Abstract

Introduction:

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a common presentation for pediatric new-onset insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). Delayed diagnosis is the major risk factor for DKA at disease onset.

Methods:

Two pediatric endocrinologists independently reviewed the admission records to assess the appropriateness of pre-admission management at various health care settings before hospitalization.

Results:

Eighteen percent (n=45) of patients with new-onset IDDM had a delayed diagnosis. Twenty-eight were misdiagnosed (respiratory [n=9], non-specific [n=7], genitourinary [n=4], gastrointestinal [n=8] issues) and 17 were mismanaged. One child died within 4 hours of hospitalization, presumably due to hyperosmolar coma. Forty six percent (n=21) of patients with delayed diagnosis presented with DKA, comprising 18% of all DKA cases.

Conclusion:

A significant number of patients with new-onset IDDM were either misdiagnosed or mismanaged. All providers must be appropriately trained in diagnosing new-onset IDDM and follow the standard of clinical care practices when the diagnosis is reached for optimum outcomes.

Keywords: children, diabetes, incidence, diabetic ketoacidosis, misdiagnosis, mismanagement

1. Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most common chronic illnesses in pediatrics with an increasing incidence in the recent years, exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chao, Vidmar, & Georgia, 2021; Klingensmith et al., 2016; Lawrence et al., 2021; Nagl et al., 2022; Zylke & DeAngelis, 2007). An accurate and timely diagnosis is imperative to prevent acute complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). DKA at disease onset is estimated to be present in 15–67% of patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and 4–25% of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) (Dabelea et al., 2014; Wolfsdorf et al., 2018; Zeitler et al., 2018). Exact prevalence of HHS is not known due to its relative rarity. However, both of these complications are associated with increased morbidity and, although rare, mortality.

Although the common presenting symptoms of childhood diabetes (polyuria, polydipsia, nocturia, weight loss) still holds and manifests for up to several weeks in children with T1D, they could be indolent and non-specific particularly in patients with T2D. With the rise of obesity in children, the distinction between T1D and T2D can be more challenging (Stierman et al., 2021). Misdiagnosis or delayed referral are common and major risk factors for DKA at diagnosis (Rewers et al., 2008; Sundaram, Day, & Kirk, 2009; Wersäll, Adolfsson, Forsander, Ricksten, & Hanas, 2021). Most commonly misdiagnosed conditions include respiratory illnesses, gastrointestinal problems, urinary tract infections and other non-specified illnesses (Muñoz et al., 2019; Pawłowicz, Birkholz, Niedźwiecki, & Balcerska, 2009). Medical providers must be aware of the changing face of pediatric diabetes through education and awareness for timely diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment. A growing body of literature suggests that targeted awareness campaigns may allow for earlier diagnosis, thus reducing DKA at diagnosis. The aim of this study is to describe the characteristics of patients with new-onset insulin dependent diabetes (IDDM) requiring hospital admission, and analyze misdiagnosed and mismanaged cases in various health care settings before diabetes was diagnosed. As a secondary aim, we will compare the characteristics of the patients admitted in DKA or not.

2. Participants

Children and adolescents (< 18 years) admitted to the Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH) and Arkansas Children’s Northwest (ACNW) as new patients for the management of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2021, were included in this retrospective analysis. For this analysis IDDM collectively refers to all patients (T1D and T2D combined) who required insulin treatment for metabolic control on admission. Patients who did not require hospital admission, those with known T1D or T2D (i.e., diagnosed elsewhere), steroid-induced diabetes, and cystic-fibrosis related diabetes, and those with out-of-state zip code residential addresses were excluded from statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board.

3. Methods

Electronic medical records (EMR) were reviewed. Following data were collected on admission: Demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, zip code), health insurance status (public vs. private), weight, height, laboratory values (venous pH, serum glucose, beta-hydroxybutyrate, hemoglobin A1c, and pancreas auto-antibodies), and whether the patient received hypertonic saline or a head computed tomography for suspected cerebral edema, and finally, based on the caregiver’s report, whether the patient was seen by a health care provider (HCP) in the last thirty days before admission. Additionally, two pediatric endocrinologists independently reviewed the referral documents in EMR to verify caregivers’ reports, assess the appropriateness of pre-admission management, and determine whether there was a delay in the diagnosis or management of IDDM patients before hospital admission.

Inappropriate management was defined as i) inability to recognize new-onset diabetes (i.e., misdiagnosis) or ii) inaction or erroneous action (i.e., mismanagement) resulting in delayed delivery for appropriate care despite correctly diagnosing diabetes. Weight and height data used to calculate age and sex-specific body mass index (BMI) percentiles. Obesity defined as BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex. DKA was defined as venous pH < 7.30, and classified as mild (pH 7.20–7.29), moderate (pH 7.10–7.19), or severe (pH < 7.10). Diabetes type was determined based on auto-antibody (glutamic acid carboxylase-65 and islet antigen-2) results. Subjects with at least one positive pancreas auto-antibodies were classified as T1D. Residential zip codes were used to classify patients according to the health unit zones (Northwest, Northeast, Central, Southwest, Southeast) determined by Arkansas Department of Health.

4. Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and count (percentage) for categorical variables. Categorical proportions (e.g., sex, insurance status, etc.) were compared among groups using Fisher’s exact test. For a three-group comparison, one-way ANOVA was conducted, followed by all pairwise comparisons for post-hoc analysis. For a two-group comparison, Student’s t-test was used for variables that were normally distributed and a Mann-Whitney test for variables not normally distributed (as defined by p < 0.05, determined by Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test). A p-value < 0.05 considered significant. SPSS version 28 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, NY) was used for all calculations.

5. Results

5.1. Characteristics of patients with new-onset diabetes

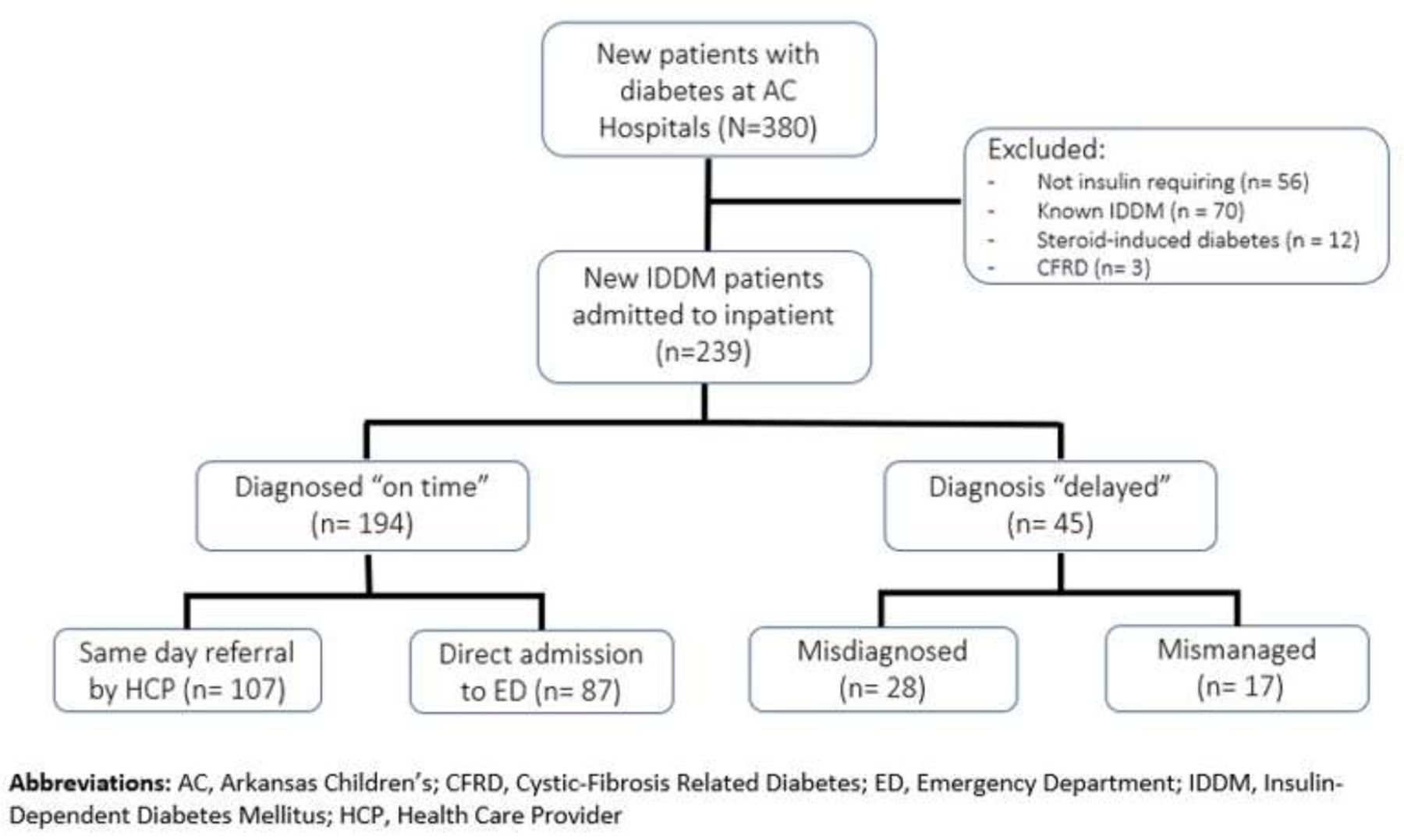

Three hundred eighty patients were diagnosed with new-onset diabetes in our centers in 2021. Of these, 141 were excluded from the final analysis: Fifty-six patients were managed in the outpatient setting and did not need insulin, seventy were previously diagnosed with IDDM elsewhere and already been on insulin treatment, twelve had steroid-induced diabetes, and three had cystic-fibrosis related diabetes. Our analysis included two hundred and thirty-nine children and adolescents with diabetes requiring hospital admission to initiate insulin treatment for the first time, including T1D and T2D (Figure 1). In our practice we admit all pediatric patients with presumed T1D to the hospital for intensive diabetes teaching, but admission for presumed T2D patients restricted to those with baseline HbA1c being ≥ 9 %.

Figure 1:

Consort flowchart of the study participants

Using the 2020 US census data, we calculated an approximate average annual incidence of 22.7 new cases of T1D per 100,000 children and 11.4 new cases of T2D per 100,000 children in Arkansas. Our findings for both T1D and T2D annual incidence rates are similar to that previously reported for five different geographical regions combined in the US (Lawrence et al., 2021; Mayer-Davis et al., 2017). As the state’s only pediatric hospital system, ACH and ACNW receive referrals from all over the state. Considering that some patients with T2D were managed as outpatient (i.e., HbA1c < 9 % at diagnosis), our calculated annual incidence rate for T2D is likely underestimated. Sixty-four percent of all patients (n=153) were evaluated by a health care provider (HCP) within the last 30 days preceding the diagnosis of new-onset IDDM, and one hundred-seven were referred to the nearest ED for further evaluation.

The average age of all patients was 11.7 years (ranging from 1 to 17 years). The study cohort was 46% female, 77% non-Hispanic white and 10% Hispanic, 61% had public insurance, 67% type 1 diabetes (T1D), and 38% obese. The average HbA1c of all patients was 11.8%. Twenty (8.4%) patients received a hypertonic solution or computed tomography of the head for suspected cerebral edema.

Overall, 194 patients (81.2%) were diagnosed “on time”, and forty-five (18.8%) had “delayed” diagnosis. Diagnosed on time group comprised of 107 same day-referred patients and eighty-seven who presented directly to the ED. Delayed diagnosis group subcategorized further into “delayed - misdiagnosed” (n = 28, 11.7%), and “delayed - mismanaged” (n = 17, 7.1%) subgroups. Three groups did not differ regarding the distribution of sex, race, ethnicity, insurance data, obesity status on admission, T1D percentage, mean HbA1c level, or health unit zones (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of all new onset insulin dependent diabetes mellitus patients, categorized based on timing of diagnosis (on time vs. delayed).

| All (n=239) | Diagnosed on time (n=194) | Delayed diagnosis (n=45) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Misdiagnosed (n=28) | Mismanaged (n=17) | ||||

| Age (year) at diagnosis | 11.7 ± 4.5 | 11.6 ± 4.5 a | 11 ± 5.1 a | 14.4 ± 2.9 b | 0.01 |

| Age Categories - 0 – 5 years - 6 – 12 years - 13 – 18 years |

38 (16%) 83 (35%) 118 (49%) |

32 (84%) 71 (85%) 91 (77%) |

6 (16%) 8 (10%) 14 (12%) |

0 4 (5%) 13 (11%) |

0.04 |

| Female sex | 110 (46%) | 89 (46%) | 12 (43%) | 9 (53%) | 0.80 |

| White race | 185 (77%) | 150 (77%) | 22 (78%) | 13 (77%) | 0.98 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 23 (10%) | 20 (10%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 0.75 |

| Public insurance | 146 (61%) | 120 (62%) | 15 (54%) | 11 (65%) | 0.67 |

| Type 1 Diabetes | 159 (67%) | 131 (68%) | 17 (61%) | 8 (47%) | 0.23 |

| Obese on admission | 91 (38%) | 71 (37%) | 11 (39%) | 9 (53%) | 0.41 |

| BMI status on Admission - Underweight - Normal - Overweight - Obese |

21 (9%) 100 (42%) 27 (11%) 91 (38%) |

19 (10%) 82 (42%) 22 (11%) 71 (37%) |

2 (7%) 11 (39%) 4 (14%) 11 (39%) |

0 7 (41%) 1 (6%) 9 (53%) |

0.72 |

| HbA1c on admission | 11.8 ± 1.9 | 11.9 ± 1.9 | 12.1 ± 1.9 | 11 ± 1.8 | 0.13 |

| pH | 7.25 ± 0.15 | 7.25 ± 0.15 a | 7.17 ± 0.17 a | 7.36 ± 0.04 b | <0.001 |

| Glucose | 432 ± 203 | 435 ± 193 a | 505 ± 261 a | 281 ± 125 b | 0.001 |

| BOHB | 4.4 ± 3.8 | 4.5 ± 3.8 a | 6.4 ± 3.6 b | 1.3 ± 1.7 c | <0.001 |

| DKA on admission | 117 (48%) | 96 (49%) a | 20 (71%) a | 1 (6%) b | <0.001 |

| Hypertonic solution on admission | 20 (8.4%) | 15 (8%) | 5 (18%) | 0 | 0.08 |

| CT Head on admission | 12 (5%) | 10 (5%) | 2 (7%) | 0 | 0.56 |

| County Zone - Northwest - Northeast - Central - Southwest - Southeast |

73 (30%) 28 (12%) 88 (37%) 33 (14%) 17 (7%) |

59 (30%) 21 (11%) 74 (38%) 28 (14%) 12 (6%) |

8 (29%) 4 (14%) 11 (39%) 4 (14%) 1 (4%) |

6 (35%) 3 (17%) 3 (18%) 1 (6%) 4 (24%) |

0.21 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), or actual numbers (percentages). Significant differences between groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc all-pairwise comparison. Labeled (a or b or c) means difference between groups following post-hoc analysis. Same letter indicates no difference between the groups compared. BOHB, Beta-hydroxybutyrate; CT, Computed tomography; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis

5.2. Cases with delayed diagnosis

Misdiagnosed cases (n=28, 11.1% of all cases) were assessed by an HCP for various symptoms in the last and diagnosed with diseases other than diabetes. These included non-specific or constitutional conditions (n = 7), respiratory illnesses (n = 9), gastrointestinal problems (n = 8), and genitourinary issues (n = 4). The average HbA1c of this group was 12.1%. Twenty (71%) patients in this group presented with DKA. Five (18%) patients received hypertonic saline infusion due to concerns for cerebral edema. Seventeen (61%) patients had T1D. Four subjects were prescribed steroid treatment 2–7 days before hospital admission for new-onset IDDM. One obese patient died four hours after presenting to the ED, presumably due to hyperosmolar hyperglycemic coma. Serum glucose level was > 1,600 mg/dL on admission and 1,140 mg/dL when death was announced. This subject was diagnosed with strep throat infection at a local urgent care facility two days before admission and given a dose of intramuscular penicillin and dexamethasone. This group’s median time between HCP evaluation and hospital admission was 4 days (range 1 – 29 days).

Mismanaged cases (n=17, 7.1% of total cases) were correctly diagnosed with diabetes, but the standard of care clinical guidelines was not followed for these patients, resulting in delayed management. In 12 patients, HCP opted to place an outpatient diabetes clinic referral while monitoring for worsening symptoms. In comparison, in 5 patients, HCP started oral medication and placed a referral. Three patients in the latter group were also given a prescription for basal insulin, but none of them started this treatment due to a lack of knowledge in insulin administration. The average HbA1c of this group was 11%. Only one patient in this group presented with DKA. Eight (47%) patients had T1D. This group’s median time between HCP evaluation and hospital admission was 13 days (range 2 – 30 days) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Characteristics of mismanaged patients

| ID | Sex | Race | Age (years) | HCP | Action taken by HCP | Time until admission (days) | DM Type | HbA1c (%) | DKA | BMI | Insurance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | M | W | 16 | PCP | Monitor for worsening of symptoms | 29 | 2 | 13.5 | No | Overweight | Public | |

| 21 | M | W | 17 | PCP | Endocrine outpatient referral | 22 | 2 | 11.5 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 40 | F | W | 12 | Urgent Care | Follow-up with PCP | 2 | 1 | 12.6 | No | Normal | Private | |

| 59 | M | W | 12 | PCP | Endocrine outpatient referral | 28 | 2 | 8.3 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 104 | F | B | 15 | PCP | Endocrine Outpatient Referral | 21 | 2 | 11.4 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 107 | F | W | 15 | PCP | Started Metformin. Endocrine outpatient referral | 25 | 2 | 10.8 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 110 | F | B | 15 | PCP | Endocrine outpatient referral | 30 | 2 | 9.7 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 185 | M | W | 17 | ED | Endocrine outpatient referral | 2 | 1 | 11 | No | Normal | Private | |

| 200 | M | B | 16 | PCP | Monitor for worsening of symptoms | 15 | 1 | 9.3 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 238 | F | B | 11 | PCP | Endocrine outpatient referral | 28 | 2 | 10.2 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 243 | F | W | 15 | PCP | Monitor for worsening of symptoms | 13 | 1 | 11.9 | No | Normal | Private | |

| 244 | F | W | 17 | PCP | Started Metformin. Endocrine outpatient referral | 7 | 2 | 13.1 | Yes | Normal | Public | |

| 255 | M | W | 13 | PCP | Recommended to start basal insulin. Endocrine outpatient referral. | 2 | 1 | 13.8 | No | Normal | Private | |

| 260 | M | W | 7 | PCP | Endocrine outpatient referral | 2 | 1 | 9.6 | No | Normal | Private | |

| 261 | F | W | 13 | PCP | Started metformin and recommended to start basal insulin. Endocrine outpatient referral | 2 | 2 | 10.2 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 269 | M | W | 13 | PCP | Recommended to start Started basal insulin. Endocrine outpatient referral. | 2 | 1 | 12.8 | No | Obese | Public | |

| 307 | F | W | 15 | PCP | Endocrine outpatient referral | 2 | 1 | 7.3 | No | Normal | Private | |

Abbreviations: B, Black; BMI, Body Mass Index, DKA, Diabetic Ketoacidosis; ED, Emergency Department; F, Female; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; M, Male, PCP, Primary Care Physician; W, White.

Compared to the mismanaged group, patients in the misdiagnosed group were younger (11 ± 5.1 vs. 14.4 ± 2.9 years, p = 0.02), had unfavorable serum markers on admission (lower pH, higher serum glucose and beta-hydroxybutyrate), and significantly higher risk of DKA on admission (Relative Risk 12.1, 95% CI 1.8, 82.4, p = 0.01). Groups did not differ in regards to demographics, HbA1c level on admission, and percentage of patients with T1D (61% vs. 47%, p=0.37). Median time between HCP evaluation and hospital admission was shorter in the misdiagnosed group (p = 0.01)

5.3. Diabetic Ketoacidosis on admission

Forty-nine percent (n = 117) of all patients presented with DKA. Compared to non-DKA group children with DKA were younger (11.1 ± 4.8 vs. 12.3 ± 4.2 years, p = 0.02) and they had higher HbA1c (12.4 ± 1.4 vs. 11.3 ± 2.2 %, p < 0.001) and serum glucose (522 ± 219 vs. 346 ± 141 mg/dL, p < 0.001) on admission. There were more male patients in this cohort (55% vs. 41% in females, p = 0.04). Race, ethnicity, insurance status, or residential zones were comparable between groups. DKA frequency was significantly higher in the 0–5 year age group (n = 26, 68%), compared to 6–12 year (n = 41, 49%) and 13–18 year (n = 50, 42%) groups (p = 0.02). There were more male patients with DKA than females in this cohort (55% vs. 41%, p = 0.04), and more patients with T1D (n = 90, 57%), compared to T2D (n = 27, 34%) (p < 0.001). Those with T1D had higher risk of DKA on admission compared to T2D patients requiring admission (Relative Risk 1.49, 95% CI 1.05–2.1, p = 0.02). DKA prevalence on admission was comparable between the “on time” and “delayed – misdiagnosed” groups, but were significantly higher compared to “delayed – mismanaged” group (44% vs. 71% vs. 6%, respectively, p < 0.001).

6. Discussion

This study evaluated data from 239 pediatric patients with new-onset IDDM (T1D and T2D combined). We assessed the appropriateness of pre-admission management of those evaluated by a health care provider (HCP) within 30 days before hospital admission. We found that 29% (45 out of 153) of patients assessed by an HCP were either misdiagnosed or mismanaged, leading to delayed delivery of appropriate care for diabetes and acute complications of diabetes (i.e., DKA). These cases comprised 19.6% (n = 21) of all DKA admissions and could have been prevented. Moreover, one patient died shortly after ED admission, presumably due to hyperosmolar hyperglycemic coma. He received a dose of intramuscular steroid treatment two days before presentation, possibly contributing to the severity of hyperglycemia and dehydration, exacerbating HHS.

We further showed that misdiagnosed cases were more likely to present with DKA at the onset of diabetes than those who were mismanaged. These two groups were comparable regarding the distribution of sex, race, ethnicity, type of diabetes, and obesity status suggesting that the diagnostic or management choices of the providers were not affected by patient characteristics. The American Diabetes Association guidelines for management of pediatric Type 2 DM recommend initiation of basal insulin in patients with HbA1c ≥ 8.5% (Arslanian et al., 2018). At our center, patients with HbA1c > 9% are generally admitted for basal/bolus insulin initiation education given that antibody testing for the type of diabetes is not quickly available and the diagnosis is sometimes not clear given the prevalence of obesity in the general population. Forty-seven percent of the mismanaged cases had T1DM and outpatient referral only delayed time to insulin initiation; fortunately, only one patient presented in DKA. All but two of the mismanaged patients had an HbA1c significantly greater than 9%. The patients who do not meet criteria for insulin initiation were not appropriately treated with metformin on a timely basis. As expected, the rate of DKA was higher in the misdiagnosed group given that the diagnosis of diabetes was not entertained and the symptoms were inappropriately treated with more significant delay in treatment.

Diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis is often the consequence of misdiagnosis or delayed treatment (Wolfsdorf et al., 2018). Many studies have examined the factors associated with diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adults with T1D. Usher-Smith et al. compiled data from more than 24,000 children from thirty-one countries. They showed that diagnostic error (i.e., misdiagnosis) and delayed treatment (i.e., mismanagement) along with younger age and lack of insurance coverage were associated with an increased risk of DKA (Usher-Smith, Thompson, Sharp, & Walter, 2011). Similarly, Munoz et al. surveyed the adult patients with T1D or the parents of children with T1D registered in the T1D Exchange clinic registry and online community. They found that about one-sixth of all children with T1D were initially misdiagnosed, with the rate of misdiagnosis being higher in the 0–6 year group (Muñoz et al., 2019). Flu/viral illnesses followed by non-specific conditions and bacterial infections were among the most commonly misdiagnosed conditions. In a retrospective analysis spanning over ten years in Malaysia, 38.7% of children with T1D were misdiagnosed and had a higher DKA admission rate than those diagnosed correctly (Mavinkurve et al., 2021). Another retrospective study from Poland showed a clinically significant delay in diagnosis of 14.1% of children (n = 67) with T1D, resulting in higher than average DKA admission rates in this population. Furthermore, most of the patients (79%) were evaluated by family physicians before T1D diagnosis was established (Pawłowicz et al., 2009).

Given that diagnostic errors and delayed treatment are major risk factors for pediatric DKA, campaigns have been carried out to increase awareness of pediatric diabetes in public and among medical providers with variable results. The “Parma” campaign in Italy, launched in the nineties, has shown a drastic decrease in DKA incidence at diabetes diagnosis (Cangelosi et al., 2017; Vanelli, Chiari, Lacava, & Iovane, 2007; Vanelli et al., 1999). Similar results were obtained in an awareness campaign in Australia that resulted in a 64% decrease in DKA rate at initial diagnosis (King et al., 2012). Both campaigns provided point-of-care pieces of equipment to check blood sugar and urine glucose or ketones at the doctor’s offices. On the contrary, no significant reduction in pediatric DKA rates were achieved in a Welch and Austrian study through informational posters only (Fritsch et al., 2013; Lansdown et al., 2012). These studies suggest that, in addition to increased awareness, empowering local providers with necessary tools such as point of care testing equipment is more likely to yield better results.

Despite increased alertness and ongoing efforts to reduce DKA rates among children with T1D, medical providers lack knowledge regarding presenting signs and symptoms in children with T2D, likely due to its gradual onset. In two previous studies conducted in Arkansas, authors demonstrated that up to 25% of youth with atypical diabetes had DKA at disease onset (Pihoker, Scott, Lensing, Cradock, & Smith, 1998; Scott, Smith, Cradock, & Pihoker, 1997). In our study, 33.7% (n = 27) of patients with T2D had DKA at diagnosis. Of these, eight were misdiagnosed, and one had delayed management as the cause of their DKA, which could have been prevented. Our results call for an urgent need to raise awareness among HCPs in our community regarding the frequency of IDDM being misdiagnosed as other illnesses and being mismanaged even when the diagnosis is correctly made, and that T2D patients are at risk for DKA like patients with T1D.

In conclusion, delayed diagnosis of pediatric IDDM due to misdiagnosed or mismanaged cases at various health care settings has led to an increased number of patients presenting with DKA at diabetes onset. Identifying knowledge gaps among the medical providers caring for children in these settings and providing periodic and targeted education for the initial diagnosis and management of IDDM may prevent future preventable errors. Considering the medical, psychosocial, economical, and medico-legal consequences of delayed management of pediatric diabetes, it is paramount importance to address the barriers through a concerted effort. Primary care services for children are being rendered by a variety of providers, including pediatricians, family practitioners, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or even internal medicine physicians. Given the heterogeneity of primary care providers, particularly in rural areas, educators in graduate schools should ensure the trainees are equipped with up-to-date knowledge, while medical and nursing societies as well as state boards ensure the currently practicing providers are aware and capable of implementing evidence-based pediatric diabetes guidelines involving diagnosis and initial management.

Highlights.

What is known?

Pediatric diabetes cases are on the rise.

Delayed diagnosis is the major risk factor for diabetic ketoacidosis.

What is new?

Diabetic ketoacidosis is a common presentation at diagnosis for children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Eighteen percent of children requiring hospital admission for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus had a delayed diagnosis due to missed diagnosis or mismanagement.

Targeted interventions are needed to empower community providers with the tools to diagnose pediatric diabetes, educate them about the acute consequences of delayed diagnosis and referral, and facilitate timely management.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to acknowledge the guidance provided during preparation of this manuscript made possible by the Center for Childhood Obesity Prevention funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM109096.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests: Authors have nothing to declare.

References

- Arslanian S, Bacha F, Grey M, Marcus MD, White NH, & Zeitler P (2018). Evaluation and management of youth-onset type 2 diabetes: A position statement by the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care 10.2337/dci18-0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi AM, Bonacini I, Pia Serra R, Di Mauro D, Iovane B, Fainardi V, … Vanelli M (2017). Spontaneous dissemination of DKA prevention campaign successfully launched in Nineties in Parma’s province. Acta Biomedica 10.23750/ABM.V88I2.6553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao LC, Vidmar AP, & Georgia S (2021). Spike in diabetic ketoacidosis rates in pediatric type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Care 10.2337/dc20-2733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabelea D, Rewers A, Stafford JM, Standiford DA, Lawrence JM, Saydah S, … Pihoker C (2014). Trends in the prevalence of ketoacidosis at diabetes diagnosis: The search for diabetes in youth study. Pediatrics 10.1542/peds.2013-2795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch M, Schober E, Rami-Merhar B, Hofer S, Fröhlich-Reiterer E, & Waldhoer T (2013). Diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis in Austrian children: A population-based analysis, 1989–2011. Journal of Pediatrics 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BR, Howard NJ, Verge CF, Jack MM, Govind N, Jameson K, … Bandara DWS (2012). A diabetes awareness campaign prevents diabetic ketoacidosis in children at their initial presentation with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingensmith GJ, Connor CG, Ruedy KJ, Beck RW, Kollman C, Haro H, … Tamborlane WV (2016). Presentation of youth with type 2 diabetes in the Pediatric Diabetes Consortium. Pediatric Diabetes 10.1111/pedi.12281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown AJ, Barton J, Warner J, Williams D, Gregory JW, Harvey JN, & Lowes L (2012). Prevalence of ketoacidosis at diagnosis of childhood onset Type 1 diabetes in Wales from 1991 to 2009 and effect of a publicity campaign. Diabetic Medicine 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JM, Divers J, Isom S, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Pihoker C, … Liese AD (2021). Trends in Prevalence of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents in the US, 2001–2017. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 10.1001/jama.2021.11165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavinkurve M, Jalaludin MY, Chan EWL, Noordin M, Samingan N, Leong A, & Zaini AA (2021). Is Misdiagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Malaysian Children a Common Phenomenon? Frontiers in Endocrinology 10.3389/fendo.2021.606018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, Dolan L, … Wagenknecht L (2017). Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002–2012. New England Journal of Medicine 10.1056/nejmoa1610187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz C, Floreen A, Garey C, Karlya T, Jelley D, Alonso GT, & McAuliffe-Fogarty A (2019). Misdiagnosis and Diabetic Ketoacidosis at Diagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes: Patient and Caregiver Perspectives. Clinical Diabetes 10.2337/cd18-0088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagl K, Waldhör T, Hofer SE, Fritsch M, Meraner D, Prchla C, … Fröhlich-Reiterer E (2022). Alarming Increase of Ketoacidosis Prevalence at Type 1 Diabetes-Onset in Austria—Results From a Nationwide Registry. Frontiers in Pediatrics 10.3389/fped.2022.820156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawłowicz M, Birkholz D, Niedźwiecki M, & Balcerska A (2009). Difficulties or mistakes in diagnosing type 1 diabetes in children? - demographic factors influencing delayed diagnosis. Pediatric Diabetes 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihoker C, Scott CR, Lensing SY, Cradock MM, & Smith J (1998). Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in African-American youths of Arkansas. Clinical Pediatrics 10.1177/000992289803700206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewers A, Klingensmith G, Davis C, Petitti DB, Pihoker C, Rodriguez B, … Dabelea D (2008). Presence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in youth: The search for diabetes in youth study. Pediatrics 10.1542/peds.2007-1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CR, Smith JM, Cradock MM, & Pihoker C (1997). Characteristics of youth-onset noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus at diagnosis. Pediatrics 10.1542/peds.100.1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll MD, Chen TC, Davy O, Fink S, … Akinbami LJ (2021). National health and nutrition examination survey 2017–march 2020 prepandemic data files-development of files and prevalence estimates for selected health outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports 10.15620/cdc:106273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram PCB, Day E, & Kirk JMW (2009). Delayed diagnosis in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Archives of Disease in Childhood 10.1136/adc.2007.133405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher-Smith JA, Thompson MJ, Sharp SJ, & Walter FM (2011). Factors associated with the presence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of diabetes in children and young adults: A systematic review. BMJ 10.1136/bmj.d4092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanelli M, Chiari G, Lacava S, & Iovane B (2007). Campaign for diabetic ketoacidosis prevention still effective 8 years later [2]. Diabetes Care 10.2337/dc07-0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanelli M, Costi G, Chiari G, Giacalone T, Ghizzoni L, & Chiarelli F (1999). Effectiveness of a prevention program for diabetic ketoacidosis in children: An 8-year study in schools and private practices. Diabetes Care 10.2337/diacare.22.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersäll JH, Adolfsson P, Forsander G, Ricksten SE, & Hanas R (2021). Delayed referral is common even when new-onset diabetes is suspected in children. A Swedish prospective observational study of diabetic ketoacidosis at onset of Type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes 10.1111/pedi.13229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsdorf JI, Glaser N, Agus M, Fritsch M, Hanas R, Rewers A, … Codner E (2018). ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatric Diabetes 10.1111/pedi.12701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitler P, Arslanian S, Fu J, Pinhas-Hamiel O, Reinehr T, Tandon N, … Maahs DM (2018). ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Type 2 diabetes mellitus in youth. Pediatric Diabetes 10.1111/pedi.12719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylke JW, & DeAngelis CD (2007). Pediatric chronic diseases - Stealing childhood. Journal of the American Medical Association 10.1001/jama.297.24.2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]