Abstract

The disposal of healthcare waste without prior elimination of pathogens and hazardous contaminants has negative effects on the environment and public health. This study aimed to profile the complete microbial community and correlate it with the antibiotic compounds identified in microwave pre-treated healthcare wastes collected from three different waste operators in Peninsular Malaysia. The bacterial and fungal compositions were determined via amplicon sequencing by targeting the full-length 16S rRNA gene and partial 18S with full-length ITS1–ITS2 regions, respectively. The antibiotic compounds were characterized using high-throughput spectrometry. There was significant variation in bacterial and fungal composition in three groups of samples, with alpha- (p-value = 0.04) and beta-diversity (p-values <0.006 and < 0.002), respectively. FC samples were found to acquire more pathogenic microorganisms than FA and FV samples. Paenibacillus and unclassified Bacilli genera were shared among three groups of samples, meanwhile, antibiotic-resistant bacteria Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecium, and Enterococcus faecalis were found in modest quantities. A total of 19 antibiotic compounds were discovered and linked with the microbial abundance detected in the healthcare waste samples. The principal component analysis demonstrated a positive antibiotic-bacteria correlation for genera Pseudomonas, Aerococcus, Comamonas, and Vagococcus, while the other bacteria were negatively linked with antibiotics. Nevertheless, deep bioinformatic analysis confirmed the presence of blaTEM-1 and penP which are associated with the production of class A beta-lactamase and beta-lactam resistance pathways. Microorganisms and contaminants, which serve as putative indicators in healthcare waste treatment evaluation revealed the ineffectiveness of microbial inactivation using the microwave sterilization method. Our findings suggested that the occurrence of clinically relevant microorganisms, antibiotic contaminants, and associated antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) represent environmental and human health hazards when released into landfills via ARGs transmission.

Keywords: Healthcare, Waste management, Pathogenic microbe, Antibiotic resistance, Beta-lactam, Microwave

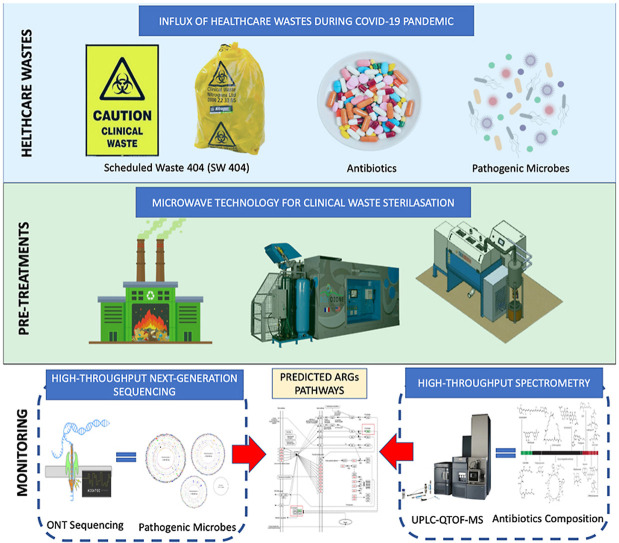

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Poor healthcare waste (HCW) management represents a major worldwide issue and is often associated with various health and environmental problems, including disease transmission and environmental pollution (Dey et al., 2023; Ekanayake et al., 2023). The disposal of HCWs containing infectious agents generated from healthcare facilities into landfills, without appropriate segregation has been widely reported in developing countries (Agwu, 2012; Khan et al., 2019). The leachate from landfills acts as a potential pathway for contaminants diffusion and has significant impacts on soil physicochemical, biological, and groundwater properties associated with agriculture activities and human health (Anand et al., 2021a, Anand et al., 2021b, Anand et al., 2021c). Unlike developed countries, developing countries face more challenges in implementing waste management systems owing to technical and economic constraints (Ferronato and Torretta, 2019). Furthermore, without proper waste treatment, coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infected wastes containing viable viruses and infectious pathogens could be a source of outbreak and pandemic (Olaniyan et al., 2022). Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a global threat where microbial pathogens continue to evolve and develop resistance to existing antibiotics, putting the world in another pandemic (Aljeldah, 2022). The extensive use of antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial infections in COVID-19 patients enhanced the prevalence of AMR, which might result in clinical complications and the development of multidrug-resistant microorganisms (Pérez de la Lastra et al., 2022).

Clinical activities such as treatment, patient assessment, and human vaccination create a considerable volume of HCW possibly contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms (Arockiam JeyaSundar et al., 2020). The quantity of HCWs increased rapidly with the development of the population, the usage of disposable medical products, and the establishment of new private clinics (Khan et al., 2019). In addition, COVID-19's aftereffects impacted the healthcare system worldwide including Malaysia (Syahida Mat Yassim et al., 2021; Ummu Afeera; Zainulabid et al., 2022; Ummu Afeera Zainulabid et al., 2021), with the obligatory use of extra personal protective equipment and laboratory materials resulted in an increase in HCW that exceeded the disposal capacity (Hantoko et al., 2021). According to Agamuthu and Barasarathi (2021), the daily HCW generation in Malaysia is estimated to be 90 metric tonnes (MT), with COVID-19 waste accounting for 27% of the increment (25 MT) during the pandemic. HCW-caused environmental pollution also represents potential infection routes for the spread of pathogens via environmental-to-human, pollution-to-human, and human-to-human transmission mechanisms (Anand et al., 2022; Anand et al., 2021). The overproduction of HCW associated with poor waste management worsens the conditions and leads to a high risk of pathogen exposure and transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the environment (Antoniadou et al., 2021; Iyer et al., 2021). Likewise, poorly managed HCWs may contribute to various health hazards and environmental pollution, hence, the performance of the HCW management system needs to be assessed to ensure the complete removal of contagious agents before being released into the environment during disposal.

Incineration has been widely practiced for solid waste treatment to destroy infectious waste and reduce waste volume through thermal destruction. In Malaysia, incinerator technology was introduced and operated on a small-scale basis on resort islands to destroy infectious waste through thermal destruction (Batterman, 2004; Nidoni, 2017). However, this technique was only used in limited quantities due to high operating costs attributed to the high moisture content of the waste and lack of technical expertise in maintaining incinerators (Abd Kadir et al., 2013). Thus, microwave technology is introduced as an alternative solution for HCW treatment due to its cost-effective and environmentally friendly properties (Yi and Jusoh, 2021). However, the application of microwave technology in HCW treatment remains understudied, and the microbiological evidence base on treatment efficiency is still limited.

While the former microbiological assessments of HCW using culture-dependent methods provided limited information, the use of high-throughput next-generation (NGS) sequencing sheds light on the identification of known and unknown microbial communities present in HCW with pinpoint precision (Egbenyah et al., 2021; Joshi et al., 2020). In this explorative study, we aimed to characterize the complete microbial communities using high-throughput NGS on Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) platform and assess the presence of antibiotic compounds in the microwave pre-treated HCW collected from three different waste operators in Peninsular Malaysia. We also investigated the correlation between the microbial abundance and the identified antibiotics, as well as profiled the antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in the pre-treated HCW. Considering that the prospect of microwave treatment has a significant impact on microbial reduction, the microbial composition and occurrence of antibiotic compounds may indicate the effectiveness of microwave technology in eliminating microorganisms and contaminants to treat hazardous HCW.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of HCW microwave treatment

Generally, 250–300 kg of collected HCW is loaded into a shredding machine to produce 5 mm to 2 cm tiny pieces of homogenous mixture of solid wastes. The shredded dry HCW wastes were then fed into an automated Microwave AMB-serial 250-Ecosteryl (AMB-Ecosteryl, Belgium) for sterilization at 100 °C and maintained close for 1 h. The treated HCW residues were stored in the holding tank and packed in residue bags prior to sample collection for this study.

2.2. Sample collection, processing, and DNA extraction

A total of 10 bags of microwaved pre-treated HCW samples were collected from three different local waste operators, namely FC (n = 3), FA (n = 4), and FV (n = 3), respectively, to obtain preliminary information and evaluate whether microbial and antibiotics contamination may be present at the specific place and time. Hence, no replicates are required. Each bag representing a different batch of treated samples was collected and kept on ice during delivery. The samples were immediately kept at −20 °C upon arrival at the laboratory to maintain the microorganisms inactive prior to subsequent molecular analysis. 10 g of each sample was obtained and transferred to 50 mL autoclaved vials. Each vial received 10 mL of 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The samples were soaked for 15 min, followed by a 10-min vortex. The solid HCW was then removed, and the supernatants were collected for further DNA extraction. The extraction process was performed using the DNeasy Powersoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol with several modifications.

2.3. DNA library preparation and amplicon sequencing

The library preparation was prepared by amplifying the full-length 16 S rRNA sequence of bacteria using S-D-Bact-0008-c-S-20 (5′-AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492 R-(5′-CGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) primers on the primer 5′ end using Nanopore partial adapter (Matsuo et al., 2021b). For fungal characterization, targeted partial 18 S and full-length ITS1–ITS2 regions were amplified using ITS9NGS (TTTCTGTTGGTGCTGATATTGCTACACACCGCCCGTCG) and ITS4 (ACTTGCCTGTCGCTCTATCTTCTCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) primers with a Nanopore partial adapter on the primer 5′ end (Tedersoo et al., 2015). The PCR was carried out via WizBio HotStart 2x Mastermix (WizBio, Korea) with the PCR condition set at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 120 s. The PCR products of the 16 S rRNA gene and ITS region were visualized on gel and purified using SPRI Bead (Oberacker et al., 2019), respectively. Subsequently, the index PCR was performed using the EXP-PBC001 kit (Oxford Nanopore, UK). The pooled barcoded libraries were gel-purified according to the manufacturer's instructions using the WizPrepTM Gel/PCR Purification Mini Kit (WizBio, Korea). The Denovix high sensitivity kit (Donovix, Wilmington, DE) was used to quantify pooled barcoded amplicons. 200 fmol of the amplicons was used to prepare the LSK110 library (Oxford Nanopore, UK), followed by 24 h of sequencing on the Nanopore Flongle flow-cell.

2.4. Raw microbial genomics data analysis

The Nanopore raw reads were basecalled and demultiplexed using Guppy v5.0.7 in high accuracy mode. The cutadapt v4.1 (Martin, 2011) was used to filter raw reads and remove the identified forward and reverse primer sequences. The filtered reads were then processed using NanoCLUST (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020) for read clustering, consensus generation, and abundance estimation. An Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASVs) table was generated from the NanoCLUST cluster output table, followed by the removal and identification of chimera using uchime de novo (Edgar et al., 2011). A q2-feature-classifier (Bokulich et al., 2018), which was trained on the latest Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) release r202 full-length 16 S rRNA database (Parks et al., 2020), was used to classify the non-chimeric consensus full-length 16 S rRNA gene sequences of bacteria. Whereas for fungal taxonomy classification, ITS1-5.8 S-ITS2 sequences were taxonomically classified using a q2-feature-classifier (Bokulich et al., 2018) that was trained on the latest UNITE ITS v8.3 database (Abarenkov et al., 2021; Nilsson et al., 2019). The unclassified sequences were then extracted using ITSx and blasted against the SILVA 138 SSU database (Quast et al., 2013) using qiime 2 classify-consensus-blast tool (Bolyen et al., 2019). The respective ASV table, taxonomic assignment, and sample metadata were manually formatted to make them compatible for data analysis on the MicrobiomeAnalyst webserver (Chong et al., 2020) with several parameters modification for bacterial (Tay et al., 2021) and fungal (Tay et al., 2022) community analysis.

Comprehensive statistical analysis of microbiome data was performed using MicrobiomeAnalyst (Chong et al., 2020; Dhariwal et al., 2017) through the Marker-Gene Data Profiling (MDP) module for bacterial and fungal composition comparison across different groups with adjusted parameters (Jaswal et al., 2019). Briefly, the low-count features were filtered with a minimum count cut-off of four based on 20% prevalence mean values. Features having a variation of less than 10% were excluded based on the interquartile range. The data was then adjusted using cumulative sum scaling (CSS) (Dhariwal et al., 2017). The Shannon and Observed indexes were used to assess alpha diversity, while the Jaccard Index and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices were used to assess beta diversity, with p < 0.05 considered significant. LEfSe was used to identify the features with significant differential abundance between the three groups at p < 0.05. The annotated genomic information of opportunistic pathogens was searched against the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) (https://www.bv-brc.org/) to determine the pathogenicity of the identified bacteria.

2.5. Sample preparation for ultra-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOF-MS) analysis

The sample preparation for metabolomic analysis was prepared according to the protocol described by Huang et al. (2020) with minor modifications. Briefly, 500 μL of liquid suspension was obtained and transferred to a new 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. The suspension was centrifuged at 13,500×g for 3 min and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter. The filtrate was mixed with 500 μL of methanol/acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) in a 2 ml microcentrifuge tube and vortex-mixed for 60 s. The solution was incubated at −20 °C for 20 min. After that, the sample was then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C using Allegra X-22 R refrigerated centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, USA) to obtain supernatant. The supernatant was transferred into vials for UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis.

2.6. UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis

A Vion IMS LCQTOF mass spectrometer (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) with a Waters Acquity ultra-performance LC system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a photodiode array (PDA) detector was used for chromatographic analysis as described in (Siew et al., 2022). The sample analyte was separated using an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C8 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) column containing two mobile phases A (0.1% formic acid in distilled water) and B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) with flow rate at 0.5 mL/min. Temperatures in the column and sample were kept constant at 40.0 °C and 20.0 °C, respectively.

The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode and the electrospray ionization (ESI) source was set at the default parameters. A high definition TOF MS was employed for MS/MS data acquisition in high sensitivity mode. The TOF MS scan mass ranged from 50 m/z to 1000 m/z, with a total scan accumulation time of 20 min at 0.20 s/spectra. The high collision energy started at 10 eV and peaked at 40 eV, with an average collision energy of 4 eV. Data processing software (UNIFI) was used to classify the identified compounds based on the mass error where a good match is (±5 mDa) and a poor match is (±10 mDa).

2.7. ARGs prediction and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis

Antibiotic Resistance Gene Online Analysis (ARGs-OAP) v2.0 was used to predict ARGs in HCW amplicon datasets by annotating the sequences to the integrated Structured Antibiotic Resistance Genes (SARG) database using the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) (Yin et al., 2018). Initially, the full-length amplicon sequences (∼1600 bp) were pre-screened for potential ARGs based on 16 S rRNA regions using UBLAST before being aligned to SARG using BLASTX on the web platform (Yang et al., 2016). Then, the metadata file and extracted data sequences comprising sequences with matched classification were uploaded into the ARGs-OAP web server for identification of ARGs using parameters with a cut-off alignment length of 25 nucleotides, e value of 1e−7, and 50%–80% alignment identity. The ARGs abundances were normalized by 16 S rRNA genes and the output listing the abundance of ARGs with targeted ARG type and subtypes were expressed as 16 S rRNA gene copy number based on equation (Eq. (1)) as described by Qian et al. (2021) and Yang et al. (2016).

| (1) |

NARG-like sequence is the number of ARG-like sequences annotated to the specific ARG reference sequences; Lreads refers to the length of reads; LARG reference sequence is the nucleotide sequence length of the particular ARG reference sequence; N16S sequence denoted as the number of the 16 S rRNA gene sequences; and L16S sequence is the full length of 16 S rRNA gene. Meanwhile, the functional genome annotation of amplicon data against the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database was accomplished by using the single-directional best hit (SBH) method at the web-based KEGG Automated Annotation server (KAAS) to determine the presence of metabolic pathway maps for antibiotic resistance development (Moriya et al., 2007).

2.8. Statistical analysis

For multivariate data analysis, the relationships between the identified antibiotic compounds and the microbiome community were assessed by Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which was done using the ggplot package from R statistical software (software R V4.1.1). The PCA was also performed on the correlation coefficient matrix using ggcorr function and the results were expressed as Pearson's similarity coefficient values. Features with a correlation of more than 0.5 were tested further with Pearson's coefficient using cor. test () function, with p < 0.05 deemed significant.

3. Results

A total of 10 FASTQ files were generated by ONT long read sequencing corresponding to the bacterial and fungal domains. The sequence read counts mapped to the ASVs resulted in 253 bacterial ASVs and 55 fungal ASVs. The taxonomic classification of ASVs at the phylum and genus levels for bacterial and fungal taxa is shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Identified total read counts and taxonomic classification of ASVs at the phylum and genus levels for bacterial and fungal in the HCW samples.

| Total Read Counts | ASVs | Phylum Level | Genus Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 267,043 | 253 | 4 | 42 |

| Fungi | 408,182 | 55 | 4 | 31 |

3.1. Microbial community profiling HCW samples

3.1.1. Overview of bacterial composition and diversity

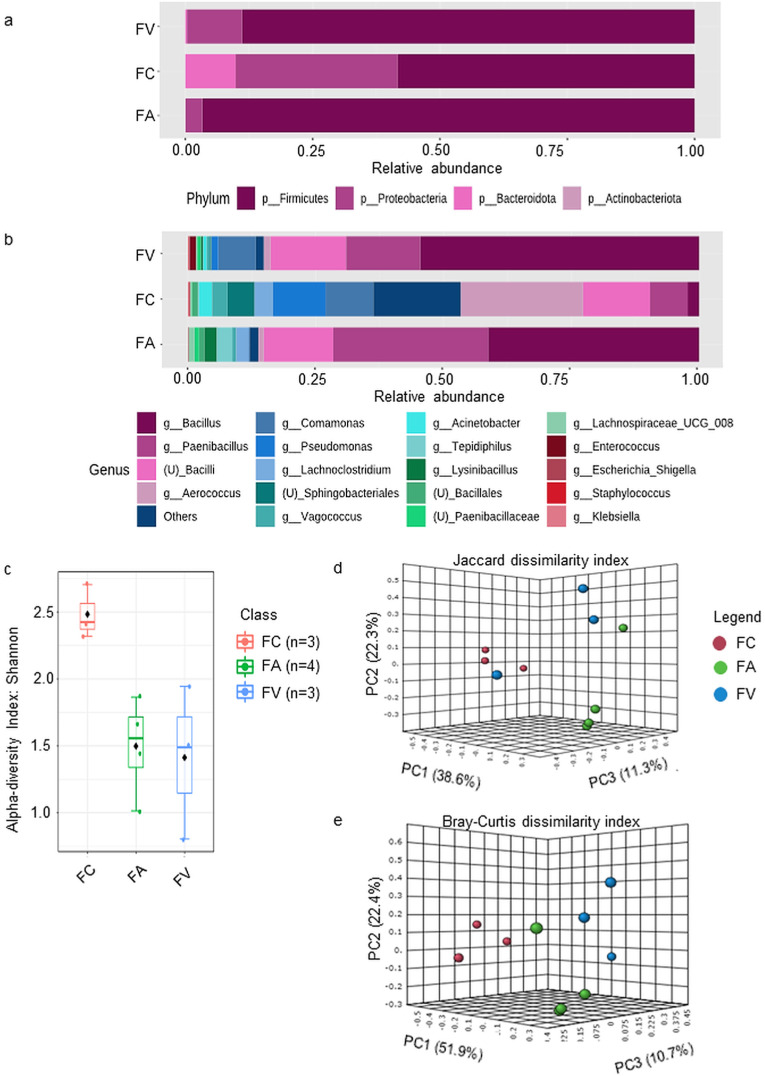

A total of 85 bacterial species were recovered from the three groups of microwave pre-treated HCW. Firmicutes phyla predominated in all three groups of HCW samples, with FA recording the highest (96.6%), followed by FV (88.8%) and FC (58.3%) (Fig. 1 a). At the genus level (Fig. 1b), Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and unclassified bacilli genera were prevalent in FV (54.5%, 14.6%, and 14.8%, respectively) and FA (41.3%, 30.3%, and 13.6%, respectively) samples, accounting for 85% of total bacteria abundance. The FC sample recorded a considerably different genus composition than FV and FA, with a high prevalence of Aerococcus (23.9%), Pseudomonas (10.3%), Comamonas (9.4%), unclassified bacilli (13.2%), and minor genera that binned as Others (17%).

Fig. 1.

Profiling of bacteria communities identified from microwave-based treated HCW samples collected from three different waste operators. The relative abundances of bacteria in merged samples were depicted at the (a) phylum; and (b) genus levels. Others, includes genera of <5 median counts (c) The alpha-diversity analysis using the Shannon diversity index at the genus level reveals samples from FC have the highest population diversity within the samples at the genus level (p-value = 0.048642); The beta-diversity PCoA 3D plots were constructed using (d) Jaccard; and (e) Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metrics, showing a clear separation between groups with a p-value <0.006.

The alpha-diversity analysis using the Shannon diversity index (Fig. 1c) demonstrated significant species richness and evenness within each sample (p-value = 0.048642, [ANOVA] F-value = 4.8025), with FC samples having the highest number of ASVs, followed by FA and FV samples. Next, the beta-diversity using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) indicated significant differences in bacterial composition at the genus level across three sets of HCW samples, as evidenced by Jaccard (F-value: 3.8383; R2: 0.52305; p-value <0.006) (Fig. 1d) and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity indices (F-value: 6.1216; R2: 0.63624; p-value <0.006) (Fig. 1e). The Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) 3D plots revealed that FA, FV, and FC clustered apart from each other, with the FC sample being distantly related to FA and FV. Additional information on taxonomic abundance at the class, order, family, and species levels can be found in the supplementary data sections (Table S1, Fig. S1).

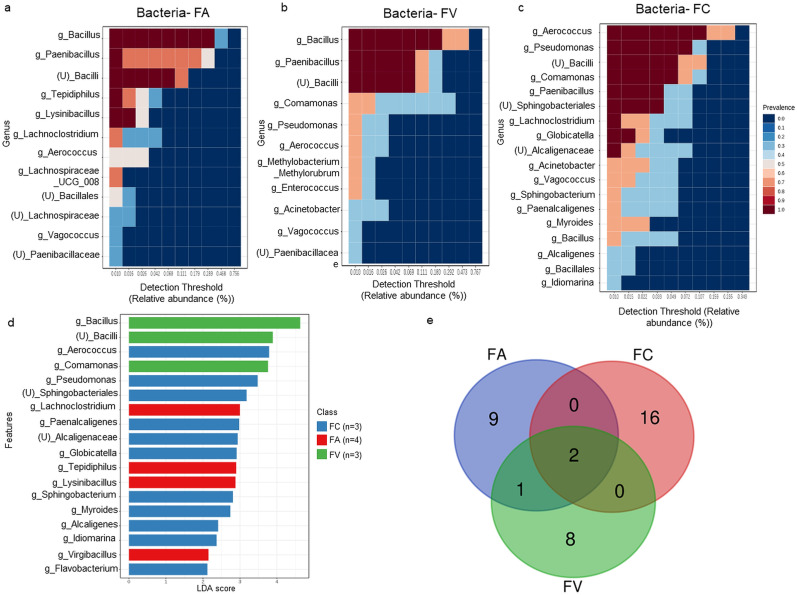

3.2. Comparison of bacterial features between three groups of HCW samples

The core microbiota in FA and FV samples were constituted by Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and unclassified Bacilli genera (prevalence = 1.0), closely matching the dominant taxa from taxonomic classification (Fig. 2 a and b). Meanwhile, the core microbiome in the FC sample was represented by Aerococcus, Pseudomonas, unclassified Bacilli, Comamonas, Paenibacillus, unclassified Sphingobacteriales, Lachnoclostridium, Globicatella, and unclassified Alcaligenaceae genera (prevalence = 1.0) (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of bacterial populations from pre-treated HCW samples collected from three different waste operators. The heatmaps illustrated the identified core microbiota in the samples (a) FA; (b) FV; and (c) FC; (d) The barplot depicted the significant bacterial taxa across three groups of HCW using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe). The red, blue, and green boxplots represented HCW from FA, FC, and FV, respectively; (e) The Venn diagram showed the comparison of core microbiota between three groups of samples. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis displayed the significant bacterial relative abundance across three groups of HCW samples. Tepidiphilus, Lachnoclostridium, Virgibacillus, and Lysinibacillus were found to be significant in the FA sample, while Bacillus, Comamonas, and unclassified Bacilli genera were significant in the FV sample (Fig. 2d). The FC sample constituted 11 significant bacterial taxa out of 18, including Aerococcus, Pseudomonas, Paenalcaligenes, Myroides, Flavobacterium, Alcaligenes, and unclassified Alcaligenaceae genera. Complete LEfSe analysis data for the bacterial population in HCW can be found in Table S2. A Venn diagram was used to compare the core microbiota of three groups (Fig. 2e). Two common bacteria, Paenibacillus, and unclassified Bacilli genera were identified in all three groups of samples, while Bacillus genera were shared between FA and FV samples. The complete Venn diagram result is available in the supplementary section (Table S3).

3.3. Fungal community profiling of HCW samples

3.3.1. Overview of fungal composition and diversity

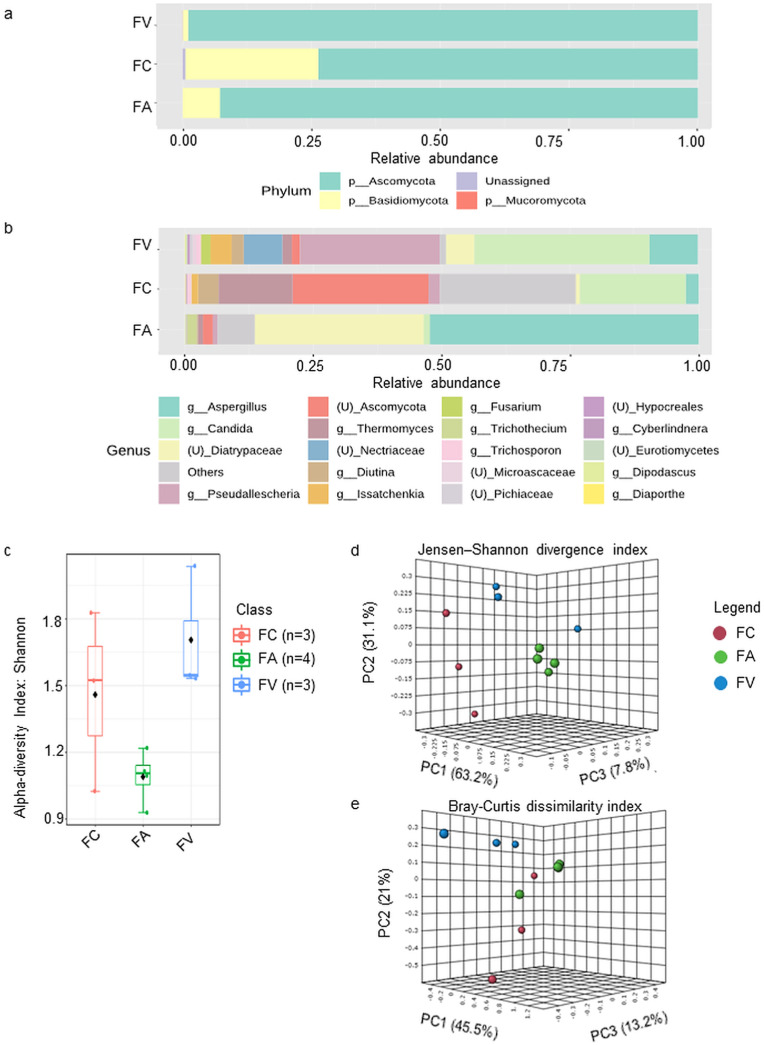

A total of 36 fungi species were identified, and the fungal composition revealed that Ascomycota was found to predominate in all three sets of HCW samples, accounting for 98.9%, 73.7%, and 92.8% of the FV, FA, and FA samples, respectively, while Basidiomycota made up another 25.8% of the bacterial composition in the FC sample (Fig. 3 a). The top 20 genera indicated that the FV sample had a high prevalence of Candida (34.1%) and Pseudallescheria (27.3%) genera, whereas the FA sample had a high abundance of Aspergillus (52.3%) and unclassified Diatrypaceae (32.9%). Meanwhile, FC samples revealed a few genera, such as unclassified Ascomycota (26.5%), Candida (20.6%), Thermomyces (14.4%), and minor genera that were grouped with Others (26.4%) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Fungi communities identified from microwave-based treated HCW samples collected from three different waste operators. The relative abundances of fungi in merged samples were depicted at the (a) phylum level; and (b) genus level. Others, includes genera <4 median counts. (c) The alpha-diversity analysis using the Shannon diversity index at the genus level reveals samples from FC have the highest population diversity within the samples at the genus level (p-value = 0.058); The beta-diversity PCoA 3D plots were constructed using (d) Jensen–Shannon divergence; and (e) Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metrics, showing a clear separation between groups with a p-value <0.002.

The alpha-diversity analysis by the Shannon diversity index (Fig. 3c) revealed that FV contained the most ASVs at the genus level, followed by FC and FA, demonstrating a significant difference in terms of fungal species richness and evenness within each HCW sample (p-value = 0.04459, [ANOVA] F-value = 5.0114). The beta-diversity analysis by the PERMANOVA method showed significant variation between three sets of HCW samples, as evidenced by Jensen–Shannon divergence (F-value: 12.022; R2: 0.77452; p-value <0.002) (Fig. 3d) and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metrics (F-value: 3.9442; R2: 0.52984; p-value <0.002) (Fig. 3e).

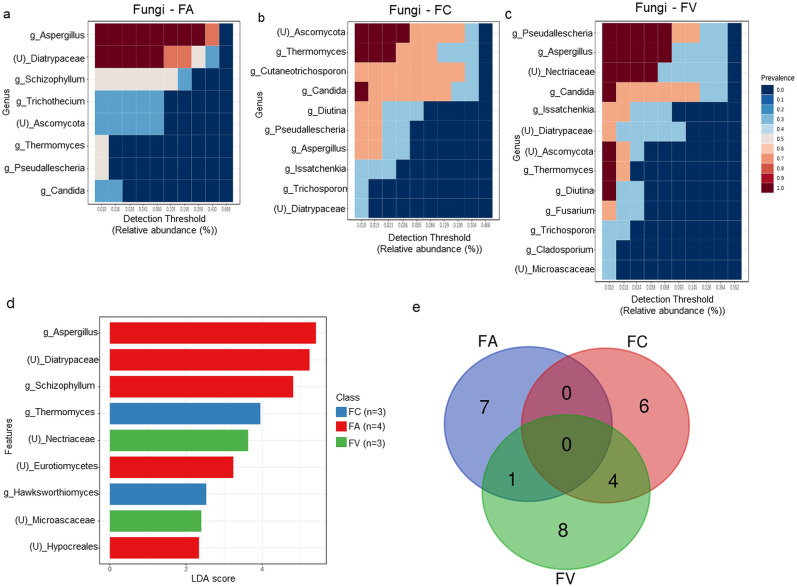

3.3.2. Comparison of fungal features between three groups of HCW samples

The heatmaps illustrated the distribution of the core mycobiota identified in each HCW sample at the genus level. Aspergillus and unclassified Diatrypaceae (prevalence = 1.0) made up the core mycobiota in the FA sample (Fig. 4 a), whereas the FC sample was dominated by unclassified Ascomycota, Thermomyces, and Candida genera (prevalence = 1.0), followed by Cutaneotrichosporon, Diutina, Pseudallescheria, and Aspergillus genera (prevalence = 0.7) (Fig. 4b). On the other hand, the FV sample reported a distinct core fungal composition represented by the genera Pseudallescheria, Aspergillus, unclassified Nectriaceae, Candida, unclassified Ascomycota, Thermomyces, and Diutina (prevalence = 1.0) (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Comparative analysis of fungal populations from pre-treated HCW samples collected from three different waste operators. The heatmaps illustrated the identified core mycobiota in samples (a) FA; (b) FC; and (c) FV; (d) The barplot depicted the distinctive fungal taxa across three groups of HCW using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe). The red, blue, and green boxplots indicated medical waste from FA, FC, and FV, respectively; (e) The Venn diagram showed the comparison of core mycobiota between the three groups of samples. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The distinctive fungal features between three sets of HCW samples were highlighted in LEfSe analysis, with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) corrected p-value <0.05 deemed significant (Table S5). LEfSe detected 9 fungal genera showing a statistically significant difference in HCW samples with LDA scores greater than 4. In detail, the FV sample comprised two significant fungal genera, which are unclassified Nectriaceae and unclassified Microascaceae. Aspergillus, unclassified Diatrypaceae, Schizophylum, and Hypocreales were the four significant fungal genera found in the FA sample, while Thermomyces and Hawksworthiomyces genera belonged to the FC sample. In addition to the comparison of the core microbiome and diversity analysis, no fungal taxa were consistently present in all three sets of samples (Fig. 4e, Table S6), for which the distribution of taxa varies in terms of their prevalence, and thus no fungal taxa were determined to represent the HCW sample as a whole.

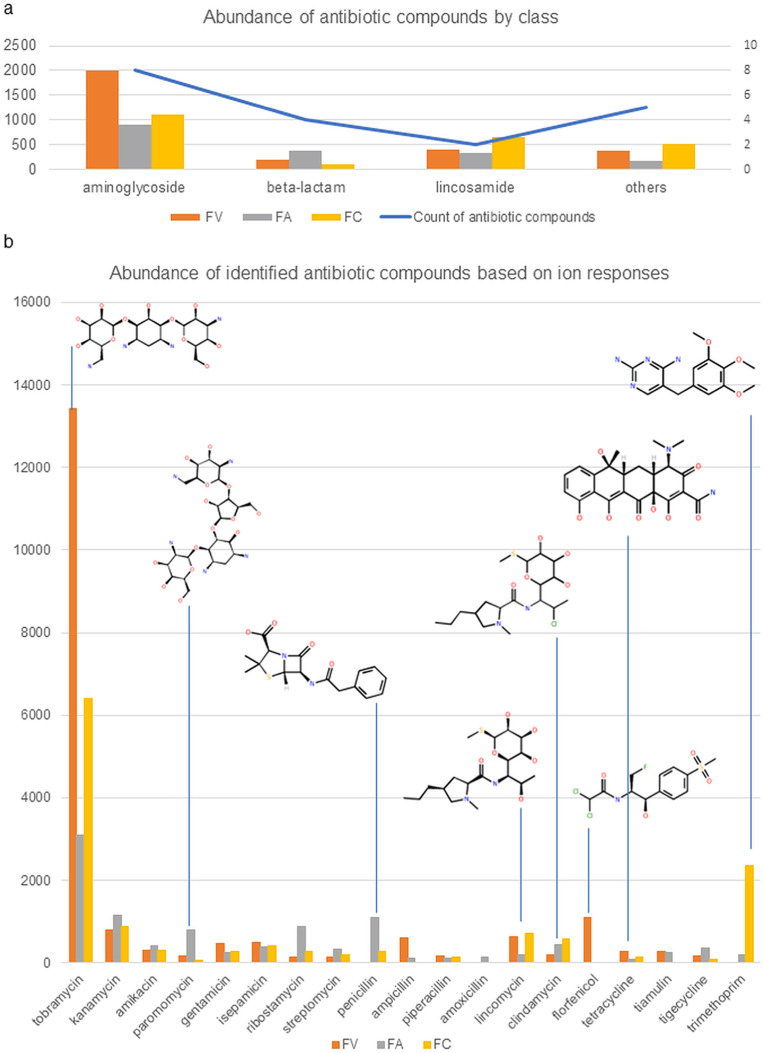

3.4. Antibiotic compounds in HCW samples based on UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis

The antibiotic profiles in the HCW samples were screened using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOF-MS) based on the mass error. The analysis confirmed the presence of 19 good matches of identified compounds with different ion response intensities. Eight of the 19 antibiotics are aminoglycosides, four are beta-lactams, two are lincosamides, and the rest are from various classes of antibiotics (Table 2 ). Aminoglycosides, represented by tobramycin and kanamycin, were identified as the most prevalent antibiotic class in all three sets of HCW samples, followed by lincosamides, represented by lincomycin and clindamycin (Fig. 5 ). Other antibiotic compounds identified in two sets of HCW samples were penicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, florfenicol, tiamulin, and trimethoprim (Fig. 5b). Overall, antibiotic residues were discovered to be higher in FV and FC samples than in FA samples (Fig. 5a). The raw data for all analytes detected during UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis are provided in Tables S7–S12.

Table 2.

Average abundance of antibiotics identified in HCW based on UPLC-QTOF-MS ion responses.

| Antibiotic class | Antibiotics | FV | FA | FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aminoglycoside | tobramycin | 13,441 | 3106.67 | 6412.21 |

| kanamycin | 789.75 | 1150.165 | 869.665 | |

| Amikacin | 318.75 | 412 | 308.25 | |

| paromomycin | 184.125 | 789.235 | 53 | |

| gentamicin | 474.5 | 248.15 | 270.165 | |

| isepamicin | 494.75 | 377.125 | 419.75 | |

| ribostamycin | 154 | 871.5 | 272.25 | |

| streptomycin | 152.835 | 343.275 | 191.75 | |

| beta-lactam | penicillin | 0 | 1091.165 | 280.5 |

| ampicillin | 621.5 | 126 | 0 | |

| piperacillin | 163 | 113.25 | 148.5 | |

| amoxicillin | 0 | 153 | 0 | |

| lincosamide | lincomycin | 628.25 | 202.25 | 708 |

| clindamycin | 189.5 | 445.375 | 580.5 | |

| Others | florfenicol | 1102.5 | 0 | 0 |

| tetracycline | 289 | 102.5 | 141.5 | |

| Tiamulin | 287.085 | 252.665 | 0 | |

| tigecycline | 177.25 | 354.3 | 77.5 | |

| trimethoprim | 0 | 200 | 2346.5 |

Fig. 5.

Abundance of antibiotic compounds identified in three groups of HCW samples based on UPLC-QTOF-MS ion responses. Bar plots illustrated (a) the average abundance and count of identified antibiotic compounds by class; and (b) the total abundance of identified antibiotic compounds in three groups of samples. Each horizontal bar was colored orange, grey, or yellow to represent samples FV, FA, and FC, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

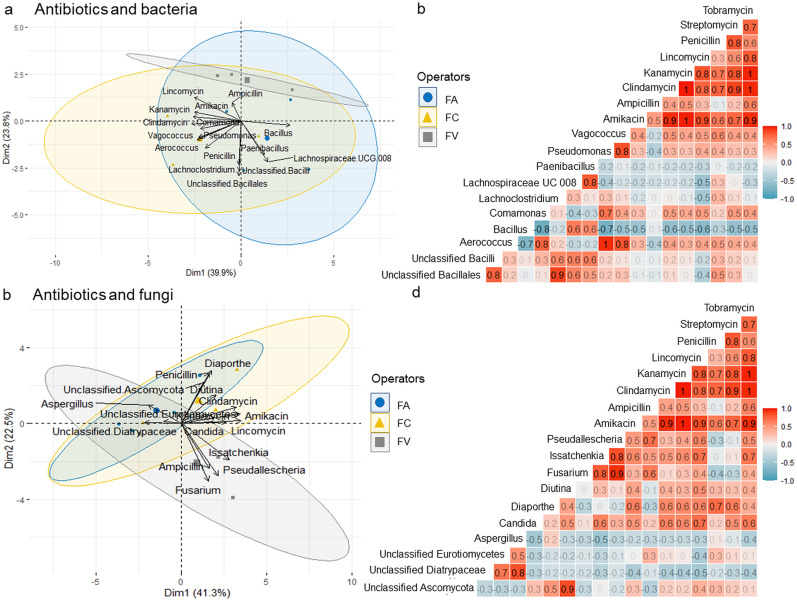

3.5. Correlation between bacterial and fungal communities and antibiotics in HCW

PCA analysis was performed to examine the association between antibiotic compounds and the microbial population in each set of HCW samples. Fig. 6 a depicts a PCA analysis of antibiotics and bacteria at the genus level. The data variance was described by two dimensions (Dim) with overlap observed among the three groups. Dim 1 (39.9%) and Dim 2 (23.8%) exhibited negative loadings with antibiotic compounds and bacterial population, respectively. The antibiotics were discovered to cluster together and closely linked with one another. The PCA plot demonstrated a positive correlation between the majority of antibiotics and the genus Comamonas, Vagococcus, Aerococcus, and Pseudomonas (Fig. 6a). In contrast, Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and Lachnospiraceae UCG 008 were adversely linked with most of the antibiotics. Meanwhile, the antibiotics had little association with unclassified Bacillales, unclassified Bacilli, and Lachnoclostridium. The extent of correlation between bacteria and antibiotics was visualized by the correlation matrix heatmap (Fig. 6b). We found that antibiotics had a moderate to weak negative effect on most of the bacteria genera, except for Vagococcus, Pseudomonas, Comamonas, and Aerococcus. It is worth noting that penicillin has low positive influences on bacteria survival, other than Bacillus and Paenibacillus.

Fig. 6.

Multivariate statistical analysis of the top eight antibiotics with bacteria (n = 10) and fungi genus (n = 10) isolated from microwave pre-treated HCW samples. Principal component analysis (PCA) biplots of antibiotics with (a) bacteria; (c) fungi illustrated the PCA scores of the explanatory variables as vectors (lines in black) and points [FA (blue circles), FV (yellow triangle), FC (grey square)] on dimension (Dim) 1 (x-axis) and 2 (y-axis). Points on the same side can be interpreted as similar profile responses. The magnitude of vectors (lines) shows the strength of the contribution to each PC. Vectors pointing in the same direction indicate positively correlated variables, while the vectors pointing in opposite directions indicate a negative correlation. Vectors at approximately right angles indicate low or no correlation. The colored 95% confidence ellipses show the observations grouped by operators. Correlation matrix illustrating the relationship between antibiotics and microbial genera, (b) bacteria; (d) fungi at p < 0.05 significant level. A positive correlation is shown by red while a negative correlation was denoted by blue. The Phi correlation coefficient is represented by the color strength and the numerical value. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Likewise, Fig. 6c showed the PCA analysis of antibiotics and fungi at the genus level exhibited positive loadings on Dim 1 (41.3%), with no obvious separation between the three groups of HCW samples. The majority of the fungi were favorably associated with the antibiotics, except for unclassified Eurotiomycetes, unclassified Diatrypaceae, and Aspergillus which were found to be adversely linked with all antibiotics. The correlation matrix heatmap revealed a moderate positive link between antibiotics and most of the fungal genera, although Aspergillus, unclassified Eurotiomycetes, unclassified Diatrypaceae, and unclassified Ascomycota showed a weak to no association with antibiotics (Fig. 6d). In contrary to bacteria, penicillin has little impact on fungi population, with the exception of Diaporthe, which has a moderately positive connection to penicillin.

On the other hand, the significance of correlation in bacteria and fungi for coefficients greater than 0.5 was examined. At a significance threshold of 0.05, Pearson's correlation coefficient was employed to test the significance of the correlation between the microbial and antibiotics discovered in three groups of samples. While most of the antibiotics had non-significance effect on most bacteria, this investigation found that lincomycin and tobramycin have significant positive influences on fungal survival (p < 0.05), including Issatchenkia, and candida genera (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficient of microbial and antibiotics with a correlation greater than 0.5.

| Microbial group | Genus | Antibiotics | Pearson (p < 0.05) | Correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bacteria | Vagococcus | penicillin | 0.10 | 0.6 |

| 2 | Bacillus | clindamycin | 0.10 | −0.6 | |

| lincomycin | 0.05a | −0.6 | |||

| 3 | Fungi | Pseudallescheria | ampicillin | 0.02 | 0.7 |

| lincomycin | 0.07 | 0.6 | |||

| 4 | Issatchenkia | amikacin | 0.08 | 0.6 | |

| kanamycin | 0.10 | 0.6 | |||

| kincomycin | 0.03a | 0.7 | |||

| tobramycin | 0.03a | 0.7 | |||

| 5 | Fusarium | penicillin | 0.30 | 0.6 | |

| 6 | Diaporthe | amikacin | 0.06 | 0.6 | |

| clindamycin | 0.08 | 0.6 | |||

| kanamycin | 0.08 | 0.6 | |||

| lincomycin | 0.07 | 0.6 | |||

| penicillin | 0.02a | 0.7 | |||

| streptomycin | 0.05a | 0.6 | |||

| 7 | Candida | clindamycin | 0.07 | 0.6 | |

| kanamycin | 0.09 | 0.6 | |||

| lincomycin | 0.02a | 0.7 | |||

| tobramycin | 0.04a | 0.6 |

Indicates significant.

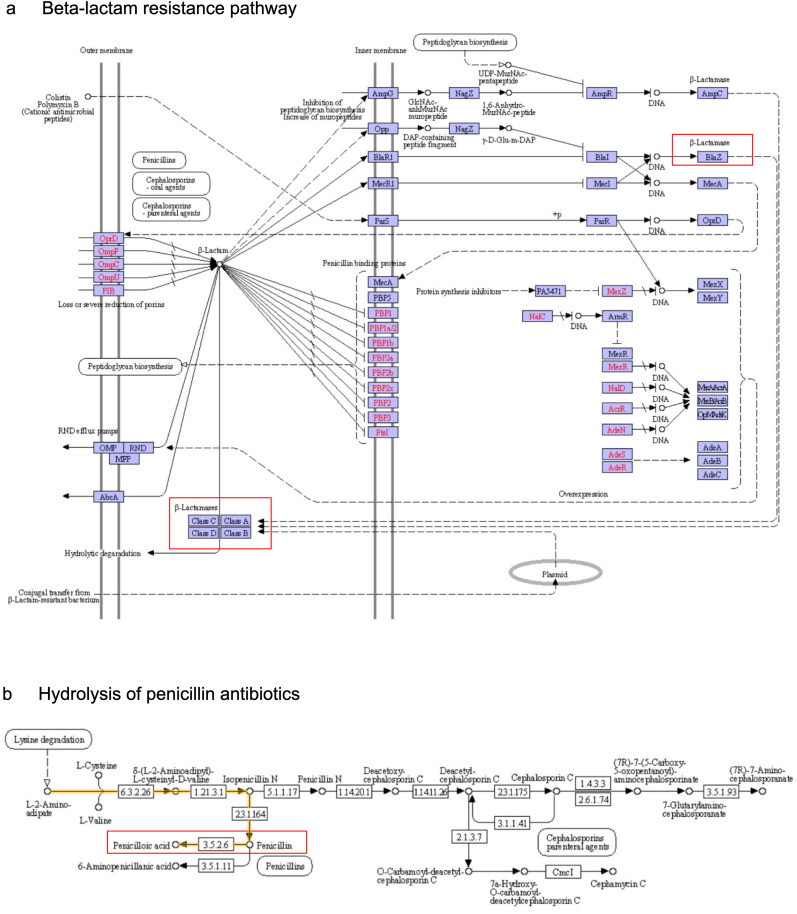

3.6. ARGs prediction and functional genes annotation using bioinformatics tools

The correlation between microbial community and antibiotics was further validated by characterizing the ARGs in the HCW samples. Here, we found the presence of potential ARGs encoding for TEM-1 beta-lactamase in the samples FC1 and FV3 samples, which confer resistance to the beta-lactam antibiotics (Table 4 ). In addition, we annotated the respective sequences to the KEGG database and revealed the presence of blaZ and Class A beta-lactamase encoding genes in the beta-lactam resistance pathway (Fig. 7 a). Likewise, the gene annotation result also indicated the presence of penP gene encoding for the beta-lactams enzyme group (EC 3.5.2.6) was associated with the hydrolysis of penicillin antibiotics into penicilloic acid (Fig. 7b).

Table 4.

Presence of ARGs predicted using ARGs-OAP and expressed in 16 S rRNA gene copy number.

| Antibiotic |

Gene | 16 S rRNA gene copy number | Databases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Subtype | |||

| Beta-lactam | TEM-1 | gi|1,031,680,777| gb|ANG36213.1| |

FC1 = 3.52E-05 | SARG (Yin et al., 2018) |

| gi|1,031,654,576| gb|ANG23785.1| |

FV3 = 0.00019727 | |||

| penP | YP006711715.1 | Present | KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2016) | |

Fig. 7.

Gene annotation of HCW samples against the KEGG database performed using KAAS revealed the existence of (a) blaZ and class A beta-lactamase encoded genes in the beta-lactam resistance pathway; and (b) involvement of enzyme group EC 3.5.2.6 in hydrolyzing penicillin antibiotics in samples FC1 and FV3, which contribute to resistance to penicillin. The protein groups coded in green show the involvement of ARGs identified from HCW samples. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

The HCW represents a potential risk of causing infection during handling and disposal, hence requires proper treatment before final disposal to prevent the release of clinically isolated pathogens and toxic pollutants into the surrounding environment. Previous studies using conventional culture methods revealed that solid HCW from different units in healthcare facilities contained pathogenic bacteria (Hossain et al., 2013) and fungi (Noman et al., 2016), but confer several limitations. Mainly, the use of selective culture media leads to an underestimation of microbial compositions. To compensate this, the development of long-read NGS with targeted genetic markers allows for rapid and accurate microbial communities identification without bias (Sabat et al., 2017). Furthermore, there was relatively limited data documenting research on microwave technology for HCW treatment using the high-throughput NGS method in Malaysia, especially during the pandemic of COVID-19.

HCW is defined as wastes generated by healthcare facilities, particularly pathogenic waste, clinical waste, and quarantined materials coded Scheduled Waste (SW) 404, which must be carefully disposed by Department of Environment (DOE)-licensed waste operators following the Environmental Quality (Scheduled Wastes) Regulations 2005 and the Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia standard operating procedure (Agamuthu and Barasarathi, 2021; Yi and Jusoh, 2021). FA, FV, and FC are the few licensed waste operators in Malaysia providing Healthcare Waste Management services (HWMS) for the Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH), including collection, transportation, treatment, and disposal of COVID-19 wastes. FA managed HCW generated in private hospitals and clinics, while FV and FC were responsible for HCW from government healthcare facilities. FA, FV, and FC waste operators are in charge of HCW management in Peninsular Malaysia's east coast (Negeri Sembilan, Kelantan, Pahang, and Terengganu), south (Melaka, and Johor), and west coast (Selangor, Perlis, Kedah, Pulau Pinang, and Perak), respectively. In the present study, FA and FV microwave pre-treated wastes were revealed to have comparable bacteria compositions dominated by Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and unclassified Bacilli. Conversely, the FC sample had a distinct bacterial composition dominated by the genera Aerococcus, Pseudomonas, Comamonas, unclassified bacilli, and other minor bacteria. Bacterial abundance from the three groups showed specific distribution patterns, regardless of the sample collected from different facilities. Despite the same bacteria identified in FA and FV samples, the alpha- and beta-diversity analysis indicated significant differences in the bacterial population at the genus level across the three groups of samples. The bacterial species recovered from samples revealed decreasing species ASVs in FC, FA, and FV, which may be ascribed to the persistence of different types of microorganisms in the hospital environment in relation to the number of patients with associated infections and degree of human activity, as evidenced by W. Zhang et al. (2021).

HCW was discovered to harbor environmental and clinically relevant microorganisms capable of causing disease transmission (Padmanabhan and Barik, 2019). Likewise, the LEfSe analysis revealed a wide range of significant clinically relevant bacteria in this study, particularly Aerococcus (Mohan et al., 2017), Pseudomonas (de Bentzmann and Plésiat, 2011), Comamonas (Zhou et al., 2018), Paenalcaligenes (Olowo-okere et al., 2020), Globicatella (Miller et al., 2017), Lysinibacillus (Morioka et al., 2022; Wenzler et al., 2015), Sphingobacterium (Azarfar et al., 2020; Barahona and Slim, 2015), Myroides (Kurt et al., 2022), and Alcaligenes (Lang et al., 2022). Most of the Bacillus species are not pathogens, with the exception of B. circulans and B. oleronius, which reported to cause meningitis and Rosacea, respectively (Kim, 2020; Russo et al., 2021).

The core microbiome prevalence and LEfSe result revealed a bacterial frequency trend, with FC gaining more clinically relevant pathogens than FA and FV samples. According to Klassert et al. (2021), bacterial colonization in the hospital environment is associated with patient occupancy and can serve as a disease source. Yet, this trend also suggests that these microbiotas may be involved in host-microbe systems and pose underlying risks in HCW related to various diseases and environmental issues. Despite the bacterial diversity in the HCW, Bacillus and Paenibacillus were present in all three groups of samples as shown in the Venn diagram. Bacillus and Paenibacillus are widespread in the environment and have been increasingly implicated in various human diseases (Celandroni et al., 2016; Sáez-Nieto et al., 2017). However, little is known about their species identification, thus their pathogenicity on humans remains limited.

Multiple studies have been undertaken to examine microbial inactivation using microwave treatment in contaminated solid HCW but none have documented the complete microbial population after microwave treated HCW (Banana et al., 2013; Kollu et al., 2022). Our findings were partially consistent to Mahdi & Gomes (2019) and Mawioo et al. (2017) whereby microorganisms such as Bacillus, Clostridium and Enterococcus faecalis were still discovered in HCW after microwave treatment. It can be deduced that bacterial inactivation may occur with respect to microwave powers and treatment time, but microwave treatment may not completely inactivate the microorganisms (Mahdi and Gomes, 2019). Meanwhile, survival of microorganisms was dependent on the susceptibility of the cell wall to microwave irradiation. The presence of a thick peptidoglycan layer in gram-positive bacteria protects them against radiation exposure, resulting in greater resistance to microwave treatment (Yahya et al., 2021).

In terms of fungal abundance, the Ascomycota phylum was found to dominate in three groups of samples. However, no common fungus was found in any of the three groups of samples, indicating that fungi colonization on the surface of HCW samples was independent of hospital environments and waste sources. The alpha- and beta-diversity profiles revealed significant variation in all three groups, with FV and FA having the highest and lowest ASV counts at the genus level, respectively. Among the nine significant fungi indicated by the LEfSe analysis, Aspergillus was recognized as a clinically significant pathogen causing Aspergillosis in humans (Diba et al., 2019; Paulussen et al., 2017). Other pathogenic fungal taxa identified as core mycobiota in FC and FV samples were genera Pseudallescheria (Luplertlop, 2018), Candida (Turner and Butler, 2014), and Diutina (Chen et al., 2021). The diversification of fungal in the HCW may be linked with mycological contamination in the air and on the surface, which has been frequently observed in hospital settings and might contribute to fungal infections (Jackson and Chiller, 2018; Jalili et al., 2021). Our results contradicted the findings of Kollu et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2020), who reported that microwave radiation can effectively destroy fungi as demonstrated by microbial log reduction. This may be due to the component of the cell wall (chitin) in fungi, which provides additional support and makes them more resistant to radiation than bacteria, which are less likely to be killed by microwave radiation (Wu and Yao, 2010).

As a measure of infection control, multi-drug and antibiotic regimens are routinely used in the treatment of serious infections. The UPLC-QTOF-MS metabolomic analysis uncovered the presence of antibiotic residues that had not been eliminated from microwave pre-treated HCW. Aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, and lincosamides antibiotics found in the HCW are commonly used to treat serious bacterial infections (Germovsek et al., 2017; Maguigan et al., 2021; Spížek and Řezanka, 2017). In all circumstances, the presence of antibiotic compounds can influence the microbial community in HCW. Antibiotic-susceptible microorganisms will be eradicated, but antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) will survive and proliferate regardless of the presence of antibiotics. It is worth noting that Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecium, and Enterococcus faecalis, well-known ARBs that cause human infections and fatalities, were found in modest quantities. Of these, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium has been listed as a priority pathogen by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the urge for new antibiotics for treatment (World Health Organization, 2017). Despite the extensive antibiotic residues discovered in the HCW, little is known about the prevalence of antibiotics in the environment due to a lack of literature focusing on antibiotic spatial distribution across Malaysia.

The PCA plot described the variation in the bacterial and fungal composition related to the antibiotics (63.7% and 63.8%, respectively), with antibiotic prevalence being the driving factor influencing the distribution of the microbial composition. The overlapping of three sets of bacteria and fungi samples was found to have similar Dim scores in PCA analysis, indicating comparable variance in both sets. Most antibiotics are shown to be resistant to Aerococcus, Comamonas, Pseudomonas, and Vagococcus (Matsuo et al., 2021a), which have been reported to cause infections in humans, whereas Bacillus and Paenibacillus are susceptible to all the antibiotics. Despite that antibiotics have no substantial effect on these bacteria, studies have shown that Aerococcus (Rasmussen, 2016), Comamonas (Moser et al., 2021), Vagococcus (Racero et al., 2021), and Pseudomonas (Butiuc-Keul et al., 2021) have developed antibiotic resistance. Correlation analysis predicted that they had low penicillin and ampicillin sensitivity while being resistant to other antibiotics. Thus, we anticipate that these pathogenic bacteria will be able to survive when exposed to drugs to which they are resistant. The AMR may be attributed to intrinsic resistance or ARG acquisition from other bacteria, as clinical isolates have a variety of ARB (Hailemariam et al., 2021). On the other hand, antibiotics are found to be resistant to most identified fungi, particularly tobramycin and lincomycin. Tobramycin and lincomycin are well known antibiotics used to treat bacterial infections in humans, but there is minimal evidence that they are efficient in inhibiting the growth of fungi. Even though antibiotics have some inhibitory effects against fungi, antibacterial agents were still deemed inferior to antifungal agents (Kawakami et al., 2015). Here, it is noteworthy that Candida sp. Clinical isolates, such as C. albicans and C. tropicalis, are multidrug-resistant, thus resistant to all the antibiotics as illustrated in the heatmap (Arastehfar et al., 2020). Although the multivariate analysis demonstrated a link between antibiotics and microorganisms, it may not completely reveal the pattern of antibiotic resistance in clinical pathogens as antibiotic susceptibility differs between different species.

The presence of bacteria and antibiotics also suggests that those bacteria may harbor linked ARGs (R.-M. Zhang et al., 2021). The screening of ARGs in HCW samples discovered the prevalence of bla TEM-1 in FC and FV samples. Bla TEM is a well known beta-lactam resistance determinant that has been widely reported in clinical isolates of gram-negative bacteria (Domínguez-Pérez et al., 2018; Haider et al., 2022; Katiyar et al., 2020). The bla TEM-1 gene encodes TEM-1 class A beta-lactamase that confers resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin and first-generation cephalosporins by hydrolyzing the beta-lactam ring of antibiotics (Salverda et al., 2010). Meanwhile, the overexpression of bla TEM-1 can lead to resistance to other antibiotics such as clavulanate and sulbactam (K. Zhou et al., 2019). Furthermore, plasmid and transposon-mediated TEM-1 beta-lactamase may easily transfer resistance determinants between bacteria via mobile elements like plasmids and transposons (Singh et al., 2018). Our finding was further supported by the existence of blaZ and class A beta-lactamase encoded genes (bla TEM and penP) in the KEGG beta-lactam resistance pathway, and penP encoded beta-lactamase (EC 3.5.2.6) that is involved in the hydrolysis of penicillin into inactive penicilloic acid, causing bacteria to be resistant to penicillin (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2022). As such, we believe that microwave has a limited ability to completely remove ARB and antibiotics from HCW, which may lead to environmental pollution and the development of new antibiotic-resistant bacteria through ARG dissemination and evolution (Larsson and Flach, 2022). Despite the diverse clinically relevant bacteria identified in the HCW, only one ARG was detected in two HCW samples. Given that the parameters for ARGs annotation against the SARG v2.0 database were 80% similarity and 70% alignment coverage (Yin et al., 2018), we extrapolate that the low abundance of ARBs in amplicon data may have resulted in undetected ARGs owing to the inadequate read coverage in the HCW read sequences.

Microwave technology is shown to be effective in destroying pathogens in HCW when applied in a properly designed microwave system under strictly regulated conditions (Wang et al., 2020, Zimmermann, 2018). The microwave efficiency can be influenced by the radiation exposure period, power per waste mass unit, and moisture content in HCW (Banana et al., 2013). Coupled with the presence of clinically significant microorganisms and antibiotic compounds in HCW, these findings suggested that current microwave techniques in Malaysia had limited effectiveness in eliminating microorganisms, resulting in the revival of pathogenic bacteria during the storage period in the presence of moisture. As no data regarding the HCW sample before microwave treatment and the parameters used in microwave treatment are unclear, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact radiation power and duration to achieve acceptable inactivation levels. According to a recent review by Kenny and Priyadarshini (2021), microwaving is only suitable for small-scale HCW treatment and should not be considered as an alternative technology to incineration due to the possibility of bacteria re-growth. Thus, incineration should be adopted as the best available technique for HCW treatment with an optimized control strategy.

The overall evaluation showed that pathogenic bacteria and ARGs are closely linked with the high health risk of humans and the environment through the selection of ARGs in the human body and the environmental microbiome (Ben et al., 2019). However, no standard was established for evaluating the health risks of antibiotic residues in HCW, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. In addition, the severely limited available data reflected the knowledge and evidence gaps in characterizing the risks of antibiotic residues in the environment. The main future research needs to enable better assessment of antibiotic residues in the environment and their distribution across Malaysia. Hence, this study might lay the groundwork for further research into antibiotic distribution in Malaysia and drive research into potential solutions for eliminating them.

Our work has several limitations owing to the unclassified taxonomy at the species level, which leads to a limited understanding of the pathogenicity of characterized microbial and the impact of these microorganisms on human beings and the environment. Moreover, the large quantity of microbial identified in HCW made the correlation analysis between microorganisms and antibiotics more challenging, as only limited microbes can be selected for comparison due to limited resources in plotting the results. Also, the present study only targeted the DNA-based method that described the bacterial and fungal components of the waste, which limits a detailed identification of viral components based on RNAs. Lastly, due to the lack of a comprehensive fungal database for ITS analysis, we were unable to perform a depth fungal study, and hence the genotype and antimicrobial resistance properties in identified fungi could not be thoroughly examined.

5. Conclusion

The current study discovered that the three groups of microwave pre-treated HCW contained a large relative abundance of microorganisms, indicating that current microwave technology has a negligible effect on microbial reduction. Bacillus and Paenibacillus genera were discovered as common shared bacteria across all three groups of HCW. Meanwhile, the occurrence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in HCW, such as Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecium, and Enterococcus faecalis serves as a reservoir for pathogen transmission during waste handling and disposal. The positive correlation between clinically relevant microorganisms and antibiotics revealed the possible antibiotic resistance patterns in HCW samples. Furthermore, bacteria communities were found to have bla TEM-1 and penP genes that are involved with the production of class A beta-lactamase in beta-lactam resistance pathways. The coexistence of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in HCW showed the possibility of environmental contamination and the spread of ARBs bacteria if improperly treated HCW was disposed to landfills. Hence, Malaysia necessary to revise the current policies and guidelines to improve HCW disposal with existing resources while maintaining sustainable waste management.

Author statement

SWS: Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. SMM: Investigation, Validation. NAS: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MFFA: Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. HFA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision

Data Avaibility

The sequencing data of medical waste bacterial populations was accessible in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database under the BioProject accession number PRJNA822103, and the BioSample accession number was deposited as SAMN27177688 to SAMN27177697 with Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accessions from SRR18585539 to SRR18585548. Whereas the sequencing data of fungal populations were deposited under BioProject accession number PRJNA822104, BioSample accession number SAMN27177701 to SAMN27177710, and SRA accessions from SRR18585560 to SRR18585569. All additional input files are provided as a supplementary file in csv.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by IIUM-UMP-UiTM Sustainable Research Collaboration Grant 2020 (SRCG); RDU200713, and Universiti Malaysia Pahang, Malaysia with Postgraduate Research Grant Scheme (PGRS); PGRS2003107. We would like to thank the Hazardous Substances Division, Department of Environment, Ministry of Environment and Water, Malaysia, for their assistance in sample collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.115139.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The data available online via NCBI

References

- Abarenkov K., Zirk A., Piirmann T., Pöhönen R., Ivanov F., Nilsson R. Henrik, Kõljalg U. UNITE Community; 2021. UNITE QIIME Release for Fungi 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd Kadir S.A.S., Yin C.-Y.Y., Rosli Sulaiman M., Chen X., El-Harbawi M. Incineration of municipal solid waste in Malaysia: salient issues, policies and waste-to-energy initiatives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013;24:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2013.03.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agamuthu P., Barasarathi J. Clinical waste management under COVID-19 scenario in Malaysia. Waste Manag. Res. 2021;39(1_Suppl. l):18–26. doi: 10.1177/0734242X20959701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agwu M. Issues and challenges of solid waste management practices in port-harcourt city, Nigeria- a behavioural perspective. Am. J. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2012;3(2):83–92. doi: 10.5251/ajsms.2012.3.2.83.92. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aljeldah M.M. Antimicrobial resistance and its spread is a global threat. Antibiotics. 2022;11(8):1082. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11081082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand U., Adelodun B., Pivato A., Suresh S., Indari O., Jakhmola S., Jha H.C., Jha P.K., Tripathi V., Di Maria F. A review of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and airborne particulates and its use for virus spreading surveillance. Environ. Res. 2021;196(December 2020) doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand U., Cabreros C., Mal J., Ballesteros F., Sillanpää M., Tripathi V., Bontempi E. Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: from transmission to control with an interdisciplinary vision. Environ. Res. 2021;197(January) doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand U., Li X., Sunita K., Lokhandwala S., Gautam P., Suresh S., Sarma H., Vellingiri B., Dey A., Bontempi E., Jiang G. vol. 203. Environmental Research; 2022. (SARS-CoV-2 and Other Pathogens in Municipal Wastewater, Landfill Leachate, and Solid Waste: A Review about Virus Surveillance, Infectivity, and Inactivation). June 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand U., Reddy B., Singh V.K., Singh A.K., Kesari K.K., Tripathi P., Kumar P., Tripathi V., Simal-Gandara J. Potential environmental and human health risks caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and emerging contaminants (ECs) from municipal solid waste (MSW) landfill. Antibiotics. 2021;10(4):374. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniadou M., Varzakas T., Tzoutzas I. Circular economy in conjunction with treatment methodologies in the biomedical and dental waste sectors. Circular Economy and Sustainability. 2021;1(2):563–592. doi: 10.1007/s43615-020-00001-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arastehfar A., Daneshnia F., Hafez A., Khodavaisy S., Najafzadeh M.-J., Charsizadeh A., Zarrinfar H., Salehi M., Shahrabadi Z.Z., Sasani E., Zomorodian K., Pan W., Hagen F., Ilkit M., Kostrzewa M., Boekhout T. Antifungal susceptibility, genotyping, resistance mechanism, and clinical profile of Candida tropicalis blood isolates. Med. Mycol. 2020;58(6):766–773. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiam JeyaSundar P.G.S., Ali A., Guo D., Zhang Z. Microorganisms for Sustainable Environment and Health. Elsevier; 2020. Waste treatment approaches for environmental sustainability; pp. 119–135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azarfar A., Bhattacharya S., Siddiqui S., Subhani N. Sphingobacterium thalpophilum bacteraemia: a case report. Internet J. Infect. Dis. 2020;18(1):1–4. doi: 10.5580/IJID.55030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banana A.A.S., Nik Norulaini N.A., Baharom J., Lailaatul Zuraida M.Y., Rafatullah M., Kadir M.O.A. Inactivation of pathogenic micro-organisms in hospital waste using a microwave. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2013;15(3):393–403. doi: 10.1007/s10163-013-0130-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barahona F., Slim J. Sphingobacterium multivorum: case report and literature review. New Microbes and New Infections. 2015;7:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterman S. Assessment of Small-Scale Incinerators; January: 2004. pp. 1–69. (Assessment of Small-Scale Incinerators for Health Care Waste). [Google Scholar]

- Ben Y., Fu C., Hu M., Liu L., Wong M.H., Zheng C. Human health risk assessment of antibiotic resistance associated with antibiotic residues in the environment: a review. Environ. Res. 2019;169:483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.11.040. July 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich N.A., Kaehler B.D., Rideout J.R., Dillon M., Bolyen E., Knight R., Huttley G.A., Gregory Caporaso J. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2's q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen E., Rideout J.R., Dillon M.R., Bokulich N.A., Abnet C.C., Al-Ghalith G.A., Alexander H., Alm E.J., Arumugam M., Asnicar F., Bai Y., Bisanz J.E., Bittinger K., Brejnrod A., Brislawn C.J., Brown C.T., Callahan B.J., Caraballo-Rodríguez A.M., Chase J., et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butiuc-Keul A., Carpa R., Podar D., Szekeres E., Muntean V., Iordache D., Farkas A. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas spp. through the urban water cycle. Curr. Microbiol. 2021;78(4):1227–1237. doi: 10.1007/s00284-021-02389-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celandroni F., Salvetti S., Gueye S.A., Mazzantini D., Lupetti A., Senesi S., Ghelardi E. Identification and pathogenic potential of clinical Bacillus and Paenibacillus isolates. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.F., Zhang W., Fan X., Hou X., Liu X.Y., Huang J.J., Kang W., Zhang G., Zhang H., Yang W.H., Li Y.X., Wang J.W., Guo D.W., Sun Z.Y., Chen Z.J., Zou L.G., Du X.F., Pan Y.H., Li B., et al. Antifungal susceptibility profiles and resistance mechanisms of clinical Diutina catenulata isolates with high MIC values. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11(October):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.739496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong J., Liu P., Zhou G., Xia J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protoc. 2020;15(3):799–821. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bentzmann S., Plésiat P. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa opportunistic pathogen and human infections. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;13(7):1655–1665. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey S., Anand U., Kumar V., Kumar S., Ghorai M., Ghosh A., Kant N., Suresh S., Bhattacharya S., Bontempi E., Bhat S.A., Dey A. Microbial strategies for degradation of microplastics generated from COVID-19 healthcare waste. Environ. Res. 2023;216(P1) doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.114438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal A., Chong J., Habib S., King I.L., Agellon L.B., Xia J. MicrobiomeAnalyst: a web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W180–W188. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diba K., Jangi F., Makhdoomi K., Moshiri N., Mansouri F. Aspergillus diversity in the environments of nosocomial infection cases at a university hospital. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2019;12(2):128–132. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Pérez R.A., De la Torre-Luna R., Ahumada-Cantillano M., Vázquez-Garcidueñas M.S., Pérez-Serrano R.M., Martínez-Martínez R.E., Guillén-Nepita A.L. Detection of the antimicrobial resistance genes blaTEM-1, cfxA, tetQ, tetM, tetW and ermC in endodontic infections of a Mexican population. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2018;15:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R.C., Haas B.J., Clemente J.C., Quince C., Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(16):2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egbenyah F., Udofia E.A., Ayivor J., Osei M.M., Tetteh J., Tetteh-Quarcoo P.B., Sampane-Donkor E. Disposal habits and microbial load of solid medical waste in sub-district healthcare facilities and households in Yilo-Krobo municipality, Ghana. PLoS One. 2021;16(12 December 2021):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekanayake A., Rajapaksha A.U., Hewawasam C., Anand U., Bontempi E., Kurwadkar S., Biswas J.K., Vithanage M. Environmental challenges of COVID-19 pandemic: resilience and sustainability – a review. Environ. Res. 2023;216(P2) doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.114496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferronato N., Torretta V. Waste mismanagement in developing countries: a review of global issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(6):1060. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16061060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germovsek E., Barker C.I., Sharland M. What do I need to know about aminoglycoside antibiotics? Archives of Disease in Childhood - Education & Practice Edition. 2017;102(2):89–93. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider M.H., McHugh T.D., Roulston K., Arruda L.B., Sadouki Z., Riaz S. Detection of carbapenemases blaOXA48-blaKPC-blaNDM-blaVIM and extended-spectrum-β-lactamase blaOXA1-blaSHV-blaTEM genes in Gram-negative bacterial isolates from ICU burns patients. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2022;21(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12941-022-00510-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailemariam M., Alemayehu T., Tadesse B., Nigussie N., Agegnehu A., Habtemariam T., Ali M., Mitiku E., Azerefegne E. Major bacterial isolate and antibiotic resistance from routine clinical samples in Southern Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99272-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantoko D., Li X., Pariatamby A., Yoshikawa K., Horttanainen M., Yan M. Challenges and practices on waste management and disposal during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;286(January) doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M., Rahman N., Balakrishnan V., Puvanesuaran V., Sarker M., Kadir M. Infectious risk assessment of unsafe handling practices and management of clinical solid waste. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2013;10(2):556–567. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10020556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-W., Lin Y.-S., Huang W.-C., Lai C.-C., Chien H.-J., Hu N.-J., Chen J.-H. Inhibition of the clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: in vitro assessment of a case-based study. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020;55(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer M., Tiwari S., Renu K., Pasha M.Y., Pandit S., Singh B., Raj N., Krothapalli S., Kwak H.J., Balasubramanian V., Jang S., Bin G.D.K., Uttpal A., Narayanasamy A., Kinoshita M., Subramaniam M.D., Nachimuthu S.K., Roy A., Valsala Gopalakrishnan A., Vellingiri B. Environmental survival of SARS-CoV-2 – a solid waste perspective. Environ. Res. 2021;197 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111015. November 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson B.R., Chiller T. Fungal Disease Outbreaks. 2018;17(12):1–18. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30443-7. (Emerging) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalili D., Dehghani M., Fadaei A., Alimohammadi M. Assessment of airborne bacterial and fungal communities in shahrekord hospitals. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2021/8864051. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal R., Pathak A., Chauhan A. Metagenomic evaluation of bacterial and fungal assemblages enriched within diffusion chambers and microbial traps containing uraniferous soils. Microorganisms. 2019;7(9):324. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R., Rao R., Sain M., Mangal P., Kaur P. Microbial assessment of bio-medical waste from different health care units of bikaner. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2020;9(1):1808–1815. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2020.901.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Sato Y., Kawashima M., Furumichi M., Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D457–D462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar A., Sharma P., Dahiya S., Singh H., Kapil A., Kaur P. Genomic profiling of antimicrobial resistance genes in clinical isolates of Salmonella Typhi from patients infected with Typhoid fever in India. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):8299. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64934-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami H., Inuzuka H., Hori N., Takahashi N., Ishida K., Mochizuki K., Ohkusu K., Muraosa Y., Watanabe A., Kamei K. Inhibitory effects of antimicrobial agents against Fusarium species. Med. Mycol. 2015;53(6):603–611. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myv016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny C., Priyadarshini A. Review of current healthcare waste management methods and their effect on global health. Healthcare. 2021;9(3):284. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9030284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan B.A., Khan A.A., Ali M., Cheng L. Greenhouse gas emission from small clinics solid waste management scenarios in an urban area of an underdeveloping country: a life cycle perspective. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2019;69(7):823–833. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2019.1578297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S. Microbiota in Rosacea. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020;21(S1):25–35. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00546-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassert T.E., Leistner R., Zubiria-Barrera C., Stock M., López M., Neubert R., Driesch D., Gastmeier P., Slevogt H. Bacterial colonization dynamics and antibiotic resistance gene dissemination in the hospital environment after first patient occupancy: a longitudinal metagenetic study. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollu V.K.R., Kumar P., Gautam K. Comparison of microwave and autoclave treatment for biomedical waste disinfection. Systems Microbiology and Biomanufacturing. 2022;2(4):732–742. doi: 10.1007/s43393-022-00101-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt A.F., Mete B., Houssein F.M., Tok Y., Kuskucu M.A., Yucebag E., Urkmez S., Tabak F., Aygun G. A pan-resistant Myroides odoratimimus catheter-related bacteremia in a COVID-19 patient and review of the literature. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2022 doi: 10.1556/030.2022.01702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J., Li Y., Yang W., Dong R., Liang Y., Liu J., Chen L., Wang W., Ji B., Tian G., Che N., Meng B. Genomic and resistome analysis of Alcaligenes faecalis strain PGB1 by nanopore MinION and illumina technologies. BMC Genom. 2022;23(S1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08507-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson D.G.J., Flach C.-F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022;20(5):257–269. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00649-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luplertlop N. Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium complex species: from saprobic to pathogenic fungus. J. Mycolog. Med. 2018;28(2):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguigan K.L., Al-Shaer M.H., Peloquin C.A. Beta-lactams dosing in critically ill patients with gram-negative bacterial infections: a pk/pd approach. Antibiotics. 2021;10(10):1–14. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10101154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi A.B., Gomes C. Effects of microwave radiation on micro-organisms in selected materials from healthcare waste. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;16(3):1277–1288. doi: 10.1007/s13762-018-1741-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.Journal. 2011;17(1):10. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo Y., Komiya S., Yasumizu Y., Yasuoka Y., Mizushima K., Takagi T., Kryukov K., Fukuda A., Morimoto Y., Naito Y., Okada H., Bono H., Nakagawa S., Hirota K. Full-length 16S rRNA gene amplicon analysis of human gut microbiota using MinIONTM nanopore sequencing confers species-level resolution. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo T., Mori N., Kawai F., Sakurai A., Toyoda M., Mikami Y., Uehara Y., Furukawa K. Vagococcus fluvialis as a causative pathogen of bloodstream and decubitus ulcer infection: case report and systematic review of the literature. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021;27(2):359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawioo P.M., Garcia H.A., Hooijmans C.M., Velkushanova K., Simonič M., Mijatović I., Brdjanovic D. A pilot-scale microwave technology for sludge sanitization and drying. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;601–602:1437–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.O., Buckwalter S.P., Henry M.W., Wu F., Maloney K.F., Abraham B.K., Hartman B.J., Brause B.D., Whittier S., Walsh T.J., Schuetz A.N. Globicatella sanguinis osteomyelitis and bacteremia: review of an emerging human pathogen with an expanding spectrum of disease. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017;4(1):1–5. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan B., Zaman K., Anand N., Taneja N. Aerococcus viridans: a rare pathogen causing urinary tract infection. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017;11(1):DR01–DR03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23997.9229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka H., Oka K., Yamada Y., Nakane Y., Komiya H., Murase C., Iguchi M., Yagi T. Lysinibacillus fusiformis bacteremia: case report and literature review. J. Infect. Chemother. 2022;28(2):315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2021.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y., Itoh M., Okuda S., Yoshizawa A.C., Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. Web Server), W182–W185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser A.I., Campos-Madueno E.I., Keller P.M., Endimiani A. Complete genome sequence of a third- and fourth-generation cephalosporin-resistant Comamonas kerstersii isolate. Microbiology Resource Announcements. 2021;10(28):14–16. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00391-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information . PubChem; 2022. Enzyme Summary for Enzyme 3.5.2.6.https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/EC:3.5.2.6 Beta-lactamase (EC 3.5.2.6) [Google Scholar]

- Nidoni P.G. Incineration process for solid waste management and effective utilization of by Products. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology. 2017:378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson R.H., Larsson K.H., Taylor A.F.S., Bengtsson-Palme J., Jeppesen T.S., Schigel D., Kennedy P., Picard K., Glöckner F.O., Tedersoo L., Saar I., Kõljalg U., Abarenkov K. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D259–D264. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noman E.A., Al-Gheethi A., Rahman N.N.N.A., Nagao H., Ab Kadir M. Assessment of relevant fungal species in clinical solid wastes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2016;23(19):19806–19824. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberacker P., Stepper P., Bond D.M., Höhn S., Focken J., Meyer V., Schelle L., Sugrue V.J., Jeunen G.J., Moser T., Hore S.R., von Meyenn F., Hipp K., Hore T.A., Jurkowski T.P. Bio-On-Magnetic-Beads (BOMB): open platform for high-throughput nucleic acid extraction and manipulation. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(1):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]