ABSTRACT

Gram-negative bacteria are problematic for antibiotic development due to the low permeability of their cell envelopes. To rationally design new antibiotics capable of breaching this barrier, more information is required about the specific components of the cell envelope that prevent the passage of compounds with different physiochemical properties. Ampicillin and benzylpenicillin are β-lactam antibiotics with identical chemical structures except for a clever synthetic addition of a primary amine group in ampicillin, which promotes its accumulation in Gram-negatives. Previous work showed that ampicillin is better able to pass through the outer membrane porin OmpF in Escherichia coli compared to benzylpenicillin. It is not known, however, how the primary amine may affect interaction with other cell envelope components. This study applied TraDIS to identify genes that affect E. coli fitness in the presence of equivalent subinhibitory concentrations of ampicillin and benzylpenicillin, with a focus on the cell envelope. Insertions that compromised the outer membrane, particularly the lipopolysaccharide layer, were found to decrease fitness under benzylpenicillin exposure, but had less effect on fitness under ampicillin treatment. These results align with expectations if benzylpenicillin is poorly able to pass through porins. Disruption of genes encoding the AcrAB-TolC efflux system were detrimental to survival under both antibiotics, but particularly ampicillin. Indeed, insertions in these genes and regulators of acrAB-tolC expression were differentially selected under ampicillin treatment to a greater extent than insertions in ompF. These results suggest that maintaining ampicillin efflux may be more significant to E. coli survival than full inhibition of OmpF-mediated uptake.

IMPORTANCE Due to the growing antibiotic resistance crisis, there is a critical need to develop new antibiotics, particularly compounds capable of targeting high-priority antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. In order to develop new compounds capable of overcoming resistance a greater understanding of how Gram-negative bacteria are able to prevent the uptake and accumulation of many antibiotics is required. This study used a novel genome wide approach to investigate the significance of a primary amine group as a chemical feature that promotes the uptake and accumulation of compounds in the Gram-negative model organism Escherichia coli. The results support previous biochemical observations that the primary amine promotes passage through the outer membrane porin OmpF, but also highlight active efflux as a major resistance factor.

KEYWORDS: efflux pumps, Gram-negative bacteria, outer membrane

OBSERVATION

Gram-negative pathogens are naturally resistant to many compounds that effectively inhibit Gram-positive bacteria due to the low intrinsic permeability of their cell envelopes, making them a high priority for new antibiotic development (1). The Gram-negative cell envelope is complex. It notably comprises two membranes with distinct chemical characteristics and a network of active efflux pumps that typically display broad substrate specificities. The Gram-negative inner membrane is composed of phospholipids, whereas the outer membrane is polar, composed of a phospholipid inner leaflet and an outer leaflet of lipid A decorated with complex polysaccharides on its outer surface that vary considerably between strains and species. Detailed information linking specific components of the Gram-negative cell envelope to the exclusion or uptake of compounds with distinct physiochemical properties would aid in the rational design of new antibiotics that can penetrate and stay within Gram-negative cells. This study investigated the importance of a primary amine group in promoting the passage of β-lactam antibiotics in the model Gram-negative species Escherichia coli using a nontargeted genomic approach.

Ampicillin (AMP) and benzylpenicillin (PEN) are identical except for the presence of a primary amine group in AMP that is absent in PEN (Fig. 1, insets to panels A and B). This chemical feature was developed in the 1960s to improve PEN which is only clinically effective against Gram-positive species (2, 3). The primary amine has been identified as promoting compound accumulation in Gram-negatives (4), providing AMP with broad-spectrum antibiotic activity. It is known from genetic and biochemical studies that the primary amine in AMP improves its uptake through outer membrane (OM) porins, such as OmpF in E. coli (5, 6). However, other specific factors that may promote or impede the passage of β-lactam antibiotics across the Gram-negative cell envelope have not been comprehensively explored. Here, we applied Transposon Directed Insertion-site Sequencing (TraDIS) to identify the parts of the Gram-negative cell envelope that act to exclude or facilitate uptake of AMP and PEN, and thus infer their pathways of accumulation and the importance of the primary amine in AMP to overcome this barrier. More generally, this information will highlight specific elements of the barrier that could be targeted to potentiate compound entry.

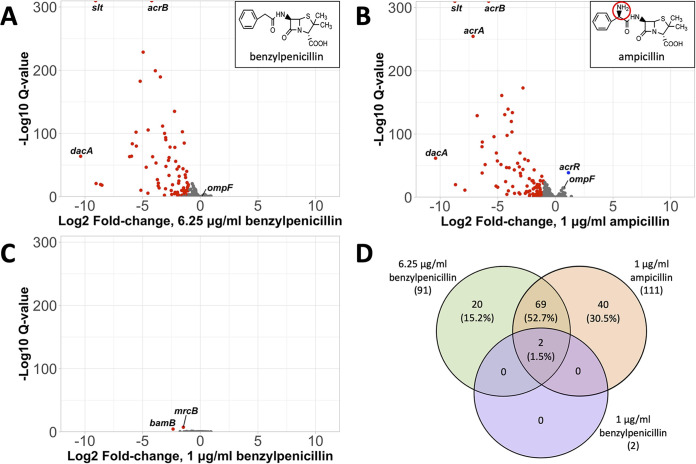

FIG 1.

Challenging BW25113 transposon library with subinhibitory concentrations of ampicillin and benzylpenicillin. Volcano plots of the fold change in transposon insertions in genes between antibiotic challenges and the untreated control are shown for 6.25 μg/mL PEN (A), 1 μg/mL AMP (B), and 1 μg/mL PEN challenges (C). Red datapoints are insertion changes with a ≥2-fold decrease and q.value <0.05, blue datapoints are insertion changes with a ≥2-fold increase and q.value <0.05, and gray datapoints are insertion changes with q.value ≥0.05. Inserts show the chemical structures for PEN (A) and AMP (B), with the primary amine group circled in red. (D) Venn diagram of overlap between genes with significant changes in insertion numbers in different challenge conditions.

TraDIS was performed using a high-density transposon mutant library of E. coli K-12 strain BW25113 (>400,000 unique mutants), constructed using a custom EzTn5 transposome according to previously described protocols (7, 8). The library was challenged with equivalent subinhibitory concentrations of AMP and PEN that resulted in near identical growth perturbations in the parental strain; 1 μg/mL AMP and 6.25 μg/mL PEN (~20% growth inhibition as determined by liquid media growth curves in Miller LB media), and the mutant profiles in the challenged libraries were compared to untreated controls using the TraDIS toolkit (9). Cells were sampled at stationary phase to ensure the effects of compound accumulation throughout the cell cycle, including during active growth phases, were reflected in mutant abundance (10). As AMP and PEN have the same antibacterial targets and modes of action (11), it was expected that considerable overlap between the significantly differentially selected genes would exist between the two treatment conditions, particularly for genes encoding their antibiotic targets and downstream systems that may compensate for target inhibition. Differences in mutant selection between the conditions could reflect alternative pathways of compound accumulation. An additional treatment of 1 μg/mL PEN was also included as a control to match AMP by media concentration.

Genes identified as important during antibiotic exposure were classified as having a +/-≥2-fold change in mutant abundance (as measured by change in relative transposon insertion frequency) between antibiotic-treated cells and untreated controls and q-value < 0.05. There were 111 such genes following 1 μg/mL AMP treatment, 91 following 6.25 μg/mL PEN treatment, and only 2 following 1 μg/mL PEN treatment (Fig. 1A,B; Data set S1). With the exception of acrR in the 1 μg/mL AMP treatment, all of these genes had a decrease in insertions following treatment, indicating that their disruption was deleterious to E. coli fitness under the conditions tested. The two significantly differentially selected genes in the 1 μg/mL PEN treatment were mrcB which encodes a bifunctional DD-transpeptidase/glycosyltransferase class 1 penicillin binding protein (PBP1A), a potential target of PEN, and bamB, encoding part of the β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM) complex, highlighting the importance of β-barrel proteins in the outer membrane and/or their products for the exclusion of PEN (Fig. 1C). Both genes were also significantly differentially selected under the two other antibiotic conditions tested.

Selection against insertions in β-lactam targets.

Approximately 54% of the significantly impacted genes were shared between the 1 μg/mL AMP and 6.25 μg/mL PEN treatments (Fig. 1D). To identify functional trends, the genes were assigned cluster of orthologous groups (COG) categories (Fig. 2). The most highly represented COG category was cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (M; Fig. 2). Many of the genes differentially selected by both antibiotics in this category involved in cell wall synthesis, including several penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), the targets of β-lactams. Indeed, mutations in dacA, encoding the major carboxypeptidase in E. coli PBP5, were the most highly selected against of any gene in both treatments. It has been suggested that PBP5, a redundant PBP, may act to sequester β-lactams away from essential PBPs, providing a shielding effect (12). This may explain why insertions in this PBP in particular were so detrimental to fitness under both treatments.

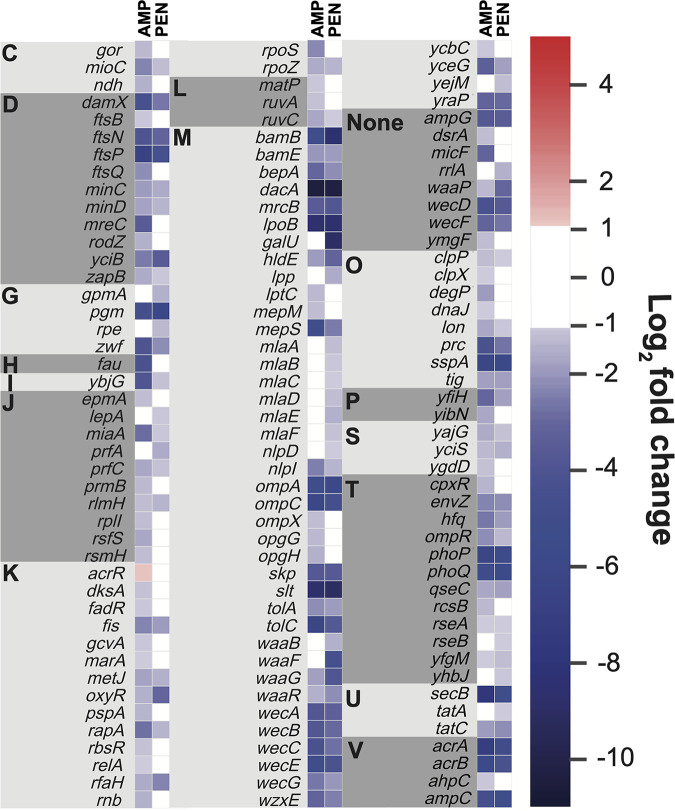

FIG 2.

Insertion frequency changes following ampicillin and benzylpenicillin treatment. Transposon insertion site numbers within each gene are presented as log2(FC), compared to the control group for ampicillin (AMP) and benzylpenicillin (PEN). Only genes with a q.value <0.05 and a fold change ≥abs(1) are shown. Genes are functionally grouped according to their COG categories: [C] Energy production and conversion, [D] Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning, [G] Carbohydrate transport and metabolism, [H] Coenzyme transport and metabolism, [I] Lipid transport and metabolism, [J] Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, [K] Transcription, [L] Replication, recombination and repair, [M] Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, [O] Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones, [P] Inorganic ion transport and metabolism, [S] Function unknown, [T] Signal transduction mechanisms, [U] Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport, [V] Defense mechanisms.

Insertions in other nonessential PBP genes such as mrcA and mrcB, encoding PBP1A and PBP1B, respectively, also had similar impacts on cell fitness under both the 1 μg/mL AMP and 6.25 μg/mL PEN treatments (although insertions in mrcA fell below the 2-fold threshold). lpoB, encoding an activator of McrB, was among the genes with the greatest decrease in insertions for either treatment. Insertions in several other genes involved in cell envelope production were also selected against by both treatments at similar levels, such as slt, which encodes a lytic transglycosylase thought to be involved in peptidoglycan quality control. Thus, many of the genes whose disruption most greatly decreased fitness under both antibiotics were either PBPs or genes that may compensate for PBP target inhibition, such as slt. The highly similar levels of selection against disruption of these genes supports the equivalence of the AMP and PEN concentrations tested.

Selection against insertions in LPS-related genes under benzylpenicillin treatment.

60% of genes uniquely affected by PEN treatment fell into the cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis COG category (M; Fig. 2). These genes were primarily involved in LPS synthesis and maintenance, such as yejM, which is implicated in lipid homeostasis; lpp, which anchors the OM to the cell wall; all genes making up the mla pathway (mlaA-F), which plays a role in maintaining LPS asymmetry; and the LPS core biosynthesis genes waaF and waaB. Although not uniquely affected, waaG and waaP were also both more negatively selected under PEN than AMP treatment. Mutations in both the waa and mla pathways compromise the OM and can significantly increase OM permeability and sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics like PEN (13, 14).

Another gene uniquely affected by PEN treatment was galU, which had one of the greatest decreases in insertions under PEN treatment. To examine the importance of galU for PEN tolerance, a targeted mutant (15) was examined. Deletion of galU resulted in a 2-fold reduction in PEN MIC (Fig. S1). GalU is involved in the production of UDP-d-glucose, a central precursor used in the synthesis of several OM components, including LPS, and is also essential in the galactose degradation pathway. Deletion of galU results in a compromised OM, as well as reduced levels of TolC (16), which may explain the impact of insertions in galU on cell fitness under PEN treatment.

The prominence of OM and particularly LPS-related genes among those most highly and, in some cases, uniquely detrimental to fitness under PEN treatment suggests that the LPS layer is crucial in preventing the uptake of PEN, aligning with the current understanding of poor PEN passage through OM porins in E. coli.

Functional trends among significantly affected genes were less apparent under AMP than PEN treatment. Overall, genes for which insertions were more negatively selected compared to PEN appeared to be involved in general stress responses rather than compound uptake. These included transcriptional regulators such as rpoS, which encodes the central regulator of the general stress response in E. coli and which has previously been observed to play a role in AMP resistance (17).

Another transcriptional regulator, acrR, which encodes a repressor of the AcrAB-TolC efflux system, had a significant increase in insertions under AMP treatment, and was the only gene with a significant increase in insertions >2-fold in any of the treatments tested according to the threshold used. Conversely, mutations in marA which encodes an activator of acrAB expression were negatively selected by AMP but not PEN treatment (Data set S1). The expression of marA is controlled by MarR in response to antibiotic and other stresses (18, 19). Insertions in the genes encoding AcrAB-TolC were all negatively selected under both AMP and PEN treatments (Fig. 2), albeit slightly more highly under AMP treatment, indicating that this system is important for the efflux of both compounds. This was supported by MIC assays which showed a 2-fold decrease in PEN MIC in an acrA deletion strain, compared to a 4-fold decrease in AMP MIC (Fig. S1).

Previous work has suggested that PEN may be a better substrate of AcrAB-TolC in E. coli than AMP (20). This may explain why AMP would impose higher selective pressure for the inactivation of the acrR repressor gene and maintenance of the marA activator gene than PEN, as a higher level of acrAB expression may compensate for lower levels of AMP transport by this pump. Alternatively, PEN may be better able to promote acrAB expression than AMP and thus reduce selective pressure for mutations that increase its expression. Indeed, PEN has a higher membrane permeability than AMP and thus greater potential to diffuse into the cytoplasm where it could interact with cytoplasmic regulators like AcrR to relieve translational repression of acrAB (20, 21). To investigate this possibility, qRT-PCR was performed to examine acrAB expression in wild-type cells treated with AMP and PEN at concentrations equivalent to those used in this assay (22). These experiments did not show a clear change in expression for these genes for either antibiotic treatment (data not shown). Another possible reason for selective pressure on acrR and marA under AMP selection could be the roles of these regulators in controlling other genes, such as ompF.

The porin OmpF has previously been shown to be important for the uptake of ampicillin into the E. coli periplasm. The ompF gene had only a slight increase in insertions under AMP treatment (less than 2-fold) and no significant change under PEN treatment. These results are consistent with the greater capacity of AMP to pass through OmpF compared to PEN, but suggest that under the conditions tested maintaining AMP efflux via AcrAB-TolC is more beneficial to cells than disrupting uptake via OmpF. Due to the role of OmpF in mediating the OM passage of other small molecules important to cell fitness, its inactivation may have an overall negative fitness effect. This is supported by the decreased growth rate of BW25113 ΔompF compared to wild-type (Fig. S2). However, there is evidence of selection for reduced ompF expression via regulatory mutations, particularly under AMP selection. For example, selection against insertions in cpxR, which encodes the response regulator of the CpxR/CpxA two-component regulatory system, was observed after AMP but not PEN treatment. Phosphorylated CpxR has been shown to repress expression of ompF and so its maintenance could reduce ompF expression levels (23). Conversely, mutations in the cognate sensor kinase gene cpxA have been shown to increase ompF expression in the presence of acetyl phosphate due to increased levels of phosphorylated CpxR (23). Selection for insertions in cpxR was observed under AMP, but not PEN, exposure. Further, insertions in the small RNA micF, which inhibits ompF expression (24, 25), were strongly selected against only under AMP treatment. micF may also be repressed by AcrR and activated by MarA (26, 27). This could therefore provide an alternate explanation for selection for insertions in acrR and against insertions in marA under AMP treatment. Such insertions could lead to reduced ompF expression. Therefore, there may have been stronger selection for reduced expression of ompF, rather than its complete inactivation under AMP selection.

Previous investigations into the role of the primary amine in ampicillin accumulation in Gram-negatives have primarily focused on how this chemical feature affects compound uptake. The significance of this altered uptake efficiency in improving accumulation is supported by this study. Collectively, these results suggest that unlike PEN, compromising the LPS layer does not appear to have a drastic impact on cell survival in AMP. This is to be expected as AMP is able to enter cells through OmpF-mediated uptake. However, the potential effects of the primary amine on compound efflux and the contribution of this to changes in overall levels of accumulation have been understudied. These findings suggest that maintaining AMP efflux via AcrAB-TolC is of comparable importance to E. coli survival as inhibiting uptake. These results highlight the potential for TraDIS to guide investigations of antibiotic accumulation into Gram-negative bacteria.

Data availability.

TraDIS sequence reads are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and can be accessed using the NCBI BioProject accession PRJNA875563.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship to K.A.H (FT180100123). We thank Liam D. H. Elbourne (Macquarie University) for assistance with the Bio-Tradis bioinformatics pipeline. We thank Silas H. W. Vick (Norwegian University of Life Sciences) for assistance with heatmap figures.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Karl A. Hassan, Email: karl.hassan@newcastle.edu.au.

Philip N. Rather, Emory University School of Medicine

Jessica Blair, University of Birmingham.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, Pulcini C, Kahlmeter G, Kluytmans J, Carmeli Y, Ouellette M, Outterson K, Patel J, Cavaleri M, Cox EM, Houchens CR, Grayson ML, Hansen P, Singh N, Theuretzbacher U, Magrini N, WHO Pathogens Priority List Working Group . 2018. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown DM, Acred P. 1961. Penbritin—A new broad-spectrum antibiotic. Br Med J 2:197–198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5246.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acred P, Brown DM, Turner DH, Wilson MJ. 1962. Pharmacology and chemotherapy of ampicillin—A new broad-spectrum penicillin. Br J Pharmacol Chemother 18:356–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1962.tb01416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter MF, Drown BS, Riley AP, Garcia A, Shirai T, Svec RL, Hergenrother PJ. 2017. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature 545:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nature22308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harder KJ, Nikaido H, Matsuhashi M. 1981. Mutants of Escherichia coli that are resistant to certain beta-lactam compounds lack the ompF porin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 20:549–552. doi: 10.1128/AAC.20.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshimura F, Nikaido H. 1985. Diffusion of beta-lactam antibiotics through the porin channels of Escherichia coli K-12. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 27:84–92. doi: 10.1128/AAC.27.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langridge GC, Phan MD, Turner DJ, Perkins TT, Parts L, Haase J, Charles I, Maskell DJ, Peters SE, Dougan G, Wain J, Parkhill J, Turner AK. 2009. Simultaneous assay of every Salmonella Typhi gene using one million transposon mutants. Genome Res 19:2308–2316. doi: 10.1101/gr.097097.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alquethamy SF, Adams FG, Maharjan R, Delgado NN, Zang M, Ganio K, Paton JC, Hassan KA, Paulsen IT, McDevitt CA, Cain AK, Eijkelkamp BA. 2021. The molecular basis of acinetobacter baumannii cadmium toxicity and resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e01718-21. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01718-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barquist L, Mayho M, Cummins C, Cain AK, Boinett CJ, Page AJ, Langridge GC, Quail MA, Keane JA, Parkhill J. 2016. The TraDIS toolkit: sequencing and analysis for dense transposon mutant libraries. Bioinformatics 32:1109–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whittle EE, McNeil HE, Trampari E, Webber M, Overton TW, Blair JMA. 2021. Efflux impacts intracellular accumulation only in actively growing bacterial cells. mBio 12:e0260821. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02608-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kocaoglu O, Carlson EE. 2015. Profiling of β-lactam selectivity for penicillin-binding proteins in Escherichia coli strain DC2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2785–2790. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04552-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkar SK, Chowdhury C, Ghosh AS. 2010. Deletion of penicillin-binding protein 5 (PBP5) sensitises Escherichia coli cells to β-lactam agents. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malinverni JC, Silhavy TJ. 2009. An ABC transport system that maintains lipid asymmetry in the gram-negative outer membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:8009–8014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903229106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Wang J, Ren G, Li Y, Wang X. 2015. Influence of core oligosaccharide of lipopolysaccharide to outer membrane behavior of Escherichia coli. Mar Drugs 13:3325–3339. doi: 10.3390/md13063325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genevaux P, Bauda P, DuBow MS, Oudega B. 1999. Identification of Tn10 insertions in the rfaG, rfaP, and galU genes involved in lipopolysaccharide core biosynthesis that affect Escherichia coli adhesion. Arch Microbiol 172:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s002030050732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deter HS, Hossain T, Butzin NC. 2021. Antibiotic tolerance is associated with a broad and complex transcriptional response in E. coli. Sci Rep 11:356–369. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85509-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alekshun MN, Levy SB. 1999. Alteration of the repressor activity of MarR, the negative regulator of the Escherichia coli marRAB locus, by multiple chemicals in vitro. J Bacteriol 181:4669–4672. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.15.4669-4672.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen SP, Levy SB, Foulds J, Rosner JL. 1993. Salicylate induction of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli: activation of the mar operon and a mar-independent pathway. J Bacteriol 175:7856–7862. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7856-7862.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kojima S, Nikaido H. 2013. Permeation rates of penicillins indicate that Escherichia coli porins function principally as nonspecific channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:E2629–E2634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310333110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li XZ, Ma D, Livermore DM, Nikaido H. 1994. Role of efflux pump(s) in intrinsic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: active efflux as a contributing factor to beta-lactam resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 38:1742–1752. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.8.1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brzoska AJ, Hassan KA. 2014. Quantitative PCR for Detection of mRNA and gDNA in Environmental Isolates, p 25–42. In Paulsen IT, Holmes AJ (ed), Environmental microbiology: methods and protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batchelor E, Walthers D, Kenney LJ, Goulian M. 2005. The Escherichia coli CpxA-CpxR envelope stress response system regulates expression of the porins ompF and ompC. J Bacteriol 187:5723–5731. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5723-5731.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen J, Forst SA, Zhao K, Inouye M, Delihas N. 1989. The function of micF RNA: micF RNA is a major factor in the thermal regulation of OmpF protein in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 264:17961–17970. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)84666-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deighan P, Free A, Dorman CJ. 2000. A role for the Escherichia coli H-NS-like protein StpA in OmpF porin expression through modulation of micF RNA stability. Mol Microbiol 38:126–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodionov DA, Gelfand MS, Mironov AA, Rakhmaninova AB. 2001. Comparative approach to analysis of regulation in complete genomes: multidrug resistance systems in gamma-proteobacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 3:319–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen SP, McMurry LM, Levy SB. 1988. marA locus causes decreased expression of OmpF porin in multiple-antibiotic-resistant (Mar) mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 170:5416–5422. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5416-5422.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Set S1. Download spectrum.03593-22-s0001.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.8 MB (871.4KB, xlsx)

Supplemental material. Download spectrum.03593-22-s0002.pdf, PDF file, 0.2 MB (248.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

TraDIS sequence reads are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and can be accessed using the NCBI BioProject accession PRJNA875563.