To the Editor:

Genomic profiling has allowed major advances in unraveling the complex molecular signature of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and has informed us of the prognosis and survival of AML patients [1, 2]. Advances in the biological understanding of AML pathogenesis have also led to the approval of new targeted agents that increase therapeutic options for treating AML [3, 4, 5]. In patients with good performance status newly diagnosed with AML and without co-morbidities intensive induction chemotherapy remains an option for achieving complete remission (CR)[3, 6].

The ability to predict responses to intensive induction chemotherapy could improve treatment decisions and patient care. Prediction at AML diagnosis that a patient would not respond to standard induction chemotherapy would lead to the use of other therapies sparing the patient from the toxicities of treatments that prove to be ineffective. Unfavorable risk cytogenetics, secondary or therapy-related AML, and specific gene mutations such as TP53 have been associated with low responses to intensive induction chemotherapy [7, 8]. Using next-generation sequencing (NGS), we first studied 34 genes to determine which molecular abnormalities relate to responses to intensive induction chemotherapy in newly diagnosed AML patients. We then used the pertinent molecular mutations to develop a model that predicts responses to induction chemotherapy.

Starting in 2016, the UPMC Hillman Cancer center started performing NGS sequencing for all newly diagnosed AML patients. At first, we used an external vendor (Onkosight myeloid panel by genpath) and in February of 2019 we transitioned to in-house NGS. FLT3-ITD mutations were identified on NGS using Pindel and ITDseek and the allelic ratio was verified using a PCR based method by first amplifying the juxtamembrane region and then sizing it on the ABI 3730 followed by Genescan analysis. We used the Medical Archival Retrieval System of the University of Pittsburgh [9] to review cases between June 2016 and January 2021 and identify newly diagnosed AML patients who had NGS analysis performed by genpath and the UPMC Pathology Department provided the list of the rest of the patients that had in-house NGS. Patients treated with induction chemotherapy at AML diagnosis were included in the analysis. All patients included in the study were treated with cytarabine (100 mg/m2/day/IV for 7 days) and idarubicin (12 mg/m2/day/IV days 1–3). Patients with persistent leukemia after the first course of chemotherapy were treated with a second course with mitoxantrone (10mg/m2/day/IV, days 1–5) and etoposide (100mg/m2/day/IV, days 1–5)[10]. FLT3+ patients received midostaurin with chemotherapy [11]. Prognostic factors at diagnosis were evaluated using the ELN genetic risk stratification [12] and response to therapy was evaluated using established criteria [12, 13].The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

The difference in distribution of each mutation between the patients who responded to induction chemotherapy and non-responders was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test and the Cochran-Armitage Trend test. Findings with an expected false discovery rate of ≤ 10% were reported as positive. Continuous factors were evaluated for association with the treatment group by the Kruskal-Wallis test which tested for any difference in mean value among the 3 groups (group 1: response after one course of induction chemotherapy; group 2: response after two courses; group 3: non-responders) and the Jonckheere-Terpstra test which is sensitive to an ordered difference among treatment groups.

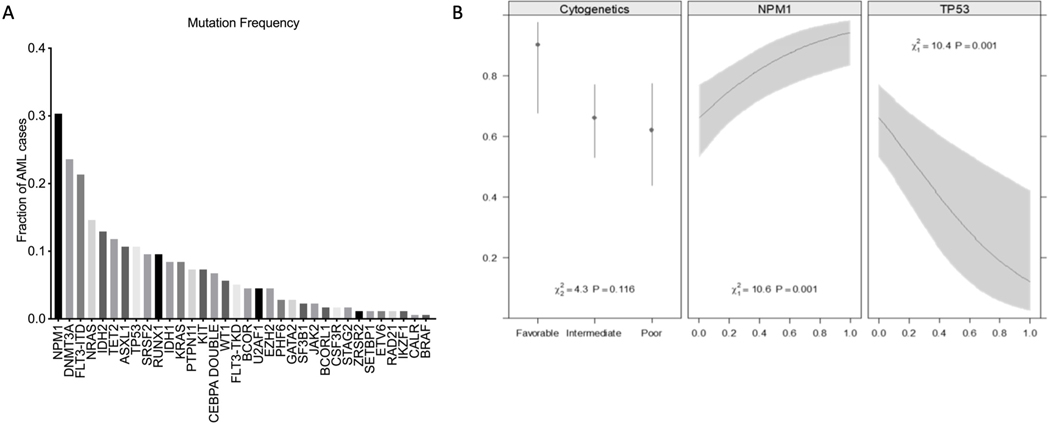

One hundred seventy-eight newly diagnosed AML patients (median age 60 years, range 46–66 years) were treated with intensive induction chemotherapy. Twenty patients (11%) had favorable risk cytogenetics, 108 patients (62%) had intermediate risk cytogenetics, and 47 patients (27%) had unfavorable risk cytogenetics. Supplemental Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included AML patients. Somatic alterations were identified in 99% of patients. The most common molecular event was an NPM1 (30.3%) mutation followed by DNMT3A (23.6%), FLT3-ITD (21.3%), NRAS (14.6%), TET2 (11.8%), ASXL1 (10.7%), and TP53 (10.7%) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 A. Somatic mutations of the entire cohort (n=178).

Among the genes, only NPM1, DNMT3A and TP53, were associated with response to intensive induction chemotherapy.

B. Probability to response to induction chemotherapy. NPM1, TP53, and cytogenetic class were used to fit a multivariate logistic model for response to the first course of chemotherapy. The presence of a TP53 mutation and poor cytogenetics, and the absence of an NPM1 mutation have a low probability of response to induction chemotherapy. The model is summarized by the C index (area under the ROC curve) and R2 (proportion of variance explained). After bootstrap validation, these statistics were reduced to 0.781 and 0.319, respectively.

One hundred forty-four of the 178 patients (81%) achieved CR after one or two courses of induction chemotherapy; one hundred twenty-five patients (70%) achieved CR after one course, and an additional 19 patients achieved CR after a second course. Thirty-four patients (19%) did not respond to one or two courses of induction chemotherapy. Measurable residual disease (MRD) data using multicolor flow cytometry were available in 93 (58%) patients that achieved CR; 34% of patients were MRD positive and 66% of patients were MRD negative following induction chemotherapy (Supplemental Table 2).

Among the 17 genes with at least 5% prevalence, only TP53, NPM1 and DNMT3A were associated with response to induction chemotherapy. AML in the setting of prior MDS/MPN or therapy-related AML and poor cytogenetics were associated with poor response (Supplemental Table 2). TP53 mutations increased monotonically with worse outcomes; TP53 mutations were present in only 1.6% of those responding to one course of chemotherapy, in 10.5% responding to two courses, and in 44.1% with no response to either course (p < 0.0001). Levels of variant allele frequency in the TP53 mutated patients did not predict response to induction chemotherapy (range, 8.4 – 89.1), although this analysis was limited by the small sample size. Eighty-nine percent of patients with TP53 mutations had poor cytogenetics. After induction chemotherapy, 15.8% of patients with TP53 mutations achieved CR and 5.3% achieved morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS). NPM1 mutations were associated with higher response rates to induction chemotherapy (p = 0.001). Ninety-six percent of patients with NPM1 mutations had intermediate cytogenetics. After induction chemotherapy, 92.6% of patients with NPM1 mutations achieved CR, 1.8% achieved CRi, and 1.8% achieved MLFS. The prevalence of a DNMT3A mutation was high in first and second course responders (28%, 26% respectively) but only 6% in non-responders. Eighty nine percent of patients with DNMT3A mutations had intermediate cytogenetics. After induction chemotherapy, 95.2% of patients with DNMT3A mutations achieved CR and 4.8% achieved CRi. From the laboratory values reported in Supplemental Table 1 only WBC was associated with response (p < .05).

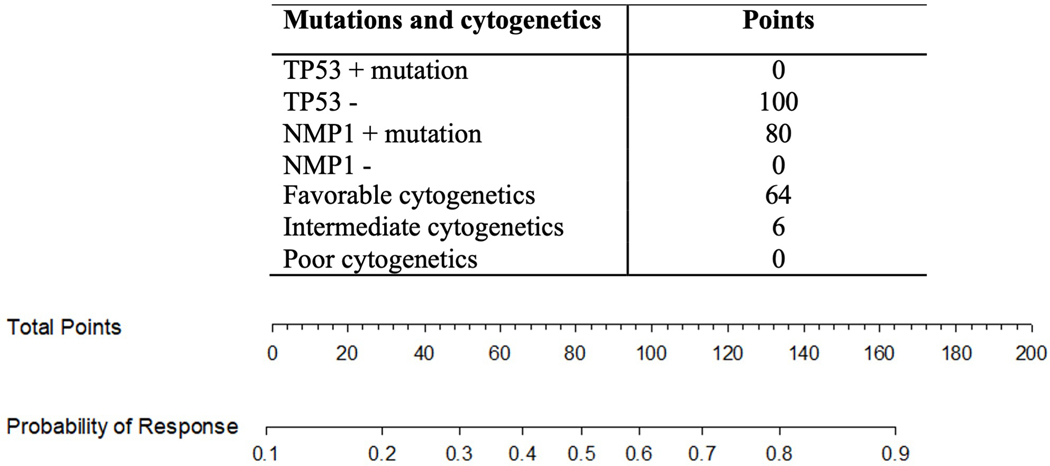

Based on findings that selected mutations, laboratory values and cytogenetic abnormalities were individually associated with response to induction chemotherapy, we used these covariates to develop a multivariate logistic model for predicting responses to first course induction chemotherapy. Multivariate model covariates were selected by Akaike’s Information Criteria to balance fit and complexity. Three covariates, NPM1, TP53 and cytogenetics were selected. Supplemental Table 3 details the regression coefficients for the final logistic model. Figure 1B illustrates the conditional effects these 3 predictors have on the probability to response to induction chemotherapy. Overfitting was quantified by estimating these summary statistics using cross-validation with bootstrap resampling (200 bootstrap reps). This model has a C index of 0.799 and an R2 0.378. To validate the model, bootstrap validation was performed with a C index of 0.781 and an R2 0.319 demonstrating that the model can predict responses to induction chemotherapy. To further illustrate the clinical utility of the prognostic model, a nomogram was developed that can be used to predict the probability of response to induction chemotherapy as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Nomogram that can predict response to induction chemotherapy.

The nomogram is used to assign points to each of the 3 predictors (TP53, NPM1, cytogenetics). The combined points for an individual patient are then added and the total points are compared to the probability for response to induction chemotherapy. For example, a patient with NPM1 mutation, intermediate cytogenetics and no TP53 mutation has a combined 186 points and a >0.9 probability of response.

Response rates in AML patients following induction chemotherapy with specific gene mutations have been previously reported. CR rates were improved with the use of high dose daunorubicin (90mg/m2) in newly diagnosed AML patients aged < 60 years with NPM1, DNMT3A or FLT-3 ITD mutations compared with standard dose daunorubicin (45mg/m2) [14]. Patients with SRSF2, U2AF1, ASXL1, EZH2, BCOR, and STAG2, and TP53 having therapy-related AML were significantly more likely to require multiple induction cycles than patients with de novo AML, suggesting relative chemoresistance in these groups [15]. NPM1 and CEBPA mutations were also associated with improved CR rates in patients that received intensive AML treatment compared to patients without these mutations [1].

Several groups have developed models with specific scores to predict responses to induction chemotherapy [16, 17, 18]. These used various categories of prognostic markers including clinical characteristics, laboratory values, cytogenetics, mutational status and gene expression. However, these models have not yet been widely adopted into clinical practice. In the current study, gene mutations were detected in almost all patients at AML diagnosis, results similar to other reports [1, 2]. Among the 17 genes we investigated, only mutations in TP53, NPM1 and DNMT3A were related to responses. Patients with TP53 mutations were associated with lower response rates to induction chemotherapy, whereas NPM1 and DNMT3A mutations were associated with improved responses. Bootstrap validation confirmed the reproducibility of our prognostic schema for predicting response to chemotherapy and a nomogram was created that can be used in clinical practice to predict responses to induction chemotherapy. The practical advantage of the nomogram is that it incorporates only the two relevant mutations that were associated with responses, TP53 and NPM1, and cytogenetic abnormalities to provide an accurate probability of response to induction chemotherapy.

Several limitations of this study warrant comment. Our results can only be applied to newly diagnosed AML patients treated with intensive induction chemotherapy. Performance status at AML diagnosis was not included in the model due to lack of data and factors influencing the decision-making regarding the use of induction therapy are not known. The goal of this work was to generate a predictive model and nomogram to induction chemotherapy. Whether the nomogram is also associated with overall survival was not investigated. Although bootstrap validation confirmed the reproducibility of our prognostic schema, he implementation of the proposed nomogram requires further validation in prospective clinical trials or the use of independent datasets.

To summarize, NGS has become essential in the treatment of AML. The mutations identified on NGS are necessary not only for the accurate risk classification of AML but for choosing the best treatment course for the patient. With this study we are highlighting that apart from predictive information in terms of relapse and need for allogeneic transplantation, the information from NGS can also be used to predict response to induction chemotherapy. This nomogram needs only three variables and thus it is very easy to remember and use. Using the nomogram, clinicians can guide discussions with patients that are at high risk of not responding to intensive induction chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

K.L. is supported by the NIH TL1 TR001858. The authors would like to thank Lois Malehorn for editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest disclosure:

Annie Im has performed consulting from Abbvie and CTI Biopharma and received research funding from Incyte. Alison Sehgal has received research funding from Kite/Gilead, Juno/BMS and Milltenyiz. Michael Boyiadzis is currently an adjunct professor of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and an employee of Genentech.

References

- 1.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016. Jun 9;374(23):2209–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel JP, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012. Mar 22;366(12):1079–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian H, Kadia T, DiNardo C, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia: current progress and future directions. Blood Cancer J. 2021. Feb 22;11(2):41. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00425-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estey E, Karp JE, Emadi A, et al. Recent drug approvals for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: gifts or a Trojan horse? Leukemia. 2020. Mar;34(3):671–681. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0704-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perl AE. The role of targeted therapy in the management of patients with AML. Blood Adv. 2017. Nov 14;1(24):2281–2294. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009829. advisory committee for Asana Biosciences and Actinium Pharmaceuticals and has consulted for Daiichi Sankyo, Astellas, Novartis, Pfizer, Arog, Seattle Genetics, Asana Biosciences, and Actinium Pharmaceuticals. Off-label drug use: This presentation includes novel agents in clinical development that do not yet have label indications in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The use of sorafenib, azacitidine, or decitabine for AML therapy is off label. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaelis LC. Cytotoxic therapy in acute myeloid leukemia: not quite dead yet. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018. Nov 30;2018(1):51–62. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.51. boards for Celgene, Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Incyte, has consulted for Celgene, and receives research funding from Jazz Pharmaceuticals. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Short NJ, Rytting ME, Cortes JE. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2018. Aug 18;392(10147):593–606. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roloff GW, Griffiths EA. When to obtain genomic data in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and which mutations matter. Blood Adv. 2018. Nov 13;2(21):3070–3080. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yount JR VJ CC. The Medical Archival System: an information-retrieval system based on distributed parallel processing. . Inf Process Manag 1991;27:379–89. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McHayleh W, Sehgal R, Redner RL, et al. Mitoxantrone and etoposide in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia with persistent leukemia after a course of therapy with cytarabine and idarubicin. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009. Nov;50(11):1848–53. doi: 10.3109/10428190903216788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, et al. Midostaurin plus Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia with a FLT3 Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017. Aug 3;377(5):454–464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017. Jan 26;129(4):424–447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003. Dec 15;21(24):4642–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luskin MR, Lee JW, Fernandez HF, et al. Benefit of high-dose daunorubicin in AML induction extends across cytogenetic and molecular groups. Blood. 2016. Mar 24;127(12):1551–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-657403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsley RC, Mar BG, Mazzola E, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations. Blood. 2015. Feb 26;125(9):1367–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-610543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herold T, Jurinovic V, Batcha AMN, et al. A 29-gene and cytogenetic score for the prediction of resistance to induction treatment in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2018. Mar;103(3):456–465. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.178442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter RB, Othus M, Burnett AK, et al. Resistance prediction in AML: analysis of 4601 patients from MRC/NCRI, HOVON/SAKK, SWOG and MD Anderson Cancer Center. Leukemia. 2015. Feb;29(2):312–20. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krug U, Rollig C, Koschmieder A, et al. Complete remission and early death after intensive chemotherapy in patients aged 60 years or older with acute myeloid leukaemia: a web-based application for prediction of outcomes. Lancet. 2010. Dec 11;376(9757):2000–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.