ABSTRACT

Members of the Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC) are important opportunistic nosocomial pathogens that are associated with a great variety of infections. Due to limited data on the genome-based classification of species and investigation of resistance mechanisms, in this work, we collected 172 clinical ECC isolates between 2019 and 2020 from three hospitals in Zhejiang, China and performed a retrospective whole-genome sequencing to analyze their population structure and drug resistance mechanisms. Of the 172 ECC isolates, 160 belonged to 9 classified species, and 12 belonged to unclassified species based on ANI analysis. Most isolates belonged to E. hormaechei (45.14%) followed by E. kobei (13.71%), which contained 126 STs, including 62 novel STs, as determined by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis. Pan-genome analysis of the two ECC species showed that they have an “open” tendency, which indicated that their Pan-genome increased considerably with the addition of new genomes. A total of 80 resistance genes associated with 11 antimicrobial agent categories were identified in the genomes of all the isolates. The most prevailing resistance genes (12/29, 41.38%) were related to β-lactams followed by aminoglycosides. A total of 247 β-lactamase genes were identified, of which the blaACT genes were the most dominant (145/247, 58.70%), followed by the blaTEM genes (21/247, 8.50%). The inherent ACT type β-lactamase genes differed among different species. blaACT-2 and blaACT-3 were only present in E. asburiae, while blaACT-9, blaACT-12, and blaACT-6 exclusively appeared in E. kobei, E. ludwigii, and E. mori. Among the six carbapenemase-encoding genes (blaNDM-1, blaNDM-5, blaIMP-1, blaIMP-4, blaIMP-26, and blaKPC-2) identified, two (blaNDM-1 and blaIMP-1) were identified in an ST78 E. hormaechei isolate. Comparative genomic analysis of the carbapenemase gene-related sequences was performed, and the corresponding genetic structure of these resistance genes was analyzed. Genome-wide molecular characterization of the ECC population and resistance mechanism would offer valuable insights into the effective management of ECC infection in clinical settings.

IMPORTANCE The presence and emergence of multiple species/subspecies of ECC have led to diversity and complications at the taxonomic level, which impedes our further understanding of the epidemiology and clinical significance of species/subspecies of ECC. Accurate identification of ECC species is extremely important. Also, it is of great importance to study the carbapenem-resistant genes in ECC and to further understand the mechanism of horizontal transfer of the resistance genes by analyzing the surrounding environment around the genes. The occurrence of ECC carrying two MBL genes also indicates that the selection pressure of bacteria is further increased, suggesting that we need to pay special attention to the emergence of such bacteria in the clinic.

KEYWORDS: Enterobacter cloacae complex, whole-genome sequencing-based species classification, MLST, antimicrobial resistance mechanism, Pan-genome

INTRODUCTION

The Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC) is one of the most common nosocomial pathogens causing healthcare-associated infections involving pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and septicemia (1). Previous studies have reported that the E. cloacae complex mainly comprises six species, including E. cloacae, Enterobacter asburiae, Enterobacter hormaechei, Enterobacter kobei, Enterobacter ludwigii, and Enterobacter nimipressuralis (2). Among them, E. hormaechei and E. cloacae are most frequently isolated from human clinical specimens (3). Based on the rapid development of next-generation sequencing, the most widely used method of species identification, hsp60 typing, could be replaced by comparison of the sequenced Enterobacter genomes through whole-genome sequencing (WGS), which provides higher resolution to distinguish the E. cloacae complex at the taxonomic level. The ECC has been further classified into clades (A to V), including the Hoffmann cluster (I to XII) (4, 5).

Most isolates of the ECC produce the chromosomally encoded AmpC β-lactamase and intrinsically exhibit resistance to several antimicrobial agents, such as ampicillin, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and first- and second-generation cephalosporins, whereas they are generally susceptible to fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, piperacillin-tazobactam, and carbapenems (2). Due to the selective pressure of antimicrobials in the clinic, an increasing number of ECC isolates carrying different acquired resistance genes have been detected. The ECC has become the third major drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae species associated with nosocomial infections following Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae due to the prevalence of Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases in the constituent species (6). The most clinically prevalent ESBLs are TEM, SHV, and CTX-M enzymes (7), and the major types of carbapenemases are KPC, NDM, and IMP/VIM (8). In China, the first reported carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae was KPC-2, identified in Shanghai in 2007 (9), and more types of carbapenemases (IMP, VIM, and NDM) have been identified in different geographical regions (10–12). The acquisition of these genes is most often associated with mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids and transposons, that can be easily transferred between different species.

In this work, we performed a retrospective whole-genome sequencing to analyze the population structure and the distribution of resistance genes, especially focusing on resistance genes more concerned in the clinic (ESBLs and carbapenemases), among 172 clinical E. cloacae complex isolates collected between 2019 and 2020 from Zhejiang, China. We observed and identified a novel isolate that harbored two metallobeta-lactamases (MBLs).

RESULTS

Characteristics of clinical ECC isolates.

A total of 172 ECC strains were isolated from different sources: wound secretion (n = 55), sputum (n = 46), urine (n = 21), throat swab (n = 13), blood (n = 11), pus (n = 10), bile (n = 5), ascites (n = 3), bronchoalveolar lavage (n = 2), tissue (n = 2), drainage (n = 2), catheter (n = 1), and semen (n = 1). The average nucleotide identity (ANI) results of 172 isolates revealed that the predominant species was E. hormaechei (n = 79) followed by E. kobei (n = 24), E. roggenkampii (n = 15), E. asburiae (n = 14), E. bugandensis (n = 13), E. cloacae (n = 10), E. ludwigii (n = 3), and E. mori (n = 3). Twelve isolates with ANI values below the threshold (95%) for the classified species/subspecies were grouped into 4 clades (L, O, P, and T) (Table 1; Fig. 1). These 172 ECC isolates exhibited high susceptibility to amikacin (98.8%), gentamicin (93.6%), meropenem (90.1%), ciprofloxacin (78.5%), cefepime (77.3%), tigecycline (76.7%), ceftazidime (71.5%), chloramphenicol (68.6%), fosfomycin (59.9%), and tetracycline (54.7%) and low susceptibility to colistin (28.0%), ampicillin (0.6%), and cefoxitin (0%) (Table 2). Ten isolates (5.8%, 10/172) exhibited an ESBL-positive phenotype, most of which belonged to E. hormaechei (n = 6), followed by E. kobei (n = 2). Among the 14 isolates with carbapenem resistance phenotypes, E. hormaechei was the predominant species (n = 9) followed by E. kobei (n = 3).

TABLE 1.

ECC isolates used in this study

| Strain | Species | Clade | hsp60 typing | ST | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | E. asburiae | J | I | 1682-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 2 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 110 | Hangzhou |

| 4 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 511 | Hangzhou |

| 5 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 112 | Hangzhou |

| 6 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 461 | Hangzhou |

| 7 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1707-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 9 | E. ludwigii | I | V | 1708-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 10 | E. kobei | Q | II | 56 | Hangzhou |

| 11 | E. kobei | Q | II | 56 | Hangzhou |

| 12 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 133 | Hangzhou |

| 13 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1683-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 14 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 110 | Hangzhou |

| 15 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 110 | Hangzhou |

| 16 | E. kobei | Q | II | 125 | Hangzhou |

| 19 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1681-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 20 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 501 | Hangzhou |

| 21 | E. kobei | Q | II | 365 | Hangzhou |

| 22 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1685-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 23 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 550 | Hangzhou |

| 24 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 536 | Hangzhou |

| 25 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 175 | Hangzhou |

| 27 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 45 | Hangzhou |

| 29 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 776 | Hangzhou |

| 31 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 46 | Hangzhou |

| 32 | E. asburiae | J | I | 1692-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 33 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 78 | Hangzhou |

| 34 | E. kobei | Q | II | 56 | Hangzhou |

| 35 | E. kobei | Q | II | 423 | Hangzhou |

| 36 | E. ludwigii | I | V | 1693-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 37 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1694-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 38 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1695-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 39 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 78 | Hangzhou |

| 41 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 78 | Hangzhou |

| 42 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1696-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 43 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 50 | Hangzhou |

| 44 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1697-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 45 | E. kobei | Q | II | 125 | Hangzhou |

| 46 | E. asburiae | J | I | 252 | Hangzhou |

| 49 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1698-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 50 | E. mori | F | 1699-NEW | Hangzhou | |

| 51 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1698-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 54 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 78 | Hangzhou |

| 55 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 114 | Hangzhou |

| 58 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1700-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 59 | E. hormaechei subsp. hormaechei | E | VII | 269 | Hangzhou |

| 60 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1698-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 61 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1711-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 62 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1701-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 63 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 724 | Hangzhou |

| 64 | E. cloacae complex | T | 1702-NEW | Hangzhou | |

| 65 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 718 | Hangzhou |

| 66 | E. ludwigii | I | V | 1703-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 67 | E. cloacae complex | T | 1702-NEW | Hangzhou | |

| 68 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 78 | Hangzhou |

| 69 | E. cloacae complex | T | 1704-NEW | Hangzhou | |

| 70 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 718 | Hangzhou |

| 71 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 1705-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 72 | E. cloacae complex | L | 414 | Hangzhou | |

| 73 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1601-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 74 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 78 | Hangzhou |

| 75 | E. mori | F | 1706-NEW | Hangzhou | |

| 77 | E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii | D | III | 78 | Hangzhou |

| 79 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 501 | Hangzhou |

| 81 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1698-NEW | Hangzhou |

| 102 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 554 | Wenzhou |

| 103 | E. asburiae | J | I | 25 | Wenzhou |

| 104 | E. cloacae complex | O | 1647-NEW | Wenzhou | |

| 105 | E. asburiae | J | I | 1648-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 106 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1651-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 108 | E. cloacae complex | L | 414 | Wenzhou | |

| 109 | E. kobei | Q | II | 280 | Wenzhou |

| 110 | E. cloacae complex | L | 414 | Wenzhou | |

| 111 | E. asburiae | J | I | 1649-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 112 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1651-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 114 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 1650-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 115 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1651-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 116 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 43 | Wenzhou |

| 117 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1652-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 118 | E. cloacae subsp. dissolvens | H | XII | 1653-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 120 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 120 | Wenzhou |

| 121 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 136 | Wenzhou |

| 122 | E. cloacae complex | L | 414 | Wenzhou | |

| 123 | E. mori | F | 1655-NEW | Wenzhou | |

| 125 | E. asburiae | J | I | 1656-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 126 | E. kobei | Q | II | 563 | Wenzhou |

| 127 | E. kobei | Q | II | 563 | Wenzhou |

| 128 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 331 | Wenzhou |

| 130 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1657-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 131 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1658-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 132 | E. asburiae | J | I | 317 | Wenzhou |

| 133 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1661-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 134 | E. cloacae subsp. dissolvens | H | XII | 1659-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 135 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1032 | Wenzhou |

| 136 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 412 | Wenzhou |

| 137 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1660-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 138 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1660-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 140 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1660-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 141 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 412 | Wenzhou |

| 142 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 406 | Wenzhou |

| 143 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1661-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 144 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1662-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 145 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1497-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 146 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 127 | Wenzhou |

| 147 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 182 | Wenzhou |

| 148 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1663-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 149 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 65 | Wenzhou |

| 150 | E. kobei | Q | II | 32 | Wenzhou |

| 151 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 116 | Wenzhou |

| 152 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1664-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 153 | E. kobei | Q | II | 56 | Wenzhou |

| 154 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 1665-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 155 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 557 | Wenzhou |

| 156 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1085 | Wenzhou |

| 157 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1666-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 158 | E. cloacae complex | O | 1667-NEW | Wenzhou | |

| 159 | E. hormaechei subsp. oharae | C | VI | 1668-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 160 | E. asburiae | J | I | 53 | Wenzhou |

| 161 | E. cloacae complex | L | 1669-NEW | Wenzhou | |

| 162 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 407 | Wenzhou |

| 163 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 264 | Wenzhou |

| 164 | E. asburiae | J | I | 1670-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 165 | E. cloacae complex | P | 669 | Wenzhou | |

| 166 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 418 | Wenzhou |

| 167 | E. asburiae | J | I | 610 | Wenzhou |

| 168 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1671-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 169 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 501 | Wenzhou |

| 170 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 1672-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 171 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 554 | Wenzhou |

| 172 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 171 | Wenzhou |

| 174 | E. asburiae | J | I | 1673-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 176 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 272 | Wenzhou |

| 177 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 407 | Wenzhou |

| 179 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 1674-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 180 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1675-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 181 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 171 | Wenzhou |

| 182 | E. kobei | Q | II | 280 | Wenzhou |

| 183 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 171 | Wenzhou |

| 185 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1676-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 186 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 524 | Wenzhou |

| 187 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1116 | Wenzhou |

| 188 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 1677-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 189 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 171 | Wenzhou |

| 190 | E. kobei | Q | II | 125 | Wenzhou |

| 191 | E. cloacae subsp. cloacae | G | XI | 1678-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 193 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 980 | Wenzhou |

| 194 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 171 | Wenzhou |

| 195 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 346 | Wenzhou |

| 196 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1679-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 197 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1680-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 198 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 171 | Wenzhou |

| 199 | E. kobei | Q | II | 691 | Wenzhou |

| 200 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 758 | Wenzhou |

| 201 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 45 | Wenzhou |

| 202 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1029 | Wenzhou |

| 203 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1029 | Wenzhou |

| 204 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1683-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 205 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 127 | Wenzhou |

| 206 | E. roggenkampii | M | IV | 501 | Wenzhou |

| 207 | E. asburiae | J | I | 27 | Wenzhou |

| 208 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 92 | Wenzhou |

| 209 | E. cloacae complex | L | 414 | Wenzhou | |

| 210 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 182 | Wenzhou |

| 211 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1684-NEW | Wenzhou |

| 212 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1243 | Wenzhou |

| 302 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1687-NEW | Huzhou |

| 303 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 599 | Huzhou |

| 305 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 267 | Huzhou |

| 306 | E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis | A | VI | 1689-NEW | Huzhou |

| 307 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 1690-NEW | Huzhou |

| 308 | E. kobei | Q | II | 1691-NEW | Huzhou |

| 309 | E. hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii | B | VIII | 93 | Huzhou |

| 310 | E. bugandensis | R | IX | 718 | Huzhou |

FIG 1.

SNP phylogenetic tree of the genomes of 172 E. cloacae complex isolates. The species/subspecies, clades, and Hoffmann clusters are drawn in concentric circles.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility profiles and MICs for 172 ECC strains

| Antibiotics | % Resistant | % Intermediate | % Susceptible | MIC50 (mg/L) | MIC90 (mg/L) | MIC range (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 95.9 | 3.5 | 0.6 | 256 | >1024 | 1-1024 |

| Cefoxitin | 99.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 512 | 1024 | 0.5-1024 |

| Ceftazidime | 25.0 | 3.5 | 71.5 | 0.25 | 256 | 0.125-256 |

| Cefepime | 16.3 | 6.4 | 77.3 | 0.25 | 32 | 0.125-256 |

| Meropenem | 8.1 | 1.7 | 90.1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.0125-64 |

| Gentamicin | 6.4 | 0.0 | 93.6 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.125-256 |

| Amikacin | 1.2 | 0.0 | 98.8 | 1 | 4 | 0.5-512 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 14.5 | 7.0 | 78.5 | 0.125 | 2 | 0.125-256 |

| Chloramphenicol | 16.3 | 15.1 | 68.6 | 8 | 256 | 1-1024 |

| Fosfomycin | 22.1 | 18.0 | 59.9 | 64 | 256 | 1-1024 |

| Colistin | 71.5 | 28.5 | 0.0 | 16 | 256 | 0.125-256 |

| Tigecycline | 3.5 | 19.8 | 76.7 | 1 | 4 | 0.125-256 |

| Tetracycline | 18.0 | 27.3 | 54.7 | 4 | 64 | 1-256 |

Distribution of resistance genes among ECC isolates.

A total of 80 antibiotic resistance genes (>80 similarity with the function characterized resistance genes) associated with 11 antimicrobial agent categories were identified among the genomes of all the isolates, such as aminoglycosides (aph(6)-Id, aac(6′)-IIc, aac(6′)-Ib, aph(3′’)-Ib, and aac(3)-Iia), beta-lactam (blaNDM-1, blaKPC-2, blaOXA-1, blaCTX-M-15, blaIMP-1, blaDHA-1, and blaSHV-12), fluoroquinolone (qnrE1 and qnrS2), fosfomycin (fosA3), macrolide (ereA), phenicol (catA2 and floR), polymyxin (mcr-10), rifampicin (arr-6), sulfonamide (sul2), tetracycline (tetA), and trimethoprim (dfrA12) (Fig. S1 in Supplemental File 1). The most prevalent resistance gene type belonged to β-lactams (30/80, 37.50%) followed by aminoglycosides (17/80, 21.25%).

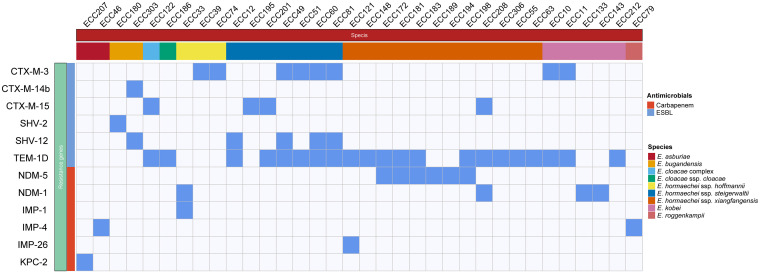

A large number (247) of β-lactamase genes were identified in the 172 genomes. The blaACT genes were the most dominant (145/247, 58.70%) followed by the blaTEM genes (21/247, 8.50%, blaTEM-1D only), while the blaKPC genes (1/247, 0.40%, blaKPC-2) had the lowest frequency. fosA genes were found in most strains (153/172, 88.95%), covering all species except E. hormaechei subsp. hormaechei, E. hormaechei subsp. oharae, and E. ludwigii (Fig. S1 in Supplemental File 1). Given the widespread use of β-lactam antibiotics in clinical settings, in this work, we gave more attention to resistance genes encoding beta-lactamases, especially those acquired horizontally (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. S1 in Supplemental File 1, the distribution of some inherent AmpCs differed among different species. For example, blaACT-2 and blaACT-3 were only present in E. asburiae, whereas blaACT-9, blaACT-12, and blaACT-6 were exclusively identified in E. kobei, E. ludwigii, and E. mori. Of note, ESBL genes and MBL genes were predominant among the horizontally acquired genes. ESBL genes were found in 26 isolates, with blaTEM-1D being the most prevalent (n = 18) followed by blaCTX-M-3 (n = 8), and blaSHV-12 (n = 5). Carbapenem-resistant genotypes were present in 14 strains, with blaNDM-5 being the most prevalent (n = 6) followed by blaNDM-1 (n = 4), blaIMP-4 (n = 2), blaIMP-1 (n = 1), blaIMP-26 (n = 1), and blaKPC-2 (n = 1). It was also interesting that among isolates carrying the ESBLs or carbapenem genes, only blaNDM-5 showed some species specificity, appearing only in E. hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis. Importantly, one isolate belonging to the E. hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii harbored two MBL genes, blaNDM-1 and blaIMP-1.

FIG 2.

Distributions of acquired β-lactamase genes in the 26 isolates. Blue and white squares represent the presence and absence of genes, respectively.

MLST analysis.

MLST analysis showed that these 172 ECC isolates were divided into 126 STs, including 62 novel STs (ST1497, ST1601, ST1647-1653, ST1655-1685, ST1687, ST1689-1708, and ST1711) (Table 1). Among these STs, the predominant epidemic type was ST78 (n = 7), followed by ST171 (n = 6) and ST414 (n = 5) (Table 1; Fig. S2 in Supplemental File 1).

Pan-genome analysis of E. hormaechei and E. kobei.

Because of the high frequency of the acquired resistance genes in the two species E. hormaechei and E. kobei, a pan-genome analysis was performed to determine the dynamics of the bacterial genomes. The results showed that a total of 2,932 core genes, 7,879 accessory genes (genes present in two or more genomes), and 8,629 unique genes (a gene specific to a single genome (13)) were found in the E. hormaechei strains. Similarly, there were 3,603 core genes, 3,577 accessory genes, and 4,216 unique genes among the E. kobei strains (Fig. S3 in Supplemental File 1).

The rarefaction curve of the two species revealed that as genomes were sampled, the number of pan-genome genes did not show a trend of saturation, which indicated that the pan-genome of the two species were open according to the Heaps’ law model. The tendency for an open status, to some extent, meant that species with a higher number of pangenome genes had a greater capacity to acquire exogenous genes. However, E. hormaechei showed a lower number of core genes but a higher number of accessory and unique genes than E. kobei, which might be due to the diversity of E. hormaechei strains, which included more (5) subspecies.

To further understand the functional differences of pangenome genes, Cluster of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG) functional classification of core genes, accessory genes, and unique genes of the two species was performed. The results indicated that the two species shared a highly similar COG category repartition of the core genomes, mainly associated with the functional classification of inorganic ion transport and metabolism, transcription, amino acid transport, and metabolism. Compared with the core genome, the unique and accessory genomes presented greater abundance in replication, recombination, and repair, which indicated that the functions of these genes are more likely to be associated with plasmid maintenance (14). Interestingly, there was a higher proportion of genes with unknown function (35.57% to 36.01%), indicating that the pan-genome genes of the two species have not been intensively studied yet.

Genetic environment of carbapenem-resistant genes.

Six carbapenemase genes were identified in 14 ECC isolates, including blaNDM-1, blaNDM-5, blaIMP-1, blaIMP-4, blaIMP-26, and blaKPC-2. As shown in Fig. S4A in Supplemental File 1, the genetic context of blaKPC-2 in the IncR plasmid pECC207-88 was consistent with that of another Enterobacter cloacae IncR plasmid, pHN84KPC (KY296104). However, the transposase of the Tn3 unit upstream of blaKPC-2 differed from the classical Tn1722-blaKPC-2-unit transposon in the Klebsiella pneumoniae IncR plasmid pKP048 (FJ628167). Although the flanks of blaKPC-2 were enwrapped by ISKpn6 and ISKpn27 in both pKP048 and pECC207-88, the transposon followed by ISKpn27 in pECC207-88 was an insertion sequence that shared 84% nucleotide similarity with ISEc63, a 4,473 bp element that belonged to the Tn3 family. Notably, similar ISEc63-like elements have also been reported in other Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with nonclassical transposon elements (15).

The genetic environments surrounding blaNDM-1 are shown in Fig. S4B in Supplemental File 1. Four plasmids carrying blaNDM-1 could be classified into different sequence types. The type A plasmid lacked the ISAba125 element upstream of IS5, and the genes downstream of groEL were different from those in the previously reported IncX3 plasmid pNDM-ECN49 (KP765744). The cutA1 gene of the type B plasmid was truncated by the insertion of IS26. Thus, the genes downstream of cutA1 changed greatly compared with the sequences of the type A plasmid. The transposase also exhibited a difference between IS3000 and ΔISAba125. Furthermore, similar to the type A plasmid, the sequence structure of type B lacked the ISAba125 element upstream of IS1 compared with the epidemic IncX3 plasmid pZHH-4 (CP059715). The genetic structure of the type C plasmid shared the highest similarity with the transposon Tn6460, which was composed of Tn6292 and a truncated Tn3000. However, compared with Tn6460, Tn6292 was inserted into the middle region of ΔTn3000 (dsbD gene) instead of the region downstream of ΔTn3000. Notably, no structure completely consistent with that of the type C plasmid was found in the NCBI nucleotide database. Six plasmids possessed the same genetic background of blaNDM-5 (IS3000-ISAba125-IS5-ΔISAba125-blaNDM-5-bleMBL-trpF-dsbC-ΔcutA1-IS26-umuD-ISKox3), which is the same as that of IncX3 plasmid pNDM_MGR194 (KF220657) from Klebsiella pneumoniae strain MGR-K194 isolated in India (Fig. S4C in Supplemental File 1).

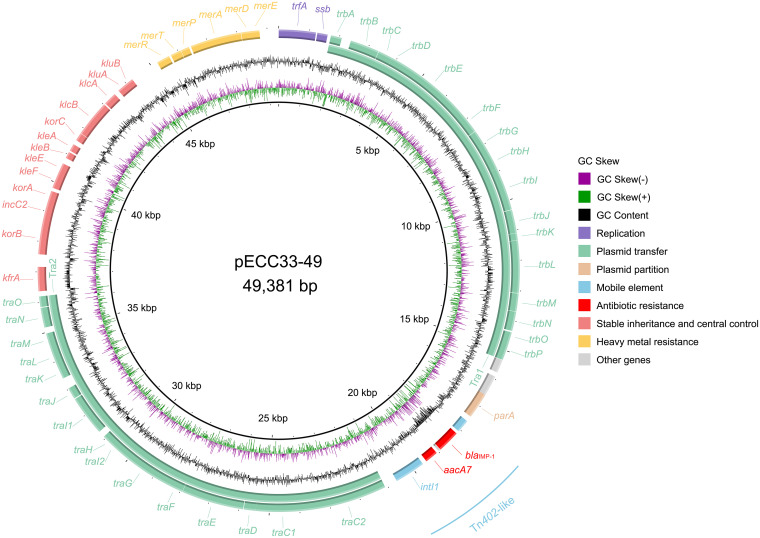

All of the IMP genes were located in class 1 integrons (Fig. S4D in Supplemental File 1). The gene cassette of the blaIMP-26-containing integron was blaIMP-26-ltrA-qacEΔ1-sul1, which was the same as that of IncHI2 plasmid pIMP26 from E. cloacae (MH399264). Two IncN plasmids (pECC46-54 and pECC79-52) carrying blaIMP-4 had a structurally similar genetic context except for the insertion of an ISSen4 between blaIMP-4 and ltrA. Moreover, the genes surrounding blaIMP-4 in these two plasmids were identical to IncN plasmids pIMP-HK1500 (KT989599) and pP10159-2 (MF072962), both from Citrobacter freundii. The blaIMP-1 gene in pECC33-49 was situated within a Tn402-like integron, which was atypical due to a lack of 3′-CS. A similar genetic structure of blaIMP-1 (intI1-aacA7-ΔorfE-blaIMP-1-ΔtniA) was also found in IncP-1β plasmid pA22732-IMP (KJ588780) from Achromobacter xylosoxidans. However, the orfE-like gene was truncated to only 64 bp in length.

Identification and characterization of an NDM-1- and IMP-1-coproducing ECC ECC33.

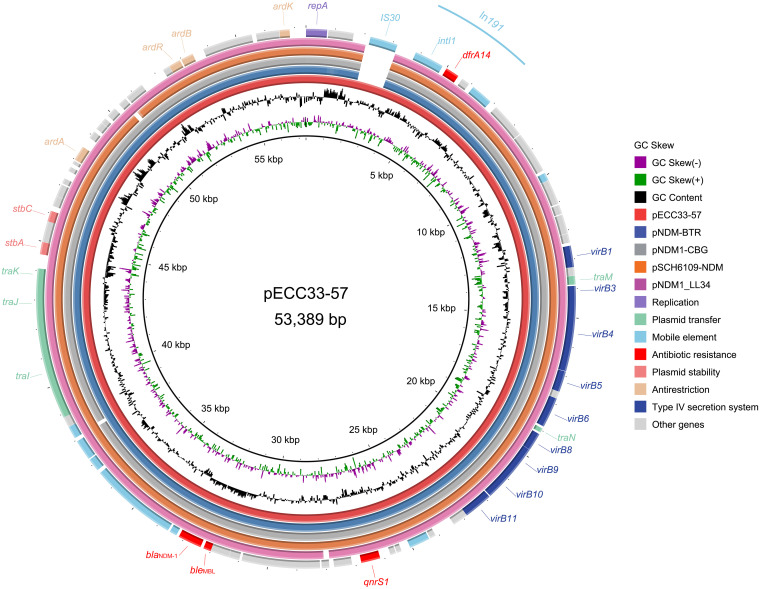

The isolate ECC33, harboring two MBLs (NDM-1- and IMP-1) and conferring high-level resistance to meropenem (MIC of 256 μg/mL), was isolated from the urine of an old patient who was diagnosed with urinary tract infection in a tertiary hospital in Zhejiang, China. The ANI result revealed that ECC33 shared the highest identity (99.05%) with E. hormaechei subsp. hormaechei ATCC 49162 (AFHR00000000). MLST showed that ECC33 belonged to ST78, which was thought to be a high-risk clone among both ESBL-producing ECC and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae complex (CREC) (16). The ECC33 genome consisted of a circular chromosome and two plasmids. The blaIMP-1 was carried on the IncP-1β plasmid pECC33-49, which encoded 56 open reading frames (ORFs) with a length of 49,381 bp, and the blaNDM-1 was carried on the IncN plasmid pECC33-57, which was 57,389 bp in length and contained 72 ORFs.

pECC33-57 carried several antimicrobial resistance genes (blaNDM-1, ble, qnrS1, and dfrA14) conferring resistance to β-lactams, bleomycin, quinolones, and trimethoprim. Sequence analysis indicated that pECC33-57 also carried different mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including one class 1 integron In191 (Fig. 3). Comparative genomic analysis revealed that pECC33-57 shared the highest sequence similarities with four blaNDM-1-carrying IncN plasmids, namely, pNDM1-CBG (CP046118.1; 97% coverage and 100% identity), pSCH6109-NDM (CP050859.2; 97% coverage and 99.95% identity), pNDM1_LL34 (CP025965.2; 97% coverage and 99.99% identity) and pNDM-BTR (KF534788.2; 98% coverage and 99.99% identity), especially true in the classical and highly conserved backbones of these plasmids (Fig. 3). Interestingly, compared with these four plasmids, one extra IS30 inserted upstream of In191 was observed in pECC33-57, which may be associated with the mobilization of In191.

FIG 3.

Genomic comparison of the plasmid pECC33-57 (red inner circle) with its close relatives. The ORFs of different gene functions are denoted by rectangles in various colors. Genes present in pECC33-57 but absent in the other plasmids are shown as blank spaces in the rings.

Only one antimicrobial resistance gene, blaIMP-1, located within a Tn402-like integron, was found in pECC33-49. An operon related to resistance to mercury (merEDAPTR) was also found in pECC33-49. Moreover, plasmid pECC33-49 contained two transfer-related regions, one consisting of 15 tra genes (traC to traO) and the other consisting of 16 trb genes (trbA to trbP) (Fig. 4). Notably, when searching for pECC33-49-like genomes (>80% coverage and >80 identity) in the NCBI database, none of the related genomes identified were from the Enterobacter cloacae complex. In contrast, we found four blaIMP-1-encoding IncP-1β plasmids from Achromobacter xylosoxidans (pA22732-IMP, 99.95% coverage and 99.98% identity; KJ588780.1), Morganella morganii (pNXM63-IMP, 98.76% coverage and 99.99% identity; MW150990.1), and Aeromonas caviae (pKAM345_1, 91.60% coverage and 99.93% identity; AP024949.1; pKAM339_2, 91.61% coverage and 99.93% identity; AP024942.1). Phylogenetic analysis of these five IncP-1β plasmids revealed that pECC33-49 has a close relationship with plasmid pNXM63-IMP (MW150990.1) from Morganella morganii (Fig. S5 in Supplemental File 1). This finding indicated that the pECC33-49-like plasmids were more likely to be transferred between bacterial species of different genera.

FIG 4.

Schematic map of pECC33-49. The ORFs are colored based on gene function classification. The circles represent (from outside to inside) the predicted coding sequences (CDS); GC content; GC skew; and scale in kilobase pairs.

DISCUSSION

ECC are common nosocomial pathogens ranking as the top three Enterobacteriaceae in healthcare-associated infections (3), which has attracted wide public attention. Nevertheless, the presence and emergence of multiple species/subspecies of ECC have led to diversity and complications at the taxonomic level. Moreover, it impedes the further understanding of the epidemiology and clinical significance of species/subspecies of ECC. Accurate identification of ECC species is extremely important. Previous studies have mainly classified ECC species by phenotype or hsp60 typing (2). With the rapid development of sequencing technology, genotypic classification methods, such as ANI, have higher accuracy and resolution. In this work, 172 ECC clinical isolates were collected from three hospitals in different cities in Zhejiang Province in southern China, and then further classified 160 into 9 species based on ANI analysis. E. hormaechei (45.14%) and E. kobei (13.71%) were the predominant species, and the high prevalence of E. hormaechei and E. kobei among ECC isolates was consistent with the findings of a previous study that investigated the characterization of ESBL-positive community-acquired ECC isolates from 31 hospitals in 12 provinces of China (6). Interestingly, because novel species recently described based on a computational analysis of sequenced Enterobacter genomes (4, 17), E. bugandensis and E. roggenkampii were also identified in this study, accounting for 7.56% and 8.72% of the isolates, respectively. However, due to the limited sequencing data available in public databases, 12 isolates without characterized species/subspecies references could only be clustered into 4 clades (L, O, P and T) according to the classification method described by Sutton et al. (4), and these isolates will be further analyzed and might be classified as novel species/subspecies.

One hundred and twenty-six STs, including 62 novel STs, were found among the 172 isolates, with ST78 (4.07%) and ST171 (3.49%) ranking first and second, respectively. This large number and a great variety of STs, especially with half of the STs in such a small population being novel, indicated the members of the ECC group might have been evolving in clinical settings. A similar phenomenon was observed in a multicenter study in which novel STs accounted for a significant proportion (87.50%) (18). ST78 and ST171 were the most prevalent STs among the isolates in this work. A previous study revealed that ST78 and ST171, as high-risk CREC clones, were widely distributed and had high epidemic potential (19). The potential drug-resistant outbreaks caused by these STs still need robust surveillance.

Almost all of the isolates (170/172; 98.86%) carried AmpC β-lactamase genes, with blaACT genes being the most dominant (58.70%), indicating that inducible ACT AmpC enzymes are conserved among ECCs. Intriguingly, the ACT type β-lactamase genes exhibited a certain species specificity. For instance, blaACT-2 and blaACT-3 were only present in E. asburiae, whereas blaACT-9, blaACT-12, and blaACT-6 exclusively occurred in E. kobei, E. ludwigii, and E. mori, respectively. DHA, the most prevalent plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase that might confer slight resistance to carbapenem (20), was found to be less abundant in the E. cloacae complex. Interestingly, compared to the previous findings that the blaNDM-1 gene was most prevalent among the carbapenem-resistant isolates found in northeastern (e.g., Liaoning Province) (21), southern (e.g., Guangdong Province), and northwestern (e.g., Ningxia) (22) regions, the CREC strains we found here were dominated by blaNDM-5 (6/14; 42.86%), which might be due to differences in antibacterial agents use in different regions of China, or may be caused by the limited number of strains we collected. Moreover, a higher frequency of other acquired β-lactamase genes, such as blaTEM, was observed in E. hormaechei and E. kobei isolates, indicating that the strains of the two species are more likely to spread and survive in hospital settings. Pan-genome analysis of the two species revealed that they possessed a greater capacity to acquire exogenous genes (23), which might partly explain the higher frequency of resistance genes in these species.

Notably, a strain named ECC33 harboring two MBL genes, blaNDM-1 and blaIMP-1, was identified in our study. To the best of our knowledge, although a previous study has reported an NDM-1 and IMP-1 co-expressing E. cloacae strain based on next-generation sequencing in Ningxia in northwest China (22), this is the first report of detailed characterization of NDM-1 and IMP-1 encoded on two plasmids, respectively, in an E. hormaechei isolate. MLST assigned this isolate to ST78, a high-risk clone among both ESBL-producing ECC and CREC (19). There is no doubt that the emergence of the ST78 clone harboring two MBLs increases the difficulty of clinical treatment. Interestingly, compared with the blaIMP-1-encoding plasmid pECC33-49 from ECC33, 4 similar plasmid sequences (from Achromobacter xylosoxidans, Morganella morganii, and Aeromonas caviae) with >91.0% coverage and >99.0% identity were found from genera other than the E. cloacae complex in the NCBI database. The diversity of the origins indicated that the pECC33-49-like plasmids are widely distributed in different species and may be captured by E. hormaechei through the high-frequency transfer of the recombinant plasmids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical strain collection.

A large number of isolates from patients with active disease were continuously collected from three districts (Wenzhou, Hangzhou, and Huzhou) in Zhejiang Province, China between 2019 and 2020. After genetic identification of isolates as strains of Enterobacter cloacae complex, a total of 172 clinical ECC isolates were obtained from three tertiary hospitals (100 strains from hospital A in Wenzhou, 64 strains from hospital B in Hangzhou, and 8 strains from hospital C in Huzhou) for further study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using the agar dilution method on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar plates supplemented with different concentrations of antibiotics. The test was repeated three times to ensure accuracy. The MICs were then interpreted following the breakpoint criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) for Enterobacteriaceae (24). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as the MIC reference strain for quality control. Those isolates which conferred resistance to meropenem were considered to be carbapenem resistance phenotypes. ESBL confirmation test was also performed according to the method recommended by CLSI and positive strains were considered to be ESBL positive phenotype.

Whole-genome sequencing and sequence analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted from each isolate using an AxyPrep bacterial genomic DNA miniprep kit (Axygen Scientific, Union City, CA, USA). The library with an average insert size of 400 bp was prepared using NEBNext Ultra II DNA library preparation kit, and genomic sequencing by the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (paired-end run; 2 × 150 bp) was performed at Shanghai Sunny Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Genomic sequencing was performed by the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. Sequence assembly was conducted de novo on Illumina short reads using SPAdes v.3.14.0 (25). The genomes of isolates carrying MBL genes were further sequenced by PacBio RS II instruments (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA). The PacBio data were first assembled using Canu v2.1 (26) and then the assembled genomes were corrected using Illumina HiSeq data via Pilon v1.23 (27). Gene annotation was performed using the Prokka annotation pipeline (28) and corrected via BLASTN (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome). Antimicrobial resistance genes were detected using ResFinder (29), and plasmid replicon types were identified using PlasmidFinder (30). MLST analysis was performed using the MLST database (http://pubmlst.org/ecloacae). The population evolutionary relationship of ST was analyzed using GrapeTree (https://enterobase.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html). Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) were identified using ISFinder (31) and INTEGRALL (32) with default parameters. Gene distribution was visualized using the ComplexHeatmap package in R (33). Core genes of E. cloacae complex genomes were constructed using kSNP (34) to call single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and the recombined regions within the core genome were detected using Gubbins v2.4.1 (35). The phylogenetic tree was visualized in ggtree package in R (36). Genetic context analysis was performed using BLASTN and visualized in genoplotR (37). The BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG) (38) tool was used to generate the circular maps of the plasmids pECC33-57 and pECC33-49.

Pangenome analysis and COG functional characterization.

Analysis of the pangenomes of two species (E. hormaechei and E. kobei) was carried out using Roary v3.13.0 (39). The rarefaction curve of pan-genomes and core-genomes of selected species was visualized via ggplot2 (40). COG categorization of each pan-genome was performed using EggNOG-mapper v 2.1.0 (41) with an E value < 1e−10, an identity higher than 40%, and a coverage higher than 70%.

Species identification using ANI.

Due to the diversity of the subspecies of the Enterobacter cloacae complex, average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis was performed for the isolates collected. The type strains used for the ANI analysis are listed in Table S1 in Supplemental File 1. The ANI analysis was computed using FastANI v1.31 (42), and a value >95% was used as the threshold for species definition.

Ethics approval.

Individual patient data were not involved, and only anonymous clinical residual samples during routine hospital laboratory procedures were used in this study. It was approved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Hospital, Zhejiang, China.

Data availability.

The complete nucleotide sequences of the chromosome and two plasmids (pECC33-49 and pECC33-57) of ECC33 in this work have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers CP098486, CP098487, and CP098488, respectively. The raw data of isolates collected in this study have also been submitted to the NCBI SRA database under the accession number PRJNA871306.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge all study participants and individuals who contributed to this study.

We declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Q.B., C.C., and W.P. conceived and designed the experiments. M.Z., Y.L., D.H., L.W., F.D., J.L., X.L., and K.L. performed the experiments. X.D., C.Y., and L.Z. performed the data analysis and interpretation. X.D., M.Z., Q.B., C.C., and W.P. drafted the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Project of Taizhou City, China (21ywb126), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LGF19H200003), the Science and Technology Project of Wenzhou City, China (N20210001), and Student Scientific and Technological Innovation Activity Plan and Xinmiao Talent Plan of Zhejiang Province (2022R474A013).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Cheng Cong, Email: 113246570@qq.com.

Wei Pan, Email: 25658507@qq.com.

Krisztina M. Papp-Wallace, Louis Stokes Cleveland Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center

REFERENCES

- 1.Annavajhala MK, Gomez-Simmonds A, Uhlemann AC. 2019. Multidrug-resistant enterobacter cloacae complex emerging as a global, diversifying threat. Front Microbiol 10:44. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mezzatesta ML, Gona F, Stefani S. 2012. Enterobacter cloacae complex: clinical impact and emerging antibiotic resistance. Future Microbiol 7:887–902. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davin-Regli A, Pages JM. 2015. Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae; versatile bacterial pathogens confronting antibiotic treatment. Front Microbiol 6:392. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton GG, Brinkac LM, Clarke TH, Fouts DE. 2018. Enterobacter hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii subsp. nov., Enterobacter hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis comb. nov., Enterobacter roggenkampii sp. nov., and Enterobacter muelleri is a later heterotypic synonym of Enterobacter asburiae based on computational analysis of sequenced Enterobacter genomes. F1000Res 7:521. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14566.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavda KD, Chen L, Fouts DE, Sutton G, Brinkac L, Jenkins SG, Bonomo RA, Adams MD, Kreiswirth BN. 2016. Comprehensive genome analysis of carbapenemase-producing enterobacter spp.: new insights into phylogeny, population structure, and resistance mechanisms. mBio 7:e02093-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02093-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou K, Yu W, Cao X, Shen P, Lu H, Luo Q, Rossen JWA, Xiao Y. 2018. Characterization of the population structure, drug resistance mechanisms and plasmids of the community-associated Enterobacter cloacae complex in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:66–76. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez A, Pereira MJ, Suarez JM, Poza M, Trevino M, Villalon P, Saez-Nieto JA, Regueiro BJ, Villanueva R, Bou G. 2011. Emergence in Spain of a multidrug-resistant Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolate producing SFO-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase. J Clin Microbiol 49:822–828. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01872-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guh AY, Bulens SN, Mu Y, Jacob JT, Reno J, Scott J, Wilson LE, Vaeth E, Lynfield R, Shaw KM, Vagnone PM, Bamberg WM, Janelle SJ, Dumyati G, Concannon C, Beldavs Z, Cunningham M, Cassidy PM, Phipps EC, Kenslow N, Travis T, Lonsway D, Rasheed JK, Limbago BM, Kallen AJ. 2015. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in 7 US communities, 2012–2013. JAMA 314:1479–1487. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Q, Liu Q, Han L, Sun J, Ni Y. 2010. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme KPC-2 and ArmA 16S rRNA methylase conferring high-level aminoglycoside resistance in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae in China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 66:326–328. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai W, Sun S, Yang P, Huang S, Zhang X, Zhang L. 2013. Characterization of carbapenemases, extended spectrum beta-lactamases and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacter cloacae in a Chinese hospital in Chongqing. Infect Genet Evol 14:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, Wu AW, Su DH, Lin YP, Chen DQ, Qiu YR. 2014. resistome analysis of Enterobacter cloacae CY01, an extensively drug-resistant strain producing VIM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase from China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6328–6330. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03060-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Qin S, Xu H, Xu L, Zhao D, Liu X, Lang S, Feng X, Liu HM. 2015. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1(NDM-1), the dominant carbapenemase detected in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae from Henan Province, China. PLoS One 10:e0135044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medini D, Donati C, Tettelin H, Masignani V, Rappuoli R. 2005. The microbial pan-genome. Curr Opin Genet Dev 15:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinha AK, Possoz C, Leach DRF. 2020. The roles of bacterial DNA double-strand break repair proteins in chromosomal DNA replication. FEMS Microbiol Rev 44:351–368. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuaa009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wozniak A, Figueroa C, Moya-Flores F, Guggiana P, Castillo C, Rivas L, Munita JM, Garcia PC. 2021. A multispecies outbreak of carbapenem-resistant bacteria harboring the blaKPC gene in a non-classical transposon element. BMC Microbiol 21:107. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02169-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Hayakawa K, Ohmagari N, Shimojima M, Kirikae T. 2013. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for characterization of Enterobacter cloacae. PLoS One 8:e66358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davin-Regli A, Lavigne JP, Pages JM. 2019. Enterobacter spp.: update on taxonomy, clinical aspects, and emerging antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 32:e00002-19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izdebski R, Baraniak A, Herda M, Fiett J, Bonten MJ, Carmeli Y, Goossens H, Hryniewicz W, Brun-Buisson C, Gniadkowski M, Mosar Wp WP, Groups WPS, MOSAR WP2, WP3 and WP5 Study Groups . 2015. MLST reveals potentially high-risk international clones of Enterobacter cloacae. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:48–56. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Simmonds A, Annavajhala MK, Wang Z, Macesic N, Hu Y, Giddins MJ, O’Malley A, Toussaint NC, Whittier S, Torres VJ, Uhlemann A-C. 2018. Genomic and geographic context for the evolution of high-risk carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae complex clones ST171 and ST78. mBio 9:e00542-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00542-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souna D, Amir AS, Bekhoucha SN, Berrazeg M, Drissi M. 2014. Molecular typing and characterization of TEM, SHV, CTX-M, and CMY-2 beta-lactamases in Enterobacter cloacae strains isolated in patients and their hospital environment in the west of Algeria. Med Mal Infect 44:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Tian S, Nian H, Wang R, Li F, Jiang N, Chu Y. 2021. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae complex in a tertiary Hospital in Northeast China, 2010–2019. BMC Infect Dis 21:611. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai Y, Chen C, Zhao M, Yu X, Lan K, Liao K, Guo P, Zhang W, Ma X, He Y, Zeng J, Chen L, Jia W, Tang YW, Huang B. 2019. High prevalence of metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae from three tertiary hospitals in China. Front Microbiol 10:1610. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diene SM, Merhej V, Henry M, El Filali A, Roux V, Robert C, Azza S, Gavory F, Barbe V, La Scola B, Raoult D, Rolain JM. 2013. The rhizome of the multidrug-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes genome reveals how new “killer bugs” are created because of a sympatric lifestyle. Mol Biol Evol 30:369–383. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CLSI. 2020. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th Edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. 2017. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res 27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, Cuomo CA, Zeng Q, Wortman J, Young SK, Earl AM. 2014. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bortolaia V, Kaas RS, Ruppe E, Roberts MC, Schwarz S, Cattoir V, Philippon A, Allesoe RL, Rebelo AR, Florensa AF, Fagelhauer L, Chakraborty T, Neumann B, Werner G, Bender JK, Stingl K, Nguyen M, Coppens J, Xavier BB, Malhotra-Kumar S, Westh H, Pinholt M, Anjum MF, Duggett NA, Kempf I, Nykasenoja S, Olkkola S, Wieczorek K, Amaro A, Clemente L, Mossong J, Losch S, Ragimbeau C, Lund O, Aarestrup FM. 2020. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Moller Aarestrup F, Hasman H. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. 2006. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 34:D32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moura A, Soares M, Pereira C, Leitao N, Henriques I, Correia A. 2009. INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes. Bioinformatics 25:1096–1098. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. 2016. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32:2847–2849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardner SN, Slezak T, Hall BG. 2015. kSNP3.0: SNP detection and phylogenetic analysis of genomes without genome alignment or reference genome. Bioinformatics 31:2877–2878. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Harris SR. 2015. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu G, Smith DK, Zhu H, Guan Y, Lam TT-Y. 2017. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol Evol 8:28–36. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guy L, Kultima JR, Andersson SG. 2010. genoPlotR: comparative gene and genome visualization in R. Bioinformatics 26:2334–2335. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alikhan NF, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA. 2011. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 12:402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, Holden MT, Fookes M, Falush D, Keane JA, Parkhill J. 2015. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wickham H. 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantalapiedra CP, Hernandez-Plaza A, Letunic I, Bork P, Huerta-Cepas J. 2021. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol Biol Evol 38:5825–5829. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain C, Rodriguez RL, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. 2018. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun 9:5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download spectrum.02160-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 3.2 MB (3.2MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The complete nucleotide sequences of the chromosome and two plasmids (pECC33-49 and pECC33-57) of ECC33 in this work have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers CP098486, CP098487, and CP098488, respectively. The raw data of isolates collected in this study have also been submitted to the NCBI SRA database under the accession number PRJNA871306.