Maintenance of lipid homeostasis is essential for cell growth and survival and can be dysregulated in disease [1]. Mammalian cells acquire lipids through both synthesis and uptake from the environment where lipids principally circulate in blood as lipoproteins and free fatty acids bound to albumin [2]. Experiments examining the regulation of lipid homeostasis routinely culture cells in lipoprotein-deficient serum (LDPS) to eliminate the supply of extracellular lipids [3]. LPDS can either be prepared in house or obtained from two commercial sources (Millipore Sigma or Kalen Biomedical)[4]. Published protocols for preparing LPDS from fetal bovine serum (FBS) use ultracentrifugation in potassium bromide gradients to remove lipoproteins followed by dialysis [4].

Recently, we characterized the adaptive transcriptional response of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (Pa03c) cells to low lipid conditions by measuring gene expression in cells cultured in FBS or LPDS. The LPDS serum was obtained from Sigma and derived from the paired FBS serum. In addition to observing changes in target genes for sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) transcription factors as expected [5], we unexpectedly observed upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) target genes and described a mechanism by which lipoproteins regulate HIF [6]. Notably, we also observed upregulation by microarray of TFRC, which codes for transferrin receptor, when cells were cultured in LPDS compared to FBS [6], suggesting that iron homeostasis may be altered in LPDS.

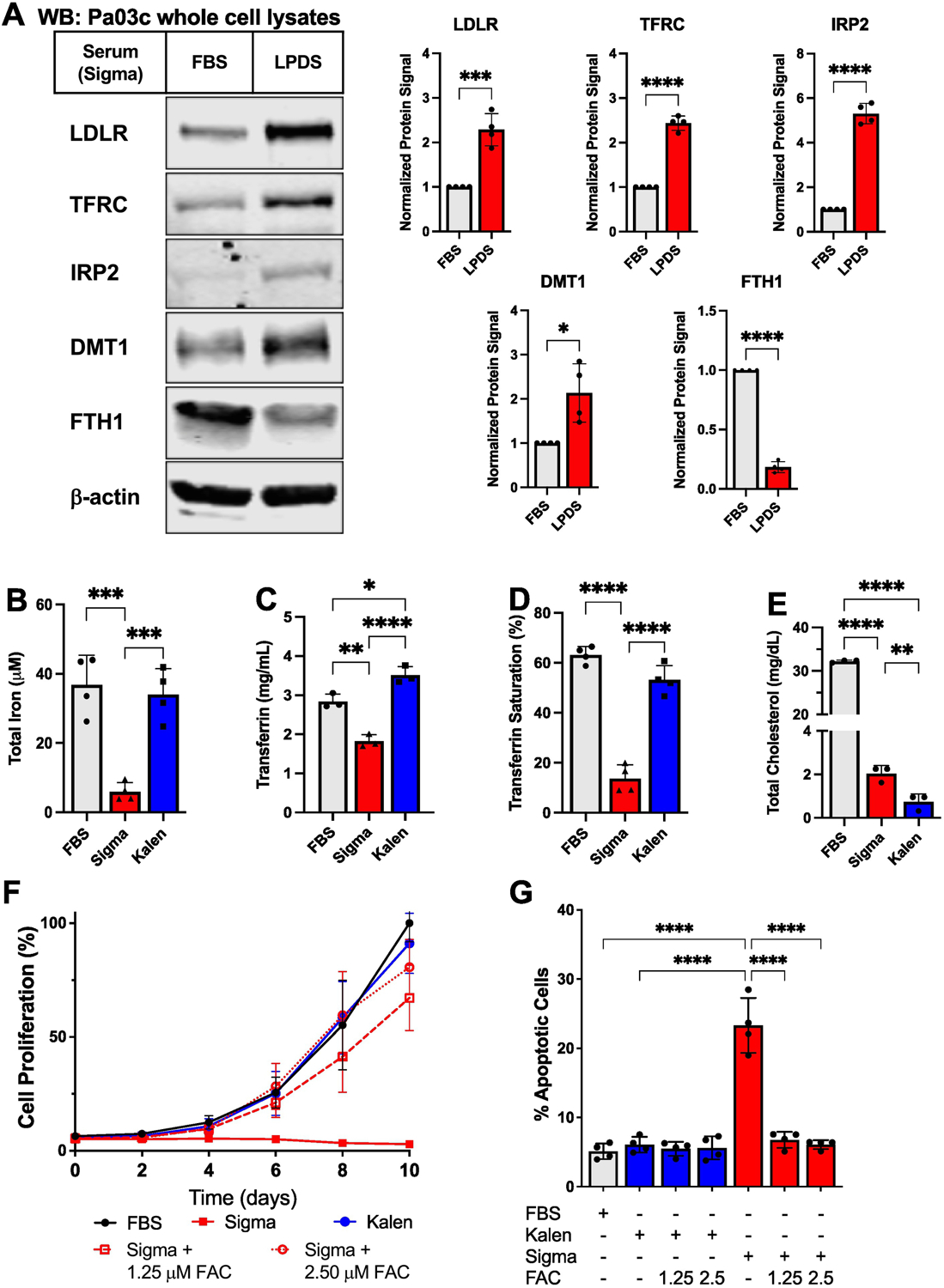

Iron homeostasis is primarily regulated post-transcriptionally through the iron response protein IRP2 [7]. IRP2 binds to iron response elements in mRNAs of iron homeostasis genes to promote translation of genes responsible for iron uptake such as TFRC and DMT1, a membrane iron transporter found on the plasma membrane as well as the lysosome, and to downregulate expression of genes involved in iron export and iron storage. Intracellular iron regulates the stability of IRP2 protein [7]. In the presence of iron, IRP2 is ubiquitinylated by FBXL5, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and degraded by the proteasome. In the absence of iron, FBXL5 itself is degraded, resulting in increased IRP2 levels. To explore whether culturing cells in LPDS affects iron homeostasis, we analyzed protein expression by western blotting in cells cultured in either FBS or LPDS (Fig. 1A). Expression of IRP2, TFRC, and DMT1 was upregulated in LPDS compared to FBS while expression of FTH1, which is the heavy chain of the iron storage complex ferritin, was downregulated. As expected, LDLR was upregulated in LPDS in response to low lipid conditions. Collectively, protein expression data indicate that culturing Pa03c cells in LPDS promotes an iron starvation response.

Figure 1. Commercial lipoprotein-deficient sera differ in iron content.

(A) Pa03c cells (3×106) were seeded in 10 cm dishes for two days before being cultured for 24 hours in 10% FBS or 10% Sigma LPDS. Indicated proteins were detected by immunoblotting (WB). β-actin served as a loading control. Representative blots of 4 biological replicates are shown. Quantification of 4 experiments is shown at right. Antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology [TFRC (#13113), IRP2 (#37135), DMT1 (#15083), FTH1(4393)], Proteintech (LDLR (#10785–1-AP), or Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Actin, sc-47778). Bars represent mean +/− SD. (B-E) Sigma LPDS-matched FBS, Sigma LPDS, and Kalen LPDS sera were analyzed for total iron (B), total transferrin (C), percent saturation of transferrin (D), and total cholesterol (E). Each component was measured using a commercially available kit: total iron and percent saturation of iron, Pointe Scientific Iron/TIBC Reagents (I7504–60); transferrin concentration, Eagle Biosciences Bovine Transferrin ELISA Assay (BTF61-K01); and total cholesterol, Wako Diagnostics Cholesterol E kit (999–02601). Each kit was used according to manufacturer’s protocols. Bars represent mean +/− SD. n = 3 biological replicates for cholesterol and transferrin concentration assays. n = 4 biological replicates for total iron and transferrin saturation assays. (F) Pa03c cells (2×103) were plated in 96-well plates on day −1 and incubated for 24 hours. On day 0, media was replaced, and cells were cultured in the indicated serum in the absence or presence of ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) for 10 days. Cell proliferation was measured every 2 days by MTS assay (Promega G3580). Points represent mean +/− SD of 3 biological replicates. (G) Pa03c cells (2×105) were plated in 6-well plates on day 0. On day 1, media was replaced, and cells were cultured for 2 days in the indicated conditions. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide and annexin-V using the ThermoFisher Scientific Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (#V13242) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells that stained positive for annexin-V were considered apoptotic cells, and the percentage of this population in the total cell population was recorded. Bars represent mean +/− SD of n = 4 biological replicates. Appropriate statistical tests (student’s t-tests or one-way ANOVAs) were used for analysis using GraphPad Prism. P-values are as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p <0.0001.

To explore why LPDS serum promoted the iron starvation response, we determined the composition of FBS and LPDS sera from Sigma. Surprisingly, we found that LPDS contained approximately 15% of the iron compared to FBS (Fig. 1B). To determine if iron content is commonly reduced in other sources of LPDS, we tested the composition of LPDS supplied by Kalen Biosciences. The iron content of Kalen LPDS was similar to Sigma FBS (Fig. 1B). Usually, serum iron does not exist as free iron, but rather iron is bound to the transport protein transferrin [8]. We next determined the transferrin concentration in these three sera and observed a significant decrease in the amount of transferrin in Sigma LPDS compared to Sigma FBS and Kalen LPDS (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the transferrin in Sigma LPDS contained less iron as the percent saturation of Sigma LPDS was approximately 5-fold less than Sigma FBS or Kalen LPDS (Fig. 1D). Kalen LPDS contained slightly more transferrin than Sigma FBS, but there was no significant difference in transferrin iron saturation. Noticing these differences, we wanted to confirm that these lipoprotein-deficient sera were depleted of cholesterol. Sigma LPDS and Kalen LPDS contained approximately 16-fold and 40-fold less cholesterol, respectively, compared to Sigma FBS (Fig. 1E). Protein concentration of these sera was measured, and no difference was observed among the three sera. Finally, the differences in sera composition, total iron and transferrin saturation, were observed across different lots. Thus, the two principal commercial sources of LPDS are both cholesterol-depleted but differ dramatically in iron content.

Iron is an essential metal for all cells and is required for cell signaling, metabolism, and proliferation [9, 10]. Given the observed differences in iron composition of these commercial LPDS, we next tested how these different sera supported cell growth. Cells grown in Sigma FBS and Kalen LPDS grew at a similar rate over a 10-day experiment, but cells grown in Sigma LPDS failed to grow and even decreased in number over time (Fig 1F). To determine if this decreased cell growth was due to the reduced iron in Sigma LPDS, we supplemented media with two different concentrations of ferric ammonium citrate (FAC). Addition of FAC rescued growth of Pa03c cells in Sigma LPDS in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1F), and addition of 2.5 μM FAC restored growth to that of Sigma FBS and Kalen LPDS. Thus, iron is limiting for cell growth in Sigma LPDS.

As noted, cell numbers decreased over time in Sigma LPDS. To test whether the decrease is due to cell death, we measured apoptosis in cells cultured for 2 days under the same conditions. Cells grown in Sigma FBS or Kalen LPDS had similar levels of apoptotic cells (~5%), and adding iron to Kalen LPDS had no effect on apoptosis (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, cells grown in Sigma LPDS had 4 to 5-fold higher levels of apoptotic cells (~23%) compared to cells grown in matched Sigma FBS or Kalen LPDS. Adding FAC to Sigma LPDS rescued cell viability and restored levels of apoptosis to baseline (Fig. 1G). Collectively, these experiments demonstrate that compared to matched Sigma FBS and Kalen LPDS, Sigma LPDS is iron-deficient due to reduced levels of transferrin and transferrin saturation, and this serum fails to support short and long-term growth of cells.

It has been shown previously that differences in ultracentrifugation protocols can affect sample composition using patient blood samples [11]. While purely speculative as we were unable to acquire preparation methods from the suppliers, it is possible that preparation protocols differed at the ultracentrifugation step in LPDS production. Variations in centrifugation speed or time may have led to the loss of iron in the Sigma LPDS. Iron binding to transferrin is sensitive to pH [7]. At neutral pH, iron is strongly bound to transferrin. However, as transferrin travels through the endocytic pathway, it is exposed to increasingly acidic environments, and iron is released for utilization by the cell. Differences in the pH of buffers used or centrifugation protocols may have created enough of an acidic environment in the Sigma LPDS that iron was released from transferrin. As the sera was then dialyzed, iron may have been lost leading to the ultimate decrease in total iron present.

With the options for commercial LPDS limited, we have identified an important difference between two commercially available sera that can dramatically impact experimental results. We initially identified an iron starvation signature by western blotting and further demonstrated that Sigma LPDS was significantly depleted of transferrin and iron compared to matched Sigma FBS and Kalen LPDS. Experiments employing Sigma LPDS should be reexamined to see whether iron starvation influenced observed results. Lastly, these observations emphasize the importance of carefully validating reagents to promote rigor in scientific research.

Highlights.

Lipoprotein-deficient serum from Sigma is iron depleted and activates the iron starvation response.

Addition of iron to lipoprotein-deficient serum from Sigma suppressed apoptosis and restored cultured cell growth.

Funding and Acknowledgements:

This project was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01 GM126088 (P.J.E.) and T32 GM007445 (J.M.L.). The sponsor had no role in the design, execution, and submission of this research. We thank Stephanie Myers for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Snaebjornsson MT, Janaki-Raman S, Schulze A, Greasing the wheels of the cancer machine: The role of lipid metabolism in cancer, Cell Metab, 31 (2020) 62–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vance DE, Vance JE, Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes, 4th ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brown MS, Dana SE, Goldstein JL, Regulation of 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme A reductase-activity in cultured human fibroblasts - Comparison of cells from a normal subject and from a patient with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, J Biol Chem, 249 (1974) 789–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goldstein JL, Basu SK, Brown MS, Receptor-mediated endocytosis of low-density lipoprotein in cultured cells, Methods Enzymol, 98 (1983) 241–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shao W, Espenshade PJ, Expanding roles for SREBP in metabolism, Cell Metab, 16 (2012) 414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shao W, Hwang J, Liu C, Mukhopadhyay D, Zhao S, Shen MC, Alpergin ESS, Wolfgang MJ, Farber SA, Espenshade PJ, Serum lipoprotein-derived fatty acids regulate hypoxia-inducible factor, J Biol Chem, 295 (2020) 18284–18300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pantopoulos K, Porwal SK, Tartakoff A, Devireddy L, Mechanisms of mammalian iron homeostasis, Biochemistry, 51 (2012) 5705–5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Muckenthaler MU, Rivella S, Hentze MW, Galy B, A red carpet for iron metabolism, Cell, 168 (2017) 344–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kaplan J, Ward DM, The essential nature of iron usage and regulation, Curr Biol, 23 (2013) 2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weber RA, Yen FS, Nicholson SPV, Alwaseem H, Bayraktar EC, Alam M, Timson RC, La K, Abu-Remaileh M, Molina H, Birsoy K, Maintaining iron homeostasis is the key role of lysosomal acidity for cell proliferation, Mol Cell, 77 (2020) 645–655 e647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lesche D, Geyer R, Lienhard D, Nakas CT, Diserens G, Vermathen P, Leichtle AB, Does centrifugation matter? Centrifugal force and spinning time alter the plasma metabolome, Metabolomics, 12 (2016) 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]