Abstract

Purpose:

Malnourished adolescents with anorexia nervosa (AN) requiring medical hospitalization are at high risk for rapid reduction in skeletal quality. Even short-term bed rest can suppress normal patterns of bone turnover. We sought to determine whether low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) normalizes bone turnover among adolescents hospitalized for complications of AN.

Methods:

In this randomized, double-blind trial, we prospectively enrolled adolescent females (n=41) with AN, age 16.3 ± 1.9 years (mean ± SD) and BMI 15.6 ± 1.7 kg/m2. Participants were randomized to stand on a platform delivering LMMS (0.3g at 32–37Hz) or placebo platform for 10 minutes/day for 5 days. Serum markers of bone formation [bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP)], turnover [osteocalcin (OC)], and bone resorption [serum C-telopeptides (CTx)] were measured. From a random coefficients model, we constructed estimates and confidence intervals for all outcomes.

Results:

BSAP decreased by 2.8 % per day in the placebo arm (p=0.03), but remained stable in the LMMS group (p=0.51, pdiff=0.04). CTx did not change with placebo (p=0.56), but increased in the LMMS arm (+6.2% per day, p=0.04; pdiff=0.01). Serum OC did not change in either group (p>0.70).

Conclusions:

Bed rest during hospitalization for patients with AN is associated with a suppression of bone turnover, which may contribute to diminished bone quality. Brief, daily LMMS prevents a decline in bone turnover during bed rest in AN. Protocols prescribing strict bed rest may not be appropriate for protecting bone health for these patients. LMMS may have application for these patients in the inpatient setting.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa, mechanical stimulation, bone turnover, metabolic disorders, osteoporosis, bone formation, bone resorption, bed rest

SUMMARY

We sought to determine whether low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) normalizes bone turnover among adolescents hospitalized for AN. Brief, daily LMMS prevents the decline in bone turnover typically seen during bed rest in AN. LMMS may have application for patients with AN in the inpatient setting to protect bone health.

INTRODUCTION:

The peak bone mass achieved during adolescence is a major determinant of bone density and bone strength in adulthood1. Any condition that interferes with bone accrual during this critical time period has important long-term health implications. Anorexia nervosa (AN), a disorder characterized by restriction of energy intake, low body weight, and intense fear of gaining weight, is increasingly prevalent among adolescents2. Accompanying AN are significant changes in the normal hormonal milieu, loss of lean body mass, and prescribed restriction on weight-bearing physical activity. Skeletal deficits are seen in over half of these patients3, and often do not return to pre-illness levels even following weight restoration4,5. There is a pressing need to develop better methods to prevent bone loss and restore normal bone turnover before it becomes symptomatic or irreversible.

At highest risk for loss of bone quantity and quality may be those severely malnourished adolescents who require medical hospitalization. Current standards of care at many institutions require bed rest and relative immobilization for the duration of the hospital stay, generally 5–7 days6,7. These activity limitations are based on concerns for cardiovascular safety and a desire to maximize weight gain. However, even short-term immobilization from bed rest disrupts normal patterns of bone resorption and bone formation8,9. In a previous pilot study, we demonstrated a rapid disruption in the balance of bone turnover following 5 days of bed rest for adolescents with AN10. Markers of bone formation declined with bed rest, while bone resorption markers initially declined and then increased10. Once discharged, exercise is often prohibited or significantly restricted for extended periods of time11. In animal studies, resumption of previous mechanical loading is insufficient to stop disuse-induced bone changes12,13. Animal studies corroborate the finding that exercise plus remobilization are more effective than remobilization alone for restoring the normal bone trabecular network13.

Physical activity generally leads to increased bone mineral density (BMD), yet exercise as a strategy for bone loss in AN is avoided as it may interfere with weight restoration or cardiovascular safety. Low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) may represent a non-pharmacologic intervention capable of providing a weight-bearing stimulus to normalize bone turnover, without requiring strenuous exertion that could compromise the goals of AN treatment. Extremely low-level (<100 microstrain) high frequency (10–90Hz) strains on bone, similar to those caused by muscle contractions during postural control14, are anabolic to bone tissue in animal studies15. In humans, brief daily periods of LMMS delivered by means of a vibrating platform can stimulate biochemical markers of bone formation and/or inhibit bone loss, and preserve BMD in at-risk populations16–19.

The objective of the current study was to conduct a randomized, controlled clinical trial to determine the ability of short-term daily LMMS exposure to normalize bone turnover in adolescents hospitalized for AN. We hypothesized that LMMS would be anabolic to bone, such that adolescents with AN who were randomized to LMMS treatment would have increased bone formation markers compared to a control group of AN patients randomized to placebo treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

Subjects

From 2009–2014, 100 female adolescents were screened for study eligibility (Figure 1). Eligible patients were aged 13–21 years, ≥2 years post-menarche, and admitted to the Adolescent Medicine Service at Boston Children’s Hospital for medical complications of AN (as defined using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V). Patients were excluded for other co-morbid medical conditions (e.g., celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes mellitus) or medication use (e.g., hormonal contraceptives, glucocorticoids, anticonvulsants) known to affect bone health. No subjects regularly consumed alcohol or used cigarettes. Study procedures were approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained, with parental consent and subject assent for patients <18 years (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01100567). Forty-two patients underwent randomization; 41 completed baseline measurements and were included in the intention-to-treat analyses.

Figure 1:

Patient recruitment, enrollment, and disposition.

Study Design and Treatment

The study was a single site, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 5-day trial. After providing consent, participants were given a randomly generated study identification number. Treatment allocation (LMMS platform or a placebo platform) was randomly assigned using a list of randomly generated numbers. Only the statistician and Research Coordinator were privy to the assignments until trial completion. The PI and participants were blinded throughout the trial.

The low magnitude mechanical signals (0.3g, where 1.0g equals Earth’s gravitational field, or 9.8m/s2) were delivered using a small platform, similar in size to a bathroom scale, which produced a subtle, sinusoidal vertical translation <100 microns, as driven by a linear electromagnetic actuator. The active platform oscillates between 32–37 Hz (cycles per second), which, when combined with peak-to-peak accelerations of 0.3g, are barely perceptible. This vibration dose was chosen to maximize safety, efficacy, and compliance16,18,19. The placebo platform was identical in external appearance and emitted a high-frequency 500Hz tone, identical to the noise produced by the active platform, but did not vibrate. Under supervision of the research coordinator, participants were instructed to stand upright, in a relaxed stance, on their assigned platform for 10 minutes each day of hospitalization.

Per the eating disorder inpatient protocol at our institution, all subjects received graded nutritional therapy throughout their admission. Subjects started on a meal plan between 1,250 and 1,750 kcal/day, and advanced slowly toward their goal nutritional intake (determined on an individual basis by the hospital nutritionist who was not involved with the study). Other than when using the platform, subjects were confined to their beds throughout the day, including meal times, due to concerns of vital sign instability and the need for weight gain. No exercise or walking was permitted throughout the study period.

Data Collection

Height (cm) was measured using standardized procedure with a wall-mounted stadiometer. Weight (kg) was measured each morning, post-voiding and in the fasting state, with subjects wearing a hospital gown. Percentage ideal body weight (% IBW) was determined using the year 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Growth Charts and the formula: % IBW = 100 × [Patient BMI (kg/m2) / Median BMI for age (kg/m2)]20.

All participants responded to a semi-structured interview to obtain demographic information and health history, which included information about medication use, menstrual history, smoking, and family history of osteoporosis. Using the Youth/Adolescent Activity Questionnaire (YAAQ), a validated and reproducible measure of typical time spent over the past year in various activities and team sports21,22, subjects reported their hours/week of physical activity prior to admission, and detailed the type of exercise (e.g., walking/running, swimming, strength training). Adverse events were assessed for daily at the time of platform use.

Biochemical Assessments

Laboratory measurements began on the first morning that the participant awoke in the hospital and continued each morning until Day 5 of hospitalization. Baseline measurements occurred prior to any intervention. Venous blood was drawn between 8:30 – 10:00 am following an overnight fast. Serum samples were analyzed in the Children’s Hospital Boston Core Laboratory for concentrations of calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium (Ektachem methodology, cholesterol oxidase; Vitros, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ). Baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration was measured by chemiluminescent assay (Liason®, Diasorin, Stillwater, MN), with local inter-assay precision of 7.3%. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) was measured by a two-site chemiluminescent immunoassay (Nichols Institute); inter-assay coefficient of variation (%CV) was 5.4 – 7% for PTH. Biomarkers of bone formation [serum levels of osteocalcin (OC) and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP)] and bone resorption [serum C-telopeptides (CTx)] were measured at the Harvard Catalyst Core Laboratory (Boston, MA). OC, a bone GLA protein of bone matrix synthesized by osteoblasts, was measured by ELISA (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH; %CV 5.0–6.5%). CTx, the carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptides of Type I collagen, were measured by a commercially available immunoradiometric assay (Immunodiagnostic Systems, Tyne and Wear, United Kingdom; %CV 5.2–6.8%). BSAP was measured by access chemiluminescent immunoassay (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA; %CV 1.5–2.6%). Samples were batched to minimize chance of batch effects.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was chosen to provide 80% power to detect a 10% difference between LMMS and placebo participants in bone marker change over 5 days of hospitalization. This effect size is comparable to the measurement precision of the bone markers (CV), a lower limit of what would be considered clinically significant. To estimate the linear trend in each outcome over the course of hospitalization, we used a random-coefficients model adjusted for daily weight, age, %IBW for age, duration of AN, duration of amenorrhea, and history of fracture, with inverse probability weighting to account for the influence of missing data23. These adjustments were intended to reduce residual variance, thus increasing power to detect treatment effects, and compensate for any bias introduced by non-random dropout. From parameters of the fitted model, we constructed estimates and confidence intervals for the daily mean concentrations of biochemical markers in each arm of the trial; the mean trend within each arm; and the difference in trend between arms. BSAP showed markedly skewed distribution and was log-transformed for analysis. Trends in log BSAP were converted to % per day and multiplied by the 5-day mean to estimate the trend in concentration units. CTx and OC were analyzed on the arithmetic scale, with trends reported in concentration units and divided by the 5-day mean to estimate the trend as % per day. Computations were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Results with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

We studied 41 adolescents and young women with AN, aged 16.3 ± 1.9 yr (mean ± SD, Table 1). The majority self-reported Caucasian ethnicity. The time since last menstrual period ranged from 1–36 months, with a median of 6 months. Participants were significantly malnourished; mean BMI was 15.6 ± 1.7 kg/m2 (mean ± SD), corresponding to ideal body weight of 79 ± 11%. Prior to hospitalization, 97% of subjects (36/37 who completed the YAAQ) reported participating in physical activity, duration 21.2 ± 3.3 hr/wk. Of those engaging in physical activity, the majority were involved in weight-bearing pursuits. One-third of subjects (29%) had a positive family history of osteoporosis. Fifteen participants (37% of those responding) had sustained a fracture of the peripheral skeleton; no atraumatic fractures were reported. No fractures had occurred within the 3 months prior to the study. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the study arms (Table 1). Two patients discontinued participation. One subject randomized to placebo withdrew after baseline measurements, while one subject randomized to placebo withdrew prior to baseline assessment (Figure 1). Four placebo patients and 8 patients receiving LMMS were discharged from the hospital due to achieving medical stability prior to completing the full 5 days of study participation.

Table 1:

Baseline Participant Characteristics at Admission for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa Randomized to Either Placebo Platform (n=21) or Low-Magnitude Mechanical Stimulation (LMMS) Platform (n=20)

| All (41) | Placebo Arm (21) | LMMS Arm (20) | P * | ||

|

| |||||

| Mean ± SD | Minimum — Maximum | Mean ± SD | |||

|

|

|||||

| Age, yr | 16.3 ± 1.9 | 13 — 20 | 16.2 ± 1.8 | 16.5 ± 2.1 | 0.64 |

| Height, cm | 164.5 ± 6.3 | 150 — 178 | 165.3 ± 7.1 | 163.7 ± 5.3 | 0.43 |

| Weight, kg | 42.3 ± 5.7 | 30.1 — 51.5 | 41.3 ± 5.8 | 43.3 ± 5.7 | 0.28 |

| Fraction of IBW,% | 79.1 ± 10.9 | 52 — 103 | 77.4 ± 10.4 | 80.8 ± 11.3 | 0.33 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 15.6 ± 1.7 | 10.4 — 18.4 | 15.2 ± 1.9 | 16.1 ± 1.5 | 0.10 |

| BMI Z-score | −2.79 ± 2.2 | −13.01 — −0.52 | −3.24 ± 2.66 | −2.34 ± 1.60 | 0.20 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 34.2 ± 9.9 | 20 — 56 | 32.7 ± 9.1 | 36.1 ± 10.8 | 0.31 |

| YAAQ activity score, h/wk | 19.9 ± 12.3 | 0 – 65 | 20.3 ± 8.8 | 19.4 ± 15.4 | 0.84 |

| YAAQ inactivity score, h/wk | 40.1 ± 24.1 | 12 – 113 | 43.7 ± 24.8 | 36.1 ± 23.5 | 0.37 |

|

| |||||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | Minimum—Maximum | Median (Q1–Q3) | |||

|

|

|||||

| Time since AN diagnosis, mo | 1 (1 – 3.5) | 0 — 78 | 1 (1 – 4) | 1 (1 – 3.5) | 0.73 |

| Time since last menses, mo | 6 (4 – 9) | 1 — 36 | 6 (4 – 9) | 6 (4 – 10) | 0.58 |

|

| |||||

| N (%) | N (%) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Race: | White | 38 (93) | 20 (95) | 18 (90) | 0.74 |

| Black | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | ||

| Asian | 2 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | ||

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity: | Hispanic | 2 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 |

| Other | 39 (95) | 20 (95) | 19 (95) | ||

|

| |||||

| History of fracture: | Yes | 15 (37) | 9 (43) | 6 (30) | 0.52 |

| No | 26 (63) | 12 (57) | 14 (70) | ||

|

| |||||

| Family history of osteoporosis | Yes | 12 (29) | 4 (19) | 8 (40) | 0.35 |

| No | 23 (56) | 13 (62) | 10 (50) | ||

| Unknown | 6 (15) | 4 (19) | 2 (10) | ||

Student t, Wilcoxon rank-sum, or Fisher Exact test comparing distribution in LMMS and placebo arms.

LMMS, low magnitude mechanical stimulation; IBW, ideal body weight; BMI, body mass index; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxy-vitamin D; YAAQ, Youth/Adolescent Activity Questionnaire; AN, anorexia nervosa.

Biochemical Data and Weight Restoration

Almost all subjects maintained calcium levels within the normal range (8.4–10.5 mg/dL). One subject developed transient hypocalcemia (serum calcium 8.0 mg/dL); this abnormality resolved without intervention. All participants received routine daily oral phosphorus supplementation (potassium phosphate and sodium phosphate 250 mg orally BID to 500 mg orally TID); random coefficients analysis showed no trends in phosphorus levels. Baseline PTH was 25.0 ± 10.7 pg/mL (normal range 10–65 pg/mL). Low vitamin D concentrations were prevalent. Sixteen subjects (44% of available baseline values) had 25(OH)D concentrations < 30 ng/mL [25(OH)D range 20–56 ng/mL]; no subject was vitamin D deficient [25(OH)D<20 ng/mL]. Each participant received a daily multivitamin containing 400 IU of vitamin D.

All subjects gained a clinically significant amount of weight over the course of the study. Mean weight increased at a rate of 0.45 ± 0.03 kg/day (p<0.0001, regression trend ± SE adjusted for baseline covariates), leading to an increase in both weight and BMI by the time of discharge. Girls in the LMMS arm gained slightly less weight on average (0.38 ± 0.04 kg/day) than did those randomized to the placebo platform (0.51 ± 0.04 kg/day, p=0.04). Consequently, all analyses were adjusted for daily weight to rule out weight gain as a mediator of the effect between platform use and our outcome measures. Both groups met clinical weight gain goals (0.2 kg per day) and length of hospitalization was not impacted by study participation.

Bone Turnover Markers

Participants who were assigned to use the LMMS platform daily maintained a stable concentration of serum BSAP throughout the trial (Table 2; Day 1 mean 10.3 μg/L versus Day 5 mean 10.1 μg/L, p=0.51). In contrast, in patients using the placebo platform, BSAP steadily declined by an average of −2.8% per day (Table 2; p=0.03) between Day 1 (13.7 μg/L) and Day 5 (12.3 μg/L). Figure 2 illustrates the significant difference in 5-day trend between the two trial arms (2.2% per day, Pdiff=0.04).

Table 2.

Bone turnover marker concentrations and trends over a 5-day hospitalization in 41 adolescents and young women with anorexia nervosa, after random assignment to low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) or placebo platform.*

| Bone marker | Platform | Day 1 mean | Day 5 mean | Five-day trend |

Ptrend | Pdiff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/L or ng/mL per day | % perday | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| BSAP, μg/L | LMMS | 10.3 (7.9, 13.4) | 10.1 (7.7, 13.1) | −0.07 (−0.26, 0.14) | −0.6 (−2.6, 1.3) | 0.51 | 0.04 |

| Placebo | 13.7 (10.7, 17.7) | 12.3 (9.5, 15.9) | −0.36 (−0.68, −0.04) | −2.8 (−5.2, −0.3) | 0.03 | ||

|

| |||||||

| CTx, ng/mL | LMMS | 1.17 (0.90, 1.43) | 1.50 (1.22, 1.77) | +0.083 (0.006, 0.159) | +6.2 (0.4, 12.0) | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Placebo | 1.44 (1.19, 1.70) | 1.34 (1.01, 1.66) | −0.027 (−0.119, 0.065) | −1.9 (−8.5, 4.7) | 0.56 | ||

|

| |||||||

| OC, ng/mL | LMMS | 13.1 (7.0, 19.2) | 13.6 (6.9, 20.2) | 0.12 (−1.06, 1.30) | 0.9 (−7.9, 9.7) | 0.99 | 0.91 |

| Placebo | 16.7 (11.3, 22.1) | 17.7 (11.2, 24.3) | 0.26 (−1.12, 1.64) | 1.5 (−6.5, 9.5) | 0.90 | ||

BSAP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase. CTx, C-telopeptides. OC, osteocalcin.

Means and trend with 95% confidence interval, from fitted random-coefficients model adjusted for daily weight, age, percentage median body weight for age, duration of anorexia, duration of amenorrhea, and history of fracture. Ptrend tests for significant (non-zero) mean slope within trial arm. Pdiff tests for difference in mean slope between arms.

Figure 2:

Raw data and trends in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP), a marker of bone formation, in 41 adolescent females with anorexia nervosa randomized to 5 days of intervention with low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS, left graph) or placebo (right graph). The “x’s” represent the raw data for each subject. The solid black line represents the mean trend over time from a fitted random-coefficients model, adjusted for time-varying weight, age, percentage of median body weight for age, duration of anorexia nervosa, duration of amenorrhea, and history of fracture. The shaded gray areas represent the 95% confidence band for the mean trend.

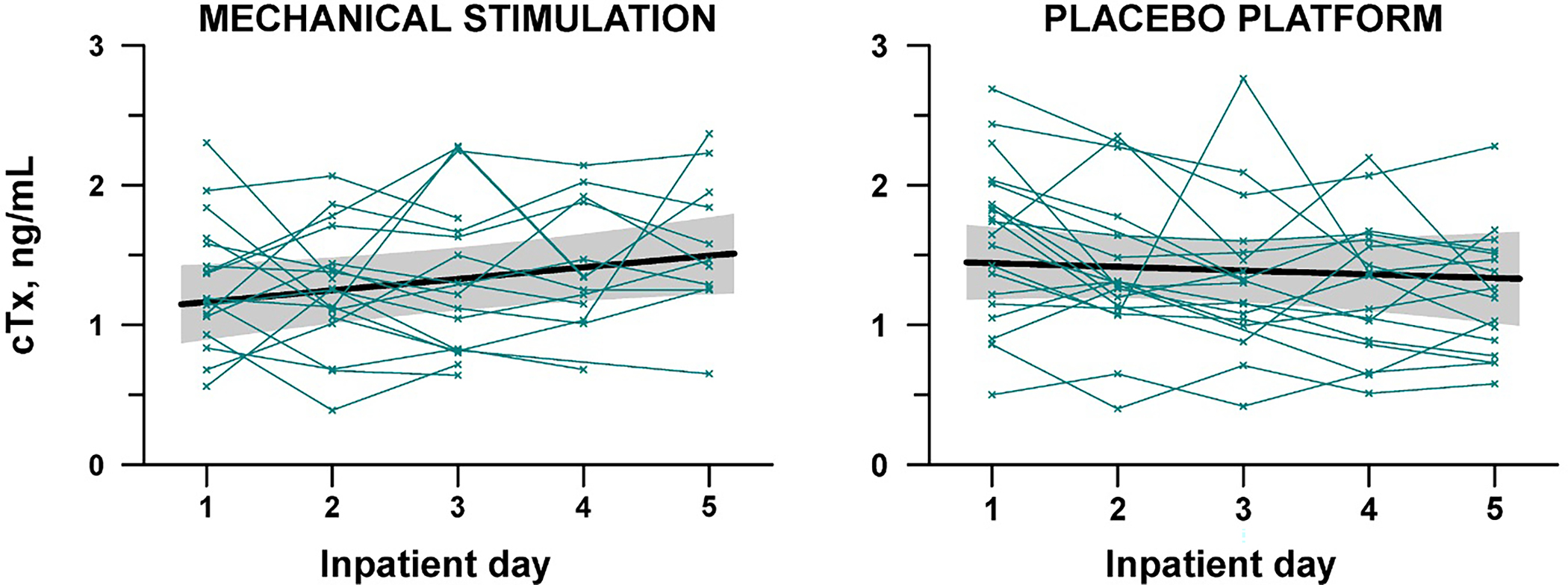

Serum CTx rose in the LMMS group between Day 1 (1.17 ng/mL) and Day 5 (1.50 ng/mL), for an average increase of +6.2% per day (Table 2 and Figure 3; p=0.04). In the placebo arm, serum CTx did not change over the 5 days (p=0.56) leading to a significant difference in 5-day trend between the groups (4.3% per day, pdiff=0.01).

Figure 3:

Raw data and trends in C-telopeptides (CTx), a marker of bone resorption, in 41 adolescent females with anorexia nervosa randomized to 5 days of intervention with low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) or placebo. The “x’s” represent the raw data for each subject. The solid black line represents the mean trend over time from a fitted random-coefficients model, adjusted for time-varying weight, age, percentage of median body weight for age, duration of anorexia nervosa, duration of amenorrhea, and history of fracture. The shaded gray areas represent the 95% confidence band for the mean trend.

Serum OC did not change in either group over the course of the study (Table 2; p≥0.90). Controlling for daily weight as well as the baseline covariates had negligible influence on the trend estimates, indicating that weight gain during hospitalization did not account for the bone marker changes.

DISCUSSION:

In this randomized trial, we observed that brief, daily use of a low-magnitude mechanical stimulation platform during 5 days of hospitalization for malnourished adolescents with AN led to stabilization in markers of bone formation (BSAP) without adverse events or clinically significant effects on weight restoration. In contrast, users of a placebo platform exhibited a significant decrease in bone formation markers, similar to what we previously reported in our study of bed rest10. Patients with AN are recognized to have depressed bone formation and higher bone resorption24. Our highly-specific bone biomarker data reflect that with bed rest, bone formation was lower10. In contrast, with LMMS bone formation remained stable.

Healthy adolescents have increased bone turnover, with elevated bone formation and bone resorption markers that accompany growth and pubertal development25. Adolescents with AN have lower levels of bone formation and resorption markers than normal-weight control subjects26, suggesting that bone turnover is suppressed in AN. Without bone turnover, bone cannot increase in mass nor repair itself. The additive effect of even short-term immobilization may exacerbate the bone insults for an adolescent with AN. Skeletal unloading reduces the mechanical forces applied to bones, compromises bone quality, and elevates fracture risk. During even transient immobilization, bone resorption and formation are uncoupled12,27. In our earlier observational study, BSAP consistently decreased during 5 days of bed rest. In contrast, urinary N-telopeptides (a marker of bone resorption) initially declined, but then increased after Day 3 of immobility10. A priori, we anticipated that LMMS would increase markers of bone formation and suppress bone resorption. Instead, LMMS maintained markers of bone formation, but led to slight increases in markers of bone resorption. This observed pattern mirrors normal adolescent increases in bone turnover25.

These results offer insights into bone turnover in the setting of severe malnutrition, refeeding, and limited mobility in AN. If AN suppresses cortical modeling, older bone with greater material density and mineralization will accumulate, leading to greater cortical volumetric BMD28,29. While bone in this setting may be denser, it is not necessarily stronger. Excessive bone mineralization leads to brittle bones30 and increased fracture risk31. As such, the increase in bone turnover observed with LMMS in the current study may be beneficial to the skeleton. Participants receiving placebo also demonstrated differing patterns of bone turnover from our original investigation.10 BSAP steadily decreased over the 5 days of hospitalization, while CTx did not significantly change; this result may be an effect of standing up for 10 minutes daily, but requires further study.

A common perception is that the mechanical load must be robust to increase bone quantity and quality. However, extremely low-level strains on bone, similar to those caused by muscle contractions during postural control, are anabolic to bone tissue. High frequency LMMS delivered via vibrating platform can inhibit bone loss and preserve BMD in at-risk populations16,18,32 In a 6-month trial, children with cerebral palsy exposed to LMMS showed +6.3% increases in tibial vBMD from baseline; children who stood on placebo devices had a 11.9% decline18. In adolescents with existing low BMD and a history of fracture33, subjects receiving LMMS for at least 2 minutes/day had increased spinal trabecular vBMD (+3.9%) compared to control subjects and poor compliers. A similar study performed in persons of advanced age (mean 83y) yielded disappointing results; changes in total femoral trabecular vBMD and mid-vertebral trabecular vBMD did not differ between LMMS and placebo groups after 24 months34. Reasons for the lack of efficacy may include a lack of mechanical sensitivity/responsiveness of resident bone cells in the elderly skeleton, or a reduced number of available progenitors in the bone marrow. In animal studies, LMMS can bias fate selection of bone progenitors, driving them towards osteoblasts rather than adipocytes35. This effect may be the mechanism of the beneficial effect of LMMS in AN, since these patients exhibit premature conversion of hematopoietic to fat cells in the marrow of the peripheral skeleton, and potentially have adipocyte over osteoblast differentiation in the stem cell pool36. These hypotheses highlight the importance of early intervention for patients while the skeleton is still responsive.

Study limitations deserve acknowledgement and consideration. Data regarding patterns of bone turnover prior to hospitalization are not available. Full bone turnover marker data were not available for 14 subjects in the study due to changes in clinical course of treatment (e.g., transfer to inpatient psychiatry ward or early medical discharge). However, completers did not differ from those with incomplete data with regard to baseline characteristics. If all participants had been retained until end of study, the differences between groups may have even been greater than we observed. Large increases in nutrient intake occurred during the study, leading to significant weight gain. While girls receiving LMMS therapy gained slightly less average weight per day than girls in the placebo group, both groups met expected goal rates of weight restoration and the hospital course was not impacted. As all subjects were ≥2 years post-menarche; results may not be generalizable to pre-menarchal girls. Although current bone biomarkers are more accurate and precise compared to earlier assays, the variability of these markers should still be acknowledged, as well as the fact that these biomarkers represent surrogate markers of physiologic processes with their inherent limitations. The duration of exposure to bed rest and to the LMMS intervention was brief. The length of the study was determined by the average clinical length of stay for medical admissions for anorexia nervosa at our institution. As discussed above, other trials conducted in human subjects have been of much longer duration (6 or 12 months). Longer exposure to the LMMS intervention would be required to demonstrate an effect on less dynamic measures of skeletal health, such as bone density, bone geometry, or fracture risk. The results of this pilot study should be confirmed by a randomized, controlled trial of longer duration to determine whether bone density and quality can be restored, and to explore metabolic outcomes. Lastly, we were not able to conduct follow-up assessments of study subjects.

In summary, low bone mass is a widespread, chronic source of morbidity for adolescents and young women with AN. These patients have numerous risk factors for skeletal deficits, including low body weight, poor nutritional intake, and hormonal deficits. In addition, in an effort to promote weight gain, activity restrictions are commonly imposed. To date, pharmacologic treatments aimed at preventing or ameliorating bone loss in AN have been met with variable results, and are not without side effects. The young age of these patients compounds the inherent risks of a treatment strategy, based on long-term commitment to bone-specific agents. Our preliminary data show that LMMS is safe and may help to promote bone health during the acute inpatient setting, and prevent the deleterious suppression of bone turnover previously observed with bed rest. While it remains unclear whether this restoration of bone turnover will ultimately benefit the skeletal phenotype, there is evidence that musculoskeletal health can improve in adolescents with such signals, and without serious adverse events. LMMS signals may represent a strategy to prevent and/or treat low bone mass in adolescents with AN: a safe, non-invasive, non-pharmacologic means to enhance both bone density and bone quality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We gratefully acknowledge our patients and their families; the expert nursing care at Boston Children’s Hospital; and contributions of the Boston Children’s Hospital Core Laboratory. Supported by NICHD K23 HD060066, NICHD T32 HD043034, NIA R01 AG25489, NIAMS R01 AR060829, NIH UL1 RR-025758 (Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center), and the Boston Children’s Hospital Department of Medicine and Clinical and Translational Study Unit (CTSU). CTR is a founder of Marodyne Medical, and has been issued several patents around the use of mechanical signal influence on bone quality. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: Dr. Clinton Rubin is a founder of Marodyne Medical, and has been issued several patents around the use of mechanical signal influence on bone quality. The other authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest. Study sponsors had no role in: (1) study design; (2) the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; (3) the writing of the report; or (4) the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Dr. DiVasta wrote the first draft of the manuscript. No author was given any honorarium, grant, or other form of payment to produce the manuscript. Each author listed on the manuscript has seen and approved the submission of this version of the manuscript and takes full responsibility for the manuscript.

Clinical Trials registration: clinicaltrials.gov NCT01100567

References:

- 1.Eastell R Pathogenesis of postmenopausal osteoporosis. In: Favus MJ, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. Fifth Ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; 2003:314–316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman SF, McKenzie N, Hehn R, et al. Predictors of outcome at 1 year in adolescents with DSM-5 restrictive eating disorders: report of the national eating disorders quality improvement collaborative. J. Adolesc. Health 2014;55(6):750–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon CM. Effects of Oral Dehydroepiandrosterone on Bone Density in Young Women with Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87(11):4935–4941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golden NH. Eating disorders in adolescence: what is the role of hormone replacement therapy? Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;19(5):434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachrach LK, Guido D, Katzman D, Litt IF, Marcus R. Decreased bone density in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics 1990;86(3):440–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz BI, Mansbach JM, Marion JG, Katzman DK, Forman SF. Variations in admission practices for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a North American sample. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2008;43(5):425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sylvester CJ, Forman SF. Clinical practice guidelines for treating restrictive eating disorder patients during medical hospitalization. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2008;20(4):390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Wiel HE, Lips P, Nauta J, Netelenbos JC, Hazenberg GJ. Biochemical parameters of bone turnover during ten days of bed rest and subsequent mobilization. Bone Miner. 1991;13(2):123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heer M, Baecker N, Mika C, Boese A, Gerzer R. Immobilization induces a very rapid increase in osteoclast activity. Acta Astronaut 2005;57(1):31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiVasta AD, Feldman HA, Quach AE, Balestrino M, Gordon CM. The effect of bed rest on bone turnover in young women hospitalized for anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94(5):1650–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzog DB, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, et al. Recovery and relapse in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a 7.5-year follow-up study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999;38(7):829–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trebacz H Disuse-induced deterioration of bone strength is not stopped after free remobilization in young adult rats. J. Biomech. 2001;34(12):1631–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kannus P, Sievanen H, Jarvinen TL, et al. Effects of free mobilization and low- to high-intensity treadmill running on the immobilization-induced bone loss in rats. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1994;9(10):1613–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang RP, Rubin CT, McLeod KJ. Changes in postural muscle dynamics as a function of age. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1999;54(8):B352–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin C, Turner AS, Bain S, Mallinckrodt C, McLeod K. Anabolism. Low mechanical signals strengthen long bones. Nature 2001;412(6847):603–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilsanz V, Wren TA, Sanchez M, Dorey F, Judex S, Rubin C. Low-level, high-frequency mechanical signals enhance musculoskeletal development of young women with low BMD. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21(9):1464–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin C, Xu G, Judex S. The anabolic activity of bone tissue, suppressed by disuse, is normalized by brief exposure to extremely low-magnitude mechanical stimuli. FASEB J. 2001;15(12):2225–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward K, Alsop C, Caulton J, Rubin C, Adams J, Mughal Z. Low magnitude mechanical loading is osteogenic in children with disabling conditions. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19(3):360–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin C, Recker R, Cullen D, Ryaby J, McCabe J, McLeod K. Prevention of postmenopausal bone loss by a low-magnitude, high-frequency mechanical stimuli: a clinical trial assessing compliance, efficacy, and safety. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19(3):343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv. Data 2000;(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW, Field AE, et al. Comparing physical activity questionnaires for youth: seasonal vs annual format. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001;20(4):282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Frazier AL, Colditz GA, Gillman MW. The influence of wanting to look like media figures on adolescent physical activity. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2004;35(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2013;22(3):278–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maïmoun L, Guillaume S, Lefebvre P, et al. Evidence of a link between resting energy expenditure and bone remodelling, glucose homeostasis and adipokine variations in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Osteoporos. Int. 2016;27(1):135–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mora S, Pitukcheewanont P, Kaufman FR, Nelson JC, Gilsanz V. Biochemical markers of bone turnover and the volume and the density of bone in children at different stages of sexual development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999;14(10):1664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misra M, Miller KK, Cord J, et al. Relationships between serum adipokines, insulin levels, and bone density in girls with anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92(6):2046–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doty SB, DiCarlo EF. Pathophysiology of immobilization osteoporosis. Curr Opin Orthop 1995;6(5):45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Divasta AD, Feldman HA, O’Donnell JM, Long J, Leonard MB, Gordon CM. Skeletal Outcomes by Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography and Dual-energy X-ray Absorpotiometry in Adolescent Girls with Anorexia Nervosa. Osteoporos. Int. 2016:Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wetzsteon RJ, Shults J, Zemel BS, et al. Divergent effects of glucocorticoids on cortical and trabecular compartment BMD in childhood nephrotic syndrome. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2009;24(3):503–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boskey AL, DiCarlo E, Paschalis E, West P, Mendelsohn R. Comparison of mineral quality and quantity in iliac crest biopsies from high- and low-turnover osteoporosis: an FT-IR microspectroscopic investigation. Osteoporos. Int. 2005;16(12):2031–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davison KS, Siminoski K, Adachi JD, et al. Bone strength: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36(1):22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin C, Judex S, Qin YX. Low-level mechanical signals and their potential as a non-pharmacological intervention for osteoporosis. Age Ageing 2006;35 Suppl 2:ii32–ii36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilsanz V, Sanchez M, Dorey F, Judex S, Rubin C. Low-Level, High-Frequency Mechanical Signals Enhance Musculoskeletal Development of Young Women With Low BMD. 2006;21(9):1464–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiel DP, Hannan MT, Barton BA, et al. Low-Magnitude Mechanical Stimulation to Improve Bone Density in Persons of Advanced Age: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015;30(7):1319–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubin CT, Capilla E, Luu YK, et al. Adipogenesis is inhibited by brief, daily exposure to high-frequency, extremely low-magnitude mechanical signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(45):17879–17884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ecklund K, Vajapeyam S, Feldman HA, et al. Bone marrow changes in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25(2):298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]