Abstract

Objective

To evaluate, using an online non-probability sample, the beliefs about and attitudes towards cancer prevention of people professing vaccination scepticism or conspiracy theories.

Design

Cross sectional survey.

Setting

Data collected mainly from ForoCoches (a well known Spanish forum) and other platforms, including Reddit (English), 4Chan (English), HispaChan (Spanish), and a Spanish language website for cancer prevention (mejorsincancer.org) from January to March 2022.

Participants

Among 1494 responders, 209 were unvaccinated against covid-19, 112 preferred alternative rather than conventional medicine, and 62 reported flat earth or reptilian beliefs.

Main outcome measures

Cancer beliefs assessed using the Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) and Cancer Awareness Measure Mythical Causes Scale (CAM-MYCS) (both validated tools).

Results

Awareness of the actual causes of cancer was greater (median CAM score 63.6%) than that of mythical causes (41.7%). The most endorsed mythical causes of cancer were eating food containing additives or sweeteners, feeling stressed, and eating genetically modified food. Awareness of the actual and mythical causes of cancer among the unvaccinated, alternative medicine, and conspiracy groups was lower than among their counterparts. A median of 54.5% of the actual causes was accurately identified among each of the unvaccinated, alternative medicine, and conspiracy groups, and a median of 63.6% was identified in each of the three corresponding counterparts (P=0.13, 0.04, and 0.003, respectively). For mythical causes, medians of 25.0%, 16.7%, and 16.7% were accurately identified in the unvaccinated, alternative medicine, and conspiracy groups, respectively; a median of 41.7% was identified in each of the three corresponding counterparts (P<0.001 in adjusted models for all comparisons). In total, 673 (45.0%) participants agreed with the statement “It seems like everything causes cancer.” No significant differences were observed among the unvaccinated (44.0%), conspiracist (41.9%), or alternative medicine groups (35.7%), compared with their counterparts (45.2%, 45.7%, and 45.8%, respectively).

Conclusions

Almost half of the participants agreed that “It seems like everything causes cancer,” which highlights the difficulty that society encounters in differentiating actual and mythical causes owing to mass information. People who believed in conspiracies, rejected the covid-19 vaccine, or preferred alternative medicine were more likely to endorse the mythical causes of cancer than their counterparts but were less likely to endorse the actual causes of cancer. These results suggest a direct connection between digital misinformation and consequent erroneous health decisions, which may represent a further preventable fraction of cancer.

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020.1 Between 30% and 50% of diagnosed cancer is preventable through lifestyle changes and existing evidence based prevention strategies,2 such as maintaining a healthy weight, partaking in physical activity, eating fruits and vegetables, limiting consumption of alcohol and red and processed meat, avoiding excess sun exposure and active and passive smoking, and participating in vaccination programmes against human papillomavirus and hepatitis.3 4 Adherence to recommendations on cancer prevention is directly related to beliefs about cancer. Therefore, identifying these beliefs and their underlying factors can help to inform prevention efforts.5

Although communication technologies and social media provide new opportunities to access health information, they also have a pervasive effect. They open a direct avenue of misinformation (false information that is spread, regardless of intent to mislead) and disinformation (misinformation that is circulated intentionally for secondary gains—namely, money, reputation, or power), posing health concerns.6 7 Conspiracy beliefs are the extreme results of misinformation and widespread suspicions of the real world. These include the beliefs that the earth is flat, that humanoids take reptilian forms to manipulate human societies, or that condensation trails from planes are “chemtrails” comprising agents sprayed for evil purposes.8 9 Some myths also relate to Santa Claus—some people think that Santa is an anagram of Satan and brings corruption and greed during Christmas, whereas others believe that Santa Claus is a giant lie that was started by the Illuminati for mind control.10 The covid-19 pandemic also caused multiple conspiracies, mainly related to its origin and vaccines, undermining preventive health responses and leading some people to undertake risky alternative treatments.11

Increasing misinformation on the internet and its dissemination patterns have promoted narratives that affect real world health outcomes. Misinformation about cancer can lead to increased disease burden because of people’s refusal to adopt effective preventive health measures (for instance, making cancer promoting lifestyle choices or rejecting human papillomavirus vaccines). It can also lead to delays in seeking effective oncological treatment and, consequently, worsen the outcomes in patients with cancer. Misinformation is also associated with avoidable social suffering. For instance, conspiracy theories may produce intense fear related to malevolent reptilians, mortal side effects of vaccines, or inhalation of ubiquitous toxins. People can also encounter social stigma when they endorse conspiracy theories.12 Social media algorithms promote the aggregation of users, who may share a broader health related magical world view. Health world views that dismiss scientific knowledge in support of magical thinking were previously associated with vaccination scepticism.13 However, no data exist on endorsement of conspiracies or vaccination scepticism in relation to individuals’ beliefs about and attitudes to cancer prevention. We did this study to evaluate beliefs about and attitudes to cancer prevention based on health preferences and conspiracy beliefs.

Methods

Study design

We collected data anonymously using a cross sectional design, with an online survey distributed on several platforms. Data mainly came from ForoCoches (https://forocoches.com/), a well known and influential Spanish forum.14 15 The administrators of ForoCoches granted us access to publish a post on their website for this research. We also posted the survey on other websites such as Reddit and 4Chan. Reddit (https://www.reddit.com/) is an English language discussion website on which registered members submit content that is upvoted or downvoted by other members. Reddit works with a reputation system that provides better visibility when the member has more points (called “karma”) based on the voting system. 4Chan (https://www.4chan.org/) is a registration-free English language platform on which users typically post anonymously. We also posted the survey on HispaChan (https://www.hispachan.org/), which is equivalent to 4Chan in Spanish, and other influential forums according to Alexa ranking site (used as a metric to determine the popularity of a site), including MediaVida (https://www.mediavida.com/), Burbuja Info (https://www.burbuja.info/), and Taringa (https://www.taringa.net/), which are similar to ForoCoches but with smaller audiences. The survey was also posted in certain Telegram groups with titles including words such as “anti-vaxxers,” “reptilians,” and “flat earth.” Finally, the survey was distributed on the website Mejor Sin Cáncer (“Better Without Cancer” in Spanish; https://mejorsincancer.org/), a Spanish language website on cancer prevention created in 2015 that we manage; it receives approximately 300 daily visits, mainly via search engines (98% of visits). We created a pop-up advertisement to invite visitors to participate in this survey. We applied no exclusion criteria. We collected the study data by using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Catalan Institute of Oncology.16 17

Measures

Sociodemographics, health behaviours, and conspiracy beliefs

A copy of the survey is provided in the supplementary material. We asked the participants to provide information on their age, sex, country of birth, country of residence, education level, and whether their occupation was related to the medical field. Questions on health habits and behaviours included a preference for conventional or alternative medicines, administration of any covid-19 vaccine, the reason for not undergoing vaccination, smoking status, alcohol consumption, weight and height, and personal history of cancer.

We asked the participants if they considered the Earth to be round or flat, with four response options (I have always considered the Earth to be round (spherical or similar); I always thought that the Earth was round (spherical or similar) but recently I have had doubts; I had always thought the Earth was flat, but recently I have had doubts; I have always considered the Earth to be flat). We included two questions to assess reptilian conspiracy beliefs, using the statements “there are many shape shifting lizards taking human forms or turning into reptilian humanoids” and “presidents of most countries are reptilian humanoids.” The response options were based on a five point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree, disagree, unsure, agree, and strongly agree). We included participants in the “conspiracy group” if they marked options other than “I have always considered the Earth to be round (spherical or similar),” or if they agreed or strongly agreed with either of the two questions on reptilians.

Cancer beliefs

To assess their beliefs about actual and mythical (non-established) causes of cancer, we presented the participants with the closed risk factor questions on the validated scales—the Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) and CAM-Mythical Causes Scale (CAM-MYCS).18 19 The closed risk factor questions on the CAM assesses cancer risk perceptions of 11 established risk factors for cancer: smoking actively or passively, consuming alcohol, low levels of physical activity, consuming red or processed meat, getting sunburnt as a child, family history of cancer, human papillomavirus infection, being overweight, age ≥70 years, and low vegetable and fruit consumption. These items are causally associated with at least one cancer site and (except for non-modifiable risk factors) included in the European Code Against Cancer, an initiative of the European Commission to inform society of actions that can be undertaken to reduce the risk of cancer. The CAM-MYCS measure includes 12 questions on risk perceptions of mythical causes of cancer—non-established causes that are commonly believed to cause cancer without supporting scientific evidence. Accordingly, mythical causes are not classified as group 1 carcinogens (that is, carcinogenic to humans) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer and are not included in the European Code Against Cancer or the World Cancer Research Fund recommendations. These items include drinking from plastic bottles; eating food containing artificial sweeteners or additives and genetically modified food; the use of microwave ovens, aerosol containers, mobile phones, and cleaning products; living near power lines; feeling stressed; experiencing physical trauma; and being exposed to electromagnetic frequencies/non-ionising radiation, such as wi-fi networks, radio, and television. Responses to both measures are recorded on a five point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

To adapt the CAM and CAM-MYCS scales to the Spanish speaking population, we followed a methodological approach described in the guideline of Sousa et al: “Translation, adaptation, and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline.”20 In brief, two interpreters (one of whom was a specialist in cancer) translated the survey into Spanish. A third researcher resolved ambiguities and discrepancies through consensus. Two native translators (one of whom was a specialist in cancer) blindly back translated the consensus translated survey into English. We compared the two back translations and the original survey to evaluate the similarity among the instructions, items, and response format regarding wording and meaning. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus reached by the five translators involved, and we also obtained feedback from the developers of the original survey.

Finally, we asked the participants about other perceived cancer risks, using the statements “it seems like everything causes cancer,” “there’s not much you can do to lower your chances of getting cancer,” and “cancer worries me a lot,” and the question “compared with other people of your age, how likely are you to get cancer in your lifetime?” The possible responses were strongly disagree, disagree, unsure, agree, and strongly agree for the three statements and very likely, likely, neither unlikely nor likely, unlikely, and very unlikely for the question. We piloted the questionnaire (n=15) to test for any technical problems and estimate the time for completion.

Participants

We collected data from January to March 2022 and obtained 1754 responses. We identified that 14 responses had the same values for all 23 CAM items and therefore considered them to be low quality surveys and excluded them from analyses. We excluded partial responses to covid-19 vaccination and CAM items. Nine responses had missing information on covid-19 vaccination, and 232 participants filled only the first page of the survey so that information on cancer beliefs (CAM items) was missing. Five more participants did not respond to all the cancer belief items and were excluded from analyses. Conspiracy belief items were on the last page of the survey, and 57 participants did not complete this information. Considering that the participants had given information on cancer beliefs and covid-19 vaccination, we retained these data in analyses. We reclassified four responses on conspiracy questions as “not conspiracists,” as the participants reported in open comments that they believed in conspiracies “just for fun.” This yielded a final sample size of 1494 responses. Descriptive characteristics of full and partial responders are provided in supplementary table A.

Statistical analysis

We did basic descriptive analyses of the responses to the questions on sociodemographics, health behaviours, and conspiracy beliefs. We dichotomised CAM and CAM-MYCS responses into “correct” (strongly agree/agree on CAM, strongly disagree/disagree on CAM-MYCS) and “incorrect” (unsure/disagree/strongly disagree on CAM, unsure/agree/strongly agree on CAM-MYCS) responses, which resulted in a total score of 0-11 for CAM and 0-12 for CAM-MYCS (1 point for each correct answer). We also added the dichotomised “correct”’ CAM and CAM-MYCS responses together, resulting in a 0-23 CAM-total score. We converted the scores to a “percentage correct” (0-100) score, using the percentage of maximum possible method. We classified responses on whether screening was recommended for certain types of cancer as correct if they were marked “yes” for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancers, according to current recommendations by the European Code of Cancer, and incorrect if they were marked “yes” for lung, ovarian, and prostate cancers.

We did multivariable analyses of CAM, CAM-MYCS, and CAM-total by using quantile regression. We used unconditional logistic regression to do multivariable analyses of binary variables. We introduced missing values into the models as independent categories. We treated ordinal variables as continuous variables to test linear trends. Models were adjusted for covid-19 vaccination (unvaccinated versus one dose or more), conspiracy beliefs (yes, no), preference for medicine (alternative, conventional), age (<25, 25-34, 35-44, and ≥45 years), sex (male, female, and non-binary), education level (below college level, at least college level), region (Europe, others), medical occupation (no, yes), body mass index (body mass index <25, 25-29.9, and ≥30), regular alcohol intake (no, yes), smoking (never, ever), personal history of cancer (no, yes), and source of the survey (ForoCoches, cancer blog, 4Chan/Reddit/Hispachan/others). All tests were two tailed, with a significance level of 0.05. We used Stata version 16.0 for all analyses and generated graphs by using R version 4.1.2. We obtained consent to participate by using the following sentence: “I understand the purpose of this study, and I grant consent to the use of my responses for the purposes of this study (Yes/No).” In total, 46 participants explicitly denied their consent to participate by clicking “No.” We calculated the sample size by using the previous CAM-total of Shahab et al.21 Assuming a one to four ratio, we needed at least 290 (58:232) participants to detect a 15% two sided difference in the CAM-total score with 80% power and 650 (130:520) participants to detect a 10% difference between the two groups.

Sensitivity analyses

Given that 80% of the sample was collected from Spain, we did restricted analyses among respondents residing in Spain to weigh responses for the representative distribution of sex, age, and education, considering national data from the Spanish National Statistics Institute.22 In particular, we rebalanced responses from 1068 participants in ForoCoches who reported residence in Spain by age (18-34/35-59 years), sex (male/female), and education (below college level, at least college level). We used data from the Continuous Household Survey (2020), which represents more than 99% of the total population residing in Spain, to obtain the proportion of each of the six groups of our demographic profile in the target population.22 We obtained the weights by dividing the proportion of the group in the target population by the proportion of the group in the survey population. Next, we did analyses similar to those described above using weighted data.

Patient and public involvement

An anonymous person who professed reptilian conspiracy theory helped to design the questionnaire. We maintained interesting chats in forums with other people who held conspiracy beliefs and who provided useful insights. The survey also contained an open response option for general comments. We did no formal qualitative analysis as it was beyond the scope of the project but selected 11 responses for illustrative purposes (table 1).

Table 1.

Selected free text responses from websites and open responses

| Source | Comment |

|---|---|

| 4Chan | It’s really about the shapeshifting lizards, isn’t it |

| 4Chan | You might want to post this on reddit for a more realistic sample, you are going to get a LOT of antivaxx schizos posting here |

| 4Chan | I’d only know if I got a plane and chased the sun, anything else is something somebody told me. Agnostic earthers rise! |

| This is hilarious. Why did you ask about flat earth | |

| ForoCoches | This survey gives cancer* |

| ForoCoches | Well, according to many “experts,” EVERYTHING causes cancer. We can't even breathe* |

| ForoCoches | Being born between June 21 - July 22. If not, you are from another (horoscope) sign. I hope I helped you* |

| Survey (open question) | Stupid questions. no one can prove the earth is round or flat and or that lizard people do or do not exist. anyone who says it’s definitely either way is stupid |

| Survey (open question) | I am a reptilian experiencer. I believe in reptilians because I have seen them, not because I heard somebody else believes in them |

| Survey (open question) | Everyone knows that the Bellatricians died out eons ago, and Pleiadians are those among us, and they are much more dangerous* |

| Survey (open question) | I believe in lots of reptilians and them being capable of appearing human, but I don’t think they are many presidents. They are in other positions |

Translated from Spanish.

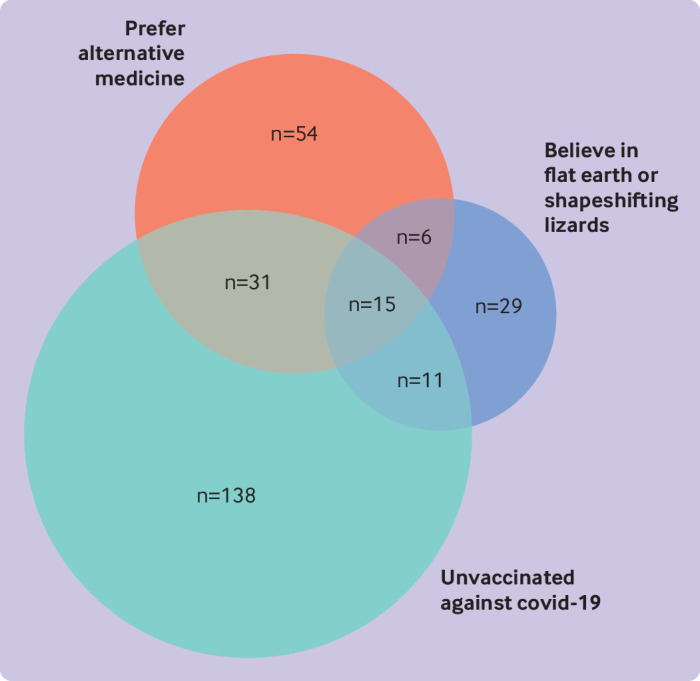

Results

Characteristics of the sample are listed in table 2 and supplementary table A. Full responders were more likely to be aged 25-44 years, come from Europe, have a higher education level, and originate from ForoCoches (supplementary table A) than the partial responders. Among the full responders, 209 (14.0%) did not receive any covid-19 vaccination and 62 (4.1%) reported that they believed that the Earth was flat or that shapeshifting lizards existed (table 2). Additionally, 112 (7.5%) participants reported that they preferred alternative medicine to conventional medicine. Figure 1 shows a Venn diagram in which 15 responders were simultaneously classified as unvaccinated against covid-19, believed in conspiracies, and preferred alternative medicine.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics by health preferences and conspiracy beliefs. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Covid-19 vaccination | Believes in flat earth or shapeshifting lizards | Preferred type of medicine | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One dose or more (n=1285) | Unvaccinated (n=209) | P value* | No (n=1375) | Yes (n=62) | P value* | Conventional (n=1367) | Alternative (n=112) | P value* | |||

| Age, years: | 0.78 | 0.21 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| <25 | 210 (16.3) | 33 (16) | 222 (16.1) | 14 (23) | 230 (16.8) | 10 (9) | |||||

| 25-34 | 559 (43.5) | 98 (47) | 601 (43.7) | 30 (48) | 599 (43.8) | 53 (47) | |||||

| 35-44 | 351 (27.3) | 51 (24) | 373 (27.1) | 10 (16) | 369 (27.0) | 27 (24) | |||||

| ≥45 | 165 (12.8) | 27 (13) | 179 (13.0) | 8 (13) | 169 (12.4) | 22 (20) | |||||

| Sex: | 0.64 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Female | 222 (17.3) | 41 (20) | 236 (17.2) | 16 (26) | 227 (16.6) | 34 (30) | |||||

| Male | 1035 (80.5) | 163 (78) | 1114 (81.0) | 39 (63) | 1113 (81.4) | 73 (65) | |||||

| Non-binary | 17 (1.3) | 2 (1) | 12 (0.9) | 7 (11) | 15 (1.1) | 4 (4) | |||||

| Region: | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Europe | 1144 (89.0) | 167 (80) | 1222 (88.9) | 39 (63) | 1220 (89.2) | 77 (69) | |||||

| South America | 61 (4.7) | 12 (6) | 65 (4.7) | 6 (10) | 61 (4.5) | 11 (10) | |||||

| North America | 63 (4.9) | 20 (10) | 72 (5.2) | 9 (15) | 63 (4.6) | 20 (189) | |||||

| Asia and Oceania | 9 (0.7) | 6 (1) | 12 (0.9) | 3 (5) | 13 (1.0) | 2 (2) | |||||

| Africa | 1 (0.1) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (1) | |||||

| Education: | 0.006 | 0.09 | 0.18 | ||||||||

| Below college level | 558 (43.4) | 112 (54) | 603 (43.9) | 34 (55) | 604 (44.2) | 57 (51) | |||||

| At least college level | 722 (56.2) | 96 (46) | 766 (55.7) | 28 (45) | 757 (55.4) | 55 (49) | |||||

| Medical occupation: | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.22 | ||||||||

| No | 1101 (85.7) | 188 (90) | 1192 (86.7) | 48 (77) | 1184 (86.6) | 91 (81) | |||||

| Yes | 169 (13.2) | 17 (8) | 167 (12.1) | 12 (19) | 168 (12.3) | 18 (16) | |||||

| Body mass index: | 0.32 | 0.60 | 0.81 | ||||||||

| <25 | 693 (53.9) | 121 (58) | 773 (56.2) | 35 (56) | 744 (54.4) | 60 (54) | |||||

| 25-29.9 | 391 (30.4) | 58 (28) | 430 (31.3) | 17 (27) | 408 (29.8) | 37 (33) | |||||

| ≥30 | 141 (11.0) | 17 (8) | 149 (10.8) | 9 (15) | 147 (10.8) | 11 (10) | |||||

| Alcohol consumption: | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.57 | ||||||||

| No | 855 (66.5) | 148 (71) | 957 (69.6) | 39 (63) | 917 (67.1) | 78 (70) | |||||

| Yes | 381 (29.6) | 55 (26) | 412 (30.0) | 23 (37) | 400 (29.3) | 30 (27) | |||||

| Smoking: | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.41 | ||||||||

| Never | 769 (59.8) | 126 (60) | 853 (62.0) | 35 (56) | 826 (60.4) | 61 (54) | |||||

| Ever | 457 (35.6) | 70 (33) | 500 (36.4) | 26 (42) | 479 (35.0) | 42 (38) | |||||

| Personal history of cancer: | 0.46 | 0.004 | 0.12 | ||||||||

| No | 1211 (94.2) | 195 (93) | 1307 (95.1) | 53 (85) | 1290 (94.4) | 101 (90) | |||||

| Yes | 53 (4.1) | 11 (5) | 54 (3.9) | 7 (11) | 56 (4.1) | 8 (7) | |||||

| Source: | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Cancer blog | 60 (4.7) | 2 (1) | 56 (4.1) | 4 (6) | 48 (3.5) | 14 (13) | |||||

| Hispachan, 4Chan, Reddit, and others | 200 (15.6) | 63 (30) | 222 (16.1) | 30 (48) | 222 (16.2) | 39 (35) | |||||

| ForoCoches | 1025 (79.8) | 144 (69) | 1097 (79.8) | 28 (45) | 1097 (80.2) | 59 (53) | |||||

χ2, calculated without missing values.

Numbers do not add up to total because of missing values.

Fig 1.

Venn diagram for covid-19 vaccination, medicine preferences, and conspiracy beliefs. Values were missing from 15 responders for medicine preferences and 57 for conspiracy beliefs; one missing value was common to both variables

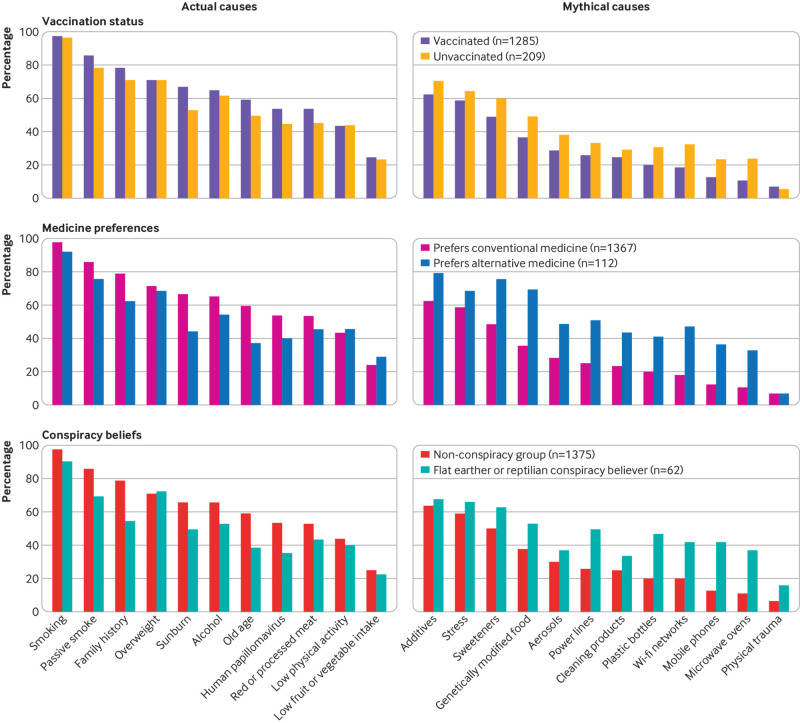

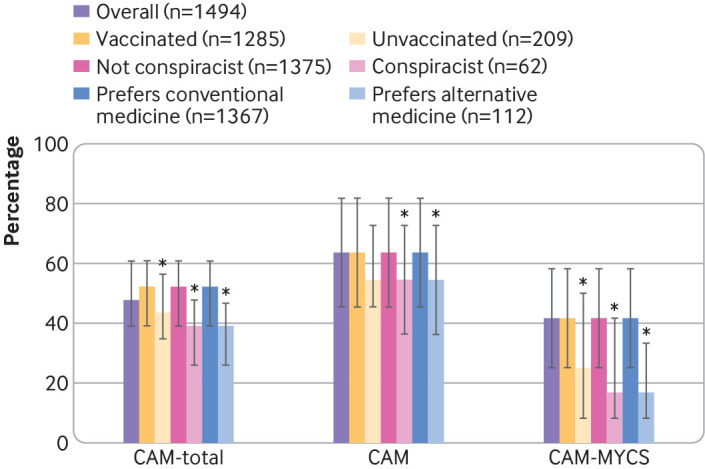

Among all participants, awareness of the actual causes of cancer (median CAM score 63.6%, interquartile range 45.5-81.8%) was greater than awareness of the mythical causes of cancer (41.7%, 16.7-58.3%) (fig 2 and fig 3). Overall, the most endorsed actual causes of cancer were active smoking (97.4%; n=1455), passive smoking (85.1%; n=1271), family history of cancer (77.6%; n=1160), and being overweight (71.4%; n=1066). By contrast, less than 25% (n=369) of the participants correctly identified low intake of fruits and vegetables as a cause of cancer. The most endorsed mythical causes of cancer were eating food containing additives (63.9%; n=954) or sweeteners (50.7%; n=758), feeling stressed (59.7%; n=892), and eating genetically modified foods (38.4%; n=573) (supplementary figure A).

Fig 2.

Cancer awareness measures by conspiracy beliefs and health characteristics. Bars represent median of percentage of correct responses for 11 Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM), 12 CAM-Mythical Causes Scale (CAM-MYCS), and 23 aggregated (CAM-total) items. Interval lines correspond to interquartile ranges. Models were adjusted for covid-19 vaccination, conspiracy beliefs, preferences for type of medicine, age, sex, education level, region, medical occupation, body mass index, alcohol intake, smoking, past history of cancer, and source of survey. *Category associated with independent variable (CAM-total, CAM, or CAM-MYCS), compared with their counterparts (vaccinated against covid-19, no conspiracy beliefs, or preferred conventional medicine) in multivariable regression analyses (P<0.05)

Fig 3.

Endorsement of actual and mythical causes of cancer by covid-19 vaccination, conspiracy beliefs, and medicine preferences

Awareness of the actual and mythical causes of cancer in the unvaccinated and conspiracy groups (those who believed that the Earth was flat or that shapeshifting lizards existed) was lower than in their counterparts. Specifically, the unvaccinated and conspiracy groups accurately identified a median of 54.5% (45.5-72.7%) and 54.5% (36.4-72.7%) of the actual causes, respectively; by contrast, the respective counterparts identified a median of 63.6% (45.5-81.8%) and 63.6% (45.5-81.8%) of the actual causes of cancer (P=0.13 and P=0.003 in adjusted models, respectively). Moreover, a median of 25.0% (8.3-50.0%) and 16.7% (8.3-41.7%) of the mythical causes were correctly identified in the unvaccinated and conspiracy groups; by contrast, 41.7% (16.7-58.3%) and 41.7% (16.7-58.3%) of the mythical causes were correctly identified by their counterparts (P<0.001 in adjusted models for both comparisons) (fig 3). The preference for alternative medicine was also associated with lower CAM and CAM-MYCS scores. Specifically, a median of 63.6% (45.5-81.8%) of the actual causes were accurately identified among those who preferred conventional medicine or were unsure; by contrast, 54.5% (36.4-72.7%) of the actual causes were identified among those who preferred alternative medicine (adjusted P=0.04). Furthermore, 41.7% (16.7-58.3%) and 16.7% (8.3-33.3%) of mythical causes were identified by those who preferred conventional and alternative medicine, respectively (adjusted P<0.001) (fig 3). Male sex, higher education, and medical occupation survey profile were positively associated with higher CAM-total, CAM, and/or CAM-MYCS scores (supplementary table B). Generally, a risk factor for cancer was inversely associated with the endorsement of that specific risk factor as a cause of cancer. For instance, we observed an inverse trend between age and the belief that being >70 years old was a risk factor for cancer (supplementary table C). We observed similar patterns for obesity, passive smoking, and alcohol consumption.

Overall, 673 (45.0%) participants agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “It seems like everything causes cancer.” We observed no significant differences according to vaccination status (44% (n=92) among the unvaccinated; adjusted P=0.96), conspiracy group (42% (n=26); adjusted P=0.91), or alternative medicine preference (36% (n=40); adjusted P=0.15) compared with their counterparts (45.2% (n=581); 45.7% (n=628); and 45.8% (n=626), respectively) (table 3). This belief was significantly associated with alcohol consumption (P<0.001) and was inversely associated with age (adjusted P for trend <0.001) and male sex (P<0.001) (supplementary table D). Overall, 305 (20.4%) participants agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “There’s not much I can do to reduce the chances of getting cancer” (data not shown). Of the participants, 86.9% (95% confidence interval 85.1% to 88.6%; n=1256) accurately identified that screening programmes are established in the general population for the detection of breast cancer, 69.3% (66.9% to 71.7%; n=1002) did so for colorectal cancer, and 50.0% (47.4% to 52.6%; n=723) for cervical cancer. In addition, 73.6% (71.2% to 75.8%; n=1063) of participants accurately identified that screening programmes are not established in the general population for lung cancer, 66.0% (63.5% to 68.5%; n=954) did so for ovarian cancer, and 27.9% (25.6% to 30.3%; n=403) for prostate cancer (supplementary table E). We observed no significant differences according to vaccination status, conspiracy group, or type of medicine preference, except for a lower awareness of the available colorectal screening programmes in the conspiracy group (51.6%, 38.6% to 64.5%; n=32; adjusted P=0.05, compared with the non-conspiracy group).

Table 3.

Agreement with statement “It seems like everything causes cancer” by sociodemographic factors, conspiracy beliefs, and health characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Group | Strongly disagree, disagree, or not sure | Agree or strongly agree | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 821 (55.0) | 673 (45.0) | ||

| Covid-19 vaccination: | 0.96 | |||

| One dose or more | 704 (54.8) | 581 (45.2) | Reference | |

| Unvaccinated | 117 (56) | 92 (44) | 1.01 (0.73 to 1.39) | |

| Believes in flat earth or shapeshifting lizards: | 0.91 | |||

| No | 747 (54.3) | 628 (45.7) | Reference | |

| Yes | 36 (58) | 26 (42) | 0.97 (0.55 to 1.71) | |

| Preferences on type of medicine: | 0.15 | |||

| Conventional or unsure | 741 (54.2) | 626 (45.8) | Reference | |

| Alternative | 72 (64) | 40 (36) | 0.72 (0.46 to 1.13) |

CI=confidence interval.

Models were adjusted for covid-19 vaccination, conspiracy beliefs, preferences for type of medicine, age, sex, education level, region, medical occupation, body mass index, alcohol intake, smoking, past history of cancer, and source of survey.

Sensitivity analyses in Spanish respondents weighting for sex, age, and education using data from the Spanish National Statistics Institute yielded similar results for awareness of actual causes of cancer (median CAM score 63.6%, interquartile range 45.5-81.8%) but lower estimates of mythical cancer causes (33.3%, 8.3-50.0%) than in the non-weighted analyses (supplementary table F). Weighted sensitivity analyses did not yield significant associations, except for a lower median CAM score among conspiracy believers (45.5%, 45.5-72.7%) than among non-believers (63.6%, 45.5-81.8).

Discussion

Almost half of the participants agreed with the statement “It seems like everything causes cancer.” This highlights the difficulty that society encounters in distinguishing the actual causes of cancer from mythical causes owing to the mass information on the news and social media platforms. Overall, awareness of the actual and mythical causes of cancer was low. Only a median of approximately two thirds of the actual causes of cancer and approximately 40% of the mythical causes were correctly identified. We provided first time data on beliefs about a range of actual and mythical causes of cancer according to conspiracy beliefs and health preferences. In adjusted models, people who believed in conspiracies, rejected the covid-19 vaccine, or preferred alternative medicine were more likely to endorse mythical causes of cancer than their counterparts but were less likely to endorse actual causes of cancer.

We evaluated beliefs about cancer among flat earthers and reptilian conspiracy theorists, although associations with other existing conspiracies could be shown in future studies. Beliefs about cancer may differ substantially among chemtrail believers, global warming deniers, those who believe that the moon landings were staged by NASA in a film studio, those who peddle the “Santa is an Illuminati weapon” conspiracy, or even those who believe that birds are drones operated by the United States government to spy on citizens.23 24 The sample in this study may not represent the general population; however, the administration of at least one dose of the covid-19 vaccine (87.3% in the Spanish sample) is comparable to population estimates (88.0%).25 We could not estimate whether the prevalence of flat earthers or reptilian conspiracy believers in our sample is comparable to that in the Spanish population because, to our knowledge, no estimates are available for comparison. Assuming that a lower knowledge of risk factors for cancer is associated with non-response because of a social desirability bias, this would result in lower CAM scores in the general population than in our sample, which reinforces our conclusion that awareness of the actual and mythical causes of cancer was poor.

Comparison with previous studies

A cognitive paradox has been observed among people who reject covid-19 vaccines—they generally believe less in a wide range of well established facts and more in fake statements than do vaccine supporters26; this is consistent with our results. Our results on the overall endorsement of causes of cancer are mostly in agreement with the previous literature (supplementary figure A).21 27 28 29 30 Awareness of physical inactivity, human papillomavirus infection, and poor diet as risk factors for cancer is reported to be low.21 27 28 29 However, our estimates were lower for certain items, such as sunburn and low intake of fruits and vegetables, than for the CAM benchmark data.30 In line with our results, the most endorsed mythical causes of cancer in a representative English population were exposure to stress and food additives.21

Digital misinformation is abundant on the internet. False information spreads further and deeper than true information.31 32 Social media algorithms promote the use of a similar language that facilitates the aggregation of users. This results in many people believing in ideas, including conspiracies, that are clearly against the current scientific knowledge. Non-experts tend to justify the rejection of scientific evidence by questioning the motivation of experts and therefore resolving any cognitive dissonance.33 Conspiracists and people with a preference for alternative medicine may share a similar magical world view. Interestingly, those who preferred alternative medicine were more prone to endorse mythical causes of cancer than were the rest of the participants. In patients with cancer, the fear of death and serious side effects from standard treatments may drive people to seek alternative treatments, which can become a source of hope and empowerment but are associated with increased mortality.34 Thus, these patients are especially vulnerable to misinformation that could lead to delays in treatment, the toxicity of alternative therapies, or adverse interactions with standard care.6

Some organisations have taken initial steps to reduce the increasing amount of misinformation on healthcare. Examples include fact checking approaches, such as the website Rumor Control by the US Food and Drug Administration,35 and “inoculation” approaches that include tutorials informing people of fake news to help them to make better choices about what to share online.36 Additionally, interventions to rate or reflect the accuracy of online content are effective in distinguishing between true and false content.36 Crowd sourced accuracy ratings are proposed to improve online ranking algorithms.36 Accordingly, the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine proposed new communication strategies, including the reconfiguration of platform features that promote misinformation.37 They also proposed partnering with trusted social media, cultivating scientific literacy, and monitoring content that spreads misinformation.37 Other authors have suggested that persuasive messages reflecting different world views of the population (tailored health communication) could be more effective than fact based campaigns.13 38

Strengths and limitations of study

This study is the first to show the possible patterns of beliefs about cancer among conspiracy believers. Our sample size was relatively large but limited among conspiracy groups because we obtained a reduced number of responses from certain platforms. Particularly, we had low “karma” on Reddit, which limited the distribution of our survey, and we were banned from several platforms (including 4Chan), which highlighted the perceptions of institutional organisations as untrustworthy. The main limitation is that we used an anonymous online cross sectional survey, which may be associated with response and sampling biases. We had conversations with an individual who believed in the reptilian conspiracy and learnt about the presence of potentially paranoid features in this group: they may feel spied on by reptilians and would never answer the survey if it was not completely anonymous. This background knowledge implied the unfeasibility of sampling using telephone numbers and/or postal addresses; thus, we used a non-probability sampling approach wherein response rates and potential duplicate responses could not be evaluated. Representative probability sampling is effective, but it incurs considerable monetary, personal, and time costs. Additionally, its benefits have diminished owing to the decline in response rates over the years, and random digit dialling sampling is less feasible for young adults because of its low response rate.39 By contrast, non-probability sampling may be more prone to bias, although it is more feasible and cost effective. This bias can be controlled by weighting and statistical adjustments.40 We applied a weighting approach to the Spanish population, which showed mostly similar results and was significant for the association between CAM estimates and conspiracy beliefs, supporting our conclusions. Other observational designs, such as case-control or cohort studies, were not relevant to our research question and may also be subject to selection and response bias when the response is associated with the outcome of interest.41 42

Risk factors classified as mythical or non-established on the basis of current evidence may be reclassified in future as established risk factors, as the evaluation of causes of cancer is a dynamic process and will progress as new evidence becomes available. Our responses to conspiracy beliefs may be affected by “troll” or fake responses. Responses among those who preferred alternative medicine rather than conventional medicine were less prone to this misclassification bias by fake responses. This group endorsed mythical cancer causes the most and the actual causes the least. Another internationally validated instrument in English was developed to measure awareness and beliefs about cancer (ABC measure)43; however, no internationally validated instrument exists for mythical causes. Therefore, we used the CAM and CAM-MYCS measures, previously validated in the UK, which have a similar structure (with five possible responses rather than the four option ABC measure).18 19 Owing to the online administration of the survey, only people with internet access could respond to it, which raises the possibility of selection bias. However, in 2021, an estimated 94% of the Spanish population used the internet within the previous three months,44 so we expected a low impact of this bias.

A strategic multidisciplinary research agenda to evaluate the effect of misinformation on health is crucial. Different methods will be needed to answer the questions raised while creating this roadmap. For instance, interviewing one conspiracy believer gave relevant insights; formal qualitative studies may offer further information that can help to define enrolment strategies and increase participation rates. Innovative designs using alternative methods (using social media or even gaming platforms45) could help to approach a larger potentially misinformed audience and, combined with conventional designs, understand the burden of misinformation. Furthermore, a detailed characterisation of the wide range of non-scientific beliefs, ideally using existing scales on conspiracy and magical beliefs,46 47 48 49 50 will help to increase understanding of the effect of the different participant profiles on health.

Conclusion and implications

We evaluated the patterns of beliefs about cancer among people who believed in conspiracies, rejected the covid-19 vaccine, or preferred alternative medicine. We observed that the participants who belonged to these groups were more likely to endorse mythical causes of cancer than were their counterparts but were less likely to endorse the actual causes of cancer. Almost half of the participants, whether conspiracists or not, agreed with the statement “It seems like everything causes cancer,” which highlights the difficulty that society encounters in differentiating actual causes of cancer from mythical causes owing to mass (veridical or not) information. This suggests a direct connection between digital misinformation and consequent potential erroneous health decisions, which may represent a further preventable fraction of cancer. Cultivating oriented medical education and scientific literacy, improving online ranking algorithms, building trust, and using effective health communication and social marketing campaigns may be possible ways to tackle this complex public health threat.

What is already known on this topic

Knowing the established risk factors for cancer is the first step in ensuring adherence to cancer prevention recommendations

Difficulties in differentiating the actual causes of cancer from mythical causes are caused by mass information, some of which is not based on scientific results

No data exist on vaccination scepticism or conspiracy beliefs—for example, reptilians or flat earth—in relation to beliefs about and attitudes to cancer prevention

What this study adds

Awareness of causes of cancer was poor, especially among people who rejected the covid-19 vaccine, preferred alternative medicine, or endorsed flat earth or reptilian conspiracies

This suggests a direct connection between digital misinformation and consequent potential erroneous health decisions, which may represent a further preventable fraction of cancer

Acknowledgments

We thank Edu Martin-Prieto, Eric Duell, Jordi Edo, Javi Sanz, Manu Jiménez, Emilio López, Aline Bosle, Javier Aparicio, Christopher Ray Thompson, Marisa Mena, Nati Patón, Beatriz Pelegrina, and Sonya Farrell for their invaluable contributions. We also thank all participants for participating in the survey. We are deeply grateful to the anonymous individual who believed in the reptilian conspiracy theory for helping to design the survey. Through interactions, we could better understand the suffering that misinformation is causing to cancer patients, conspiracy believers, and the entire society.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Online survey

Web appendix: Supplementary materials

Contributors: LC conceived the study. All the authors participated in designing the study and interpreting the data. All the authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. LC and SP did the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LC and YB analysed the data. LC is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: No external funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; LC has received speakers’ honorariums from Roche outside this work; PPT has received honorariums from Werfen outside this work; IDIBELL has signed a contract with Roche to collaborate in the development of the bioinformatics pipeline of a research project to detect endometrial cancer; the Cancer Epidemiology Research Program, to which SP, YB, AM, MB, RI, PPT, BS, LA, and LC are affiliated, has received unrestricted grants from Merck Sharp and Dohme, human papillomavirus test kits free of charge from Roche, reagents from Integrated DNA Technologies and Roche Diagnostics at a 50% discount, and Colli-Pee devices from Novosanis free of charge for research purposes; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; no important aspects of the study have been omitted; any discrepancies from the study as originally planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The authors will prepare a post for the blog https://mejorsincancer.org/ summarising the results of the study. This post will be further distributed in the forums in which participants were invited, including ForoCoches, Reddit, and others. The institutions to which the authors are affiliated (Catalan Institute of Oncology and IDIBELL) will prepare a press release to be distributed to journalists.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Bellvitge University Hospital (reference PR294/21). All research participants gave written informed consent.

Data availability statement

Data are available from the corresponding author (lcostas@iconcologia.net) on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209-49. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wild C, Weiderpass E, Stewart B, eds. World Cancer Report: Cancer research for cancer prevention. World Health Organization, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Code Against Cancer. 12 ways to reduce your cancer risk. https://cancer-code-europe.iarc.fr/index.php/en/.

- 4.World Cancer Research Fund International. Cancer Prevention Recommendations. https://www.wcrf.org/diet-and-cancer/cancer-prevention-recommendations/.

- 5. Cunningham SA, Yu R, Shih T, et al. Cancer-related risk perceptions and beliefs in Texas: findings from a 2018 population-level survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019;28:486-94. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teplinsky E, Ponce SB, Drake EK, et al. Collaboration for Outcomes using Social Media in Oncology (COSMO) . Online medical misinformation in cancer: distinguishing fact from fiction. JCO Oncol Pract 2022;18:584-9. 10.1200/OP.21.00764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swire-Thompson B, Lazer D. Public health and online misinformation: challenges and recommendations. Annu Rev Public Health 2020;41:433-51. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Golbeck J. Social media and shared reality Off the Edge: flat earthers, conspiracy culture, and why people will believe anything Kelly Weill Algonquin Books, 2022. 256 pp. Science 2022;375:624. 10.1126/science.abn6017 35143315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bessi A, Coletto M, Davidescu GA, Scala A, Caldarelli G, Quattrociocchi W. Science vs conspiracy: collective narratives in the age of misinformation. PLoS One 2015;10:e0118093. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dery M. The Vast Santanic Conspiracy. In: I must not think bad thoughts: drive-by essays on American dread, American dreams. University of Minnesota Press, 2012. 10.5749/minnesota/9780816677733.003.0024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bierwiaczonek K, Gundersen AB, Kunst JR. The role of conspiracy beliefs for COVID-19 health responses: A meta-analysis. Curr Opin Psychol 2022;46:101346. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lantian A, Muller D, Nurra C, et al. Stigmatized beliefs: Conspiracy theories, anticipated negative evaluation of the self, and fear of social exclusion. Eur J Soc Psychol 2018;48:939-54 10.1002/ejsp.2498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bryden GM, Browne M, Rockloff M, Unsworth C. Anti-vaccination and pro-CAM attitudes both reflect magical beliefs about health. Vaccine 2018;36:1227-34. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miro CJ, Toff B. How right-wing populists engage with cross-cutting news on online message boards: the case of ForoCoches and Vox in Spain. Int J Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Willem C, Tortajada I. Gender, voice and online space: expressions of feminism on social media in Spain. Media Commun 2021;9:62-71 10.17645/mac.v9i2.3851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. REDCap Consortium . The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377-81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stubbings S, Robb K, Waller J, et al. Development of a measurement tool to assess public awareness of cancer. Br J Cancer 2009;101(Suppl 2):S13-7. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith SG, Beard E, McGowan JA, et al. Development of a tool to assess beliefs about mythical causes of cancer: the Cancer Awareness Measure Mythical Causes Scale. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022825. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:268-74. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shahab L, McGowan JA, Waller J, Smith SG. Prevalence of beliefs about actual and mythical causes of cancer and their association with socio-demographic and health-related characteristics: Findings from a cross-sectional survey in England. Eur J Cancer 2018;103:308-16. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Informes Metodológicos Estandarizados. https://www.ine.es/dynt3/metadatos/es/RespuestaDatos.html?oe=30274.

- 23.Wikipedia. List of conspiracy theories. 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_conspiracy_theories&oldid=1086918863.

- 24.Lorenz T. Birds aren’t real, or are they? Inside a gen z conspiracy theory. 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/09/technology/birds-arent-real-gen-z-misinformation.html.

- 25.COVID19 Vaccine Tracker. Vaccination Rates, Approvals & Trials by Country. 2022. https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/trials-vaccines-by-country/.

- 26. Newman D, Lewandowsky S, Mayo R. Believing in nothing and believing in everything: The underlying cognitive paradox of anti-COVID-19 vaccine attitudes. Pers Individ Dif 2022;189:111522. 10.1016/j.paid.2022.111522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lagerlund M, Hvidberg L, Hajdarevic S, et al. Awareness of risk factors for cancer: a comparative study of Sweden and Denmark. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1156. 10.1186/s12889-015-2512-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hvidberg L, Pedersen AF, Wulff CN, Vedsted P. Cancer awareness and socio-economic position: results from a population-based study in Denmark. BMC Cancer 2014;14:581. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sanderson SC, Waller J, Jarvis MJ, Humphries SE, Wardle J. Awareness of lifestyle risk factors for cancer and heart disease among adults in the UK. Patient Educ Couns 2009;74:221-7. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Connor K, Hudson B, Power E. Awareness of the signs, symptoms, and risk factors of cancer and the barriers to seeking help in the UK: comparison of survey data collected online and face-to-face. JMIR Cancer 2020;6:e14539. 10.2196/14539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Del Vicario M, Bessi A, Zollo F, et al. The spreading of misinformation online. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:554-9. 10.1073/pnas.1517441113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018;359:1146-51. 10.1126/science.aap9559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Landrum AR, Olshansky A. The role of conspiracy mentality in denial of science and susceptibility to viral deception about science. Politics Life Sci 2019;38:193-209. 10.1017/pls.2019.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Johnson SB, Park HS, Gross CP, Yu JB. Use of alternative medicine for cancer and its impact on survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110. 10.1093/jnci/djx145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Food and Drug Administration. Rumor control. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/rumor-control.

- 36. Pennycook G, Rand DG. The psychology of fake news. Trends Cogn Sci 2021;25:388-402. 10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Health and Medicine Division. Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. Roundtable on Health Literacy . Addressing Health Misinformation with Health Literacy Strategies: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. National Academies Press, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lutkenhaus RO, Jansz J, Bouman MP. Tailoring in the digital era: Stimulating dialogues on health topics in collaboration with social media influencers. Digit Health 2019;5:2055207618821521. 10.1177/2055207618821521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gundersen DA, Wivagg J, Young WJ, Yan T, Delnevo CD. The use of multimode data collection in random digit dialing cell phone surveys for young adults: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e31545. 10.2196/31545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Valliant R, Dever JA. Survey weights: a step-by-step guide to calculation. Stata Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pizzi C, De Stavola BL, Pearce N, et al. Selection bias and patterns of confounding in cohort studies: the case of the NINFEA web-based birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:976-81. 10.1136/jech-2011-200065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology 2004;15:615-25. 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Simon AE, Forbes LJL, Boniface D, et al. ICBP Module 2 Working Group, ICBP Programme Board and Academic Reference Group . An international measure of awareness and beliefs about cancer: development and testing of the ABC. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001758. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta sobre equipamiento y uso de tecnologías de información y comunicación en los hogares: Últimos datos. 2022. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176741&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976608.

- 45. Wang W, Rothschild D, Goel S, et al. Forecasting elections with non-representative polls. Int J Forecast 2015;31:980-91 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2014.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lindeman M, Keskivaara P, Roschier M. Assessment of magical beliefs about food and health. J Health Psychol 2000;5:195-209. 10.1177/135910530000500210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hyland ME, Lewith GT, Westoby C. Developing a measure of attitudes: the holistic complementary and alternative medicine questionnaire. Complement Ther Med 2003;11:33-8. 10.1016/S0965-2299(02)00113-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brotherton R, French CC, Pickering AD. Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: the generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Front Psychol 2013;4:279. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bruder M, Haffke P, Neave N, Nouripanah N, Imhoff R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Front Psychol 2013;4:225. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Drinkwater KG, Dagnall N, Denovan A, Neave N. Psychometric assessment of the Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230365. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Online survey

Web appendix: Supplementary materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author (lcostas@iconcologia.net) on reasonable request.