Abstract

Background:

Bullying may undermine patient safety in healthcare organizations threatening quality improvement and patient outcomes.

Purpose:

To explore the associations between the nursing work environment, nurse-reported workplace bullying, and patient outcomes.

Method:

Cross-sectional analysis of nurse survey data (N = 943). The Practice Environment Scale of the nursing work index was used to measure the work environment, nurse-reported bullying was measured with the short negative acts questionnaire, and single items measured care quality and patient safety grade. Random effects logistic regressions were used to determine associations controlling for individual, employment, and organizational factors.

Findings:

Fourty percent of nurses reported experiencing bullying. A higher work environment composite score was significantly associated with a lower risk of bullying (OR = 0.16 [0.12, 0.22], p < .0001). Nurses experiencing bullying were less likely to report good/excellent quality of care (OR = 0.28 [0.18, 0.44], p < .0001) or a favorable patient safety grade (OR = 0.36 [0.25, 0.51], p < .0001).

Discussion:

The nursing work environment influences the presence of bullying, which can negatively impact patient outcomes. Improving nurse work environments is one mechanism to better address nurse bullying.

Keywords: nursing, patient safety, quality of care, violence, work environment, workplace bullying

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Nurses are instrumental in ensuring high-quality, safe patient care, a fundamental expectation of an efficient, and effective healthcare system. To enhance patient outcomes, healthcare organizations and nursing management can improve the organizational context in which care is provided.1 The nursing work environment is a system foundation for nursing practice.2 Favorable nursing work environments facilitate improved nurse outcomes, which enables nurses to optimally perform and provide quality patient care.2 Nurses’ exposure to workplace bullying may negatively influence nurse well-being and patient outcomes. In this study, we define workplace bullying as any negative behavior, exhibited by an individual or group of either perceived or actual power, that was repeatedly and persistently directed toward another individual, who had difficulty defending him- or herself against the behavior, for a prolonged time frame (i.e., at least 6 months).3

Despite a substantial and growing body of evidence reflecting the negative effects of workplace bullying, nurses continue to experience and report workplace bullying internationally.4 In their review of the literature, Serafin et al.5 report that 17%–94% of nurses experience workplace bullying. Estimates of workplace bullying are difficult to obtain due to differences in workplace bullying definitions and questionnaires used in research.6 The experience of workplace bullying in healthcare organizations may undermine safety culture in the workplace, potentially affecting the quality of nursing care and patient safety.7

1.1 |. Workplace bullying in the nursing profession

Empirical evidence establishes a clear link between experiencing workplace bullying and poor mental and physical health among nurses, job dissatisfaction, decreased job performance, and an increased intent to leave their current job or the nursing profession entirely.7,8 Due to the poor nursing outcomes associated with experiencing workplace bullying and the strong associations between nursing and patient outcomes, there is a potential link between nurses experiencing workplace bullying and poor patient outcomes.7

After over 3 decades of nurse-reported workplace bullying inquiry, researchers have speculated various explanations for workplace bullying in nursing, including individual (e.g., personality), and organizational (e.g., organizational culture, leadership styles, performance demands) factors. Understanding exposure to workplace bullying and its effects requires focusing on a combination of individual and organizational factors. Because most individual nurse factors are not modifiable, exploring organizational factors that may contribute to the presence of workplace bullying in nursing would likely be a productive focus for research and the development of organizational-level interventions to decrease workplace bullying.

1.2 |. Organizational factors and nurse-reported workplace bullying

Healthcare organizations are characterized as stressful for a multitude of reasons, including frequent organizational changes, performance demands, interprofessional collaboration, and rapid decision-making that have implications for care delivery and patient outcomes.9 These stressors are compounded by a system-wide emphasis on cost containment, productivity, and efficiency while nurses concurrently experience organizational constraints, high acuity workloads, and differing leadership and managerial styles.10 Each of these organizational stressors is directly associated with increased rates of workplace bullying. However, these stressors also frequently conflict with nurses’ goals of providing compassionate care.11 As a result, nurses often report high levels of role conflict, role ambiguity, and poor job control,10,12 all of which also are associated with increased reports of workplace bullying.

The nursing work environment is described as the organizational characteristics of a work setting that either facilitate or hinder nurses from delivering high-quality, professional nursing care.13 The nursing work environment encompasses five domains (i.e., nurse participation in hospital affairs; nursing foundations for quality care; nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses; staffing and resource adequacy; and collegial nurse—physician relations) that were empirically tested with exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses.13 To the authors’ knowledge, only one study explores the association between the nursing work environment, as measured by the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index and workplace bullying.14 Significant bivariate associations were reported between all five domains of the nursing work environment and the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index composite score and workplace bullying.

1.3 |. Nurse-reported workplace bullying and patient outcomes

Few studies have empirically examined the association between nurse-reported workplace bullying and patient outcomes.15 Of the studies that exist, the association remains inconclusive; however, the majority support an association between nurse-reported workplace bullying (or other disruptive workplace behaviors) and poor patient outcomes. Using nurse-reported patient outcomes, varying types of disruptive workplace behaviors, including workplace bullying, have been shown to be associated with poorer patient care quality, adverse events (i.e., medication errors, nosocomial infections, falls, work-related injury, and patient complaints), and patient safety risk.16 However, additional evidence suggests that nurses do not perceive their experiences of workplace bullying to influence job performance12 or patient safety.17 When exploring direct patient outcomes, Arnetz et al.15 found that nurse-reported workplace bullying was associated with central line-associated bloodstream infections, but not significantly associated with patient falls, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, pressure injury, or ventilator-associated events. Additional evidence is needed to further determine the association between nurses experiencing workplace bullying and patient outcomes.

1.4 |. Theoretical framework

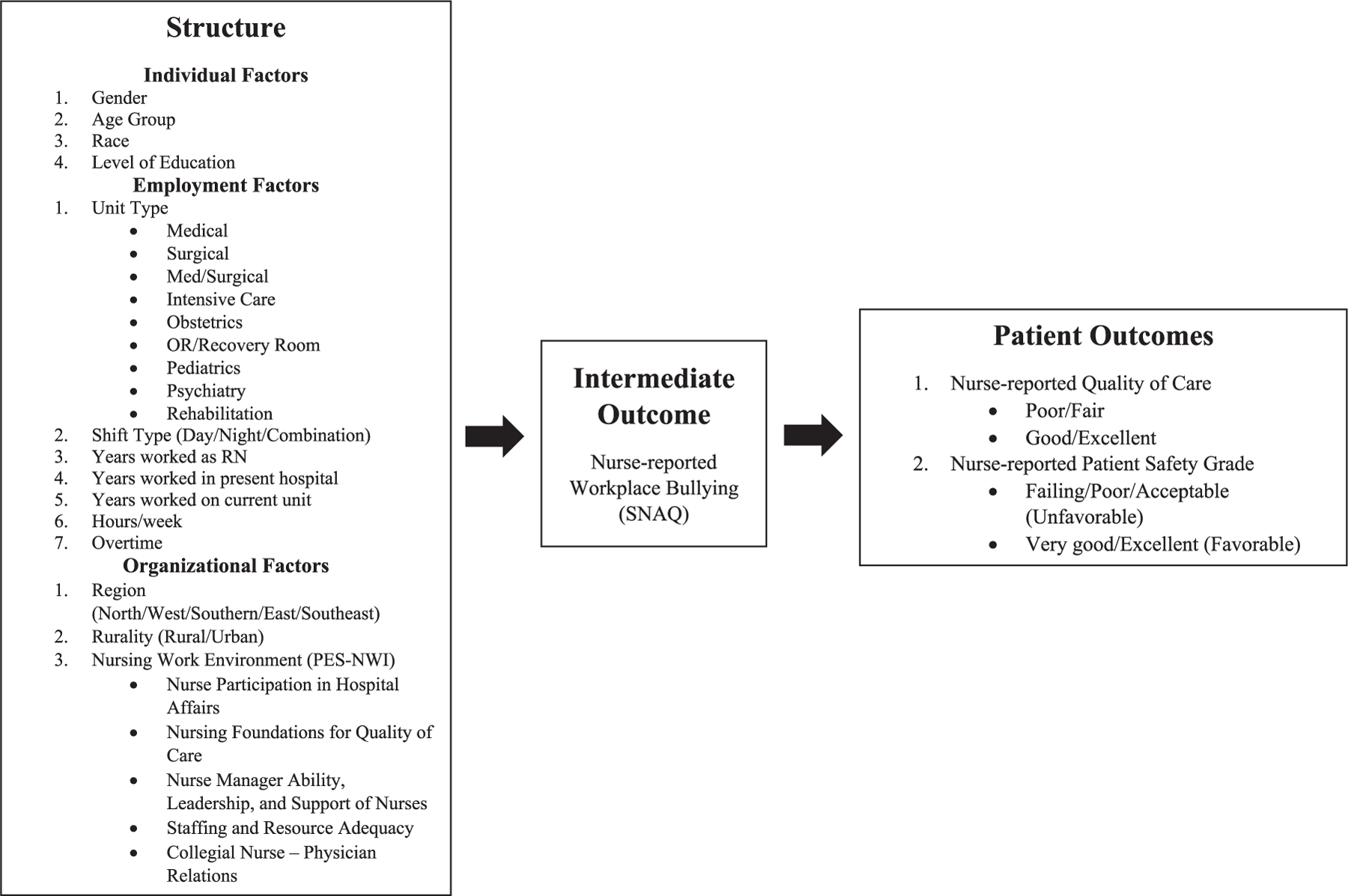

The theoretical framework that guided this study was a modification of Donabedian’s (1996) structure, process, and outcome framework (Figure 1). Donabedian proposed using a triad of categories to evaluate health care quality. These categories include structure (i.e., settings, provider qualifications, and administrative systems through which patient care occurs), process (i.e., components of patient care delivered), and outcome (i.e., focuses on patient recovery, restoration of function, and survival).18 Using Donabedian’s framework, the purpose of this paper is to first explore the association between the nursing work environment (i.e., structure) and nurse-reported workplace bullying (i.e., intermediate outcome) and second, the association between nurse-reported workplace bullying and nurse-reported patient outcomes (i.e., quality of care and patient safety grade). The use of cross-sectional data which only provides “snapshots” of the workplace bullying phenomenon inhibits the ability to examine workplace bullying as a process.3 Examining workplace bullying as a process would require studies to test a priori models with multiple assessment points that can capture the dynamics of workplace bullying over short and long time periods.3 Therefore, “process” was not explored in this study.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework note. Conceptual framework depicting the associations tested between the nursing work environment (i.e., structure), and nurse-reported workplace bullying (i.e., patient outcomes).

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Design, sample, and data sources

This cross-sectional study was part of a larger statewide study of nurses working throughout Alabama. Additional information regarding data collection and survey methods is published elsewhere. In brief, staff nurses who were currently employed at an acute care hospital in an inpatient setting within the state of Alabama were included in the study. Advanced practice nurses or nurses who were not currently employed, worked in an outpatient setting or had an Alabama nursing license but an out-of-state address were excluded. A total of 1354 inpatient staff nurses responded to the web-based survey of which 943 nurses completed the Short Negative Acts Questionnaire, the instrument used to measure nurse-reported workplace bullying. Data collection occurred between July 2018 and mid-January 2019 due to a low response rate. We were unable to increase the individual nurse sample size. Data from 89 of 124 Alabama hospitals (72%) were represented in the study. Due to the low response rate, associations were evaluated at the .05 and .10 significance levels to help control for type II error.

2.2 |. Study variables

2.2.1 |. Nurse-reported workplace bullying

Nurse-reported workplace bullying was measured using the Short Negative Acts Questionnaire, a nine-item behavioral instrument that determines the perception of work-related, person-related, and physically intimidating bullying behaviors in the workplace.19 The short negative acts questionniare was derived from the Revised Negative Acts Questionnaire and does not include a question that identifies the perpetrator(s) of workplace bullying. Nurses were asked to report the frequency of experiencing each of the nine behaviors listed in the Short Negative Acts Questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale (never = 1, now and then = 2, monthly = 3, weekly = 4, or daily = 5). A latent class analysis (LCA) was used to identify the bully status of nurses.20 An LCA systematically classifies respondents into mutually exclusive groups with respect to a given trait (i.e., exposure to workplace bullying) that is not directly observed.20 The advantage of the LCA approach includes the objective identification of groups based on data, independent of distributional assumptions.20 Based on the results of the LCA, we dichotomized participating nurses into either bullied or not bullied groups. The Short Negative Acts Questionnaire had a Cronbach’s α of .89 in this sample.

2.2.2 |. Nurse-reported quality of care

Healthcare quality is “the assessment and provision of effective and safe care, reflected in a culture of excellence, resulting in the attainment of optimal or desired health.”21 In this study, nurse-reported quality of care was assessed using a single-item measure. Nurses were asked to answer the question: “In general, how would you describe the quality of nursing care on your unit?” The responses included: poor, fair, good, and excellent. For analyses, the responses were dichotomized into either poor/fair or good/excellent quality of care. This measure has demonstrated high validity as it reflects differences in quality as measured by standard process indicators and patient outcomes (i.e., mortality and failure to rescue).22

2.2.3 |. Nurse-reported patient safety grade

Nurse-reported patient safety grade was assessed using a single-item measure included in the AHRQ’s hospital survey on patient safety culture.23 In this survey, AHRQ defines patient safety as the “avoidance and prevention of patient injuries or adverse events resulting from the processes of health care delivery.”23 The single-item asked nurses to respond to the statement: “Please give your work area/unit in this hospital an overall grade on patient safety.” The self-report responses included: excellent, very good, acceptable, poor, or failing. For analysis, the responses were dichotomized into either a favorable patient safety grade (excellent and very good), or an unfavorable patient safety grade (acceptable, poor, and failing). Nurse-reported patient safety grade has a moderate to high correlation with the composite scores of the AHRQ’s hospital survey on patient safety culture.24

2.2.4 |. Nursing work environment

The nursing work environment was measured using the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index.13 The Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index is a 31-item, empirically developed instrument that aims to measure modifiable factors in the nursing work environment.13 In the survey, nurses indicated the extent to which certain work environment characteristics are present in their current job.13 Using a 4-point Likert scale, the nurses’ responses were coded as strongly disagree = 1, somewhat disagree = 2, somewhat agree = 3, or strongly agree = 4. Each of the subscales was scored separately by calculating the mean of the items within the subscale. The subscale means were averaged to create a Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index composite score.13 Scores close to 3.00 indicate that participants “agree” that the desirable characteristics are present in their nursing work environment. The Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index has strong construct, discriminant, and concurrent validity and good subscale and composite score internal consistency reliability (α ≥ .70).25 In this sample, the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index had an overall Cronbach’s α of .96, indicating high internal consistency reliability.26 The reliability of the individual subscales also was high with the Cronbach’s α ranging from .86 to .90 in this sample.

2.2.5 |. Individual, employment, and organizational factors

Individual, employment, and organizational factors were assessed using one-item measures. Individual factors included gender, age group, race, and level of education. Employment factors included unit type, shift type, years worked asa registered nurse, years worked in the present hospital, years worked on the current unit, worked hours/week, and worked overtime/week. Organizational factors included region, rurality, and the nursing work environment, which was measured using the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index.

2.3 |. Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using R version 3.4.3. The descriptive statistics were summarized as median and range for continuous variables and as frequency and proportion for categorical variables. To determine the factors associated with nurse-reported workplace bullying, we conducted bivariate analyses using random-effects logistic regression accounting for the hierarchical nature of the data (i.e., nurses nested within hospitals).27 Nurse-reported workplace bullying was the dependent variable and each of the individual, employment, and organizational factors were independent variables, with the hospital as the random effect. The strength of each association was determined by the unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) (95% CI [lower limit, upper limit]). The associations between nurse-reported workplace bullying and the nursing work environment (the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index subscales and the composite scores) were examined with bivariate analyses. Further, the adjusted associations between nurse-reported workplace bullying and the nursing work environment were assessed using multiple random effects logistic regression modeling, with nurse-reported workplace bullying as the dependent variable, each of the individual subscale scores along with the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index composite score as the independent variable, and hospital as a random effect, adjusting for covariates. These covariates were selected based on their theoretical relevance and/or the p values (≤0.200) in the bivariate analyses aforementioned.28 In cases of multicollinearity caused by highly correlated covariates, only the variables with the most theoretical relevance were included. The adjusted ORs and 95% CIs were obtained from the multiple regression modeling. Similar analyses were conducted to assess the factors associated with nurse-reported patient outcomes and to explore the unadjusted and adjusted association between patient outcomes and nurse-reported workplace bullying.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Factors associated with nurse-reported workplace bullying

The LCA of the Short Negative Acts Questionnaire suggested that 40% (n = 377) of nurses reported experiencing workplace bullying in the past 6 months. Descriptive statistics of the nursing sample are provided in Table 1. The bivariate analysis suggested that education (i.e., individual factor), worked hours/week, and worked overtime/week (i.e., employment factors) were associated with nurse-reported workplace bullying (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics of studying sample (N = 943)

| Factor | Median or n | Range or % |

|---|---|---|

| Individual factors | ||

| Age | ||

| 21–30 | 336 | 36.0 |

| 31–40 | 190 | 20.3 |

| 41–50 | 154 | 16.5 |

| >50 | 254 | 27.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 96 | 10.4 |

| Female | 826 | 89.6 |

| Race | ||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 104 | 11.5 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 739 | 82.0 |

| Other | 58 | 6.4 |

| Education level | ||

| Diploma/Associate Degree | 304 | 32.8 |

| Undergraduate | 521 | 56.1 |

| Graduate (Master or Doctorate) | 103 | 11.1 |

| Employment factors | ||

| Years worked as a registered nurse | 8.00 | 0–50 |

| Years worked in present hospital | 4.00 | 0–42 |

| Years worked on current unit | 3.00 | 0–60 |

| Unit type | ||

| Medical | 83 | 8.8 |

| Surgical | 71 | 7.6 |

| Med/surgical | 258 | 27.5 |

| Intensive care unit | 310 | 33.0 |

| Obstetrics | 91 | 9.7 |

| Operating room/recovery room | 47 | 5.0 |

| Pediatrics | 31 | 3.3 |

| Psychiatry | 30 | 3.2 |

| Rehabilitation | 17 | 1.8 |

| Shift type | ||

| Day | 571 | 60.7 |

| Evening/night | 321 | 34.1 |

| Combination (day/night) | 49 | 5.2 |

| Hours/week | 36 | 0–60 |

| Overtime/week | 2 | 0–55 |

| Organizational factors | ||

| Region of Alabama | ||

| North | 74 | 7.8 |

| West | 25 | 2.7 |

| Southern | 80 | 8.5 |

| East | 607 | 64.4 |

| Southeast | 157 | 16.6 |

| Rurality | ||

| Rural | 50 | 5.3 |

| Urban | 893 | 94.7 |

TABLE 2.

Association of nurse-reported workplace bullying with individual, employment, and organizational characteristics (bivariate analysis)

| Variable | Raw OR [95% CI] | Raw p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | ||

| Gender: Male (ref = female) | 1.12 [0.72, 1.75] | .6019 |

| Age (ref = 21–30) | .3029 | |

| 31–40 | 1.39 [0.95, 2.02] | .0875 |

| 41–50 | 1.11 [0.74, 1.67] | .6171 |

| >50 | 0.99 [0.70, 1.42] | .9696 |

| Race (ref = White) | 6133 | |

| Black or African American | 0.80 [0.52, 1.25] | .3301 |

| Other | 0.93 [0.53, 1.63] | .7943 |

| Education (ref = Diploma/Associate) | .0502 | |

| Undergraduate | 1.30 [0.95, 1.77] | .0962 |

| Graduate (Master or Doctorate) | 1.76 [1.10, 2.82] | .0192 |

| Employment characteristics | ||

| Years worked as a registered nurse | 1.00 [0.98, 1.01] | .4640 |

| Years worked in present hospital | 1.00 [0.98, 1.02] | .9240 |

| Years worked on current unit | 1.01 [0.99, 1.02] | .4838 |

| Unit (ref = intensive care unit) | .1660 | |

| Medical | 1.30 [0.78, 2.14] | .3107 |

| Surgical | 0.93 [0.53, 1.61] | .7882 |

| Med/surgical | 0.94 [0.66, 1.34] | .7255 |

| Obstetrics | 0.64 [0.38, 1.08] | .0930 |

| Operating room/recovery room | 1.98 [1.04, 3.74] | .0364 |

| Pediatrics | 0.86 [0.38, 1.95] | .7168 |

| Psychiatry | 1.42 [0.66, 3.08] | .3696 |

| Rehabilitation | 1.41 [0.51, 3.91] | .5111 |

| Shift type (ref = day) | .9598 | |

| Evening/night | 0.96 [0.72, 1.28] | .8000 |

| Combination (day/night) | 1.03 [0.56, 1.89] | .9300 |

| Hours/week | 1.03 [1.02, 1.05] | <.0001 |

| Overtime/week | 1.02 [1.00, 1.04] | .0126 |

| Organizational characteristics | ||

| Region (ref = North) | .1403 | |

| West | 0.80 [0.27, 2.44] | .7004 |

| Southern | 0.59 [0.27, 1.26] | .1704 |

| East | 0.44 [0.23, 0.84] | .0129 |

| Southeast | 0.53 [0.26, 1.09] | .0839 |

| Rurality: Rural (ref = urban) | 0.68 [0.33, 1.40] | .2980 |

| Nurse participation in hospital affairs | 0.28 [0.22, 0.35] | <.0001 |

| Nursing foundations for quality of care | 0.20 [0.15, 0.27] | <.0001 |

| Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses | 0.35 [0.30, 0.42] | <.0001 |

| Staffing and resource adequacy | 0.40 [0.34, 0.48] | <.0001 |

| Collegial nurse–physician relations | 0.40 [0.33, 0.50] | <.0001 |

| Work environment composite score | 0.17 [0.13, 0.23] | <.0001 |

Note: The p values were obtained from an F test in a simple random effect logistic regression with workplace bullying as a dependent variable and hospital as a random effect.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; OR, odds ratios.

3.2 |. Association between the nursing work environment and nurse-reported workplace bullying

The Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index subscale and composite scores for the two workplace bullying status groups (i.e., not bullied and bullied) are shown in Table 3. Across all nurse respondents, regardless of workplace bullying status, the mean Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index composite score was 2.84 (SD = 0.62), and subscale scores ranged from 2.51 for Staffing and Resource Adequacy to 3.08 for Nursing Foundation for Quality of Care. Among nurses who reported being bullied, the mean Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index composite score was 2.50 (SD = 0.56), and subscale scores ranged from 2.13 for nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses to 2.82 for collegial nurse–physician relations. Among nurses who did not report being bullied, the mean Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index composite score was 3.07 (SD = 0.56), and subscale scores ranged from 2.76 for Staffing and Resource Adequacy to 3.28 for Nursing Foundations for Quality of Care.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted association between nurse-reported workplace bullying and the nursing work environment characteristics

| Model | Practice environment scale of the nursing work index | Not bullied (n = 566) mean | Not bullied (n = 566) SD | Bullied (n = 377) mean | Bullied (n = 377) SD | Not bullied versus bullied Adj. OR [CI]a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nurse participation in hospital affairs | 2.97 | 0.66 | 2.38 | 0.68 | 0.28 [0.22, 0.36] |

| 2 | Nursing foundations for quality of care | 3.28 | 0.51 | 2.79 | 0.61 | 0.21 [0.15, 0.28] |

| 3 | Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses | 3.10 | 0.77 | 2.13 | 0.79 | 0.35 [0.29, 0.43] |

| 4 | Staffing and resource adequacy | 2.76 | 0.83 | 2.39 | 0.82 | 0.34 [0.28, 0.43] |

| 5 | Collegial nurse– physician relations | 3.24 | 0.62 | 2.82 | 0.72 | 0.38 [0.30, 0.48] |

| 6 | Work environment composite score | 3.07 | 0.56 | 2.50 | 0.56 | 0.16 [0.12, 0.22] |

Abbreviations: Adj.OR, adjusted odds ratios, CI, confidence intervals; SD, standard deviation.

Models adjusted for: gender, age, race, education, unit type, hours per week, and region (all risk factors (p ≤ .200) for workplace bullying).

Bivariate analysis suggested that for every one-unit increase in the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index composite score (e.g., from a score of 2.00 to a score of 3.00) the odds of reporting being bullied decreased by 83% (OR = 0.17 [0.13, 0.23]; p < .0001). After controlling for covariates including individual (gender, race, and education), employment (work type, work status, unit type, shift length, and hours/week), and organizational (region) factors, similar results were observed with an adjusted OR of 0.16 [0.12, 0.22], p < .0001 (Table 3). Similar associations also were found between nurse-reported workplace bullying and all five subscales of the nursing work environment (Table 3).

3.3 |. Nurse-reported workplace bullying and patient outcomes

3.3.1 |. Nurse-reported quality of care

Associations between good/excellent nurse-reported quality of care and individual, employment, and organizational characteristics are reported in Table 4. Bivariate analysis suggested that nurses who experienced workplace bullying were less likely to report good/excellent nurse-reported quality of care (OR = 0.32 [0.22, 0.47], p < .0001) compared to nurses who did not experience workplace bullying. After controlling for covariates including individual (gender, race, and education), employment (unit type, years as a registered nurse, and worked hours/week), and organizational (rurality) factors, similar results were observed with an adjusted OR of 0.28 [0.18, 0.44], p < .0001.

TABLE 4.

Associations between good/excellent nurse-reported quality of care and individual, employment, and organizational characteristics (bivariate analysis)

| Variable | Raw OR [95% CI] | Raw p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | ||

| Gender: Male (ref = female) | 0.91 [0.51, 1.61] | .7390 |

| Age (ref = 21–30) | .1210 | |

| 31–40 | 0.71 [0.44, 1.13] | .1510 |

| 41–50 | 1.11 [0.64, 1.93] | .7130 |

| >50 | 1.31 [0.80, 2.14] | .2870 |

| Race (ref = White) | .0053 | |

| Black or African American | 0.59 [0.35, 1.00] | .0487 |

| Other | 0.41 [0.22, 0.76] | .0046 |

| Education (ref = Diploma/Associate) | .0216 | |

| Undergraduate | 1.19 [0.79, 1.78] | .4057 |

| Graduate (Master or Doctorate) | 0.57 [0.32, 1.00] | .0486 |

| Employment characteristics | ||

| Years worked as a registered nurse | 1.02 [1.01, 1.04] | .0114 |

| Years worked in present hospital | 1.02 [1.00, 1.05] | .0572 |

| Years worked on current unit | 1.03 [1.00, 1.06] | .0390 |

| Unit (ref = intensive care unit) | .0071 | |

| Medical | 0.44 [0.23, 0.82] | .0093 |

| Surgical | 0.64 [0.31, 1.29] | .2117 |

| Med/surgical | 0.50 [0.31, 0.78] | .0027 |

| Obstetrics | 1.18 [0.56, 2.50] | .6614 |

| Operating room/recovery room | 7.10 [0.95, 53.22] | .0565 |

| Pediatrics | 1.33 [0.38, 4.69] | .6609 |

| Psychiatry | 0.54 [0.21, 1.43] | .2145 |

| Rehabilitation | 0.64 [0.17, 2.39] | .5022 |

| Shift type (ref= day) | .2510 | |

| Evening/night | 1.12 [0.76, 1.65] | .5660 |

| Combination (day/night) | 0.60 [0.30, 1.21] | .1550 |

| Hours/week | 0.98 [0.96, 1.00] | .1090 |

| Overtime/week | 0.98 [0.96, 1.00] | .0240 |

| Organizational characteristics | ||

| Region (ref = North) | .4793 | |

| West | 0.48 [0.14, 1.63] | .2410 |

| Southern | 0.64 [0.26, 1.57] | .3260 |

| East | 0.94 [0.42, 2.10] | .8820 |

| Southeast | 1.10 [0.46, 2.62] | .8360 |

| Rurality: Rural (ref = urban) | 2.73 [0.91, 8.19] | .0732 |

| Nurse-reported workplace bullying | ||

| Bully status bullied (ref = not bullied) | 0.32 [0.22, 0.47] | <.0001 |

Note: The p values were obtained from a simple random effect logistic regression with nurse-reported quality of care as dependent variable and hospital as random effect.

3.3.2 |. Nurse-reported patient safety grade

Associations between favorable nurse-reported patient safety grades and individual, employment, and organizational characteristics are reported in Table 5. Bivariate analysis suggested that nurses who experienced workplace bullying were less likely to report a favorable patient safety grade (OR = 0.38 [0.28, 0.51], p < .0001) compared to nurses who did not experience workplace bullying. After controlling for covariates including individual (gender, race, and education), employment (unit type, shift type, years as a registered nurse, and worked hours/week), and organizational (region and rurality) factors, similar results were observed with an adjusted OR of 0.36 [0.25, 0.51], p < .0001.

TABLE 5.

Associations between favorable nurse-reported patient safety grade and individual, employment, and organizational characteristics (bivariate analysis)

| Variable | Raw OR [95% CI] | Raw p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | ||

| Gender: Male (ref = female) | 1.16 [0.71, 1.88] | .5570 |

| Age (ref = 21–30) | .0122 | |

| 31–40 | 1.30 [0.86, 1.96] | .2134 |

| 41–50 | 0.87 [0.57, 1.33] | .5127 |

| >50 | 1.71 [1.15, 2.54] | .0075 |

| Race (ref = White) | .0021 | |

| Black or African American | 0.59 [0.38, 0.91] | .0177 |

| Other | 0.45 [0.25, 0.78] | .0045 |

| Education (ref = Diploma/Associate) | .0218 | |

| Undergraduate | 1.28 [0.93, 1.78] | .1353 |

| Graduate (Master or Doctorate) | 0.70 [0.43, 1.13] | .1412 |

| Employment characteristics | ||

| Years worked as a registered nurse | 1.01 [1.00, 1.03] | .0586 |

| Years worked in present hospital | 1.02 [1.00, 1.04] | .0385 |

| Years worked on current unit | 1.03 [1.01, 1.06] | .0065 |

| Unit type (ref= intensive care unit) | <.0001 | |

| Medical | 0.51 [0.29, 0.87] | .0143 |

| Surgical | 0.48 [0.27, 0.85] | .0123 |

| Med/surgical | 0.32 [0.22, 0.47] | <.0001 |

| Obstetrics | 1.01 [0.56, 1.81] | .9782 |

| Operating room/recovery room | 3.18 [1.09, 9.31] | .0349 |

| Pediatrics | 1.10 [0.42, 2.89] | .8527 |

| Psychiatry | 0.66 [0.28, 1.54] | .3342 |

| Rehabilitation | 0.30 [0.11, 0.84] | .0225 |

| Shift type (ref = day shift) | .1251 | |

| Evening shift/night shift | 1.15 [0.84, 1.57] | .3886 |

| Combination (both day–night shift) | 0.59 [0.32, 1.10] | .0958 |

| Hours/week | 0.99 [0.97, 1.01] | .1878 |

| Overtime/week | 0.99 [0.97, 1.00] | .1240 |

| Organizational characteristics | ||

| Region (ref = North) | .0007 | |

| West | 0.34 [0.13, 0.87] | .0236 |

| Southern | 1.06 [0.54, 2.07] | .8657 |

| East | 1.41 [0.85, 2.36] | .1874 |

| Southeast | 0.80 [0.45, 1.43] | .4574 |

| Rurality: Rural (ref = urban) | 3.15 [1.27, 7.80] | .0132 |

| Nurse-reported workplace bullying | ||

| Bully Status Bullied (ref = not bullied) | 0.38 [0.28, 0.51] | <.0001 |

Note: The p values were obtained from a simple random effect logistic regression with nurse-reported patient safety grade as dependent variable and hospital as random effect.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This study explored the association between the nursing work environment and nurse-reported workplace bullying, and nurse-reported workplace bullying and patient outcomes (i.e., nurse-reported quality of care and patient safety grade) among inpatient staff nurses working in Alabama. The findings indicate that the nursing work environment is significantly associated with nurse-reported workplace bullying and that nurse-reported workplace bullying is associated with poorer patient outcomes.

4.1 |. Frequency of nurse-reported workplace bullying

Forty percent of nurses reported experiencing workplace bullying in the past 6 months. Nurses were more likely to report experiencing workplace bullying if they had a graduate degree and worked more hours/week or more overtime hours/week. Interestingly, individual factors including gender, age group, and race were not significantly associated with nurse-reported workplace bullying. In addition, workplace bullying was not significantly associated with years as a registered nurse, years worked in the present hospital, or years worked in the current unit. These findings, along with age group being nonsignificant, contradict nursing research that indicates newly licensed nurses are at the highest risk for experiencing workplace bullying and that the more clinical experience, seniority, or familiarity with a unit/hospital a nurse has, the less likely they are to be bullied.14 Additionally, our bivariate findings indicate that unit type was not significantly associated with nurse-reported workplace bullying, which contradicts literature underscoring that fast-paced units characterized by higher patient acuity (e.g., operating room or intensive care) often have higher rates of workplace bullying.7 Based on our findings, it would be beneficial to broaden the focus of workplace bullying to the nursing workforce in general rather than a specific group of nurses and emphasize the need to further explore organizational factors for intervention development, as nurse-reported workplace bullying can transcend individual and employment factors.

4.2 |. Nurse-reported workplace bullying and the nursing work environment

Until recently, research using the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index to measure the nursing work environment has largely focused on the instrument’s composite score, with minimal analysis conducted using the individual subscale scores.25 Exploring the subscales of the work environment that have the strongest associations with nurse-reported workplace bullying could provide healthcare organizations, and nursing management with actionable data that could appropriately inform strategies to decrease nurse-reported workplace bullying from an organizational level.

In this study, although all five domains of the nursing work environment were significantly associated with nurse-reported workplace bullying, Nursing Foundations for Quality Care had the strongest association (OR = 0.21 [0.15, 0.28], p < .0001), followed by Nurse Participation in Hospital Affairs (OR = 0.28 [0.22, 0.36], p < .0001) were the most indicative of workplace bullying after adjusting for individual, employment, and organizational factors (i.e., gender, age, race, education, unit type, hours per week, and region). Both domains reflect aspects of the nursing work environment that empower nurses through promoting autonomy, increasing nurses’ control over their practice, and providing organizational support.29 This finding is not surprising given that role conflict, role ambiguity, poor job control, and a lack of autonomy10,12 are all associated with increased reports of workplace bullying. These findings reinforce the importance of encouraging hospitals, and nursing management to support their nursing workforce through improving the nursing work environment and focusing on these two domains in particular.

4.3 |. Nurse-reported workplace bullying and patient outcomes

Our study supports an association between nurse-reported workplace bullying and poorer nurse-reported patient outcomes (i.e., quality of care and patient safety grade). Nurses experiencing workplace bullying were less likely to report good/excellent quality of care (OR = 0.28 [0.18, 0.44], p < .0001) or a favorable patient safety grade (OR = 0.35 [0.25, 0.51], p < .0001) after adjusting for respective individual, employment, and organizational factors. These findings add to the growing body of literature on the link between nurses’ experiences of workplace bullying and patient outcomes. Previous research shows that improving nursing work environments has an additive benefit of improving nurse, patient, and organizational outcomes.2 In the wider context of improving patient care and increasing patient satisfaction, the negative influence of workplace bullying on patient outcomes should facilitate improvements in the nursing work environment as an avenue for workplace bullying intervention and better outcomes.

4.4 |. Limitations

This study used cross-sectional data and therefore, we cannot determine causal relationships between variables or examine workplace bullying as a process, which would increase our understanding of how workplace bullying evolves, escalates, and deescalates over time. The small sample size and targeting of inpatient staff nurses working in hospital settings in one state increase the potential for type II error and limit the generalizability of the findings to nurses working in other settings. We also were unable to identify the perpetrators of workplace bullying toward nurses. Additionally, although nurses are valuable informants of the overall quality and safety in hospitals, nurse-reported patient outcomes were assessed using one-item measures rather than direct outcomes provided by institutional data.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

Overall, our findings support the conclusion that the nursing work environment contributes to nurse-reported workplace bullying, and that workplace bullying may threaten the quality of care and patient safety. Notably, our findings also indicate that workplace bullying can transcend individual and employment level factors and therefore cannot be addressed in the workplace by focusing on the individual, employment, or organizational factors alone.30 Nurse-reported workplace bullying is a multicausal phenomenon that will require commitment by nurses, nursing management, and healthcare organizations to combat such behaviors through employing multifaceted approaches, with improving the nursing work environment as one approach.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Alabama Board of Nursing and the Alabama Hospital Staff Nurse Study research team for their assistance and collaboration. The authors also extend many thanks to the nurses who devoted their time to participate in the Alabama Hospital Staff Nurse Study. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Rachel Z. Booth Endowment at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Nursing (Principal Investigator: Patricia A. Patrician) and the 2017 American Association of Occupational Health Nurses New Investigator Research Grant (Principal Investigator: Aoyjai Prapanjaroensin Montgomery), funded by Kelly Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses.

Funding information

National Institute of Nursing Research, Grant/Award Number: T32NR007104

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

IRB Approval—This study was reviewed by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board (IRB-300002843). This study was approved by the University-affiliated Institutional review board (IRB #3000002843).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sloane DM, Smith HL, McHugh MD, Aiken LH. Effect of changes in hospital nursing resources on improvements in patient safety and quality of care: a panel study. Med Care 2018;56(12):1001–1008. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lake ET, Sanders J, Duan R, Riman KA, Schoenauer KM, Chen Y. A meta-analysis of the associations between the nurse work environment in hospitals and 4 sets of outcomes. Med Care 2019;57(5): 353–361. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen MB, Einarsen SV. What we know, what we do not know, and what we should and could have known about workplace bullying: an overview of the literature and agenda for future research. Aggress Violent Behav 2018;42:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford CL, Chu F, Judson LH, et al. An integrative review of nurse-to-nurse incivility, hostility, and workplace violence: a GPS for nurse leaders. Nurs Adm Q 2019;43(2):138–156. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serafin L, Sak-Dankosky N, Czarkowska-Pączek B. Bullying in nursing evaluated by the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 2020;76(6): 1320–1333. doi: 10.1111/jan.14331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang YM, Zhou LJ. Workplace bullying among operating room nurses in China: a cross-sectional survey. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2021;57(1):27–32. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Joint Commission. Quick Safety Issue 24. Bullying has no place in health care June 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/newsletters/quick-safety/quick-safety-issue-24-bullying-has-no-place-in-health-care/#.YjOPu3pKiUk

- 8.Brewer KC, Oh KM, Kitsantas P, Zhao X. Workplace bullying among nurses and organizational response: an online cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag 2020;28(1):148–156. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faremi FA, Olatubi MI, Adeniyi KG, Salau OR. Assessment of occupational related stress among nurses in two selected hospitals in a city southwestern Nigeria. Int J Africa Nurs Sci 2019;10:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2019.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trépanier SG, Fernet C, Austin S, Boudrias V. Work environment antecedents of bullying: a review and integrative model applied to registered nurses. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;55:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tierney S, Bivins R, Seers K. Compassion in nursing: solution or stereotype. Nurs Inquiry 2019;26(1):e12271. doi: 10.1111/nin.12271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen E, Bjaalid G, Mikkelsen A. Work climate and the mediating role of workplace bullying related to job performance, job satisfaction, and work ability: a study among hospital nurses. J Adv Nurs 2017;73(11):2709–2719. doi: 10.1111/jan.13337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lake ET. Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Res Nurs Health 2002;25(3):176–188. doi: 10.1002/nur.10032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama M, Suzuki M, Takai Y, Igarashi A, Noguchi-Watanabe M, Yamamoto-Mitani N. Workplace bullying among nurses and their related factors in Japan: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 2016;25(17-18):2478–2488. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnetz JE, Sudan S, Fitzpatrick L, et al. Organizational determinants of bullying and work disengagement among hospital nurses. J Adv Nurs 2019;75(6):1229–1238. doi: 10.1111/jan.13915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houck NM, Colbert AM. Patient safety and workplace bullying: an integrative review. J Nurs Care Qual 2017;32(2):164–171. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chipps E, Stelmaschuk S, Albert NM, Bernhard L, Holloman C. Workplace bullying in the OR: results of a descriptive study. AORN J 2013;98(5):479–493. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2013.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q 2005;83(4):691–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Notelaers G, Van der Heijden B, Hoel H, Einarsen S. Measuring bullying at work with the short-negative acts questionnaire: identification of targets and criterion validity. Work Stress 2019;33(1):58–75. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2018.1457736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reknes I, Notelaers G, Magerøy N, et al. Aggression from patients or next of kin and exposure to bullying behaviors: a conglomerate experience. Nurs Res Pract 2017;2017:e1502854. doi: 10.1155/2017/1502854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen-Duck A, Robinson JC, Stewart MW. Healthcare quality: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum 2017;52(4):377–386. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHugh MD, Stimpfel AW. Nurse reported quality of care: a measure of hospital quality. Res Nurs Health 2012;35(6):566–575. doi: 10.1002/nur.21503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorra JS, Streagle S, Famolaro T, Yount N, Behm J. AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture: user’s guide 2018. Accessed February 18, 2020. https://www.ahrq.gov/sops/surveys/hospital/index.html

- 24.Sorra JS, Dyer N. Multilevel psychometric properties of the AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10(1):199. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swiger PA, Patrician PA, Miltner RSS, Raju D, Breckenridge-Sproat S, Loan LA. The Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index: an updated review and recommendations for use. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;74:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ 1997;314(7080):572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li B, Lingsma HF, Steyerberg EW, Lesaffre E. Logistic random effects regression models: a comparison of statistical packages for binary and ordinal outcomes. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11(1):77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med 2008;3(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aiken L, Patrician P. Measuring organizational traits of hospitals: the revised nursing work index. Nurs Res 2000;49:146–153. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200005000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathisen G, Øgaard T, Einarsen S. Individual and situational antecedents of workplace victimization. Int J Manpow 2012;33(5): 539–555. doi: 10.1108/01437721211253182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.