Abstract

In experimental visceral leishmaniasis, acquired resistance to intracellular Leishmania donovani is Th1 cell cytokine dependent and largely mediated by gamma interferon (IFN-γ); the same response also permits conventional antimony (Sb) chemotherapy to express its leishmanicidal effect. Since the influxing blood monocyte (which utilizes endothelial cell ICAM-1 for adhesion and tissue entry) is a primary effector target cell for this cytokine mechanism, we tested the monocyte's role in host responsiveness to chemotherapy in mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions. Mutant animals failed to develop any early granulomatous tissue response in the liver, initially supported high-level visceral parasite replication, and showed no killing after Sb treatment; the leishmanicidal response to a directly acting, alternative chemotherapeutic probe, amphotericin B, was intact. However, mutant mice proceeded to express a compensatory, ICAM-1-independent response leading to mononuclear cell influx and granuloma assembly, control over visceral infection, and the capacity to respond to Sb. Together, these results point to the recruitment of emigrant monocytes and mononuclear cell granuloma formation, mediated by ICAM-1-dependent and -independent pathways, as critical determinants of host responsiveness to conventional antileishmanial chemotherapy.

The peripheral blood monocyte appears to play a particularly important host defense role in experimental visceral leishmaniasis, a disseminated intracellular protozoal infection in which resident tissue macrophages are the primary targets (3, 19, 22). Blockade of monocyte influx, achieved by treating Leishmania donovani-infected mice with a monoclonal antibody (MAb) directed at the β2 integrin, type 3 complement receptor (CR3, CD11b/CD18, Mac-1), deprived parasitized tissues of this effector cell and initially impaired three interrelated mechanisms: granuloma formation, the capacity to respond to gamma interferon (IFN-γ) with intracellular parasite killing, and acquired resistance (3). Conversely, treating mice with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induced myelomonocytic cell influx into the tissues, strikingly enhanced granuloma formation at infected foci, and resulted in parasite killing (20).

The present report extends the analysis of the host defense role of the infiltrating monocyte and monocyte-directed granuloma assembly to this cell's action in the response to antileishmanial chemotherapy. In contrast to two other agents now in clinical use, amphotericin B and miltefosine (18, 23, 24), the in vivo leishmanicidal efficacy of pentavalent antimony (Sb), the conventional treatment for visceral leishmaniasis (25), requires an intact host T-cell (Th1 cell)-dependent response. Thus far, characterization of this mechanism indicates obligatory roles for T cells and a cytokine network involving endogenous interleukin 12 (IL-12), IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (17, 23, 26, 27).

The latter two inflammatory cytokines are well recognized in activation of both monocytes and resident macrophages to express enhanced antileishmanial effects (22, 23, 26, 31, 40, 41). However, these same cytokines also influence monocyte trafficking in the microcirculation and transendothelial cell migration (7–9, 38) and thus help to deliver these effector phagocytes into infected tissue sites and foster granuloma assembly (26, 40). These events appear largely regulated via initial endothelial cell adhesion mechanisms including chemokine-induced effects (1, 14) and upregulation of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), the principal endothelial cell counter-receptor for monocyte-expressed Mac-1 (8, 38). Given the critical actions of the blood monocyte in the L. donovani model (described above) (3), its role as a target for IFN-γ and TNF (22), and its additional capacity to accumulate Sb (16), we hypothesized that the monocyte also regulates host responsiveness to Sb chemotherapy. To test this possibility, we infected mice deficient in ICAM-1, characterized mononuclear cell influx and granuloma formation, and then administered antileishmanial treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions, on a C57BL/6 background (37), were purchased as breeders from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). These mice express three mutant isoforms of ICAM-1 (13), a state which impairs binding to Mac-1 (resulting in monocytes being unable to leave the microcirculation [11]) but apparently does not interfere with binding to the T-cell-expressed β2 integrin, lymphocyte function antigen 1 (LFA-1) (11), or with the interaction of LFA-1 with other endothelial cell ligands (e.g., ICAM-2 and ICAM-3 [29, 33, 38]) (4, 11, 39). Normal C57BL/6 mice weighing 20 to 30 g (Jackson Laboratory) were used as controls. Mice with gene disruptions were both male and female; normal mice were female. Animals were 8 to 15 weeks old when challenged with L. donovani.

Visceral infection and granuloma development.

Groups of three to five mice were injected via the tail vein with 1.5 × 107 hamster spleen-derived L. donovani amastigotes (1 Sudan strain) (23). Visceral infection was monitored microscopically using Giemsa-stained liver imprints in which liver parasite burdens were measured by counting the number of amastigotes per 500 cell nuclei and multiplying by the liver weight in milligrams (Leishman-Donovan units [LDU]) (23). The granulomatous response to infection in the liver was assessed in histologic sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Granuloma formation was scored as follows: (i) none—single or fused parasitized Kupffer cells with no mononuclear cell infiltrate; (ii) developing—some cellular infiltrate at the parasitized focus; (iii) mature—a core of fused infected Kupffer cells surrounded by a well-developed mononuclear cell mantle (3, 22).

Antibiotic treatment.

Two weeks after infection (day 0), liver parasite burdens were determined, and mice then received either no treatment, a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of Sb, three i.p. injections of amphotericin B deoxycholate (AmB), or five consecutive once-daily doses of oral miltefosine by gavage (23, 24). Optimal doses of each drug were administered: Sb (sodium stibogluconate, Pentostam; Wellcome Foundation Ltd., London, United Kingdom), 500 mg/kg of body weight on day 0; AmB (Gensia Laboratories Ltd., Irvine, Calif.), 5 mg/kg on days 0, +2, and +4; and miltefosine (ASTA Medica AG, Frankfurt, Germany), 25 mg/kg on days 0 to +4 (23, 24). Seven days after treatment was started (day +7), all mice were sacrificed and liver parasite burdens were measured. Percent parasite killing was determined as (day 0 LDU − day +7 LDU in treated mice)/(day 0 LDU) × 100 (23). In some experiments, visceral infection was allowed to progress to week 4 or week 8 before Sb treatment was given, and the same evaluation was performed. Differences in liver parasite burdens were analyzed using a two-tailed Student's t test.

IFN-γ measurement.

Serum IFN-γ activity was measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Endogen, Cambridge, Mass.) with a detection limit of 50 pg/ml (40).

RESULTS

Initial kinetics and outcome of visceral infection.

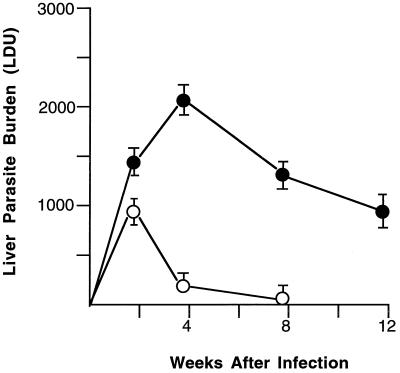

In control C57BL/6 mice, liver parasite burdens peaked at week 2 and then rapidly declined (Fig. 1) as these normal animals promptly acquired resistance and killed L. donovani (23). In contrast, in mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions, visceral infection progressed after week 2, yielding liver burdens which were ninefold higher at week 4 than those in controls. Subsequently, however, mutant animals altered their behavior, controlled intracellular replication, and reduced visceral infection, albeit in an incomplete fashion (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Course of L. donovani infection in livers of normal C57BL/6 mice (open circles) and mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions (solid circles). Results (mean LDU ± standard errors of the means at weeks 2, 4, and 8 are from three experiments (n = 9 to 11 mice per group), one of which was extended to week 12 in ICAM-1-deficient animals (n = 4 mice). P < 0.05 for mutant versus control mice at weeks 4 and 8.

Granuloma assembly.

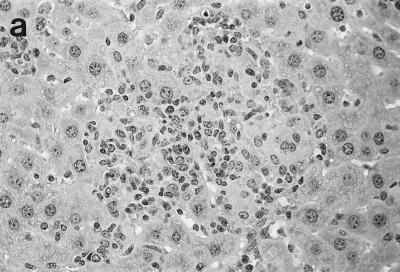

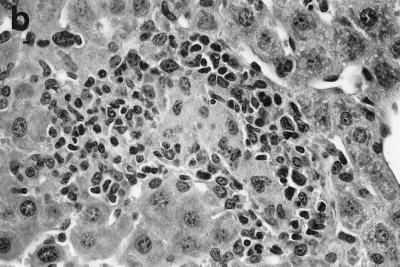

Two weeks after challenge, 92% of infected liver foci in control C57BL/6 mice had attracted mononuclear cells; histologic scoring indicated developing granulomas at 69 ± 5% of foci and mature granulomas at 23 ± 4% (Table 1; Fig. 2a). By week 4 (Fig. 2b), 70% of parasitized foci were composed of either mature or “empty” granulomas (structures devoid of visible amastigotes); by week 8, three-quarters of the tissue cellular collections in normal mice were parasite free.

TABLE 1.

Liver granuloma formation in L. donovani-infected mice

| Tissue response | % Infected foci showing the indicated responsea at various times after infection in:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal C57BL/6 mice

|

Mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions

|

|||||

| 2 wks | 4 wks | 8 wks | 2 wks | 4 wks | 8 wks | |

| No reaction | 8 ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 95 ± 4 | 12 ± 3 | 2 ± 1 |

| Developing granulomas | 69 ± 5 | 30 ± 3 | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 76 ± 6 | 35 ± 4 |

| Mature granulomas | 23 ± 4 | 52 ± 6 | 18 ± 3 | 1 ± 1 | 12 ± 4 | 42 ± 5 |

| Empty granulomasb | 0 | 18 ± 5 | 78 ± 8 | 0 | 0 | 21 ± 5 |

Fifty consecutive infected foci were identified microscopically (objective, in 63×) in liver sections and scored for the extent of granuloma formation (see Materials and Methods). Results are from two experiments and are means ± standard errors of the means for sections from four mice per group at each time point.

Granulomas devoid of parasites.

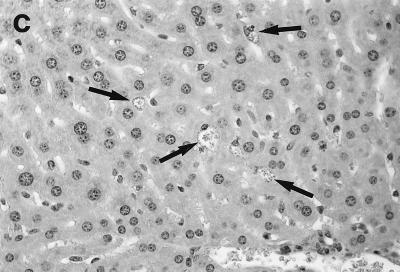

FIG. 2.

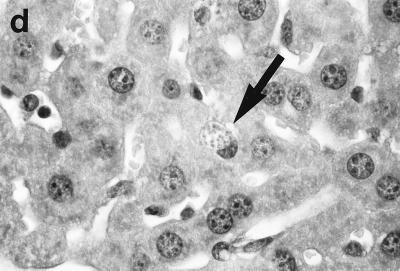

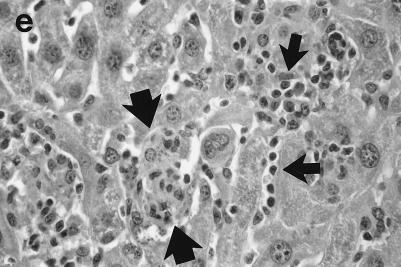

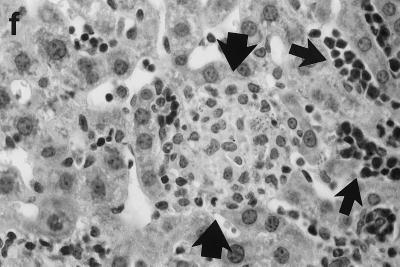

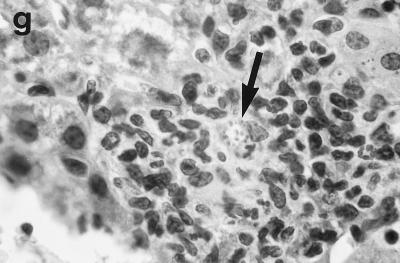

Histologic response to L. donovani infection in livers of control (a and b) and ICAM-1-deficient mice (c through g). (a and b) Normal C57BL/6 mice show influxing mononuclear cells and developing granuloma at week 2 (a) and, at week 4 (b), a mature granuloma whose surrounding mantle contains mononuclear cells with both monocyte and lymphocyte morphology. (c and d) In contrast, at week 2, there is no cellular response at parasitized Kupffer cells (arrows) in infected mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions. (e and f) Mutant mice show ICAM-1-independent early granuloma formation at week 3 (e) and week 4 (f). However, mononuclear cells (small arrows, lymphocytes and monocytes) remain largely peripheral, mostly within more distant sinusoids, and have not entered the infected focus to encircle the parasitized multinucleated granuloma core (large arrows). (g) Mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions at 8 weeks show monocyte and lymphocyte recruitment and mature-appearing but still infected granulomas (arrow). Magnifications, ×200 for panels a and c, ×500 for panel d, and ×315 for panels b and e through g.

In direct contrast, at week 2, there was essentially no cell recruitment to infected sites in livers of ICAM-1-deficient mice, and 95 ± 4% of foci consisted simply of single or fused parasitized Kupffer cells (Table 1; Fig. 2c and d). Nevertheless, after week 3, monocytes and lymphocytes appeared (Fig. 2e) and granuloma assembly emerged, beginning with formation of large multinucleated collections of Kupffer cells containing abundant amastigotes (Fig. 2f). However, except for a small number of infiltrating lymphocytes, most mononuclear cells, including those with characteristic monocyte morphology, remained peripheral to rather than encircling or entering infected foci (Fig. 2e and f). By week 4, the ICAM-1-independent response was sufficiently developed to induce early granulomas with evidence of mononuclear cell recruitment to ∼90% of parasitized sites (Table 1). By week 8, fully formed mature granulomas, containing numerous monocytes, were present at 63% of inflammatory foci (Fig. 2g); ∼20% of these granulomas were parasite free.

Response to chemotherapy.

To determine if monocyte influx and initial granuloma formation altered the response to chemotherapy, 2-week-infected mice were treated with AmB, miltefosine, or Sb using established protocols (23, 24). ICAM-1-mutant mice responded to AmB with high-level leishmanicidal activity (Table 2). In a single experiment, these animals also responded to oral miltefosine, showing 71% L. donovani killing 7 days after treatment began versus 81% killing in C57BL/6 controls (n = 3 mice per group) (data not shown). However, while normal mice reduced liver parasite burdens by 85% after a single injection of Sb (500 mg/kg), ICAM-1-deficient animals showed only 3% killing after the same treatment (Table 2). To exclude an altered dose response, 2-week-infected ICAM-1 mutants were also given high-dose Sb (three injections of 500 mg/kg on alternate days). Mutant animals also failed to respond to this regimen with meaningful leishmanicidal activity (8% killing).

TABLE 2.

Effect of chemotherapy in ICAM-1 knockout mice

| Mice and treatment | Liver parasite burden (LDU)

|

% Killing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day +7a | ||

| Treatment started 2 wk after infectionb | |||

| C57BL/6 mice | |||

| No treatment | 902 ± 125 | 1,097 ± 92 | 0 |

| Sb (500 mg/kg, once) | 132 ± 39** | 85 | |

| AmB | 73 ± 24** | 92 | |

| ICAM-1-deficient mice | |||

| No treatment | 1,507 ± 159 | 1,748 ± 100 | 0 |

| Sb (500 mg/kg, once) | 1,466 ± 129 | 3 | |

| Sb (500 mg/kg, three times) | 1,386 ± 156 | 8 | |

| AmB | 239 ± 64** | 84 | |

| ICAM-1-deficient mice, treatment started 4 or 8 wk after infectionc | |||

| Wk 4 | |||

| No treatment | 2,254 ± 213 | 2,398 ± 191 | 0 |

| Sb (500 mg/kg, once) | 712 ± 102** | 68 | |

| Wk 8 | |||

| No treatment | 1,326 ± 152 | 1,180 ± 156 | 11 |

| Sb (500 mg/kg, once) | 252 ± 51 | 81 | |

**, P < 0.05 versus day 0 LDU value.

Two weeks after L. donovani challenge (day 0), mice received no treatment, a single injection of 500 mg of Sb/kg, three alternate-day injections of 500 mg of Sb/kg (ICAM-1-deficient mice), or three alternate-day injections of 5 mg of AmB/kg. Results are means ± standard errors of the means from three experiments for 9 to 11 mice at each time point except for ICAM-1-deficient mice treated three times with Sb (two experiments, n = 6 mice).

Treatment with a single injection of Sb (500 mg/kg) was delayed until either 4 or 8 weeks after L. donovani challenge. Results in 4-week-infected mice are from two experiments (n = 6 to 7 mice); results in 8-week-infected mice are from one experiment (n = 3 mice).

Restoration of responsiveness to Sb.

The observation that ICAM-1-deficient mice expressed a compensatory, although less efficient, pathway for mononuclear cell recruitment provided a separate opportunity to test the relationship between monocyte influx and granuloma assembly and responsiveness to Sb. Since granuloma development in 4-week-infected mutant mice appeared roughly comparable to that in 2-week-infected, Sb-responsive C57BL/6 mice (Table 1), we hypothesized that Sb-induced leishmanicidal activity should be expressed by week 4 despite disruption of ICAM-1. Results from two experiments (Table 2), in which mutant mice were treated with a single dose of Sb (500 mg/kg) at week 4, supported this hypothesis: liver parasite burdens were reduced by 68% in response to the same Sb regimen which produced only 3% killing in 2-week-infected gene-deficient mice. In addition, in a single experiment, in which treatment of ICAM-1-deficient animals was delayed to week 8, at a time when the majority of infected liver foci were comprised of mature or empty granulomas (Table 1), the response to a single injection of Sb appeared to be accentuated further (Table 2). While liver parasite burdens declined by 11% in untreated mice during the 7-day observation period, Sb-treated mutant mice showed an 81% decrease.

IFN-γ production.

ICAM-1 may also act in a T-cell-costimulatory mechanism via LFA-1 (12, 28, 35–37, 42); thus, ICAM-1-deficient mice might have failed to respond to Sb because of defective cytokine production, in particular, defective IFN-γ secretion. T-cell-derived IFN-γ, another endogenous cofactor required for Sb's killing effect (23), likely supports Sb's action by enhancing monocyte tissue recruitment (e.g., via upregulation of ICAM-1 [7, 8, 14, 38]), attracting T cells (10, 14, 21, 34), activating recruited monocytes to exert intracellular antileishmanial effects (3, 22), and/or stimulating monocyte uptake of Sb (16). However, there was no defect in IFN-γ production in mice with ICAM-1 gene disruptions, since levels in the sera of 2-week-infected animals (502 ± 149 pg/ml) were comparable to those in normal mice (423 ± 96 pg/ml) (two experiments; n = 4 mice per group); levels in uninfected mice in both groups were undetectable (<50 pg/ml; n = 5 mice per group). These results, consistent with intact IFN-γ (and IL-12) mRNA induction reported in the same ICAM-1-deficient mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (11), presumably reflect preserved binding sites for LFA-1 (11) or the presence of redundant T-cell costimulation mechanisms (4, 39) in L. donovani-infected mice.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that well-recognized ICAM-1-dependent events, firm endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion and transendothelial cell migration (8, 11, 37, 38), likely regulate the initial host defense action of blood monocytes in L. donovani-infected tissues and in turn the capacity to respond to Sb chemotherapy. Since neutrophils and natural killer (NK) cells (but not T cells) also express Mac-1 (CR3) (3, 38), their adhesion to activated endothelium and entry into tissue via ICAM-1 would also likely be impaired or absent in ICAM-1-deficient mice (6, 37). However, neutrophils are seldom found at week 2 or beyond in L. donovani-infected sites, and NK cells are not required for either granuloma formation or control over parasite replication in the liver (3, 22). Thus, we interpreted observations made in infected ICAM-1-deficient mice as primarily reflecting effects of inhibition of blood monocyte entry into parasitized tissue.

In the absence of early monocyte recruitment at week 2 (Fig. 2c), three principal effects were observed. (i) First, liver granuloma assembly, including monocyte-induced attraction of other key mononuclear cells (e.g., T cells [1, 3, 5, 14]), failed. Since LFA-1 binding sites are preserved in these ICAM-1-mutant mice (11), we anticipated little impairment in T-cell influx. However, the inability of monocytes to enter the infected focus and elaborate or induce local release of T-cell-attracting factors including chemokines (e.g., IFN-γ-inducible protein 10) (5, 14) may have contributed to the initial failure to recruit any mononuclear cells. It is possible that parasitized resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) also provided some level of chemoattractant signals; however, Kupffer cells do not express CR3 (32), and we made the same histologic observations in normal mice treated with anti-CR3 to block only monocyte influx (3). (ii) Second, in the absence of monocyte recruitment, intracellular infection progressed. (iii) Third, under these conditions, the host capacity to express Sb's leishmanicidal action was abolished.

The effect on host responsiveness to Sb chemotherapy was clear, therefore adding ICAM-1 and influxing blood monocytes to the complex T cell/Th1 cell-derived cytokine mechanism which determines Sb's efficacy in vivo (17, 23, 26, 27). However, responses to AmB and miltefosine in mutant mice were entirely preserved. Intact efficacy of these two alternative antileishmanial agents in the absence of monocyte recruitment and granuloma formation is quite consistent with their apparently direct killing action. AmB and miltefosine, for example, retain full experimental leishmanicidal effects in the host devoid of mature T cells or lacking activating, pro-host defense cytokines including IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF (18, 23, 24, 26, 27).

Although ICAM-1 was an essential participant early on in this model, the strict requirement for its presence in initiating granuloma assembly and defense against visceral L. donovani in the liver proved to be relatively short-lived (Fig. 1 and 2). Our experiments did not address the nature of the slowly developing, late-onset compensatory mechanism(s) which emerged in mice with gene disruptions to induce mononuclear cell influx and granuloma formation with control over parasite replication. However, CR3- and ICAM-1-independent monocyte recruitment to infected tissues has been well reported (3, 6, 30, 32). Binding of very late antigen 4 (VLA-4), a surface β1 integrin expressed on monocytes, to its endothelial cell ligand, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), for example, can mediate ICAM-1-independent endothelial cell adhesion, monocyte migration, and granuloma formation (2, 30). Other similarly acting pathways available to ICAM-1-deficient mice may include responses via ICAM-2 and ICAM-3 (2, 38).

Once monocyte influx with early granuloma formation was established at week 4 in ICAM-1 mutants, responsiveness to Sb treatment was also restored. While this result underscored the role of monocyte influx/granuloma assembly in the expression of Sb's leishmanicidal action, the actual role of the monocyte in this mechanism needs to be defined. Possible actions include elaboration of activating monokines, attraction of cytokine-secreting Th1 cells with induction of synergistic effects from monocyte/macrophage activation (17, 23, 26, 27), intracellular accumulation and altered metabolism of Sb (16), or even monocyte activation induced by Sb itself.

At the same time, the observation that ICAM-1-deficient mice developed the capacity to respond to Sb treatment also indicated that the specific responding adhesion/recruitment mechanism (ICAM-1 versus the compensatory pathway) was not necessarily relevant as long as it properly fostered accumulation of mononuclear cells at sites of L. donovani infection. In this setting, this compensatory, ICAM-1-independent mechanism readily supported host responsiveness to Sb. Nevertheless, inspection of the data in Fig. 1, showing the persistence of visceral infection to week 8 in mice with gene disruptions, also serves to reemphasize that in addition to early control over intracellular replication, ICAM-1-dependent inflammatory events set the stage for the most efficient killing of L. donovani and optimal parasite removal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to William Muller (Department of Pathology, Weill Medical College) for helpful advice about the histologic results and to C. Montelibano for technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIH research grant AI 16963.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams D H, Lloyd A R. Chemokines: leukocyte recruitment and activation cytokines. Lancet. 1997;349:490–495. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D C. The role of β2 integrins and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 in inflammation. In: Granger D N, Schmid-Schonbein G W, editors. Physiology and pathophysiology of leukocyte adhesion. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervia J, Rosen H, Murray H. Effector role of blood monocytes in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1330–1333. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1330-1333.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen J P, Marker O, Thomsen A R. T-cell-mediated immunity to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in β2-integrin (CD18)- and ICAM-1 (CD54)-deficient mice. J Virol. 1996;70:8997–9002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8997-9002.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotterell S E, Engwerda C R, Kaye P M. Leishmania donovani infection initiates T cell-independent chemokine responses, which are subsequently amplified in a T cell-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:203–214. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199901)29:01<203::AID-IMMU203>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis S L, Hawkins E P, Mason E O, Smith C W, Kaplan S L. Host defenses against disseminated candidiasis are impaired in intracellular adhesion molecule 1-deficient mice. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:435–439. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dustin M L, Rothlein R, Bhan A K, Dinarello C A, Springer T A. A natural adherence molecule (ICAM-1): induction by IL-1 and interferon-gamma, tissue distribution, biochemistry, and function. J Immunol. 1986;137:245–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etzioni A. Adhesion molecules in host defense. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1:1–4. doi: 10.1128/cdli.1.1.1-4.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henninger D D, Panes J, Eppihimer M, Russell J, Gerritsen M, Anderson D C, Granger D N. Cytokine-induced VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression in different organs of the mouse. J Immunol. 1997;158:1825–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isselkutz T B, Stolz J M, Meide P V D. Lymphocyte recruitment in delayed-type hypersensitivity: the role of IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1988;140:2989–2995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson C M, Cooper A M, Frank A A, Orme I M. Adequate expression of protective immunity in the absence of granuloma formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice with a disruption in the intracellular adhesion molecule 1 gene. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1666–1670. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1666-1670.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J J, Anthony T, Nottingham L K, Morrison L, Cunning D M, Oh J, Lee D J, Dang K, Dentchev T, Chalian A A, Agadjanyan M G, Weiner D B. Intracellular adhesion molecule-1 modulates β2-chemokines and directly costimulates T cells in vivo. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:869–877. doi: 10.1172/JCI6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King P D, Sandberg E T, Selvakumar A, Feng P, Beaudet A L, Dupont B. Novel isoforms of murine intracellular adhesion molecule-1 generated by alternative RNA splicing. J Immunol. 1995;154:6080–6093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luster A D. Chemokines—chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mielke M E A, Niedobitek G, Stein H, Hahn H. Acquired resistance to Listeria monocytogenes is mediated by Lyt-2+ T cells independently of the influx of monocytes into granulomatous lesions. J Exp Med. 1989;170:589–594. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray H W, Berman J D, Wright S D. Immunochemotherapy for intracellular Leishmania donovani infection: interferon-γ plus pentavalent antimony. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:973–979. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray H W, Oca M J, Granger A M, Schreiber R D. Successful response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis: requirement for T cells and effect of lymphokines. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:1254–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI114009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray H W, Hariprashad J, Fichtl R. Treatment of experimental visceral leishmaniasis in a T-cell-deficient host: response to amphotericin B and pentamidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1504–1505. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.7.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray H W. Blood monocytes: differing effector roles in experimental visceral vs. cutaneous leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:220–223. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray H W, Cervia J, Hariprashad J, Taylor A, Stoeckle M, Hockman H. Effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:1183–1189. doi: 10.1172/JCI117767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray H W, Hariprashad J, Aguero B, Yeganeyi H. Intracellular antimicrobial response of T cell-deficient host to cytokine therapy: IFN-γ in experimental visceral leishmaniasis in nude mice. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1309–1314. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray H W. Granulomatous inflammation: host antimicrobial defense in the tissues in visceral leishmaniasis. In: Gallin J I, Synderman R, Fearon D T, Haynes B F, Nathan C, editors. Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 977–993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray H W, Delph-Etienne S. Role of endogenous gamma interferon and macrophage microbial mechanisms in host response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:288–293. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.288-293.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray H W, Delph-Etienne S. Visceral leishmanicidal activity of hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine) in mice deficient in T cells and activated macrophage microbial mechanisms. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:795–799. doi: 10.1086/315268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray, H. W. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis: a decade of progress and future approaches. Int. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Murray, H. W., A. Jungbluth, E. Ritter, C. Montelibano, and M. W. Marino. Visceral leishmaniasis in mice devoid of tumor necrosis factor and response to treatment. Infect. Immun., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Murray, H. W., and C. Montelibano. Interleukin 12 regulates the response to chemotherapy in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Nicod L P, El Habre F. Adhesion molecules on human lung dendritic cells and their role for T-cell activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:207–214. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/7.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiss Y, Hoch G, Deutsch U, Engelhardt B. T cell interaction with ICAM-1-deficient endothelium in vitro: essential role for ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 in transendothelial migration of T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3086–3099. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<3086::AID-IMMU3086>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritter D M, McKerrow J H. Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 is the major adhesion molecule expressed during schistosome granuloma formation. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4706–4713. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4706-4713.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roach T, Kiderlen A, Blackwell J. Role of inorganic nitrogen oxides and TNF-α in killing Leishmania donovani in gamma interferon-lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages from LshS and LshR congenic mouse strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3935–3944. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3935-3944.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen H. Role of CR3 in induced myelomonocytic recruitment: insights from in vivo monoclonal antibody studies in the mouse. J Leukoc Biol. 1990;48:465–469. doi: 10.1002/jlb.48.5.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sancho D, Yanez-Mo M, Tejedor R, Sanchez-Madrid F. Activation of peripheral blood T cells by interaction and migration through endothelium: role of lymphocyte function antigen-1/intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and interleukin-15. Blood. 1999;93:886–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schall T J, Bacan K B. Chemokine, leukocyte trafficking, and inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:856–873. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Semnani R T, Nutman T B, Hochman P, Shaw S, van Seventer G A. Costimulation by purified intracellular adhesion molecule 1 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen 3 induces distinct proliferation, cytokine and cell surface antigen profiles in human “naive” and “memory” CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2125–2135. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimizu Y, Newman W, Tanaka Y, Shaw S. Lymphocyte interaction with endothelial cells. Immunol Today. 1992;13:106–110. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90151-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sligh J E, Ballantyne C M, Rich S S, Hawkins H K, Smith C W, Bradley A, Beaudet A L. Inflammatory and immune responses are impaired in mice deficient in intracellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8529–8533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Springer T A. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steeber D A, Tang M L, Green N E, Zhang X Q, Sloane J E, Tedder T F. Leukocyte entry into sites of inflammation requires overlapping interactions between the l-selectin and ICAM-1 pathways. J Immunol. 1999;163:2176–2186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor A, Murray H W. Intracellular antimicrobial activity in the absence of interferon-γ: effect of interleukin 12 in experimental visceral leishmaniasis in interferon-γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1231–1239. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tumang M, Keogh C, Moldawer L, Helfgott D, Hariprashad J, Murray H W. Role and effect of TNF-α in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1994;153:768–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkes D S, Bowman D, Cummings O W, Heidler K M. Allogeneic bronchoalveolar lavage cells induce the histology and immunology of lung allograft rejection in recipient murine lungs. Transplantation. 1999;67:890–896. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199903270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]