Abstract

Titanium is the metal of choice for dental implants because of its biocompatibility and ability to merge with human bone tissue. Despite the great success rate of dental implants, early and late complications occur. Coating titanium dental implant surfaces with polyethyleneimine/plasmid DNA (pDNA) polyplexes improve osseointegration by generating therapeutic protein expression at the implantation site. Lyophilization is an approach for stabilizing polyplexes and extending their shelf life; however, most lyoprotectants are sugars that can aid bacterial growth in the peri-implant environment. In our research, we coated titanium surfaces with polyplex solutions containing varying amounts of lyoprotectants. We used two common lyoprotectants (sucrose and polyvinylpyrrolidone K30) and showed for the first time that sucralose (a sucrose derivative used as an artificial sweetener) might act as a lyoprotectant for polyplex solutions. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were used to quantify the transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity of the polyplex/lyoprotectant formulations coating titanium surfaces. Polyplexes that were lyophilized in the presence of a lyoprotectant displayed both preserved particle size and high transfection efficiencies. Polyplexes lyophilized in 2% sucralose have maintained transfection efficacy for three years. These findings suggest that modifying dental implants with lyophilized polyplexes might improve their success rate in the clinic.

Keywords: Polyplexes, gene delivery, non-viral gene delivery, lyophilization, lyoprotectants, stability, titanium dental implants, osseointegration

Introduction

Titanium is a biocompatible metal that allows viable human tissues to integrate with its surface via the osseointegration process1. Over the last two decades, advancements in the surface microarchitecture and overall design of dental implants have increased their success rate2. Furthermore, as compared to previous protocols, the recently used protocols for loading implants with prosthetic components, namely the early and immediate loading protocols, require much less time3, thereby increasing the dental implant success rate3. Although dental implants have a success rate of at least 90%, early and late complications with dental implants still occur, with osseointegration failure being a significant cause of early implant failure2. There is also an unmet need to improve osseointegration by developing mechano-inductive and biologically active implant surfaces4–7. Creating such surfaces may induce an osteogenic response at the implant-bone interface, promoting osseointegration. This is particularly important to people with systemic conditions or behaviors that interfere with the process, such as uncontrolled diabetes, osteoporosis, or smoking2, 8.

A range of techniques classed as morphological, physical, and biological changes have been examined to improve the performance of titanium dental implants. Morphological changes can be made using techniques such as sandblasting9, anodic-oxidation10, and laser ablation11. Physical modifications, in contrast, are based on changing the surface wettability or surface charge12, 13. Surfaces of dental implants can also be biologically modified by coating them with regenerative factors such as recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rh-BMP-2) or (rh-BMP-7). Previous research has shown that protein delivery approaches can increase local bone growth at the peri-implant site4, 5. While proteins can be a strong therapeutic tool to change titanium surfaces, this method has some significant drawbacks, such as protein denaturation due to 3D structure distortion, protein conjugation, or triggering immunological reactions14. Proteins are also difficult to include in sustained-release formulations because of their temperature and pH sensitivity and their proclivity for denaturation15. Because of these characteristics, developing single-dose protein therapies with long-term therapeutic effects is difficult.

Gene delivery may circumvent these challenges by enabling the production of therapeutic proteins by a patient’s cells. With such an approach, a person’s cells could be induced to create their own medicine, deliver it locally, and stop after a defined time. Gene delivery has already shown great success in vaccines, namely the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines16, 17. However, the stability of the delivery system used in the mRNA based COVID vaccines has become a significant concern18, 19, especially since it is difficult to maintain the cold temperature conditions required by the lipid nanoparticle delivery system. While the lipid nanoparticles used in mRNA-based COVID vaccines are effective gene-delivery vehicles, older gene-delivery vehicles like polyplexes fabricated from polyethyleneimine (PEI) and nucleic acids can be mixed with lyoprotectants and lyophilized without significant loss of transfection activity20–23. In addition, these lyophilized formulations have previously been shown to retain transfection activity for up to 6 months24.

The most commonly used lyoprotectants are sugar derivatives such as sucrose, trehalose, and maltitol, which can preserve the physical properties of lyophilized particulate formulations, such as liposomes25, proteins26, and nonviral gene delivery vectors27. Several hypotheses have been proposed in the literature to explain how sugars preserve the physical characteristics of lyophilized particulate formulations during the lyophilization process. Crowe et al. suggest that sugars interact with charged or polar regions on the surface of suspended particles in a manner similar to how the particles would interact with water, which allows them to remain stable as water is removed during lyophilization25, 28. Another explanation, the “vitrification hypothesis”, notes that rapidly frozen sugar solutions produce a glassy matrix (i.e. a non-crystalline, amorphous solid) during freezing, and proposes that immobilization in this glassy matrix is sufficient to prevent particle aggregation and thus preserve the particles within26–29. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that sugars can be utilized to maintain particle size during freezing, implying that sugars can minimize interactions between particles27. S.D. Allison et al. also reported that sugars keep particles separate within the unfrozen fraction, preventing aggregation during freezing30. In addition, sugars have relatively low surface tension, allowing phase-separated particles to remain dispersed within the unfrozen excipient solution, therefore maintaining their particle size28, 30.

Previously, our lab investigated the loading of lyophilized gene-delivery vehicles onto titanium dental implant surfaces using sucrose as the lyoprotectant6. Because sucrose is cariogenic and dental implants are already at a higher risk of bacterial growth, we suggested that sucrose be replaced with a lyoprotectant that bacteria cannot metabolize. Based on that recommendation, we chose to investigate the non-metabolizable sucrose derivative “sucralose,” a vital component of the artificial sweetener “Splenda,” as a lyoprotectant for PEI-pDNA polyplexes in this study. Sucralose, a chemical with a unique set of physical properties, was also recently identified as a potential potent lyoprotectant in a recent paper by Meng-Lund et al. and confirmed as a protein lyoprotectant in a follow-up study31, 32. We compared sucralose to other lyoprotectants in gene-delivery coatings of titanium dental implant surfaces and demonstrated sucralose’s ability to preserve transfection activity over time.

Experimental

Preparing titanium discs

Titanium discs (12.00 ± 0.04 mm in diameter and 2.99 ± 0.02 mm in thickness) made of commercially pure titanium were prepared as described previously6, 7. Briefly, a grinder–polisher (Ecomet 3, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) was used to polish the discs with an ascending series of grinding papers (CarbiMet, Buehler) with grit numbers of 120, 240, 400, and 600. Then, the titanium discs were sandblasted (EWL Type 5423, KaVo) using a 50-μm white aluminum oxide blasting compound (Ivoclar Vivadent, Liechtenstein). Then, the sandblasted discs were sonicated (Branson 5200, Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) twice in ultrapure water for 5 min to eliminate residues of the aluminum oxide blasting compound. The discs were then soaked in acetone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 15 min to remove any contaminants from their surface. Then they were acid etched with 30% nitric acid (ThermoFisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) for 30 min. Finally, the discs were rinsed with ultrapure water and stored in 70% ethanol at room temperature.

Plasmid purification

pDNA encoding EGFP was purified from DH5α Escherichia coli (Plasmid 13031, Addgene, UK) that had been previously transformed. First, the bacteria were cultured under antibiotic selection, and subsequently, the plasmid was purified using the GenElute HP Endotoxin-Free Plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Plasmid yield and quality were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), measuring absorbances at 260nm and 280nm.

Polyplex fabrication with different lyoprotectant types and concentrations

Polyplex solutions were prepared as previously described33. Briefly, a 0.26 μg/μL polyethyleneimine (PEI) (branched, average Mw ~25 kDa) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) solution and 0.2 mg/mL pEGFP solution were prepared in equal volumes of DNAse/RNAse-free water (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The PEI solution was added to the pEGFP solution, vortexed for 30 seconds, then incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes to allow the pEGFP and PEI to complex. The resulting polyplexes have nitrogen (N) to phosphate (P) ratio (N/P ratio) equal to 10, which was demonstrated to have maximum transfection efficiency with minimal cytotoxicity in previous work33, 34. Sucrose (ThermoFisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ), sucralose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and polyvinylpyrrolidone K30 (PVP, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used as lyoprotectants by preparing stock solutions of 40% (w/v) sucrose, 20% (w/v) sucralose, and 20% (w/v) PVP in DNAse/RNAse-free water. The differences in-stock solution concentrations are due to the different solubilities of the lyoprotectants in water35–37. After preparing the polyplex solutions, stock lyoprotectant solution was added to bring the lyoprotectant concentration to the desired level in the final polyplex solution, and the combined solution was thoroughly mixed. Sucrose concentrations in the final polyplex solutions were 0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, 5% and 10%, while sucralose and PVP concentrations were 0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, 5% and 7.5%.

Physical Characterization of polyplex formulations

Microfuge tubes containing the polyplex formulations were transferred into a −80°C freezer (U 725 Innova, New Brunswick) until frozen and then lyophilized (FreeZone 4.5 −105, Labconco), at −105 °C and with a vacuum pressure of 0.021 mBar. Formulations were reconstituted using ultrapure water, then a volume of 1 mL was transferred into a polystyrene cuvette, and another 1 mL was transferred into a polystyrene folded capillary cell. The hydrodynamic size, polydispersity index (PDI), and surface charge were measured using dynamic light scattering and electrophoretic light scattering with a Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern, UK).

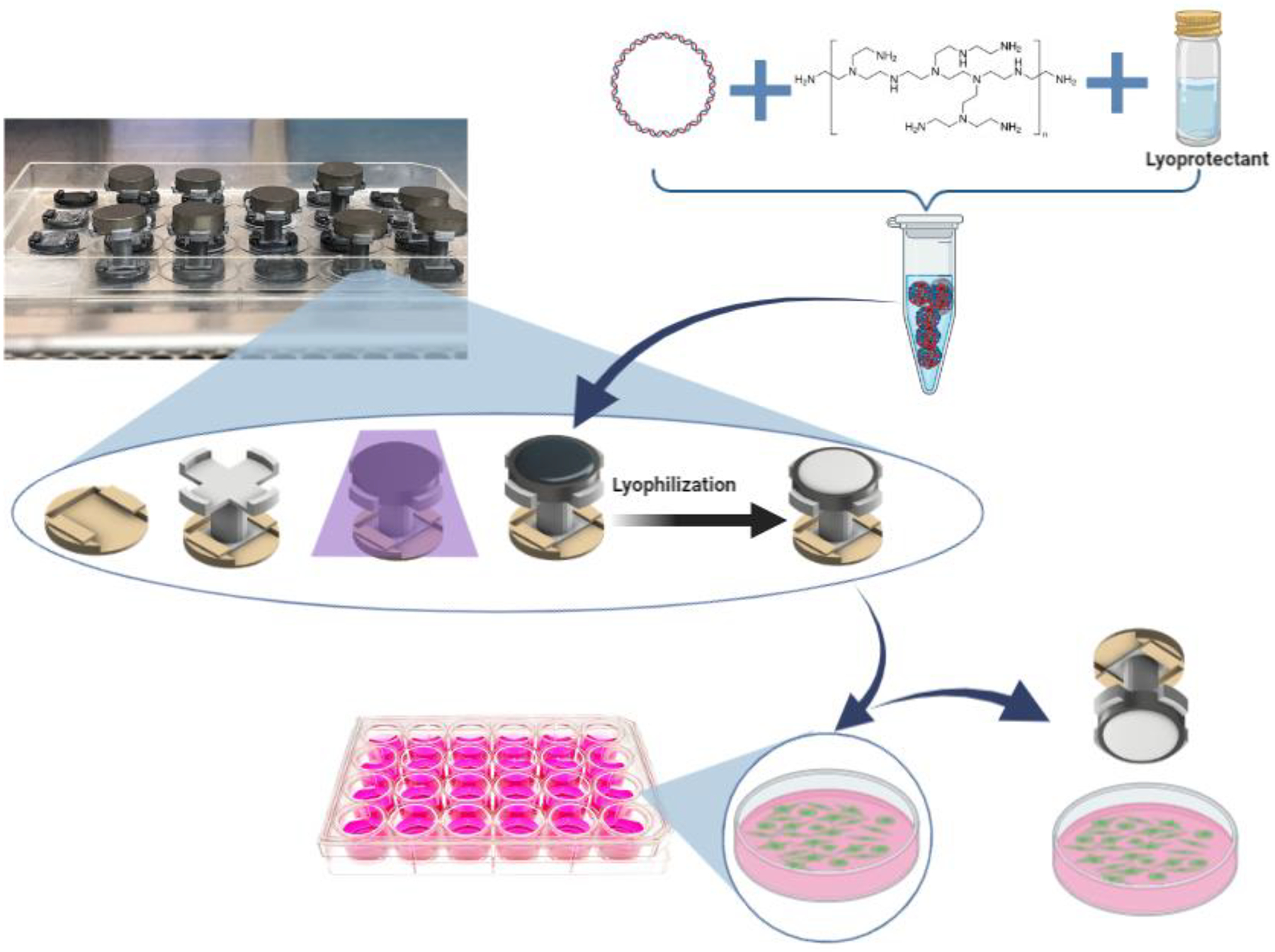

Coating titanium discs with prepared polyplex formulations

Titanium discs were sonicated twice with ultrapure water for 15 min, then rinsed with 70% ethanol. Next, the discs were attached to 3D printed “holders”; the holders were fitted to a modified lid of a 24-well culture microplate (Figure 1). The lid with attached holders and discs was then transferred to a biosafety cabinet and sterilized by exposure to UV light for 30 mins. Then the titanium surfaces were covered with a volume of polyplex solution containing 5 μg of pEGFP, then coated titanium discs were covered with an inverted 24-well culture microplate (DOT Scientific, Burton, MI). The plate was frozen at −80° C and was then lyophilized (FreeZone 4.5 −105, Labconco).

Figure 1:

Schematic showing the preparation of titanium discs and their use in transfection. First, a base is affixed to the lid of a 24 well cell culture microplate, followed by a disc holder and then a titanium disc is attached to the disc holder and then sterilized by UV radiation. Next, the polyplex suspension is created by mixing polyplexes (made from pDNA + PEI), with the desired lyoprotectant and then using it to cover the titanium disc surface. The polyplexes were then lyophilized on the titanium disc surface before being utilized to transfect HEK 293T cells by immersing the discs in DMEM medium (with cells) for 4 hours. See methods for more details.

Quantification of polyplex (pDNA) release from the titanium surface

Titanium discs were placed into 24-well cell-culture plates and sterilized with UV irradiation. Polyplex formulations were prepared as described previously, and a volume containing 5 μg of pDNA was used to coat the surface of the titanium discs. The microplate was frozen at −80°C and then lyophilized. After lyophilization, 750 μL of DNAse/RNAse-free water was added to each well, and the titanium discs were submerged into the water and incubated for 4 hr at 37°C. Aliquots of 100 μL were withdrawn at predetermined time intervals and replaced with an equal volume of DNAse/RNAse- free water. The withdrawn aliquot was transferred into a 96-well plate and mixed with 100 μL of 3.57 mg/mL heparin sodium salt solution (heparin from porcine of intestinal mucosa, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), to release the pDNA from the polyplex, which was necessary to enable subsequent pDNA detection/quantification38. The samples were stored at 4°C until the end of the study. A Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to quantify pDNA content in each sample.

Culture of human embryonic kidney 293T Cells

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK 293T) cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured as a monolayer in media containing: Gibco Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) media (Life Technologies Limited, Paisley), 1% v/v HEPES, 1% v/v sodium pyruvate, 1% v/v Glutamax (all from Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, NY), 10% v/v fetal bovine serum FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA), and 0.1% v/v gentamycin (IBI Scientific, Dubuque, IA). Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 (Sanyo Scientific, Wood Dale, IL). Cells were passaged using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies Corporation, Austin, TX), and the passage number of cells was between 5 and 20.

Transfecting cells with polyplex-coated titanium discs

HEK 293T cells were seeded into the wells of 24-well tissue microculture plates at a seeding density of 27,000 cells/cm2. After 24 hr of culture, the DMEM media was replaced with FBS-free media following previously reported protocols34, 39. The 24-well plate lid, holding the modified titanium discs coated with the lyophilized polyplexes (containing pEGFP), was used to replace the original lid of the seeded culture plate. The media was in contact with the modified titanium discs, and the plate was incubated for 4 hr in a humidified incubator. After the incubation time, the discs were removed, and the FBS-free media was replaced with DMEM media (i.e., containing 10% FBS). After 48 hr of incubation, cells were trypsinized with 200 μL of 0.25% trypsin, and then the trypsin was quenched using complete media. Cell suspensions were collected in round-bottomed polystyrene tubes (BD Biosciences Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA), and were acquired using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and then analyzed with FlowJo software. Untreated cells were used to establish a fluorescence threshold above which the cells were transfected. Transfection efficiencies were expressed as a percent of cells present in the live cell gate (determined by forward scatter versus side scatter analysis) that were transfected.

Cell viability

Cell viability was determined using the MTS cell proliferation assay, CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI), and was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were treated with polyplex-coated titanium discs (described above) for 4 hr. Forty-eight hrs after treating the cells, 100 μL of MTS assay reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) was added to the cells seeded in the 24-well tissue microculture plate. Cells were then incubated for 4 hrs in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Then 100 μL of the media from each well was transferred into a 96-well tissue microculture plate. A SpectraMax Plus384 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was used to assess the viability of the cells based on the relative level of the soluble formazan formed at λmax 490 nm. Untreated HEK 293T cells were used as a control group, and the results were expressed as percent viability relative to the control group.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad PRISM (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used to conduct the statistical tests. Treatments and controls were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Values are expressed as mean± standard deviation (SD), and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results:

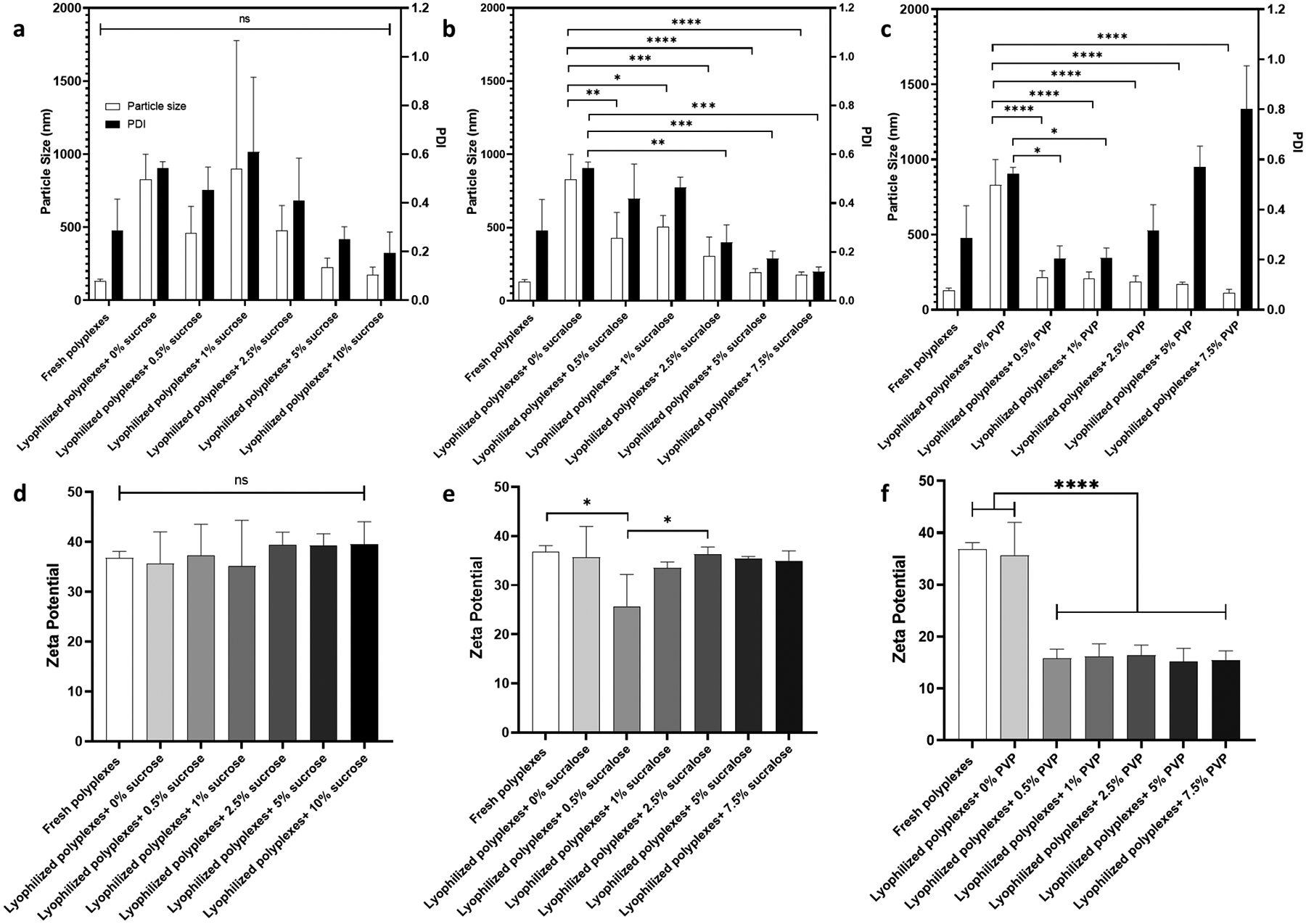

Particle size and surface charge of polyplexes

Polyplexes were formulated as described in the polyplexes fabrication part in the experimental section. After lyophilization of polyplexes with different types and concentrations of lyoprotectants, the particle size, PDI, and surface charge were measured and compared to freshly prepared polyplexes (Figure 2, a–c). The mean particle size of the freshly prepared polyplexes was 130.3± 15.01 nm, and the PDI was 0.287± 0.128. The mean particle size and PDI increased after lyophilization, likely due to the polyplexes aggregating due to the lyophilization process. Sucrose and sucralose prevented polyplex aggregation during lyophilization at concentrations above 2.5%. An increase in PVP concentration also led to a reduction in the particle size; however, an increase in PDI was associated with increases in PVP concentration (Figure 2, c). The surface charge of the freshly prepared polyplexes was 36.8 ± 1.3 mV. The surface charge of polyplexes lyophilized in the presence of sucrose and sucralose was not significantly different from freshly prepared polyplexes; the exception being when polyplexes were lyophilized with 0.5% sucralose. In contrast, polyplexes lyophilized in the presence of PVP showed a significant decrease to ~ 15 mV (Figure 2, d–f).

Figure 2:

Particle diameter size, PDI, and surface charge. Particle size and PDI for polyplexes lyophilized with different concentrations of sucrose, (a) sucralose, (b), and PVP (c). The corresponding surface charge measurements for sucrose (d), sucralose (e), and PVP (f). Values are expressed as mean+ SD, n = 3. Significant differences were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey`s multiple comparisons tests (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

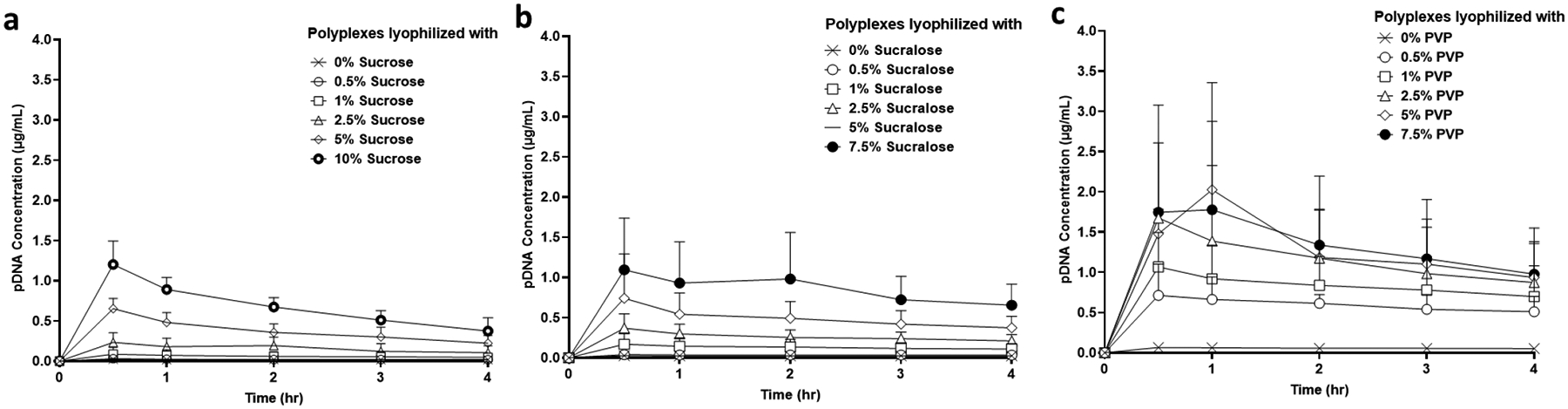

In vitro release studies

Titanium discs coated with indicated polyplex/lyoprotectant formulations were incubated in DNase/RNase-free water, and aliquots were removed at various time points over 4 hr. The PicoGreen assay was used to quantify the amount of pDNA within the withdrawn aliquots (Figure 3). Varying degrees of release of detectable pDNA were observed within 30 minutes from each of the samples, which is indicated by the release of pDNA either in soluble form or in the form of polyplexes. In addition, the rate of release of detectable pDNA increased with increasing lyoprotectant concentration. That polyplex release could be dependent on lyoprotectant concentration has been supported from a previous report40.

Figure 3:

pDNA release profile from polyplex-coated titanium discs. pDNA release profile from polyplexes lyophilized with different concentrations of sucrose (a), sucralose (b), and PVP (c). Values are expressed as mean± SD, n = 3.

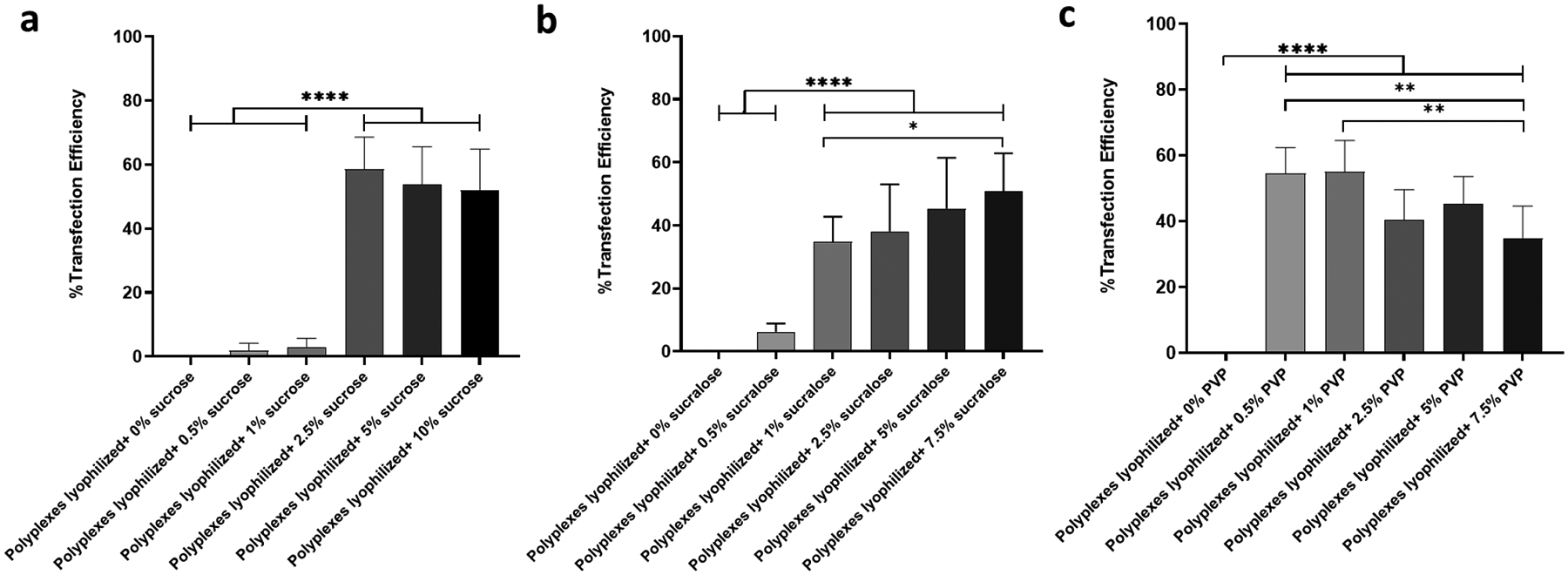

Transfecting cells with polyplex-coated titanium discs

Titanium discs were sandblasted, and then acid etched before coating them with polyplexes (containing pEGFP) to produce surfaces that mimic the commercially available dental implants41, 42. Forty-eight hr after culturing HEK 293T cells with variously coated titanium discs (for 4 hr), flow cytometry was used to quantify the percentage of transfected cells. It was found that the transfection efficiency of cells cultured with titanium discs coated with polyplexes lyophilized without lyoprotectant was as low as 0.98% (Figure 4). However, when polyplexes were lyophilized in the presence of 2.5%, 5%, and 10% sucrose, transfection efficiencies of 61.51%, 57.74%, and 59.94% were observed. In addition, polyplexes that were lyophilized in the presence of 1%, 2.5%, 5% and 7.5% sucralose had transfection efficiencies equal to 47.04%, 46.67%, 58.74% and 61.41%, respectively. The percentage transfection efficiency for cells treated with titanium discs coated with polyplexes lyophilized using 0.5% and 1% PVP was 58.89% and 60.34%, respectively. Interestingly PVP concentrations above 1% resulted in decreased transfection efficiencies. The fold-change in the median fluorescence intensity due to EGFP gene expression is shown in Figure 5. NPs lyophilized using 2.5% sucrose or higher, and 1% sucralose or higher displayed significant increases in fold-changes in median fluorescence intensity due to EGFP gene expression in HEK 293T cells compared to NPs lyophilized using 1% sucrose or less, and 0.5% sucralose or less. Additionally, HEK 293T cells transfected with NPs lyophilized using 0.5% PVP or higher, showed significant increases in the fold-change in the median fluorescence intensity due to EGFP gene expression than cells transfected with NPs lyophilized without lyoprotectant.

Figure 4:

Transfection efficiency of HEK 293T cells using titanium discs coated with polyplexes lyophilized with or without lyoprotectants. Transfection efficiency measured 48 hr after treating cells with polyplexes lyophilized with different concentrations of sucrose (a), sucralose (b), and PVP(c). Values are expressed as mean+ SD, n = 4–9. Significant differences were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 5:

Fold-change in median fluorescence intensity of HEK 293T cells transfected with pEGFP using titanium discs coated with polyplexes lyophilized with or without lyoprotectants. Fold-changes in median fluorescence were evaluated 48 hr after treating cells with polyplexes lyophilized with different concentrations of sucrose (a), sucralose (b), and PVP (c). Values are expressed as mean+ SD, n = 3–9. Significant differences were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (****p < 0.0001).

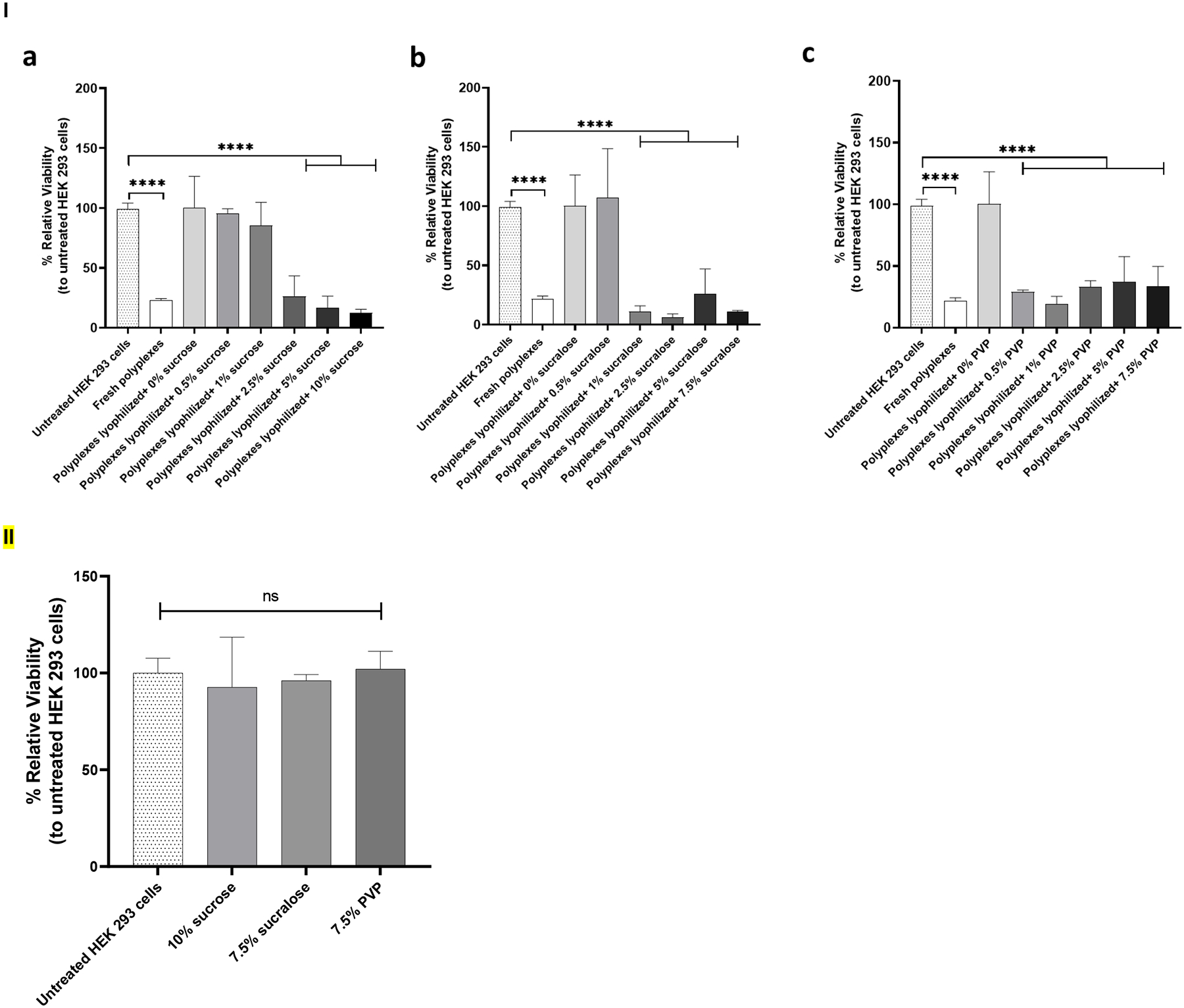

Viability of cells after treatment

Cell viability was quantified using an MTS assay 48 hr after a 4 hr incubation with the indicated titanium discs. Results revealed that an increase in the concentration of lyoprotectants led to a reduction in cell viability (Figure 6, I). Viability decreased significantly to 22.98% when cells were treated with freshly prepared polyplexes. The viability of transfected cells with polyplexes lyophilized using 0.5% and 1% sucrose was 95.33% and 85.14%, respectively. While the viability of cells transfected with polyplexes that were lyophilized using 2.5%, 5%, and 10% sucrose showed a significant decrease to 26.22%, 16.45%, and 12.41%, respectively. Polyplexes that were lyophilized using 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, 5% and 7.5% sucralose showed viabilities of 107%, 10.98%, 6.20%, 25.83% and 10.93%, respectively. The viabilities of cells that were lyophilized using 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, 5% and 7.5% PVP were 28.99%, 19.19%, 32.98%, 37.22% and 33.34%, respectively.

Figure 6:

I) Cell viability of HEK 293T cells treated with titanium discs coated with polyplexes lyophilized with or without lyoprotectants. Cell viability was measured 48 hr after treating cells with indicated polyplex-coated titanium discs in the presence or absence of sucrose (a), sucralose (b), and PVP (c) as a lyoprotectant. Values are expressed as mean + SD, n = 2–7. Significant differences were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). II) Cell viability was measured 48 hr after treating with lyoprotectant solutions alone. Values are expressed as mean + SD, n = 3. Significant differences were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests.

Viability of cells after treatment with lyoprotectants only

To check the toxicity of the used lyoprotectants; cell viability was quantified using an MTS assay 48 hr after a 4 hr incubation with different solutions containing lyoprotectants without the polyplex, (Figure 6, II). The concentration of lyoprotectants in the solutions used to treat cells were 10% sucrose, 7.5% sucralose, and 7.5% PVP. The viability of the cells was found to be comparable to the viability of the untreated cells. The viability of the cells that have been treated with solutions that contain 10% sucrose, 7.5% sucralose, and 7.5% PVP were 92.67%, 96.11%, and 102.00%, respectively.

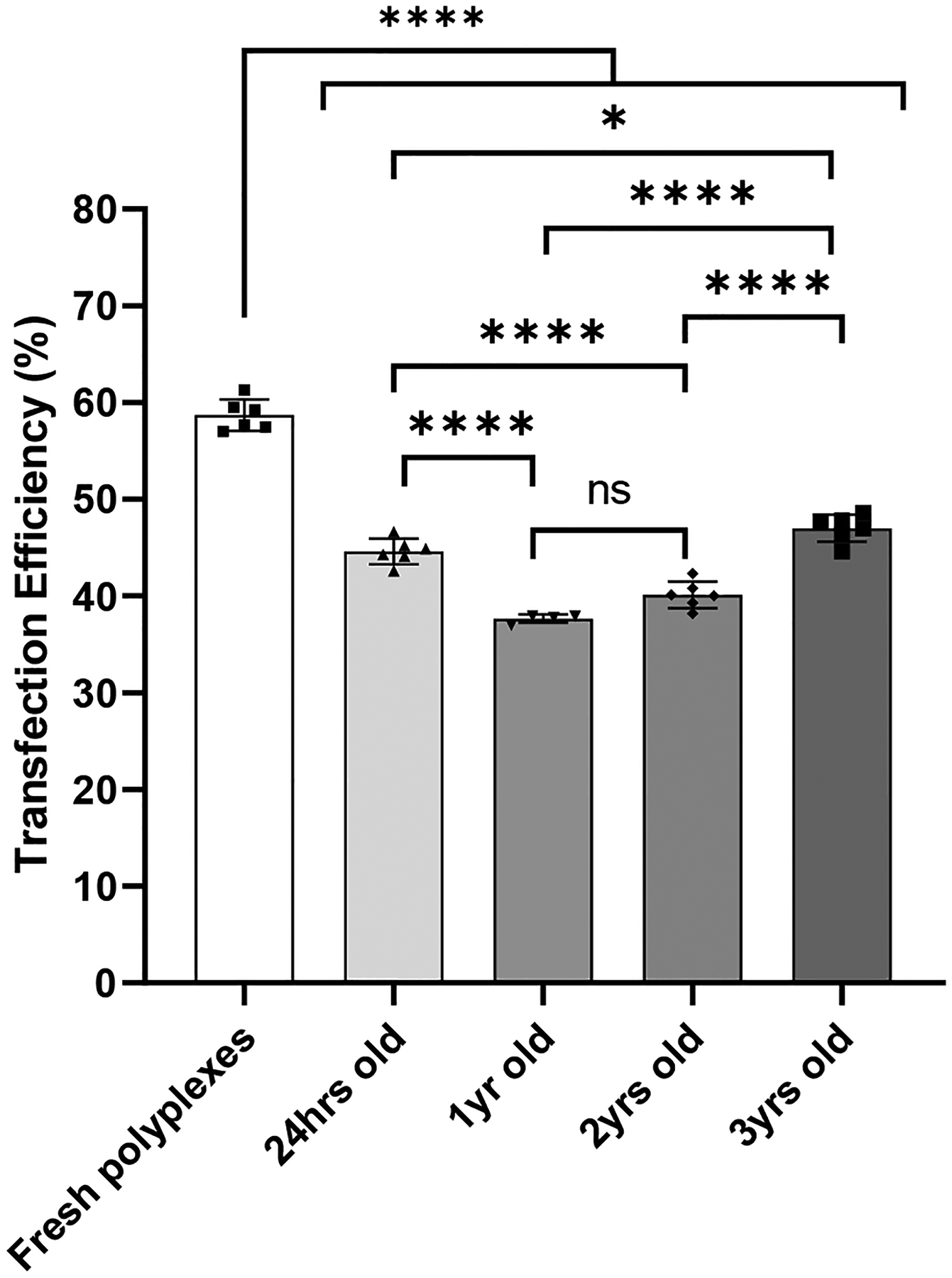

Transfection efficiency after long-term storage

Polyplex solutions containing 2% sucralose were lyophilized, stored, then used to transfect HEK 293T cells periodically over 3 years (Figure 7). Transfection efficiency was analyzed with flow cytometry. The transfection efficiency of polyplex solutions lyophilized with 2% sucralose declined from 58% to 44% after lyophilization, then stayed above 35% for 3 years.

Figure 7:

Transfection efficiency of HEK 293T cells was measured 48 hr after transfection with polyplexes that were freshly prepared or lyophilized in 2% sucralose and stored for 24 hr, 1 year (yr), 2 yr, or 3 yr. Values are expressed as mean +SD, n = 4–6. Significant differences were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001).

Discussion

Our prior work demonstrated that lyophilizing gene delivery formulations onto titanium dental implant surfaces were a potential method for gene delivery to the peri-implant environment6. In our prior study, we used sucrose as a lyoprotectant, which can stimulate bacterial growth. Various sugars, including sucrose, have been widely used as lyoprotectants for various lyophilizing products, including gene delivery systems43. However, using any sugar as an excipient in the oral environment carries a significant risk for dental implant failure. Moreover, Titanium dental implants are hydrophilic, microtextured, and have high surface energy to improve their integration with the jawbones44. Unfortunately, these similar characteristics facilitates the biofilm formation by exposing of titanium surface to saliva45. In addition, the bacterial cells in these biofilms produce acids upon exposure to fermentable carbohydrates, like sugars46. As a result of the bacterial metabolism, the medium pH drops, which might encourage biomaterial corrosion and deterioration47. Sucralose, a commonly used artificial sweetener, cannot be metabolized by bacteria, and therefore it does not support bacterial growth48. In addition, H. Meng-Lund et al. showed that sucralose might be an interesting lyoprotectant excipient due to its physical properties31, then demonstrated that it can function as a lyoprotectant for protein solutions32.

No prior investigation of sucralose as a lyoprotectant for gene delivery vectors has been published, despite its apparent potential in such an application. In the current work, we investigated using sucralose as a lyoprotectant for gene delivery vehicles and compared its performance to the commonly used lyoprotectants sucrose and PVP. We hypothesized that sucralose, a sucrose derivative, is a possible alternative lyoprotectant for lyophilizing polyplexes intended for oral applications as it is a non-toxic and non-cariogenic substance48–50. We found that all 3 lyoprotectants could preserve transfection activity after lyophilization, though PVP introduced higher particle size variability and reduced particle surface charge. However, all three lyoprotectants caused a significant loss of cell viability when transfection occurred. The loss of cell viability may result from the documented cytotoxicity caused by PEI-pDNA polyplexes. By comparing the transfection efficiency and viability data, we can see that the loss of viability only occurs when there is significant transfection, which implies that the observed loss of viability is caused by transfection. Since the viability is low after transfection, it is clear that future work should involve optimizing the dose of polyplexes to minimize cell death while maximizing the expression of the protein encoded by the pDNA. Our release studies showed that higher concentrations of lyoprotectant resulted in a higher total release of detectable pDNA from the dental implant surfaces. The higher release rates correlated with transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity as would be expected due to the presence of PEI which is known to simultaneously affect both these parameters23. The release profiles all show an immediate release of polyplexes matching the release studies from our earlier work6, 7.

Prior to beginning experiments comparing sucralose to other common lyoprotectants, we had found that sucralose was able to preserve the transfection activity of polyplexes when included at a concentration of 2% (Figure 7). Therefore, we experimented to determine how long the sucralose could preserve transfection activity and stored vials of polyplexes lyophilized in 2% sucralose at room temperature. It was apparent that storage conditions were minimally detrimental to transfection efficiencies of lyophilized polyplexes (comparing 24 hour-old vs 1-, 2-, and 3-year-old lyophilized polyplexes) and that instead the lyophilization process itself primarily contributed to the drop in transfection efficiency when compared to freshly prepared complexes. These findings demonstrate that sucralose can preserve polyplexes long-term without considerable activity loss during storage.

Our findings reveal that sucralose can act as a lyoprotectant for polyplex-based gene delivery vectors and keep them fresh for a long time. Sucralose is a strong candidate for use in lyophilized gene delivery formulations intended for the oral environment due to its inability to be metabolized by bacteria. Future work should assess the efficacy of the gene-delivery coating described here in an in vivo peri-implant model and compare the bacterial growth from sucrose-based coatings against those from sucralose-based coatings. The preservation of transfection activity for multiple years after lyophilization could also make transportation and distribution of gene delivery therapeutics easier. The current COVID-19 vaccines based on mRNA use lipid nanoparticles as the delivery vehicle and these particles must be kept cold during transportation. Formulating gene-delivery therapeutics as lyophilized products that are functional after 3 years of storage at room temperature could circumvent the need for chilled transportation, making delivery and widespread use of these therapeutics more feasible and less costly.

Conclusion

In this study, we showed that sucralose matches the performance of sucrose and PVP when used as a lyoprotectant to preserve gene delivery vehicles on dental implant surfaces. The level of transfection after lyophilization was similar between sucrose, sucralose, and PVP across a range of working concentrations. In addition, sucralose matched sucrose in its ability to perform as a lyoprotectant without the changes in surface charge and particle size variability seen with PVP. Also, the complexes lyophilized in the presence of 2% sucralose are amenable to long-term storage (at least 3 years at room temperature). This work demonstrates that sucralose can be used as a lyoprotectant for PEI-pDNA polyplexes in settings sensitive to sugars, such as the peri-implant environment.

Acknowledgments

A.K.S acknowledges support from the Lyle and Sharon Bighley Chair of Pharmaceutical Sciences and the National Institutes of Health grants P30 CA086862 and R21 DE031042-01A1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Brånemark R; Brånemark P; Rydevik B; Myers R, Osseointegration in skeletal reconstruction and rehabilitation: A review. Journal of rehabilitation research and development 2001, 38, 175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alghamdi HS; Jansen JA, The development and future of dental implants. Dent Mater J 2020, 10.4012/dmj.2019-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallucci GO; Hamilton A; Zhou W; Buser D; Chen S, Implant placement and loading protocols in partially edentulous patients: A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res 2018, 29, 106–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leknes KN; Yang J; Qahash M; Polimeni G; Susin C; Wikesjö UME, Alveolar ridge augmentation using implants coated with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: radiographic observations. Clin Oral Implants Res 2008, 19 (10), 1027–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Susin C; Qahash M; Polimeni G; Lu PH; Prasad HS; Rohrer MD; Hall J; Wikesjö UME, Alveolar ridge augmentation using implants coated with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7 (rhBMP-7/rhOP-1): histological observations. J Clin Periodontol 2010, 37 (6), 574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laird NZ; Malkawi WI; Chakka JL; Acri TM; Elangovan S; Salem AK, A proof of concept gene-activated titanium surface for oral implantology applications. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2020, 14 (4), 622–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atluri K; Lee J; Seabold D; Elangovan S; Salem AK, Gene-Activated Titanium Surfaces Promote In Vitro Osteogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2017, 32 (2), e83–e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vervaeke S; Collaert B; Cosyn J; Deschepper E; De Bruyn H, A multifactorial analysis to identify predictors of implant failure and peri-implant bone loss. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2015, 17 Suppl 1, e298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer K; Stenberg T, Prospective 10-year cohort study based on a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on implant-supported full-arch maxillary prostheses. Part 1: sandblasted and acid-etched implants and mucosal tissue. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2012, 14 (6), 808–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanoff C-J; Widmark G; Johansson C; Wennerberg A, Histologic evaluation of bone response to oxidized and turned titanium micro-implants in human jawbone. The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants 2003, 18, 341–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pecora G; Ceccarelli R; Bonelli M; Alexander H; Ricci J, Clinical Evaluation of Laser Microtexturing for Soft Tissue and Bone Attachment to Dental Implants. Implant dentistry 2009, 18, 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terheyden H; Lang NP; Bierbaum S; Stadlinger B, Osseointegration--communication of cells. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012, 23 (10), 1127–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao G; Schwartz Z; Wieland M; Rupp F; Geis-Gerstorfer J; Cochran DL; Boyan BD, High surface energy enhances cell response to titanium substrate microstructure. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2005, 74A (1), 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morra M, Biochemical modification of titanium surfaces: peptides and ECM proteins. Eur Cell Mater 2006, 12, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaishya R; Mitra AK, Future of sustained protein delivery. Therapeutic delivery 2014, 5 (11), 1171–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baden LR; El Sahly HM; Essink B; Kotloff K; Frey S; Novak R; Diemert D; Spector SA; Rouphael N; Creech CB, Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. New England journal of medicine 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polack FP; Thomas SJ; Kitchin N; Absalon J; Gurtman A; Lockhart S; Perez JL; Marc GP; Moreira ED; Zerbini C, Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batty CJ; Heise MT; Bachelder EM; Ainslie KM, Vaccine formulations in clinical development for the prevention of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2021, 169, 168–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah SM; Alsaab HO; Rawas-Qalaji MM; Uddin MN, A Review on Current COVID-19 Vaccines and Evaluation of Particulate Vaccine Delivery Systems. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9 (10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasper JC; Schaffert D; Ogris M; Wagner E; Friess W, Development of a lyophilized plasmid/LPEI polyplex formulation with long-term stability—A step closer from promising technology to application. Journal of controlled release 2011, 151 (3), 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeifer C; Hasenpusch G; Uezguen S; Aneja MK; Reinhardt D; Kirch J; Schneider M; Claus S; Frieß W; Rudolph C, Dry powder aerosols of polyethylenimine (PEI)-based gene vectors mediate efficient gene delivery to the lung. Journal of Controlled Release 2011, 154 (1), 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzeng SY; Guerrero-Cázares H; Martinez EE; Sunshine JC; Quiñones-Hinojosa A; Green JJ, Non-viral gene delivery nanoparticles based on Poly(β-amino esters) for treatment of glioblastoma. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (23), 5402–5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Intra J; Salem AK, Characterization of the transgene expression generated by branched and linear polyethylenimine-plasmid DNA nanoparticles in vitro and after intraperitoneal injection in vivo. Journal of Controlled Release 2008, 130 (2), 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasper JC; Troiber C; Küchler S; Wagner E; Friess W, Formulation development of lyophilized, long-term stable siRNA/oligoaminoamide polyplexes. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2013, 85 (2), 294–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowe JH; Spargo BJ; Crowe LM, Preservation of dry liposomes does not require retention of residual water. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1987, 84 (6), 1537–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter JF; Chang BS; Garzon-Rodriguez W; Randolph TW, Rational design of stable lyophilized protein formulations: theory and practice. Rational design of stable protein formulations 2002, 109–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anchordoquy TJ; Koe GS, Physical stability of nonviral plasmid-based therapeutics. J Pharm Sci 2000, 89 (3), 289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saher O; Lehto T; Gissberg O; Gupta D; Gustafsson O; Andaloussi SE; Darbre T; Lundin KE; Smith C; Zain R, Sugar and Polymer Excipients Enhance Uptake and Splice-Switching Activity of Peptide-Dendrimer/Lipid/Oligonucleotide Formulations. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11 (12), 666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crowe JH; Leslie SB; Crowe LM, Is vitrification sufficient to preserve liposomes during freeze-drying? Cryobiology 1994, 31 (4), 355–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison SD; Marion d CM; Thomas JA, Stabilization of lipid/DNA complexes during the freezing step of the lyophilization process: the particle isolation hypothesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2000, 1468 (1), 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng-Lund H; Holm TP; Poso A; Jorgensen L; Rantanen J; Grohganz H, Exploring the chemical space for freeze-drying excipients. International journal of pharmaceutics 2019, 566, 254–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holm TP; Meng-Lund H; Rantanen J; Jorgensen L; Grohganz H, Screening of novel excipients for freeze-dried protein formulations. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2021, 160, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elangovan S; D’Mello SR; Hong L; Ross RD; Allamargot C; Dawson DV; Stanford CM; Johnson GK; Sumner DR; Salem AK, The enhancement of bone regeneration by gene activated matrix encoding for platelet derived growth factor. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (2), 737–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Mello S; Salem AK; Hong L; Elangovan S, Characterization and evaluation of the efficacy of cationic complex mediated plasmid DNA delivery in human embryonic palatal mesenchyme cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2016, 10 (11), 927–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song JH; Record DW; Broderick KB; Sundstrom CE, Method of controlling release of sucralose in chewing gum using cellulose derivatives and gum produced thereby. Google Patents: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bubník Z; Kadlec P, Sucrose solubility. In Sucrose: Properties and Applications, Mathlouthi M; Reiser P, Eds. Springer US: Boston, MA, 1995; pp 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dürig T; Karan K, Chapter 9 - Binders in Wet Granulation. In Handbook of Pharmaceutical Wet Granulation, Narang AS; Badawy SIF, Eds. Academic Press: 2019; pp 317–349. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moret I; Esteban Peris J; Guillem VM; Benet M; Revert F; Dasí F; Crespo A; Aliño SF, Stability of PEI-DNA and DOTAP-DNA complexes: effect of alkaline pH, heparin and serum. J Control Release 2001, 76 (1–2), 169–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khorsand B; Nicholson N; Do A-V; Femino JE; Martin JA; Petersen E; Guetschow B; Fredericks DC; Salem AK, Regeneration of bone using nanoplex delivery of FGF-2 and BMP-2 genes in diaphyseal long bone radial defects in a diabetic rabbit model. Journal of Controlled Release 2017, 248, 53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ando S; Putnam D; Pack DW; Langer R, PLGA microspheres containing plasmid DNA: preservation of supercoiled DNA via cryopreparation and carbohydrate stabilization. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 1999, 88 (1), 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowers KT; Keller JC; Randolph BA; Wick DG; Michaels CM, Optimization of surface micromorphology for enhanced osteoblast responses in vitro. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1992, 7 (3), 302–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider GB; Zaharias R; Seabold D; Keller J; Stanford C, Differentiation of preosteoblasts is affected by implant surface microtopographies. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2004, 69A (3), 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohammed-Saeid W; Michel D; El-Aneed A; Verrall RE; Low NH; Badea I, Development of lyophilized gemini surfactant-based gene delivery systems: influence of lyophilization on the structure, activity and stability of the lipoplexes. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2012, 15 (4), 548–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schliephake H; Scharnweber D, Chemical and biological functionalization of titanium for dental implants. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2008, 18 (21), 2404–2414. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tran C; Walsh LJ, Novel models to manage biofilms on microtextured dental implant surfaces. Microbial Biofilms—Importance and Applications; Dhanasekaran D, Thajuddin N, Eds 2016, 463–486. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marsh PD; Devine DA, How is the development of dental biofilms influenced by the host? J Clin Periodontol 2011, 38, 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Souza J; Henriques M; Oliveira R; Teughels W; Celis J-P; Rocha L, Do oral biofilms influence the wear and corrosion behavior of titanium? Biofouling 2010, 26 (4), 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giacaman RA; Campos P; Muñoz-Sandoval C; Castro RJ, Cariogenic potential of commercial sweeteners in an experimental biofilm caries model on enamel. Archives of Oral Biology 2013, 58 (9), 1116–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young DA; Bowen WH, The influence of sucralose on bacterial metabolism. J Dent Res 1990, 69 (8), 1480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu J; Liu J; Li Z; Xi R; Li Y; Peng X; Xu X; Zheng X; Zhou X, The Effects of Nonnutritive Sweeteners on the Cariogenic Potential of Oral Microbiome. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 9967035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]