Abstract

Introduction:

Eating disorders (EDs) are deadly illnesses with high relapse rates, highlighting need for better interventions. Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) has been implemented supplementally for EDs, with horses utilized at many residential facilities. AAT shows promise with meta-analyses of randomized control trials (RCTs) showing significant decreases in depression, anxiety, and negative affect; however, no review to date has evaluated efficacy for EDs. Therefore, this study conducted a systematic review of primary literature to investigate the efficacy of AAT for EDs.

Method:

A systematic review was conducted via PubMed, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar, up to and including September 2021, yielding 10 studies. Therapy animals included horses (n=8), dogs (n=1), and dolphins (n=1). Populations included AAT ED therapists and patients (ages 11 to adult). The PRISMA methodology was used (registration PROSPERO CRD42021256239). Risk of bias assessment used Cochrane method for quantitative studies, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative studies, and JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports. Given study type heterogeneity, neither synthesis nor certainty assessments were conducted.

Results:

Case and qualitative studies reported improvement in cognitive flexibility, ability to relinquish control, and confidence. Quantitative studies demonstrated an inverse relationship between AAT utilization and ED symptoms post-treatment. Effect sizes, when reported, were mostly moderate. All but one study had low, or unclear, risk of bias. Limited randomization and a lack of RCTs measuring ED symptomology directly makes drawing conclusions difficult.

Conclusion:

While preliminary research indicates possible benefits of AAT as a complement to traditional ED treatment, more research is needed to establish efficacy. Future studies should employ randomized control trials and examine key mechanisms of change.

Keywords: Animal-assisted therapy, AAT, eating disorder, systematic review, equine therapy

1. Animal-assisted therapy for eating disorder treatment: a systematic review

Eating disorders (EDs) are psychological conditions characterized by abnormal eating behaviors that accompany distressing thoughts and emotions 1. These include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge-eating disorder (BED), avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), and other specified feeding and eating disorder (OSFED) formerly eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). As recently as 2014, AN alone had the highest mortality rate of all psychological illnesses, and is now second only to substance use disorders 2. Further, while enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy is seen as the “gold standard” for eating disorder treatment, across studies about 50% of patients fail to reach remission 3. Thus, EDs have deleterious effects compounded by modest remission rates, highlighting the need for effective treatments to mitigate harm.

In an attempt to increase efficacy of traditional ED treatments, various therapies are often used in conjunction, including art therapy, music therapy, relaxation therapy, and animal-assisted interventions. Of these, art therapy is the most studied, showing potential for improved quality of life and mental health outcomes 4, however despite their use, there is limited data on the value of adjunctive therapies.

Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT) is a complementary treatment approach that uses animals to assist in treating a wide range of disorders and illnesses. AAT sessions are structured and goal-oriented, as opposed to animal-assisted activities (AAA) where therapy animals casually visit patients 5. AAT often utilizes horses and dogs, but other animals can be used. Examples of AAT include having patients groom animals to explore care, nurturing, and touch and riding horses during psychotherapy to strengthen therapeutic alliances, provide grounding, and promote emotional processing 6.

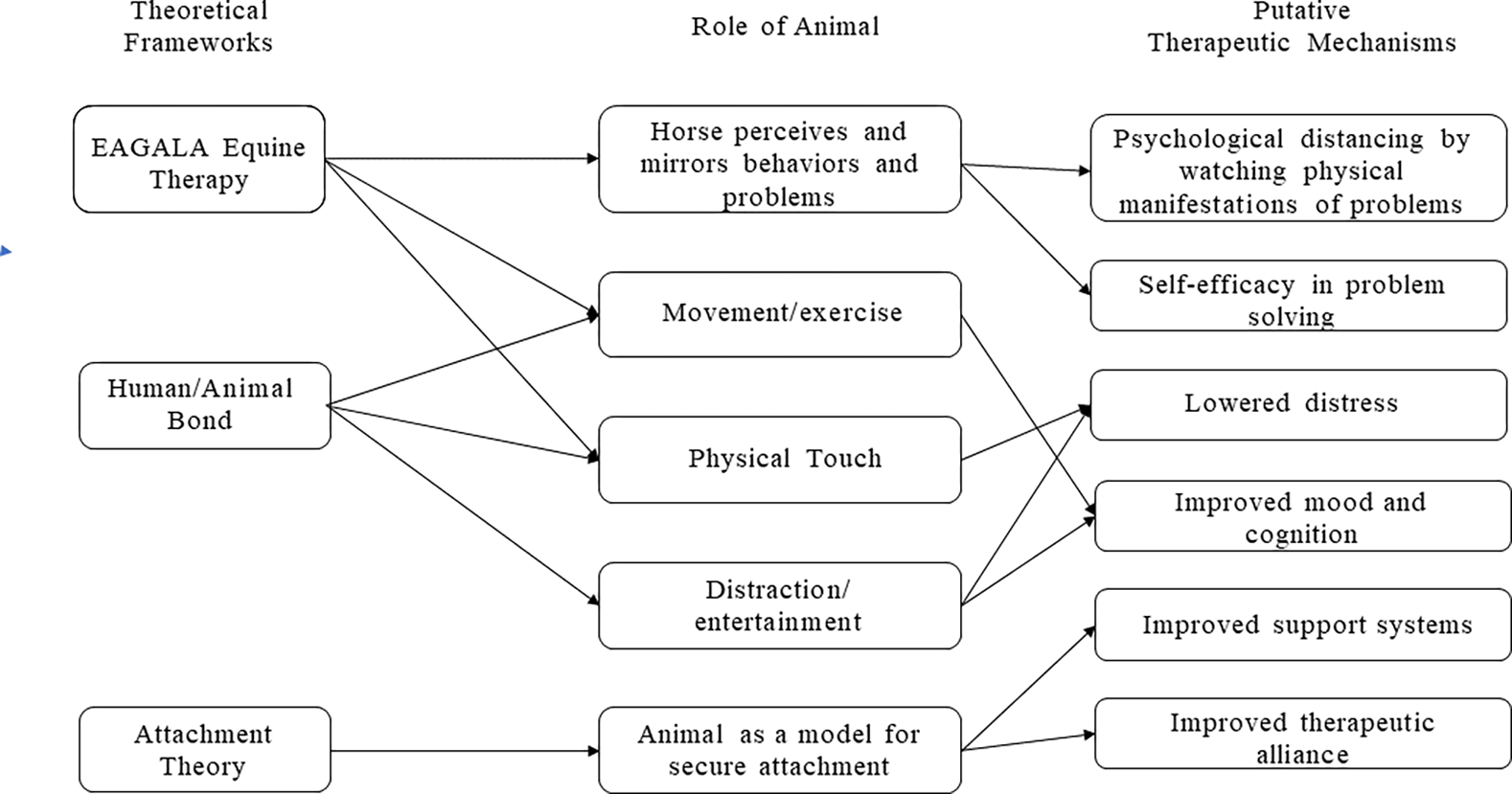

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that AAT, mostly using dogs, significantly decreased depression symptoms (standardized mean difference (SMD) 0.61 – 0.87) 7, acute anxiety (g = −0.57), and negative affect (g = −0.47) compared to controls 8. A systematic review of seven RCTs found evidence that AAT was beneficial for individuals with severe psychological disorders. As an adjunctive therapy for inpatients in these RCTs, AAT was uniquely responsible for reductions in persistent negative symptoms of schizophrenia and was beneficial as a standalone treatment for individuals with depression 9. Due to these promising findings of using AAT as a complementary treatment approach for mental illnesses, and the high relapse and mortality rates of EDs, considering the use of AAT for treatment of EDs merits further research. Determining efficacy is particularly important since AAT can be expensive due to high costs of animal care and since this approach is not currently covered by insurance. A number of theories postulate how AAT could create therapeutic change, although research is needed to determine their validity for EDs (Figure 1, adapted from 10). Of these, the most widely recognized theoretical framework for horse AAT is the Equine Assisted Growth And Learning Association (EAGALA) model, developed for AAT used in conjunction with psychotherapy for a variety of disorders 11. Based on Gestalt principles, the relationship between horse and client is seen as a physical metaphor for the client’s internal conflicts and emotions. This psychological distancing allows clients to independently process and understand their problems, bolstering self-efficacy. Horses are thought to be especially useful since they appear to mirror behaviors and emotions 12. Despite the use of EAGALA in AAT for ED treatment13–15, its efficacy and validity has not been sufficiently studied16. Another theory is attachment theory, in which the animal serves as a model of secure attachment, allowing generalization to other relationships 17. As such, AAT may also improve the therapeutic alliance 17. Given that ED treatment has a high dropout rate 18, and the alliance is one of the best predictors of dropout 19, bolstering patient-provider relationships may be essential for ED treatment engagement 18. Additionally, less secure attachment has been shown to be associated with worse ED severity20,21, and non-ED AAT patients tend to report more secure attachment as psychiatric symptoms decrease22. However, attachment has not been specifically investigated as a mechanism for ED AAT. Finally, ED treatment integrating attachment and Gestalt theories was not significantly different than CBT in one RCT23. Other hypothesized mechanisms of AAT include lowering general distress 24 such as through physical touch, distraction, and/or entertainment 10, physical activity improving mood and cognition 25, and improved social support systems beyond the patient-provider relationship 10. Since ED residential facilities limit exercise to prevent its use as a compensatory behavior, AAT maybe especially beneficial as an opportunity for healthy, monitored movement in this context, but no review to date has evaluated its effects in existing research. Thus, this study investigated the efficacy of AAT for ED treatment through a systematic review of primary literature on patient outcomes, and both patient and therapist perceptions.

Figure 1.

Potential theories of therapeutic change via AAT

Note: Adapted from Holder et al.’s model of mechanisms and frameworks of animal-assisted interventions for oncology10, EAGALA = Equine Assisted Growth And Learning Association model

2. Method

Study review was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement 26 and registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO CRD42021256239).

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria required papers to be primary studies. Within the studies, animals had to be used in a therapeutic setting for treatment, either for investigation of patient outcomes or therapist perceptions. The population had to include a clinical sample with a majority of individuals with EDs.

Exclusion criteria included reviews, meta-analyses, or theoretical frameworks without data collection. Also, studies looking at emotional support animals, service animals, or the impact of animals outside treatment were excluded.

2.2. Information sources and search

PubMed, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar were used to identify studies up to and including May 2021. No search limits were applied. Grey literature (publications beyond those in literary journals or scholarly databases) was also searched through Google. A second search was conducted in September 2021 and found no additional studies.

Search terms used were Eating disord* OR Anorexi* OR Bulimi* OR Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder OR ARFID OR Binge eat* OR Disordered eating” OR Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder OR OSFED AND Animal assisted therapy OR Animal assisted intervention OR Equine therapy OR Equine-facilitated OR Animal-facilitated.

2.3. Study selection

Article screening is displayed in Figure 2. Twenty-eight articles were initially identified. Sixteen papers were excluded after the title/abstract screen and none after the full study screen, yielding 12 articles. Two articles, Lutter27 and Lutter & Smith-Osborne28, described the same study. Two others described the same study at two different points in data collection, thus with different sample sizes29,30. Study search was conducted individually by three authors before results were compared.

Figure 2.

Study selection flowchart

2.4. Data collection

Information extracted from each paper is presented in Tables 1–4. Data collection was done by three reviewers independently before results were compared. No data were missing that needed to be solicited from study investigators, however, the Kingston15 paper was not obtainable online, so the Dublin Business School Library was contacted directly for paper access. Due to the wide variety of methodologies (i.e., case study to RCT) that do not allow for direct comparison, data were not synthesized although results tables were grouped by study type. Initially, no risk of bias assessment was planned given the expected heterogeneity of studies. This change was documented in the PROSPERO register.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors Year | Design | Population | Population statistics | Age | Sample size | Study arms or qualitative method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Cumella, 2014 | No-control variable-dose treatment outcome study | Inpatient adult women with AN, BN and EDNOS | 72 females, 33 % BN, 32% AN, 35% EDNOS 92% white, 1 each of African, Asian, Native American, and 3 multi-racial | 18–49 (M = 26, SD = 7.5) | 72 receiving trx | TAU with varying amounts of EAP |

| Dezutti, 2013 | Case studies | Female adolescents and adults at eating disorder inpatient | 7 female adolescents and adults | Not given | 7 trx | (1) EAP |

| Helm, 2009 | Multiple case study | Adult women with AN and BN | 3 females | 25, 27, and 40 | 3 trx | (1) EAP |

| Kingston, 2008 | Qualitative | Therapists who use EAP with EDs | 7 females, 3 males | Not given | 10 therapists | Structured interview assessed via thematic analysis |

| Lac, 2017 | Case study | 16-year-old with AN, just out of inpatient | 1 female | 16 | 1 trx | (1) EAP |

| Lutter, 2008; Lutter, Smith-Osborne, 2011 | Retrospect chart review, mixed methods | Inpatient adult women with AN, BN, EDNOS, staying 30+ days | 72 females | 18–50 (M=26, SD=7.5) | 72 trx | (1) EAP pre vs post With narrative analysis and thematic coding |

| Schenk, 2009 | Non-randomized pilot | Young adult women with AN, BN, and EDNOS | 32 females, BMI (Mexperimental = 18.18, Mcontrol = 20.63 | 15–23 (M=17.6, SD 2.5) | 25 trx vs 7 control | (1) dolphin-assisted therapy program vs (2) TAU |

| Sharpe, 2013 | Qualitative | Adult woman with AN, BN, and OSFED | 12 females | 19–49 | 12 trx, 6 described | (1) Equine-Facilitated Counselling group assessed via hermeneutic phenomenology |

| Stefanini, 2015 | RCT | Children and adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses (64.7% EDs) | 8 males and 9 females in each group | 11–17 at baseline (M=15.91, SD=1.73) | 34 total, 17 trx / 17 control | (1) TAU vs (2) TAU with dog animal-assisted therapy |

| Stefanini, 2016 | RCT | Children and adolescents with severe psychiatric diagnoses (60% EDs) | 9 males and 11 females in each group | 11–17 | 40 total, 20 trx / 20 control | (1) TAU vs (2) TAU with dog animal-assisted therapy |

| Træen, 2012 | Qualitative | ED therapists using group-based EAP | 5 females with 2–5 years of clinical experience in the treatment of eating disorders | 37–44 years | 6 therapists | Semi structured, assessed via qualitative content analysis |

Note: AN = anorexia nervosa, BN = bulimia nervosa, EAP = equine assisted psychotherapy, ED = eating disorder, OSFED = other specified feeding and eating disorders, RCT = randomized controlled trial, TAU = treatment as usual, trx = treatment

Table 4.

Risk of Bias - Qualitative Studies

| A. Validity of Results | B. Results | C. Value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Authors, year | 1. Clear statement of aims | 2. Qual. method apt | 3. Research design apt | 4. Recruit strategy apt | 5. Data apt for aims | 6. Consider researcher/participant relationship | 7. Consider ethics | 8. Analysis sufficiently rigorous | 9. Findings clear | 10. Describe value |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kingston, 2008 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Somewhat, but not fully explored in paper |

| Lutter, 2008 Lutter, & Smith-Osborne, 2011 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Yes, one of the first studies looking at AAT with EDs |

| Sharpe, 2013 | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Yes, although broader applicability may be limited by the heavily personal nature of the paper |

| Traen, 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Yes, explored provider perspectives on the beneficial properties of equine therapy for EDs |

Note: Y = yes, N = no, U = unclear, qual = qualitative. The CASP checklist consists of the following 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? 10. How valuable is the research?

Two reviewers independently completed risk of bias tables for quantitative, qualitative, and case studies before comparing results. For quantitative and qualitative studies risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane method (Table 3) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP; Table 4) checklist respectively. For case studies, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports was used (Table 5). Effect measures, when reported by studies, were given as r2 or η2 and reported in Table 2. Finally, given the large percentage of studies with qualitative and/or case study methods, no certainty assessment was conducted.

Table 3.

Cochrane Method Risk of Bias - Quantitative Studies

| Study | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of ppts and personnel (performan ce bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): self-report measures | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): objective measures | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Cumella, 2014 | U | U | X | U | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lutter, 2008; Lutter, Smith-Osborne, 2011 | N/a - No control | N/a - No control | U | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Schenk, 2009 | X - Not random | N/a - Not random | X | ✓ | ✓ | U | ✓ | X |

| Stefanini, 2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | U | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Stefanini, 2016 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | U | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Note: ✓= low risk, X = high risk, U = unclear risk, N/a = not applicable (i.e. no randomization)

Cumella14 - Selection protocols were not described in detail. For performance bias, the treatment team decided how much equine therapy patients received. With detection bias, the BDI, BAI, EDI are all self-reported, robust measures not likely to be influenced by blinding. However, it did not say if administrators were blinded to EAP length. No one dropped out.

Lutter27; Lutter & Smith-Osborne28 - The method consisted of retrospective review without a control group. Blinding is likely since the study was retrospective, but there was no blinding to treatment during administration. For detection bias, self-report measures are well-validated. Attrition and selection bias are of low risk given the retrospective nature.

Schnek32 - Participants were “selected” not randomized and there was no mention of blinding (plus the AAT group was the only ones who traveled to Florida). Participant drop out was not reported.

Table 5.

Risk of Bias - Case studies

| 1. Pt demographics described | 2. Pt hx described and timeline given | 3. Pt clinical condition described | 4. Dx or assessment methods and results described | 5. Trx or intervention described | 6. Post-intervention clinical condition described | 7. AEs, harms, unanticipated events described | 8. Tak-eaway lesson provided | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Dezutti, 2013 | N | N | N | N/a | Y | U | Y – pts worked through frustrations | Y |

| Helm, 2009 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y – negative experiences specific to each individual (i.e., disappoint ment) | Y |

| Lac, 2017 | U | Y | Y | N/a | Y | Y | Y – relapse and clinician relocation | Y |

Note: U = unsure if described clearly or sufficiently, Y = yes, N = no, N/a = not applicable. Pt = patient/participant, hx = history, dx = diagnosis, trx = treatment, AEs = adverse events. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports.

Table 2.

Study results.

| Quantitative | ||||||

| Authors, year | Population | Measure(s) used | Measure target | Change, effect size | Outcome type | Assessment time point |

|

| ||||||

| Cumella et al., 2014 | Inpatient adult women with AN, BN and EDNOS | Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) | Eating disorder | +Δ, N/A | Primary | Admission and discharge |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) | Depression | +Δ, N/A | Secondary | Admission and discharge | ||

| Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) | Anxiety | +Δ, N/A | Secondary | Admission and discharge | ||

| Lutter, 2008 Lutter, & Smith-Osborne, 2011 | Inpatient records or women with a length of stay ≥30 days and a primary diagnosis of AN, BN or EDNOS | Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI-2) | Eating disorder | +Δ (AN and BN), METS r2 = 0.25 − (EDNOS), N/A |

Primary | Admission and discharge |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) | Depression | +Δ, METS r2 = 0.14 | Secondary | Admission and discharge | ||

| Compendium of Physical Activities | Intensity of physical activity | N/A - predictor | Primary | Admission and discharge | ||

| Schenk et al., 2009 | Young adult women with AN, BN, or EDNOS | Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) | Psych symptoms | +Δ (time), η2 = 0.39, − (group), N/A +Δ (time × group), η2=0.13 |

Primary | Baseline and 3-month follow-up |

| Subscales: | Somatization, Obsessive Compulsive, Depression, Hostility, Paranoid Ideation, Psychoticism | +Δ (psych dimension × time), N/A | ||||

| Interpersonal Sensitivity, Anxiety, Phobic Anxiety | − (Psych dimension × time), N/A | |||||

| Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI-2) | Eating disorder | +Δ (Time), η2 = 0.34 − (Group), N/A − (Time × Group), N/A |

Primary | Baseline and 3-month follow-up | ||

| Stefanini et al., 2015 | Children and adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses (64.7 % EDs, 20.6 % mood disorders, 8.8 % schizophrenia, 5.9 % anxiety disorders) | Children Global Assessment Scale | Social and psychiatric functioning | +Δ, N/A | Primary | Beginning of intervention (T0) and the end of AAT (3 months later; T1). |

| Format of hospital care | Clinical severity | +Δ, N/A | Primary | Beginning of intervention (T0) and the end of AAT (3 months later; T1). | ||

| Ordinary school attendance | Type of school attendance (reflects level of impairment) | +Δ, N/A | Primary | Beginning of intervention (T0) and the end of AAT (3 months later; T1). | ||

| Observation of AAT | Behavior patterns during AAT | +Δ for all, N/A | Primary | Beginning of intervention (T0) and the end of AAT (3 months later; T1). | ||

| • Participation • Interaction with animal • Socialization with peers • Socialization with adults • Withdrawal behaviors • Affection towards the animal |

||||||

| Stefanini et al., 2016 | Children and adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses (67.5 % EDs, 25 % mood disorders, 5 % anxiety disorders, 2.5 % schizophrenia) | Children Global Assessment Scale | Social and psychiatric functioning | +Δ, η2 = 0.3 | Primary | Beginning and end of 3 month AAT programme |

| Youth Self Report | Emotional-behavioral symptoms | Primary | Beginning and end of 3 month AAT programme | |||

| Subscales: Internalizing Problems | +Δ, η2 = 0.14 | |||||

| Externalizing Problems | −, N/A | |||||

| Total Competence | +Δ, η2 = 0.25 | |||||

| Global Functioning | +Δ, η2 = 0.3 | |||||

| Observation of AAT | Behavioral patterns during AAT | +Δ for all, N/A | Primary | Beginning and end of 3 month AAT programme | ||

| • Participation • Interaction with the animal • Socialization with peers • Socialization with adult • Withdrawal behaviors • Affection towards the animal |

||||||

|

| ||||||

| Qualitative | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Authors, year | Population | Method | Themes | Reported effects | ||

|

| ||||||

| Kingston, 2008 | Therapists who use EAP with EDs | Qualitative study utilizing a twenty-question structured open-ended interview. Data was analyzed using thematic analysis | Structure and boundaries, changes observed in the client (although not sure if only due to EAP), therapeutic process and team approach. | Particularly effective in increasing motivation and lowering resistance to change in clients with eating disorders | ||

| Lutter, 2008 Lutter, and Smith-Osborne, 2011 | Inpatient adult women with AN, BN, EDNOS, staying 30+ days | A mixed method approach using a retrospective examination of patient records | Identifying contributing factors to the eating disorder, asking for help, problem solving, thinking positively, and verbalizing feelings of frustration. Patients wanted alternatives for those who couldn’t ride (i.e. for medical reasons), input on activities, and to have been treated more as adults. | Physical activity involved in equine therapy is safe and plays a role in eating disorder symptom improvements | ||

| Sharpe, 2013 | Adult woman with AN, BN, and OSFED | Hermeneutic phenomenology. Interviews and journal excerpts | Mindfulness or attunement to the present moment that occurred between the women and their horses, touch and movement, trusting another and trusting in oneself, as well as a giving up or sharing of control. | They felt safe and accepted being with their horses and many of the women became closer to them as they learned to move together | ||

| Træen et al., 2012 | ED therapists using group-based EAP | Semi-structured interview assessed via qualitative content analysis about their experiences with Horse-Assisted Relationship Therapy (HART) | The horse’s therapeutic properties are related to how its physical properties affect the emotional response of patients, how the horse stimulates attachment and almost becomes a model for communicating directly and clearly. | The actual horse-assisted intervention was perceived by the therapists as useful for practicing the mastery of psychological skills | ||

| Case studies | ||||||

| DeZutti, 2013 | Female adolescents and adults at eating disorder inpatient | Author’s personal observation of the interaction between horses and patients | Thinking outside of the box to create unique solutions for their problems. | Group cohesion, established trust | ||

| Helm, 2009 | Adult women with AN and BN | A combination of documentary analysis, semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions, and observation | A renewed feeling of hope, power and control over a disease that once had complete control over them, re-telling of their experience involving EAP was not only fulfilling but also very freeing. | Positive responses to EAP in the treatment of eating disorders. Significant benefits in treating the psychological issues found in women with ED | ||

| Lac, 2017 | 16-year-old with AN, just out of inpatient | Equine Facilitated Psychotherapy from an Existential Integrative approach | Increasing presence/taking up space, emotional and physical safety, feeling belonging, place to feel emotions. | Found her place in the herd in an embodied way. This sense of belonging alleviated some of her constricted ways of being in the world | ||

Note: METs = Metabolic Equivalent of a Task (a measure of exercise), controlled for length of stay; AN = anorexia nervosa; BN = Bulimia nervosa; ED = eating disorder; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; +Δ = symptoms significantly better, less pathology; −Δ = symptoms significantly worse, more pathology; − = symptoms not significantly different

Note: AN = anorexia nervosa, BN = bulimia nervosa, EAP = equine assisted psychotherapy, ED = eating disorder, OSFED = other specified feeding and eating disorder.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of included studies

Participants were between ages 11–64. Twelve articles described 10 unique studies. Quantitative investigations (n = 5, including 1 mixed-method) had treatment sample sizes from 17–72 and overall sample sizes of 32–72. Methods included an RCT, a non-randomized pilot vs treatment as usual (TAU), a no-control variable-dose treatment outcome study, and a retrospective chart review pre/post. Qualitative studies (n = 4, including one mixed-method) had samples between six and 72 participants. Methods included qualitative content analysis, hermeneutic phenomenology, narrative analysis and thematic analysis. Case studies (n = 3) described one to seven individuals. Kingston15 and Træen31 assessed ED therapists and their perceptions. The remaining studies looked at individuals with EDs or psychiatric populations with a majority of ED patients (64.5 – 67.5% participants with EDs) as in the Stefanini study29,30. No studies looked at the use of AAT for BED or ARFID. The majority of studies used horses (n = 9) with dogs29,30 and dolphins also utilized32. For some studies, AAT was not described as adjunctive, such as for those examining therapist-perceptions15,31 or for case studies on the benefits of equine therapy13,33–35. Other studies mentioned that each participant received group and individual therapies from a variety of modalities14,27,28, just individual therapy without modality specifics29,30, or “standard behavioral therapy”32. In terms of therapist perception studies, Træen did not report therapist orientations outside of the study’s horse-based therapeutic intervention (HART)31. Kingston did report orientations, but they varied widely (e.g., CBT, human-centered, psychoanalytical, activity therapy, family therapy, existential)15.

3.2. Risk of bias

Quantitative studies were relatively low risk in terms of detection, attrition, and reporting biases based on the Cochrane method (Table 3). The Schenk32 pilot was the only study with high risk of “other bias” as group sizes differed vastly, and location of treatment varied. The group that received AAT traveled to Florida for treatment, while the control group received treatment in Germany. It was also the only study high in randomization bias as participants were “selected” not randomized. Risk of performance bias was unknown for two papers on the same study as staff were not blinded, but the procedure was retrospective27,28, and high for one where staff determined how much equine assisted psychotherapy participants received14.

For qualitative studies (Table 4), the Kingston15 article had risk of bias for not adequately investigating the relationship between researcher and participants, including not addressing potential researcher bias. Also, the potential value of work could have been expanded upon. For Lutter’s articles27,28, risk of bias for the rigor of data analysis was unclear. Mainly, how themes were determined was vague beyond the overarching strategy (thematic coding and narrative analysis). Sharpe33 had risk of bias from the heavily personal nature of the hermeneutic approach limiting broader applicability. Additionally, it is unclear if this approach is apt for addressing the benefits of a psychological intervention. Finally, Træen31 does not describe potential investigator bias.

While there is no standard format for assessing risk of bias for case studies, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports provides a framework for assessing complete reporting. Based on the JBI, Helm13 did not have any areas high for incomplete reporting (Table 4). However, it was unclear if Lac34 adequately described the participant demographics. Likewise, Dezutti35 did not sufficiently describe participant demographics, participant history/timeline, or current clinical condition, whereas post-treatment clinical condition was described but it was unclear if this was sufficient.

3.3. Quantitative studies

All five studies that analyzed quantitative results found some positive effects of AAT (Table 2). Cumella14 (n = 72 inpatient adult women with AN, BN and EDNOS, no-control variable-dose treatment outcome study) found that after controlling for length of stay and admission scores, there was a significant inverse relationship between total equine minutes and discharge scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; t(71) = −2.726, p = 0.008), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; t(71) = −2.539, p = 0.01) and the four subscales of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) measured: Drive for Thinness (t(71) = −2.042, p = 0.04), Ineffectiveness as a measure of impaired self-efficacy (t(71) = −2.827, p = 0.006), Interpersonal Distrust (t(71) = −1.969, p = 0.05), and Impulse Regulation (t(71) = −3.332, p = 0.001). Results should be considered alongside the fact that selection and blinding protocols were not described in-depth, and there was no control condition. Further, the treatment team decided how much equine therapy patients received, although the retrospective nature means they did not necessarily know a study was going to occur. Effect sizes were not given and could not be calculated based on the information reported in the paper. Lutter27 and Lutter & Smith-Osborne28 (n = 72 inpatient adult women with AN, BN and EDNOS staying 30+ days, retrospective chart review mixed methods pre/post and narrative analysis) which examined the same study using regression analysis, found that as the level of physical activity and energy expenditure in equine AAT increased (measured by metabolic equivalents in the Compendium of Physical Activities [METs]), there was a significant decrease in BDI-II discharge scores (B = −.01; β = −.38, p = .002; r2 = 0.14). Increases in METs also correlated with increases in EDI-2 change scores, denoting more improvement between admission and discharge (B = .02; β = .35, p = .002; r2 = 0.25) when the participant length of hospital stay was controlled for. Notably, this was the same sample as Cumella14 but looked at METs rather than total equine minutes. Overall, risk of bias was low, but there was no control condition.

Additionally, at the end of a three month AAT intervention, Stefanini30 (n = 34 children and adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses, 64.7% EDs, RCT of TAU with and without canine AAT) found that those receiving AAT showed significant improvements in social and psychiatric functioning (measured by the Children Global Assessment Scale; t(32) = 4.57, p < .0001), significant improvements in clinical severity (measured by the format of hospital care; t(32) = 2.41, p = .02), and significant improvements in ordinary school attendance (t(32) = 2.25, p < .03), as compared to the control group of standard care alone. Similarly, Stefanini29, which is the same study as Stefanini30 but published after increased number of participants’ data was collected (n = 40 children and adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses, 67.5% EDs, RCT of TAU with and without canine AAT), examined emotional and behavioral symptoms as measured by the Youth Self Report, and found significant improvements in three of the subscales, including Internalizing Problems (t(38) = 2.60, p = 0.02, η2 = .14), Total Competence (t(38) = −3.58, p < 0.001, η2 = .25) and Global Functioning (t(38) = −4.01, p < .0001, η2 = .30) for the AAT group compared to the control group. There was no significant improvement for externalizing problems (t(38) = .12, p-value not provided). Risk of bias was lowest for this study with protocols described in-depth and the RCT methodology increasing statistical control. Lastly, Schenk32 (n = 32 adolescent and young adult women, non-randomized pilot with dolphin AAT vs TAU) found significant reductions in psychological symptoms at a three month follow-up (F(1, 30) = 19.54; p < .001; η2 = .39; ε = .99), and a significant Time × Group interaction, as the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) scores were significantly more reduced in the AAT group (F(1, 30) = 4.30; p < .05; η2 = .13; ε = .52) at the three month follow-up than the control group. In the control group, post-hoc analysis also showed no significant main effect for Time (F(1, 6) = 1.66, p = .25). Similarly, there was no significant effect for Group at either timepoint (F(1, 30) = 1.30; p = .15). Between the two time periods, there was a significant reduction in Somatization, Obsessive Compulsive, Depression, Hostility, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism (p < .05, no test statistics given), while no difference was seen for Interpersonal Sensitivity, Anxiety, or Phobic Anxiety. However, Time × Group interaction was not significant for the EDI-II (F(1, 27) = 0.26; p = .62), nor was the Group effect (F(1, 27) = 3.02; p = .16). High risk of bias, lack of randomization, and being the only study using dolphins severely limits this study’s validity and generalizability.

3.4. Qualitative studies

3.4.1. Therapist perception studies

Kingston15 utilized thematic analysis and structured, open-ended interviews to study the perceptions of therapists who use Equine Assisted Psychotherapy (EAP) for ED treatment (Table 2). Study therapists reported efficacy in increasing participants’ motivation by lowering resistance to change and increased self-awareness, trust, confidence, communication, and abilities to cede control, cope with change, and form healthy attachments. Therapists also reported that individuals do not need past experience with horses, and benefit most when horse interaction is more novel.

Træen31 assessed therapists who used group-based EAP via semi-structured interviews that were analyzed with qualitative content analysis. The study reported the horse’s therapeutic properties are thought to stem from its ability to affect patients’ emotional responses through providing physicality and buffering. Horses also become a model for communication and healthy attachment, allowing for practice of psychological skills. Finally, the context of therapy changed, creating a more symmetrical relationship between practitioner and client, increasing social connection, and simulating self-care.

3.4.2. Patient outcome studies

The Lutter studies27,28 mixed methods approach included qualitative assessment of equine assisted therapy through phenomenology-based narrative analysis and thematic coding. Themes were identified that reflected participants’ perceptions about the utility of AAT. Benefits were reported across the domains of social connection, awareness of ED factors, communication, ability to assert needs, acceptance, and cognitive flexibility. Thus, authors concluded that physical activity in equine therapy may be associated with improvements in ED symptomatology through benefitting general psychological well-being. However, patients reported wanting alternative activities when riding was not possible (i.e., weather or medical contraindication), more input on activities chosen, and more mature activities geared towards adults (some activities involved coloring and imaginative role-play).

Sharpe33 utilized hermeneutic phenomenology (emphasizing analysis of subjective experience through reflection on meaning) with interviews and journal excerpts to assess equine therapy for adult women with EDs. Reported benefits included mindfulness to the present moment, engagement in movement, increased trust, breakthroughs about the ED, and ability to relinquish control. Additionally, corporal benefits were discussed such as the ability to physically feel emotions that had been previously avoided, more positive or forgotten thoughts about their body, and physical contact that reinforced safety and warmth. However, hermeneutic phenomenology has been criticized as being vague, ambiguous, or useless as a research method36.

3.5. Case studies

As shown in Table 2, three case studies examined the effects of an AAT intervention with participants who have an ED. Dezutti35 wrote about personal observations of equine and patient interactions during EAP, and observed effects such as group cohesion and trust among patients and their horses. EAP also allowed participants to think of unique solutions for their problems, including ways to create non-physical connections with others. Additionally, women with AN and BN13 reported feelings of hope, power, and control over their ED after participation in an EAP program, and endorsed that even the re-telling of their EAP experience was “freeing” and “fulfilling.” Further, in a case study of a 16-year old with AN that underwent an Equine Facilitated Psychotherapy intervention34, feelings of belongingness, emotional and physical safety, increasing presence, and a place to feel emotions were reported.

4. Discussion

All studies reported benefits of AAT for EDs, however there is not enough evidence to conclude AAT is efficacious given the lack of RCTs measuring ED symptomology. Qualitative and case studies, examining both therapist and participant perceptions, reported possible benefits across multiple psychological skills including cognitive flexibility, ability to relinquish control, and gained confidence. Therapists also reported benefits such as healthy attachment modelling whereas patients described outcomes such as engagement in healthy movement, emotional safety allowing emotional expression, and more positive or forgotten thoughts about one’s body.

It is important to note that studies on both therapist and client perceptions may be more likely to positively describe AAT given personal involvement. However, the only reported negatives came from patients and included disappointment about not being able to ride (i.e., medical contraindications and weather), wanting more input on activities, and certain activities feeling too juvenile. Quantitative studies noted an inverse relationship between AAT and ED symptoms, except in one study which was high in risk of bias and the only one using dolphins32.

Of note, some studies excluded participants for fear and aversions towards animals and animal allergies29,30, reducing the generalizability to all ED patients, and adding to the homogeneity of reviewed studies. However, Dezutti35 and Helm13 screened for animal allergies and fear around large animals respectively, but did not use these as exclusionary criteria. Screening for fear and allergies towards animals may not occur in clinical settings, and its implementation may vary depending on the type of animal used (i.e., dolphin versus horse).

4.1. Strength of evidence

Two quantitative papers did not provide effect sizes14,30. However, Stefanini30 reported a preliminary sample, with the full-sample paper29 reporting effect sizes. Cumella14 did not report effect sizes and they could not be calculated given the no-control, variable-dose design. Papers that did report effect sizes27–29,32 found medium to large effect sizes for improving ED symptoms, depression, internalizing problems, competence, and overall functioning, although suboptimal methodologies prevent conclusions about AAT’s role in such improvements. Risk of bias varied greatly. Of note, Schenk32 had the highest risk of bias and was the only study that did not find an association between AAT and ED symptom reduction. It was also the only study to use dolphins. Thus, it is unclear if this lack of effect was due to poor study design, dolphins as a therapy animal, or AAT failing to decrease symptomatology. Risk of bias for other studies was considered low, although a few presented unclear risk. Continued research, especially well-designed studies that are of low risk of bias have the promise to yield results that will help to strengthen the evidence surrounding the efficacy of AAT.

4.2. Limitations

While the studies examined yield positive results, the range of animals used for therapy was limited. Of the ten studies, only two used animals other than horses. Further, there is an overall paucity of studies and range of study types. It is also currently impossible to determine the efficacy of dolphins and horses as AAT animals since the only RCT was conducted with dogs. Likewise, there was a lack of diversity as participants were predominantly white females. Additionally, no studies examined the use of AAT for ARFID or BED, making it impossible to generalize to these populations. Future studies that examine a more diverse sample would be valuable for determining the generalizability of AAT.

The canine RCT exclusively examined adolescents (ages 11–17), making it unclear if the addition of AAT to traditional treatment adds incremental value for all ages or just for adolescents29,30. However, the overall broad age range (11–64) of the studies is advantageous for the generalizability of results. Additionally, the canine RCT looked at a clinical population, mostly with EDs (64.7%) and measured symptoms more broadly (i.e., internalizing, functioning)29. Therefore, there is not yet evidence to suggest that AAT directly improves ED symptoms, although patients receiving AAT reported greater improvements in general psychopathology and functioning than controls, when added to traditional treatment. It is also unclear how well these results would generalize to a population of only individuals with EDs. Therefore, future research should involve RCTs examining ED symptomology changes, in a population of only ED patients. Finally, having clear rationale as to why AAT may support ED treatment, including development and refinement of theoretical frameworks (e.g., Figure 1), is crucial. If AAT is shown to be efficacious, determining mechanisms of change, including disentanglement of the roles of exercise, presence of animals, and other main constructs would be warranted.

4.3. Conclusions

Lack of controlled studies and incongruence of animals used limits both study comparison and validity, making it currently impossible to conclude if AAT is efficacious for ED treatment. However, there is some promise for its use, meriting further research. Quantitatively, evidence is strongest for using dogs for overall well-being during inpatient treatment. Qualitatively, a wide variety of psychological benefits were reported by both therapists and patients.

Highlights:

Currently there is not enough evidence to determine efficacy.

No studies employed randomization and looked at eating disorder symptomology.

Qualitative studies suggest possible benefits not provided by traditional therapy.

Evidence is best for dogs uniquely improving global functioning in adolescents.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Minnesota, Department of Psychiatry and Washington University in St. Louis, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychological & Brain Sciences.

Financial support

This work was financially supported by the National Institute of Health [grant number K08 MH120341]; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [grant number T32 HL130357]; the National Institute of Mental Health [grant number 5R21MH119417]; and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [grant number 5R01DK116616]. Funding sources had no involvement in the research conduct nor article preparation.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability

No information is supplied as a supplementary file. Given the systematic review methodology, all available data has been presented in the manuscript.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):153–160. doi: 10.1002/WPS.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atwood ME, Friedman A. A systematic review of enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(3):311–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin C, Fenner P, Landorf KB, Cotchett M. Effectiveness of art therapy for people with eating disorders: A mixed methods systematic review. Arts Psychother. 2021;76:101859. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruger KA, Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in mental health: Definitions and theoretical foundations. In: Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy. Elsevier; 2010:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driscoll CJ. Animal-assisted interventions for health and human service professionals. Published online 2020.

- 7.Souter MA, Miller MD . Do animal-assisted activities effectively treat depression? A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös. 2007;20(2):167–180. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber A, Klug SJ, Abraham A, Westenberg E, Schmidt V, Winkler AS. Animals in higher education settings: Do animal-assisted interventions improve mental and cognitive health outcomes of students? A systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. Published online 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maujean A, Pepping CA, Kendall E. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of animal-assisted therapy on psychosocial outcomes. Anthrozoös. 2015;28(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holder TR, Gruen ME, Roberts DL, Somers T, Bozkurt A. A systematic literature review of animal-assisted interventions in oncology (Part II): Theoretical mechanisms and frameworks. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420943269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Notgrass CG, Pettinelli JD. Equine assisted psychotherapy: The equine assisted growth and learning association’s model overview of equine-based modalities. J Exp Educ. 2015;38(2):162–174. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittlesey-Jerome WK. Adding equine-assisted psychotherapy to conventional treatments: A pilot study exploring ways to increase adult female self-efficacy among victims of interpersonal violence. Pract Sch J Couns Prof Psychol. 2014;3(1):82–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helm K The Effects of Equine Assisted Psychotherapy on Women with Eating Disorders: A Multiple Case Study. PhD Thesis. The University of the Rockies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cumella E, Lutter CB, Smith-Osborne A, Kally Z. Equine therapy in the treatment of female eating disorder. Published online 2014.

- 15.Kingston O Equine assisted psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders from the therapist’s perspective. Published online 2008.

- 16.Petitte S Review of Literature: Potential Benefits of Equine-Facilitated Therapy for Individuals with Eating Disorders. Recreat Parks Tour Public Health. 2018;2:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zilcha-Mano S, Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Pet in the therapy room: An attachment perspective on animal-assisted therapy. Attach Hum Dev. 2011;13(6):541–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fassino S, Pierò A, Tomba E, Abbate-Daga G. Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: a comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharf J Psychotherapy Dropout: A Meta-Analytic Review of Premature Termination. PhD Thesis. ProQuest Information & Learning; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faber A, Dube L, Knaeuper B. Attachment and eating: A meta-analytic review of the relevance of attachment for unhealthy and healthy eating behaviors in the general population. Appetite. 2018;123:410–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tasca GA. Attachment and eating disorders: a research update. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;25:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoagwood KE, Acri M, Morrissey M, Peth-Pierce R. Animal-assisted therapies for youth with or at risk for mental health problems: A systematic review. Appl Dev Sci. 2017;21(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McIntosh VV, Jordan J, Carter JD, et al. Psychotherapy for transdiagnostic binge eating: A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy, appetite-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy, and schema therapy. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt MG, Chizkov RR. Are therapy dogs like Xanax? Does animal-assisted therapy impact processes relevant to cognitive behavioral psychotherapy? Anthrozoös. 2014;27(3):457–469. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biddle SJH, Ciaccioni S, Thomas G, Vergeer I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;42:146–155. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHSPORT.2018.08.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutter CB. Equine Assisted Therapy and Exercise with Eating Disorders: A Retrospective Chart Review and Mixed Method Analysis. The University of Texas at Arlington; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lutter C, Smith-Osborne A. Exercise in the Treatment of Eating Disorders. Best Pract Ment Health. 2011;7(2):42–59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stefanini MC, Martino A, Bacci B, Tani F. The effect of animal-assisted therapy on emotional and behavioral symptoms in children and adolescents hospitalized for acute mental disorders. Eur J Integr Med. 2016;8(2):81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stefanini MC, Martino A, Allori P, Galeotti F, Tani F. The use of Animal-Assisted Therapy in adolescents with acute mental disorders: A randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21(1):42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Træen B, Moan KA, Rosenvinge JH. Terapeuters opplevelse av hestebasert behandling for pasienter med spiseforstyrrelser. Tidskr Nor Psykologforening. 2012;49:348–355. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schenk R, Schandry R, Schenk S. Animal-assisted therapy with dolphins in eating disorders. Published online 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharpe H Equine-facilitated counselling and women with eating disorders: Articulating bodily experience. Published online 2013.

- 34.Lac V Amy’s story: An existential-integrative equine-facilitated psychotherapy approach to anorexia nervosa. J Humanist Psychol. 2017;57(3):301–312. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeZutti JE. Eating disorders and equine therapy: A nurse’s perspective on connecting through the recovery process. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2013;51(9):24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermeneutics Kakkori L. and Phenomenology Problems When Applying Hermeneutic Phenomenological Method in Educational Qualitative Research. Philos Inq Educ. 2009;18(2):19–27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No information is supplied as a supplementary file. Given the systematic review methodology, all available data has been presented in the manuscript.