Abstract

Arrestins are important scaffolding proteins that are expressed in all vertebrate animals. They regulate cell signaling events upon binding to active G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) and trigger endocytosis of active GPCRs. While many of the functional sites on arrestins have been characterized, the question of how these sites interact is unanswered. We used anisotropic network modelling (ANM) together with our covariance compliment techniques to survey all the available structures of the non-visual arrestins to map how structural changes and protein-binding affect their structural dynamics. We found that activation and clathrin binding have a marked effect on arrestin dynamics, and that these dynamics changes are localized to a small number of distant functional sites. These sites include α-helix 1, the lariat loop, nuclear localization domain, and the C-domain β-sheets on the C-loop side. Our techniques suggest that clathrin binding and/or GPCR activation of arrestin perturb the dynamics of these sites independent of structural changes.

Keywords: Anisotropic network modelling, arrestin, allostery, GPCR

2. Introduction

The arrestin family of proteins has four members: the visual arrestins arrestin-1 and arrestin-4, and the visual arrestins arrestin-2 and arrestin-3, also called β-arrestins 1 and 2 [1, 2]. The first role identified for arrestins was the regulation of G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) activity by triggering receptor endocytosis and recycling.[1, 2] More recent work has shown that non-visual arrestins also activate cell signaling proteins, [1, 2] including kinases such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK). As such, arrestins are a second branch of GPCR signaling pathways that complement the primary G-protein pathway [3–7].

Arrestins are recruited to activated GPCRs after G-protein coupled receptor kinases (GRK) have phosphorylated the C-terminal tail of the GPCR [8], which triggers arrestin binding and activation. Upon activation, arrestin recruits clathrin and adaptin, which in turn causes endocytosis of both the GPCR and arrestin [9–12]. Arrestin will then sort the bound GPCR into either a degradation or recycling pathway [13]. Afterwards, arrestin is translocated to the nucleus, where it alters gene transcription [14]. The identity of the GPCR and the pattern of phosphorylation determines which of its downstream partners arrestin recruits [8, 15]. These factors control whether the GPCR is recycled or degraded, the specific kinases arrestin recruits, and which downstream effectors are triggered [8, 16–20]. The mechanism by which this process occurs remain elusive. We hypothesize that allosteric coupling of specific functional sites on arrestin convey the information about arrestin’s current binding partners and hence its final destiny in the cell.

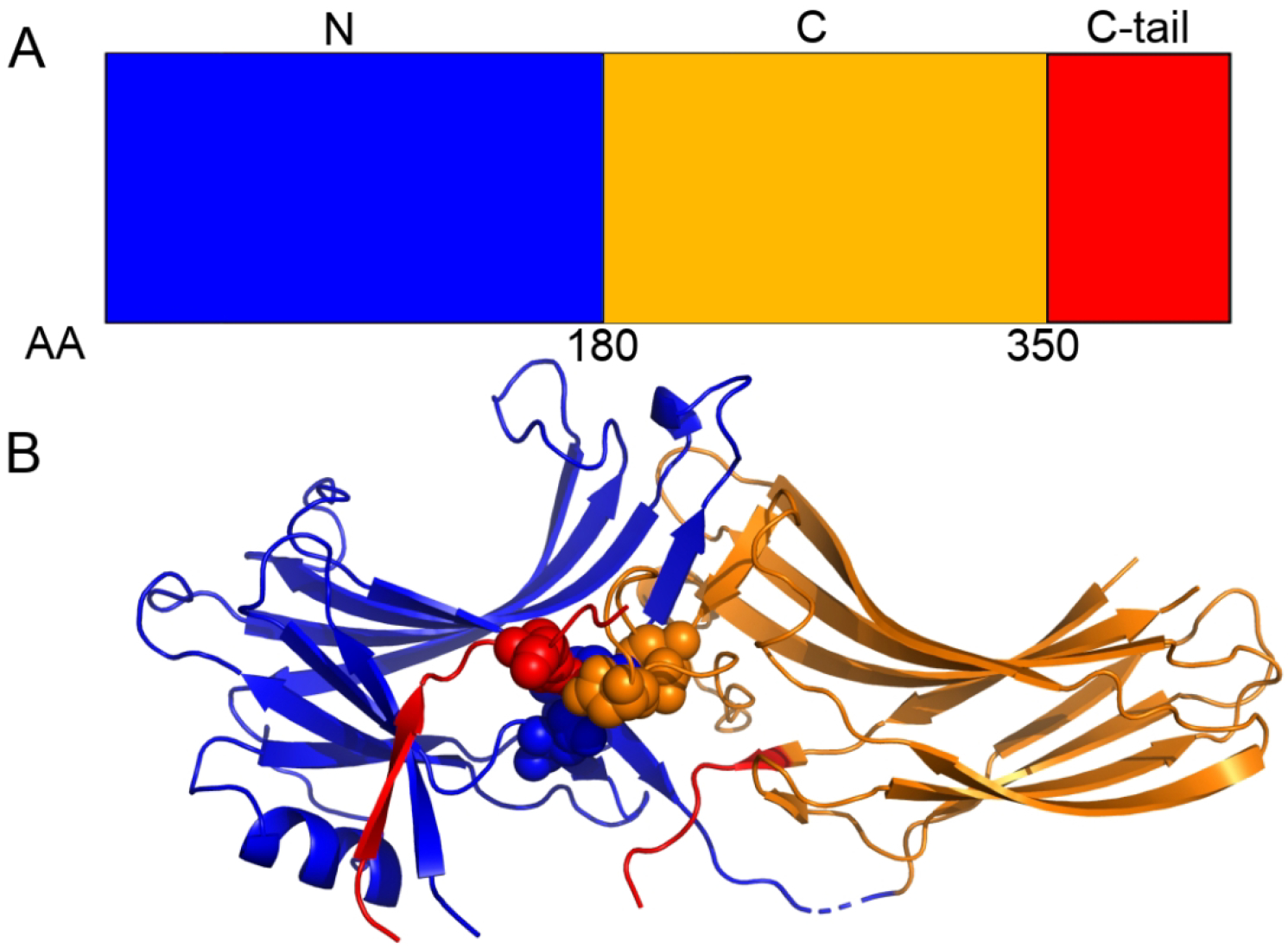

All arrestin proteins consist of three distinct structural domains (Figure 1) [13]: the N-domain, the C-domain, and the C-tail. The N-domain is the N-terminal portion of the protein and consists of the GPCR binding site, α-helix 1, and residues D26 and R169 of the polar core [13, 21–23]. The C-domain forms the other structured portion of arrestin; this domain contains a pair of β-sheets, the C-loops, the Lariat loop, and residues D290 and D297 of the polar core [23]. The C-tail is a long unstructured loop that binds to the N-domain when arrestin is inactive; it contains residue R393 of the polar core and the clathrin binding site [13, 23]. The polar core of arrestin (residues D26, R169, D290, D297, and R393 in arrestin-2) is responsible for keeping it inactive when not bound to a GPCR. When arrestin binds a GPCR, the GPCR’s C-terminal tail displaces arrestin’s C-tail domain and the phospho-residues disrupt the charge balance of the polar core, allowing for activation (Figure 2)[24–26]. Upon arrestin activation, α-helix 1 stabilizes GPCR binding to arrestin without changing its position with respect to the rest of the N-domain [22], and the C-loops in the C-domain stabilize membrane binding [9, 10, 27] (Figure 2); this region is also responsible for binding clathrin. This leads to an interesting question: how do α-helix 1 and the C-loops stabilize binding of their respective partners only when arrestin is in the active form even though their structures are essentially identical in both states? Despite the wealth of crystallographic data, many questions remain about arrestin structure/function relationships.

Figure 1:

The A) domain and B) crystallography structure of Arrestin-2. The N-domain (blue), C-domain (orange), and C-tail domain (red) are shown along with the polar core domain (spheres). The discontinuity in the red backbone exists because a ~35-residue region of the C-tail domain is missing from all crystal structures.

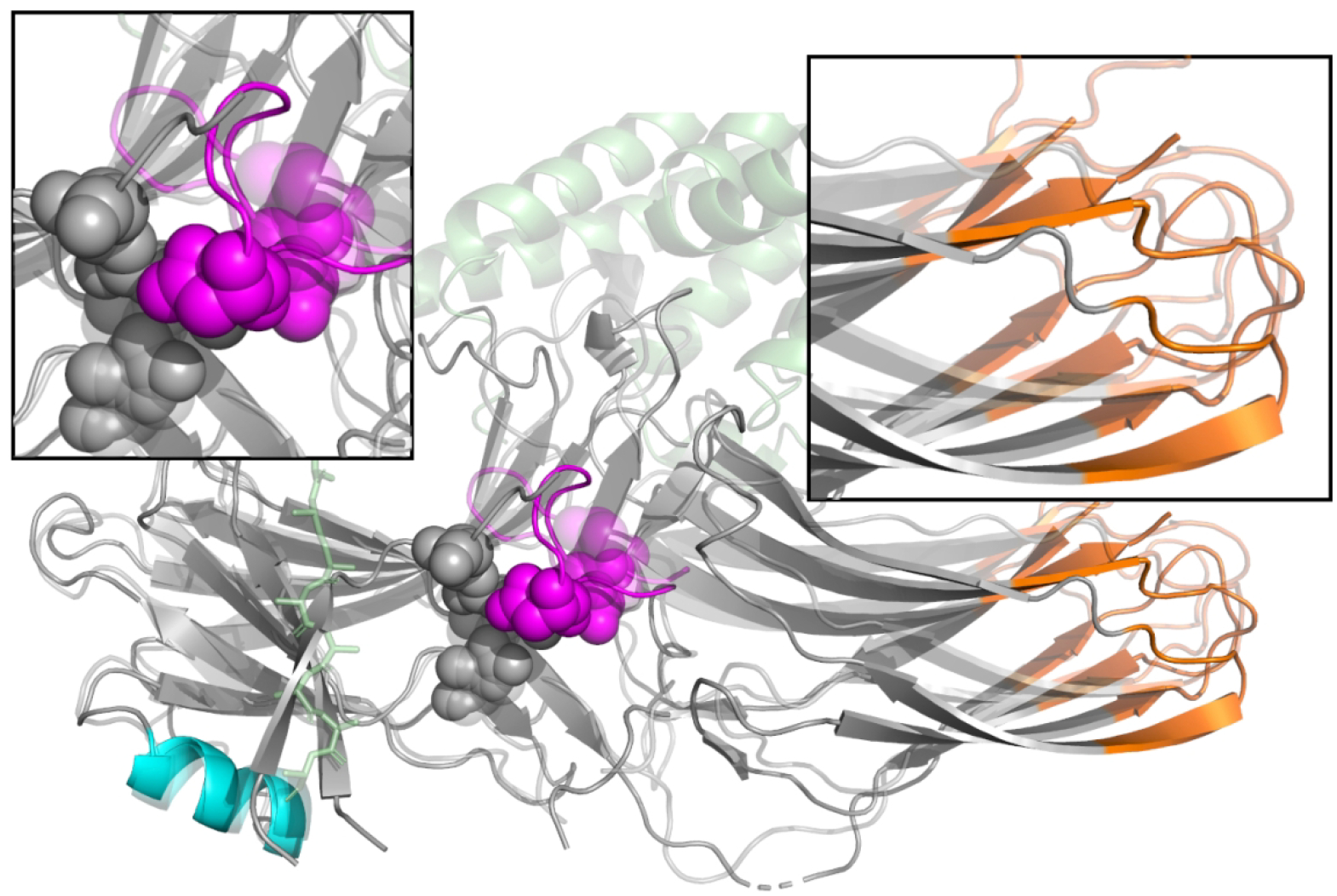

Figure 2:

Changes in the structure of arrestin upon activation. Inactive arrestin (solid) and active arrestin (translucent) are superimposed on touch of each other, with the N-terminal domain on the left as in Figure 1. The polar core (spheres), lariat loop (purple), GPCR (green), and GPCR C-terminal peptide (green sticks) are shown. Blue and purple regions represent sequence which is included in our ANM modelling. Arrestin activation is marked by the disruption of the polar core residues (top left panel), and a rotation of the C-domain with respect to the N-domain (top right panel).

Elastic network models, specifically the anisotropic network model (ANM), are a valuable tool for rapidly probing large-scale motions of proteins[28–31]. In contrast to all-atom molecular dynamics simulations, which require a complex force field with many parameters and computationally expensive sampling[32], ANM uses a simple harmonic model of protein motions, where neighboring residues interact using simple springs. The fluctuations of the system are then obtained using an eigenvalue decomposition[28]. The resulting calculation is computationally efficient enough to be applied in an informatics setting, surveying all structures in a family [31]. Despite its simplicity, predictions from the low-frequency, or high-amplitude, modes agree well with the dominant modes of principal component analysis of all-atom molecular dynamics simulations and with hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HX-MS) [30, 33–35].

Here we report that α-helix 1, the C-domain β-sheets on the C-loop side, the center of the lariat loop, and the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) alter their dynamic motions based on arrestin’s current state and binding partners. This provides a mechanism for how arrestin’s function changes during its activation and sorting process.

3. Methods

3.1. X-ray Structure Selection and Analysis

Crystallographic data were obtained from the Protein Data Bank [36, 37]. All apo, peptide-bound, and GPCR-bound X-ray structures of arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 were initially selected. If multiple protein chains were resolved in a single asymmetric unit, we separated these structures and analyzed them separately; these structures are denoted by their PDB id code with a (b) afterwards. Sequences and structures of these proteins were aligned and unresolved regions in the structures were identified. Two structures (3GC3, 6KL7(b)) were excluded from analysis because too many residues were not resolved. We identified the regions that were present in all structures and focused our analysis on that core, while removing any regions that appeared unstructured. The remaining consensus sequence was then analyzed. Table S1 shows the aligned sequences of all structures used in this study. Regions of removed sequence as well as any other resolved proteins or peptides were implicitly included in our model by means of vibrational subsystem analysis (VSA) [38]. Any stabilizing antibody chains resolved in the structure were not included in the calculations.

We analyzed a total 26 X-ray structures, where 19 were arrestin-2 and 7 were arrestin-3. Of these, 9 were apo structures, 1 was clathrin-bound, 2 were inositol-6-phosphate (IP6) activated structures, 4 were GPCR-activated arrestin structures, and 10 were peptide-activated (Table 1) [39–51]. ANM was then performed using the alpha carbons of all 26 structures using VSA to model in all removed sequences, and the resulting eigenvalues and eigenvectors were saved, resulting in our final data set.

Table 1:

Arrestin Structures

| PDB ID | PMID | Arrestin | Species | Type | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3P2D | 21215759 | 3 | Bos taurus | Apo | Inactive |

| 1G4R | 11566136 | 2 | Bos taurus | Apo | Inactive |

| 2WTR | 2 | Bos taurus | Apo | Inactive | |

| 6KL7 | 31948726 | 2 | Rattus norvegicus | Apo | Inactive |

| 1G4M | 11566136 | 2 | Bos taurus | Apo | Inactive |

| 1JSY | 11876640 | 2 | Bos taurus | Apo | Inactive |

| 3GD1 | 19710023 | 2 | Bos taurus | Clathrin-Bound | Inactive |

| 1ZSH | 16439357 | 2 | Bos taurus | IP6 | Inactive |

| 5TV1 | 29127291 | 3 | Bos taurus | IP6 | Active |

| 6UP7 | 31945771 | 2 | Homo sapiens | GPCR-bound | Active |

| 6U1N | 31945772 | 2 | Homo sapiens | GPCR-bound | Active |

| 6TKO | 32555462 | 2 | Homo sapiens | GPCR-bound | Active |

| 6PWC | 31776446 | 2 | Homo sapiens | GPCR-bound | Active |

| 6NI2 | 31740855 | 2 | Bos taurus | Vasopressin-Bound | Active |

| 4JQI | 23604254 | 2 | Rattus norvegicus | Vasopressin-Bound | Active |

| 7DF9 | 33888704 | 2 | Bos taurus | Vasopressin-Bound | Active |

| 7DFA | 33888704 | 2 | Bos taurus | Vasopressin-Bound | Active |

| 7DFB | 33888704 | 2 | Bos taurus | Vasopressin-Bound | Active |

| 7DFC | 33888704 | 2 | Bos taurus | Vasopressin-Bound | Active |

| 6K3F | 32579945 | 3 | Rattus norvegicus | CXCR7-Bound | Active |

3.2. Anisotropic Network Modeling

ANM models the protein as a network of beads connected by springs, with each bead representing the position of a Cα atom. The potential energy between the ith and jth Cα in the network is given by Hooke’s Law:

| (1) |

where is the distance between the ith and jth Cα atom in the reference structure, γ is the spring constant term, and Γij is the connectivity term [28, 30, 52]. As a result, in this formalism the reference structure is the global minimum energy state. The results are independent of the precise value for the spring constant γ, so we arbitrarily define it to be 1 N/Å, while the connectivity term is defined as:

| (2) |

| (3) |

This creates a 3N × 3N Hessian matrix, where N is the number of nodes in the network (Cα atom in the structure). When diagonalized, the matrix returns eigenvalues (λi) and eigenvectors corresponding to the vibrational modes of the protein. The cutoff of 15 Å is the standard cutoff used for ANM as formalized by Bahar et. al. [28]; varying the cutoff will only have subtle effects on the resulting eigendecomposition[34]. The eigenvectors are the directions of motion, with each associated eigenvalue corresponding to the frequency of that motion. In ANM, the frequency-squared of motion is inversely proportional to the amplitude of motion, due to the model’s harmonic nature. This means that the lowest frequency modes represent the highest amplitude motions. The 6 zero frequency modes corresponding to rigid body translation and rotation are ignored for all subsequent analysis.

The various structures used in our model had different numbers of Cα atoms, but the resulting eigendecompositions can only be easily compared when the matrix dimensions are identical. We managed this challenge using VSA [29, 31, 38] as implemented in LOOS [29, 53]. This method partitions the Hessian matrix into an environment and a subsystem, where the subsystem contains all consensus residues; these are the amino acids for which the vibrational motions are computed. The remaining residues are part of the environment, and their effects on the subsystem are included implicitly. This approach allows us to use a common set of atoms for all proteins, which facilitates direct comparison, while still including the rest of the resolved structure.

3.2. Covariance complement

We compared our ANM eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the various arrestins to each other using a modified version of covariance overlap, called covariance complement [30, 31, 54].

| (4) |

Where and are the ith eigenvalue and eigenvector of structure A, and and are the jth eigenvalue and eigenvector of structure B. The covariance complement is 0 when the two ANM eigensets are identical and 1 when they are completely orthogonal. The primary advantage of using the covariance overlap or complement is that they compare the entire eigenset rather than an arbitrarily chosen subset, and that they account for the relative amplitudes of the motions rather than just the directions.

3.3. Per-Residue Contribution to Dot Product

We compared the low modes of our ANM eigenvectors to determine how much each residue contributes to the overall difference to the total dot product. We define this as a vector where each residue r consists of a 3-dimension sub-vector taken from the eigenvector used in equation 4. This represents the 3-dimensional motions of each individual residue as defined by the eigenvector. We then compute a difference score by:

| (5) |

where is the (x,y,z) components of a specific eigenvector corresponding to the motions of the ith residue of structure A and is the equivalent from structure B. Since the original eigenvector has already been normalized, the sum of the dot product of all residues, and residues We then computed the average by averaging over all possible combinations of structures A and B and present the data in arbitrary units based on the contribution.

4. Results

4.1. Structures and Dynamics Comparison

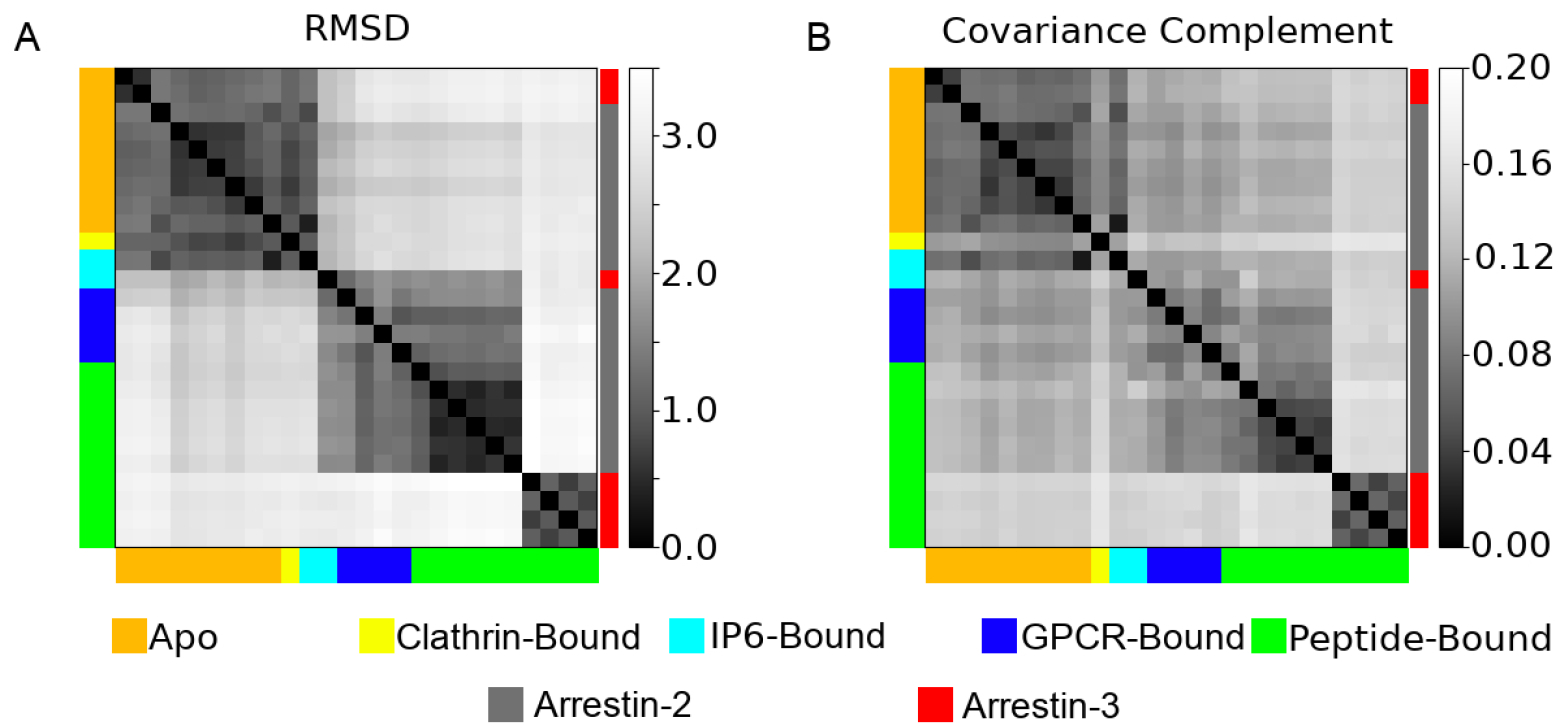

There are several crystallographic structures of both arrestin-2 and arrestin-3. These structures include apo arrestin [40, 44, 47, 50, 51], as well as arrestin bound to clathrin [43], IP6 [39, 46], activating peptides [41, 55, 56], and GPCRs [42, 48, 49]. They form three distinct structural clusters, as shown by Figure 3: an apo cluster with the C-tail domain bound to the N-domain, and two distinct active conformations representing the C-tail unbinding and the N-domain and C-domain rotating with respect to each other. Arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 form two distinct structures that differ mainly by the degree of rotation between the N-domain and C-domains [39].

Figure 3:

A pairwise comparison of the A) root mean squared deviation (RMSD) and B) the covariance complement derived from the 26 different structures analyzed in this study. Structures are color coded both by their ligands (left and bottom of graph), or whether they are arrestin-2 (gray) or arrestin-3 (red) (right of graph).

We analyzed 26 protein chains from 20 distinct crystal structures (Table 1); Figure 2 shows their common structural elements. Their structures were compared using the standard alpha-carbon root mean square deviation (RMSD) after alignment. The covariance complement (Eq 4) was used to quantify the differences in their fluctuations, as estimated using VSA; the results are shown as Figure 3. As these structures originate from a variety of species (Homo sapiens, Bos taurus, etc.) and two different subtypes of arrestin, we first examined their sequence homology (Figure S1). These structures show high sequence homology when comparing structures of the same sub-type. All arrestin-2 structures have an average homology of 99.1%, and all arrestin-3 structures have an average homology of 97.9%. The average homology between all arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 structures was 77.0%.

All analyzed arrestin structures are quite similar, with a maximum pairwise RMSD of 3.46 Å and covariance complement of 0.149. That said, the structures form some distinct clusters readily visible in the heatmaps. All apo arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 structures are extremely similar with a maximum pairwise RMSD of 0.95 Å. This similarity exists despite sharing only 77.0% sequence homology. The apo cluster also contains the clathrin-bound structure, 3GD1, and one of the IP6-bound structures, 1ZSH. The GPCR-bound and peptide-bound arrestin structures form 2 distinct clusters. The first contains the arrestin-2 structures and the other IP6-bound structure, 5TV1, while the second contains the arrestin-3 structures (Figure 3A). The main difference between these clusters is the degree of rotation between the N-domain and the C-domain.

Focusing on the protein fluctuations (Figure 3B) tells a subtly different story. The apo structures and peptide-bound arrestin-3 structure fluctuations form two clusters corresponding to those seen in the structural analysis. However, the single clathrin-bound structure has dynamics that place it essentially in a cluster by itself, despite its structural similarity to the apo proteins. The vasopressin-bound arrestin-2 structures (6U1N, 6NI2, 4JQI, 7DF9, 7DFA, 7DFB, 7DFC), which structurally clustered with the other peptide-bound and GPCR-bound chains, form their own distinct cluster from a dynamics perspective. The remaining arrestin-2 chains and the other IP6-bound chain appear to be as dissimilar from each other as they are from the apo structures (Figure 3B). From this, we conclude activated arrestins have similar structures but unique dynamics that are determined by the peptide they are bound to.

The differences in dynamics observed upon activation cannot be explained by differences in protein sequence due to arrestin structures coming from different species (Table 1). This can be seen by examining the GPCR-bound structures in Figure 3B and observing that their dynamics is as dissimilar from each other as they are from the apo arrestin structures. This is in spite of the fact that each of these structures is from the same species (Homo Sapiens).

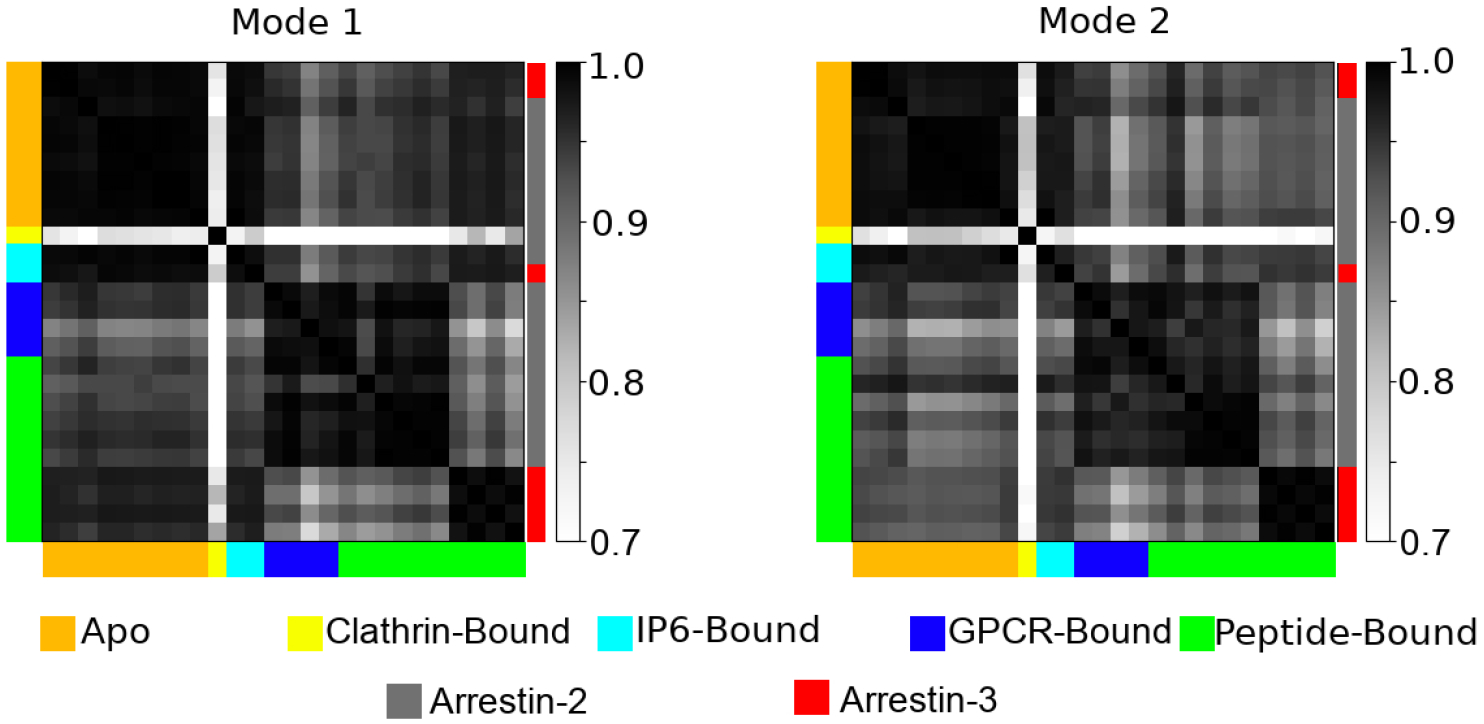

4.2. Comparison of Modes of Motion

We did a mode-wise comparison of the various eigensets and discovered that the first two modes of all eigensets were very similar, as shown in Figure 4; modes 3 through 8 also showed significant similarity and follow a similar pattern to the first two modes, but beyond that mode-mixing meant similarity was low (Figure S2). This makes direct mode to mode comparisons of higher order modes impossible. A feature of ANM is that the lowest modes account for the vast majority of the predicted motions (Figure S3). For mode 1, except for the clathrin-bound structure (3GD1), the absolute dot products were mostly above 0.9, indicating that the modes are nearly parallel. The set of first modes naturally form 2 clusters; the arrestin-3 structures cluster with the apo and IP6-bound ones, in contrast to the simple RMSD measurement, which puts arrestin-3 in its own cluster. The second cluster contains the peptide-bound and GPCR-bound arrestin-2 structures. However, despite the existence of visually identifiable clusters, all of the mode 1’s are strikingly similar; the farthest outlier (3GD1) still produces a mode 1 with an average absolute dot product of 0.68 with the other structures. While far lower than the others, this value would be virtually impossible to get by chance with random vectors in this dimension (Figure S4), suggesting that clathrin binding alters the dynamics of the protein. Mode 2 (Figure 4b) tells a virtually identical story, although the similarity between the two clusters, between the peptide- and GPCR-bound arrestin-2s and the rest, is a little lower.

Figure 4:

A pairwise dot product of the first and second modes of motion as computed by ANM for all 26 structures analyzed. Structures are color coded both by their ligands (left and bottom of graph), or whether they are arrestin-2 (gray) or arrestin-3 (red) (right of graph).

4.3. Comparison of Activated to Apo Arrestins

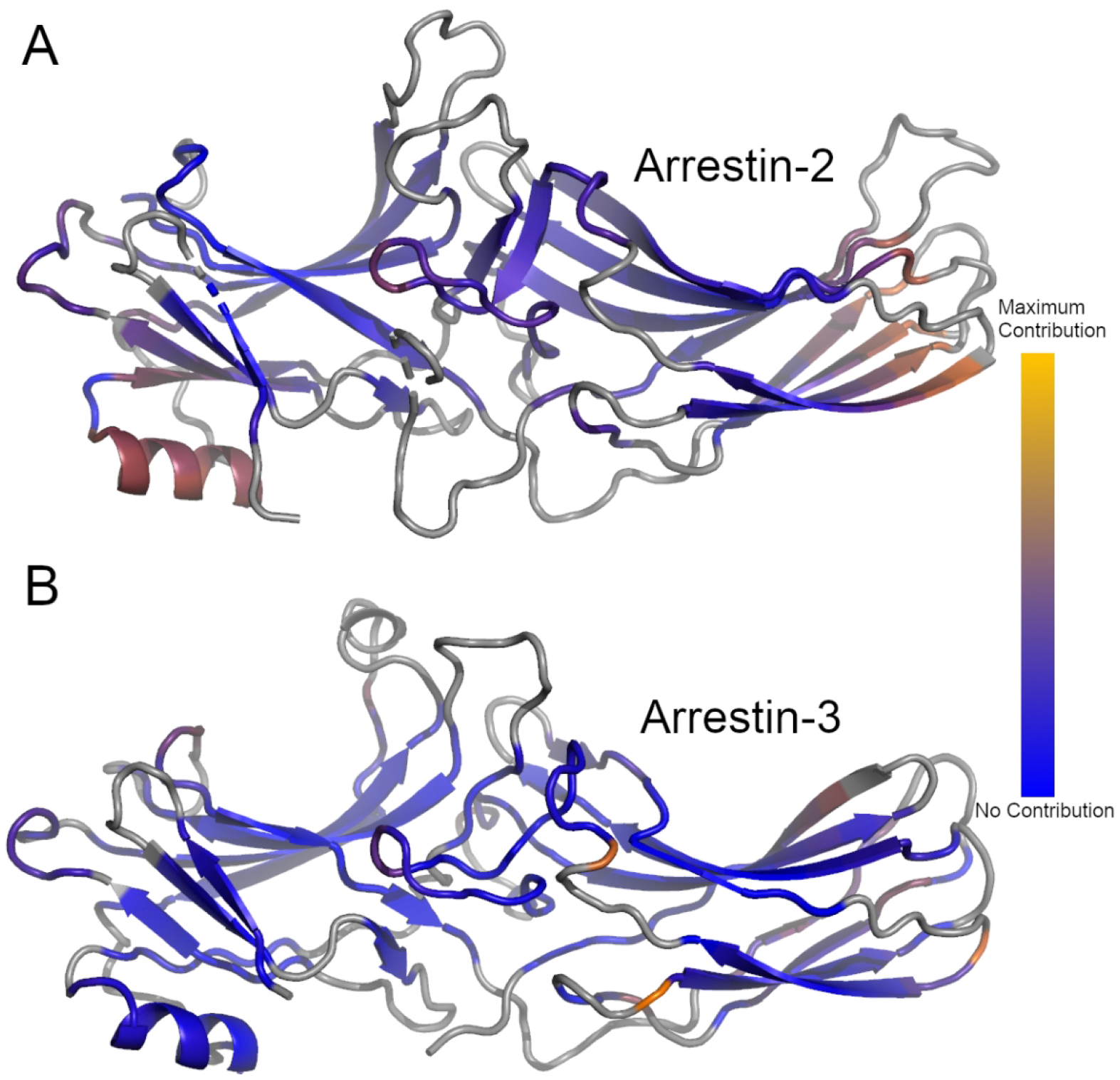

Although overall quite similar, the lowest modes for apo arrestins cluster separately from the activated arrestin-2 structures (Figure 4). This suggests that there are common changes to dynamics upon arrestin-2 activation by either a phosphopeptide or a GPCR but not IP6. We visualized this change in mode 1 by taking example structures from the GPCR-bound (6TKO) and apo (2WTR) arrestin-2 and mapping their respective mode 1s onto the structure of apo arrestin (Figure 5). This reveals that most of the difference in arrestin-2 comes from a change in the motion of α-helix 1, the middle of the lariat loop, and the C-domain β-sheets on the C-loop side (Figure 5a). The difference in arrestin-3 appear to be confined to the C-domain β-sheets and the center of the lariat loop (Figure 5b).

Figure 5:

Average difference in the per-residue dot product between the first mode of all unliganded and peptide-bound structures for Arrestin-2 (A) or Arrestin-3 (B). Gray regions represent structural elements not included in the ANM model. Blue regions represent regions which did not contribute to the differences in the dot product, orange regions represent regions of maximal contribution.

The change in dynamics between activated and apo arrestin can be quantified by computing the average amplitude of the difference between the respective first modes on a per-residue basis. Figure 5a shows the results by color-coding the structure of arrestin-2 using this quantity, which naturally highlights α-helix 1 and the C-domain β-sheets. Interestingly, this pattern is not retained when peptide-activated arrestin-3 is compared to the apo structures. Figure 5b shows that α-helix 1’s motions are similar in the two sets, and while there are differences in the C-domain β-sheet, they are smaller and involve fewer residues. We can further visualize these changes by looking at the difference in the vector of motion between two typical structures (2WTR/6TKO) and showing the change in their first mode of motion (Figure S5).

The other area where mode 1 differs between apo and activated arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 is the middle portion of the lariat loop, shown in the center of both structures. In the arrestin-3 structure shown, these residues are in contact with the bound peptide, making a dynamic change less surprising; the origin of the change in arrestin-2 is less clear.

4.4. Comparison of Apo to Clathrin-bound Arrestins

The lone clathrin-bound structure is nearly identical to apo arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 with an average RMSD of 0.66 Å from all apo arrestin structures. Despite this, it shows the most dramatic differences in its low mode dynamics compared to all other structures (Figure 4). This suggests that binding partners to arrestin can dramatically affect its dynamics without visibly perturbing its structure.

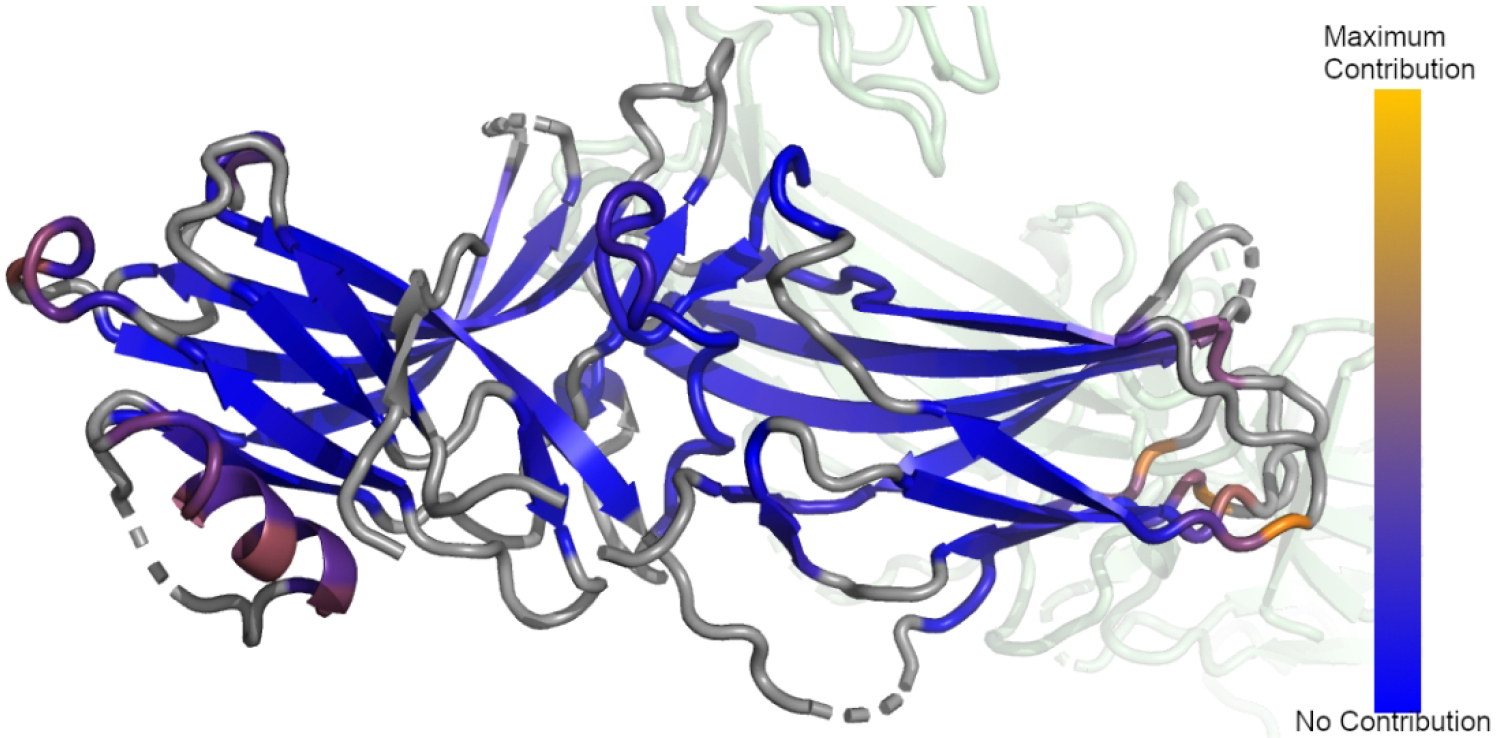

We mapped the average per-residue difference between the amplitudes of the first mode of all apo structures to clathrin bound arrestin-2 and we plotted these changes onto the structure of clathrin-bound arrestin-2 (3GD1) (Figure 6). As with comparing apo and activated arrestin-2 the differences in the motion are concentrated in α-helix 1 and the C-loop side of the C-domain β-sheets. The effects on the lariat loop are minimal, and there is an additional perturbation in motions in the semi-structures N-domain loop 44D-52R that does not appear in the differences between apo and active arrestin.

Figure 6:

Average difference in the per-residue dot product between the first mode of all unliganded and clathrin-bound Arrestin-2. Gray regions represent structural elements not included in the ANM model. Blue regions represent regions which did not contribute to the differences in the dot product, orange regions represent regions of maximal contribution.

We also examined the difference between the second mode of apo and clathrin bound arrestin-2 and found the differences were localized to the same regions (data not shown). Furthermore, inspection of the difference between active arrestin and clathrin bound arrestin revealed the same regions changing their motions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison to Experimental Studies

It is well known that arrestin’s structure and dynamics change upon activation [26, 57]. However, the precise nature of these changes, particularly in dynamics, and their relation to activity remains elusive despite numerous crystallographic studies [39–44, 46–51]. There also have been several HX-MS and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies that probe the solution structure and dynamics of arrestin and how those dynamics change upon activation [6, 22, 44, 57–62]. The aim of the present study is to use the existing crystallographic data to predict how structural changes upon activation change the resulting dynamics. Our work provides insights into two different stages of arrestin activation: (1) How arrestin dynamics change upon activation by a phosphopeptide or GPCR, and (2) how arrestin dynamics vary with subtle changes to the activating peptides phosphorylation status.

It is well established that the lowest modes produced by network models correlate well with HX-MS results [33, 35, 63]. There have been multiple HX-MS studies that probed the structural dynamics of apo wild-type arrestin, as well mutants that allow arrestin to assume an active-like conformation in the absence of a GPCR or activating peptide [6, 57, 59, 61], where these pre-activated mutants generally disrupt the charge balance within the polar core [64–66].

5.2. Low mode differences between active and apo arrestin

Our model predicts that arrestin-2’s motions change significantly upon activation by peptide or GPCR binding (Figure 5). We found that α-helix 1, the β-sheets bordering the C-edge loops, and L293 and 294K of the lariat loop of arrestin-2 show the greatest change in their dynamics as measured by the lowest mode of the ANM eigensets. These regions are of particular interest since they are three functionally important regions for arrestin. Vishnivetskiy et. al. showed that α-helix 1 plays a role in receptor binding, and that mutations to α-helix 1 disrupt receptor binding in arrestin-1 [22]. It is not surprising that this region shows up in our analysis as well, since this is precisely where the activating peptide of the GPCR binds. Meanwhile, the C-edge loops have been shown to bind to both clathrin and the cell membrane upon activation, and our observed change in dynamics may play a role in this [9, 10, 27]. Lysine 294 is in the middle of the lariat loop and binds phosphorylated residues on the GPCR; its homolog in arrestin-3 contacts bound IP6 [39, 41]. However, while it plays a role in receptor binding it does not serve as a phosphosensor [67]. As a result, we believe the calculations identify a set of allosterically linked sites on arrestin-2 that change their motions to enhance receptor binding and aid in endocytosis by simultaneously enabling membrane binding by coupling the motions of the GPCR activating peptide binding site with functional domains such as the C-loops which aid in membrane binding [27].

Activated arrestin-3 shows significantly less difference in its lowest mode dynamics compared to apo arrestin-3. Most of the residues identified appear to be isolated changes, although there are a cluster of dynamics changes in the β-sheets bordering the C-edge loops, and residues L295 and K296 of the lariat loop. However, α-helix 1 is conspicuously absent from this change. This suggests that arrestin-3 does not rely on α-helix 1 to enhance receptor binding, although its modest changes to dynamics upon activation may enhance membrane binding; it is worth noting that any interactions with the membrane are not included in the ANM model.

5.3. Low mode differences between clathrin-bound arrestin-2 and apo arrestin

Clathrin-bound arrestin-2 shows a similar fingerprint of differences when compared to both apo and active arrestin-2 with the exception of N-domain loop 44D-52R, which contains the NLS for vasopressin-bound arrestin-2 (P45-R51).[41] This region has been experimentally shown to change its structure based on the phosphorylation pattern of activating peptide bound to arrestin-2.[41] This fits well with the idea that clathrin binding to arrestin triggers internalization and suggests that this occurs at least in part by means of an allosteric interaction between the clathrin binding site and the NLS.[9]

5.4. Identification of sites affecting global dynamics

Our data reveals several disparate regions, which include α-helix 1, the β-sheets bordering the C-edge loops, the lariat loop, and the NLS, change both the amplitude and direction of their normal modes of motion in response to any sort of perturbation. This is particularly apparent in the clathrin-bound structure, which is extremely similar to the apo structures but has significantly different dynamics. These disparate sites change their motions in response to clathrin binding, even though this binding does not disrupt arrestin’s polar core and hence does not make it assume its active conformation (Figure 6). It is important to note that α-helix 1, the β-sheets bordering the C-edge loops, the lariat loop, and the NLS have essentially the same structure in the clathrin-bound and apo structures. Their response is almost entirely in their dynamics, revealing that these regions are coupled in terms of motions rather than structural changes. Going forward, it will be interesting to analyze mutations in these regions to identify specific residues that make key functional interactions.

5.5. Conclusion

We have performed a survey of all available structures of arrestin-2 and arrestrin-3 using ANM. We have shown that all apo structures of arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 have nearly identical dynamics, but their dynamics change dramatically upon activation. Arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 assume markedly different dynamics from each other upon activation, but these dynamics are nearly as dissimilar from each other as they are from apo arrestin. Examination of the lowest modes of motion in these models reveals that the differences are confined to a small set of functionally important regions in arrestin-2 but not arrestin-3. This change in dynamics upon activation could explain some of arrestin-2 activity binding active GPCRs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant U01DA051373. Emily Robinson was supported by NIH T32 GM 135134. We thank Dr. Michael Jenkins for material support and helpful conversations.

Footnotes

Statements and Declarations

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to declare

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in arrestin-anm at https://github.com/GrossfieldLab/arrestin-anm.

References

- 1.Gurevich VV and Gurevich EV, The structural basis of the arrestin binding to GPCRs. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2019. 484: p. 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Gastel J, et al. , beta-Arrestin Based Receptor Signaling Paradigms: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Complex Age-Related Disorders. Front Pharmacol, 2018. 9: p. 1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azzi M, et al. , Beta-arrestin-mediated activation of MAPK by inverse agonists reveals distinct active conformations for G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2003. 100(20): p. 11406–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eishingdrelo H, et al. , ERK and beta-arrestin interaction: a converging point of signaling pathways for multiple types of cell surface receptors. J Biomol Screen, 2015. 20(3): p. 341–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith ZG and Dhanasekaran DN, G protein regulation of MAPK networks. Oncogene, 2007. 26(22): p. 3122–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JY, et al. , Structural Mechanism of the Arrestin-3/JNK3 Interaction. Structure, 2019. 27(7): p. 1162–1170 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhan X, et al. , Arrestin-dependent activation of JNK family kinases. Handb Exp Pharmacol, 2014. 219: p. 259–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurevich VV and Gurevich EV, GPCR Signaling Regulation: The Role of GRKs and Arrestins. Front Pharmacol, 2019. 10: p. 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman OB Jr., et al. , Arrestin/clathrin interaction. Localization of the arrestin binding locus to the clathrin terminal domain. J Biol Chem, 1997. 272(23): p. 15017–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupnick JG, et al. , Arrestin/clathrin interaction. Localization of the clathrin binding domain of nonvisual arrestins to the carboxy terminus. J Biol Chem, 1997. 272(23): p. 15011–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laporte SA, et al. , beta-Arrestin/AP-2 interaction in G protein-coupled receptor internalization: identification of a beta-arrestin binging site in beta 2-adaptin. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(11): p. 9247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laporte SA, et al. , The interaction of beta-arrestin with the AP-2 adaptor is required for the clustering of beta 2-adrenergic receptor into clathrin-coated pits. J Biol Chem, 2000. 275(30): p. 23120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang DS, Tian X, and Benovic JL, Role of beta-arrestins and arrestin domain-containing proteins in G protein-coupled receptor trafficking. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2014. 27: p. 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaulieu JM and Caron MG, Beta-arrestin goes nuclear. Cell, 2005. 123(5): p. 755–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nobles KN, et al. , Distinct phosphorylation sites on the beta(2)-adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of beta-arrestin. Sci Signal, 2011. 4(185): p. ra51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao H, et al. , Identification of beta-arrestin2 as a G protein-coupled receptor-stimulated regulator of NF-kappaB pathways. Mol Cell, 2004. 14(3): p. 303–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang J, et al. , A nuclear function of beta-arrestin1 in GPCR signaling: regulation of histone acetylation and gene transcription. Cell, 2005. 123(5): p. 833–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shenoy SK, et al. , Regulation of receptor fate by ubiquitination of activated beta 2-adrenergic receptor and beta-arrestin. Science, 2001. 294(5545): p. 1307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang P, et al. , Beta-arrestin 2 functions as a G-protein-coupled receptor-activated regulator of oncoprotein Mdm2. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(8): p. 6363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witherow DS, et al. , beta-Arrestin inhibits NF-kappaB activity by means of its interaction with the NF-kappaB inhibitor IkappaBalpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(23): p. 8603–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurevich VV and Gurevich EV, The structural basis of arrestin-mediated regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther, 2006. 110(3): p. 465–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vishnivetskiy SA, et al. , The role of arrestin alpha-helix I in receptor binding. J Mol Biol, 2010. 395(1): p. 42–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seyedabadi M, et al. , Receptor-Arrestin Interactions: The GPCR Perspective. Biomolecules, 2021. 11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurevich VV and Benovic JL, Visual arrestin binding to rhodopsin. Diverse functional roles of positively charged residues within the phosphorylation-recognition region of arrestin. J Biol Chem, 1995. 270(11): p. 6010–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vishnivetskiy SA, et al. , An additional phosphate-binding element in arrestin molecule. Implications for the mechanism of arrestin activation. J Biol Chem, 2000. 275(52): p. 41049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheerer P and Sommer ME, Structural mechanism of arrestin activation. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2017. 45: p. 160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lally CC, et al. , C-edge loops of arrestin function as a membrane anchor. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 14258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eyal E, Yang LW, and Bahar I, Anisotropic network model: systematic evaluation and a new web interface. Bioinformatics, 2006. 22(21): p. 2619–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romo TD and Grossfield A, LOOS: an extensible platform for the structural analysis of simulations. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2009. 2009: p. 2332–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romo TD and Grossfield A, Validating and improving elastic network models with molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins, 2011. 79(1): p. 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seckler JM, et al. , The interplay of structure and dynamics: insights from a survey of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase crystal structures. Proteins, 2013. 81(10): p. 1792–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun E, et al. , Best Practices for Foundations in Molecular Simulations [Article v1.0]. Living J Comput Mol Sci, 2019. 1(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bahar I, et al. , Correlation between native-state hydrogen exchange and cooperative residue fluctuations from a simple model. Biochemistry, 1998. 37(4): p. 1067–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leioatts N, Romo TD, and Grossfield A, Elastic Network Models are Robust to Variations in Formalism. J Chem Theory Comput, 2012. 8(7): p. 2424–2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su JG, et al. , The Intrinsic Dynamics and Unfolding Process of an Antibody Fab Fragment Revealed by Elastic Network Model. Int J Mol Sci, 2015. 16(12): p. 29720–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein FC, et al. , The Protein Data Bank: a computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures. J Mol Biol, 1977. 112(3): p. 535–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burley SK, et al. , RCSB Protein Data Bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(D1): p. D437–D451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodcock HL, et al. , Vibrational subsystem analysis: A method for probing free energies and correlations in the harmonic limit. J Chem Phys, 2008. 129(21): p. 214109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q, et al. , Structural basis of arrestin-3 activation and signaling. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han M, et al. , Crystal structure of beta-arrestin at 1.9 A: possible mechanism of receptor binding and membrane Translocation. Structure, 2001. 9(9): p. 869–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He QT, et al. , Structural studies of phosphorylation-dependent interactions between the V2R receptor and arrestin-2. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang W, et al. , Structure of the neurotensin receptor 1 in complex with beta-arrestin 1. Nature, 2020. 579(7798): p. 303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang DS, et al. , Structure of an arrestin2-clathrin complex reveals a novel clathrin binding domain that modulates receptor trafficking. J Biol Chem, 2009. 284(43): p. 29860–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang H, et al. , Conformational Dynamics and Functional Implications of Phosphorylated beta-Arrestins. Structure, 2020. 28(3): p. 314–323 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Y, et al. , Molecular basis of beta-arrestin coupling to formoterol-bound beta1-adrenoceptor. Nature, 2020. 583(7818): p. 862–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milano SK, et al. , Nonvisual arrestin oligomerization and cellular localization are regulated by inositol hexakisphosphate binding. J Biol Chem, 2006. 281(14): p. 9812–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milano SK, et al. , Scaffolding functions of arrestin-2 revealed by crystal structure and mutagenesis. Biochemistry, 2002. 41(10): p. 3321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staus DP, et al. , Structure of the M2 muscarinic receptor-beta-arrestin complex in a lipid nanodisc. Nature, 2020. 579(7798): p. 297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yin W, et al. , A complex structure of arrestin-2 bound to a G protein-coupled receptor. Cell Res, 2019. 29(12): p. 971–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhan X, et al. , Crystal structure of arrestin-3 reveals the basis of the difference in receptor binding between two non-visual subtypes. J Mol Biol, 2011. 406(3): p. 467–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou HG, Standfuss J, Watson KA, Krasel C, Full length Arrestin2. 2009: Protein Databank. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eyal E, et al. , Anisotropic fluctuations of amino acids in protein structures: insights from X-ray crystallography and elastic network models. Bioinformatics, 2007. 23(13): p. i175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romo TD, Leioatts N, and Grossfield A, Lightweight object oriented structure analysis: tools for building tools to analyze molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem, 2014. 35(32): p. 2305–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hess B, Convergence of sampling in protein simulations. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys, 2002. 65(3 Pt 1): p. 031910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shukla AK, et al. , Structure of active beta-arrestin-1 bound to a G-protein-coupled receptor phosphopeptide. Nature, 2013. 497(7447): p. 137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen AH, et al. , Structure of an endosomal signaling GPCR-G protein-beta-arrestin megacomplex. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2019. 26(12): p. 1123–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carter JM, et al. , Conformational differences between arrestin2 and pre-activated mutants as revealed by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol, 2005. 351(4): p. 865–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanson SM, et al. , Differential interaction of spin-labeled arrestin with inactive and active phosphorhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006. 103(13): p. 4900–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim DK, et al. , Different conformational dynamics of various active states of beta-arrestin1 analyzed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J Struct Biol, 2015. 190(2): p. 250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim M, et al. , Conformation of receptor-bound visual arrestin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(45): p. 18407–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yun Y, et al. , Different conformational dynamics of beta-arrestin1 and beta-arrestin2 analyzed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2015. 457(1): p. 50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhuo Y, et al. , Identification of receptor binding-induced conformational changes in non-visual arrestins. J Biol Chem, 2014. 289(30): p. 20991–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bahar I and Rader AJ, Coarse-grained normal mode analysis in structural biology. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2005. 15(5): p. 586–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Granzin J, et al. , Crystal structure of p44, a constitutively active splice variant of visual arrestin. J Mol Biol, 2012. 416(5): p. 611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gray-Keller MP, et al. , Arrestin with a single amino acid substitution quenches light-activated rhodopsin in a phosphorylation-independent fashion. Biochemistry, 1997. 36(23): p. 7058–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gurevich VV and Gurevich EV, Structural determinants of arrestin functions. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 2013. 118: p. 57–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vishnivetskiy SA, et al. , Lysine in the lariat loop of arrestins does not serve as phosphate sensor. J Neurochem, 2021. 156(4): p. 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in arrestin-anm at https://github.com/GrossfieldLab/arrestin-anm.