Abstract

Background:

Data are limited on outcomes after heart transplantation in patients bridged-to-transplantation (BTT) with a total artificial heart (TAH-t).

Methods:

The UNOS database was used to identify 392 adult patients undergoing heart transplantation after TAH-t BTT between 2005-2020. They were compared with 11,014 durable left ventricular assist device (LVAD) BTT patients and 22,348 de novo heart transplants (without any durable VAD or TAH-t BTT) during the same period.

Results:

TAH-t BTT patients had increased dialysis dependence compared to LVAD BTT and de novo transplants (24.7% vs. 2.7% vs. 3.8%) and higher levels of baseline creatinine and total bilirubin (all p<0.001). After transplantation, TAH-t BTT patients were more likely to die from multiorgan failure in the first year (25.0% vs. 16.1% vs. 16.1%, p=0.04). Ten-year survival was inferior in TAH-t BTT patients (TAH-t BTT 53.1%, LVAD BTT 61.8%, De Novo 62.6%, p<0.001), while ten-year survival conditional on 1-year survival was similar (TAH-t BTT 66.8%, LVAD BTT 68.7%, De Novo 69.0%, all p>0.20). Among TAH-t BTT patients, predictors of 1-year mortality included higher baseline creatinine and total bilirubin, mechanical ventilation, and cumulative center volume <20 cases of TAH-t explantation and heart transplantation (all p<0.05).

Conclusion:

Survival after TAH-t BTT is acceptable, and patients who survive the early postoperative phase experience similar hazards of mortality over time compared to de novo transplant patients and durable LVAD BTT patients.

Keywords: heart disease, heart transplantation, total artificial heart, biventricular failure

INTRODUCTION

Heart transplantation continues to be limited by donor shortage.1 For selected patients with end-stage heart failure, durable mechanical circulatory support devices have become an important therapeutic option. Continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) are most frequently used in this context with favorable outcomes, either as a bridge-to-transplantation (BTT) or destination therapy.2-4 In a subset of patients with severe biventricular failure or contraindications to LVAD implantation, the SynCardia total artificial heart (TAH-t, SynCardia, Tucson, Arizona) is the only commercially approved total heart replacement device for use. It has demonstrated improved survival to transplantation and post-transplantation survival compared to similar patients receiving medical management alone.5 Nevertheless, in this high-risk population, approximately 30-40% of patients do not survive to transplantation after TAH-t implantation.6-8 Previous studies have largely focused on post-implantation outcomes, and post-transplant outcomes in these patients have not been closely examined. Additionally, predictors of post-transplant mortality have yet to be identified in these patients using national registry data. This study was therefore designed to evaluate trends and outcomes of bridging to heart transplant with a TAH-t.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

This retrospective analysis was performed using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Standard Transplant Analysis and Research file as of January 1st, 2022, which included data for organ donations, transplants, and new listings occurring through December 31st, 2021. We identified 37,056 adult patients (>18 years) who underwent heart transplantation between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2020. After excluding patients who underwent heart-lung transplants, we identified 392 patients who were bridged to transplant with a TAH-t, 11,014 patients were bridged to transplant with a durable LVAD, and 22,348 patients were transplanted without any TAH-t or durable ventricular assist device bridging (de novo heart transplant). In the LVAD BTT group, we only included patients who received a Heartmate II, Heartmate III, or HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device. In the TAH-t BTT group, one patient received the AbioMed AbioCor TAH-t, while the remainder of patients received the SynCardia/Cardiowest TAH-t.

Recipient/donor characteristics and patient outcomes were defined according to the standard UNOS definitions.9 Patients with a history of previous cardiac surgery or previous heart transplants were considered to have had a prior sternotomy. Those with UNOS status 1A before the 2018 allocation policy change and status 1 or 2 afterwards were considered to have urgent status at transplant. Donor-to-recipient predicted heart mass ratio was calculated with a previously developed formula using recipient and donor age, gender, height and weight, and was used as a surrogate for donor-recipient size match.10 Recipient functional status was classified using the Karnofsky Performance Scale Index. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, with a waiver of informed consent (protocol ID: STUDY00001188, approval date 2/19/2021).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was survival after heart transplantation, truncated at 10-year follow-up. Landmark analysis was performed to assess ten-year survival conditional on 6-month and 12-month survival. This allowed us to determine whether post-transplant mortality hazards changed over time between patients who were bridged to transplant with TAH-t, durable LVAD, and those who underwent de novo heart transplant. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital complications (treated acute rejection episodes, post-transplant dialysis, stroke, and permanent pacemaker implant), hospital length of stay, and short-term mortality at 30 and 90-days after transplantation.

Statistical analyses

Baseline patient characteristics were reported as either mean +/− standard deviation or median with IQR for continuous variables depending on overall distribution and proportions for categorical variables. Between-group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables depending on the variable distribution. Pearson’s χ2-test was performed for categorical variables. Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between strata using the log-rank test, with adjustment for multiple group comparisons as needed. To ensure adequate follow-up, a sensitivity survival analysis including only patients transplanted between 2005 and 2011 was performed, and the results are included in the supplemental material.

Among patients in the TAH-t BTT group, multivariable Cox-models were constructed to evaluate predictors of early (1-year) and late (10-year) post-transplant mortality respectively. In the Cox model for 10-year post-transplant mortality, patients who died within 1-year after transplantation were excluded. Covariates found to have a p-value of <0.25 in the univariate analysis or those felt to be clinically relevant were included in the multivariable model and assessed in a stepwise fashion. The final model included only variables with a p-value of less than 0.1. The TAH-t implant era and duration between TAH-t implant and heart transplantation were forced into the final models to assess their independent effect on post-transplant mortality. Because the date of TAH-t implantation was not routinely collected before 2010, the final Cox models only included 292 out of 392 patients that had complete data. Clustering of patients within each transplant center was accounted for using a robust variance estimator in the Cox regression. The proportional hazard assumption was also checked with martingale residuals and was not violated.

Center volume was investigated as the cumulative volume of heart transplantation involving TAH-t explantation at each center during the study period and was incorporated as a binary categorical variable using 20 cases as the cutoff between low-volume (<20 cases) and high-volume centers (≥20 cases) in the final models. This cutoff was chosen after testing various cut points (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20 cases) and evaluating the associated number of centers in each volume category.

All tests were two-tailed with an alpha level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Patient population

Heart transplantation in patients bridged with TAH-t was performed in 392 patients by 51 centers between 2005 and 2020. The national volume increased from 4 cases annually in 2005 to 53 cases annually in 2013 and declined thereafter to 6 cases annually in 2020 (Supplemental Figure 1). Most centers (37/51, 72.6%) performed less than 6 cases, and 6 centers performed ≥20 cases during the study period. Total case volume per center during the study period ranged from 0 to 85 cases, and annual case volume per center ranged from 0 to 16 cases. The median time between TAH-t implant and heart transplantation (available in 292/392 patients) was 4.4 (IQR 2.5-8.2) months (range 0-33.3 months).

There were notable differences in baseline recipient characteristics between TAH-t BTT patients, durable LVAD BTT patients, and de novo heart transplant patients (Table 1). Compared to durable LVAD BTT patients and patients who underwent de novo heart transplantation, TAH-t BTT patients were younger (TAH-t BTT 52, IQR 39-59 vs. LVAD BTT 56, IQR 47-63 vs. De Novo 56, IQR 46-63 years) and more frequently male (TAH-t BTT 85.0% vs. LVAD BTT 80.3% vs. De Novo 70.0%). They had higher pre-transplant creatinine (TAH-t BTT 1.31 vs. LVAD BTT 1.20 vs. De Novo 1.20 mg/dL) and total bilirubin (TAH-t BTT 1.0 vs. LVAD BTT 0.6 vs. De Novo 0.8 mg/dL) (all p<0.001). They were also more likely to require transfusion after listing (TAH-t BTT 55.4% vs. LVAD BTT 37.1% vs. De Novo 8.8%, p<0.001), dialysis after listing (TAH-t BTT 24.7% vs. LVAD BTT 2.7% vs. De Novo 3.8%, p<0.001), and undergo heart-kidney transplantation (TAH-t BTT 15.8% vs. LVAD BTT 3.1% vs. De Novo 5.8%, p<0.001). They were more likely to have severe functional limitations before transplant (TAH-t BTT 69.6% vs. LVAD BTT 15.2% vs. De Novo 47.3%, p<0.001). Their waitlist time was longer than de novo patients (120 vs. 50 days, p<0.001) but shorter than durable LVAD BTT patients (120 vs. 201 days, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline recipient and donor characteristics

| De Novo Heart Transplant (N=22,348) |

Durable LVAD BTT (N=11014) |

TAH-t BTT (N=392) |

P-value (TAH-t BTT vs. LVAD BTT) |

P-value (TAH-t BTT vs. De Novo) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 56 (46-63) | 56 (47-63) | 52 (39-59) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.3 (23.1-29.8) | 28.6 (25.2-32.3) | 26.6 (23.2-30.5) | <0.001 | 0.17 |

| Gender: Male | 70.0 (15640) | 80.3 (8844) | 85.5 (335) | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.57 | 0.48 | |||

| White | 66.7 (14903) | 64.2 (7066) | 64.3 (252) | ||

| Black | 19.6 (4381) | 24.7 (2725) | 22.7 (89) | ||

| Hispanic | 8.9 (1992) | 7.2 (797) | 8.2 (32) | ||

| Other | 4.8 (1072) | 3.9 (426) | 4.9 (19) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 26.4 (5899) | 31.8 (3502) | 21.9 (86) | <0.001 | 0.05 |

| Dialysis after listing | 3.8 (850) | 2.7 (301) | 24.7 (97) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.20 (0.96-1.50) | 1.20 (0.98-1.48) | 1.31 (0.97-1.82) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | 0.60 (0.40-1.00) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diagnosis | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 35.5 (7938) | 38.0 (4189) | 26.5 (104) | ||

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 45.0 (10055) | 57.1 (6284) | 51.3 (201) | ||

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 5.0 (1116) | 0.9 (102) | 26.1 (24) | ||

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 3.5 (782) | 0.8 (93) | 4.3 (17) | ||

| Congenital heart disease | 4.6 (1025) | 0.6 (68) | 2.6 (10) | ||

| Others | 6.4 (1432) | 2.5 (278) | 9.2 (36) | ||

| Waitlist time (days) | 50 (15-157) | 201 (72-447) | 120 (51-241) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Urgent status | 50.6 (11298) | 62.8 (6918) | 93.9 (368) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Heart re-transplant | 5.1 (1132) | 0.1 (14) | 7.4 (29) | <0.001 | 0.04 |

| Transfusion after listing | 8.8 (1966) | 37.1 (4091) | 55.4 (217) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Multiorgan transplant | 7.1 (1592) | 3.2 (353) | 16.6 (65) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Heart-kidney transplant | 5.8 (1298) | 3.1 (343) | 15.8 (62) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ECMO | 2.0 (447) | 0.3 (32) | 0.3 (1) | 0.99 | 0.01 |

| IABP | 15.6 (3493) | 0.6 (69) | 1.8 (7) | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.9 (425) | 0.4 (46) | 3.1 (12) | <0.001 | 0.10 |

| Inotropic support | 56.0 (12522) | 7.2 (796) | 11.0 (43) | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Pre-transplant condition | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| ICU | 44.1 (9848) | 8.3 (917) | 27.3 (107) | ||

| Hospitalized: non-ICU | 15.4 (3435) | 13.4 (1475) | 56.1 (220) | ||

| Home | 40.6 (9065) | 78.3 (8622) | 16.6 (65) | ||

| Functional status | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Mild limitation | 11.9 (2662) | 19.4 (2196) | 3.1 (12) | ||

| Moderate limitation | 37.0 (8271) | 60.3 (6638) | 25.3 (99) | ||

| Severe limitation | 47.3 (10568) | 15.2 (1675) | 69.6 (273) | ||

| Unknown | 3.8 (847) | 4.6 (505) | 2.0 (8) | ||

| Donor Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 30 (22-41) | 30 (23-39) | 28 (21-37) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Gender: male | 67.4 (15069) | 76.5 (8421) | 86.0 (337) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.0 (23.0-30.9) | 26.9 (23.8-30.9) | 26.5 (23.2-30.1) | 0.03 | 0.34 |

| Gender mismatch | 27.0 (6035) | 19.9 (2187) | 18.9 (74) | 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4.1 (909) | 3.9 (428) | 2.0 (8) | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 14.9 (3319) | 15.1 (1660) | 11.5 (45) | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| Inotropic support at procurement | 45.2 (10078) | 41.7 (4587) | 43.4 (170) | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| Total ischemic time (hours) | 3.2 (2.5-3.8) | 3.2 (2.4-3.8) | 3.2 (2.5-3.9) | 0.17 | 0.35 |

| Predicted heart mass ratio (donor/recipient) | 1.02 (0.92-1.14) | 0.99 (0.90-1.10) | 1.00 (0.93-1.13) | 0.004 | 0.36 |

BTT: Bridge to Transplant; ECMO: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation; IABP: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; LVAD: Left Ventricular Assist Device; TAH-t: Total Artificial Heart

Values are in % (n) or median (interquartile range)

TAH-t BTT patients received younger donors (TAH-t BTT 28, IQR 21-37 vs. LVAD BTT 30, IQR 23-39 vs. De Novo 30, IQR 22-41 years). Donors in the TAH-t BTT group were also less likely to have gender mismatch than De Novo heart transplant patients (18.9% vs. 27.0%, p<0.001). Other differences in donor characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

Post-transplantation outcomes

Compared to durable LVAD BTT patients and patients who underwent de novo heart transplantation, patients who were bridged with TAH-t had higher rates of stroke (TAH-t BTT 8.2% vs. LVAD BTT 3.7% vs. De Novo 2.1%, p<0.001) and new dialysis requirements (TAH-t BTT 15.3% vs. LVAD BTT 11.4% vs. De Novo 9.4%, p<0.001) before discharge and longer hospital length-of-stay (TAH-t BTT 21, IQR 14-39 vs. LVAD BTT 16, IQR 11-24 vs. De Novo 14, IQR 10-22 days, p<0.001). Other in-hospital complications are outlined in Table 2. Both 30-day mortality and 90-day mortality were significantly higher in TAH-t BTT patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

In-hospital outcomes after heart transplantation and short-term mortality

| De Novo Heart Transplant (N=22,348) |

Durable LVAD BTT (N=11014) |

TAH-t BTT (N=392) |

P value (TAH-t BTT vs. LVAD BTT) |

P-value (TAH-t BTT vs. De Novo) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital Outcomes | |||||

| Treated acute rejection | 10.0 (2225) | 10.6 (1172) | 7.7 (30) | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| New dialysis requirement | 9.4 (2094) | 11.4 (1255) | 15.3 (60) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 2.1 (462) | 3.7 (406) | 8.2 (32) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Permanent pacemaker implant | 2.9 (641) | 3.0 (333) | 2.8 (11) | 0.80 | 0.94 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 14 (10-22) | 16 (11-24) | 21 (14-39) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Short-term Outcomes | |||||

| 30-day mortality | 3.4 (750) | 4.2 (465) | 9.2 (36) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 90-day mortality | 5.4 (1199) | 6.4 (708) | 12.2 (48) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

BTT: Bridge to Transplant; LVAD: Left Ventricular Assist Device; TAH-t: Total Artificial Heart

Values are in % (n) or median (interquartile range)

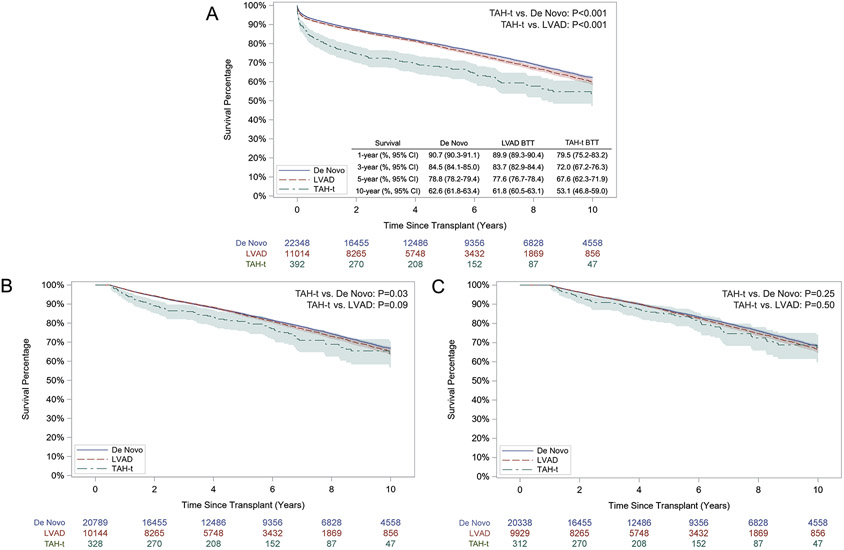

Unadjusted post-transplantation survival at 1 year, 3 years, 5 years, and 10 years after TAH-t BTT were inferior to both the de novo transplant group (p<0.001) and the durable LVAD BTT group (p<0.001, Figure 1A). In the landmark analysis, ten-year survival conditional on 6-month survival in TAH-t BTT patients was inferior to de novo heart transplant patients (p=0.03) and similar to durable LVAD BTT patients (p=0.09 Figure 1B). Ten-year survival conditional on 1-year survival was similar between different groups (Figure 1C). In the sensitivity analysis including only patients transplanted between 2005 and 2011, the results were similar, with the exception that ten-year survival conditional on 6-month survival was also similar between the TAH-t BTT patients and de novo heart transplant patients (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1. Unadjusted post-transplant survival in TAH-t bridge-to-transplant patients, durable LVAD bridge-to-transplant patients, and de novo heart transplant patients.

A. Overall survival. B. Survival conditional on 6-month survival. C: Survival conditional on 1-year survival

Number at risk and 95 percent confidence intervals are shown.

TAH-t: Total Artificial Heart

Among TAH-t BTT patients, there were 80 mortalities (20.4%) within 1 year of transplantation. Comparison of causes of death within 1 year between TAH-t BTT patients, durable LVAD BTT patients, and de novo heart transplant patients are shown in Supplemental Figure 3. Patients who were bridged to transplant with TAH-t were more likely to die from multiorgan failure within the first year after transplantation (TAH-t BTT 25.0% vs. LVAD BTT 16.1% vs. De Novo 16.1%, p=0.04 [both TAH-t BTT vs. LVAD BTT and TAH-t BTT vs. De Novo]) and infection (TAH-t BTT 27.5% vs. LVAD BTT 20.7% vs. De Novo 22.2%, p=0.15 [TAH-t BTT vs. LVAD BTT] and 0.26 [TAH-t BTT vs. De Novo]).

Risk factors for post-transplant mortality

In the unadjusted survival analysis of TAH-t BTT patients, post-transplant survival was superior in patients undergoing heart transplantation at a high-volume center (defined as cumulative volume of heart transplantation involving TAH-t explantation ≥20 cases, Supplemental Figure 4, p=0.008). Survival did not differ based on the duration between TAH-t implantation and heart transplantation (Supplemental Figure 5, p=0.93).

In the multivariable analysis, the cumulative center volume of heart transplantation after TAH-t bridging < 20 cases was an independent predictor of 1-year mortality (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.07-2.84, p=0.03), along with other recipient factors such as body mass index (BMI), ischemic cardiomyopathy, pre-transplant mechanical ventilation, creatinine, and total bilirubin (Table 3). Undergoing heart-kidney transplantation was independently associated with improved survival at 1-year (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.14-0.94, p=0.04). The era of TAH-t implantation and the interval between TAH-t implantation and transplantation were not independently associated with 1-year post-transplant mortality (Table 3). The only independent predictors of late mortality (10-year) in patients who survived past 1-year after transplantation were diabetes (HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.12-2.96, p=0.02) and black race (HR 1.94, 95% CI 1.15-3.26, p=0.01).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of predictors of short-term (1-year) post-transplant mortality in TAH-t bridge-to-transplant patients

| Variables | Adjusted Hazard Ratio |

95% Hazard Ratio Confidence Limits |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient BMI (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.11 | 0.003 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 2.17 | 1.42 | 3.32 | <0.001 |

| Pre-transplant mechanical ventilation | 7.10 | 2.96 | 17.3 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (per 1 mg/dL increase) | 1.46 | 1.28 | 1.66 | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (per 1 mg/dL increase) | 1.16 | 1.10 | 1.23 | <0.001 |

| Donor recipient gender mismatch | 2.20 | 1.27 | 3.79 | 0.004 |

| Simultaneous heart-kidney transplant | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.94 | 0.04 |

| Cumulative center volume<20 casesa | 1.74 | 1.07 | 2.84 | 0.03 |

| Duration between TAH-t implant and heart transplant | ||||

| <3 months | Ref | - | - | - |

| 3-6 months | 1.11 | 0.59 | 2.07 | 0.75 |

| >6 months | 1.16 | 0.55 | 2.44 | 0.70 |

| TAH-t implantation era | ||||

| 2010-2015 | Ref | - | - | - |

| 2016-2020 | 0.72 | 0.43 | 1.21 | 0.21 |

BMI: Body Mass Index; TAH-t: Total Artificial Heart

Cumulative center volume refers to the total volume of heart transplantation among TAH-t bridge to transplantation patients during the study period (2005-2020)

DISCUSSION

There are limited reports of outcomes after heart transplantation in patients bridged with TAH-t. In this context, our findings from the national UNOS data suggest that post-transplant survival after TAH-t BTT is acceptable although inferior to de novo heart transplant and durable LVAD BTT. Additionally, patients in the TAH-t BTT group who survive the early postoperative phase experience similar hazards of mortality over time compared to de novo transplant patients. Lastly, the extent of pre-transplant end-organ dysfunction and center experience were independent predictors of early post-transplant mortality.

The incidence of transplanting patients bridged with TAH-t has decreased in recent years. In 2020, only 6 cases were performed nationally, despite an overall increase in national heart transplant volume.11 This may represent more careful patient selection for TAH-t implantation and increasing use of temporary mechanical support devices to manage patients with biventricular failure. Revisions of the adult heart allocation policy in 2018 also likely played a role in the overall utilization of TAH-t. Under the revised policy, TAH-t patients are now listed as status 2, whereas patients with VA-ECMO and non-dischargeable biventricular assist devices (BiVAD) are listed as status 1. This may have resulted in more temporary mechanical circulatory support options being used to achieve a higher priority on the waitlist list and secure a suitable donor heart sooner.

We observed many differences in baseline recipient and donor characteristics. Notably, TAH-t BTT patients had worse renal dysfunction and a higher incidence of dialysis requirements after listing. These patients also had higher pre-transplant total bilirubin, likely a result of hemolysis. Importantly, patient selection for TAH-t implantation requires at least 10 cm distance between the posterior sternum and anterior spine at the level of T10, thus favoring males with larger body habitus. At the time of transplant, this likely results in matching these recipients to larger donors who were more likely to be male. Consequently, we observed that recipients in the TAH-t group were more likely to be male and had less sex mismatch.

Although patients undergoing heart transplantation after TAH-t implantation had unadjusted post-transplant outcomes that are inferior to de novo transplants and durable LVAD BTT, it is important to note that these patient populations have distinctively different underlying pathology and risk profiles. Therefore, it was not our intent to directly compare them, but rather to use the de novo transplant patients and durable LVAD BTT patients as points of reference. Patients undergoing heart transplantation after TAH-t bridging represents an extremely high-risk population, with significant multiple end-organ dysfunction before transplant despite the restoration of perfusion by TAH-t support. Recent single-center and multi-center studies have shown post-transplant survival ranging from 83% to 89% at 1 year and 75% to 79% at 5 years in TAH-t BTT patients.7,8 These numbers are better than what we had observed. One important distinction is that these studies were published by experienced centers, while our study was conducted using a national transplant registry, including 137 out of 392 patients (35%) who underwent transplantation at a center with less than 10 cumulative cases of experience. This highlights the importance of overall center experience in the care of these patients.

Consistent with prior findings from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) database, which established that the cumulative center volume of more than 10 cases of TAH-t implantation was a crucial determinant of success, we observed that the cumulative center volume ≥ 20 heart transplants involving TAH-t explantation was independently associated with improved 1-year post-transplant survival. Besides patient selection and management, this finding may reflect the importance of surgical experience. The explantation of TAH-t at the time of transplantation is technically challenging due to the formation of dense adhesions and constricted, inflamed pericardium. Strategies to minimize adhesion formation should be employed at the time of implantation, such as the use of polytetrafluoroethylene membrane to cover both the TAH-t device and vascular structures.12 Expeditious and safe dissection in TAH-t explantation can avoid the need for additional surgical repair of iatrogenic injuries, thereby reducing cardiopulmonary bypass time and minimizing donor organ ischemic time. The duration between TAH-t implant and heart transplant is also of consideration, as adhesions may worsen over time and result in more difficult dissections. Although previous studies found improved survival when heart transplant was performed between 3 and 6 months after TAH-t implantation,7,13 we did not observe such an association among the 292 patients with available TAH-t implant date (all of whom had TAH-t implantation after 2010).

In TAH-t BTT patients, we observed that the mortality risk during the first 12 months after transplant was significantly higher than patients who underwent de novo transplants. When survival to 1 year after transplant was achieved, these patients had subsequent survival comparable to de novo transplants. Additionally, multiorgan failure accounted for a quarter of the deaths during the first year after transplantation. These findings likely reflect the severity of their illness prior to transplantation. Although TAH-t implantation helps restore adequate systemic perfusion, recovery of end-organ function may be inadequate. In previous studies, 20% and 32% of patients did not show improvement in their liver and renal function, respectively, with 19–62% of patients being dialysis-dependent after TAH-t implantation.8,14,15 We also observed a 25% incidence of dialysis-dependent renal failure before transplant in TAH-t BTT patients. Additionally, markers of end-organ dysfunction such as baseline creatinine, total bilirubin, and the need for mechanical ventilation were all independent predictors of early mortality. Therefore, minimizing the extent of end-organ damage before transplant may be crucial in maximizing post-transplant survival. In this regard, exogenous BNP infusion has been shown to have a renal protective effect after TAH-t implantation in several small, single-arm studies.16-18 Simultaneous heart-kidney transplant was found to be independently associated with improved post-transplant survival in our study, although further research is warranted to determine the appropriateness of combined organ transplant in this high-risk population and which patient population supported by TAH-t would benefit the most from this approach.

Lastly, it is important to note that the current generation of TAH-t uses technology that dates back to the 1970s. Newer heart replacement devices with improved technology have been developed and some have entered in-human trials (NCT04117295).19 Additionally, the recent landmark achievement in xenotransplantation may also potentially alter the BTT approach in the future. Nevertheless, the knowledge and experience gained from the current SynCardia TAH-t will be crucial for the future management of patients with severe biventricular failure.

Limitation

This analysis of national post-transplantation outcomes of TAH-t BTT patients has several limitations. First, although we compared patients bridged to transplantation with TAH-t and those undergoing de novo heart transplantation and bridged to transplant with durable LVAD, these populations are distinctively different. It was not our intent to compare them but rather to use the de novo transplant and durable LVAD BTT patients as points of reference. We also considered a direct comparison to patients receiving BiVAD support. However, this was difficult as BiVAD supported patients represented a highly heterogeneous group in terms of device type and configuration. The use of a variety of paracorporeal and intracorporeal devices were reported, some implantations involved off-label use, and many patients received older generation devices that are no longer in use. Second, our analysis only reported post-transplant outcomes of TAH-t BTT patients, and patients who did not survive to transplant were not evaluated. However, post-implantation outcomes, including outcomes of patients who did not survive to transplantation, have been extensively described in previous analyses of multi-center and INTERMACS registry data.6,8 Third, besides patient survival, other long-term outcomes such as allograft rejection, cardiac allograft vasculopathy, and functional status were not assessed. Fourth, it is possible that perioperative stroke could be erroneously classified as post-operative stroke in the UNOS database, and the detailed timing of stroke events cannot be determined. Lastly, practice variation in surgical techniques and recipient/donor selection criteria could not be accounted for in our analysis.

CONCLUSION

Post-transplant survival after TAH-t bridging is acceptable although inferior to de novo heart transplant and durable LVAD BTT. However, when TAH-t BTT patients survived the early postoperative phase after heart transplantation, they had subsequent survival comparable to patients who underwent de novo transplants and those who were bridged to transplant with a durable LVAD. Careful patient selection for TAH-t implantation, maximizing end-organ recovery after TAH-t implantation, and increasing center experience may help improve post-transplantation outcomes in this critically ill population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

FUNDING

QC and AR are both supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health for advanced heart disease research (T32HL116273)

ABBREVIATIONS

- BiVAD

Bi-ventricular Assist Device

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- BTT

Bridge-to-Transplant

- TAH-t

Total Artificial Heart

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- IABP

Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- INTERMACS

Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- LVAD

Left Ventricular Assist Device

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- VA-ECMO

Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no relevant disclosures

DATA STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colvin M, Smith JM, Ahn Y, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2020 Annual Data Report: Heart. Am J Transplant. 2022;22 Suppl 2:350–437. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehra MR, Uriel N, Naka Y, et al. A Fully Magnetically Levitated Left Ventricular Assist Device - Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(17):1618–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehra MR, Naka Y, Uriel N, et al. A Fully Magnetically Levitated Circulatory Pump for Advanced Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):440–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copeland JG, Smith RG, Arabia FA, et al. Cardiac replacement with a total artificial heart as a bridge to transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):859–867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copeland JG, Smith RG, Arabia FA, et al. Cardiac replacement with a total artificial heart as a bridge to transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):859–867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arabía FA, Cantor RS, Koehl DA, et al. Interagency registry for mechanically assisted circulatory support report on the total artificial heart. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37(11):1304–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David CH, Lacoste P, Nanjaiah P, et al. A heart transplant after total artificial heart support: initial and long-term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;58(6):1175–1181. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrier M, Moriguchi J, Shah KB, et al. Outcomes after heart transplantation and total artificial heart implantation: A multicenter study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(3):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leppke S, Leighton T, Zaun D, et al. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: collecting, analyzing, and reporting data on transplantation in the United States. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2013;27(2):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kransdorf EP, Kittleson MM, Benck LR, et al. Predicted heart mass is the optimal metric for size match in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(2):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National data - OPTN. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/#

- 12.Copeland JG, Arabia FA, Smith RG, Covington D. Synthetic membrane neo-pericardium facilitates total artificial heart explantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20(6):654–656. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00248-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirsch M, Mazzucotelli JP, Roussel JC, et al. Survival after biventricular mechanical circulatory support: does the type of device matter? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(5):501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quader MA, Goodreau AM, Shah KB, et al. Renal Function Recovery with Total Artificial Heart Support. ASAIO J. 2016;62(1):87–91. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah KB. Renal function after implantation of the total artificial heart. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;9(2):124–125. doi: 10.21037/acs.2020.03.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado R, Wadia Y, Kar B, et al. Role of B-type natriuretic peptide and effect of nesiritide after total cardiac replacement with the AbioCor total artificial heart. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(8):1166–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah KB, Tang DG, Kasirajan V, Gunnerson KJ, Hess ML, Sica DA. Impact of low-dose B-type natriuretic peptide infusion on urine output after total artificial heart implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(6):670–672. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiliopoulos S, Guersoy D, Koerfer R, Tenderich G. B-type natriuretic peptide therapy in total artificial heart implantation: renal effects with early initiation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(6):662–663. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carmat SA. Carmat Total Artificial Heart Early Feasibility Study. clinicaltrials.gov; 2021. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04117295 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.