Abstract

A new class of push-pull-activated alkynes featuring di- and trifluorinated ynol ethers was synthesized. The difluorinated ynol ether exhibited an optimal balance of stability and reactivity, displaying a substantially improved half-life in the presence of aqueous thiols over the previously reported 1-haloalkyne analogs while reacting just as fast in the hydroamination reaction with N,N-diethylhydroxylamine. The trifluorinated ynol ether reacted significantly faster, exhibiting a second order rate constant of 0.56 M−1s−1 in methanol, but it proved too unstable toward thiols. These fluorinated ynol ethers further demonstrate the importance of the hyperconjugation-rehybridization effect in activating alkynes and demonstrate how substituent effects can both activate and stabilize alkynes for bioorthogonal reactivity.

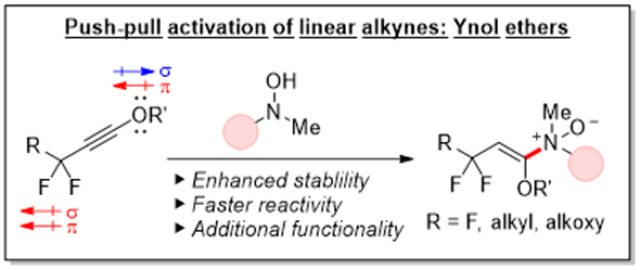

Graphical Abstract

Di- and trifluorinated ynol ethers were synthesized. They illustrate the impact of the hyperconjugation-rehybridization effect in activating alkynes and show how substituent effects can both activate and stabilize alkynes for bioorthogonal reactions.

Bioorthogonal click reactions are ubiquitous across chemistry and biology.1 These simple and selective transformations enable the bioconjugation of small molecules onto a vast array of biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, sugars, and lipids, facilitating the elucidation of complex biological processes both in vitro and in vivo. 1a, 2 The highly efficient and chemoselective transformations have likewise been impactful in areas well removed from the chemical complexities of living organisms, driving applications in polymer and materials science where they have been instrumental in assembling and tailoring the emergent properties of materials.3

The copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction is a foundational member of this class of reactions, and the fast kinetics of this transformation alongside the small footprint of the azide and alkyne components have been keys to its enduring utility.4 Soon after its introduction, efforts to obviate the need for the toxic copper catalyst yielded a strain-promoted variant featuring a strained cyclooctyne,5 which has since undergone electronic and geometric modifications to afford vastly improved ligation rates.6 Success of the strain-promoted azide-alkyne reaction has spawned a panoply of other strain-promoted cycloaddition-based click reactions employing a cyclooctyne7 or an alternative strained system such as a norbornene,8 cyclopropene,9 or trans-cyclooctene10 together with their cognate tetrazine, tetrazole, diazoacetamide, and sydnone reaction partners.

Recently, we described a complementary set of associative and dissociative bioorthogonal transformations centered around an enamine N-oxide motif. We demonstrated that these compounds can be accessed conveniently by hydroamination of activated alkynes using N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines and cleaved rapidly by chemical or hypoxia-induced enzymatic N–O reduction.11 Importantly, these reactions could be used either alone for bioconjugation and prodrug applications or in tandem to achieve the reversible functionalization of biomolecules.12

During our investigations into the bond-forming half of the bioorthogonal reaction pair, we found that unactivated alkynes are poor substrates for the retro-Cope elimination reaction.11 The reaction is sluggish, the product is unstable to the reaction conditions, and the desired anti-Markovnikov enamine N-oxide product could not be obtained in meaningful yields. In contrast, introduction of a single oxygen or comparably electronegative atom at the propargylic position was sufficient in activating the alkyne for hydroamination, affording access to a large collection of structurally diverse enamine N-oxides in high yields and favorable regioselectivities. Still, the reaction was far from bioorthogonal. To render the reaction compatible with biological systems, we investigated the use of strained alkynes, discovering that cyclooctynes react rapidly with hydroxylamines and exhibit a second order rate constant up to 84 M−1s−1 in CD3CN.13

Seeking to miniaturize the alkyne component for biological applications in which probe size matters, we pursued an alternative mode of activation based on a push-pull system, which would roughly preserve the size and profile of the terminal alkyne in the CuAAC reaction.14 In these studies, we discovered that inductively withdrawing alkyne substituents, whether π-donating or accepting, accelerated the hydroamination reaction. We also observed that the directionality of the substituent π-effects was the principal determinant of regioselectivity. Importantly, the combination of a σ-/π-withdrawing substituent at the propargylic position and a σ-withdrawing/π-donating substituent at the terminal position imparted a positive and additive effect on the hydroamination rate while demonstrating a reinforcing sense of regioselectivity. The opposing π-effects of each substituent further acted to neutralize the alkyne toward its reaction with cellular nucleophiles and electrophiles, rendering the reaction bioorthogonal. In this campaign, we specifically investigated 1-haloalkynes, with 1-chloroalkynes displaying an optimal balance between reactivity and stability and undergoing rapid hydroamination by N,N-diethylhydroxylamine with a second order rate constant up to 0.57 M−1s−1 in CD3CN.

In this report, we revisit the bioorthogonal hydroamination reaction of hyperconjugation-rehybridization-activated linear alkynes and extend the scope of the reaction to ynol ethers15 (Figure 1C). We describe a synthetic method to access these novel compounds, evaluate their kinetics, explore their stability profile, and elucidate the nature of their reactivity through DFT calculations.

Figure 1.

Retro-Cope elimination reaction between alkynes and N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines. (A) Rapid bioorthogonal retro-Cope elimination reaction between cyclooctynes and N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines. (B) Bioorthogonal hydroamination reaction of minimalistic push-pull activated linear alkynes with N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines. (C) Extension of push-pull activated linear alkynes to ynol ethers for efficient retro-Cope elimination reaction.

Like halogen atoms, the oxygen atom is a stereoelectronic chameleon and displays a unique dichotomic electronic state, featuring both σ-withdrawing and π-donating effects.16 Oxygen possesses an even greater electronegativity (3.44) than chlorine (3.16) on the Pauling scale17 while exhibiting a more pronounced π-donating effect. We hypothesized that these favorable properties would have a positive impact on both hydroamination kinetics and alkyne stability. Furthermore, divalency of the oxygen atom would enable the attachment of these ynol ether handles to various substrates via the oxygen atom, freeing up the propargylic position for further refinement of the alkyne’s electronics.

To study the effects of an alkoxy substituent on linear alkynes, we first set out to synthesize ynol ethers 1 and 4. We envisioned that the synthesis of 3,3-difluoroynol ether 1 could be achieved through base-mediated nucleophilic alkynyl substitution of 1-chloroalkyne 2 by alcohols. We previously observed that reactive push-pull alkynes exposed to glutathione in PBS undergo degradation via nucleophilic thiol addition to form thiol-yne-type adducts.14 Under polar aprotic solvents, we anticipated that an alkoxide would also add ipso to the halogen atom, transiently forming a vinyl anion that could then β-eliminate to afford the desired ynol ether. In analogy to nucleophilic aromatic substitution, we expected the reaction to proceed most effectively when employing the most inductively withdrawing chlorine substituent.18 1-Chloroalkyne 2 would be synthesized from the corresponding aldehyde following our prior synthesis.14 In like manner, we planned to access 3,3-difluoro-3-alkoxyynol ether 4 from 1-chloroalkyne 5, which could be derived from difluoroallene 6.

Following our retrosynthetic analysis, 1-chloroalkyne 7 was subjected to the nucleophilic alkynyl substitution reaction by triethylene glycol monomethyl ether (10) under a variety of conditions and monitored by 19F NMR spectroscopy using benzotrifluoride as an internal standard (Table 1). The desired ynol ether 11 was initially obtained in moderate yield when an excess of both alcohol 10 (1.20 equiv) and potassium hydride base (2.00 equiv) were employed in N,N-dimethylformamide at −20 °C (Table 1, entry 1). A double addition product was observed as a major by-product. Lowering the temperature to −46 °C to disfavor formation of this undesired adduct only led to poor reaction conversions despite extended reaction times (Table 1, entry 2); however, reducing the equivalents of the alcohol to a near stoichiometric amount (1.05 equiv) proved effective, providing the desired ynol ether 11 in 75% yield. Further efforts to optimize the reaction proved ineffective. Less polar or less coordinating solvents, higher or lower concentrations, and a change of the base or its counterion did not positively impact the conversion or yield of the reaction (Table 1, entries 4–6 and 9–12). We also found that the more electronegative chlorine atom was essential19 for this synthesis as its bromine and iodine counterparts 8 and 9 resulted in poor or no product formation (Table 1, entries 7 and 8). Nonetheless, the protocol for the synthesis of push-pull ynol ethers that we developed could also be applied to the reaction between 1-chloroalkyne S3 and alcohol 10 to provide 3,3-difluoro-3-alkylynol ether 26 in 70% yield.

Table 1.

Reaction optimization table for the nucleophilic alkynyl substitution reaction between alkyne 7–9 and alcohol 10.a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Entry | X | Solvent | 10 (equiv) | Temp. (°C) | Base | 7/8/9 (%)b | 11 (%)b |

|

| |||||||

| 1 | Cl | DMF | 1.20 | −20 | KH | 0 | 56 |

| 2c | Cl | DMF | 1.20 | −46 | KH | 48 | 36 |

| 3 | Cl | DMF | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 2 | 75 (72) |

| 4 | Cl | MeCN | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 13 | 51 |

| 5 | Cl | THF | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 21 | 54 |

| 6 | Cl | PhMe | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 29 | 38 |

| 7 | Br | DMF | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 27 | 15 |

| 8 | I | DMF | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 92 | 0 |

| 9d | Cl | DMF | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 14 | 53 |

| 10e | Cl | DMF | 1.05 | −20 | KH | 3 | 71 |

| 11 | Cl | DMF | 1.05 | −20 | NaH | 7 | 69 |

| 12 | Cl | DMF | 1.05 | −20 | KOtBu | 0 | 19 |

Conditions: alkyne 7, 8, or 9 (0.1 mmol, 1 equiv, 0.1 M), alcohol 10, base (2.0 equiv), 1 h.

Yields and remaining starting materials were determined by 19F NMR using benzotrifluoride as an internal standard.

Reaction was performed for 2.5 h.

Concentration of 0.025 M.

Concentration of 0.3 M. PMB = p-methoxybenzyl. Temp = temperature.

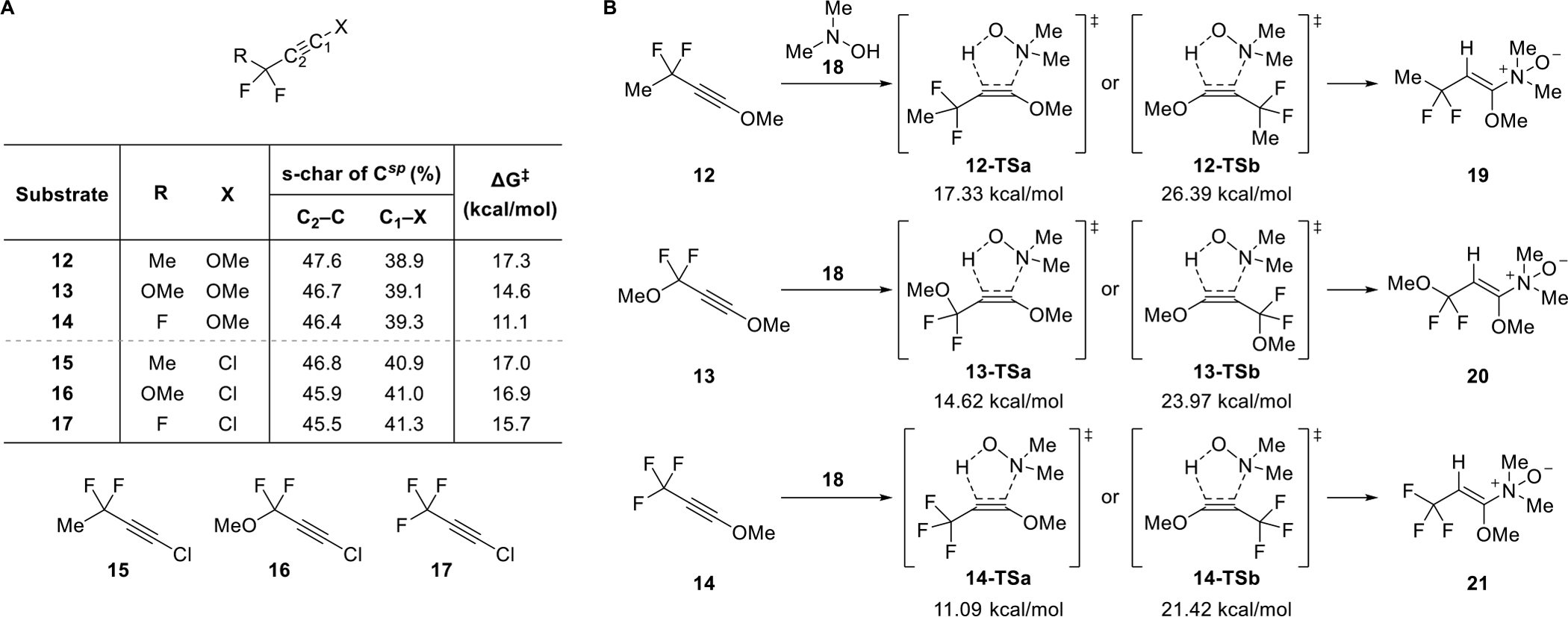

Simultaneous density functional theory (DFT)-based computational studies investigating the retro-Cope elimination reaction of these push-pull ynol ethers indicated that each of the ynol ethers 12–14 would exhibit comparable if not slightly improved reactivity over their 1-chlorinated counterparts 15–17. Calculations also confirmed that the activation free energy for the hydroamination of these novel alkynes would decrease significantly with increasing electronegativity of the atoms at the propargylic position (Figure 2A) and that these reactions would proceed with the high degree of regioselectivity that we had come to expect of push-pull alkyne hydroaminations (Figure 2B). The calculated transition state geometries reflect the presence of stabilizing hyperconjugative assistance afforded by the propargylic substituents to the forming C···N bond analogous to those observed in alkyne cycloaddition reactions.20It was also clear from these calculations that the trifluorinated analogs 14 and 17 would possess the greatest reactivity among all of the push-pull linear alkynes. While the trifluorinated 1-chloroalkyne 17 would neither be practical to synthesize nor utilize because of its potential volatility and the impossibility of appending this group to other small molecules, trifluoroynol ether 14 presented a unique opportunity. We further anticipated that the superior π-donating effects of the alkoxy substituent compared to a halogen substituent would help to better neutralize the strong π-withdrawing effects of the trifluoromethyl group and subdue its electrophilic properties.

Figure 2.

Computational studies of the retro-Cope elimination reaction between alkylynol ethers and N,N-dimethylhydroxylamine. (A) The percent s-character (s-char) of the sp-carbons of various ynol ethers and 1-chloroalkynes as well as the activation free energies (ΔG‡) for their reaction with hydroxylamine 18 were calculated. (B) Computational reaction models evaluating the reactivity and regioselectivity of alkylynol ethers are depicted.

Based on these computational studies, we proceeded to synthesize trifluorinated ynol ether 24. The synthesis commenced with the nucleophilic alkenyl substitution of alcohol 10 into 1,1,2-trichloro-3,3,3-trifluoroprop-1-ene (22) using potassium hydride in DMF at 0 °C to provide enol ether 23 in 72% yield as a 2.15:1 mixture of E:Z stereoisomers (Scheme 2). Lithium halogen exchange with n-butyllithium in diethyl ether at −115 °C followed by β-elimination then afforded ynol ether 24 in 61% yield. Low temperatures were essential for minimizing undesired addition of the alkyllithium reagent into the ynol ether product.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 3,3,3-trifluoroynol ether 24.

With the three push-pull ynol ether compounds 11, 24, and 26 in hand, we investigated the kinetics of the hydroamination reaction. Second-order rate constants were determined using equimolar N,N-diethylhydroxylamine in CD3CN at 20 °C by 19F NMR spectroscopy, and 3,3-difluoroynol ether 11 and 3,3-difluoro-3-alkoxyynol ether 26 provided rate constants of 0.23 M−1s−1 and 0.61 M−1s−1, respectively. These values were comparable to those of their 1-chloroalkyne counterparts (0.24–0.57 M−1s−1). As predicted, 3,3,3-trifluoroynol ether 24 was by far the fastest reacting alkyne among all linear alkynes tested to date. The starting material was fully consumed in less than 8 min, and we could not determine the second-order rate constant for this reaction by NMR under these reaction conditions. Instead, we obtained the rate constant for this reaction in methanol as the hydroamination reaction proceeds more slowly in protic than aprotic solvents. The measured rate constant for 3,3,3-trifluoroynol ether 24 was 0.56 M−1s−1 in methanol, which was 23- and 6.8-fold faster than the reaction with 3,3-difluoroynol ether 11 and 3,3-difluoro-3-alkoxyynol ether 26, under identical conditions.

We next evaluated the stability of ynol ethers 11, 24, and 26 under physiologically relevant conditions (Figure S1–S6). 3,3-Difluoroynol ether 11 showed no degradation in 50% CD3CN/PBS (pH 7) over 24 h, and the ynol ether also proved to be remarkably stable to thiols, degrading with a half-life of approximately 125 h in the presence of 2 mM glutathione. The ynol ether was significantly more stable under these conditions than 1-chloroalkyne 7 from which it was derived, which displayed a half-life of 43 h. On the other end of the spectrum, the 3,3,3-trifluoroynol ether 24 displayed excellent stability in water as it was >90% intact over 24 h; however, its half-life was merely 24 min in the presence of 2 mM glutathione. Most surprisingly, we found that the ynol ether with intermediate reactivity faced the greatest stability issues. 3,3-Difluoro-3-alkoxyynol ether 26 degraded with a half-life of 7.1 h in 50% CD3CN/PBS (pH 7) even in the absence of any thiols. Its half-life in the presence of 2 mM glutathione was comparable at 6.5 h. It is likely that the strong electron donating effects of the terminal and propargylic oxygen atoms on this substrate result in a more labile fluorine atom at the propargylic position than in previously evaluated push-pull alkynes, leading to its hydrolysis.

In this report, we described the synthesis of push-pull-activated alkynes featuring ynol ethers. Synthetic access to difluorinated and trifluorinated ynol ethers enabled us to explore the reactivity of these activated alkynes. We found that each of the evaluated ynol ethers reacted at least as fast as their terminally halogenated counterparts. Notably, the 3,3,3-trifluoroynol ether reacted faster with N,N-diethylhydroxylamine than any other push-pull-activated alkyne tested to date. Its second order rate constant of 0.56 M−1s−1 in protic solvents rivals the fastest strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloadditions and is even higher in aprotic environments. Unfortunately, we also discovered that some of these ynol ethers had liabilities with respect to stability. The 3,3,3-trifluorinated variant, while stable in aqueous solutions, is too electrophilic and rapidly reacts with cellular nucleophiles. The 3,3-difluoro-3-alkoxyynol ether was not stable in aqueous solutions whether thiols were or were not present. We did find, however, that the 3,3-difluoroynol ether displayed remarkable stability, even more so than its 1-chloroalkyne precursor, and could serve as a suitable alternative for the terminally halogenated push-pull alkynes in bioorthogonal applications. Nonetheless, in applications outside the strictest constraints of a biological system, each of these ynol ethers represent highly effective click reagents that engage in a rapid, uncatalyzed ligation reaction between minimal components.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of push-pull-activated ynol ethers.

Scheme 3.

Ynol ether hydroamination reaction kinetics. Second order rate constants were determined by 19F NMR for the reaction in CD3CN (red) and methanol (blue). ND = not determined. *The reaction was too fast to be monitored by 19F NMR spectroscopy under the conditions.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NIH NIEHS (1DP2ES030448) and the Claudia Adams Barr Program for Innovative Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Sletten EM and Bertozzi CR, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2009, 48, 6974; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Takayama Y, Kusamori K and Nishikawa M, Molecules, 2019, 24, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) George JT and Srivatsan SG, Chem. Comm, 2020, 56, 12307–12318; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Agard NJ and Bertozzi CR, Acc. Chem. Res., 2009, 42, 788–797; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Laguerre A and Schultz C, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol, 2018, 53, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Moses JE and Moorhouse AD, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2007, 36, 1249–1262; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xi W, Scott TF, Kloxin CJ and Bowman CN, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2014, 24, 2572–2590. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann S, Biewend M, Rana S and Binder WH, Macromol. Rapid Commun, 2020, 41, 1900359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baskin JM, Prescher JA, Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Chang PV, Miller IA, Lo A, Codelli JA and Bertozzi CR, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A, 2007, 104, 16793–16797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Jewett JC, Sletten EM and Bertozzi CR, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2010, 132, 3688–3690; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dommerholt J, Schmidt S, Temming R, Hendriks LJA, Rutjes FPJT, van Hest JCM, Lefeber DJ, Friedl P and van Delft FL, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2010, 49, 9422–9425; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deb T, Tu J and Franzini RM, Chem. Rev, 2021, 121, 6850–6914; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Harris T and Alabugin IV, Mendeleev Commun, 2019, 29, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Hu Y, Roberts JM, Kilgore HR, Mat Lani AS, Raines RT and Schomaker JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2020, 142, 18826–18835; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu H, Audisio D, Plougastel L, Decuypere E, Buisson D-A, Koniev O, Kolodych S, Wagner A, Elhabiri M, Krzyczmonik A, Forsback S, Solin O, Gouverneur V and Taran F, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2016, 55, 12073–12077; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Herner A, Marjanovic J, Lewandowski TM, Marin V, Patterson M, Miesbauer L, Ready D, Williams J, Vasudevan A and Lin Q, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 14609–14615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devaraj NK, Weissleder R and Hilderbrand SA, Bioconjugate Chemistry, 2008, 19, 2297–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson DM, Nazarova LA, Xie B, Kamber DN and Prescher JA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 18638–18643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackman ML, Royzen M and Fox JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2008, 130, 13518–13519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang D, Cheung ST, Wong-Rolle A and Kim J, ACS Cent. Sci, 2021, 7, 631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang D, Lee S and Kim J, Chem, 2022, 8, 2260–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang D and Kim J, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2021, 143, 5616–5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang D, Cheung ST and Kim J, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2021, 60, 16947–16952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Ciganek E, Read JM and Calabrese JC, J. Org. Chem, 1995, 60, 5795–5802; [Google Scholar]; (b) O’Neil IA, McConville M, Zhou K, Brooke C, Robertson CM and Berry NG, Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.), 2014, 50, 7336–7339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vatsadze SZ, Loginova YD, dos Passos Gomes G and Alabugin IV, Chem. Eur. J, 2017, 23, 3225–3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen LC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1989, 111, 9003–9014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Zhu X-Q, Wang Z-S, Hou B-S, Zhang H-W, Deng C and Ye L-W, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2020, 59, 1666–1673; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marzo L, Parra A, Frías M, Alemán J and García Ruano JL, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2013, 2013, 4405–4409. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alabugin IV, Bresch S and dos Passos Gomes G, J. Phys. Org. Chem, 2015, 28, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Gold B, Dudley GB and Alabugin IV, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135, 1558–1569; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gold B, Shevchenko NE, Bonus N, Dudley GB and Alabugin IV, J. Org. Chem, 2012, 77, 75–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.