Abstract

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide accounting about 85% of total lung cancer cases. The receptor REarranged during Transfection (RET) plays an important role by ligand independent activation of kinase domain resulting in carcinogenesis. Presently, the treatment for RET driven NSCLC is limited to multiple kinase inhibitors. This situation necessitates the discovery of novel and potent RET specific inhibitors. Thus, we employed high throughput screening strategy to repurpose FDA approved compounds from DrugBank comprising of 2509 molecules. It is worth noting that the initial screening is accomplished with the aid of in-house machine learning model built using IC50 values corresponding to 2854 compounds obtained from BindingDB repository. A total of 497 compounds (19%) were predicted as actives by our generated model. Subsequent in silico validation process such as molecular docking, MMGBSA and density function theory analysis resulted in identification of two lead compounds named DB09313 and DB00471. The simulation study highlights the potency of DB00471 (Montelukast) as potential RET inhibitor among the investigated compounds. In the end, the half-minimal inhibitory activity of montelukast was also predicted against RET protein expressing LC-2/ad cell lines demonstrated significant anticancer activity. Collective analysis from our study highlights that montelukast could be a promising candidate for the management of RET specific NSCLC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12032-022-01924-4.

Keywords: Machine-learning classifiers, Extra precision docking, DFT analysis, Molecular dynamics, Inhibitory activity prediction

Introduction

RET encodes the receptor tyrosine kinase located in chromosome 10 and is responsible for the development of renal, neural and neuroendocrine tissues during embryogenesis [1]. The alterations to RET enhance constitutive and ligand-independent activation of kinase domain, which in turn triggers carcinogenesis. Till date, two primary mechanism of RET alterations have been reported: (i) point mutations and (ii) chromosomal rearrangements. RET point mutations occur in cysteine residues resulting in aberrant dimerization and persistent activation of the kinase domain (e.g., C634R/W, C620R). Notably, on sequencing more than 10,000 distinct metastatic tumours, RET mutations have been discovered in 2.4% of all cases, especially in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and thyroid cancer [2]. Alternatively, RET rearrangement causes constitutive activation of the receptor by forming a fusion protein that encompasses of RET kinase domain and dimerized domain of the other fusion partners. Remarkably, RET fusions are observed in NSCLC (1–2%), papillary thyroid cancer (10–20%) and in other cancer subtypes such as breast and colorectal cancer [3]. Despite the low percentage of RET involvement in cancers, inhibition of RET protein is of immense importance to overcome the cancer burden reported each year globally.

The current landscape of treating RET positive NSCLC patients include multiple kinase inhibitors (MKIs) and RET specific inhibitors. MKIs such as vandetanib and cabozantinib provided the first glimmer of hope for treating NSCLC patients harbouring RET alterations. However, the incidence of secondary effects by MKIs includes hypertension, constipation, neutropenia and fatigue, necessitates the development of alternative drug molecules [4]. Hence RET specific inhibitors pralsetinib and selpercatinib were developed to remedied the limitations of MKIs. Nevertheless, the emergence of acquired drug resistance against RET specific inhibitors due to the development of gatekeeper (V804M/L) and solvent front secondary mutations (G810A/C/R/S) have been reported in the recent times [5]. Although an adequate number of clinical trials were carried out to offset the debility of the specific inhibitors, the adverse off-target side effects and limited response durability limited its efficacy [6]. Therefore, developing novel RET kinase inhibitors is imperative to circumvent the aforementioned limitations.

Virtual Screening is a frequently used computational method in the drug discovery pipeline. Previous literature evidences have reported identification of many small molecule and natural compound-based inhibitors against RET protein including 3-amino-4-anilinothieno[2, 3-b] pyridine-2-carboxamide, 2-{2-[(3, 5-dimethylphenyl)amino]pyrimidin-4-yl}-N-[(1S)-2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl]-4-methyl-1, 3-thiazole-5-carboxamide and N-[2-(3, 4-dimethoxyphenyl)ethyl]-4-(4-oxo-1, 4-dihydro-2-quinazolinyl)butanamide using different pharmacophoric and virtual screening strategies [7–9]. Moreover, enormous number of newer compounds is discovered recently, which have been archived and disseminated to the scientific community through various databases. Hence, high precision screening is still desperately needed to explore larger chemical spaces resulting in identification of structurally diverse compounds with high efficacy.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) has become advantageous in assisting researchers to identify potential candidates for clinical trials. For instance, novel compounds against Alzheimer, COVID-19, Candida albicans infection and cancer were identified by ML based virtual screening strategy [10–13]. In another instance, inhibitors against cytochrome P450, LasR, DDP-4, EGFR, HSP90, FXa and CDK2 were successfully identified by scrutinizing large databases using ML and docking techniques [14–17]. These evidences portray that ML models in virtual screening pipeline assisted the researchers to tackle the intricate problems of screening an effective compound [18]. Thus, we employed ML algorithm alongside traditional high throughput screening to identify potent repurposed candidate for RET specific NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Dataset curation

A set of 9914 compounds tested against RET protein was retrieved from BindingDB database (https://www.bindingdb.org/) for ML model development [19]. The compounds without IC50 value and the duplicates were removed by manual inspection. With an aim of developing robust predictive ML models, the IC50 of these molecules were converted into their corresponding pIC50 values. These compounds were further stratified into actives and inactives based on the reported activity of vandetanib (pIC50 = 7.3), as it is the widely used primary MKI to treat RET positive NSCLC in patients. Moreover, vandetanib was considered as a reference compound due to its modest activity, high selectivity and efficacy [20, 21]. This yielded a dataset of 2854 compounds containing equal number of actives and inactives was curated for further processing.

Descriptor generation and dataset pruning

Molecular descriptors are the physiochemical properties calculated using rational method that transform the chemical information represented by molecular symbols into meaningful data. Initially, ChemSAR standardization tool was employed for optimization of the chemical structures. It involves sanitization, disconnecting metals, application of normalization rules, reionization of acids and recalculating stereochemistry of the compounds [22]. Subsequently, PaDEL descriptor was employed for the generation of fingerprints (FPs) and descriptors of all compounds considered in this study [23]. A total of 5358 features comprising of 2-D descriptors (1444), 3-D descriptors (431) and molecular FPs such as CDK FP, extended FP, estate FP, MACCS FP, PubChem FP and Substructure FP were computed. The dataset was then preprocessed using statistical parameters like variance and correlation to eliminate irrelevant features. The preprocessing of the generated dataset was executed according to the procedure reported in our recent publication [24].

Construction and evaluation of machine-learning classifiers

Recursive feature elimination with cross-validation (RFECV) had gained immense attention for feature selection in the field of classifying biochemicals due to its high precision [14, 23]. RFECV identifies important descriptors based on the level of correlation calculated between the variables and the target [25]. Henceforth, the highly important features were used for further ML model generation.

ML models including logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), naïve Bayes (NB), gradient boosting (GB), decision tree (DT) and neural network (NN) demonstrates high speed, accuracy and have been widely employed in classification modelling [26]. LR maps the dependent and independent variables to estimate the probability threshold using the sigmoid function. RF model is developed based on large number of trees created during the random seed split. This approach creates trees at random to avoid data overfitting, which is then combined by the RF classifier to produce a single, more accurate model [27]. The key attributes are identified and categorized into binary outcomes using the Gini score and mean decrease accuracy. DT involves mapping of interactions between nodes and leaves. The objects are depicted as nodes whereas the object value is represented as leaf. Due to its widespread application in data prediction, data analysis, and datamining, DT has become beneficial. The NB technique is a quick and easy classifier that relies on the Bayes theorem. By removing the marginal probabilities calculated based on the particular criteria, the aforementioned technique is applied to learn the likelihood of fitting to each subgroup. GB machine, a collective and non-parametric method, combines the predictions of unreliable learners to provide more reliable results than a single learner. GBM employs additive expansion for model improvements, which gives researchers more latitude than other parametric ML models. The most popular approach for tackling classification and regression issues is the SVM. By employing a structural risk reduction method during model development, SVM reduces overfitting. Instead of reducing a model's mean square error, this approach lowers the generalization error [27]. Additionally, it sorts the input data into categories using both linear and non-linear hyperplanes. NNs accomplish modelling by learning from data with known outcomes and optimising weights for improved prediction in scenarios with unknown outcomes. Thus, the above-mentioned models were chosen for model construction in the current investigation.

The detailed information on packages and the tuning parameters of the generated models are consolidated in Table S1. The train_test_split sub-package of sklearn.model_selection was used to stratify the dataset as training set and test set in the ratio of 8:2 respectively. Of note, three tiers of validation set such as test set, 5-fold cross validation, 10-fold cross validation and external validation set were employed in this study to ensure the performance and generalization capability of the models. These models were evaluated using five different performance metrices such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score and receiver operating curve (ROC). The ML model with high accuracy and F1 score was further considered for screening the FDA approved subset of DrugBank database containing 2509 compounds (https://go.drugbank.com/) [28]. Python 3.7.6 was used to execute all the analyses in the Jupyter Notebook platform.

Molecular docking

The X-ray crystallographic structure of RET protein (PDB ID 2IVU) was downloaded from Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). This crystallized structure was found to possess wild RET protein complexed with vandetanib in its phosphorylated state. It is to be noted that high catalytic activity of the tyrosine kinase domain is promoted by the phosphorylated basal state of A-loop through modulating cis-autoinhibition. On the other hand, the non-phosphorylated condition causes the A-loop conformation to conflict with the binding sites of the substrate. Hence, to provide high precision results, the phosphorylated RET receptor was chosen for the study [29].

Subsequently, the retrieved structure was prepared and optimized using Protein Preparation Wizard module of Schrödinger suite [30]. Protein structure was protonated and minimized using OPLS_2005 force field. This process involves insertion of missing atoms, modelling of loops and removal of co-crystallized water [8]. On the other hand, LigPrep module was employed to optimize the ligand molecules which includes ionization and computation of stereoisomers of the compound. Consequently, grid-based extra precision docking strategy using Glide module was chosen to carry out molecular docking process due to its high accuracy and reproducibility [31]. Finally, the important pharmacokinetic properties, interaction pattern, toxicity and half-life period of the compounds were examined using QikProp module of Schrödinger, ProTox-II server and ADMET lab 2.0 server, respectively [32–34].

Rescoring and post docking validation

RF score

The rescoring function of binding affinity between the ligands and RET was accomplished using random forest score (RF score) (https://github.com/oddt/rfscorevs). In this technique, the RF score was calculated by correlating structural description of the complex at atomic level with its binding affinity [35]. Higher the RF score indicates the better binding of the ligand into the binding pocket of the protein.

Binding free energy estimation using MM-GBSA

Additionally, the binding free energy of protein–ligand complexes were estimated using Prime module of Schrödinger suite. The H-bonds, self-contact interactions, π–π interaction and hydrophobic interactions in the docked complexes were optimized using VSGB 2.0 solvation model. The contribution of different energy terms to binding free energy was also investigated during the analysis. The overall binding free energy was determined using the following equation:

where ΔG (Binding free energy), E (protein–ligand complex), E (protein), and E (ligand) indicates the total binding free energy, energy of the complex and the energy of unbound protein, ligand, respectively.

DFT analysis

Similarly, the density function theory analysis of the lead molecules was carried out as per the protocol reported in our recent publication [5]. In this study, the global descriptors such as energy gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), hardness, softness, ionization potential, electron affinity and chemical potential were estimated to screen the hit molecules. The parameters were determined using the following equation:

Molecular dynamics

In the present study, GROMACS 5.1.2 framework is employed to investigate the behaviour of the docked complexes using GROMOS96 54a7 force field [36]. Initially, the RET protein was simulated in a water filled dodecahedron box of size 10 Å and the topology parameters of the ligands were generated using PRODRG server. The linear constraint solver algorithm and Partial Mesh Ewald method were employed to compute electrostatic energy calculation and covalent bond constraints. Further, the charges of the complex system were neutralised using single point charge waters and eight chlorine counter ions. Later, the system was laid back by an energy minimization method using steepest decent approach. Subsequently, the position of the system was restrained during NPT phase (Number of particles, pressure, temperature) and NVT phase (Number of particles, volume and temperature) with temperature and pressure of 298 K and 1 bar using Berendsen coupling and Parrinello–Rahman algorithm. Finally, 100 ns dynamic simulation with an integration time step of 2 fs. The root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), hydrogen bond (H-bonds), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), radius of gyration (Rg), principal component analysis or essential dynamics and free energy landscape (FEL) of the apoprotein and protein–ligand complexes were evaluated using the various utilities of GROMACS. Towards the end of the analysis, the output files of the trajectories were visualized with the aid of xmgrace.

Inhibitory activity prediction

Prediction of anticancer compound sensitivity with multimodal attention-based NNs (PaccMann) server (https://ibm.biz/paccmann-aas) was employed in the present study to determine the inhibitory activity of the compounds against various cell lines [37]. It is an open access server that estimates drug sensitivity in terms of half-maximal inhibitory concentration using multimodal deep learning models built by integrating SMILES sequence of the compound, gene expression profiles and prior knowledge on protein–protein interactions. Based on the IC50 values obtained at the end of the prediction process, lead identification and drug repurposing regimes were carried out.

Results and discussion

Dataset curation and feature selection

A total of 2854 compounds comprising in vitro activity data against RET protein were curated from the BindingDB repository for ML model development. Initially, these molecules along with external validation dataset were standardized using ChemSAR standardization toolkit. All the compounds were found to possess satisfactory stereochemical properties.

Notably, about 5358 features including 1875 molecular descriptors and 3483 bits of FPs were generated for each compound using PaDEL Descriptor. The average molecular weight of the compounds in training set varied between 6.195 and 12.368 g/mol indicating the drug likeliness of the compounds. While, the average molecular weight in the external test set varied between 7.632 and 12.335 g/mol. This depicts that both the training set and external validation set shared a similar chemical feature. Thus, the chemical space of external validation dataset lies within the scope of the training set.

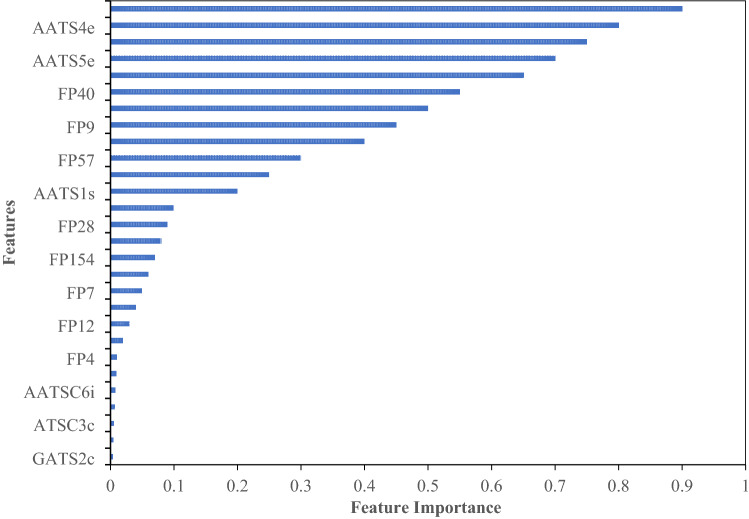

To enhance the prediction abilities of the ML models, highly pertinent features were filtered out using feature extraction technique. Primarily, around 1321 features with a sum of zero were removed from the dataset. Later, 1061 features with variance less than 0.01 and 2919 features with correlation greater than 0.99 were removed during the study to prevent redundancy. Ultimately after pre-processing, 56 features containing 30 descriptors and 26 FPs were identified. Finally, the RFECV strategy was implemented to identify highly significant and relevant features. A subset of 29 features were chosen based on the RFE scoring function for further processing and model generation. It is evident from Fig. S1 that the selected 29 features have the probability of achieving predictive accuracy of 0.95 during 10-fold cross validation. Similarly, variable importance plot of the features selected using RFECV was also estimated and the results are demonstrated in Fig. 1. From the image, it is obvious that the descriptors MATS1c, AATS4e and ATSC0c were identified as highly important while GATS2c, AATS6e, ATSC3c and FP27 found to be least important among the selected features. It is certain that ML model built with these resultant features would discriminate the actives from inactive molecules with high precision.

Fig. 1.

Variable importance plot of RET features selected using RFECV

Performance evaluation of machine learning models

Seven ML classifiers were generated using the selected molecular descriptors and FPs in the current investigation. Herein, the parameter tuning process of the ML models were executed using grid search 10-fold cross validation method. The models prior and after parameter tuning were evaluated using different performance metrices and the results are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance metrices of machine learning models prior and after parameter tuning

| S. No | Machine-learning models | Prior parameter tuning | After parameter tuning | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 score | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 score | ||

| 1 | Logistic regression | 0.652 | 0.622 | 0.758 | 0.683 | 0.908 | 0.906 | 0.913 | 0.91 |

| 2 | Random forest | 0.649 | 0.637 | 0.72 | 0.676 | 0.889 | 0.894 | 0.885 | 0.89 |

| 3 | Support vector machine | 0.668 | 0.607 | 0.809 | 0.694 | 0.912 | 0.913 | 0.914 | 0.913 |

| 4 | Naïve Bayes | 0.517 | 0.508 | 0.926 | 0.656 | 0.909 | 0.91 | 0.911 | 0.91 |

| 5 | Gradient boosting | 0.638 | 0.651 | 0.739 | 0.692 | 0.902 | 0.903 | 0.903 | 0.903 |

| 6 | Decision tree | 0.642 | 0.605 | 0.669 | 0.635 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.765 |

| 7 | Neural network | 0.656 | 0.612 | 0.718 | 0.66 | 0.872 | 0.859 | 0.892 | 0.876 |

It is evident from the Table 1 that the accuracy of models prior to parameter tuning ranged from 0.517 to 0.668. Notably, SVM achieved the highest accuracy while NB achieved the least accuracy during our analysis. In general, precision and recall indicate the capability of the models to classify the cases into true positive and negative, respectively. Higher values of these performance metrices indicates the classifying capability and reliability of the models [38]. In the present study, the precision and recall score of the ML models ranged from 0.508 to 0.651 and 0.669 to 0.926, respectively. Moreover, scientific evidences suggest that F1 score is found to be a crucial parameter and served as a benchmark metric during the model selection process in many instances [39]. Hence, the F1 score of the models were determined and found to lie between 0.635 and 0.692.

On the other hand, the accuracy of models after parameter tuning are LR (0.908), RF (0.889), SVM (0.912), NB (0.909), XGB (0.902), DT (0.770) and NN (0.872) respectively. It is to be noted that parameter tuning increased the accuracy of all the ML models drastically during the analysis. For instance, the accuracy of SVM was raised from 0.668 to 0.912 after parameter tuning process. Similar pattern of rise in the values were also observed in other performance metrices. In specific, F1 score of SVM model hiked from 0.694 to 0.913 after tuning process. In addition, ROC curve was also plotted to demonstrate the ability of the classifier system to differentiate between inhibitors and non-inhibitors (Fig. S2). The results show that SVM model prior and after parameter tuning achieved the highest AUC of 0.81 and 0.95 respectively than the other investigated models. The modest performance of SVM than other models might be due to its capability to handle high dimension data and implementation of kernel-based technique to overcome complex problems including over fitting.

Cross and external validation of models

5- and 10-fold CV were employed to evaluate the stratifying capability of the generated models after parameter tuning. The performance metrices of the ML classifiers with cross-validation are represented in Fig. 2 and Table S2. It is to be emphasised that no discernible variation in accuracy was observed for any of the generated ML models during the 5-fold cross-validation process. However, 10-fold CV improved the accuracy of DT and NB to more than 0.85. The improvement in accuracy may be attributable to the elimination of overfitting by averaging the errors during the validation process. Remarkably, SVM achieved the highest accuracy and F1 score of 0.98 and 0.90, respectively. Notably, the results correlate well with earlier findings of the study.

Fig. 2.

External and cross-validation of ML models generated using RET dataset

The fourth tier of model validation was accomplished with the external dataset containing 258 non-redundant structures and activity data retrieved from PubChem and ChEMBL database. The results are represented in Fig. 2 and Table S2. It is evident that the SVM had outperformed in stratifying the actives and inactives with an accuracy of 0.92 than other models in our study. On analysing the precision, recall and F1 score of the models in the current investigation, SVM achieved the highest scores of 0.893, 0.904 and 0.913, respectively, illustrating the capability of classifying the chemical compounds as actives and inactives with high precision. Thus, the findings of our study suggest that the generated SVM could be a great choice for designing a virtual pipeline for screening larger databases.

Machine learning-based virtual screening and molecular docking

The FDA approved subset of DrugBank database containing 2509 compounds were screened using the generated model to identify the potent RET inhibitor. The features were generated initially for all the 2509 compounds. The in-house SVM model was employed in the initial stages to screen out the actives from the data set. A total of 497 compounds were identified as active molecules by SVM model. The identified lead molecules were prepared and docked against the binding pocket of the RET protein using XP docking mode. The docking results highlights that about 381 compounds showed negative XP GScore revealing the effective binders against RET. Prominently, the reference ligand vandetanib exhibited XP GScore of − 10.102 kcal/mol. Subsequently, all the compounds were rescored using MM-GBSA and RF score in the current investigation for the precise prediction of binding energies.

Rescoring using MM-GBSA and machine learning strategy

Prime MM-GBSA module of Schrödinger suite was employed to estimate the binding free energy for the docked poses of the protein–ligand complexes. The summary of MM-GBSA analysis of each RET–ligand complex is tabulated in Table S3. The results revealed that the ΔGbind of the complex ranges from − 100.8 to − 8.71 kcal/mol. Note only two compounds DB09313 and DB00471 exhibited lower binding energy than vandetanib (− 96.66 kcal/mol). Among the different energy contributors, Van der Waals energy and coulomb energy were found to be the primary contributors towards the total binding affinity, ΔGbind. The contribution of covalent interaction is very minimal, thus depicts the thermostability characteristic and stabilized association of compounds with the RET protein to a greater extent. In contrast, the other molecules despite having better XP GScore than vandetanib, had exhibited higher ΔGbind, suggesting these molecules might be unfavourable to interact with RET protein. In addition, RF-score was also calculated for vandetanib and the two lead compounds to estimate the binding affinities against RET protein. Interestingly, both the compounds found to have greater RF score than vandetanib. Hence, these two lead molecules were considered for further evaluation. The overall results of the two lead compounds along with the reference is consolidated in Table 2.

Table 2.

MM-GBSA analysis of reference and lead compounds using Prime module of Schrödinger suite

| S. No | Compound ID | XP GScore (kcal/mol) | RF score | ΔGbind (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals energy (kcal/mol) | Coulomb’s energy (kcal/mol) | Covalent interaction (kcal/mol) | Lipophilicity (kcal/mol) | Solvation energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vandetanib | − 10.102 | 5.998 | − 96.66 | − 57.27 | − 16.23 | 1.71 | − 46.97 | 22.85 |

| 2 | DB09313 | − 7.757 | 6.186 | − 100.8 | − 55.27 | − 44.24 | 8.76 | − 43.22 | 34.52 |

| 3 | DB00471 | − 8.012 | 6.017 | − 99.68 | − 45.48 | − 42.29 | 2.89 | − 44.98 | 31.14 |

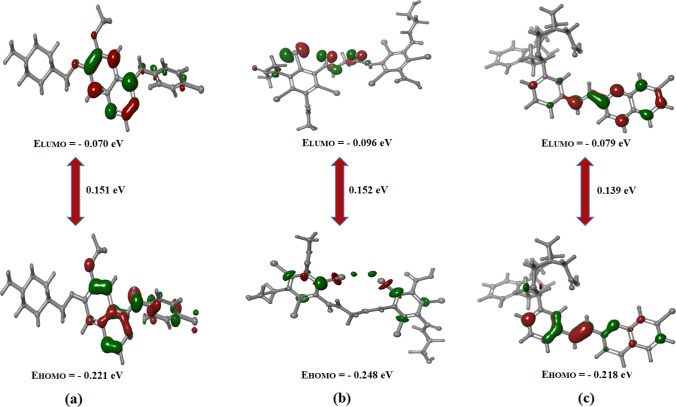

Density function theory calculations

Jaguar module of Schrödinger was used to calculate energy gap, ionization potential, hardness, softness and electron donating capability of the lead compounds. Initially, the molecules were optimized using LACV3P++** basis set and B3LYP-D3 theory. Subsequently, the energy gap between HOMO and LUMO were estimated to determine the chemical reactivity and electron donating capability of the compounds. The energy of the compounds in their HOMO–LUMO orbitals were calculated and the results are represented in Fig. 3. The distribution of positive and negative charge in the reactivity plot is represented in blue and red respectively. It is evident from figure that the compound DB00471 have minimal energy gap of 0.139 eV whereas DB09313 had equivalent energy gap (0.152 eV) to that of vandetanib (0.150 eV). Lower energy gap between the frontier orbitals indicates the favourable potential reaction and high chemical reactivity of the lead compounds against RET protein [40]. In addition, the higher energy in HOMO orbital than the LUMO shows the electron donating capability of the compounds, thus facility the hydrogen bond formation during interaction.

Fig. 3.

Energy difference analysis between the frontier molecular orbitals of reference a vandetanib and the lead compounds, b DB09313 and c DB00471

Besides, the stability and chemical reactivity of reference and the lead compounds were also assessed in terms of ionization potential, softness, hardness, electron negativity and electron affinity. It is evident from Table 3 that the scrutinized lead compounds exhibited higher ionization potential than electron affinity, which in turn depicts the electron donating nature of the molecules. Moreover, higher hardness and lower softness of the lead compounds than vandetanib reveals the better chemical reactivity characteristic of the molecules. In addition, the better chemical potential of our lead compounds than vandetanib depicts the electron donating capability of the compounds during interaction. The preceding results from our analysis reveals that the identified compounds DB09313 and DB00471 are highly stable and possess high chemical reactivity and electron donating capability.

Table 3.

Global descriptors of lead molecules calculated using the energy level LACV3P++**

| S. No | Compound ID | Ionization potential (IP) | Electron affinity (EA) | Hardness (η) | Softness (S) | Chemical potential (χ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vandetanib | 9.262 | 2.099 | 7.163 | 0.139 | 5.861 |

| 2 | DB09313 | 8.522 | 1.155 | 7.367 | 0.136 | 4.839 |

| 3 | DB00471 | 8.586 | 1.069 | 7.517 | 0.133 | 4.828 |

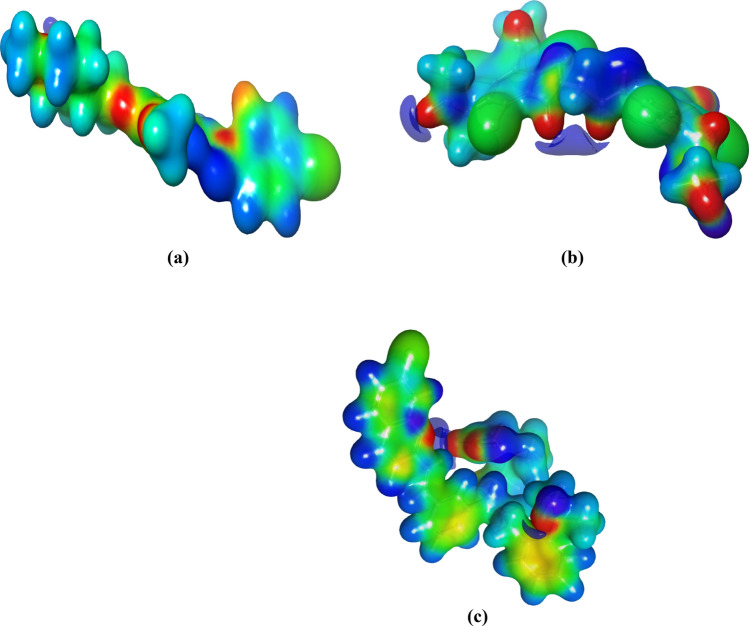

Electrostatic potential map

In an effort to comprehend the anti-cancer activity of compounds, electrostatic potential mapping (ESP) was plotted for the reference and the lead compounds (Fig. 4). In general, the ESP map represents the repulsive interaction of positive charged nuclei and negative charged electrons. Literature evidences report that higher negative potential of the compounds, greater will be the reactivity and vice versa [41]. The red colour in the figure indicates high electron density area i.e., negative potential and blue colour denotes positive potential of the compounds. On comparing the ESP map of the molecules, the compounds DB09313 and DB00471 exhibited increased negative potential on the surface than vandetanib. In specific, lower negative chemical potential of the lead molecules DB09313 (4.839) and DB00471 (4.828) shows the higher stability than the reference compound vandetanib (5.861). Thus, the results from our study propose that the selected compounds might exhibit higher anti-cancer activity than vandetanib.

Fig. 4.

Electrostatic potential map of reference a vandetanib and the lead compounds, b DB09313 and c DB00471

Pharmacokinetic and toxicity analysis

The pharmacokinetic and toxicity of the compounds were analysed using QikProp, ProTox II server and ADMET lab 2.0 tool to avoid elimination of the compounds in clinical trials. It is evident from Table 4 that the identified lead compounds have satisfactory ADMET properties. Notably, the human oral absorption of the lead compounds is similar to the reference compound vandetanib. The LD50 of the lead compounds DB09313 (20,000 mg/kg) and DB00471 (1350 mg/kg) were found to be greater than vandetanib (1000 mg/kg) indicating less harmfulness of the molecules in human body. Undeniably, the lead compound DB00471 did not exhibit any toxic effect including hepatotoxicity and immunogenicity. In general, the half-life a drug plays a significant role in research and development for determining the dosing regimen. Higher the half-life lower will be the dosage frequency. While, shorter half-life period results in inadequate safety and efficacy [42]. It is evident from the table that DB00471 had higher half-life period than the other compounds. Thus, DB00471 is found to possess greater capability to achieve safety and drug efficacy than DB09313 and vandetanib with minimal dosage frequency. Overall, the scrutinized compounds were less toxic and had satisfactory half-life than vandetanib.

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic, toxicity and inhibitory activity analysis of vandetanib and the lead compounds

| S. No | Compound name | CNS | HOA | Hepatotoxicity | Carcinogenicity | Immunogenicity | Mutagenicity | Cytotoxicity | LD50 (mg/kg) | Toxicity class | T1/2 (h) | IC50 µM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vandetanib | 1 | 1 | Active | Inactive | Active | Inactive | Inactive | 1000 | Class 4 | 1.06 | 11.924 |

| 2 | DB09313 | −2 | 1 | Inactive | Inactive | Active | Inactive | Active | 20,000 | Class 6 | 0.99 | 5.454 |

| 3 | DB00471 | −2 | 1 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 1350 | Class 4 | 9.92 | 1.436 |

Ligand–protein interaction analysis

The interaction pattern of the ligands to the RET protein binding pocket residues is visualized in Fig. S3. It is evident from Fig. S3a that vandetanib forms one hydrogen bond between positively charged ALA807 residue and the anilinoquinazoline group. On analyzing the interaction pattern of DB09313, four hydrogen bonds were found to be formed between the compound and the RET binding pocket. The hydrogen bonds formed between: (i) polar SER811 residue and O of tri-ionated benzoate scaffold, (ii) NH functional group and hydrophobic LEU730 residue, (iii) NH functional group and positively charged LYS808 residue and (iv) H-bond between OH group and polar ASN879 residue of RET protein. In addition, one halogen bond was found between hydrophobic TYR806 residue and iodine in the tri-ionated scaffold of DB09313. The literature evidences highlight that the formation of halogen bond between the ligand and the aromatic protein residue will significantly increase the residence time of the inhibitor in the human body [43]. Thus, the increased half-life period of DB09313 reported in Table 4 might be due to the halogen bond formation during the interaction. In the case of compound DB00471, three hydrogen bonds were observed in amino acid such as SER811, LEU730 and THR729. In addition, one halogen bond was observed between Cl group of chloroquinoline scaffold and negatively charged ASP892 residue. Likewise, two π–cation interaction was found to be formed between the aromatic moiety of DB00471 and the cation LYS728 residue. It is evident from literature that the formation of π–cation interaction between protein and ligand not only offers high specificity, selectivity and increased recognition by the protein target but also improves bioavailability of the compound [44]. Since two π–cation bonds were formed during the interaction of DB00471 against RET, we hope this compound might have increased bioavailability than DB09313 and vandetanib. Thus, the results of our study postulates that the screened lead compounds have significant interaction profile against RET protein than vandetanib.

Dynamic behaviour analysis of protein–ligand complexes

Stability analysis of RET–ligand complexes

The dynamic behaviour of protein–ligand complexes was analysed for 100 ns using gmx_rms utility of GROMACS. The extent of deviation of atoms within the RET–lead complex systems is outlined in Fig. 5. In the case of RET–vandetanib complex system, deviation of about ~ 0.4 nm RMSD was observed at 70 ns, demonstrating loss of stability in this region. Whereas, in the case of RET–DB00471 and RET–DB09313, no major deviations have been observed during the 100 ns simulation period which in turn depicts the greater stability of the complex systems throughout the whole dynamics simulation. Towards the end of 100 ns simulation, the average RMSD of RET–apoprotein, RET–vandetanib, RET–DB00471 and RET–DB09313 was observed to be 0.349, 0.341, 0.326 and 0.313 nm respectively. Hence, RMSD analysis reveals that the RET protein did not undergo any major confirmational changes and the lead molecules remained within the catalytic diad. A study by Guterres et al. revealed that a minimal mean RMSD lower than 0.4 nm is required for the ligand to reside within the binding site of the target protein [45]. Notably, the RMSD of the obtained lead molecules were observed to be lie within 0.3 nm and were apparently lower than RET–apoprotein and RET–vandetanib complex. From the results, we hypothesize that the obtained lead compounds might act as a potential inhibitor against the RET target with greater stability.

Fig. 5.

Mean RMSD of backbone atoms for RET–apoprotein and a RET–vandetanib complex, b RET–DB00471 and c RET–DB09313 complexes

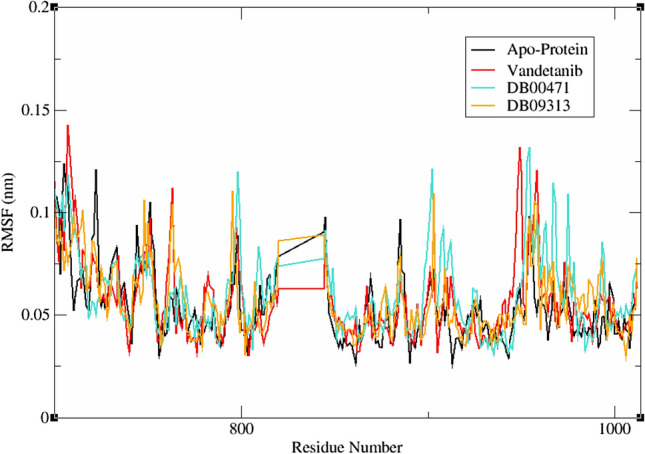

Fluctuation analysis of RET–ligand complexes

The fluctuation and mobility of protein residues within the complex systems were analysed using gmx rmsf tool (Fig. 6). In general, the high RMSF value denotes the loosely organized region whereas low RMSF value denotes well-structured ends [46]. In RET–vandetanib complex, GLY700, VAL706, ASP707, ALA708, PHE709, LYS710, ILE711, GLY949, ASN950 and GLU958 exhibited high flexibility. While LYS740, PHE776, VAL804 and PTR905 were found express subtle fluctuations. Similarly, in RET–DB00471 complex, around four residues namely THR754, GLY798, GLU902 and PRO953 displayed high flexibility whereas the residues TRP935, GLU943 and MET984 showed least fluctuation during the simulation. In case of RET–DB09313 complex, the residues GLY700, PRO715, GLY748, ASN763, SER795, ASP903, PRO957 and GLU958 disclosed higher fluctuation on binding of the ligand to the RET receptor. Conversely, LEU779, LEU802 and GLU1006 exhibited feeble fluctuation during the analysis. On examining the RMSF curve of RET–apoprotein in Fig. 6, several residual fluctuations were observed in the protein structure. These fluctuations were found to be minimized at the residues LEU702, LEU704, SER705, LYS722 and GLY751 upon the binding of DB00471 and DB09313. At the end of the analysis, the RET–DB00471 and RET–DB09313 complexes showed decreased average RMSF values of 0.0556 and 0.0423 nm than RET–vandetanib complex (0.0563 nm) and RET–apoprotein (0.0696 nm) which shows the ability of the lead molecules to bind against the important catalytic residues in protein with least fluctuation.

Fig. 6.

Time dependent root mean square fluctuation of reference and hit molecules

Stability analysis by hydrogen bond

Hydrogen bonds play a crucial role in maintaining the stability and compactness of the protein structure [40]. The number of H-bonds between protein and ligands were determined using gmx hbond and plotted against the duration of the simulation period (Fig. 7). The average number H-bonds formed during the 100 ns simulation, between RET protein and the ligands vandetanib, DB00471 and DB09313 are 0–2, 0–4 and 0–7 respectively. Although the RET-ligand complexes displayed similar binding pattern during docking, this study reveals that the number of H-bonds produced in aqueous solution is significantly higher for all the ligands except DB00471. This might possibly be attributed to the fact that docking is performed in the absence of solvent, whereas the simulation carried out in the presence of solvent can have a significant impact on ligand binding. From the hydrogen bond analysis, we predicted that the RET–DB00471 and RET–DB09313 complexes displayed more stability and compactness than RET–vandetanib complex due to increased number of H-bonds. This result correlates well with the RMSD and RMSF results.

Fig. 7.

Intermolecular H-bond interaction of RET–vandetanib, a RET–DB00471 and b RET–DB09313 complexes

Compactness analysis

The level of compactness and the level of RET protein folding in the presence of ligands were determined using inbuilt gyrate utility of GROMACS. In general, Rg indicates the weighted RMSD of all atoms calculated from its centre of mass [47]. Higher values of Rg indicates the protein unfolding within the system. Figure 8 demonstrates the Rg of RET–apoprotein and RET–ligand molecule complexes. The average Rg value for RET–apoprotein, RET–vandetanib, RET–DB00471 and RET–DB09313 were found to be 1.862, 1.953 nm, 1.858 nm and 1.929 nm respectively. RET–DB09313 and RET–DB00471 showed similar pattern of Rg till the end of 100 ns simulation. Moreover, DB00471 showed least Rg than other systems, illustrating more compactness in this complex. Altogether, this analysis reveals that RET–DB00471 was more stable and compact than RET–apoprotein and other RET–ligand complexes.

Fig. 8.

Radius of gyration extracted from the MD simulation studies of the complexes between RET–apoprotein and the ligands: a RET–vandetanib, b RET–DB00471 complexes, and c RET–DB09313 complexes

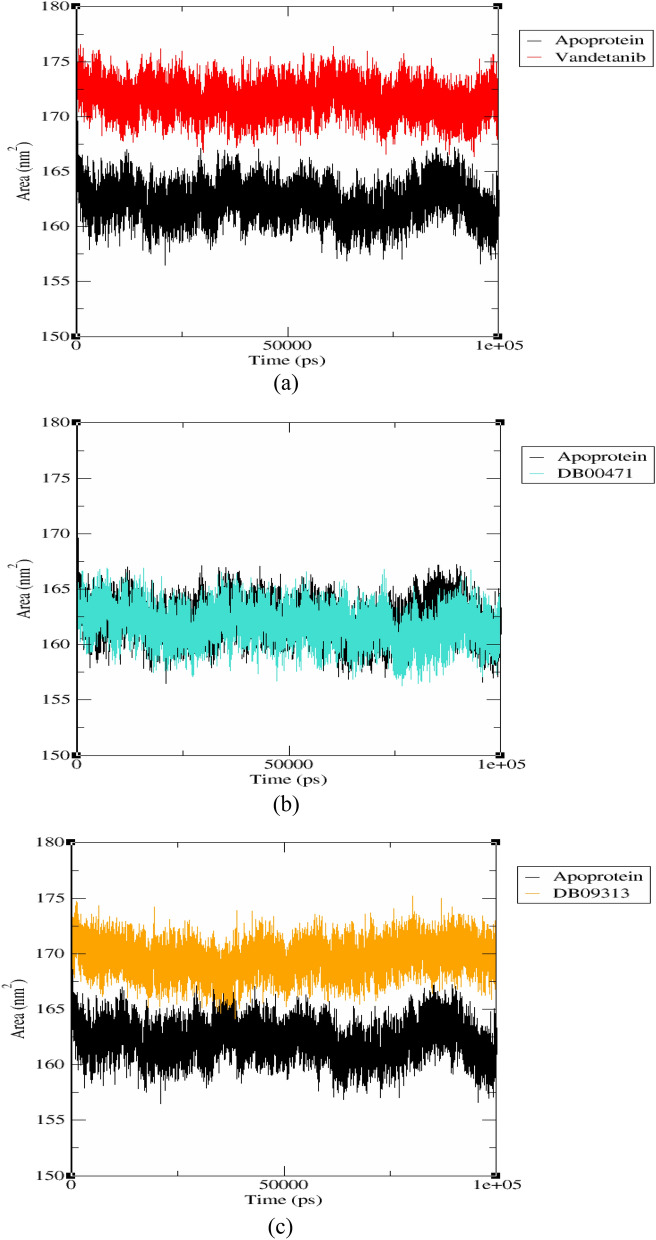

Solvent accessible surface area

The SASA of RET–apoprotein and RET–ligand complexes were analysed to determine the interacting surface area of RET protein with its solvent molecules [48]. This analysis was accomplished using gmx sasa utility of GROMACS. From Fig. 9, the average SASA values for RET–apoprotein, RET–vandetanib, RET–DB00471 and DB09313 were found to be 162.011 nm2, 169.747 nm2, 163.483 nm2 and 168.879 nm2, respectively. There were no major variations spotted in SASA values due to ligands binding. Moreover, all the RET–ligand complexes exhibited equivalent SASA values during the 100 ns simulation. Moreover, the RET–apoprotein, RET–vandetanib, RET–DB00471 and RET–DB09313 complexes displayed solvation free energy of 1084.566 nm2, 1136.356 nm2, 1094.419 nm2 and 1130.456 nm2 respectively. The equivalent solvation free energy of RET–ligand complexes to that of RET–apoprotein demonstrates the stability of the system upon ligand binding. Thus, the overall results highlight the compactness and stability of the protein–ligand complexes in the solvent area.

Fig. 9.

Solvent accessible surface area and free energy of solvation plot for RET–apoprotein and a RET–vandetanib, b RET–DB00471 and c RET–DB09313

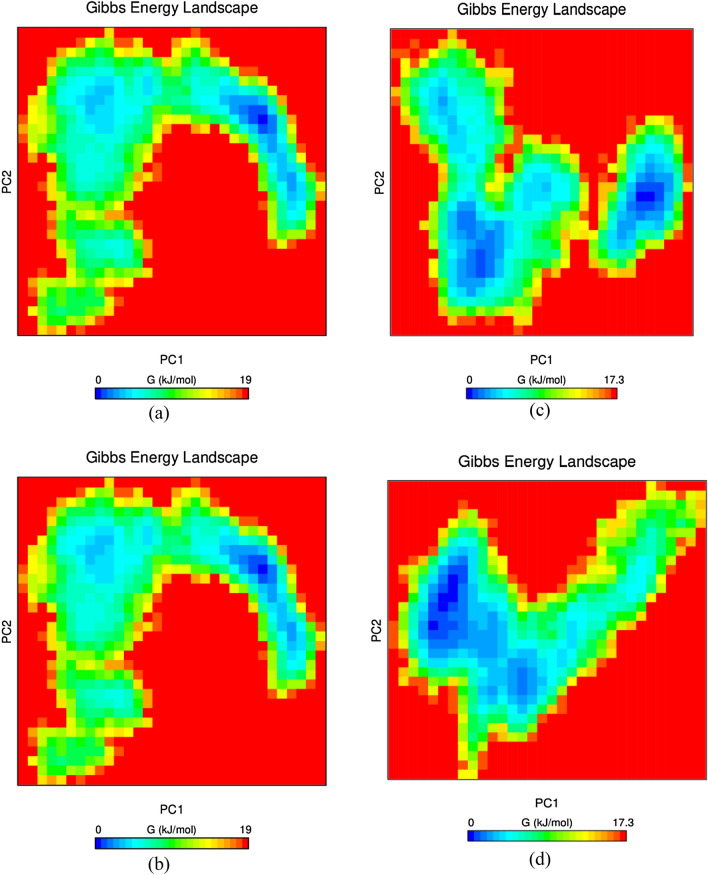

Essential dynamics and Gibbs free energy landscape

Essential dynamics describes the overall expansion of RET protein during the entire simulation period. Initially, gmx_covar and gmx_anaeig module of GROMACS was implemented to construct the covariance matrix comprising eigen values. The traces of covariance matrix for RET–apoprotein, RET–vandetanib, RET–DB00471 and RET–DB09313 were found to be 7.121 nm2, 10.535 nm2, 8.018 nm2 and 7.54 nm2 respectively. The eigen values for RET–apoprotein are comparatively lower than the other complexes which clearly demonstrates the rise of random fluctuation of protein upon ligand binding. Further, the Gibbs FEL between first two principal components were plotted in Fig. 10. The yellow colour in the corresponding contour map indicates the unfavourable conformation whereas dark blue colour denotes the energy minima favoured complex conformation. The energy landscape reveals a collection of distinct minima that are related to the metastable conformational states and are separated from one another by a negligible energy barrier. The more stable conformation states were observed in the binding sites of RET–DB00471, DB09313 and RET–DB09313, with local minima dispersed throughout three to four energy landscape areas. It is evident from Fig. 10 that RET–DB00471 and DB09313 possessed minimum of one deep and narrow energy basin whereas RET–apoprotein and RET–vandetanib contained shallow energy basins. Thus, the FEL analysis it is clear that the RET–lead molecule complexes were found to be thermodynamically stable than RET–apoprotein and RET–vandetanib complex.

Fig. 10.

Gibbs free energy landscape of a RET–apoprotein, b RET–vandetanib complex, c RET–DB00471 complex and d RET–DB09313 complex system

Scaffold analysis

The parent scaffold of all compounds is highlighted in Fig. S4. Vandetanib is one of the widely used MKI with naphthyridine scaffold in its structure. This scaffold is widely found in therapeutics with wide spectrum of biological roles including anticancer, antifungal, antimalarial and antibacterial activity. The compounds containing naphthyridine scaffold serve as a promising antitumor agent by modulating DNA conformation ultimately resulting in inhibition of DNA transcription or duplication [49]. On the other hand, DB00471 is a chloroquinoline derivate widely involved in antiproliferation and anticancer activities. These derivates exert antitumour activity via apoptotic responses and by regulating cell cycle arrest [50]. Similarly, DB09313 possess tri-ionated benzoic acid in its structure which widely serves as contrasting agents during cancer diagnosis and treatment. These derivatives act on various cellular pathways which were found to be highly related to induction of apoptosis, modulation of cell proliferation and survival and antitumour activity [51]. Although the identified two lead compounds differ in terms of their parent scaffolds than vandetanib, literature evidences highlight the role of these scaffolds in tumour suppression.

Inhibitory activity prediction of ligands

Despite significant investments in drug development and repurposing, 97% of anticancer drugs fail in clinical trials due to off-target cytotoxicity and low target efficacy [52]. Hence, the effect of candidate drug molecules on specific biomolecular profiles were determined using PaccMann server. In the current investigation, the inhibitory activity of vandetanib and the lead molecules were determined over 2022 different cancer cell lines. Particularly, the activity of compounds was analysed against RET protein expressing LC-2/ad cell lines. In general, lower IC50 value indicates inhibition of 50% of cells with minimal concentration of drugs. From Table 4, it is evident that DB00471 have the least IC50 than vandetanib and DB09313. Thus, the results clearly shows that DB00471 have the potential to inhibit RET positive cancer cell in minimal concentration and with lower systemic toxicity.

On deciphering the existing application of the drugs, DB00471 denotes the drug montelukast, a selective leukotriene antagonist. It is widely used as an orally dosed drug for asthma, exercise-induced bronco-construction and seasonal allergic rhinitis [53]. Interestingly, a recent study revealed the apoptosis mediated cell death of lung cancer cells in A549 and CL1-5 cell lines [54]. Similarly, montelukast inhibited the growth of myeloid leukaemia cells with IC50 of 2 µM through apoptosis [55]. In the light of these evidences, we propose from our study that montelukast (DB00471) could also be repurposed against RET driven NSCLC patients.

The main barrier to the use of RET inhibitors, which results in decreased therapeutic effectiveness in NSCLC patients, is acquired drug resistance. Although the identified hit compound can demonstrate potent activity against wild type RET receptor, mutational analysis and experimental validation of the compound activity against cell lines is certainly needed to validate this finding. Moreover, future research on the toxicity of this substance using the in vitro genotoxicity assay or the in vivo micronucleus assay is also intriguing. The ML strategy in our study opens a new avenue for the biologist to identify highly effective compound within a short period of time and low cost. Finally, the outcomes of our work will help hit-to-lead optimization in the near future to find new molecules with potential value.

Conclusion

In the current investigation, the in-house ML model built using 2854 compounds was employed to assess the inhibitory potency of FDA approved drug molecules against RET protein. The robustness of the models was analysed using three tiers of evaluation process including 5-fold cross validation, 10-fold cross validation alongside external dataset containing 287 non-redundant compounds. The in-house SVM model with highest accuracy of 0.91 retrieved 497 actives from DrugBank repository against RET receptor. The obtained compounds were further subjected to diverse computational techniques such as molecular docking, RF score, MMGBSA and DFT provides two hit compounds, DB09313 (Ioxaglic acid) and DB00471 (Montelukast). Finally, the stability analysis using molecular dynamic simulation of these two active molecules resulted in identification of montelukast as a prominent inhibitor against RET protein. It is to be noted that montelukast demonstrated cytotoxic activity against various lung cancer cell lines including A549 and CL1-5 together with adequate pharmacokinetic and ADMET profiles. Based on these collective evidences and findings, we hypothesize that montelukast could be utilised in treating RET positive NSCLC patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank management of Vellore Institute of Technology and Indian Council of Medical Research for providing the necessary facility to carry out this research work.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by PR. RK and SV conceived this study and responsible for the overall design, interpretation, manuscript preparation, and communication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang M, Naganna N, Sintim HO. Identification of nicotinamide aminonaphthyridine compounds as potent RET kinase inhibitors and antitumor activities against RET rearranged lung adenocarcinoma. Bioorg Chem. 2019;90:103052. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendoza L. Clinical development of RET inhibitors in RET-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer: update. Oncol Rev. 2018;12(2):352. doi: 10.4081/oncol.2018.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara R, Auger N, Auclin E, Besse B. Clinical and translational implications of RET rearrangements in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subbiah V, Gainor JF, Rahal R, Brubaker JD, Kim JL, Maynard M, Hu W, Cao Q, Sheets MP, Wilson D, Wilson KJ, DiPietro L, Fleming P, Palmer M, Hu MI, Wirth L, Brose MS, Ou SI, Taylor M, Garralda E, Miller S, Wolf B, Lengauer C, Guzi T, Evans EK. Precision targeted therapy with BLU-667 for RET-driven cancers. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(7):836–849. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramesh P, Veerappapillai S. Designing novel compounds for the treatment and management of RET-positive non-small cell lung cancer-fragment based drug design strategy. Molecules. 2022;27(5):1590. doi: 10.3390/molecules27051590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subbiah V, Yang D, Velcheti V, Drilon A, Meric-Bernstam F. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting RET-dependent cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(11):1209–1221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parate S, Kumar V, Hong JC, Lee KW. Putative dual inhibitors of mTOR and RET kinase from natural products: pharmacophore-based hierarchical virtual screening. J Mol Liq. 2022;350:118562. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramesh P, Shin WH, Veerappapillai S. Discovery of a potent candidate for RET-specific non-small-cell lung cancer—a combined in silico and in vitro strategy. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(11):1775. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharya S, Asati V, Ali A, Ali A, Gupta GD. In silico studies for the development of novel RET inhibitors for cancer treatment. J Mol Struct. 2022;1251:132040. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhamodharan G, Mohan CG. Machine learning models for predicting the activity of AChE and BACE1 dual inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Divers. 2022;26(3):1501–1517. doi: 10.1007/s11030-021-10282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadioglu O, Saeed M, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Identification of novel compounds against three targets of SARS CoV-2 coronavirus by combined virtual screening and supervised machine learning. Comput Biol Med. 2021;133:104359. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao A, Kouznetsova VL, Tsigelny IF. Machine-learning-based virtual screening to repurpose drugs for treatment of Candida albicans infection. Mycoses. 2022;65(8):794–805. doi: 10.1111/myc.13475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwaloye O, Elekofehinti OO, Kikiowo B, Oluwarotimi EA, Fadipe TM. Machine learning-based virtual screening strategy reveals some natural compounds as potential PAK4 inhibitors in triple negative breast cancer. Curr Proteomics. 2021;18(5):753–769. doi: 10.2174/1570164618999201223092209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raju B, Verma H, Narendra G, Sapra B, Silakari O. Multiple machine learning, molecular docking, and ADMET screening approach for identification of selective inhibitors of CYP1B1. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;26:1–16. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1905552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vetrivel A, Ramasamy J, Natchimuthu S, Senthil K, Ramasamy M, Murugesan R. Combined machine learning and pharmacophore based virtual screening approaches to screen for antibiofilm inhibitors targeting LasR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2064331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermansyah O, Bustamam A, Yanuar A. Virtual screening of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors using quantitative structure–activity relationship-based artificial intelligence and molecular docking of hit compounds. Comput Biol Chem. 2021;95:107597. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2021.107597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricci-Lopez J, Aguila SA, Gilson MK, Brizuela CA. Improving structure-based virtual screening with ensemble docking and machine learning. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61(11):5362–5376. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendolia I, Contino S, Perricone U, Ardizzone E, Pirrone R. Convolutional architectures for virtual screening. BMC Bioinform. 2020;21(Suppl 8):310. doi: 10.1186/s12859-020-03645-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilson MK, Liu T, Baitaluk M, Nicola G, Hwang L, Chong J. BindingDB in 2015: a public database for medicinal chemistry, computational chemistry and systems pharmacology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44(D1):D1045–D1053. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia CC, Chen W, Feng ZL, Liu ZP. Recent developments of RET protein kinase inhibitors with diverse scaffolds as hinge binders. Future Med Chem. 2021;13(1):45–62. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2020-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakaoku T, Kohno T, Araki M, Niho S, Chauhan R, Knowles PP, Tsuchihara K, Matsumoto S, Shimada Y, Mimaki S, Ishii G. A secondary RET mutation in the activation loop conferring resistance to vandetanib. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02994-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong J, Yao ZJ, Zhu MF, Wang NN, Lu B, Chen AF, Lu AP, Miao H, Zeng WB, Cao DS. ChemSAR: an online pipelining platform for molecular SAR modeling. J Cheminform. 2017;9(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13321-017-0215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap CW. PaDEL-descriptor: an open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J Comput Chem. 2011;32(7):1466–1474. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramesh P, Veerappapillai S. Prediction of micronucleus assay outcome using in vivo activity data and molecular structure features. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;193(12):4018–4034. doi: 10.1007/s12010-021-03720-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misra P, Yadav AS. Improving the classification accuracy using recursive feature elimination with cross-validation. Int J Emerg Technol. 2020;11(3):659–665. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elavarasan D, Vincent DR, Sharma V, Zomaya AY, Srinivasan K. Forecasting yield by integrating agrarian factors and machine learning models: a survey. Comput Electron Agric. 2018;155:257–282. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2018.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dwivedi AK. Artificial neural network model for effective cancer classification using microarray gene expression data. Neural Comput Appl. 2018;29(12):1545–1554. doi: 10.1007/s00521-016-2701-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Marcu A, Grant JR, Sajed T, Johnson D, Li C, Sayeeda Z, Assempour N, Iynkkaran I, Liu Y, Maciejewski A, Gale N, Wilson A, Chin L, Cummings R, Le D, Pon A, Knox C, Wilson M. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knowles PP, Murray-Rust J, Kjær S, Scott RP, Hanrahan S, Santoro M, Ibáñez CF, McDonald NQ. Structure and chemical inhibition of the RET tyrosine kinase domain. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(44):33577–33587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Xie W, Yang Y, Hua Y, Xing G, Liang L, Deng C, Wang Y, Fan Y, Liu H, Lu T, Chen Y, Zhang Y. Discovery of dual FGFR4 and EGFR inhibitors by machine learning and biological evaluation. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60(10):4640–4652. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peele KA, Potla Durthi C, Srihansa T, Krupanidhi S, Ayyagari VS, Babu DJ, Indira M, Reddy AR, Venkateswarulu TC. Molecular docking and dynamic simulations for antiviral compounds against SARS-CoV-2: a computational study. Inform Med Unlocked. 2020;19:100345. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2020.100345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mali SN, Chaudhari HK. Computational studies on imidazo [1, 2-a] pyridine-3-carboxamide analogues as antimycobacterial agents: common pharmacophore generation, atom-based 3D-QSAR, molecular dynamics simulation, QikProp, molecular docking and prime MMGBSA approaches. Open Pharm Sci J. 2018 doi: 10.2174/1874844901805010012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee P, Eckert AO, Schrey AK, Preissner R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiong G, Wu Z, Yi J, Fu L, Yang Z, Hsieh C, Yin M, Zeng X, Wu C, Lu A, Chen X, Hou T, Cao D. ADMET lab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W5–W14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wójcikowski M, Ballester PJ, Siedlecki P. Performance of machine-learning scoring functions in structure-based virtual screening. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46710. doi: 10.1038/srep46710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali S, Khan FI, Mohammad T, Lan D, Hassan MI, Wang Y. Identification and evaluation of inhibitors of lipase from Malassezia restricta using virtual high-throughput screening and molecular dynamics studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(4):884. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cadow J, Born J, Manica M, Oskooei A, Rodríguez MM. PaccMann: a web service for interpretable anticancer compound sensitivity prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W502–W508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stark GF, Hart GR, Nartowt BJ, Deng J. Predicting breast cancer risk using personal health data and machine learning models. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alabi RO, Elmusrati M, Sawazaki-Calone I, Kowalski LP, Haglund C, Coletta RD, Mäkitie AA, Salo T, Almangush A, Leivo I. Comparison of supervised machine learning classification techniques in prediction of locoregional recurrences in early oral tongue cancer. Int J Med Inform. 2020;136:104068. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.104068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madhavaram M, Nampally V, Gangadhari S, Palnati MK, Tigulla P. High-throughput virtual screening, ADME analysis, and estimation of MM/GBSA binding-free energies of azoles as potential inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2019;39(4):312–320. doi: 10.1080/10799893.2019.1660895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Henawy AA, Khowdiary MM, Badawi AB, Soliman HM. In vivo anti-leukemia, quantum chemical calculations and ADMET investigations of some quaternary and isothiouronium surfactants. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2013;6(5):634–649. doi: 10.3390/ph6050634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith DA, Beaumont K, Maurer TS, Di L. Relevance of half-life in drug design. J Med Chem. 2018;61(10):4273–4282. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heroven C, Georgi V, Ganotra GK, Brennan P, Wolfreys F, Wade RC, Fernández-Montalván AE, Chaikuad A, Knapp S. Halogen-aromatic π interactions modulate inhibitor residence times. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57(24):7220–7224. doi: 10.1002/anie.201801666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang Z, Li QX. π–Cation interactions in molecular recognition: perspectives on pharmaceuticals and pesticides. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(13):3315–3323. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guterres H, Im W. Improving protein–ligand docking results with high-throughput molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60(4):2189–2198. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amala M, Rajamanikandan S, Prabhu D, Surekha K, Jeyakanthan J. Identification of anti-filarial leads against aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase of Wolbachia endosymbiont of Brugia malayi: combined molecular docking and molecular dynamics approaches. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;37(2):394–410. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1427633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shukla R, Shukla H, Sonkar A, Pandey T, Tripathi T. Structure-based screening and molecular dynamics simulations offer novel natural compounds as potential inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyase. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2018;36(8):2045–2057. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2017.1341337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar R, Bansal A, Shukla R, Raj Singh T, Wasudeo Ramteke P, Singh S, Gautam B. In silico screening of deleterious single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and molecular dynamics simulation of disease associated mutations in gene responsible for oculocutaneous albinism type 6 (OCA 6) disorder. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;37(13):3513–3523. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.15206493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-romaizan AN, Jaber TS, Ahmed NS. Novel 1, 8-naphthyridine derivatives: design, synthesis and in vitro screening of their cytotoxic activity against MCF7 cell line. Open Chem. 2019;17(1):943–954. doi: 10.1515/chem-2019-0097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuang WB, Huang RZ, Fang YL, Liang GB, Yang CH, Ma XL, Zhang Y. Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel 2-chloro-3-(1H-benzo [d] imidazol-2-yl) quinoline derivatives as antitumor agents: in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity, cell cycle arrest and apoptotic response. RSC Adv. 2018;8(43):24376–24385. doi: 10.1039/C8RA04640A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Abreu JS, Fernandes J. Iodinated contrast agents and their potential for antitumor chemotherapy. Curr Top Biochem Res. 2021;22:119–37.

- 52.Wong CH, Siah KW, Lo AW. Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics. 2019;20(2):273–286. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxx069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wermuth HR, Badri T, Takov V. Montelukast. StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459301/. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

- 54.Tsai MJ, Chang WA, Tsai PH, Wu CY, Ho YW, Yen MC, Lin YS, Kuo PL, Hsu YL. Montelukast induces apoptosis-inducing factor-mediated cell death of lung cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1353. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zovko A, Yektaei-Karin E, Salamon D, Nilsson A, Wallvik J, Stenke L. Montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist, inhibits the growth of chronic myeloid leukemia cells through apoptosis. Oncol Rep. 2018;40(2):902–908. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.