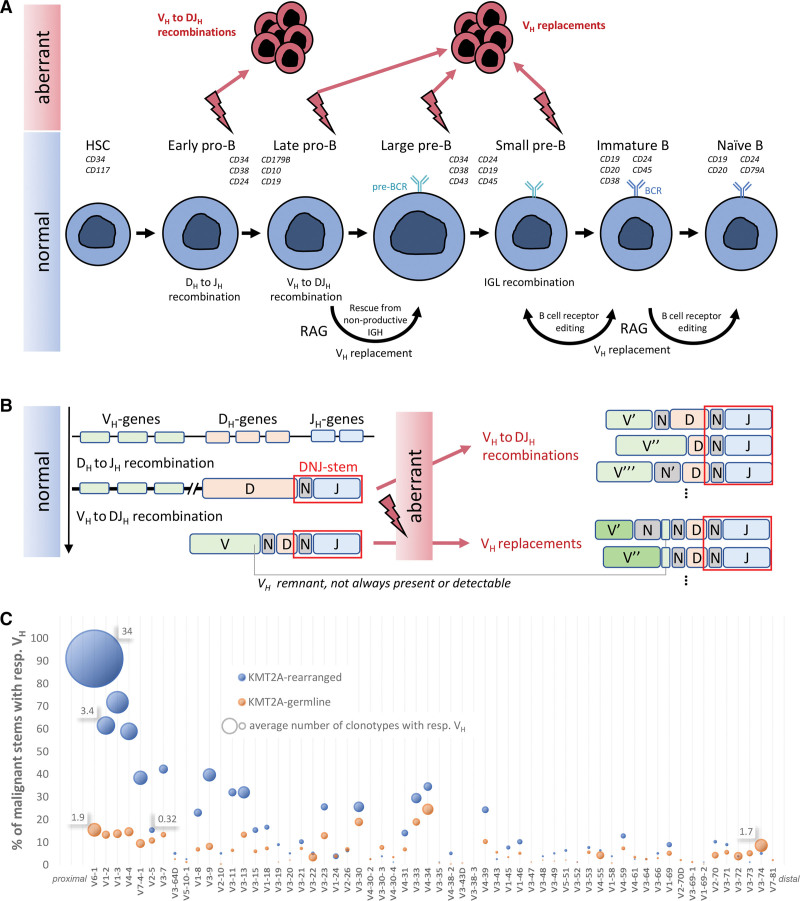

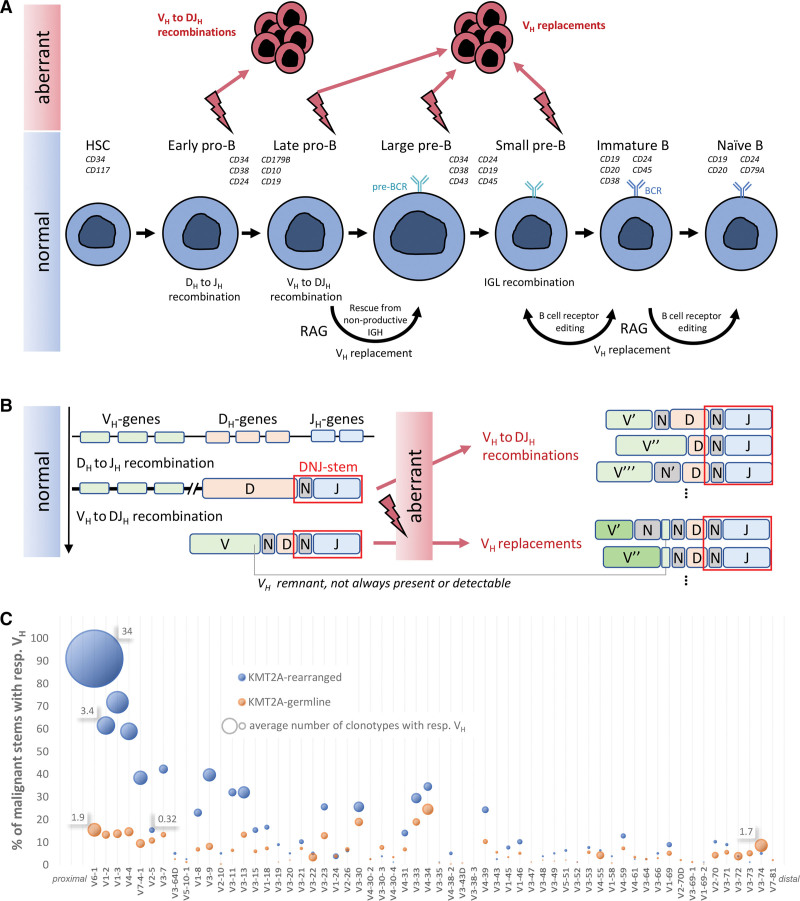

B lymphoid neoplasms originate from a single malignantly transformed immune cell, whose immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) rearrangement profile is carried by the entire expanded malignant population and mirrors its differentiation status. However, in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) and depending on the developmental stage of malignant transformation, multiple new but related IGH rearrangements may result from RAG-mediated recombination that may still be active in the malignant clone. Moreover, such phenomena complicate the identification of molecular minimal residual disease (MRD) markers and have implications for MRD monitoring. Therefore, deep analysis of IGH gene rearrangement patterns and clonal evolution mechanisms—ongoing recombination of incomplete DJH rearrangements (VH-DJH) and at a later stage also VH replacement (VH-rep), known as receptor editing in physiological B-cell development—may allow new insights into the stage of B-cell differentiation arrest of the leukemia-driving subpopulation that ultimately determines the outcome (Figure 1A), and provide more accurate MRD results.1–5

Figure 1.

Overview of the research hypothesis and results. (A) Normal B-cell development and a proposed schema for aberrant activity in the pathogenesis of BCP-ALL. (B) IGH gene recombination and VH replacement schematic. Incomplete and complete IGH rearrangements may provide the templates for aberrant multiple instances of VH to DJH recombinations and VH replacements. The DNJ-stem is highlighted in red rectangle on the rearrangement junctions, and is the same in all instances. Different genes or N regions across junctions are indicated with prime symbols. (C) VH usage of malignant stems in KMT2Arearranged and KMT2Agermline cases. x-axis: VH genes according to their order on IGH locus starting from JH-proximal; y-axis: percentage of malignant stems with clonotypes featuring respective VH (sum for each category exceeds 100% because evolving stems have multiple clonotypes); bubble area size: average number of such clonotypes in such stems, with select values provided for size reference. BCP-ALL = B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia; IGH = immunoglobulin heavy chain.

KMT2A-rearranged (KMT2Arearranged) BCP-ALL is a common occurrence in infant B-ALL affecting more than 70% of cases. It is associated with an aggressive disease course, high-risk status, and poor prognosis. Recent studies have reported immature features of the putative cell-of-origin in KMT2Arearranged cases.6–8 Single-cell transcriptome comparison between lymphoblasts and hematopoietic stem cells inferred that most KMT2Arearranged cases feature an early lymphocyte precursor stage.7 In another study, analysis of paired diagnostic and relapse samples revealed that relapses often emerge from minor subclones that were already present at diagnosis,6 where such highly subclonal architecture points to maturation arrest at a very early state with persistent IGH recombination.

Much less is known about the putative cell-of-origin in adult KMT2Arearranged BCP-ALL. We hypothesized that KMT2Arearranged cases—correlating with high-risk clinical features and corresponding to early-stage pro-B ALL—would show stem cell proximity not only in infants but also in adults. For this purpose, we studied IGH gene rearrangement profiles in 18 KMT2Arearranged cases and compared them to those of 137 cases of other molecular BCP-ALL subtypes without KMT2A gene fusions (summarized as KMT2Agermline and depicted in Suppl. Figure S1).

The information on the presence of a KMT2A fusion and corresponding subtype allocation was extracted from transcriptome sequencing performed according to published protocols.9 Patients were treated according to protocols of the German Multicenter Study Group on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GMALL). For details on the patient cohort, see Suppl. Table S1. Amplicon-based NGS with EuroClonality-NGS IGH-VJ-FR1 and IGH-DJ primers and the EuroClonality-NGS central in-tube quality/quantification control was performed using 2-step PCR and 500 ng DNA.10 Samples were sequenced on a MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with 2 × 250 bp reads. Sequences were analyzed with ARResT/Interrogate.11 For IGH clonal evolution assessment, we isolated the “DNJ-stem” (or simply “stem”) of nucleotide junctions (Figure 1B and Suppl. Materials and Methods). Thus, clonotypes sharing the same stem were considered clonally related and underwent further analysis, including a determination of whether the stem should be considered stable or evolving (see Suppl. Materials and Methods). The stem was considered “malignant” if found in ≥5% of sample reads and/or evolving at any abundance.

We detected exceptionally higher rates of clonal evolution in KMT2Arearranged (17/18, 94%) than in KMT2Agermline cases (37/137, 27%). Additionally, we observed that the VH-DJH and VH-rep mechanisms were unevenly distributed between 68 evolving stems in 18 KMT2Arearranged cases and 63 evolving stems in 137 KMT2Agermline cases: while 16 of 18 (89%) KMT2Arearranged patients showed ongoing VH-DJH and virtually no VH-rep-driven clonal evolution (2/68, 3% of evolving stems), VH-rep was a common phenomenon in the KMT2Agermline group (21/63, 33% of evolving stems) (Table 1, top part). Strikingly, the only KMT2Arearranged case without any kind of clonal evolution harbored an atypical hitherto not described KMT2A::UBASH3B in-frame gene fusion, which spans 4.3 Mbp on chromosome 11q, suggesting an interstitial deletion as a mechanism of origin (Suppl. Figure S2). A KMT2A gene fusion originating from interstitial deletion (KMT2A::ARHGEF12) has been described in rare cases of therapy-related AML and ALL as well as high-grade B-cell lymphoma identifying KMT2A deletions as driver mechanism in very specific circumstances.12 The other 17 KMT2Arearranged cases showed typical KMT2A fusions (KMT2A::AFF1 [16/18, 89%] or KMT2A::MLLT1 [1/18, 6%]) (Suppl. Table S1A).

Table 1.

IGH clonotype and clonal evolution characteristics in the KMT2Arearranged and KMT2Agermline BCP-ALL groups

Underlying that the vast majority of KMT2Arearranged evolving stems displayed ongoing VH to DJH recombination, 41 of 68 (60%) KMT2Arearranged compared to 24 of 63 (38%) KMT2Agermline evolving stems were detected in the IGH-DJ library as well, providing additional support for the hypothesis that the origin and malignant driver of KMT2Arearranged BCP-ALL is a progenitor-like population with an incomplete DJH rearrangement. This has important implications for IG-rearrangement-based MRD monitoring, especially in KMT2Arearranged cases, in which both IGH-VJ and IGH-DJ tubes should be sequenced for follow-up samples and checked for the presence of both the initially dominant and any clonally related evolved clonotypes that together compose the entirety of MRD.

We further noticed a remarkable difference in the VH gene usage between the groups. KMT2Arearranged cases showed a preferential and biased usage of the most JH-proximal human VH gene, VH6-1: 91% of malignant stems in the KMT2Arearranged group harbored at least one VH6-1-rearranged clonotype—in the KMT2Agermline group, this was the case in only 16%. Beyond that, KMT2Arearranged malignant stems with a VH6-1 gene had exceptionally high numbers of clonally related clonotypes, both compared to KMT2Agermline stems with a VH6-1 gene but also compared to stems with further downstream VH genes (Figure 1C). Generally, KMT2Arearranged evolving stems showed higher numbers and lower median abundance of related clonotypes, suggesting that VH-DJH is a highly active and ongoing process in KMT2Arearranged BCP-ALL (Table 1, bottom part).

Overall, 16 of 18 KMT2Arearranged ALLs had the immunophenotype of a pro-B ALL, all with evolving stems, whereas in the KMT2Agermline group, only 11 of 137 cases corresponded to a pro-B-ALL, of which only one case had evolving stems ((Suppl. Table S1). These data suggest that the stem cell proximity of the IGH genotype of KMT2Arearranged ALL is not fully explained by the immature immunophenotype.

We conclude that the 2 mechanisms driving IGH clonal evolution in BCP-ALL, ongoing VH-DJH recombination and VH replacement, correlate with maturation arrest in different stages of B-cell development. The latter is thought to be a physiologically legitimate rescue mechanism for pre-B cells with nonfunctional or autoreactive IGH rearrangements and has recently been linked to B-cell receptor-mediated signaling in human immature B cells.13 Ongoing VH-DJH recombination, on the other hand, is a sign of a differentiation arrest in a very early stage and takes place in virtually all BCP-ALL cases with typical KMT2A fusions, consistent with findings stating that leukemic blasts in KMT2Arearranged ALL originate from early precursor cells.8 Consentaneous with this finding, VH6-1, ubiquitously used in our VH-DJH-evolving KMT2Arearranged group, was found in fetal liver at high clonotypic abundances as part of a very early immune system ontogeny; those VH6-1-rearranged B cells reportedly persist into adulthood in the course of life-long, innate B lymphopoiesis and are thought to serve as founders of malignant transformation late in life.14 As yet another sign of fetal origin of that group, the preferential usage of DH7-27 was described in fetal human liver early B cells15—in our analysis, 9% of stems used DH7-27 in the KMT2Arearranged group compared to only 1% in the KMT2Agermline group.

In summary, we provide evidence that the cell-of-origin and malignant driver of KMT2Arearranged BCP-ALL, an aggressive disease with dismal outcome and increased risk of relapse,8 show ontogenic stem cell proximity not only in infants but also in adults. Furthermore, we report on striking similarities of its IGH rearrangement profile to fetal B cells, linking KMT2Arearranged BCP-ALL to fetal-derived early immune system ontogeny.

We also share a note of caution. The high number and low abundance of clonally related clonotypes in evolving cases have the potential to complicate or even impede both marker identification and MRD monitoring: all individual clonotypes of evolving stems may fall below traditional screening abundance thresholds at diagnosis, and different individual but related clonotypes may persist in follow-up timepoints. We therefore recommend to always analyze both IGH-VJ and IGH-DJ tubes in BCP-ALL and to check for the presence of clonally related clonotypes to avoid false-negative or underestimated MRD values, especially in KMT2Arearranged cases with a high propensity for clonal evolution of IGH rearrangements as presented herein. Accordingly, when available, the KMT2A chromosomal breakpoint should be considered as a more stable and specific MRD marker.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Hematology Laboratory Kiel staff for sample processing. The authors are indebted to the GMALL Trial Center (R. Reutzel, C. Fuchs) and participating hospitals for patient recruitment, care and logistics.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ND and MB shared senior authorship. MB and MS designed the research; NG supervised the clinical trial; MK, ND, and FD processed, analyzed, and interpreted high-throughput sequencing data; ND and KP worked on ARResT/Interrogate; LB, AH, TB, and MN analyzed and interpreted RNA-Seq data; FD, ND, MKe, and MS performed statistical analyses; MB, MS, and CDB supervised the project; FD, ND, MS, and MB drafted the first version of the manuscript; all authors read and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

MB received personal fees from Incyte (advisory board) and Roche Pharma AG, financial support for reference diagnostics from Affimed and Regeneron, grants and personal fees from Amgen (advisory board, speakers bureau, travel support), and personal fees from Janssen (speakers bureau), all outside the submitted work. MS received a personal fee from Amgen (speakers bureau), outside the submitted work. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. All the other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung (grants DJCLS R 15/11 to MB and DJCLS 06R/2019 to MS and MB, as well as by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) project number 444949889 (KFO 5010/1 Clinical Research Unit “CATCH ALL”) to LB, AH, MN, MB, and CDB.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

FD and MS contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang Z, Burrows PD, Cooper MD. The molecular basis and biological significance of VH replacement. Immunol Rev. 2004;197:231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan D, Tergaonkar V. Unraveling B cell trajectories at single cell resolution. Trends Immunol. 2022;43:210–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beishuizen A, Hählen K, Hagemeijer A, et al. Multiple rearranged immunoglobulin genes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia of precursor B-cell. Leukemia. 1991;5:657–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi Y, Greenberg SJ, Du TL, et al. Clonal evolution in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia by contemporaneous VH-VH gene replacements and VH-DJH gene rearrangements. Blood. 1996;87:2506–2512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gawad C, Pepin F, Carlton VEH, et al. Massive evolution of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in children with B precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:4407–4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardini M, Woll PS, Corral L, et al. Clonal variegation and dynamic competition of leukemia-initiating cells in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia with MLL rearrangement. Leukemia. 2014;29:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khabirova E, Jardine L, Coorens THH, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals a distinct developmental state of KMT2A-rearranged infant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med. 2022;28:743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Yu W, Alikarami F, et al. Single-cell multiomics reveals increased plasticity, resistant populations, and stem-cell-like blasts in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia. Blood. 2022;139:2198–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastian L, Hartmann AM, Beder T, et al. UBTF::ATXN7L3 gene fusion defines novel B cell precursor ALL subtype with CDX2 expression and need for intensified treatment. Leukemia. 2022;36:1676–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knecht H, Reigl T, Kotrová M, et al. ; EuroClonality-NGS Working Group. Quality control and quantification in IG/TR next-generation sequencing marker identification: protocols and bioinformatic functionalities by EuroClonality-NGS. Leukemia. 2019;33:2254–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bystry V, Reigl T, Krejci A, et al. ; EuroClonality-NGS. ARResT/Interrogate: an interactive immunoprofiler for IG/TR NGS data. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:435–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schafernak KT, Williams JA, Clyde BI, et al. Identification of KMT2A-ARHGEF12 fusion in a child with a high-grade B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Genet. 2021;258:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Lange MD, Hong SY, et al. Regulation of VH replacement by B cell receptor–mediated signaling in human immature B cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:5559–5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy A, Bystry V, Bohn G, et al. High resolution IgH repertoire analysis reveals fetal liver as the likely origin of life-long, innate B lymphopoiesis in humans. Clin Immunol. 2017;183:8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeder HW, Wang JY. Preferential utilization of conserved immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene segments during human fetal life. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6146–6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]