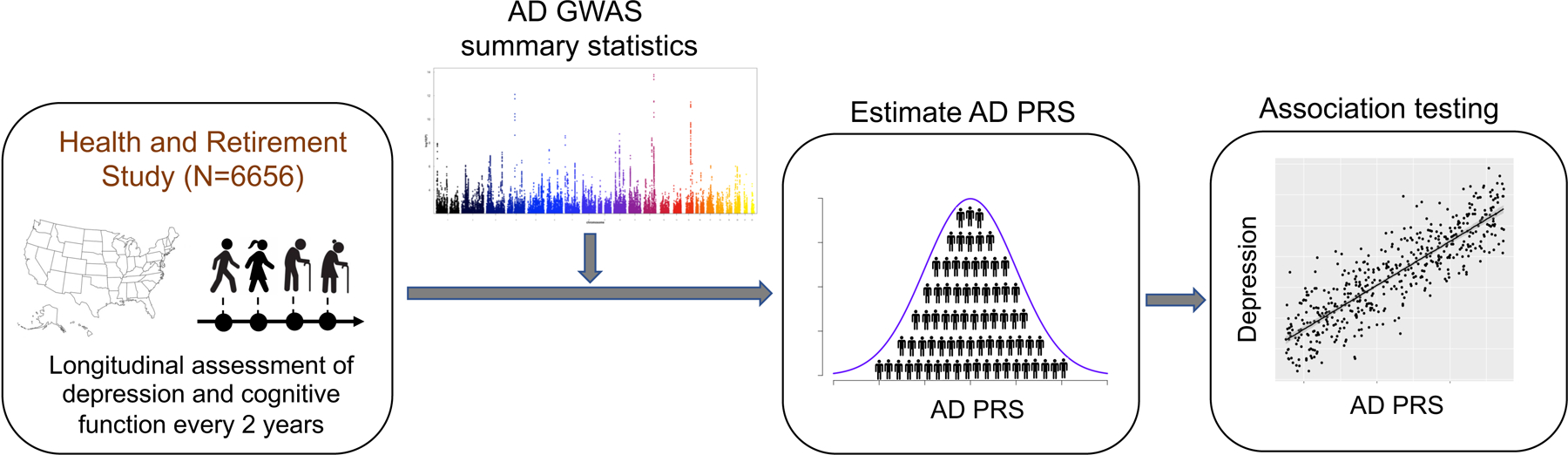

AD has a long preclinical or prodromal period of up to 20 years, during which time, pathologies accumulate despite no or very mild cognitive symptoms11,12. The prodromal period is typically between age 50 and 7011,12. If mid-life depression is a feature of prodromal AD, then the genetic liability to AD would be associated with depression manifesting during the prodromal period for AD, which is between 50 and 70 years of age. Hence, we aimed to investigate whether depression manifesting after age 50 and before the manifestation of cognitive impairment is associated with genetic liability to AD. To this end, we tested whether AD PRS is associated with depression manifesting after age 50 among cognitively normal individuals from the population-based Health and Retirement Study (HRS) cohort, who had biennial assessments of depressive symptoms and cognitive performance for up to 21 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Study design

METHODS

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) cohort

The HRS is longitudinal survey of ageing in the U.S. that has been conducted every 2 years since 199213. The HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan14. HRS was designed to be a national representative cohort of Americans over age 50 and all participants provided written informed consent for the HRS13. We focused our analyses on participants who had genetic data, were 50 years or older, cognitively normal at their initial assessment and were of European ancestry. We focused on participants of European ancestry due to limited power in other ancestry groups and lack of ancestry-specific GWAS for AD and for depression to accurately estimate their PRS. A total of 6656 participants were included in the analysis.

Cognitive functioning in HRS participants was assessed every 2 years either over the phone or in-person using a modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (mTICS)15, which included 10-word immediate and delayed recall (0–20 points; assessing memory), serial 7 subtraction (0–5 points; assessing working memory), and backward counting (0–2 points; assessing attention and processing speed)15. The composite score from the mTICS can range from 0 to 27, with higher score reflecting better cognitive function. For the years when backward counting contained only one task instead of two (2004–2008, 2014, 2016), the mTICS composite score can range from 0 to 26. Following the psychometrically validated cut-points developed by Langa and Weir15, we classified participants scoring 0 to 6 as having cognitive impairment (probable dementia), 7 to 11 as having cognitive impairment (probable mild cognitive impairment (MCI)), and 12–27 as having normal cognition for each of the follow-up years. The cognitive status was used to exclude depressive symptom scores reported at the visits that participants were found to have cognitive impairment (i.e., probable MCI or dementia) and from subsequent visits as described in more detail below.

Depressive symptoms in HRS were assessed every two years, between 1996 to 2016, using the psychometrically validated 8-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression (CES-D) scale16. The CES-D total score ranges from 0 to 8, with higher scores reflecting more depressive symptoms. Only participants who responded to all 8 questions at each assessment were included for assessment of depression. For each HRS participant, the average CES-D score during normal cognition was calculated using the CES-D scores from visits with normal cognition, as reflected a by TICS score ≥ 12. Participants were categorized into with or without likely clinically significant depression using the psychometrically determined threshold of 3 for the CES-D17,18 (i.e., an average CES-D ≥ 3 is likely significant depression and an average CES-D < 3 is likely without significant depression). Of note, we censored out the CES-D scores at the visit that participants had a TICS score <12 and from all subsequent visits. Therefore, the depressive symptoms included in our analyses are those from the years that participants had normal cognitive performance.

Genome-wide genotyping in the HRS cohort

We utilized all the publicly available genome-wide genotyping from the HRS, which included datasets from phases 1–3 in 15,708 participants. Participants in phases 1 and 2 were genotyped on the Illumina HumanOmni2.5–4v1 array and in phase 3 on the Illumina HumanOmni2.5–8v1 array. Genotypes for the combined datasets, including 2,315,518 overlapping, non-discordant SNPs, were downloaded from dbGaP. We performed additional quality control on the obtained genotype data using PLINK v.1.90b5319. We excluded subjects with an overall genotyping missingness >10%, sex mismatches, or being closer than second-degree relatives. Additionally, we removed variants with evidence of deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p < 10−7), missing genotype rate >10%, minor allele frequency < 1%, or being ambiguous variants. We performed multidimensional scaling analysis to compare ancestry of self-report White to CEU (i.e., U.S. Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe) from the HapMap Project20 and kept only participants close to HapMap CEU samples (within 6 standard deviations). We performed imputation using the 1000 Genome Project Phase 321 and the Michigan Imputation Server22. SNPs with imputation R2 > 0.8 were retained. After all the quality control steps, we retained genotypes for 9,102 participants of European ancestry. After selecting participants with normal cognition at baseline (based on mTICS), consistent progression of cognitive performance without back-and-forth fluctuation of cognitive status, and available longitudinal depressive symptom scores, there was a total of 6656 individuals to include in the analysis.

Calculation of polygenic risk score (PRS)

A PRS is an estimate of an individual’s cumulative genetic predisposition to a trait or disease. Practically, PRS is a weighted sum of the individual’s genotypic profile weighted by effect-size estimates from a GWAS of the trait of interest23,24. We calculated PRSs using the PRSice-2 software23 and its default parameters. PRSice-2 uses summary association statistics from a base data and genome-wide genotyping from a target sample. Only SNPs with GWAS association p-values below a certain threshold are included in the estimation of the PRS and all other SNPs are excluded23,24. Since the optimal p-value threshold is unknown a priori, the PRS was calculated over a range of thresholds, and association of a PRS with a trait was tested for each threshold accordingly. The GWAS p-value thresholds were selected with an interval of 5e-05, with the minimum threshold of 5e-08, and maximum threshold of 0.5. Clumping was performed to retain SNPs with the smallest p value within a 250-kb window and exclude SNPs that were in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.1).

To calculate the PRS for AD, we used the AD GWAS25 in 21,982 AD cases and 41,944 cognitively normal controls of European ancestry, which has 11,480,633 SNPs, as the base data. The rationale for using this AD GWAS was that it only included AD case-controls based on clinical assessment, which limits the heterogeneity of the outcome. Importantly, it has greater SNP-based heritability than that of the larger AD GWAS that included both AD cases and AD-by-proxy based on family history of dementia26 (6.4% versus 1.2%) and is thus better base data for estimating PRS24. For the depression PRS estimation, we used the depression GWAS in 807,553 participants of European descent27. We used the same genome build, GRCh37, for the base and target data. Of note, none of the HRS participants were part of the AD GWAS25 or depression GWAS27 that we used as the training datasets. Since we aimed to investigate association between AD genetic burden and depression manifesting after age 50 among cognitively normal persons, we excluded HRS participants with both depression and cognitive impairment (i.e., probable MCI or dementia) from all the analyses.

In our specificity analyses, PRS for different brain traits were estimated for HRS participants using results from GWAS of participants of European ancestry for the following conditions: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; 20,806 cases and 59,804 controls)28, Parkinson’s disease (PD; 482,730 participants)28, intracranial aneurysm (7,495 cases and 71,934 controls)29, and neuroticism (390,278 participants)30.

Statistical analysis

Association between the depression PRS and clinically significant depression was examined with logistic regression, in which depression was the outcome, depression PRS the independent variable, and sex, age, education, ten genetic principal components, and genotyping chip as covariates. Permutation procedure (n=10,000), as implemented by PRSice-223, was performed to optimize the parameters for PRS calculation, maximize the fit, and maintain appropriate type I error24, and empirical p-value through permutation was calculated. Likewise, association between the AD PRS and depression was examined with logistic regression, adjusting for depression PRS, sex, age, education, ten genetic principal components, and chip. Subsequently, an empirical p-value was estimated using 10,000 permutations.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the HRS cohort

The study consisted of 6656 participants from HRS with normal cognition at baseline and available genotyping. Their median age was 56, and 75% of the participants were between age 50 and 65 at baseline, which is the typical prodromal age of AD (Table 1). Women made up 59% of the participants, and educational attainment ranged from 33% with high-school education, 26% with some college education, and 31% with college or higher level of education. The participants were followed for a median of 16 years (range [2 – 21]; Table 1). Over the course of the study, 1.3% and 2.0% of the participants developed cognitive impairment (either probable MCI or dementia) at the first and second follow-up visit, respectively, and cumulatively, 15.6% developed cognitive impairment by the last visit (Table 1). Over the follow-up duration, 9.4% of the participants met criteria for clinically significant depression (referred to as depression henceforth), which is consistent with the prevalence of depression in the community for people over 50 years of age31. By censoring individuals as they developed cognitive impairment, only longitudinal depressive symptoms from participants with normal cognition was considered.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the 6656 HRS participants

| Characteristics | Mean / Median / Range |

|---|---|

| Age at baseline | 59.3 / 56.0 / 50.0 – 97.0 |

| Age at last visit | 72.5 / 73.0 / 50.0 – 107 |

| Number of follow-up visits | 7.6 / 8.0 / 1.0 – 11.0 |

| Number of follow-up years | 15.2 / 16.0 / 2.0 – 22.0 |

| Depression score | |

| Average over all follow-up years before cognitive impairment | 1.1 / 0.7 / 0.0–8.0 |

| At baseline | 1.0 / 0.0 / 0.0–8.0 |

| Characteristics | N (%) |

| Sex (female) | 3912 (58.8) |

| Race (European ancestry) | 6656 (100.0) |

| Education* | |

| Less than HS/GED | 626 (9.4) |

| HS/GED | 2217 (33.3) |

| Some college | 1718 (25.8) |

| College graduate | 994 (14.9) |

| Post-college | 1079 (16.2) |

| Cognitive status | |

| At baseline | |

| Normal | 6656 (100.0) |

| Impaired | 0 (0.0) |

| At follow-up visit 1 | |

| Normal | 6515 (98.6) |

| Impaired | 90 (1.3) |

| At follow-up visit 2 | |

| Normal | 6354 (97.9) |

| Impaired | 134 (2.0) |

| At the last visit | |

| Normal | 5257 (83.4) |

| Impaired | 1042 (15.6) |

| Depression (average of all follow-up years before cognitive impairment) | |

| Case | 626 (9.4) |

| Control | 6030 (90.6) |

HRS: Health and Retirement Study; HS: high school; GED: Graduate Equivalency Degree

There were 6656 participants at baseline and all had normal cognition. Of these, 51 dropped out after the baseline visit, 117 dropped out after the first follow-up visit, and thereafter, 189 dropped out at different follow-up visits. The “last visit” here refers to the last visit for a particular participant; it can be follow-up visit 6 for some, or follow-up visit 7 or 8 for others.

Participants experiencing depression were more likely to develop cognitive impairment

We found that among cognitively normal participants, those who experienced clinically significant depression during the follow-up years were more likely to develop cognitive impairment (i.e., probable MCI or dementia) in the subsequent years after adjusting for age, sex, and education (OR = 1.5; p = 0.0007; N = 6656). Here, depression refers to clinically significant depression experienced during the follow-up years (between age 50 and 70) while the participants had normal cognitive performance.

Participants with higher depression PRS were more likely to experience depression

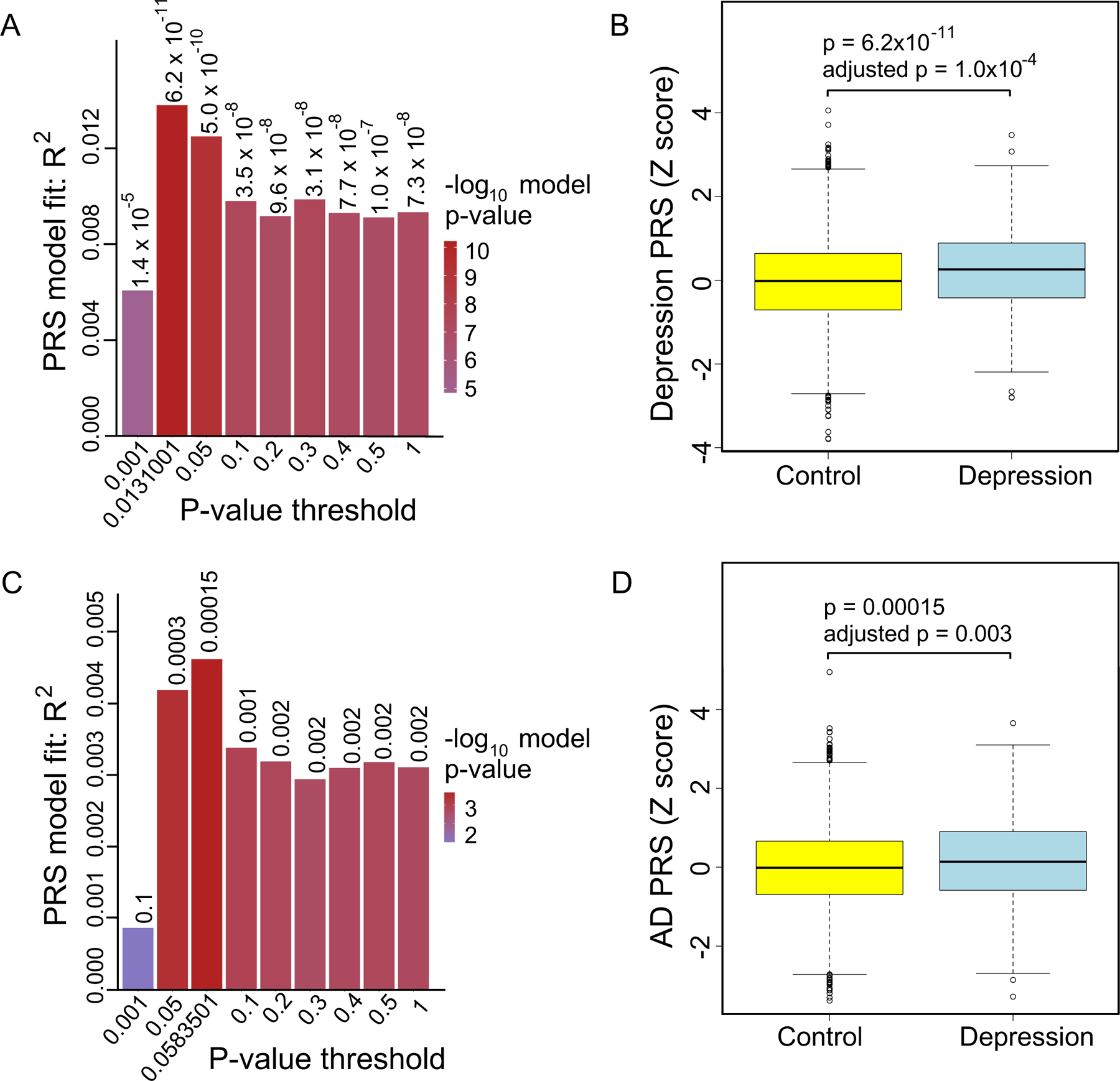

Among cognitively normal HRS participants, those with higher depression PRS were more likely to experience depression after age 50 after accounting for effects of sex and population substructure (p = 6.2 × 10−11; permuted p = 1.0 × 10−4; GWAS p-value threshold = 0.0131001; beta-coefficient = 5803, N = 6656; Figure 2A, B). As expected, participants with higher cumulative genetic burden for depression were more likely to experience depression.

Figure 2: Association between depression and depression PRS and AD PRS, respectively, in cognitively normal participants of the HRS cohort.

A. PRS model fit and GWAS p-value thresholds for associations between depression PRS and depression. B. Association between the depression PRS (estimated with the GWAS p-value threshold of 0.0131001) and depression. C. PRS model fit and p-value thresholds for associations between AD PRS and depression. D. Association between AD PRS (estimated using the GWAS p-value threshold of 0.0583501) and depression.

Participants with higher AD PRS were more likely to develop cognitive impairment

We found that participants with a greater genetic liability to dementia, as reflected by a higher AD PRS, were more likely to develop cognitive impairment - either probable MCI or dementia - during the follow-up years after accounting for effects of sex, age, education, and population substructure (beta = 17.8; p = 7.5 × 10−10; permuted p = 1.0 × 10−4; N = 6656).

Cognitively normal participants with higher AD PRS were more likely to experience depression

In examining the relationship between AD PRS and depression, we found that among cognitively normal participants, those with higher AD PRS were more likely to experience depression after age 50 after adjusting for sex, ten genetic principal components, and genotyping array (p = 1.5 × 10−4; permuted p = 0.003; GWAS p-value threshold = 0.0583501; beta = 1831, N=6656; Figure 2C, D). This association remained significant after adjusting simultaneously for sex, age, education, ten genetic principal components, and genotyping array (beta = 1627; p = 0.00086; GWAS p-value threshold = 0.0583501; N = 6656). Moreover, cognitively normal persons with higher AD PRS were more likely to experience depression after age 50 even after adjusting for the depression PRS in addition to sex and population substructure (p = 2.7 × 10−4; permuted p = 0.004; GWAS p-value threshold = 0.0583501; beta = 1762; N = 6656).

The association between the AD PRS and depression was not explained by the APOE E4 allele, which is the strongest genetic risk factor for AD. APOE E4 allele was not significantly associated with depression (p = 0.08) despite being correlated with the AD PRS (correlation rho = 0.14; p=1.0 × 10−30; N = 6656). The AD PRS and depression PRS were modestly correlated (rho = 0.03, p = 0.008; N = 6656). Together, these results suggest that cumulative genetic liability to AD contributes to depression after age 50 in cognitively normal persons independently of their genetic liability to depression.

Specificity of the association between AD PRS and depression

To determine the specificity of the association between depression and AD PRS, we examined the association between depression and genetic liability to other neurologic and psychiatric traits, including ALS, Parkinson’s disease, intracranial aneurysm, and neuroticism in the HRS cohort. We found no association between the ALS PRS and depression (p = 0.05; permuted p = 0.41; N = 6656), no association between Parkinson’s disease PRS and depression (p = 0.05; permuted p = 0.42; N = 6656), and no association between intracranial aneurysm PRS and depression (p = 0.01; permuted p = 0.13; N = 6656). However, we found a strong association between neuroticism PRS and depression (p = 9.3 × 10−8; permuted p = 9.9 × 10−5; N = 6656), which is as expected since neuroticism is a personality trait that predisposes to depression. Additionally, AD and neuroticism were significantly correlated based on results of LD score regression26. These results reflect the specificity of the association between AD PRS and depression in people over age 50 with normal cognition.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to show that cumulative genetic burden for AD, estimated from common alleles, is associated with depression after age 50 in cognitively unimpaired individuals. Additionally, the association between the AD PRS and depression was independent of the genetic liability for depression. Notably, depression was based on longitudinal biennial assessment for up to 21 years (median: 16; range 2 to 21) and only considered in participants with normal cognitive performance to avoid effects incipient MCI or dementia could have on depression. These findings suggest that depression manifesting after age 50 in cognitively normal persons may represent one of the early signs of prodrome for future cognitive decline and may signify an increased risk for subsequent development of AD. Furthermore, it raises an important question of whether treating depression manifesting after age 50 in cognitively normal persons can alter the risk for subsequent development of AD.

These novel findings are notable considering that we found well-established and expected associations between depression and cognitive impairment in this population based HRS cohort. First, individuals with depression had higher odds of developing cognitive impairment. This finding is consistent with community-based prospective cohort studies that show that older adults with more depressive symptoms are more likely to develop dementia32. Second, as expected, we found that individuals with higher PRS for depression were more likely to experience depression, and individuals with higher PRS for AD were more likely to develop cognitive impairment. These expected results provide more confidence in the finding that cognitively normal persons with higher AD PRS were more likely to experience depression after age 50 after accounting for sex, age, education, and cumulative genetic predisposition for depression. Together, these findings suggest some common genetic basis between depression and AD33.

The results should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. First, we focused on participants of European ancestry due to the lack of sufficiently powered GWAS among individuals of non-European ancestry. This might limit the generalizability of the findings to individuals of European descent. Second, the only available large-scale measure of cognitive performance in HRS was mTICs, which precludes a detailed classification of cognitive dysfunction; however, the cutoff score threshold we used was based on the Langa-Weir recommended score that has been psychometrically validated and shown to have 87.2% concordance with the classification based on the detailed psychological testing in this HRS cohort15. Third, self-report depression may miss individuals who under-report their depression; however, self-report CES-D scales have high sensitivity in detecting depression (83%) compared to clinician diagnosed depression18. Furthermore, self-report depressive symptoms and clinically diagnosed major depression have highly overlapping genetic architecture, as reflected by a high genetic correlation (at least 0.85)27. Fourth, in this study, there is no data to discern whether the reported depressive symptoms represent new or recurrent depressive symptoms. However, this limitation was partially mitigated by adjusting for the genetic burden for depression as reflected by the depression PRS.

This study has several strengths. First, our primary analysis was of a population-based national representative cohort of 6656 Americans aged 50 or older. This cohort is optimal for examining whether depression is a prodrome for future AD since all participants had normal cognitive performance at baseline and 75% were between age 50 and 64, which is the typical time window for a prodromal period for AD. Second, depression and cognitive performance were longitudinally assessed, every two years, for up to 21 years. Third, individuals who developed cognitive impairment during the study were censored from the analysis so that only depressive symptoms reported during periods of normal cognition were considered. Fourth, the rate of cognitive impairment was consistent with estimates from the literature34, aiding the generalizability of these findings.

In summary, cumulative genetic risk of AD may be one of the factors contributing to the pathogenesis of depression manifesting after age 50 in cognitively normal persons, which, in turn, may be an early sign of prodrome of AD and a target for screening and early treatment to prevent future cognitive decline.

Research in context.

Systematic review:

While many epidemiologic studies have found that mid-life or late-life depression is associated with higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), it is unclear whether depression manifesting after age 50 in cognitively normal persons may be a prodrome for AD.

Interpretation:

Here, we found that among cognitively normal persons, those with a greater AD genetic burden were more likely to experience depression between ages 50 and 70, which is the typical prodromal period for AD, independently of the genetic burden for depression and of other factors. This suggests that depression manifesting after age 50 may be an early prodrome of future cognitive decline in some people.

Future directions:

The shared diathesis between mid-life depression and AD merits further examination. Additionally, future studies should investigate whether treating mid-life depression mitigates AD risk.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the participants and researchers of HRS and EBHS for their time and efforts.

Funding sources

The following Veterans Administration grants supported this work: I01 BX003853 (APW), IK4 BX005219 (APW), I01 BX005686 (APW). The following NIH grants supported this work: R01 AG056533 (TSW and APW); R01 AG070937 (JJL); P30 AG066511 (AIL); R56 AG062256 (TSW).

APW is also supported by U01 MH115484; R01 AG071170. TSW is also supported by U54AG065187; U01 AG061357.

The views expressed in this work do not necessarily represent the views of the Veterans Administration or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: none

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Archives of general psychiatry. May 2006;63(5):530–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers AL, Yaffe K. Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nature reviews Neurology. May 3 2011;7(6):323–31. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. The Lancet Neurology. Sep 2011;10(9):819–28. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70072-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF 3rd. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. May 2013;202(5):329–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Middleton LT, Ioannidis JP, Evangelou E. Systematic evaluation of the associations between environmental risk factors and dementia: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Sep 3 2016;doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richmond-Rakerd LS, D’Souza S, Milne BJ, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Longitudinal Associations of Mental Disorders With Dementia: 30-Year Analysis of 1.7 Million New Zealand Citizens. JAMA psychiatry. Feb 16 2022;doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harerimana NV, Liu Y, Gerasimov ES, et al. Depression contributes to Alzheimer’s disease through shared genetic risk. Biological psychiatry. in press; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J, Li Q, Qin W, et al. Neurobiological substrates underlying the effect of genomic risk for depression on the conversion of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain : a journal of neurology. Dec 1 2018;141(12):3457–3471. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher D, Fischer CE, Iaboni A. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. Mar 2017;62(3):161–169. doi: 10.1177/0706743716648296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Linde RM, Dening T, Stephan BC, Prina AM, Evans E, Brayne C. Longitudinal course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. Nov 2016;209(5):366–377. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.148403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet (London, England). Jul 30 2016;388(10043):505–17. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01124-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabin LA, Smart CM, Amariglio RE. Subjective Cognitive Decline in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Annual review of clinical psychology. May 8 2017;13:369–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort Profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol Apr 2014;43(2):576–85. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Data from: Health and Retirement Study, genome-wide genotyping public use dataset. Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740). Ann Arbor, MI, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci Jul 2011;66 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i162–71. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briggs R, Carey D, O’Halloran AM, Kenny RA, Kennelly SP. Validation of the 8-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in a cohort of community-dwelling older people: data from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Eur Geriatr Med Feb 2018;9(1):121–126. doi: 10.1007/s41999-017-0016-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Capuano AW, et al. Late-life depression is not associated with dementia-related pathology. Neuropsychology. Feb 2016;30(2):135–42. doi: 10.1037/neu0000223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, Alonso J. Screening for Depression in the General Population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2016;11(5):e0155431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet Sep 2007;81(3):559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The International HapMap Project. Nature. Dec 18 2003;426(6968):789–96. doi: 10.1038/nature02168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. Nov 1 2012;491(7422):56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das S, Forer L, Schonherr S, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nature genetics. Oct 2016;48(10):1284–1287. doi: 10.1038/ng.3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SW, O’Reilly PF. PRSice-2: Polygenic Risk Score software for biobank-scale data. Gigascience. Jul 1 2019;8(7)doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi SW, Mak TS, O’Reilly PF. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nature protocols. Sep 2020;15(9):2759–2772. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0353-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nature genetics. Mar 2019;51(3):414–430. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nature genetics. Mar 2019;51(3):404–413. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nature neuroscience. Mar 2019;22(3):343–352. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolas A, Kenna KP, Renton AE, et al. Genome-wide Analyses Identify KIF5A as a Novel ALS Gene. Neuron Mar 21 2018;97(6):1268–1283.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakker MK, van der Spek RAA, van Rheenen W, et al. Genome-wide association study of intracranial aneurysms identifies 17 risk loci and genetic overlap with clinical risk factors. Nat Genet Dec 2020;52(12):1303–1313. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00725-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagel M, Jansen PR, Stringer S, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nature genetics. Jul 2018;50(7):920–927. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0151-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lotfaliany M, Hoare E, Jacka FN, Kowal P, Berk M, Mohebbi M. Variation in the prevalence of depression and patterns of association, sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in community-dwelling older adults in six low- and middle-income countries. Journal of affective disorders. May 15 2019;251:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaup AR, Byers AL, Falvey C, et al. Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults and Risk of Dementia. JAMA psychiatry May 1 2016;73(5):525–31. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wingo TS, Liu Y, Gerasimov ES, et al. Shared mechanisms across the major psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. in review; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Gillis C, Mirzaei F, Potashman M, Ikram MA, Maserejian N. The incidence of mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and data synthesis. Alzheimer’s & dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands). Dec 2019;11:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]