ABSTRACT

Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria is the most urgent global threat to public health, with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-E. coli) being one of the most documented examples. Nonetheless, the ESBL-E. coli transmission relationship among clinical sites and chicken farms remains unclear. Here, 408 ESBL-E. coli strains were isolated from hospitals and chicken farms in Sichuan Province and Yunnan Province in 2021. We detected blaCTX-M genes in 337 (82.62%) ESBL-E. coli strains. Although the isolation rate, prevalent sequence type (ST) subtypes, and blaCTX-M gene subtypes of ESBL-E. coli varied based on regions and sources, a few strains of CTX-ESBL-E. coli derived from clinical sites and chicken farms in Sichuan Province displayed high genetic similarity. This indicates a risk of ESBL-E. coli transmission from chickens to humans. Moreover, we found that the high-risk clonal strains ST131 and ST1193 primarily carried blaCTX-M-27. This indicates that drug-resistant E. coli from animal and human sources should be monitored. As well, the overuse of β-lactam antibiotics should be avoided in poultry farms to ensure public health and build an effective regulatory mechanism of “farm to fork” under a One Health perspective.

IMPORTANCE Bacterial drug resistance has become one of the most significant threats to human health worldwide, especially for extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing E. coli (ESBL-E. coli). Timely and accurate epidemiological surveys can provide scientific guidance for the adoption of treatments in different regions and also reduce the formation of drug-resistant bacteria. Our study showed that the subtypes of ESBL-E. coli strains prevalent in different provinces are somewhat different, so it is necessary to individualize treatment regimens in different regions, and it is especially important to limit and reduce antibiotic use in poultry farming since chicken-derived ESBL-E. coli serves as an important reservoir of drug resistance genes and has the potential to spread to humans, thus posing a threat to human health. The use of antibiotics in poultry farming should be particularly limited and reduced.

KEYWORDS: ESBL-E. coli, bla CTX-M , virulence factor, chicken farm, hospital

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial infectious diseases have presented a significant challenge to clinical treatment and animal breeding practices, with Escherichia coli infections being the most prevalent (1). A 2019 report on the global survey of bacterial resistance indicated that E. coli is the leading cause of mortalities as a result of bacterial resistance (2). Bacterial resistance is a significant global challenge facing humans and animals; further, it is one of the most important clinical issues in world public health. Based on its strategy against antibiotic resistance, the World Health Organization (WHO) has selected seven antibiotic-resistant priority pathogens, including third-generation-cephalosporin (3GC)-resistant E. coli, which produces extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) (3). ESBL-producing E. coli (ESBL-E. coli) is commonly isolated from animals and humans and even in environments with little or no human activity (4, 5). Further, the overuse of antibiotics exacerbates the development of ESBL-E. coli strains, which often result in antibiotic treatment failure and limit clinical and animal drug use. Studies have shown that ESBL-E. coli is resistant to penicillin, aminopenicillin, and cephalosporins, including the approved veterinary drugs 3GC ceftiofur and cephalosporin and the fourth-generation cephalosporins (6). Humans and animals are closely related based on the One Health perspective. Long-term use of antibiotics in animals causes the development of bacterial resistance in animals, and in turn, these resistant bacteria may directly or indirectly transmit drug resistance genes to humans. This suggests that improving animal health promotes human health.

Several studies indicate that chickens are an important reservoir of ESBL genes, attracting significant global concern. ESBL-E. coli causes infection in broilers and layers, which is a critical contaminant in retail chicken meat. As a principal major source of protein, chicken is one of the largest global meat sources, with extensive consumption (7). The poultry farming industry is one of the fastest-growing industries across the globe. Many studies have identified antibiotic residues in poultry, potentially contributing to the development of resistance in human pathogens (8). Under the “farm to fork” strategy, antibiotic use in animals has been banned or reduced globally; this has resulted in a reduced prevalence rate of ESBL-E. coli derived from animals (9–11). Nonetheless, antibiotics are still the predominant therapeutic intervention for bacterial infectious diseases. Reports indicate that the overall use of antibiotics will gradually increase in the next decade, and 73.7% of them will be used in livestock (12, 13). The extensive use of antibiotics in animal farming has increased the proliferation of drug-resistant bacteria, which can be transmitted to humans via the food chain, water, or air.

The prevalence of β-lactam resistance derived from chicken farms significantly varies between countries and regions. For instance, the β-lactam resistance rate of E. coli derived from chickens in northern India is 49% (14), whereas the cefotaxime resistance rate of E. coli derived from chickens in Bangladesh is 78.1% (15). Also, studies have shown that the prevalence characteristics of β-lactam resistance vary in different specific regions of a country. For example, the cefotaxime resistance rate of E. coli isolated from chicken farms in different regions of South Korea ranged between 17.5% and 51.4% (16). Notably, blaCTX-M is the most prevalent β-lactam resistance gene in ESBL-E. coli (17), and CTX-ESBL-E. coli has been isolated from humans and animals across the globe (18). So far, over 200 subtypes of blaCTX-M have been identified, and the prevalent subtypes vary in different regions and sources. For instance, blaCTX-M-1 is the dominant resistance gene in ESBL-E. coli isolated from cattle in Germany, whereas blaCTX-M-15 is the dominant resistance gene in cattle in England (19). Moreover, studies indicate that blaCTX-M-1 is the dominant resistance gene in ESBL-E. coli isolated from farmed animals in Europe, whereas blaCTX-M-15 is predominant in the United States (20, 21). The blaCTX-M-14 gene is less prevalent in Europe; however, it is prevalent in poultry, animals, and humans in Asia (22). As such, the epidemiological investigation of blaCTX-M is complex.

The majority of E. coli strains are intestinal commensals in humans and animals. Nevertheless, some clonal strains with a high risk of pathogenicity have been discovered, which cause multiple infectious diseases and even death. The extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) ST131 belongs to the high-risk clonal subgroups, which carry several virulence genes and cause severe extraintestinal infections, including bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and neonatal meningitis. Of note, blaCTX-M-15 is the dominant resistance gene in E. coli ST131, originally identified in Canada, France, Switzerland, Portugal, Spain, Kuwait, Lebanon, India, and South Korea (23, 24) and presently having a global distribution trend (25). Unlike the non-ST131 E. coli, E. coli ST131 has a larger number of ExPEC-associated virulence factor genes. Moreover, E. coli ST131 effectively colonizes the intestine, bladder, and kidney of humans and food animals, including chickens and wild birds (26–29). Since ST131 carries numerous virulence factor genes and β-lactam resistance genes, once it is widely distributed in poultry, it causes treatment failure and huge economic losses to the poultry farming industry, posing a significant threat to human health.

Although transmission of pathogenic bacteria from poultry to humans has been reported, whether bacterial resistance can spread from poultry to humans remains unclear (30). ESBL-E. coli is widespread, but whether there is a clonal transmission relationship between ESBL-E. coli isolates derived from clinical sites and chicken farms is unclear. Therefore, it is important to analyze the sources of ESBL-E. coli isolates and their drug resistance genes to explore the transmission relationship between ESBL-E. coli isolates derived from humans and chickens from the perspective of One Health. In this study, we isolated and analyzed the prevalence of ESBL-E. coli derived from clinical sites and chicken farms in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces of China to understand the differences in bacterial resistance between different sources and provide epidemiological evidence of β-lactam resistance. Therefore, our findings will provide recommendations for poultry breeding and medical clinical interventions, as well as mitigation strategies for antibiotic resistance and its effects.

RESULTS

Isolation of CTX-ESBL-E. coli.

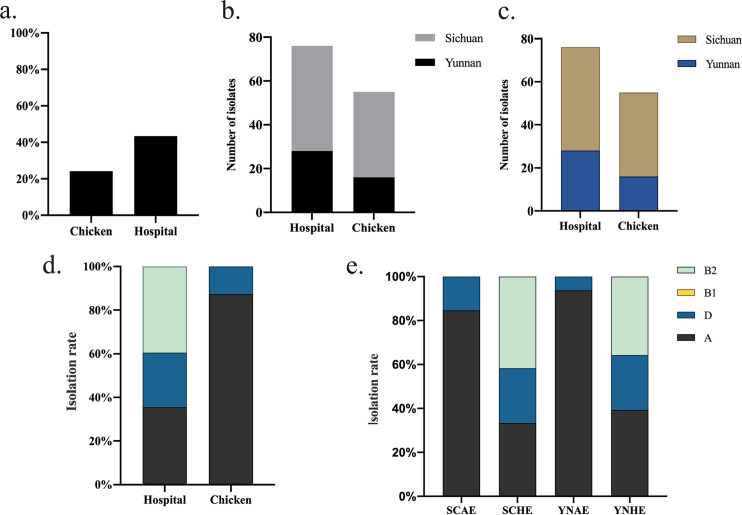

A total of 1,038 E. coli strains were isolated in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces from January to September 2021, i.e., 594 strains isolated from chicken farms (404 strains from Sichuan Province and 190 strains from Yunnan Province) and 444 clinical isolates (100 strains from Sichuan Province and 344 strains from Yunnan Province). Among these, 408 isolates were identified as ESBL-E. coli, accounting for 39.3% of the total isolates, including 204 isolates from chicken farms (151 strains from Sichuan Province and 53 strains from Yunnan Province) and 204 clinical isolates (48 strains from Sichuan Province and 156 strains from Yunnan Province). blaCTX-M ESBL genes were detected, and 337 (82.62%) ESBL-E. coli isolates carried blaCTX-M genes, including 144 isolates from chicken farms (107 strains from Sichuan Province and 37 strains from Yunnan Province) and 193 clinical isolates (48 strains from Sichuan Province and 145 strains from Yunnan Province). The detection rate of CTX-ESBL-E. coli in chicken farm-derived isolates was 24.24% and in clinical isolates was 43.47% (Fig. 1a). The clinical detection rate of CTX-ESBL-E. coli was higher in Sichuan Province (48%, 48/100) than in Yunnan Province (42.15%, 145/344). The detection rate of chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli in Sichuan Province (26.49%, 107/404) was also higher than that in Yunnan Province (19.47%, 37/190) (Fig. 1b). Finally, 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates (55 strains isolated from a chicken farm and 76 clinical isolates) with higher levels of resistance to cefotaxime (>128 μg/mL) were chosen (Fig. 1c) based on susceptibility testing results and used for whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of CTX-ESBL-E. coli. (a) Isolation rate of CTX-ESBL-E. coli in chicken farm-derived isolates and clinical isolates. (b) Isolation rate of CTX-ESBL-E. coli in chicken farm-derived isolates and clinical isolates in Sichuan Province and Yunnan Province. SCAE and YNAE indicate the chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli in Sichuan Province and Yunnan Province, respectively, SCHE and YNHE indicate the clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli in Sichuan Province and Yunnan Province, respectively. (c) Distribution of 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates used for whole-genome sequencing. (d and e) Isolation rates of four phylogenetic groups of 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates.

Determining the phylogenetic groups of E. coli strains.

Phylogenetic analyses indicated that E. coli strains fell into four primary phylogenetic groups (A, B1, B2, and D) with various pathogenicities. Strong pathogenicity was found in E. coli in the B2 and D groups, whereas weak pathogenicity was found in E. coli in the B1 group. The A group relates to animal and human gut commensals. Phylogroup analysis of the 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates discovered that 57.25% (48 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from chicken farms and 27 clinical isolates) were classified in the A group, 19.85% (7 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from chicken farms and 19 clinical isolates) were classified in the D group, and 22.9% (30 clinical isolates) were classified in the B2 group with the strongest pathogenicity (Fig. 1d). These results show that the clinically isolated CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains are more pathogenic than chicken farm-derived isolates. The isolation rate of pathogenic clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli was higher in Sichuan Province (66.67%, 32/48) than in Yunnan Province (60.71%, 17/28). However, the isolation rate of chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli classified in the D group from Sichuan Province was 15.38% (6/39), which was significantly higher than that from Yunnan Province at 6.25% (1/16) (Fig. 1e). In addition, all 30 CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains in the B2 group were isolated from hospitals, illustrating the strong pathogenic properties of the clinically isolated CTX-ESBL-E. coli. Nevertheless, 20% of CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates derived from chicken farms belong to the D group with specific pathogenicity. Avian-pathogenic E. coli was reported to transmit virulence factors to pathogenic E. coli outside the intestinal tract. Thus, continuous surveillance of pathogenic E. coli from different sources is the key to understanding potential transmission routes between animals and humans (31).

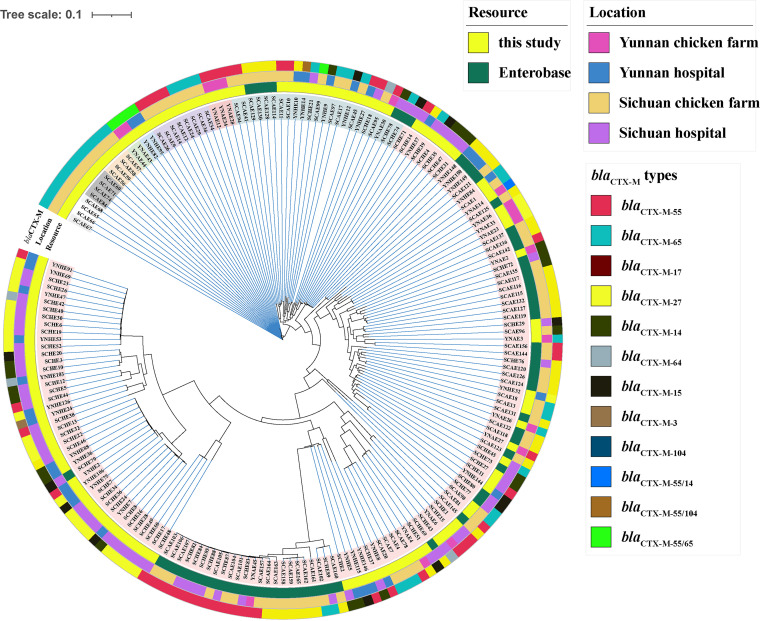

SNP evolutionary analysis.

A total of 63 CTX-ESBL-E. coli genome sequences from Yunnan and Sichuan provinces were downloaded from the EnteroBase database and were combined with 131 isolated CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains to construct a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) evolution tree (Fig. 2 and Table S2). SNP evolution analysis showed that the minimum number of SNPs was 0 and the maximum number of SNPs was 55,630; 87/131 strains had high similarity to strains in the EnteroBase database. A threshold of 5 SNPs among isolates was considered a clonal relationship, and the isolates were likely to have an epidemiological relationship. Figure 2 illustrates a higher similarity in the clinically isolated CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains from two provinces than in the CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains derived from chicken farms. Similarly, a higher similarity was also noted between CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains derived from chicken farms in two provinces; we also found strains of the same clone. Moreover, a few clinical and chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from Sichuan Province demonstrated genetic similarity (Table S2). Although significant SNP differences between CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from humans and chicken farms were observed, we noted a high genetic similarity in human and chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates in the same region. This indicates that animal-human transmission of drug-resistant isolates easily occurs within the same region.

FIG 2.

Single nucleotide polymorphism evolutionary analysis of CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates. The SNP evolution tree was created with CGE CSI Phylogeny 1.4, which was observed using the Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL v6, https://itol.embl.de/). The genome sequence of E. coli C600 (EC600, GenBank accession no. CP031214.1) was used as a reference.

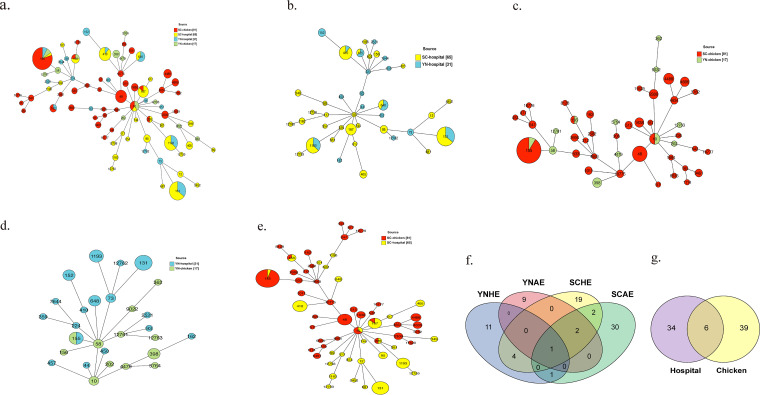

MLST analyses.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis of 194 isolates (Table S3) was performed and revealed significant diversity among these isolates. Notably, 78 sequence types (STs) were shared in 194 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates (Fig. 3a). ST155 (25 strains), ST131 (18 strains), ST1193 (11 strains), ST410 (9 strains), and ST48 (7 strains) were the dominant STs. A total of 32 STs were categorized in clinically isolated ESBL- E. coli (Fig. 3b), with ST131, ST410, and ST1193 being the predominant STs. A total of 24 STs were classified in the chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates (Fig. 3c), with ST155 and ST48 being the dominant STs. No other cross-STs were present in both clinical and chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates in Yunnan Province, except ST155 (Fig. 3d), whereas ST156, ST155, ST10, ST167, and ST226 were present in both clinical and chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates in Sichuan Province (Fig. 3e). The dominant ST of clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli was ST131, followed by ST1193, whereas ST155 was the dominant ST of chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli. In contrast, only ST155 E. coli was distributed in four sources (Fig. 3f). Six STs (ST162, ST156, ST10, ST155, ST167, and ST226) in chicken farm- and clinical site-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates (Fig. 3g) were found, suggesting that these six STs of E. coli are likely to spread between humans and chicken farms at a higher risk. The ubiquitous presence of ST155 E. coli distributed in four sources indicates the sequence type’s transmission benefits. In total, ST155 was the predominant ST in two provinces, followed by ST131. ST1193 and ST410 were found only in clinical isolates, whereas ST48 was found only in chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli in Sichuan Province. The above findings illustrate that chicken farm-derived and clinical isolates of CTX-ESBL-E. coli exhibit a certain risk of cross-transmission, especially in the same area. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a comprehensive prevalence survey of CTX-ESBL-E. coli in the respective areas. Additionally, we discovered 6 novel STs (Tables S4 and S5), of which 2 were in chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates (ST12761 and ST12763), whereas 4 were in clinical site-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates (ST12758, ST12759, ST12760, and ST12762).

FIG 3.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on multilocus sequence typing analyses of CTX-ESBL-E. coli. (a) ST distribution of CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates. (b to e) ST distribution of CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from different regions and sources. (f and g) Number of shared STs in the CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates.

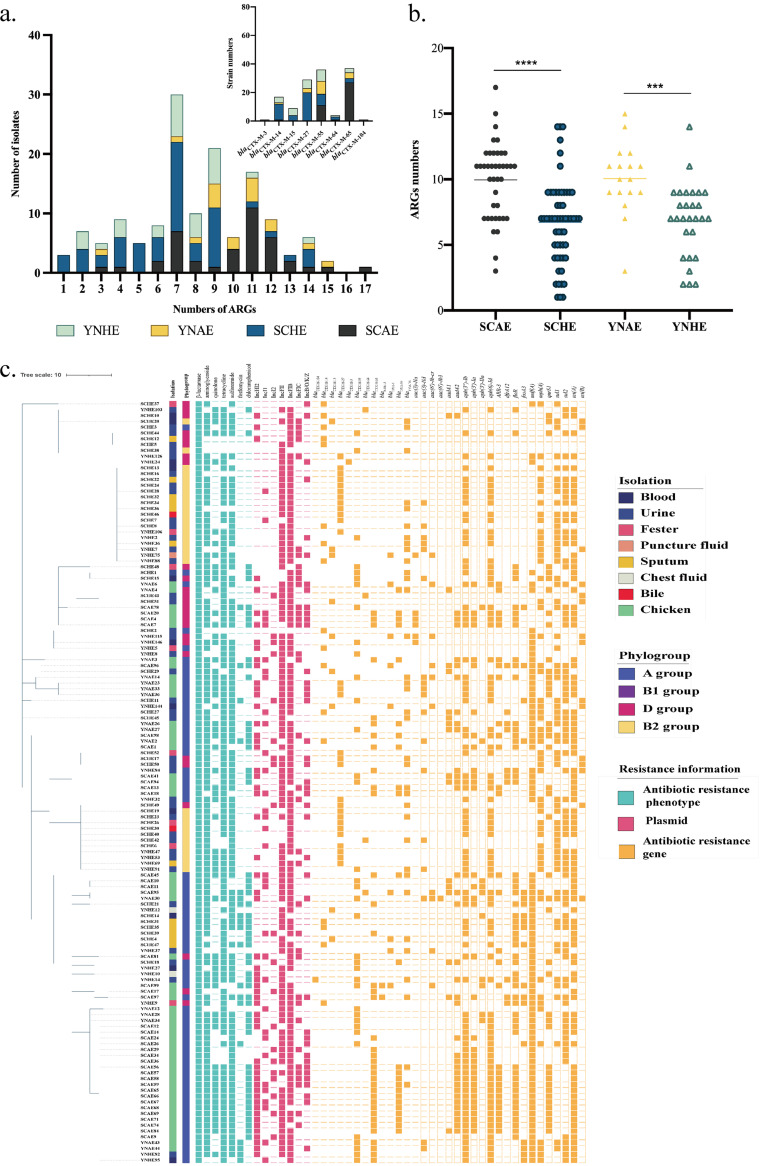

AST and antimicrobial resistance gene analysis.

Ceftriaxone (CRO), gentamicin (GEN), levofloxacin (LVX), tetracycline (TET), sulfamethoxazole (SXT), fosfomycin (FOS), and florfenicol (FFC) were used to perform an antimicrobial sensitivity test (AST) based on CLSI experimental guidance. Consequently, 92.37% (12/131) of CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates showed multiple drug resistance (Fig. 4; Table S5). Besides the resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, the resistance rates against tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, chloramphenicol, and fosfomycin were 86.26% (113/131), 84.73% (111/113), 80.92% (106/131), 41.98% (55/131), and 14.5% (19/131), respectively. To understand the antimicrobial resistance characteristics of these strains, 131 strains of CTX-ESBL-E. coli were used for whole-genome sequencing. The antibiotic resistance genes and plasmids in the genome sequence were searched using ResFinder and PlasmidFinder on the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) website, and we analyzed 33 antibiotic resistance genes (including 12 β-lactam resistance genes, 10 aminoglycoside resistance genes, 1 rifampicin resistance gene, 1 diaminopyrimidine resistance gene, 1 chloramphenicol resistance gene, 1 fosfomycin resistance gene, 3 tetracycline resistance genes, 1 macrolide resistance gene, 1 quinolone resistance gene, and 2 sulfonamide resistance genes) and 7 plasmids (Fig. 4c). Further, 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from different sources were classified and assessed for the number of various drug resistance genes (Fig. 4a): 30 strains had 7 drug resistance genes (including 8 chicken farm isolates and 22 clinical isolates) and 21 strains had 9 drug resistance genes (including 5 chicken farm isolates and 16 clinical isolates).

FIG 4.

Antimicrobial sensitivity test, antimicrobial resistance genes, and plasmid replicon analysis of CTX-ESBL-E. coli. (a) Numbers of various drug resistance genes carried by CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from different regions and sources. The histogram in the upper right corner indicates the number of strains carrying different blaCTX-M genes. ARG, antimicrobial resistance gene. (b) Comparative analysis of the number of drug resistance genes carried by CTX-ESBL-E. coli from different regions and sources. ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. (c) Antibiotic resistance phenotypes, antibiotic resistance genes, and plasmid replicon analysis of the CTX-ESBL-E. coli. The evolutionary tree was constructed using GrapeTree of the EnteroBase site based on the STs and visualized using iTOL v.6.

The plasmid is an important mobile genetic element, housing the majority of the drug resistance genes encoding ESBL. The common replicons include IncF, IncI, IncN, IncHI1, and IncHI2 (6). Most strains in this study carried IncFII and IncFIb plasmids, implying that the drug resistance genes carried by these strains have the potential for horizontal transfer. Moreover, we calculated the blaCTX-M subtypes carried in 194 strains and eventually discovered 12 blaCTX-M subtypes. The predominant subtypes include blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-27, blaCTX-M-55, and blaCTX-M-65. A total of 37 E. coli strains had blaCTX-M-65, whereas 36 E. coli strains carried blaCTX-M-55. The clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates primarily carried blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-27, and blaCTX-M-55, whereas the chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates mainly carried blaCTX-M-55 and blaCTX-M-65. This shows the different prevalent subtypes of CTX-ESBL-E. coli from the two sources. Also, some strains carried two subtypes of blaCTX-M in their genome sequences. A total of 7 strains carrying two subtypes of blaCTX-M were identified, including Sichuan Province chicken farm-derived isolate SCAE99 (blaCTX-M-65, blaCTX-M-55) belonging to ST2582, Yunnan Province farm-derived isolate YNAE14 (blaCTX-M-65, blaCTX-M-14) belonging to ST202, YNAE43 and YNAE44 (blaCTX-M-65, blaCTX-M-55) belonging to ST155, Yunnan clinical isolates YNHE82 and YNHE95 (blaCTX-M-65, blaCTX-M-55) belonging to ST155, and YNHE14 (blaCTX-M-104, blaCTX-M-55) belonging to ST224. These findings show that β-lactam-resistant ST155 E. coli is extensively distributed and easily carries the blaCTX-M gene, which is conducive to horizontal gene transfer. Subsequently, we analyzed the number of drug resistance genes in strains from different sources. We found that chicken farm-derived isolates contained significantly more drug resistance genes than clinical isolates in two provinces (Fig. 4b). The above results confirm that chicken farm-derived E. coli is an important drug resistance gene repository. Therefore, measures should be taken to promptly and effectively regulate the severe situation of bacterial drug resistance in chicken farms.

Analysis of virulence-associated genes.

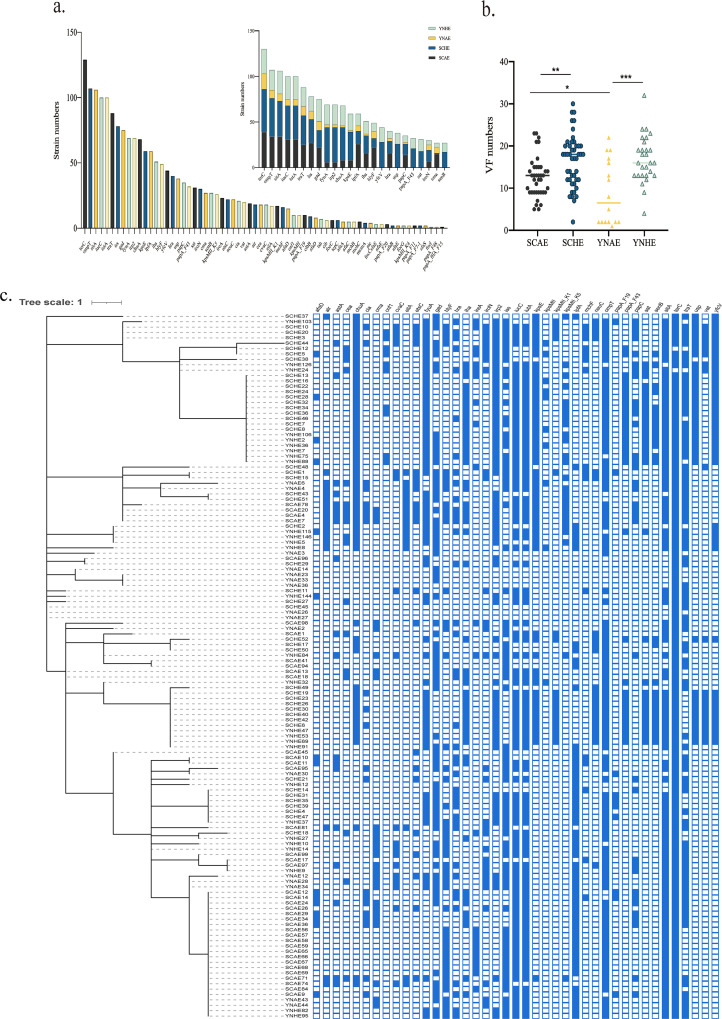

The virulence factors were analyzed to understand the genomic characteristics of 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains (Fig. 5 and Table S6). A total of 66 virulence factors (Fig. 5a) were identified in 131 E. coli strains using VirulenceFinder on the CGE website. terC, an anti-tellurium ion protein-coding gene, had the highest detection rate, followed by outer membrane protein T (OmpT) and sitA (Fig. 5a), involved in ion transport. A single strain contains up to 33 virulence factors (YNHE24), and the minimum number of virulence factors carried by CTX-ESBL-E. coli is 1. We noted differences in virulence factors between chicken farm isolates and clinical isolates, including fyuA, irp2, chuA, kpsE, yfcV, and usp. These virulence genes were significantly and selectively distributed in clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates (Fig. S1, P < 0.0001). Based on an analysis of 24 virulence factors with the highest detection rate in E. coli from different sources, certain differences were observed in the distribution of different virulence factors in the four groups of E. coli. The number of virulence factors of CTX-ESBL-E. coli in each group was analyzed and counted to explore this difference (Fig. 5b). The findings indicate that both clinical isolates from Sichuan Province and those from Yunnan Province contain equivalent virulence factors, which are significantly higher in number than those in chicken farm isolates from Sichuan Province and Yunnan Province. The above results suggest that clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli could have stronger pathogenicity than chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli.

FIG 5.

Analysis of virulence-associated genes. (a) Number of virulence-associated genes in CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from various sources. The histogram in the upper right corner indicates the number of the 24 virulence factors with the highest detection rate carried by the CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from different sources. (b) Comparative analysis of the number of virulence-associated genes carried by CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from different sources; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. (c) Virulence-associated gene distribution in the CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates, the evolutionary tree was constructed using GrapeTree of the EnteroBase site based on the STs and visualized using iTOL v.6.

Comparison of the relationship between antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence factors, and STs.

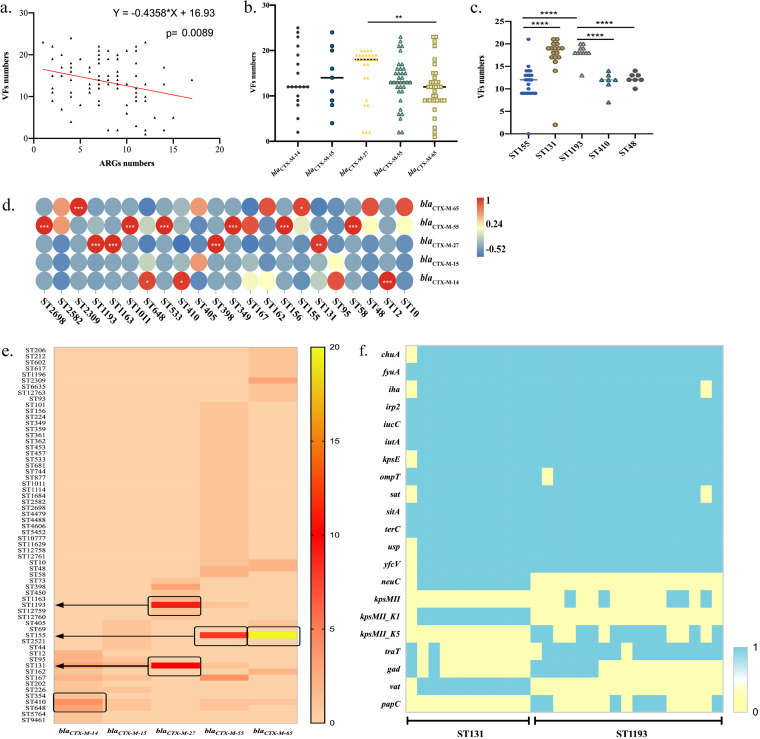

The distribution of different blaCTX-M genes in E. coli with different sources was analyzed, and consequently, we found more blaCTX-M subtypes in the clinical E. coli isolates than in chicken farm isolates. The clinical E. coli isolates had blaCTX-M-3, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-27, blaCTX-M-55, blaCTX-M-64, blaCTX-M-65, and blaCTX-M-104, among which blaCTX-M-55 and blaCTX-M-27 were dominant. The chicken farm isolates contained blaCTX-M-55, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-27, and blaCTX-M-65, among which blaCTX-M-55 and blaCTX-M-65 were dominant. Nonlinear regression analysis was used to analyze the relationship between the numbers of drug resistance genes and virulence genes in CTX-ESBL-E. coli. Consequently, we found a negative correlation between antibiotic resistance and virulence genes (Fig. 6a). Subsequently, we counted the number of virulence factors in CTX-ESBL-E. coli containing blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-27, blaCTX-M-55, and blaCTX-M-65 genes. The results showed that E. coli carrying blaCTX-M-27 had the largest number of average virulence factors, which was significantly higher than that of E. coli carrying blaCTX-M-65 (Fig. 6b, P = 0.0016).

FIG 6.

Comparison of the relationships between antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence genes, and STs. (a) Correlation between antibiotic resistance genes and virulence genes. VF, virulence factor. (b) Number of virulence factors in CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates containing various blaCTX-M genes. (c) Number of virulence factors in different STs of E. coli. (d and e) Correlation between blaCTX-M genes and STs. *, 0.01 < P < 0.05; **, 0.001 < P < 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. (f) Virulence factors in ST131 and ST1193 E. coli.

We analyzed the number of virulence factors in ST131, ST155, ST410, ST48, and ST1193 E. coli. According to statistical analyses, the number of virulence factors in different STs varied significantly. Among them, the virulence factors carried by ST131 and ST1193 E. coli were significantly higher in number than those carried by ST410, ST155, and ST48 (Fig. 6c, P < 0.0001), further explaining the strong pathogenicity of ST131 and ST1193 as global epidemic high-risk clones. Integrated with blaCTX-M subtype analysis, blaCTX-M-27 was primarily distributed in ST131, ST1193, ST1163, and ST398. Unlike the global epidemic ST131, which was prone to carry blaCTX-M-15 (32), we found that ST131 is prone to carry blaCTX-M-27. blaCTX-M-14 is primarily distributed in ST12, ST410, and ST648 and has a stronger correlation with ST12. Further, blaCTX-M-65 and blaCTX-M-55 were distributed in various STs (Fig. 6d and e). ST155 and ST410 E. coli strains were divided into the A group in phylogrouping, whereas ST1193 and ST131 were divided into the B2 group, which is more pathogenic. Therefore, significant attention should be paid to the epidemic characteristics of these high-risk pathogenic E. coli clones.

Later, we analyzed the virulence factors carried by ST131 and ST1193 E. coli (Fig. 6f). The results showed that the ST131 and ST1193 E. coli strains were likely to carry specific virulence factors, including chuA, fyuA, iha, irp2, iucC, iutA, kpsE, OmpT, sat, and usp (Fig. 6f). kpsMII_K1 and vat were significantly distributed in ST131 E. coli, whereas kpsMII_K1 and traT were more likely to be distributed in ST1193 E. coli. ST1193 belongs to the ST14 clonal complex (STc14) within E. coli phylogroup B2, which causes human parenteral diseases (33, 34). However, the effects of kpsMII_K1 and traT on the pathogenicity of ST1193 E. coli remain unclear. Studies indicate that the strong adaptability of ST131 E. coli could be related to multiple factors (35). These virulence genes are conducive to improving the versatility and competitiveness of E. coli and the capacity to infect humans. Virulence genes are often located on plasmids; therefore, they are more likely to spread to other E. coli strains with the transferable plasmids, causing changes in the pathogenicity of E. coli. Nonetheless, the precise role of these pathogenic genes remains unexplained.

DISCUSSION

Excessive use of antibiotics promotes bacterial drug resistance. This work investigated the genomic characteristics of ESBL-E. coli isolated from chicken farms and human medical clinics of Sichuan Province and Yunnan Province, China. The isolation rate of ESBL-E. coli in Sichuan Province was 48% (48/100), whereas that in Yunnan Province was 45.35% (156/344); both were slightly lower than the 58.8% rate in Shanghai (36). We found that the prevalence rate of chicken farm-derived ESBL-E. coli was 34.34% (204/594), which was significantly lower than the 78.6% reported by Liu et al. (37). The above results indicate that the ESBL-E. coli prevalence varied by sources and area from the overall prevalence. Therefore, it is necessary to further analyze the genomic characteristics of ESBL-E. coli in different regions to initiate a reasonable medication strategy. MLST evolution and SNP analyses were performed to analyze the genetic correlation between human and chicken farm CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates. In MLST analysis, the prevalent STs among 194 strains of CTX-ESBL-E. coli included ST155 and ST131. Among them, the main STs in human CTX-ESBL-E. coli were ST131 and ST1193, which is in line with other reports (38, 39). ST131 and ST1193 are the prevalent STs of E. coli with global high-risk occurrence (34, 40). Of note, ST155 is the primary ST of chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli. The human- and chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates have significantly different STs, as reported by previous studies (41). Additional analyses showed that ST162, ST156, ST10, ST155, ST167, and ST226 are major STs in isolates from humans and chicken farms. This indicates that these STs easily spread between humans and animals. The outcomes of SNP analysis are similar to those of MLST analysis. CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from chicken farms and human sources have generally conserved genetic features. However, strains from humans and chicken farms in the same region have a high genetic similarity. The above findings indicate the possibility of cross-transmission of drug-resistant bacteria between poultry and humans in the same region.

Analysis of the resistance genes carried by CTX-ESBL-E. coli revealed that the resistance genes carried by chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli were significantly higher in number than those in their clinical counterparts. This demonstrates that avian E. coli is a vital repository of drug resistance genes. Antibiotic use and antimicrobial-resistant bacterium monitoring in the livestock and poultry breeding industries should be comprehensively managed. These bacteria may be a repository of drug resistance genes and transfer these genes to other pathogens, resulting in clinical treatment failure. Therefore, the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance in chicken farm-derived E. coli presents an urgent demand for the prudent use of antibiotics. Additionally, the isolation rate of blaCTX-M in ESBL-E. coli was 82.62%, indicating that the blaCTX-M gene is responsible for β-lactam resistance. We analyzed the blaCTX-M subtypes carried by CTX-ESBL-E. coli and discovered that the clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates primarily carried blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-27, and blaCTX-M-55, whereas chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates mainly carried blaCTX-M-55 and blaCTX-M-65, which was consistent with previous reports (42). Notably, the prevalent blaCTX-M gene subtypes of CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates from different sources were different, although blaCTX-M-55 is a major global epidemic subtype (43). As the conjugative transfer plasmids, IncFII and IncFIb plasmids mediate the horizontal transfer of blaCTX-M (44–47). Therefore, the mechanism of resistance gene transfer mediated by plasmids should be further analyzed to manage the spread of drug resistance. In the pathogenicity analysis of CTX-ESBL-E. coli from different sources, we analyzed the phylogroups and virulence factors of 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains. In line with previous studies, the majority of chicken farm-derived E. coli strains belong to the A group, whereas only a few CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains belong to the D group (48, 49). In contrast, above half of human-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains are pathogenic E. coli, primarily belonging to the B2 group. This work suggests that multidrug-resistant E. coli strains of phylogroups A and D have transmission potential between chicken farms and humans, and such subpopulations should be of public health concern. Similar to phylogroup results, clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains appear to carry more virulence factors. Six virulence factors, fyuA, irp2, chuA, kpsE, yfcV, and usp, were significantly distributed in clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli compared to chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, P < 0.0001). Several of the above virulence factors are involved in ferric ion uptake and transport, which are typical pathogen characteristics. Therefore, we thought that clinical CTX-ESBL-E. coli could evolve toward higher levels of virulence. Regarding the relationships between drug resistance genes, virulence factors, and STs, E. coli strains carrying blaCTX-M-27 harbor more virulence factors because blaCTX-M-27 is extensively distributed in ST131 and ST1193 E. coli. This result is distinct from the ST131 global outbreak, which has blaCTX-M-15 (50). ST131 and ST1193 are high-risk E. coli clones with more virulence factors than other STs and usually trigger severe infections. Although we did not identify chicken farm-derived ST131 E. coli, ST131 and ST1193 E. coli clones can be transmitted between humans and animals (51). Therefore, prevention and control should focus on ST131 and ST1193 E. coli with blaCTX-M-27.

The transmission relationship between human- and animal-derived ESBL-E. coli isolates is unclear. Researchers suggest that there is no apparent relationship between human- and animal-derived ESBL-E. coli strains (52). However, there is an indistinguishable association between human- and animal-derived ESBL-E. coli strains, where plasmids are the key vectors driving the horizontal transmission of ESBL genes (53). ESBL-E. coli is an important contaminant in retail chicken meat (54). In this work, a small number of chicken farm-derived E. coli and clinical E. coli isolates were clonally related, suggesting a potential relationship between ESBL-E. coli isolates derived from animals and those from humans. Although human- and avian-origin ESBL-E. coli strains are less clonally related, avian-origin ESBL-E. coli should be comprehensively monitored as an important repository of drug resistance genes (55). In contrast with the phylogenetic relationship between clinical and avian-origin E. coli strains, additional clonally close isolates were isolated within hospitals, indicating that the present spread of clinical resistant bacteria is still dominated by nosocomial transmission. Also, several studies indicate that avian-pathogenic bacteria can be transmitted to humans via the food chain or human-animal contact (43, 56). Although China banned the use of colistin as an animal growth-promoting agent in the livestock farming industry in 2017, antibiotic use for preventive or therapeutic purposes in the broad context of large-scale farming is inevitable. Therefore, strategies for preventing, and measuring the traceability of, drug-resistant bacteria in the farming industry should be implemented. Tracing and exploring the potential animal-human transmission chain provide additional comprehensive insights into understanding resistance in chicken farms. This is critical for developing strategies to minimize antibiotic resistance in chicken farms in different regions.

However, this study has compelling limitations. First, the hospital-derived E. coli strains were isolated from patients and exhibited significant pathogenicity. However, the chicken farm-derived E. coli counterparts were isolated from healthy laying hens and mostly belonged to commensals, causing a large difference between the E. coli strains from the two sources. Therefore, to compensate for possible errors, we also supplemented the genome information of E. coli from the two provinces in the EnteroBase database in the analysis of drug resistance genes and virulence genes. To better understand the transmission relationship of CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates between poultry and humans, sample sources should be expanded to cover healthy individuals, since chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates are likely to cause asymptomatic infection in patients. Therefore, follow-up studies should expand the scope of sample collection for a more comprehensive analysis.

In conclusion, we used whole-genome sequencing to analyze the epidemic characteristics of clinical and avian-origin CTX-ESBL-E. coli. Moreover, we comprehensively analyzed the epidemic characteristics, transmission patterns, and risk factors of CTX-ESBL-E. coli from the genomic level. Our findings indicate that CTX-ESBL-E. coli has some differences in isolation rates among different regions. Besides, blaCTX-M-55 is the dominant β-lactam resistance gene of CTX-ESBL-E. coli of both human and poultry origins. Despite the limited link between clinical and chicken farm-derived CTX-ESBL-E. coli isolates, we found multiple identical STs distributed between chicken farm- and human-derived E. coli isolates and even the same clone in part of the chicken farm- and human-derived E. coli isolates. Therefore, significant research attention should be paid to the clinical and avian-origin CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains, as well as to β-lactam antibiotic use in poultry farms. To improve our understanding of the hypervirulent ESBL-E. coli, research should focus on ST131 and ST1193 E. coli carrying blaCTX-M-27.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and identification of E. coli and AST.

Chicken anal swabs from 15 chicken farms in Sichuan Province and Yunnan Province were collected between January and September 2021. First, the samples were placed in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium and incubated for preliminary enrichment bacteria. Subsequently, the overnight culture broth was streaked onto eosin-methylene blue (EMB) agar medium and cultured overnight at 37°C. Single colonies with similar morphological characteristics (metal luster colonies) were picked and confirmed as E. coli by colony PCR using 16S rRNA gene primers (F, GAAGCTTGCTTCTTTGCT; R, GAGCCCGGGGATTTCACAT). Meanwhile, the E. coli strains were collected from two grade III hospitals located in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, respectively.

The ESBL production test and antimicrobial sensitivity test (AST) were performed in line with the CLSI guidelines (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, version M100-Ed31). Ceftazidime, cefotaxime (30 μg), and their compound reagents with clavulanic acid (30 μg/10 μg) were used for the identification of ESBL production in E. coli. The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion susceptibility test was conducted based on CLSI guidelines, and ceftriaxone (CRO, 30 μg), gentamicin (GEN, 10 μg), levofloxacin (LVX, 5 μg), tetracycline (TET, 30 μg), sulfamethoxazole (SXT, 23.75 μg), fosfomycin (FOS, 200 μg), and florfenicol (FFC, 30 μg) were used as the test antibiotics. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoint (v 12.0) was used for interpretation if the CLSI breakpoint was unavailable.

Analysis of phylogenetic group.

Phylogrouping is a convenient, simple, and rapid technique that differentiates phylogenetic groups (pathogenic, opportunistic pathogenic, or commensal) of E. coli. Based on the work of Clermont et al. (57), three gene segments, chuA, yjaA, and TSPE4.C2, were amplified by PCR and combined to form 4 classes of phylogroups. The judgment basis of the results was as follows: when the three fragments were not successfully amplified or only the yjaA gene was successfully amplified, they were classified as group A; when only the TSPE4.C2 fragment was successfully amplified, it was classified as group B1; when only chuA fragments were successfully amplified or both chuA and TSPE4.C2 fragments were successfully amplified, they were classified as group D; when chuA and yjaA fragments were successfully amplified or all three fragments were successfully amplified, they were classified as group B2. In the four phylogenetic groups, the commensal strains belonged to the A group, the weak-pathogenicity strains belonged to the B1 group, the somewhat pathogenic strains belonged to the D group, and the virulent strains belonged to the B2 group.

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis.

The genomic DNA (gDNA) of the 131 CTX-ESBL-E. coli strains was extracted using the TIANamp bacterial DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech [Beijing] Co., Ltd., China) following the manufacturer’s recommendation. This gDNA was subjected to short-read whole-genome sequencing (WGS). The WGS results were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform (150-bp paired-end reads with approximately 200-fold average coverage). The clean data were assembled into draft genomes using SPAdes_3.13.0 software. For whole-genome sequence analysis, the phylogenetic tree based on SNPs was constructed using CGE CSI Phylogeny 1.4 with default parameters (58), which were observed using the Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL v6, https://itol.embl.de/) (58). The genome sequence of E. coli C600 (EC600, GenBank accession no. CP031214.1) was used as a reference. A threshold of 5 SNPs among isolates was considered to show them to be clonally related and likely to have an epidemiological link (59). Sequence types were identified through the ST(s) Find website at EnteroBase (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/species/ecoli/search_strains?query=st_search) (60). A minimal spanning tree was constructed using GrapeTree, version 1.5.061 (https://enterobase.readthedocs.io/en/latest/grapetree/grapetree-about.html) (61), an interactive tree visualization program in EnteroBase. Antimicrobial resistance genes, plasmids, and serotypes were identified using ResFinder 4.1, PlasmidFinder 2.1, and SerotypeFinder 2.0 on the CGE website (62–64).

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistical analyses on percentages with standard deviation and prevalence were performed using functions provided in Excel 2021 (Microsoft Software). All statistical analyses (unpaired t test, nonlinear regression analysis) were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyze the relationship between STs and antimicrobial resistance genes with values being shown as follows: P > 0.05, no label; 0.01 < P < 0.05, labeled *; 0.001 < P < 0.01, labeled **; P ≤ 0.001, labeled ***; and P ≤ 0.0001, labeled ****.

Data availability.

All 131 E. coli genomes sequenced in this study have been uploaded to the NCBI WGS database associated with BioProject under accession no. PRJNA817453 (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). Also, the draft genomes of 63 E. coli strains (distributed in poultry and human sources from Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, respectively) were downloaded from EnteroBase (Table S7) and included in the phylogenetic analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We warmly thank Limin Chen at the Institute of Blood Transfusion, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Ying Xu at the Clinical Medical College and the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College, and supervising technician Jiawei Ding in Yan’an Hospital Affiliated to Kunming Medical University for their help with offering clinical strains. We also thank the cooperative chicken farm workers for chicken anal swab sampling.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U21A20257 and grant no. 31830098), the National System for Layer Production Technology (grant no. CARS-40-K14), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. SCU2021D006 and grant no. 2020SCUNL206), and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (grant no. 2020NZZJ001).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Hongning Wang, Email: whongning@163.com.

Cezar M. Khursigara, University of Guelph

REFERENCES

- 1.Peng Z, Hu Z, Li Z, Zhang X, Jia C, Li T, Dai M, Tan C, Xu Z, Wu B, Chen H, Wang X. 2022. Antimicrobial resistance and population genomics of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in pig farms in mainland China. Nat Commun 13:1116. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28750-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. 2022. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitout JD, Laupland KB. 2008. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis 8:159–166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benlabidi S, Raddaoui A, Achour W, Hassen B, Torres C, Abbassi MS, Ghrairi T. 2021. Genetic characterization of ESBL/pAmpC-producing Escherichia coli isolated from forest, urban park and cereal culture soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 97:fiab146. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiab146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossolini GM, D’Andrea MM, Mugnaioli C. 2008. The spread of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Infect 14(Suppl 1):33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poirel L, Madec JY, Lupo A, Schink AK, Kieffer N, Nordmann P, Schwarz S. 2018. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr 6. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0026-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Kumar Mishra S, Wang T, Xu Z, Zhao X, Wang Y, Yin H, Fan X, Zeng B, Yang M, Yang D, Ni Q, Li Y, Zhang M, Zhu Q, Chen F, Li D. 2020. AFB1 induced transcriptional regulation related to apoptosis and lipid metabolism in liver of chicken. Toxins 12:290. doi: 10.3390/toxins12050290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muaz K, Riaz M, Akhtar S, Park S, Ismail A. 2018. Antibiotic residues in chicken meat: global prevalence, threats, and decontamination strategies: a review. J Food Prot 81:619–627. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-17-086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2022. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2019-2020. EFSA J 20:e07209. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Robinson TP, Teillant A, Laxminarayan R. 2015. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiseo K, Huber L, Gilbert M, Robinson TP, Van Boeckel TP. 2020. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals from 2017 to 2030. Antibiotics (Basel) 9:918. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9120918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schar D, Klein EY, Laxminarayan R, Gilbert M, Van Boeckel TP. 2020. Global trends in antimicrobial use in aquaculture. Sci Rep 10:21878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schar D, Zhao C, Wang Y, Larsson DGJ, Gilbert M, Van Boeckel TP. 2021. Twenty-year trends in antimicrobial resistance from aquaculture and fisheries in Asia. Nat Commun 12:5384. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25655-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rawat N, Anjali Jamwal R, Devi PP, Yadav K, Kumar N, Rajagopal R. 2022. Detection of unprecedented level of antibiotic resistance and identification of antibiotic resistance factors, including QRDR mutations in Escherichia coli isolated from commercial chickens from North India. J Appl Microbiol 132:268–278. doi: 10.1111/jam.15209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandal AK, Talukder S, Hasan MM, Tasmim ST, Parvin MS, Ali MY, Islam MT. 2022. Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli in broiler chickens, farmworkers, and farm sewage in Bangladesh. Vet Med Sci 8:187–199. doi: 10.1002/vms3.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim DG, Kim K, Bae SH, Jung HR, Kang HJ, Lee YJ, Seo KW, Lee YJ. 2022. Comparison of antimicrobial resistance and molecular characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from layer breeder farms in Korea. Poult Sci 101:101571. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang M, Jiang M, Wang Z, Chen R, Zhuge X, Dai J. 2021. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance in chicken-source phylogroup F Escherichia coli: similar populations and resistance spectrums between E. coli recovered from chicken colibacillosis tissues and retail raw meats in Eastern China. Poult Sci 100:101370. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Laupland KB, Poirel L. 2005. Emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother 56:52–59. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day MJ, Rodriguez I, van Essen-Zandbergen A, Dierikx C, Kadlec K, Schink AK, Wu G, Chattaway MA, DoNascimento V, Wain J, Helmuth R, Guerra B, Schwarz S, Threlfall J, Woodward MJ, Coldham N, Mevius D, Woodford N. 2016. Diversity of STs, plasmids and ESBL genes among Escherichia coli from humans, animals and food in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1178–1182. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaheen BW, Nayak R, Foley SL, Kweon O, Deck J, Park M, Rafii F, Boothe DM. 2011. Molecular characterization of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in clinical Escherichia coli isolates from companion animals in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:5666–5675. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00656-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmiedel J, Falgenhauer L, Domann E, Bauerfeind R, Prenger-Berninghoff E, Imirzalioglu C, Chakraborty T. 2014. Multiresistant extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from humans, companion animals and horses in central Hesse, Germany. BMC Microbiol 14:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewers C, Bethe A, Semmler T, Guenther S, Wieler LH. 2012. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from livestock and companion animals, and their putative impact on public health: a global perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:646–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso MP, Canica MM, Park YJ, Lavigne JP, Pitout J, Johnson JR. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:273–281. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau SH, Kaufmann ME, Livermore DM, Woodford N, Willshaw GA, Cheasty T, Stamper K, Reddy S, Cheesbrough J, Bolton FJ, Fox AJ, Upton M. 2008. UK epidemic Escherichia coli strains A-E, with CTX-M-15 beta-lactamase, all belong to the international O25:H4-ST131 clone. J Antimicrob Chemother 62:1241–1244. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathers AJ, Peirano G, Pitout JD. 2015. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:565–591. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00116-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song J, Oh SS, Kim J, Park S, Shin J. 2020. Clinically relevant extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from food animals in South Korea. Front Microbiol 11:604. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vimont S, Boyd A, Bleibtreu A, Bens M, Goujon JM, Garry L, Clermont O, Denamur E, Arlet G, Vandewalle A. 2012. The CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli clone O25b: H4-ST131 has high intestine colonization and urinary tract infection abilities. PLoS One 7:e46547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Day MJ, Hopkins KL, Wareham DW, Toleman MA, Elviss N, Randall L, Teale C, Cleary P, Wiuff C, Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Woodford N, Livermore DM. 2019. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in human-derived and foodchain-derived samples from England, Wales, and Scotland: an epidemiological surveillance and typing study. Lancet Infect Dis 19:1325–1335. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Athanasakopoulou Z, Tsilipounidaki K, Sofia M, Chatzopoulos DC, Giannakopoulos A, Karakousis I, Giannakis V, Spyrou V, Touloudi A, Satra M, Galamatis D, Diamantopoulos V, Mpellou S, Petinaki E, Billinis C. 2021. Poultry and wild birds as a reservoir of CMY-2 producing Escherichia coli: the first large-scale study in Greece. Antibiotics 10:235. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martak D, Guther J, Verschuuren TD, Valot B, Conzelmann N, Bunk S, Riccio ME, Salamanca E, Meunier A, Henriot CP, Brossier CP, Bertrand X, Cooper BS, Harbarth S, Tacconelli E, Fluit AC, Rodriguez-Bano J, Kluytmans J, Peter S, Hocquet D, MODERN WP3 study group . 2022. Populations of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are different in human-polluted environment and food items: a multicentre European study. Clin Microbiol Infect 28:447.e7–447.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ewers C, Li G, Wilking H, Kiessling S, Alt K, Antáo EM, Laturnus C, Diehl I, Glodde S, Homeier T, Böhnke U, Steinrück H, Philipp HC, Wieler LH. 2007. Avian pathogenic, uropathogenic, and newborn meningitis-causing Escherichia coli: how closely related are they? Int J Med Microbiol 297:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Negeri AA, Mamo H, Gurung JM, Firoj Mahmud AKM, Fallman M, Seyoum ET, Feleke Desta A, Francis MS. 2021. Antimicrobial resistance profiling and molecular epidemiological analysis of extended spectrum beta-lactamases produced by extraintestinal invasive Escherichia coli isolates from Ethiopia: the presence of international high-risk clones ST131 and ST410 revealed. Front Microbiol 12:706846. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.706846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tchesnokova V, Radey M, Chattopadhyay S, Larson L, Weaver JL, Kisiela D, Sokurenko EV. 2019. Pandemic fluoroquinolone resistant Escherichia coli clone ST1193 emerged via simultaneous homologous recombinations in 11 gene loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:14740–14748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson TJ, Elnekave E, Miller EA, Munoz-Aguayo J, Flores FC, Johnston B, Nielson DW, Logue CM, Johnson JR. 2019. Phylogenomic analysis of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli sequence type 1193, an emerging multidrug-resistant clonal group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e01913-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01913-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobrindt U. 2005. (Patho-)genomics of Escherichia coli. Int J Med Microbiol 295:357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao S, Tang C, Zeng Q, Xue Y, Chen Q, Chen E, Han L. 2021. Antimicrobial resistance and molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli from bloodstream infection in Shanghai, China, 2016–2019. Front Med (Lausanne) 8:803837. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.803837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z, Wang K, Zhang Y, Xia L, Zhao L, Guo C, Liu X, Qin L, Hao Z. 2021. High prevalence and diversity characteristics of blaNDM, mcr, and blaESBLs harboring multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli from chicken, pig, and cattle in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11:755545. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.755545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahazu S, Sato W, Ayibieke A, Prah I, Hayashi T, Suzuki T, Iwanaga S, Ablordey A, Saito R. 2022. Insights and genetic features of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli isolates from two hospitals in Ghana. Sci Rep 12:1843. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05869-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toth K, Toth A, Kamotsay K, Nemeth V, Szabo D. 2022. Population snapshot of the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli invasive strains isolated from a Hungarian hospital. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 21:3. doi: 10.1186/s12941-022-00493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumura Y, Pitout JD, Gomi R, Matsuda T, Noguchi T, Yamamoto M, Peirano G, DeVinney R, Bradford PA, Motyl MR, Tanaka M, Nagao M, Takakura S, Ichiyama S. 2016. Global Escherichia coli sequence type 131 clade with blaCTX-M-27 gene. Emerg Infect Dis 22:1900–1907. doi: 10.3201/eid2211.160519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen MN, Hoang HTT, Xavier BB, Lammens C, Le HT, Hoang NTB, Nguyen ST, Pham NT, Goossens H, Dang AD, Malhotra-Kumar S. 2021. Prospective One Health genetic surveillance in Vietnam identifies distinct blaCTX-M-harbouring Escherichia coli in food-chain and human-derived samples. Clin Microbiol Infect 27:1515.e1–1515.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo S, Aung KT, Leekitcharoenphon P, Tay MYF, Seow KLG, Zhong Y, Ng LC, Aarestrup FM, Schlundt J. 2021. Prevalence and genomic analysis of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in retail raw meats in Singapore. J Antimicrob Chemother 76:601–605. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salinas L, Loayza F, Cardenas P, Saraiva C, Johnson TJ, Amato H, Graham JP, Trueba G. 2021. Environmental spread of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli and ESBL genes among children and domestic animals in Ecuador. Environ Health Perspect 129:27007. doi: 10.1289/EHP7729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Peng S, Xu J, Li Y, Pu L, Han X, Feng Y. 2022. Genetic context diversity of plasmid-borne blaCTX-M-55 in Escherichia coli isolated from waterfowl. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 28:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2022.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocha-Gracia RDC, Lozano-Zarain P, Gutierrez Cazarez Z, Alonso CA, Brambila E, Torres C, Cortes-Cortes G. 2022. IncFIB plasmids carrying the resistance gene blaCTX-M-15 in ESBL-producing Escherichia coli clones from pediatric patients. J Infect Dev Ctries 16:500–506. doi: 10.3855/jidc.15080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bird MT, Greig DR, Nair S, Jenkins C, Godbole G, Gharbia SE. 2022. Use of nanopore sequencing to characterise the genomic architecture of mobile genetic elements encoding blaCTX-M-15 in Escherichia coli causing travellers’ diarrhoea. Front Microbiol 13:862234. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.862234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang J, Zhu J, Gong D, Wu L, Zhu Y, Hu L. 2022. Whole genome sequence of EC16, a blaNDM-5-, blaCTX-M-55-, and fosA3-coproducing Escherichia coli ST167 clinical isolate from China. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 29:296–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2022.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yun J, Mao L, Li J, Hao F, Yang L, Zhang W, Sun M, Liu M, Wang S, Li W. 2022. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial resistance profile of pathogenic Escherichia coli from goats with respiratory disease in eastern China. Microb Pathog 166:105501. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Halaji M, Fayyazi A, Rajabnia M, Zare D, Pournajaf A, Ranjbar R. 2022. Phylogenetic group distribution of uropathogenic Escherichia coli and related antimicrobial resistance pattern: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:790184. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.790184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurittu P, Khakipoor B, Jalava J, Karhukorpi J, Heikinheimo A. 2021. Whole-genome sequencing of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from human infections in Finland revealed isolates belonging to internationally successful ST131-C1-M27 subclade but distinct from non-human sources. Front Microbiol 12:789280. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.789280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kidsley AK, White RT, Beatson SA, Saputra S, Schembri MA, Gordon D, Johnson JR, O’Dea M, Mollinger JL, Abraham S, Trott DJ. 2020. Companion animals are spillover hosts of the multidrug-resistant human extraintestinal Escherichia coli pandemic clones ST131 and ST1193. Front Microbiol 11:1968. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miltgen G, Martak D, Valot B, Kamus L, Garrigos T, Verchere G, Gbaguidi-Haore H, Ben Cimon C, Ramiandrisoa M, Picot S, Lignereux A, Masson G, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Belmonte O, Cardinale E, Hocquet D, Mavingui P, Bertrand X. 2022. One Health compartmental analysis of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli on Reunion Island reveals partitioning between humans and livestock. J Antimicrob Chemother 77:1254–1262. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkac054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leverstein-van Hall MA, Dierikx CM, Cohen Stuart J, Voets GM, van den Munckhof MP, van Essen-Zandbergen A, Platteel T, Fluit AC, van de Sande-Bruinsma N, Scharinga J, Bonten MJM, Mevius DJ, National ESBL surveillance group . 2011. Dutch patients, retail chicken meat and poultry share the same ESBL genes, plasmids and strains. Clin Microbiol Infect 17:873–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Casella T, Nogueira MCL, Saras E, Haenni M, Madec JY. 2017. High prevalence of ESBLs in retail chicken meat despite reduced use of antimicrobials in chicken production, France. Int J Food Microbiol 257:271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rehman MA, Rempel H, Carrillo CD, Ziebell K, Allen K, Manges AR, Topp E, Diarra MS. 2022. Virulence genotype and phenotype of multiple antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from broilers assessed from a “One-Health” perspective. J Food Prot 85:336–354. doi: 10.4315/JFP-21-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adefioye OJ, Weinreich J, Rodiger S, Schierack P, Olowe OA. 2021. Phylogenetic characterization and multilocus sequence typing of extended-spectrum beta lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from food-producing animals, beef, and humans in southwest Nigeria. Microb Drug Resist 27:111–120. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:4555–4558. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaas RS, Leekitcharoenphon P, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. 2014. Solving the problem of comparing whole bacterial genomes across different sequencing platforms. PLoS One 9:e104984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dallman TJ, Byrne L, Ashton PM, Cowley LA, Perry NT, Adak G, Petrovska L, Ellis RJ, Elson R, Underwood A, Green J, Hanage WP, Jenkins C, Grant K, Wain J. 2015. Whole-genome sequencing for national surveillance of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157. Clin Infect Dis 61:305–312. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou Z, Alikhan NF, Mohamed K, Fan Y, Agama Study Group, Achtman M. 2020. The EnteroBase user’s guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res 30:138–152. doi: 10.1101/gr.251678.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou Z, Alikhan NF, Sergeant MJ, Luhmann N, Vaz C, Francisco AP, Carrico JA, Achtman M. 2018. GrapeTree: visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res 28:1395–1404. doi: 10.1101/gr.232397.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Moller Aarestrup F, Hasman H. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joensen KG, Tetzschner AM, Iguchi A, Aarestrup FM, Scheutz F. 2015. Rapid and easy in silico serotyping of Escherichia coli isolates by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol 53:2410–2426. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00008-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bortolaia V, Kaas RS, Ruppe E, Roberts MC, Schwarz S, Cattoir V, Philippon A, Allesoe RL, Rebelo AR, Florensa AF, Fagelhauer L, Chakraborty T, Neumann B, Werner G, Bender JK, Stingl K, Nguyen M, Coppens J, Xavier BB, Malhotra-Kumar S, Westh H, Pinholt M, Anjum MF, Duggett NA, Kempf I, Nykasenoja S, Olkkola S, Wieczorek K, Amaro A, Clemente L, Mossong J, Losch S, Ragimbeau C, Lund O, Aarestrup FM. 2020. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0001.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (14.4KB, xlsx)

Table S2. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0002.xls, XLS file, 0.3 MB (261KB, xls)

Table S3. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0003.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.02 MB (18.1KB, xlsx)

Table S4. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0004.xls, XLS file, 0.03 MB (27.5KB, xls)

Table S5. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0005.xlsx, XLSX file, 2.6 MB (2.6MB, xlsx)

Table S6. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0006.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.02 MB (20.5KB, xlsx)

Table S7. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0007.xls, XLS file, 0.08 MB (82KB, xls)

Fig. S1. Download spectrum.02557-22-s0008.tif, TIF file, 0.4 MB (445.6KB, tif)

Data Availability Statement

All 131 E. coli genomes sequenced in this study have been uploaded to the NCBI WGS database associated with BioProject under accession no. PRJNA817453 (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). Also, the draft genomes of 63 E. coli strains (distributed in poultry and human sources from Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, respectively) were downloaded from EnteroBase (Table S7) and included in the phylogenetic analysis.