Abstract

The intrinsic mechanisms sensing the imbalance of energy in cells are pivotal for cell survival under various environmental insults. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) serves as a central guardian maintaining energy homeostasis by orchestrating diverse cellular processes, such as lipogenesis, glycolysis, TCA cycle, cell cycle progression and mitochondrial dynamics. Given that AMPK plays an essential role in the maintenance of energy balance and metabolism, managing AMPK activation is considered as a promising strategy for the treatment of metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and obesity. Since AMPK has been attributed to aberrant activation of metabolic pathways, mitochondrial dynamics and functions, and epigenetic regulation, which are hallmarks of cancer, targeting AMPK may open up a new avenue for cancer therapies. Although AMPK is previously thought to be involved in tumor suppression, several recent studies have unraveled its tumor promoting activity. The double-edged sword characteristics for AMPK as a tumor suppressor or an oncogene are determined by distinct cellular contexts. In this review, we will summarize recent progress in dissecting the upstream regulators and downstream effectors for AMPK, discuss the distinct roles of AMPK in cancer regulation and finally offer potential strategies with AMPK targeting in cancer therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Energy balance is important for maintaining cell survival and body homeostasis. Imbalance of energy metabolism accompanied by obesity often results in the development of cancers, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and kidney disease. In order to cope with diverse stresses leading to energy imbalance, cells need to develop protective mechanisms for maintaining energy homeostasis and cell survival. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a well-known energy sensor that is activated to regulate diverse signals and metabolic pathways in response to various stimuli including caloric restriction [1], exercise [2], aging [3–5] and obesity [6], thereby sustaining energy homeostasis and serving as the guardian of metabolism.

As key energy molecules, adenine nucleotide ATPs are constantly generated to meet cell energy demands through diverse metabolic pathways. As an energy sensor, AMPK senses the increased ratio of AMP/ATP or ADP/ATP and is activated by upstream kinases such as liver kinase B1 (LKB1) [7–9] and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2 (CaMKK2 or CaMKKβ) [10–12]. As a consequence, AMPK turns on the catabolic processes such as glycolysis [13, 14], TCA cycle [15] and fatty acid oxidation [16, 17] to produce energy, but shuts off the anabolic metabolism including fatty acid synthesis, protein synthesis and steroid synthesis to limit energy usage by inactivating mTORC1 [18], thus maintaining the energy homeostasis.

Post-translational modification of AMPK has been demonstrated to play an important role in the stability of AMPK complexes and also directly impact on the AMPK enzymatic activity. Phosphorylation of AMPK on Threonine 172 (T172) residue dramatically increases AMPK activity [19, 20] to further phosphorylate its downstream substrates, thus governing various biological functions such as cellular metabolism, mitochondrial dynamics, Golgi assembly, gene transcription and cell cycle progression. ACC phosphorylation by AMPK leads to the inhibition of lipogenesis [16, 17]. MFF (mitochondrial fission factor) and ULK1 (unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1) phosphorylation by AMPK induces mitochondrial fission and mitophagy respectively [21–23]. Either inhibition of fatty acid synthesis or promotion of mitochondrial dynamics through AMPK activation eventually facilitates cellular adaptation to metabolic stress. Thereby, understanding how AMPK is activated as well as the downstream signals AMPK regulates will yield useful strategies to develop small molecules for targeting AMPK signals in the treatment of metabolic diseases or cancer.

For the past two decades, many small molecules have been developed for AMPK targeting. Metformin [24] and salicylate [25], widely used drugs for type 2 diabetes treatment, could indirectly activate AMPK, leading to the increase of glucose uptake. Additionally, several herbal medicines such as berberine [26–28] and resveratrol [27] have been shown to indirectly activate AMPK via the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. Importantly, some compounds have been identified to activate AMPK by directly associating with its α, β or γ subunits, which in turn causes the allosteric conformational alteration of AMPK complex. Recently, sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (canagliflozin) [29, 30], PF-739 [31], PF-06409577 [32] and PAN-AMPK activator (MK-8722) [33] have emerged preclinical and clinical efficacy of reducing blood glucose similar to metformin and phenformin. Accumulated studies have shown that pharmacological activation of AMPK by several small molecules is useful for the treatment of metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, although pharmacological targeting AMPK for cancer treatment still remains controversial in different cancer types.

In this review, we will describe the upstream regulation and downstream substrates of AMPK under physiological stresses. Moreover, we will elaborate the biological functions of AMPK in various cellular compartments including mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, ER (endoplasmic reticulum) and nucleus [34]. Finally, we will discuss the distinct roles of AMPK in cancer regulation and its targeting strategies by small molecules for cancer therapy in preclinical models.

AMPK COMPLEX

AMPK forms a heterotrimeric complex, which is composed of catalytic α subunits and regulatory β and γ subunits. There are multiple genes encoding each subunit, generating two α (α1, α2), two β (β1, β2) and three γ subunits (γ1, γ2, γ3). Thus, AMPK heterotrimers can form up to 12 αβγ combinations which display slightly different subcellular or tissue-specific distribution [35]. For instance, isoforms with catalytic α1 and regulatory β2 are predominantly expressed in human liver [36], while isoforms with γ2 subunit are highly expressed in human heart [36]. In rodent liver, α1 and α2 are expressed with similar levels, while β1 and γ1 are the major regulatory subunit isoforms [37]. Different from human heart, the isoforms with γ1 subunit are more predominant in rodent heart [36].

AMPKα subunits

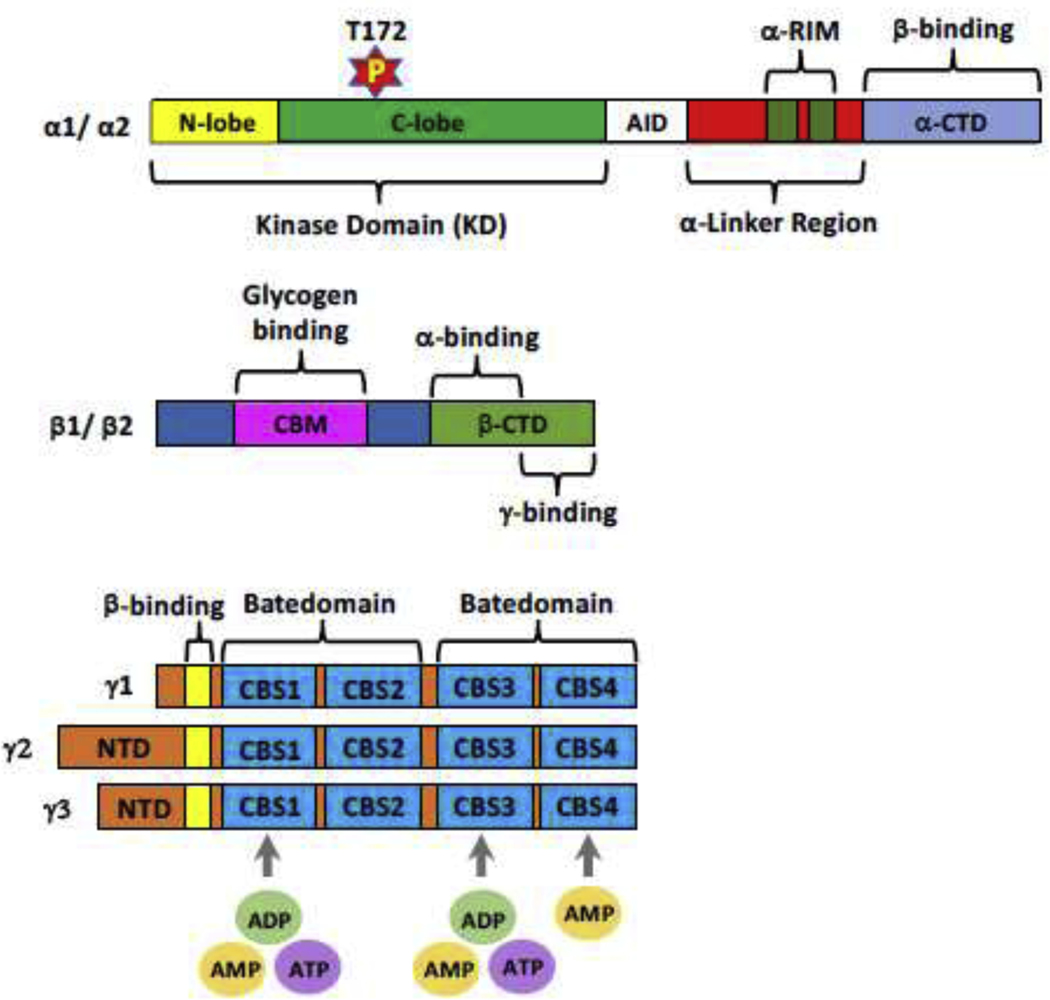

AMPKα subunits consist of kinase domain (KD) containing N-lobe and C-lobe, autoinhibitory domain (AID), α-regulatory subunit-interacting motif (α-RIM) in linker peptides (α-linker), followed by the α-subunit carboxy-terminal domain (α-CTD) which binds to β subunits [38, 39]. The T172 residue within C-lobe is phosphorylated by upstream kinases such as LKB1 and CaMKK2, which largely accounts for the activation of AMPK complex [8, 10] (Fig. 1). Several small molecules such as 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) and PF-739 have been designed to target T172 phosphorylation of α-subunits, thereby manipulating AMPK activity [31, 40]. AID could compromise AMPK activity approximately tenfold, while removal of AID leads to constitutive activation of AMPK [39, 41]. Followed by AID, α-RIM (also known as α-hook) containing about 60 amino acids is essential for nucleotide-dependent regulation of AMPK [42, 43].

Fig.1. Functional domain of AMPK subunits.

Kinase domain (KD) of AMPKα subunits contains N-lobe and C-lobe and threonine 172 (T172) for phosphorylation by upstream kinases at C-lobe, followed by autoinhibitory domain (AID), aregulatory subunit-interacting motif (α-RIM) in linker peptides (α-linker) and α-subunit carboxy-terminal domain (α-CTD) which binds to b subunits. The functional domains of β-subunits include carbohydrate-binding module (β-CBM), binding to glycogen, and β-subunit C-terminal domain (β-CTD) which interacts with both α-subunits and the γ-subunits. Four tandem repeats of CBS motifs (CBS1, CBS2, CBS3 and CBS4) and two CBS repeats form a Batedomain in AMPKγ subunits are in charge of binding to adenine nucleotides (AMP, ADP or ATP) except for CBS2 motif.

AMPKβ subunits

AMPKβ subunits contain two functional domains including β-subunit carbohydrate-binding module (β-CBM) which associates with glycogen or starch in mammals and β-subunit C-terminal domain (β-CTD) which interacts with both the α-CTD and the γ-subunit (Fig. 1). AMPK complex phosphorylates glycogen synthase via the binding between β-CBM and glycogen, leading to the inactivation of glycogen synthase [44, 45]. Moreover, β-CBM also interacts with N-lobe of the kinase domain of α subunit through the surface opposite to its glycogen binding site [46, 47]. Importantly, the cleft between β-CBM and α subunit forms the binding site for ligands acting on AMPK, which is called allosteric drug and metabolite (ADaM) site. Once ligands bind to ADaM site, AMPK can be allosterically activated [46, 48].

AMPKγ subunits

ΑΜPΚγ subunits contain four tandem repeats named CBS1, CBS2, CBS3 and CBS4. Two CBS repeats assemble a Batedomain which binds to adenine nucleotides such as AMP, ADP and ATP (Fig. 1). In AMPKγ, the four CBS repeats in the γ-subunits form a flattened disk containing four potential adenine nucleotides-binding sites [49, 50]. In accordance with crystal structure of mammalian AMPK complexes, three AMP binding sites (sites 1, 2 and 3) identified within CBS1, CBS3 and CBS4 motifs respectively display conserved aspartate residue [51, 52]. In mammalian γ1 subunit, sites 1 and 2 represent the regulatory sites and are critically involved in the competition of AMP with ADP or ATP, whereas site 3 shows tight interaction with AMP, indicating that this non-exchangeable site is dispensable for AMP/ATP sensing [37]. In addition, ADP could also bind to two exchangeable adenine nucleotides binding sites on γ subunit, which in turn protects the enzyme from dephosphorylation without causing allosteric activation [38].

AMPK ACTIVATION

Adenine nucleotides dependent activation

AMPK is activated through both canonical and non-canonical regulation. AMPK, so called AMP-activated protein kinase, could be allosterically activated by 5’-AMP, a process referred as canonical adenine nucleotides dependent regulation [53, 54]. The association of AMP with AMPK leads to the enhancement of AMPKα T172 phosphorylation while inhibition of AMPKα T172 dephosphorylation, resulting in allosteric activation of AMPK complex. It has been demonstrated that LKB1 facilitates phosphorylation of AMPKα on T172 in response to elevated AMP/ATP ratio [47]. AMP has also been reported to promote AMPK T172 phosphorylation leading to allosteric activation of AMPK [55]. In addition, myristoylation of β subunit is required for adenine nucleotides-stimulated AMPKα T172 phosphorylation [56, 57]. Remarkably, AMPKγ subunits containing four CBS repeats whose structures have been solved with AMP, ADP and/or ATP bound at different sites [52, 58] play an important role in both T172 phosphorylation of AMPKα and allosteric activation of the whole complex [38, 52, 58, 59]. The R531G mutation in the AMPKγ2 subunit frequently observed in human heart disease abrogates allosteric activation and AMPKα T172 phosphorylation by AMP [60].

Activation via ADaM binding sites

Interestingly, the association of ligands with ADaM binding sites also leads to the activation of AMPK by protecting AMPKα T172 residue from dephosphorylation, in addition to nucleotide-binding [46, 48, 51]. Ligand binding at ADaM sites may potentiate the interaction between β-CBM and α-kinase domain, thereby abolishing dephosphorylation of AMPKα [51]. Furthermore, β1 subunit phosphorylation on Serine 108 (S108) residue also accounts for another important mechanism for AMPK activation by ADaM site ligand, A769662 [48]. Of importance, phosphorylation of S108 on β1 subunit enhances the binding affinity of ligands (A769662 and 991) at ADaM site [51]. Notably, the integrity of AMPK complex is indispensable for allosteric activation by ADaM site ligands. Crystal structure analysis reveals that outside of CBM consensus sequence of β subunit directly interacts with α-helix C region of the kinase domain (referred to as the C-interacting helix) of α subunit [51]. Mutation of Leucine 166 residue in the C-interacting helix dampens the association between α and β subunits, thus significantly compromising allosteric activation of AMPK by 991 [51]. All the evidence indicates that both the integrity of AMPK complex and β subunit phosphorylation are required for allosteric activation of AMPK by ADaM site ligands such as A769662 and 991. In addition, salicylate, a natural compound derived from willow bark, directly activates AMPK via binding to the ADaM site [25]. AMPK heterotrimers with various subunits combination display different binding affinity with ADaM site activators. For example, PF249 and PF06409577, the other two ADaM site activators, bind more tightly to β1-containing than to β2-containing AMPK complexes [32]. However, PF739 and MK-8722 both effectively bind to β1- or β2-containing AMPK complexes [31, 33]. Given that either nucleotide-binding to γ-CBS domain or ligand binding to ADaM sites can activate AMPK, it is conceivable that combination treatment targeting both nucleotide-binding and ADaM binding sites on AMPK complexes may lead to more robust and efficient activation of AMPK, representing the promising strategy to target AMPK for therapy [61–64].

Adenine nucleotides independent activation

AMPK activation can also be modulated in an adenine nucleotides independent manner, referred as non-canonical regulation. For decades, it has been speculated that decrease of AMP/ATP ratio serves as the main mechanism accounting for glucose deprivation induced AMPK activation. Thus, it is widely accepted that AMPK is activated through canonical adenine nucleotides dependent regulation under glucose restriction condition. However, the kinetic model suggests that only glucose removal is able to rapidly activate AMPK within 15 minutes without impact on the intracellular ADP/ATP or AMP/ATP ratio within the same time range, although complete restriction of carbon source could trigger more substantial and sustained activation of AMPK, correlated with elevated AMP/ATP ratio [65, 66]. These findings indicate that glucose deprivation alone activates AMPK in a fast but AMP/ADP-independent manner, while complete or prolonged removal of carbon source leads to hyperactivation of AMPK in a delayed and AMP/ADP-dependent manner. In line with this, cells with AMPKγ2 R531G mutation, insensitive to enhanced intracellular AMP or ADP level, still display rapid AMPK activation upon glucose deprivation [66], indicative of the other mechanism involved in low glucose driven AMPK activation. Recent study uncovers the glycolytic enzyme, aldolase, appears to play a non-canonical role for AMPK activation under glucose deprivation. Aldolase promotes the formation of lysosomal complexes containing the v-ATPase, Ragulator, AXIN, LKB1 and AMPK under glucose deprivation, leading to LKB1 mediated AMPKα T172 phosphorylation irrespective of the ADP/ATP or AMP/ATP [65]. In the glucose proficient condition, Fructose-1,6-biphosphate (FBP), a glycolytic intermediate generated from glycolysis, binds to aldolase and disrupts the association of AXIN/LKB1 with v-ATPase/Ragulator, resulting in defective AMPK activation [65]. Thus, aldolase serves as a new modulator for AMPK activation by sensing cellular FBP availability from glucose metabolism. Glucose starvation relieves the inhibitory effect of FBP on aldolase-mediated lysosome complexes formation, thereby facilitating AMPK activation in an adenine nucleotides independent manner [65].

Apart from glucose deprivation, intracellular Ca2+ ions can indirectly activate AMPK through CaMKK2 activation without alteration of adenine nucleotide levels. Other physiological stimuli including hypoxia, oxidative stress or growth factor stimulation could also activate AMPK without the change of AMP/ATP ratio [67]. Interestingly, AMPK activation can be also induced by DNA damage partially through ATM-LKB1 cascade [68–70]. However, other mechanisms through yet to be discovered are also involved in DNA damage induced AMPK activation [71]. Future studies aiming at identifying the additional mechanisms by which diverse stresses induce AMPK activation will be warranted to further unravel the complexity for AMPK activation.

DOWNSTREAM TARGETS OF AMPK

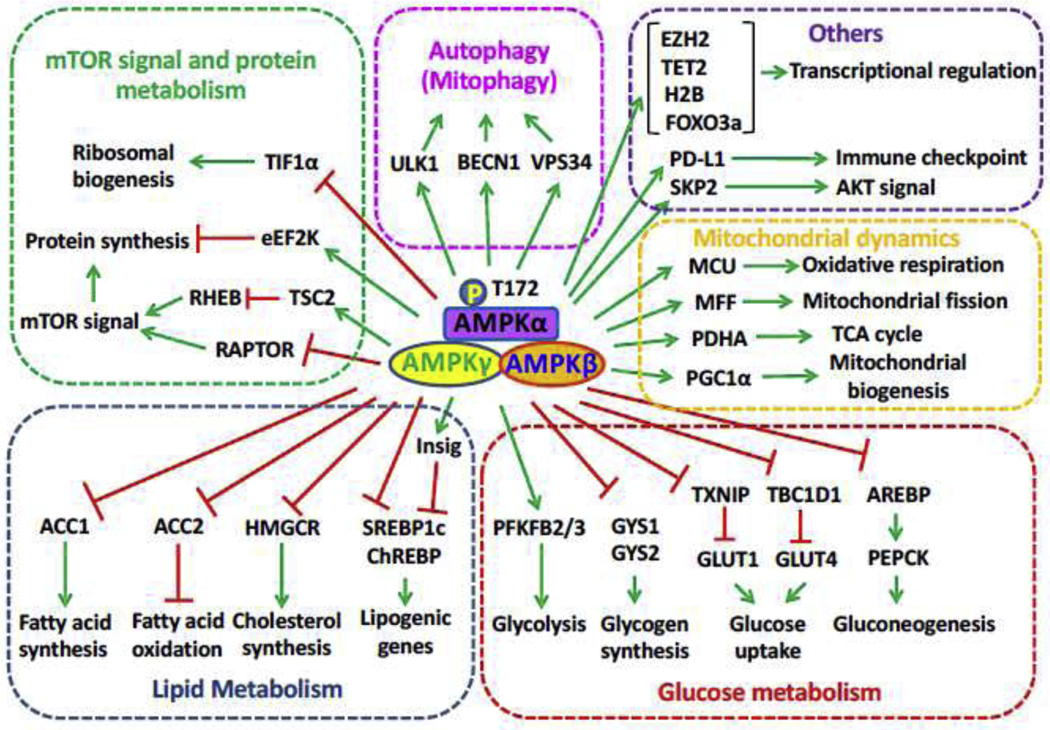

As a kinase, AMPK regulates diverse biological processes primarily through phosphorylating its downstream targets. In essence, AMPK recognizes and phosphorylates its substrates through a consensus motif with hydrophobic residues at −5 and +4 positions of actual phosphorylation site [72]. The consensus motif has been identified including LRRVXSXXNL, MKKSXSXXDV, IXHRXSXXEI via quantitative phosphoproteomics datasets [72]. In addition, basic residues at −3 or −4 position and neutral polar residues (usually Serine) at −2 position are regarded as secondary AMPK consensus motif [73]. However, some AMPK targets such as H2B [74] with Arginine (R) at −5 position and PGC1α [75] with Asparagine (N) and Phenylalanine (F) at −5 position for two phosphorylation sites, respectively, suggesting the flexibility and complexity of AMPK consensus motif. Below are some key substrates of AMPK whose phosphorylation by AMPK critically regulates their activity and functions in diverse biological processes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Physiological role modulated by downstream substrates of AMPK.

Protein synthesis, autophagy/mitophagy, lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism and transcriptional regulation are modulated by AMPK via phosphorylating its downstream substrates.

ACC

ACC (Acetyl-CoA carboxylase) is critically involved in fatty acid metabolism. Two isoforms of ACC (ACC1 and ACC2) have been identified, and both of which catalyze the carboxylation of Acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA. Unlike cytoplasmic ACC1, which plays an essential role in fatty acids synthesis, ACC2 is associated with mitochondria [76] and serves as a negative regulator for β-oxidation through allosteric inhibition of CPT-1 (carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1) critically involved in β-oxidation [77]. AMPK mediated phosphorylation of ACC has been unraveled for decades, and ACC1 Ser79 (S79) phosphorylation (S79 for mouse and rat, S80 for human) serves as a universal indicator for AMPK activation [78]. Although AMPK could trigger rat ACC1 phosphorylation on S79, S1200 and S1215 under in vitro condition, S79 phosphorylation is well characterized in vivo and is associated with ACC1 inactivation. Likewise, AMPK also induces S219 phosphorylation of ACC2 equivalent to S79 in ACC1, leading to impaired ACC2 activity and enhancing β-oxidation in mouse skeletal muscle [17]. Crystal structure study from yeast ACC reveals that AMPK mediated phosphorylation of ACC may dissociate the functional biotin-carboxylase domain dimer into inactive monomers, thereby repressing ACC catalytic activity [79]. It will be interesting to know whether the similar mechanism for ACC regulation can be also applied to mammalian cells.

ULK1

ULK1, together with FIP200 (focal adhesion kinase family interacting protein of 200 kDa), ATG13 (autophagy-related protein 13), and ATG101, serves as an important regulator for autophagy to maintain protein homeostasis, especially under nutrient starvation condition, by initiating the formation of autophagosome [80]. AMPK phosphorylates ULK1 on multiple sites from numerous studies including S467, S555, T574, S637 [23, 81], S317 and S777 [82]. Of note, AMPK mediated phosphorylation on ULK1 appears to be essential for ULK-mediated autophagy or mitophagy and cell survival upon stress [23, 82]. Other study reported that human ULK1 is hyper-phosphorylated on S638 and S758 (equivalent to S637 and S757 in mouse) under nutrient proficient condition, but dephosphorylation on S638 followed by S758 dephosphorylation occurs upon nutrient starvation. Importantly, phosphorylation of ULK on S638 and S758 is mediated by active mTOR under nutrient proficient condition, and dephosphorylation of ULK1 on S758 drives its dissociation with AMPK and activates ULK to elicit autophagy [81]. Interestingly, basal AMPK binds to ULK1 and limits its function by phosphorylating S638 under steady state, but activated AMPK promotes autophagy through phosphorylating ULK1 on more sites in response to starvation [81]. Thus, AMPK plays a dual role in mediating ULK1 phosphorylation towards autophagy regulation. Although AMPK-mediated ULK1 phosphorylation in governing autophagy has been unraveled for years, the exact phosphorylation sites and detailed mechanism underlying this process are still under debate.

MFF

Dynamic mitochondrial homeostasis between fusion and fission is essential for mitochondrial health and function [83, 84]. In general, mitochondrial fusion maximizes the energy production in response to mild nutrient shortage, while severe nutrient deprivation leads to mitochondrial fission and fragmentation followed by mitophagy [85]. MFF (mitochondrial fission factor), as a critical component of mitochondrial fission sensor, functions in the recruitment of DRP1 (dynamin-related protein 1) to the outer membrane of mitochondria to initiate fission process by inducing membrane constriction and scission [86]. AMPK elicits MFF phosphorylation on S155 and S172 upon energy stress [22]. Notably, compared with WT MFF, restoration of AMPK nonphosphorylatable SA2 (S155A, S172A) mutant MFF into Mff−/− MEFs attenuates the recruitment of DRP1 to mitochondrial outer membrane in response to AICAR or rotenone treatment. Interestingly, re-introduction of phosphomimetic SD2 (S155D, S172D) or SE2 (S155E, S172E) mutant MFF into Mff−/− MEFs leads to enhanced mitochondrial fragmentation even without extracellular stimuli, comparable to those cells with WT MFF restoration upon AICAR induction [22]. Thus, AMPK mediated phosphorylation of MFF on S155 and S172 critically drives mitochondrial fission process by facilitating the recruitment of DRP1.

TSC2 and RAPTOR

mTORC1 consisting of diverse proteins serves as the central regulator governing cell metabolism, survival, proliferation and growth, whose dysregulation results in various diseases including cancer and diabetes [18]. TSC2 (Tuberous sclerosis complex 2, also known as Tuberin) with GTPase activating protein (GAP) activity severs as a critical negative regulator of mTORC1 through inhibiting RHEB GTPase, which functions as a direct activator of mTORC1 [87]. TSC2 phosphorylation by mitogen-activated kinases including AKT, ERK, and RSK leads to its inactivation, in turn stimulating mTORC1 signaling [88]. In contrast, phosphorylation of TSC2 on T1227 and S1345 by AMPK in response to energy deprivation enhances the activity of TSC2 leading to impaired mTORC1 activity and protein translation [89, 90]. Thus, AMPK dependent TSC2 phosphorylation regulates protein homeostasis in response to various energy conditions [90].

Accumulated evidence reveals that TSC2 may not be the only substrate of AMPK for its regulation on mTORC1 signaling. First, although the negative correlation between mTORC1 and AMPK activation is observed throughout all eukaryotes, including C. elegans and S. cerevisiae, TSC2 ortholog has not been identified in either of those species [91], suggesting AMPK governs mTORC1 signaling through other mechanism in these species. Second, AMPK activation by AICAR or phenformin still profoundly compromises mTORC1 signaling in Tsc2 −/− MEFs or other TSC2 deficient cells [92, 93]. Using bioinformatic analysis based on AMPK consensus motif, mTOR binding protein RAPTOR [94] has been revealed as an ideal AMPK substrate. Further experiments demonstrated that AMPK phosphorylates RAPTOR on S722 and S792, and this phosphorylation is essential for energy stress-induced mTORC1 inhibition [93]. Mechanistically, RAPTOR phosphorylation by AMPK promotes the interaction of RAPTOR with 14–3-3 proteins, thus leading to inactivation of mTORC1, cell cycle arrest and cellular apoptosis upon metabolic stress.

Collectively, AMPK compromises mTORC1 activity through phosphorylating both TSC2 and RAPTOR, placing AMPK as a key energy sensor in coordinating cell growth and proliferation under distinct energy statuses.

H2B

Posttranslational modifications including phosphorylation on histones are critically involved in transcription regulation [95, 96]. The involvement of AMPK in transcriptomic reprogramming to elicit long term adaptation of cells to various stress conditions has been documented in multiple studies, although the mechanism underlying this regulation remains largely unknown [97]. The core histone H2B is phosphorylated by AMPK on S36 in response to metabolic stress [74]. Importantly, H2B S36 phosphorylation is abrogated in both Lkb1−/− and Ampk−/− MEFs upon energy stress or AMPK activators, suggesting LKB1 likely acts through AMPK activation to stimulate H2B S36 phosphorylation in response to diverse metabolic stresses. Further, S36 phosphorylation on H2B is required for its interaction with AMPK. ChIP analysis reveals that a positive correlation between AMPK and H2B S36 phosphorylation in the gene transcribed region is observed in response to glucose deprivation and UV treatment [74]. Interestingly, AMPK appears to be specifically recruited to the promoter region of p53 target genes such as p21 and cpt1c, reminiscent of the previous observation that AMPK induces a metabolic checkpoint in a p53 dependent manner [98]. Moreover, enhanced co-localization between AMPK and H2B S36 phosphorylation at p53 binding site and also along the transcription region is observed, suggesting AMPK, via H2B S36 phosphorylation, cooperates with p53 to modulate gene transcriptional elongation to elicit adaptive response, thus likely protecting cells from cell death upon stress conditions. Indeed, ablation of H2B S36 phosphorylation compromises RNA polymerase II association to transcribed region, leading to impaired transcription of AMPK target genes and reduced cell survival upon stresses [74]. Whether AMPK could similarly govern other stress-induced transcription factors such as FOXO3a [99] and PGC1α [100] through mediating H2B phosphorylation warrants further investigation.

SKP2

Ubiquitination, as an essential post-translational modification, plays an important role in diverse cellular and biological processes through maintaining protein homeostasis and activity [101]. SKP2, as a critical oncogenic F-Box E3 ligase [102], is involved in both protein degradation through mediating K48-linked ubiquitination [103] and non-proteolytic function by conjugating K63-linked ubiquitination [104]. Notably, activation of AMPK, via CaMKK2 upon EGF stimulation, could induce SKP2 phosphorylation on S256, thus promoting the interaction between SKP2 and Cullin1 to maintain the integrity of SKP2-SCF complex [67]. Moreover, AMPK mediated SKP2 phosphorylation on S256 is required for SKP2 E3 ligase activity to elicit K63-linked ubiquitination on AKT, leading to the activation of AKT and subsequent oncogenic processes [67]. Further, AMPK also protects cancer cells from hypoxia or glucose deprivation induced cell death partially through orchestrating SKP2 S256 phosphorylation and subsequent AKT activation [67]. Importantly, AMPK/SKP2 S256 phosphorylation/AKT cascade is activated in advanced breast cancer and its activation predicts poor survival outcome of breast cancer patients, indicating the targeting AMPK or AMPK mediated SKP2 phosphorylation is a novel strategy for breast cancer therapy. Given that SKP2 E3 ligase activity is indispensable for cellular response to other stress conditions such as DNA damage [105] and oxidative stress [106], it would be interesting to determine whether SKP2 phosphorylation on S256 by AMPK is also involved in these adaptive responses.

PDHA

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) is a multi-enzyme complex and acts as a rate-limiting enzyme to maintain TCA cycle by catalyzing pyruvate to Acetyl-CoA [107]. The activity of PDHc largely depends on the phosphorylation status on its catalytic subunit PDHA. PDH kinase (PDHK) mediated PDHA phosphorylation on S293 serves as a negative signal to suppress the activation of PDHc [108]. Dephosphorylation of PDHA S293 site ensures the activity of PDHc to maintain TCA cycle through facilitating pyruvate metabolism, although the underlying mechanism remains elusive. Recently, AMPK is found to co-localize with PDHA in mitochondrial matrix and serve as a direct kinase to drive sequential PDHA phosphorylation on S314 and S295 sites [15]. Interestingly, PDHA S314 phosphorylation serve as a prime signal to compromise the interaction of PDHA with PDHK, resulting in the attenuated phosphorylation on S293. Due to the steric effect, dephosphorylation of S293 would provide space for AMPK to further induce PDHA phosphorylation on its neighboring S295 residue, which acts as an intrinsic catalytic site essential for PDHc activation and pyruvate metabolism [15]. Surprisingly, even with impaired S293 phosphorylation, PDHc with dephosphorylation on PDHA S295 site still largely compromise its ability to catalyze pyruvate to Acetyl-CoA [15], highlighting the essential role of AMPK mediated PDHA S295 phosphorylation in maintain PDHc activity [109]. Functionally, activation of AMPK-PDHc axis facilitates breast cancer lung metastasis through rewiring the metabolic pathway of cancer cells from glycolysis to TCA cycle, thus enabling disseminated cancer cells to cope with diverse stresses in the metastatic microenvironment [15]. Since dysregulation of TCA cycle is associated with multiple metabolic disorders including diabetes [110], obesity [111] and Alzheimer’s disease [112], AMPK mediated PDHA phosphorylation and PDHc activation may contribute to the development of these pathological disorders.

REGULATION OF AMPK EXPRESSION AND ACTIVITY

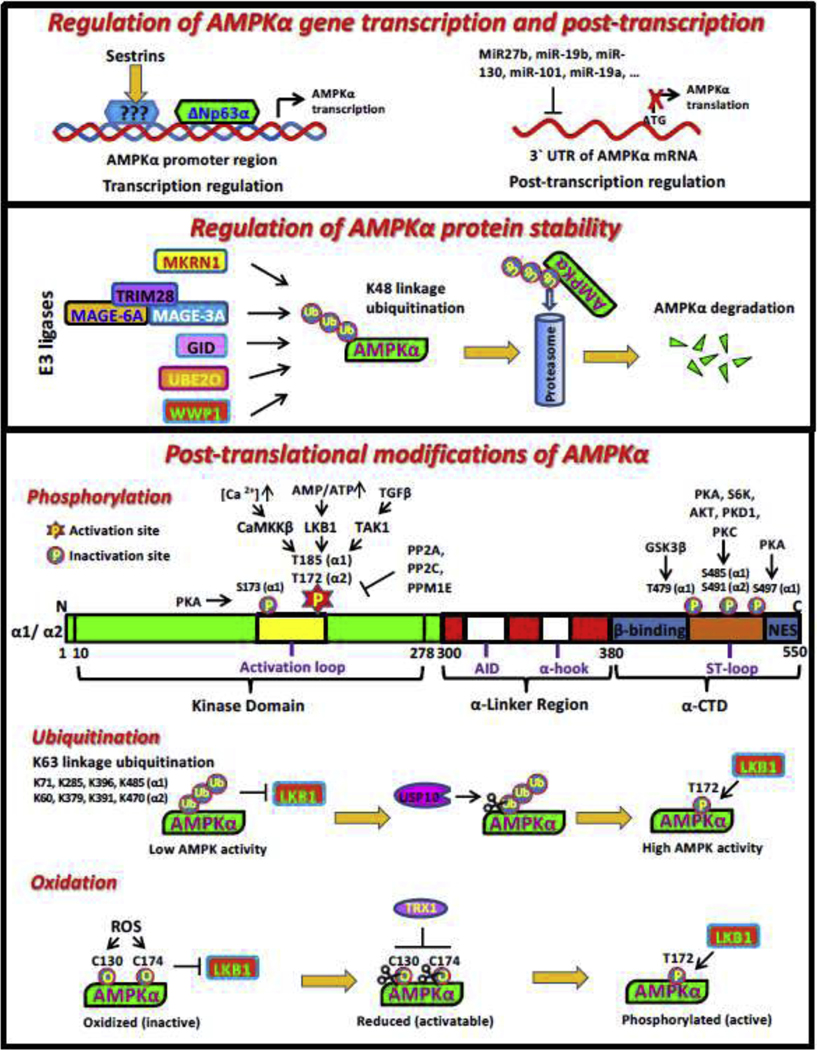

Dysregulation of AMPK activity is linked to aging process and various human diseases including metabolic syndrome, stroke, cardiovascular disease and cancer [113]. As the critical catalytic subunit, AMPKα expression and its kinase activity are tightly controlled through multiple layers of regulation including transcription, protein stability, and post-translational modifications under physiological condition (Fig. 3). We will briefly summarize how AMPK is regulated through transcription and post-translational modifications in this section.

Fig. 3. Regulation of AMPK by transcription, protein stability and post-translational modifications.

AID, autoinhibitory domain; CTD, C terminus domain; NTD, N terminus domain; CBM, carbohydrate-binding module; CBS, cystathionineb-synthase repeats; RIM, regulatory-subunit-interacting motif; ST-loop, serine/threonine-enriched loop

Regulation of AMPK expression

Transcription regulation and post-transcriptional regulation

ΔNp63α, the predominant p63 isoform expressed in epithelial cells, has been identified as a crucial transcription factor for AMPKα1 transcription. Four putative p63 binding element (CNNGNNNNNNCNNG) [114] on AMPKα1 promoter have been identified. Notably, ectopic expression of ΔNp63α, but not the DNA-binding defective mutant ΔNp63αC306R, significantly elevates AMPKα1 mRNA expression, suggesting ΔNp63α likely serves as a direct transcription factor to transactivate AMPKα1 gene expression [115].

Sestrins are stress-induced proteins conserved throughout the species. Enhanced sestrin proteins account for the acquired metabolic benefits of exercise [116]. Interestingly, sestrins could compromise mTORC1 signaling by activating AMPK [117]. Further, sestrins are found to not only physically associate with AMPK, but also modulate the transcription of AMPK subunits including AMPKα1 and AMPKβ1 [118], although the underlying mechanism and transcription factors involved remain unclear.

MicroRNAs (miRs), as single-strand non-coding RNAs, typically compromise the translation of target mRNAs through recognizing the complementary sequences of 3ÙTR regions, thus governing gene expression [119]. MiR-27b is shown to target AMPKα2 and leads to its downregulation. Moreover, pharmacological ablation of MiR-27b in mice improves the neurogenesis and neurological function upon permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in an AMPK-dependent manner [120]. Through in silico study, AMPKα1 3` UTR region contains multiple recognition sites of miR-19b, miR-130, miR-101, and miR-19a [121], indicating that AMPKα1 expression may be also regulated by these miRs.

Regulation of AMPK protein stability

Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is essential for the protein homeostasis through tightly regulating protein degradation [122]. The role of UPS in governing AMPK function in response to energy and metabolic stresses has started to emerge.

Makorin ring finger protein 1 (MKRN1), as an E3 ligase, is linked to tumorigenesis and adipocyte differentiation by mediating ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of its target proteins such as p53 and PPARγ [123, 124]. Recently, MKRN1 is identified as a direct E3 ligase for AMPKα subunit (AMPKα1 and AMPKα2) and mediates proteasome-dependent degradation of AMPKα subunit [125]. Interestingly, MKRN1 depletion leads to the accumulation of AMPKα proteins, without impacts on AMPKβ and AMPKγ protein level, suggesting the specific role of MKRN1 in the regulation of AMPKα subunit. Notably, Mkrn1 null mice display chronic AMPK activation in the liver as well as white and brown adipose tissues, indicative of enhanced AMPK signal upon Mkrn1 deficiency in vivo. Moreover, activated AMPK in Mkrn1 null mice prevent high fat diet induced metabolic syndromes including insulin resistance, obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [125], which could be reversed by the genetic ablation of AMPK. As MKRN deficiency alleviates obesity and its related comorbidities through AMPK activation, targeting MKRN to boost AMPK signal represents a potential strategy to treat metabolic syndromes.

MAGE-A3 and MAGE-A6 are expressed mostly in testis [126], but aberrantly activated during malignant transformation to drive robust anchorage-independent growth and cancer metastasis [127, 128]. Interestingly, MAGE-A3/6 is found to specifically associate with TRIM28 E3 ubiquitin ligase and targets ubiquitination and proteolysis of p53 [129, 130], accounting for the oncogenic property of MAGE-A3/6. Using systematic protein arrays containing more than 9,000 recombinant proteins for screening additional substrates, AMPKα1 is identified as the most consistent and robust target of MAGE-A3/6-TRIM28 [131]. Depletion of MAGE-A3/6 or TRIM28 results in the elevation of AMPKα1 protein level without affecting its mRNA level. Conversely, ectopic expression of MAGE-A3 in MAGE-A3/6 deficient cells promotes proteasome-dependent AMPKα1 degradation [131]. As such, restriction of AMPKα1 by MAGEA3/6-TRIM28 is associated with mTOR activation, leading to impaired autophagy. Notably, enhanced anchorage-independent growth upon MAGE-A6 overexpression is compromised by the treatment of AMPK agonists such as AICAR and metformin, suggestive of a potential strategy for targeting MAGE-A3/6-positive tumors by inducing AMPK activation. Collectively, AMPKα1 is a bona fide substrate of MAGE-A3/6-TRIM28 E3 ligase complex whose inactivation accounts for oncogenic activity regulated by MAGE-A3/6.

GID (glucose induced degradation deficient) ubiquitin ligase complex has been shown to be another E3 ligase targeting phosphorylated AMPKα for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thus preventing sustained activation of AMPK upon prolonged starvation [132]. Remarkably, depletion of GID complex components in C. elegans. drives AMPK hyperactivation and profoundly enhances the lifespan partially due to mTOR inactivation [132].

UBE2O (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2O), unlike the traditional E2 ubiquitin-conjugation enzyme, acts as an E2/E3 hybrid ubiquitin-protein ligase that contains both E2 and E3 ligase activities [133]. AMPKα2 appears to be a direct substrate of UBE2O, as UBE2O could directly induce K48-linked ubiquitination of AMPKα2 on Lys (K) 470, which is conserved among various species, in the presence of only the E1 enzyme, thus leading to degradation of AMPKα2 [134]. However, this K470 residue is replaced by Arginine (R475) in AMPKα1, likely accounting for the selective ubiquitination of AMPKα2 by UBE2O. As such, the protein expression level of AMPKα2, but not AMPKα1, is robustly elevated in Ube2o−/− mouse tissues, further confirming the specificity of AMPKα2 degradation by UBE2O. In MMTV-PyVT and TRAMP transgenic mouse models, UBE2O deficiency attenuates breast cancer and prostate cancer progression and metastasis, which could be rescued upon Ampkα2 ablation [134], underscoring the oncogenic role of UBE2O in cancer regulation through promoting AMPKα2 degradation.

Additionally, WWP1 (WW domain-containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1) could also associates with and downregulates AMPKα2 in response to high energy status [135]. However, it remains to be determined whether WWP1 could directly target AMPKα2 for ubiquitination and degradation. Moreover, Cidea interacts with AMPK complex in the endoplasmic reticulum through specific association with AMPKβ subunit, leading to its ubiquitination and degradation [136]. Enhanced expression and enzyme activity of AMPK observed in Cidea−/− mice critically overcome diet induced obesity by facilitating energy expenditure [136].

Collectively, these studies underscore the importance of UPS in the regulation of various subunits of AMPK complex, thereby affecting enzyme activity and biological functions of AMPK.

Post-translational modifications of AMPK

Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation on T172 residue of AMPK α subunit (T185 in AMPKα1, T172 in AMPKα2) bolsters the activity of AMPK complex up to 100 fold [19]. LKB1 is the well characterized upstream kinase mediating AMPKα T172 phosphorylation in response to elevated AMP/ATP ratio under metabolic stress [8]. LKB1 inactivation through disruption of LKB1-STRAD-MO25 complex abolishes AMPK activation [137, 138]. CaMKK2 is another well defined kinase for AMPK activation by phosphorylating AMPK at T172 [12, 67]. It appears that TAK1 (TGF-β-activated kinase 1) may be the third kinase for AMPKα T172 phosphorylation, since TAK1 along with TAB1 (TAK1-binding proteins) could also stimulate AMPKα T172 phosphorylation both in vitro and in vivo [139]. However, the notion that TAK1 could act as a direct kinase is still under debate [140].

A recent study indicates that activation of LKB1/AMPK axis upon energy stress elevates the expression of the long non-coding RNA NBR2 (neighbor of BRCA1 gene 2), which then binds to the kinase domain of AMPKα subunit and boosts its T172 phosphorylation and activation irrespective of LKB1 status [141]. This feed-forward loop is considered necessary for the maintenance of AMPK activity in response to long-term energy crisis [142], but the detailed mechanism by which NBR2 governs AMPK activation remains elusive.

AMPKα T172 dephosphorylation leads to AMPK inactivation. This dephosphorylation process is mediated by at least three phosphatases including protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) [143], protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) [144] and Mg2+-/Mn2+-dependent protein phosphatase 1E (PPM1E) [145]. Of note, the binding of AMPKγ to AMP during energy stress relieves the inhibitory effect of these phosphatases on AMPKα T172 phosphorylation, leading to AMPK activation [146].

Additionally, phosphorylation on other residues, especially in ST-loop of AMPKα, by other kinases serves as a negative signal for AMPK activation [147]. PKA (cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase) and AKT mediated phosphorylation of S485 in AMPKα1 (S491 in AMPKα2) limits AMPK activation through antagonizing T172 phosphorylation during gluconeogenesis or insulin stimulation [148, 149]. Similarly, S6K-mediated phosphorylation on S491 of AMPKα2 upon leptin treatment impairs AMPK activity in hypothalamus [150]. Moreover, PKA triggers AMPKα1 phosphorylation on multiple residues including S173, S485, S497 in adipocyte context, and S173 phosphorylation impedes LKB1 mediated phosphorylation on T172 likely due to the potential steric hindrance, leading to AMPK inactivation and promoting lipolysis [151]. Several other kinases could also drive AMPKα phosphorylation include GSK3β (T479 in AMPKα1) [152], PKD1 (S491 in AMPKα2) [153] and PKC (S485 in AMPKα1) [154], indicative of the comprehensive regulation of AMPK activity by multiple phosphorylation events in response to various cellular contexts.

Ubiquitination and SUMOylation

In addition to promoting classic proteolysis, ubiquitination also plays an important role in the regulation of the activity of its substrates through non-K48 linked ubiquitination [102]. Genetic ablation of UCHL3 deubiquitinating enzyme in mice specifically potentiates AMPK activity in skeletal muscle without impact on AMPK expression level, indicative of the casual linkage between ubiquitination modification and AMPK activation [155]. Further study shows that ubiquitination on AMPKα abrogates its association with LKB1, and removal of this ubiquitination by USP10 (Ubiquitin Specific Peptidase 10) is required for LKB1 mediated phosphorylation and activation of AMPK during metabolic stress [156]. Interestingly, USP10 phosphorylation on S76 residue by activated AMPK acts as a positive feed-forward loop to further amplify AMPK activity upon energy crisis [156]. Although four lysine residues on AMPKα (K71, K285, K396, K485 in AMPKα1 and K60, K379, K391, K470 in AMPKα2) are identified as potential sites for USP10-mediated deubiquitination [156], the E3 ligase(s) triggering ubiquitination on these sites remains to be determined.

SUMOylation, analogous to ubiquitination, involves conjugating small ubiquitin-like modifiers SUMOs to its targets and enhances the interaction with other proteins through SUMO-interacting motif (SIM) [157]. In yeast, Snf1, the ortholog of mammalian AMPKα, is SUMOylated on K549 residue likely by the Mms21 SUMO (E3) ligase in glucose-proficient condition [158]. SUMOylation of Snf1 leads to its inactivation through both stabilizing auto-inhibitory conformation and facilitating ubiquitination mediated degradation. Similarly, in mammalian cells, PIAS4 SUMO E3 ligase induces AMPKα1 SUMOylation on K118 and compromises AMPK activity without alteration of either AMPKα protein levels or T172 phosphorylation [159], suggesting PIAS4-mediated SUMOylation affects AMPK activity through unknown mechanism. Surprisingly, PIAS4 modulates AMPK activity specifically towards mTORC1 signal, but not other canonical substrates of AMPK such as ACC [159]. Conversely, PIASy specifically conjugates SUMO2 to AMPKβ2, but not AMPKβ1, and potentiates AMPK activity [160]. Thus, SUMOylation appears to affect AMPK activity, although the underlying mechanism need to be further studies.

Oxidation and S-glutathionylation

AMPK plays a fundamental role in protecting cells against ROS (reactive oxygen species) [15]. While ROS itself could regulate AMPK activity, the underlying mechanism is still controversial. Two mechanisms are proposed for AMPK regulation by ROS. On one hand, exposure of H2O2 boosts AMPK activation through either LKB1 or CaMKK2 dependent on various cellular contexts [8, 12]. Interestingly, both exogenous treatment of H2O2 and endogenous H2O2 generated by glucose oxidase stimulate S-glutathionylation of AMPKα subunit on Cysteine (C) 299 and C304 residues to promote AMPK activation [161]. It is likely that these modifications compromise the interaction between auto-inhibitory domain and α-helix C region of AMPKα, thus endowing AMPK activation by upstream kinases.

On the other hand, ROS may also impair LKB1-AMPK axis in certain cellular context. In cardiomyocytes, both glucose deprivation and H2O2 treatment induce the oxidation of AMPKα on C130 and C174 residues, leading to the aggregation of AMPKα and abolishing its phosphorylation and activation by upstream kinase such as LKB1 [162]. Of note, Trx1 (Thioredoxin1), which is an essential enzyme that mediates the cleavage of disulfide bonds in proteins [163], acts as an important cofactor of AMPK activation by inhibiting oxidation of AMPKα upon metabolic stress. Thus, three different pools of AMPK have been proposed: oxidized (inactive), reduced (activatable), and reduced and phosphorylated (active), and exactly which type of AMPK pools is formed could largely depends on ROS level, Trx1 activity, energy status and AMPK upstream kinase. Interestingly, activated AMPK could further upregulate Trx expression to drive a feed-forward mechanism to amply AMPK activity for maintaining the redox homeostasis. As a result, down-regulation of TRX1 upon high-fat diet consumption is associated with elevated AMPK oxidation and inactivation, leading to enhanced cardiomyocyte death and heart failure during myocardial ischemia [163], highlighting the physiological relevance of TRX1 in regulating AMPK activation.

Collectively, these studies suggest that ROS or oxidative stress has a complicated role in regulating AMPK activity, but exactly which role it plays may be influenced by various cellular contexts, different dosage and/or nature of oxidative stresses as well as diverse nutrition and energy conditions.

THE BIOLOGICAL ROLE OF AMPK IN DIFFERENT ORGANELLES

Mitochondrial functions regulated by AMPK

AMPK not only serves as a guardian for cellular energy balance, but also maintains mitochondrial homeostasis by orchestrating mitochondrial biogenesis. AMPK stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis for ATP generation that fulfill the energy demand of cells in response to metabolic stress. This is achieved by AMK-mediated transcriptional regulation of numerous mitochondrial proteins. AMPK directly phosphorylates PGC1α (peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α) on T177 and S538, leading to promoting PGC1α transcription activation to induce the expression of TFAM (Mitochondrial transcription factor A) [75]. TFAM then boosts mitochondrial biogenesis by promoting mtDNA replication and transcriptional regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis [75]. AMPK also phosphorylates chromatin remodeling proteins including methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and histone acetyltransferase 1 (HAT1) to promote mitochondrial biogenesis [164].

Mitochondrial dynamic including mitochondrial fission and fusion plays an important role in the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis in response to environmental insults. Upon energy stress, AMPK localizes to mitochondria and phosphorylates mitochondrial fission factor MFF on S146 that recruits dynamin-related Protein 1 (DRP1) to outer membrane of mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial fission [21, 22, 165]. AMPK also phosphorylates armadillo repeat-containing protein 10 (ARMC10) to orchestrate mitochondrial fission [166].

Mitophagy is a conserved biological process that degrades excessive, aged or damaged mitochondria to maintain the balance of mitochondrial mass and healthy mitochondria upon energy crisis. Acute energy depletion results in activation of AMPK, which phosphorylates ULK1 to induce mitophagy [23, 82, 167]. AMPK also phosphorylates several core autophagy/mitophagy components such as PAQR3 on T32 [168], ATG9 on S761 [169], Beclin1 on S91 and S94 [170], VPS34-associated protein RACK1 on T50 [171] and VPS34 on T133 and S135 [172] to regulate autophagy/mitophagy upon metabolic stress.

In addition, AMPK could phosphorylate mitochondrial MCU (Ca2+ uniporter) to elicit a rapid mitochondrial Ca2+ entry upon energy stress, which in turn boosts mitochondrial respiration to restore energy homeostasis [173]. AMPK also localizes in mitochondrial matrix to phosphorylate PDHA, catalytic subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc), on S295 and S314, leading to PDHc activation and TCA cycle entry [15]. Collectively, AMPK localized in different sub-fraction of mitochondria from outer membrane, inner membrane to matrix to regulate mitochondrial functions in response to metabolic stress or nutrition deprivation.

AMPK signaling at Golgi, ER, lysosome and nucleus

Interestingly, AMPK also regulates Golgi fragmentation in addition to mitochondrial fission/fusion. Upon energy stress, AMPK phosphorylates GBF1 on T1337, which is required for disassembly of Golgi apparatus and subsequent mitosis entry [174, 175]. Mechanistically, phosphorylation of GBF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF)-GTPases, by AMPK induces GBF1 dissociation from Golgi membrane, thus leading to impaired ARF1 recruitment to Golgi and Golgi fragmentation [174]. Moreover, AMPKα2, activated and phosphorylated by CaMKK2 at G2/M phase, localizes in Golgi to facilitate mitotic Golgi fragmentation and G2/M transition [176].

Lysosomes generated from the endosomes containing hydrolytic acid from Golgi apparatus provide the platform for AMPK activation via an AMP/ADP-independent mechanism upon acute glucose deprivation [65]. The assembly of active lysosome complexes containing v-ATPase, Ragulator, AXIN, LKB1 and AMPK is essential for AMPK activation, and such process requires aldolase [65]. However, how AMPK is recruited to lysosome for its activation is not well understood. It would be interesting to identify the regulators that recruit and/or maintain AMPK in lysosomes.

Additionally, the ER protein, STIM2, has been identified as a new partner of AMPK. Through sensing the enhancement of intracellular calcium level, STIM2 facilitates the association of AMPK with CaMMK2, thus promoting the activation of AMPK [177]. Interestingly, as a scaffold, STIM2 specifically modulates calcium induced AMPK activation through CaMMK2, but fails to impact on LKB1 mediated AMPK activation in response to energy stress [177]. This evidence provides the novel insight into how AMPK signal is orchestrated on ER.

Nuclear localization of AMPK is indispensable for its role in transcription regulation. Both AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 contain nuclear localization signal (NLS) in N-terminal of catalytic domain and nuclear export signal (NES) in C-terminal regulatory domain, ensuring its shuttling between nucleus and cytoplasm [178–180]. AMPK translocates into nucleus and turns on PPARα transcription, contributing to leptin-induced fatty acid oxidation during myogenic differentiation [179]. Moreover, AMPK nuclear translocation is required for the transcription of PGC-1α during myogenesis [181]. Interestingly, nuclear AMPK orchestrates circadian clock by phosphorylating and destabilizing CRY1 (circadian component cryptochrome circadian regulator 1) [182].

Collectively, subcellular localization of AMPK in Golgi, lysosome, ER and nucleus regulates mitosis, AMPK activation and gene transcription.

PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF AMPK SUBUNITS IN VIVO

Several evidence reveals the physiological functions of AMPK subunits including glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, glycogen metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis using genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs).

Ampkα2−/− but not Ampkα1−/− mice display resistance to hypoglycemic effects by AICAR, suggesting that AMPKα2 complexes mainly contribute to AMPK activation upon AICAR stimulation [183, 184]. Ampkα2 deficient mice also cause mild insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance correlated with defect of insulin secretion, whereas Ampkα1 deficient mice exhibit no obvious metabolic phenotypes [183, 184]. Interestingly, Ampkα2 deficient mice show rapid and severe ischemia contracture in heart, indicating that loss of Ampkα2 deteriorates heart functions during ischemia [185, 186].

Liver-specific deletion of Ampkα2 in mice results in mild hepatic hyperglycemia and maintains blood glucose in the physiological range under fasting [187]. Additionally, simultaneous deletion of Ampkα1 and Ampkα2 in mouse liver reduces mitochondrial biogenesis via downregulation of PGC-1α, cytochrome c oxidase I (COX I), COX IV and cytochrome c genes [188].

Muscle-specific deletion of Ampkβ1 in mice do not show detectable phenotypes, but muscle-specific deletion of Ampkβ2 in mice modestly reduces mitochondrial content and contraction-stimulated glucose uptake [189]. Notably, simultaneous deletion of Ampkβ1 and Ampkβ2 in mouse muscle dramatically reduces mitochondrial content and contraction-stimulated glucose uptake without affecting normal insulin sensitivity [189]. Moreover, both muscle-specific deletion of Ampkγ3 mice and transgenic mice overexpressing a kinase dead Ampkα2 mutant (Ampkα2-KD) do not change glycogen resynthesis after exercise [190, 191], but muscle glycogen content in skeletal muscle in transgenic mice overexpressing Ampkγ2 R225Q mutant is increased upon high exercise training [192]. Collectively, tissue-specific deletion of Ampkα2 or Ampkβ2 mice show modest phenotypes due to the functional compensation by AMPKα1 or AMPKβ2 subunit. Hence, deletion of Ampkα1α2 or Ampkβ1β2 in mice show significant phenotypes including hyperglycemia and decreased glucose uptake and mitochondrial biogenesis [189].

AMPK activation in adipocytes leads to inhibition of lipogenesis and an increase in fatty acid oxidation [193]. Consistently, Ampkα2−/− mice exhibit increased body weight and adipose tissue mass upon high fat diet treatment, indicating that loss of AMPKα2 subunit may contribute to the development of obesity [194]. In muscle cells, AMPK activation by AICAR stimulates glucose uptake and glycogen storage [195]. This observation is consistent with impaired glucose tolerance in mice with muscle-specific deletion of Ampkα2 [183, 184] and impaired glycogen storage in mice with muscle-specific deletion of Ampkγ3 [190].

THE ROLE OF AMPK IN CANCER

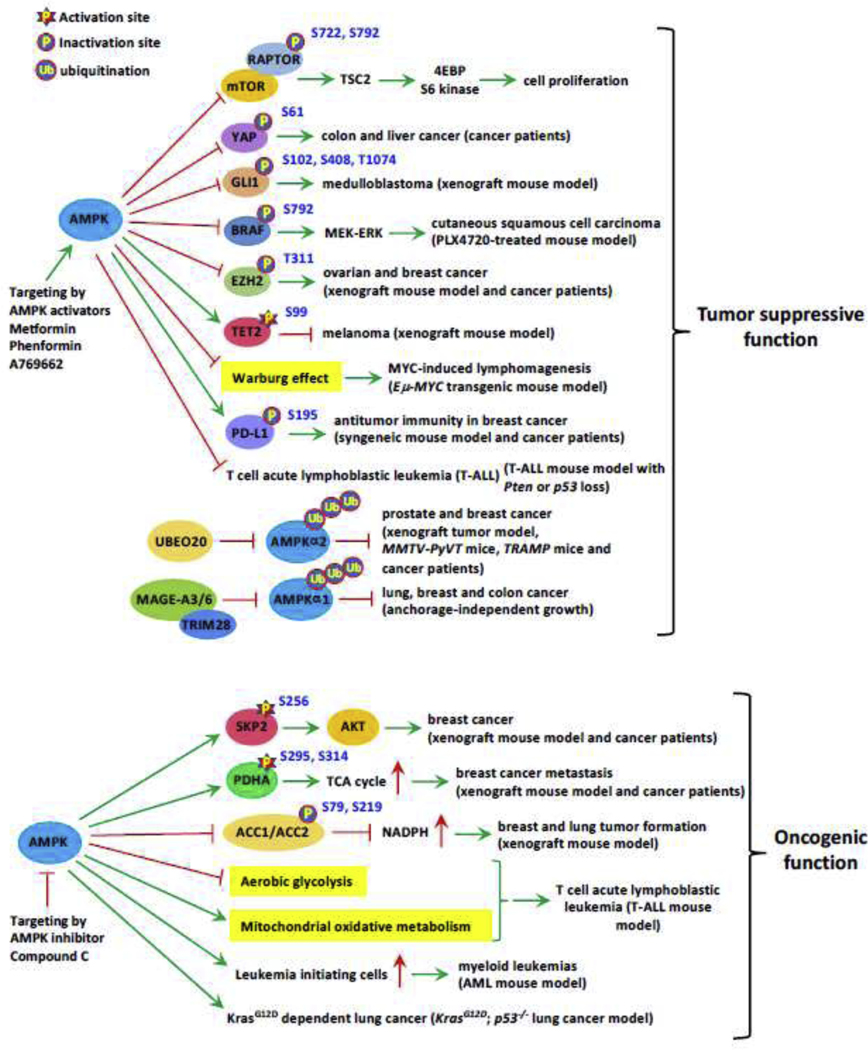

AMPK as a tumor suppressor

mTORC1 signaling, which governs protein synthesis, cell proliferation and growth, is directly inhibited by AMPK through phosphorylation of TSC2 and RAPTOR [89, 93]. Thus, AMPK is initially thought as a tumor suppressor because of its function in suppressing oncogenic mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 4). Subsequently, AMPK activation could also restrain prostate cancer cell growth partly by repressing de novo lipogenesis [196]. AMPK has been shown to cooperate with Hippo tumor suppressive signal to induce phosphorylation and inactivation of oncogenic YAP upon glucose deprivation [197]. Importantly, AMPK also phosphorylates and destabilizes GLI1, the core transcriptional factor controlling cell proliferation and differentiation involved in Hedgehog pathway, thus antagonizing its oncogenic activity in medulloblastoma [198]. Phosphorylation of BRAF on S729 by AMPK switches its binding partner from KSR1 scaffolding protein to 14–3-3 proteins, leading to the impairment of cell proliferation and cell cycle progression by compromising MEK-ERK cascades [199]. AMPK also induces cell cycle arrest by activating various tumor suppressors, such as p27, p53 and retinoblastoma protein (pRb) [98, 200, 201]. Consistently, LKB1, a well-known upstream kinase for AMPK activation, has been shown to exert tumor suppressive activity, whose loss or inactivation has been observed in diverse human cancers [202–204].

Fig. 4. Tumor suppressive and oncogenic role of AMPK regulated by various signaling cascades.

Phosphorylation of several downstream substrates by AMPK and ubiquitination or phosphorylation of AMPK by upstream enzymes contributes to inhibition or promotion of cancer progression.

Interestingly, AMPK also orchestrates epigenetic reprogramming to exert its tumor suppressive signal. AMPK has been reported to phosphorylate EZH2 on T311, which disrupts the interaction between EZH2 and SUZ12, leading to the impairment of PRC2-dependent methylation on histone H3 K27 [205]. Notably, AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of EZH2 suppresses PRC2 oncogenic function and correlates with better survival outcome in breast and ovarian cancer patients [205]. AMPK also impacts on DNA methylation through phosphorylating and activating tumor suppressor TET2 on S99 [206], which serves as a methyl-cytosine dioxygenase to convert methyl-cytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), thus preventing dysregulation of 5hmc and neoplasms. Intriguingly, metformin-mediated AMPK activation triggers checkpoint blocker PD-L1 phosphorylation on S195, resulting in PD-L1 degradation via endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD) and promotes antitumor immunity [207].

Numerous studies using genetic mouse model has supported the role of AMPK as a tumor suppressor. First, Ampkβ1 depletion in prostate promotes earlier onset of prostate adenocarcinoma in conditional Pten knockout mice [196], indicative of the tumor suppressor function of AMPKβ1 in restricting prostate cancer development. Second, MAGE-A3/6-TRIM28, a cancer-specific ubiquitin ligase, has been demonstrated to drive AMPK ubiquitination and degradation, leading to promoting mTOR signaling and malignant transformation in lung, breast and colon tissues [131]. Third, UBE2O amplified in several human cancer targets AMPKα2 for ubiquitination and degradation, in turn promoting tumor initiation and progression [134]. Fourth, loss of Ampkα1 accelerates MYC-driven lymphomagenesis by inducing HIF-1α dependent aerobic glycolysis [208, 209] Fifth, in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL) mouse model induced by Pten deficiency in thymic T cell progenitor, Ampkα1 loss in T-ALL promotes leukemia/lymphoma development [210]. Finally, Ampkβ1 depletion promotes earlier onset of T-cell lymphoma upon p53 knockout [211]. Collectively, these studies provide the proof of principle evidence that AMPK could act as a tumor suppressor to restrict cancer development at least in certain contexts.

AMPK as an oncogene

Although above studies suggest the tumor suppressive role of AMPK in certain contexts, accumulated studies have uncovered the oncogenic role of AMPK in cancer promotion in other contexts (Fig. 4). Several mechanisms have been documented to account for the oncogenic activity of AMPK. First, AMPK maintains NADPH homeostasis to promote cancer cell survival and breast cancer progression by phosphorylating and inactivating ACC1/2 [212]. Second, AMPK is also involved in EGF (epidermal growth factor)/AKT signaling, which is deregulated during malignant transformation and cancer metastasis. AMPK promotes SKP2 phosphorylation on S256 in response to EGF stimulation, resulting in the ubiquitination and activation of AKT as well as subsequent oncogenic processes [67]. Remarkably, elevated AMPK T172 phosphorylation, SKP2 S256 phosphorylation and AKT S473 phosphorylation have been detected in advanced breast cancer and significantly correlates with poor disease-specific and metastasis-free survival, highlighting the clinical significance of AMPK-SKP2-AKT axis in breast cancer progression [67]. Third, phosphorylation of PDHA by AMPK critically maintains PDHc activation and TCA cycle, leading to promoting breast cancer metastasis. Importantly, activation of AMPK-PDHc cascade predicts poor metastasis-free survival in human breast cancer [15]. Fourth, inhibition of aerobic glycolysis and promotion of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism by AMPK mitigate metabolic stress and apoptosis in T-ALL, resulting in promoting T-ALL cell survival [213]. Finally, AMPK in the bone marrow endows the cellular resistance to oxidative stress and DNA damage upon metabolic stress [214].

Two studies using genetic mouse models further provide the evidence in support of oncogenic role of AMPK in cancer promotion. 1) In an MLL-AF9 induced AML models, Ampk loss depletes leukemia-initiating cells (LIC) and delays leukemogenesis [214]. 2) In an aggressive KrasG12Dp53−/− lung cancer model, Ampk ablation markedly impairs tumor burden, indicative of the requirement of AMPK activation for tumorigenesis [215].

Collectively, AMPK could elicit numerous oncogenic mechanisms to promote cancer progression and metastasis, offering potential therapeutic strategies to target AMPK pathways for cancer treatment.

Alterations of AMPK in human cancer

Copy number alterations of AMPK pathway genes through loss- or gain of function features have been identified in diverse human cancers. These genes were retrieved from the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) database. AMPKα2 is amplified in 17 cancer types including stomach and esophageal carcinoma (STES), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), sarcoma (SARC), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), cervical squamous cell carcinoma, endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), pan-kidney cohort (KIPAN), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) and breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) [216]. Of note, whole genome sequencing to examine human cancer somatic alterations reveals that AMPK inactivation was detected in lung adenocarcinoma due to LKB1 loss or inactivation mutations, correlated with higher mTOR activity [217]. It will be interesting to know whether there are somatic alterations in other AMPK subunit genes in human cancer.

Targeting AMPK signaling by small molecules in cancers

Therapeutic targeting AMPK has been widely applied in the treatment of multiple metabolic disorders including diabetes. Since AMPK has been shown to display tumor suppressive roles in certain contexts, several small molecules that trigger AMPK activation has been tested in preclinical models for cancer targeting. For example, the clinical proven diabetic medication, canagliflozin activates AMPK and inhibits cell proliferation, survival and tumorigenicity of prostate and lung cancer cells [30]. Salicylate allosterically activates AMPK and compromises clonogenic survival in prostate and lung cancer cells. Notably, combined treatment of salicylate and metformin induces synergistically inhibition of cell survival through restricting de novo lipogenesis [218]. MT 63–78, a small molecule of AMPK activator, suppresses lipogenesis, mTORC1 pathway and tumorigenicity potential of prostate cancer cells [219]. Also, Phenformin, a metabolic drug activating AMPK, restricts tumor progression and enhances mouse overall survival in KrasG12DLkb1−/−, but not KrasG12Dp53−/− mice, suggesting that Phenformin can be used for a metabolism-based therapy in selectively targeting LKB1-deficeint NSCLC [220]. Of note, activation of AMPK by metformin has been shown to enhance antitumor immunity in combination with CTLA4 blockade to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy [207].

In addition to target AMPK itself, a specific ACC inhibitor, ND-654, or maintenance of ACC phosphorylation by AMPK suppresses hepatic lipogenesis, inflammation and hepatocellular carcinoma [221]. Hence, AMPK activation results in the inhibition of cell proliferation in part due to the disruption of de novo fatty acid synthesis which fuels cell cycle progression [222].

Given that AMPK activation also protects keratinocytes from hyperproliferation via phosphorylation and inactivation of BRAF, pharmacological treatment using AMPK agonists such as Phenformin represents a promising strategy to overcome BRAF inhibitor-induced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) [199]. Moreover, oral administration of phenformin, but not metformin, slows T-ALL progression in an AMPK dependent manner [210]. Taken together, multiple AMPK agonists display anti-tumor properties in preclinical models, although it remains to be determined whether AMPK activation indeed contributes to tumor suppression from these agents.

Because AMPK also displays tumor promoting activity in certain tumor contexts such as breast cancer and lung cancer, therapeutic strategies against AMPK can be also considered. Although compound C has been known to be as an AMPK inhibitor, it is highly toxic and displays numerous off-target effects [223–225], prohibiting it from being used for in vivo study. Thus, there is a great need to develop specific small molecule inhibitors of AMPK and then verify their efficacy in cancer targeting, ultimately offering novel and effective strategies to target those cancer driven by AMPK activation.

In summary, both AMPK agonists and inhibitors can be potentially used alone or in combination with other therapeutic strategies for cancer prevention or treatment under different tumor contexts that impacts the functional role of AMPK in acting as tumor suppression or tumor promotion.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVE

AMPK activation is regulated by diverse physiological and pathological conditions such as metabolic stress, caloric restriction, exercise, ageing and obesity. It regulates cell cycle progression, metabolism and mitochondria biology, and epigenetic reprogramming to maintain energy homeostasis and cell survival in response to diverse stresses. AMPK activity and stability can be regulated by diverse post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Through extensive studies in the past decades, AMPK has been shown to act as a double edge sword that elicits either tumor suppressive activity or tumor promoting role, which may be influenced by distinct cellular contexts, offering potential strategies to target cancer by manipulating AMPK activation and inactivation. Several outstanding questions remain to be addressed. First, it will be important in the future to dissect the mechanisms by which distinct cellular contexts impact the role of AMPK in cancer regulation. Second, since AMPK activation could promote breast cancer progression and metastasis, it will be important to develop specific AMPK inhibitors for targeting those cancers driven by AMPK activation. Third, since AMPK is activated and localized in diverse organelles including lysosome and mitochondria with unknown mechanisms, it will be important to dissect the mechanisms by which AMPK localization to distinct subcellular compartments are regulated. Finally, AMPK activity is regulated by SUMOylation through unknown mechanisms, thereby dissecting the mechanisms underlying this regulation will be critical to advance our current understanding of AMPK regulation. Understanding these key questions will not only provide new insights into AMPK signaling regulation, but also offer new paradigms and strategies for cancer targeting as well as other diseases associated with AMPK deregulation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the members in Lin’s laboratory for the inputs and suggestions throughout the course of this study. We deeply apologize to those scientists whose studies were not cited in this review due to the space limitation. This work was supported by start-up funds from Wake Forest School of Medicine, Anderson Discover Endowed Professorship award, NIH grants (R01CA182424 and 1R01CA193813) and Breast Cancer Pilot Award from Wake Forest Cancer Center supported by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA012197).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no conflicts of interest declared by the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Witters LA, Gao G, Kemp BE, Quistorff B, Hepatic 5’-AMP-activated protein kinase: zonal distribution and relationship to acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity in varying nutritional states, Arch Biochem Biophys 308(2) (1994) 413–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Winder WW, Hardie DG, Inactivation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle during exercise, Am J Physiol 270(2 Pt 1) (1996) E299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li M, Verdijk LB, Sakamoto K, Ely B, van Loon LJ, Musi N, Reduced AMPK-ACC and mTOR signaling in muscle from older men, and effect of resistance exercise, Mech Ageing Dev 133(11–12) (2012) 655–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Reznick RM, Zong H, Li J, Morino K, Moore IK, Yu HJ, Liu ZX, Dong J, Mustard KJ, Hawley SA, Befroy D, Pypaert M, Hardie DG, Young LH, Shulman GI, Aging-associated reductions in AMP-activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis, Cell Metab 5(2) (2007) 151–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Qiang W, Weiqiang K, Qing Z, Pengju Z, Yi L, Aging impairs insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle via suppressing AMPKalpha, Exp Mol Med 39(4) (2007) 535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yavari A, Stocker CJ, Ghaffari S, Wargent ET, Steeples V, Czibik G, Pinter K, Bellahcene M, Woods A, Martinez de Morentin PB, Cansell C, Lam BY, Chuster A, Petkevicius K, Nguyen-Tu MS, Martinez-Sanchez A, Pullen TJ, Oliver PL, Stockenhuber A, C Nguyen M. Lazdam JF O’Dowd, Harikumar P, Toth M, Beall C, Kyriakou T, Parnis J, Sarma D, Katritsis G, Wortmann DD, Harper AR, Brown LA, Willows R, Gandra S, Poncio V, de Oliveira Figueiredo MJ, Qi NR, Peirson SN, McCrimmon RJ, Gereben B, Tretter L, Fekete C, Redwood C, Yeo GS, Heisler LK, Rutter GA, Smith MA, Withers DJ, Carling D, Sternick EB, Arch JR, Cawthorne MA, Watkins H, Ashrafian H, Chronic Activation of gamma2 AMPK Induces Obesity and Reduces beta Cell Function, Cell Metab 23(5) (2016) 821–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hawley SA, Boudeau J, Reid JL, Mustard KJ, Udd L, Makela TP, Alessi DR, Hardie DG, Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRAD alpha/beta and MO25 alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade, J Biol 2(4) (2003) 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, Hurley RL, Witters LA, DePinho RA, Cantley LC, The tumor suppressor LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates apoptosis in response to energy stress, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(10) (2004) 3329–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Woods A, Johnstone SR, Dickerson K, Leiper FC, Fryer LG, Neumann D, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Carlson M, Carling D, LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade, Curr Biol 13(22) (2003) 2004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hawley SA, Pan DA, Mustard KJ, Ross L, Bain J, Edelman AM, Frenguelli BG, Hardie DG, Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase, Cell Metab 2(1) (2005) 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hurley RL, Anderson KA, Franzone JM, Kemp BE, Means AR, Witters LA, The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases are AMP-activated protein kinase kinases, J Biol Chem 280(32) (2005) 29060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Woods A, Dickerson K, Heath R, Hong SP, Momcilovic M, Johnstone SR, Carlson M, Carling D, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells, Cell Metab 2(1) (2005) 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Marsin AS, Bertrand L, Rider MH, Deprez J, Beauloye C, Vincent MF, Van den Berghe G, Carling D, Hue L, Phosphorylation and activation of heart PFK-2 by AMPK has a role in the stimulation of glycolysis during ischaemia, Curr Biol 10(20) (2000) 1247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Marsin AS, Bouzin C, Bertrand L, Hue L, The stimulation of glycolysis by hypoxia in activated monocytes is mediated by AMP-activated protein kinase and inducible 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase, J Biol Chem 277(34) (2002) 30778–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cai Z, Li CF, Han F, Liu C, Zhang A, Hsu CC, Peng D, Zhang X, Jin G, Rezaeian AH, Wang G, Zhang W, Pan BS, Wang CY, Wang YH, Wu SY, Yang SC, Hsu FC, D’Agostino RB Jr., Furdui CM, Kucera GL, Parks JS, Chilton FH, Huang CY, Tsai FJ, Pasche B, Watabe K, Lin HK, Phosphorylation of PDHA by AMPK Drives TCA Cycle to Promote Cancer Metastasis, Mol Cell 80(2) (2020) 263–278 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fullerton MD, Galic S, Marcinko K, Sikkema S, Pulinilkunnil T, Chen ZP, O’Neill HM, Ford RJ, Palanivel R, O’Brien M, Hardie DG, Macaulay SL, Schertzer JD, Dyck JR, van Denderen BJ, Kemp BE, Steinberg GR, Single phosphorylation sites in Acc1 and Acc2 regulate lipid homeostasis and the insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin, Nat Med 19(12) (2013) 1649–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].O’Neill HM, Lally JS, Galic S, Thomas M, Azizi PD, Fullerton MD, Smith BK, Pulinilkunnil T, Chen Z, Samaan MC, Jorgensen SB, Dyck JR, Holloway GP, Hawke TJ, van Denderen BJ, Kemp BE, Steinberg GR, AMPK phosphorylation of ACC2 is required for skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation and insulin sensitivity in mice, Diabetologia 57(8) (2014) 1693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Laplante M, Sabatini DM, mTOR signaling at a glance, J Cell Sci 122(Pt 20) (2009) 3589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Willows R, Sanders MJ, Xiao B, Patel BR, Martin SR, Read J, Wilson JR, Hubbard J, Gamblin SJ, Carling D, Phosphorylation of AMPK by upstream kinases is required for activity in mammalian cells, Biochem J 474(17) (2017) 3059–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hawley SA, Davison M, Woods A, Davies SP, Beri RK, Carling D, Hardie DG, Characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase kinase from rat liver and identification of threonine 172 as the major site at which it phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase, J Biol Chem 271(44) (1996) 27879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ducommun S, Deak M, Sumpton D, Ford RJ, Nunez Galindo A, Kussmann M, Viollet B, Steinberg GR, Foretz M, Dayon L, Morrice NA, Sakamoto K, Motif affinity and mass spectrometry proteomic approach for the discovery of cellular AMPK targets: identification of mitochondrial fission factor as a new AMPK substrate, Cell Signal 27(5) (2015) 978–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Toyama EQ, Herzig S, Courchet J, Lewis TL Jr., Loson OC, Hellberg K, Young NP, Chen H, Polleux F, Chan DC, Shaw RJ, Metabolism. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates mitochondrial fission in response to energy stress, Science 351(6270) (2016) 275–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor R, Asara JM, Fitzpatrick J, Dillin A, Viollet B, Kundu M, Hansen M, Shaw RJ, Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy, Science 331(6016) (2011) 456–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, Musi N, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Moller DE, Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action, J Clin Invest 108(8) (2001) 1167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hawley SA, Fullerton MD, Ross FA, Schertzer JD, Chevtzoff C, Walker KJ, Peggie MW, Zibrova D, Green KA, Mustard KJ, Kemp BE, Sakamoto K, Steinberg GR, Hardie DG, The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase, Science 336(6083) (2012) 918–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lee YS, Kim WS, Kim KH, Yoon MJ, Cho HJ, Shen Y, Ye JM, Lee CH, Oh WK, Kim CT, Hohnen-Behrens C, Gosby A, Kraegen EW, James DE, Kim JB, Berberine, a natural plant product, activates AMP-activated protein kinase with beneficial metabolic effects in diabetic and insulin-resistant states, Diabetes 55(8) (2006) 2256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zang M, Xu S, Maitland-Toolan KA, Zuccollo A, Hou X, Jiang B, Wierzbicki M, Verbeuren TJ, Cohen RA, Polyphenols stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase, lower lipids, and inhibit accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetic LDL receptor-deficient mice, Diabetes 55(8) (2006) 2180–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Brusq JM, Ancellin N, Grondin P, Guillard R, Martin S, Saintillan Y, Issandou M, Inhibition of lipid synthesis through activation of AMP kinase: an additional mechanism for the hypolipidemic effects of berberine, J Lipid Res 47(6) (2006) 1281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hawley SA, Ford RJ, Smith BK, Gowans GJ, Mancini SJ, Pitt RD, Day EA, Salt IP, Steinberg GR, Hardie DG, The Na+/Glucose Cotransporter Inhibitor Canagliflozin Activates AMPK by Inhibiting Mitochondrial Function and Increasing Cellular AMP Levels, Diabetes 65(9) (2016) 2784–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Villani LA, Smith BK, Marcinko K, Ford RJ, Broadfield LA, Green AE, Houde VP, Muti P, Tsakiridis T, Steinberg GR, The diabetes medication Canagliflozin reduces cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting mitochondrial complex-I supported respiration, Mol Metab 5(10) (2016) 1048–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cokorinos EC, Delmore J, Reyes AR, Albuquerque B, Kjobsted R, Jorgensen NO, Tran JL, Jatkar A, Cialdea K, Esquejo RM, Meissen J, Calabrese MF, Cordes J, Moccia R, Tess D, Salatto CT, Coskran TM, Opsahl AC, Flynn D, Blatnik M, Li W, Kindt E, Foretz M, Viollet B, Ward J, Kurumbail RG, Kalgutkar AS, Wojtaszewski JFP, Cameron KO, Miller RA, Activation of Skeletal Muscle AMPK Promotes Glucose Disposal and Glucose Lowering in Non-human Primates and Mice, Cell Metab 25(5) (2017) 1147–1159 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Salatto CT, Miller RA, Cameron KO, Cokorinos E, Reyes A, Ward J, Calabrese MF, Kurumbail RG, Rajamohan F, Kalgutkar AS, Tess DA, Shavnya A, Genung NE, Edmonds DJ, Jatkar A, Maciejewski BS, Amaro M, Gandhok H, Monetti M, Cialdea K, Bollinger E, Kreeger JM, Coskran TM, Opsahl AC, Boucher GG, Birnbaum MJ, DaSilva-Jardine P, Rolph T, Selective Activation of AMPK beta1-Containing Isoforms Improves Kidney Function in a Rat Model of Diabetic Nephropathy, J Pharmacol Exp Ther 361(2) (2017) 303311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]