Abstract

Purpose:

Targeting focal adhesion kinase (FAK) renders checkpoint immunotherapy effective in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) mouse model. Defactinib is a highly potent oral FAK inhibitor that has tolerable safety profile.

Experimental design:

We conducted a multicenter, open-label, phase 1 study with dose escalation and expansion phases. In dose escalation, patients with refractory solid tumors were treated at five escalating dose levels of defactinib and gemcitabine to identify a recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D). In expansion phase, patients with metastatic PDAC who progressed on frontline treatment (refractory cohort) or had stable disease (SD) after at least 4 months of standard gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (maintenance cohort) were treated at RP2D. Pre- and post-treatment tumor biopsies were performed to evaluate tumor-immunity.

Results:

The triple drug combination was well-tolerated with no dose-limiting toxicities. Among 20 treated patients with refractory PDAC, the disease control rate (DCR) was 80% with one partial response (PR) and fifteen SDs and the median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 3.6 months and 7.8 months, respectively. Among 10 evaluable patients in the maintenance cohort, DCR was 70% with one PR and six SD. Three patients with SD came off study due to treatment or disease-related complications. The median PFS and OS on study treatment were 5.0 months and 8.3 months, respectively.

Conclusions:

The combination of defactinib, pembrolizumab, and gemcitabine was well-tolerated and safe, had promising preliminary efficacy and showed biomarker activity in infiltrative T lymphocytes. Efficacy of this strategy may require incorporation of more potent chemotherapy in future studies.

Keywords: Focal-adhesion kinase, pancreas cancer, immunotherapy, defactinib

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains highly lethal with no effective systemic treatment options other than combination chemotherapies, which are palliative, typically with short-lived treatment response and with considerable toxicities(1,2). The benefit of immune or targeted therapies is limited to a small subset of patients with known tumor-specific or germline mutations. For instance, checkpoint immunotherapies, including antagonists against programed cell dealth-1 (PD-1) or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 are only beneficial to ~0.8% of patients with mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) or microsatellite stability (MSS) disease(3–5). Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors such as olaparib serves a non-chemotherapy option for PDAC patients with germline breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA-1) and BRCA-2 mutations after disease stabilization with platinum-based chemotherapy such as FOLFIRINOX (cocktail of folinic acid, irinotecan, oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil) (6,7). Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies that can enhance and prolong treatment response with minimal side effects are direly needed.

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a tyrosine kinase regulating multiple cellular functions, in particular cellular organization, such as adhesion and migration(8,9). FAK is hyperactivated in the majority of PDAC, and its level of activation is associated with poor prognosis(10). In preclinical PDAC mouse models, pharmacologic FAK inhibition results in delayed tumor growth and better survival, and the anti-tumor effect is boosted when combined with anti-PD1 and gemcitabine(10). Mechanistically, FAK inhibition resulted in decreased tumor desmoplasia and tumor-associated macrophages and increased influx of cytotoxic T cell infiltration(10,11). Similarly, FAK’s immune-suppressive effects on the tumor microenvironment have been reported in other tumor types, including squamous cell carcinoma(8). Defactinib (VS-6063, Verastem, MA) is a potent and safe, orally administered small molecule FAK inhibitor which directly competes for the ATP-binding site(12–14). Here, we present the safety, preliminary efficacy, and biomarker data for the triple drug combination of defactinib, pembrolizumab, and gemcitabine in advanced solid tumors, focusing on PDAC.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted an open-label, phase I study, which included a dose escalation and a dose expansion at Washington University in St. Louis and Mayo Clinic in Rochester (Supplemental Table 1 and 2), to determine the safety of a combination of defactinib, pembrolizumab, and gemcitabine in patients (≥ 18 years of age) with histologically confirmed advanced solid tumors (dose escalation cohort) or advanced PDAC (dose expansion cohort). The one dose expansion cohort (refractory cohort) included advanced PDAC patients, who progressed with at least one line of systematic therapy for advanced disease. The second expansion cohort (maintenance cohort) enrolled PDAC patients who achieved a treatment response or stable disease after at least 4 months of frontline therapy of gemcitabine and Abraxane (G/A). Toxicity assessment was performed on all treated patients, regardless of evaluability of treatment response. Treated patients who received imaging scans prior to the first planned assessment (after 3 cycles) due to clinical suspicion of progression were deemed evaluable. Patients who came of study prior to any imaging evaluation to document disease status were included in survival analyses if deemed to be related to clinical disease progression. Measurable disease, defined as lesions ≥ 10 mm with a computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging, ≥ 20 mm by chest x-rays, or ≥ 10 mm with calipers by clinical exam, was required. Additionally, patients were deemed eligible if they had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of ≤ 1 and a life expectancy of at least 3 months. Patients who had received prior FAK inhibitors or anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, anti-PD-L2, anti-CD137, or anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 antibody were ineligible, as were patients with brain metastasis. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki statement on ethical biomedical research and with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Boards for each study site and registered at clinical trial.gov as NCT02546531. All patients provided written informed consent. Patient cohort demographic data are in Supplemental Table 1 and 2.

Procedures

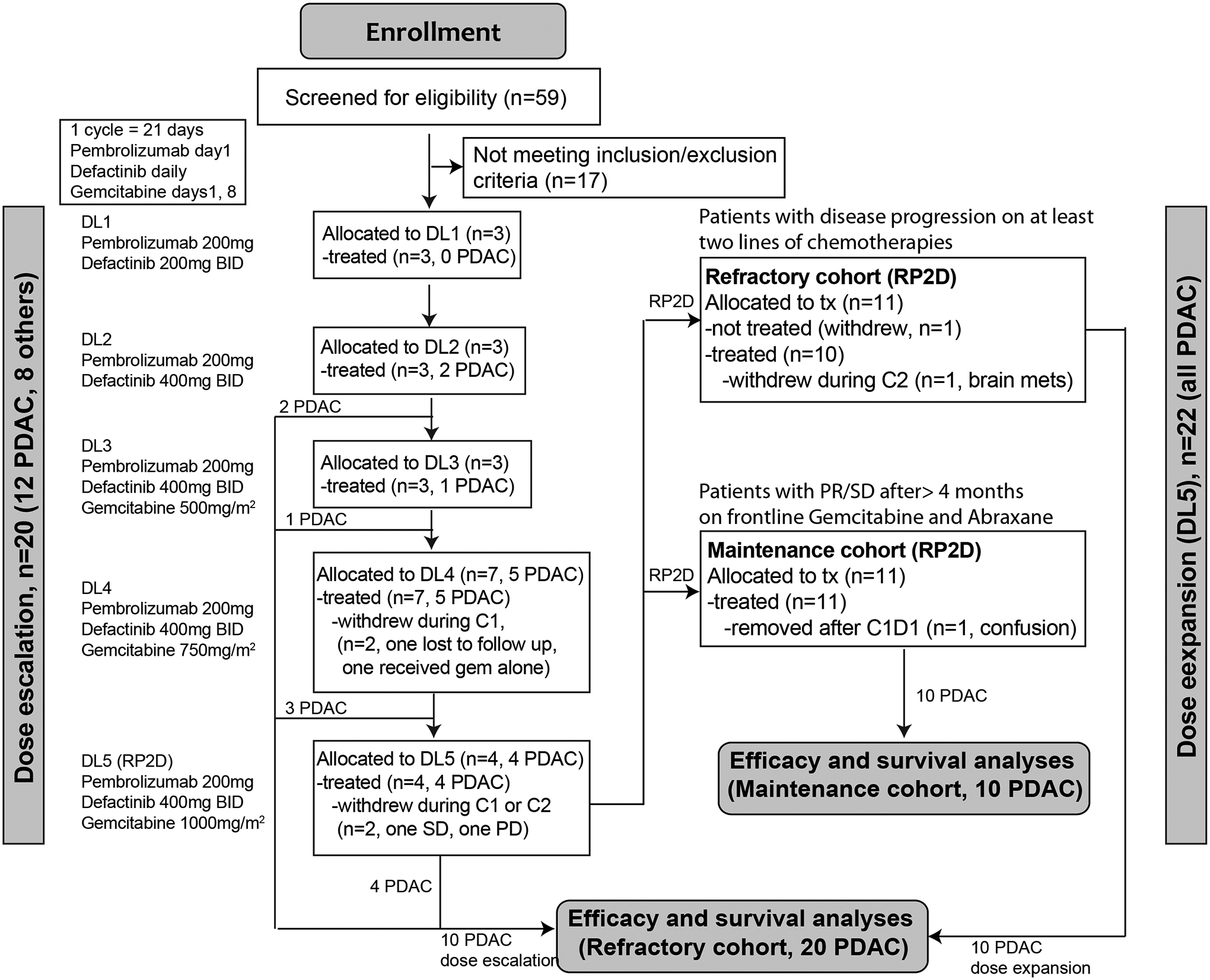

Dose escalation was conducted using a two-stage design. A small cohort of 3 patients were treated at the initial dose level. If no DLT was observed, the next cohort was assigned to a higher dose level. As soon as the first DLT is observed, three additional patients were enrolled. For the dose escalation cohort, defactinib was started at twice per day at either a 200mg BID or 400mg BID on a 21-day cycle. Pembrolizumab (200mg) was given intravenously every 21 days. Gemcitabine was not given to the first two dose levels and was administered on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle at 500mg/m2, 750mg/m2, or 1,000mg/m2 for dose levels 3, 4, or 5, respectively (Figure 1). The recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) was determined to be defactinib 400mg BID D1–21, pembrolizumab 200mg D1, and gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 D1 and D8, every 21 days. Toxicities were assessed according to CTCAE 4.0, and the treatment response was evaluated every 3 cycles per RECIST 1.1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of patients enrolled in this study.

Clinical outcomes measures

The primary endpoint was to assess the safety and toxicity profile of the triple-drug regimen and determine the MTD or RP2D. The secondary endpoints included objective response rate (ORR), time on treatment, PFS and OS, which were described using Kaplan-Meier product limit method. The exploratory endpoints were to assess biomarkers associated with treatment response and resistance.

Multi-parametric flow cytometry of biopsy tissues

Biopsy tissues were collected from the endoscopy suite and placed in DMEM on wet ice prior to processing. Human tumor samples were digested in HBSS supplemented with 2mg/mL collagenase A (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), 2.5U/mL hyaluronidase, and DNase I at 37°C for 30 min with agitation to generate single cell suspensions. Following tissue digestion, single cell suspensions were resuspended in flow cytometry buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 5 mM EDTA), FcR blocked with human TruStain FcX (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for 10 min, and pelleted by centrifugation. When applicable, live/dead viability dyes were used for 15–30 min at room temperature prior to centrifugation. The cells were consequently labeled with 200 μL of fluorophore-conjugated anti-human extracellular antibodies at recommended dilutions for 30 min on ice. Intracellular staining for transcription factors and intracellular markers was subsequently employed using the eBioscience Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry data were acquired using BD Fortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) within 7 days and analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10) with application of bead-based post-hoc compensation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) or by a biostatistics core expert at Washington University using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institutes, Cary, NC). Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), unless otherwise noted. Normal distribution of data was assessed using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test in Prism (GraphPad). For survival analyses, the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used. For proximity analyses, the nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to distinguish differences in frequency distributions.

Data Availability.

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Results

Totally 59 patients were screed and 42 eligible patients were enrolled and treated in two phases: dose escalation (n=20) and expansion phase (n=22, Figure 1). Of the 20 patients treated in the dose escalation, 12 (60%) had refractory PDAC who had progressed on frontline chemotherapy. The median age was 62 years, and the median number of prior systemic treatments was two lines. All 22 patients enrolled in the dose expansion phase had PDAC. In this portion, 11 patients had PDAC which had progressed on one to three different combination chemotherapies (refractory cohort), and 11 with stable disease after at least 4 months of frontline Gemcitabine plus Abraxane (or nab-paclitaxel, G/A, maintenance cohort). None of the patients with tumor tested with next-generation sequencing (NGS) had were microsatellite unstable or high tumor mutational burden (TMB) disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics

| All patients | Dose escalation (n=20) | Dose expansion (n=22) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62 (46–75) | 64 (35–84) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 13 (65%) | 12 (54%) |

| Male | 7 (35%) | 10 (46%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 16 (80%) | 20 (91%) |

| Black | 3 (15%) | 0 |

| Others | 1 (5%) | 2 (9%) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 5 (25%) | 3 (14%) |

| 1 | 15 (75%) | 19 (86%) |

| Histology | ||

| PDAC | 12 (60%) | 22 (100%) |

| Biliary | 3 (15%) | |

| Others | 5 (25%) | |

| PDAC patients | PDAC patients (n=12) | PDAC patients (n=22) Refractory cohort (n=11) Maintenance cohort (n=11) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 12 (100%) | 22 (100%) |

| Median prior lines of therapy (range) | 2 (1–7) | Refractory cohort: 2 (1–3) Maintenance cohort: 1 |

| Pretreatment labs | ||

| Albumin (>3.5gm/dL) | 12 (100%) | 22 (100%) |

| CA 19–9 (>35 U/mL) | 9 (75%) | 18 (82%) |

| Prior surgery for PDAC | 4 (20%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| Extend of disease | ||

| Clinical stage IV | 20 (100%) | 22 (100%) |

| Lung | 6 (50%) | 8 (37%) |

| Liver | 6 (50%) | 15 (68%) |

| Lymph nodes | 2 (16%) | 4 18%) |

| Bone | 1 (8%) | 2 (9%) |

| Muscle | 2 (16%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| Peritoneal cavity | 1 (8%) | 3 (14%) |

| Tumor NGS | ||

| Available | 6 (50%) | 15 (68%) |

| MSS/dMMR | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| TMB-high | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Toxicity assessment.

In the dose escalation phase, all five dose levels (DL) were well-tolerated by study participants. No dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) or treatment-related death was observed (Table 2). The recommended phase two dose (RP2D) was defactinib 400mg BID, pembrolizumab 200mg on day 1, and gemcitabine 1,000mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of a 3-week cycle. The most common treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were fatigue (65%), anorexia (43%), neutropenia (57%), anemia (57%), thrombocytopenia (35%), nausea (52%), vomiting (39%), and edema (30%). Grade 3 or 4 TRAEs occurring in more than 10% of patients included neutropenia (39%) and anemia (17%). Immune-related adverse events included one case of mild, self-limited pancreatitis which was attributed possibly to defactinib or pembrolizumab, one case of mild hypothyroidism attributed to pembrolizumab, and four cases of grade 1 to 2 dyspnea secondary to pneumonitis which were attributed to all agents. All these four patients recovered after temporary treatment break without requiring the use of steroids, and none had recurrence after treatment rechallenge.

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events (including >10% for all grades, and all grade 3/4)

| Dose escalation (n=20) | Dose expansion (RP2D), n=22 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL1, n=3 | DL2, n=3 | DL3, n=3 | DL4, n=7 | DL5 (RP2D), n=4 | ||||||||

| G 3/4 | All | G 3/4 | All | G 3/4 | All | G 3/4 | All | G 3/4 | All | G3/4 | All | |

| Constitutional | ||||||||||||

| Anorexia | 0 | 2 (67%)p,d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p,d,g | 0 | 1 (14%)g | 0 | 1 (25%)g | 0 | 10 (43%)p,d,g |

| Weakness | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p,d | 1 (33%)p,d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1 (33%)p,d | 2 (67%)p,d | 0 | 1 (33%)p,d | 0 | 2 (67%)p,d,g | 0 | 2 (29%)g | 1 (25%)d | 3 (75%)p,d,g | 1 (4%)p,d,g | 15 (65%) p,d,g |

| Edema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25%)g | 0 | 7 (30%)p,d,g |

| Fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)g | 0 | 2 (29%)d,g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (17%) p,d,g |

| Myalgia | 0 | 1 (33%)p,d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9%)p |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p | 1 (33%)p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%)p,g | 0 | 1 (25%)d | 0 | 1 (4%)p |

| Hematologic | ||||||||||||

| Neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%)g | 2 (29%)g | 1 (25%)p,d,g | 1 (25%)p,d,g | 9 (39%)p,d,g | 13 (57%) p,d,g |

| Leukopenia | 1 (33%)d,g | 1 (33%)d,g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (57%)g | 0 | 2 (50%)g | 0 | 6 (26%) p,d,g |

| Anemia | 0 | 1 (33%)g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (43%)g | 0 | 3 (75%)g | 4 (17%)p,d,g | 13 (57%)p,d,g |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)g | 1 (33%)g | 0 | 2 (29%)g | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)g | 8 (35%) p,d,g |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||||||||

| Nausea | 0 | 2 (67%)p,d | 0 | 1 (33%)p | 0 | 2 (67%)p,d,g | 0 | 2 (29%)g | 0 | 1 (25%)g | 0 | 12 (52%) p,d,g |

| Vomiting | 0 | 2 (67%)p,d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p,d,g | 0 | 2 (29%)p,d,g | 0 | 1 (25%)g | 2 (9%)p,d,g | 9 (39%) p,d,g |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p,d | 0 | 1 (33%)p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)g | 8 (35%) p,d,g |

| Constipation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p,d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%) p,d,g |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%) p,d,g |

| Mucositis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%)g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9%) p,d,g |

| Pancreatitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)d |

| ALT/ALT increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%)d,g | 1 (14%)d,g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9%) p,d,g |

| Elevated bilirubin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25%)p,g | 1 (4%)p,g | 1 (4%)p,g |

| Renal and electrolytes | ||||||||||||

| Creatinine Increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25%)p,g | 1 (25%)p,g | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)g | 1 (4%)g |

| Hypernatremia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)g |

| Cardiovascular | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9%)p,g | 2 (9%)p,g |

| Heart Failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%) p,d,g | 2 (9%) p,d,g |

| DVT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)p | 1 (4%)p |

| Pulmonary | ||||||||||||

| Pneumonitis with dyspnea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (17%) p,d,g |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)p,d,g |

| Endocrine | ||||||||||||

| Hypothyroidism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33%)p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatologic | ||||||||||||

| Alopecia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (17%) p,d,g |

| Rash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25%)d | 0 | 6 (26%) p,d,g |

| Dry Skin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%) p,d,g |

| Pruritus | 0 | 1 (33%)d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (29%)p,g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%)d |

Attributed to

pembrolizumab,

defactinib or

gemcitabine

Preliminary efficacy.

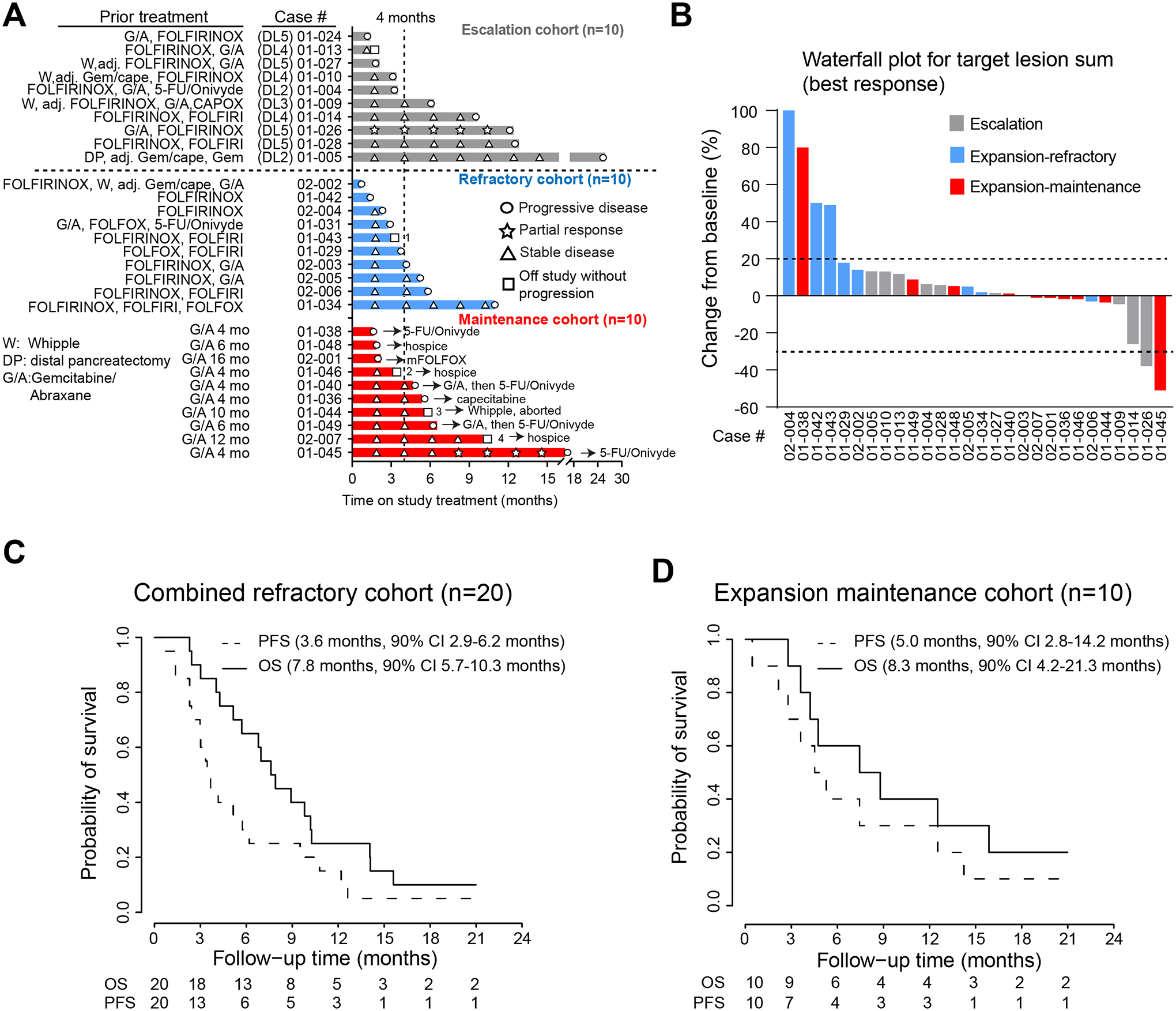

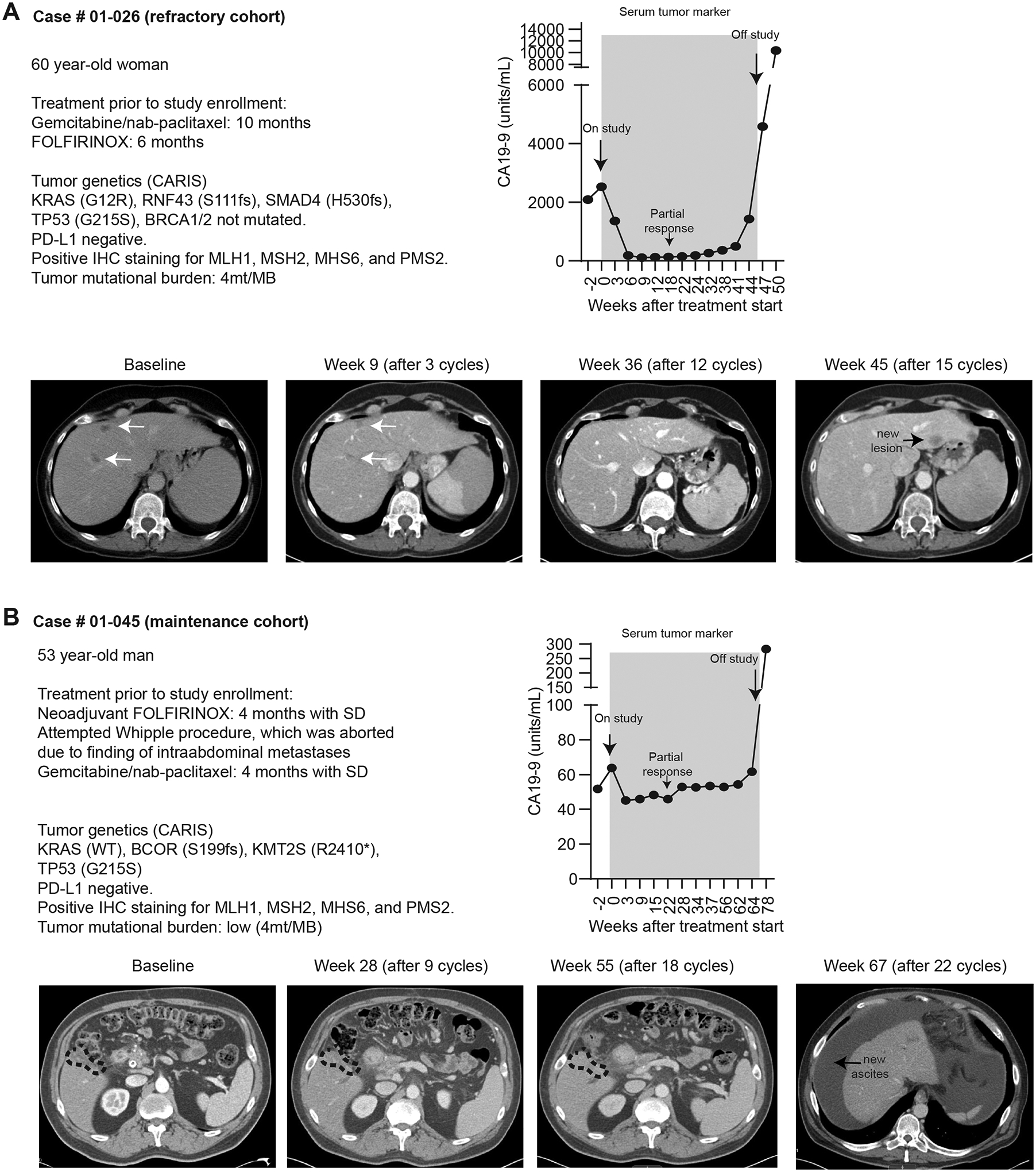

Of twelve PDAC patients enrolled in dose escalation, two patients withdrew during cycle 1 to pursue hospice (DL4, lost to follow up) or gemcitabine monotherapy (DL4, CT later showed SD) and both were excluded from efficacy evaluation. Two patients were removed by treating physicians due to severe fatigue attributed to TRAE (DL5, <1 cycle, CT showed SD) or underlying disease (DL5, < 2 cycles, CT showed PD) and were deemed evaluable. Eight patients underwent planned radiographic assessment after 3 cycles. Of all ten evaluable patients, one patient experienced a partial response (PR), seven had stable disease (SD) and two had PD, resulting in a disease control rate (DCR, equals PR + SD) of 80% (8 out of 10). For the eight patients who underwent planned radiographic assessment, DCR was 87.5% (6 SD, 1 PR, 1 PD, Figure 2A–D). Notably, two patients who previously progressed on gemcitabine stayed on study for more than one year (case#01–005: DL2 stayed on study for >24 months, Figure 3A; case#01–026: DL5 with PR stayed on study for 12 months, Figure 3B). Another patient (case#01–028: DL5) who was gemcitabine-naive stayed on study for 12.4 months (Figure 2A). NGS showed all three patients had MSS or TMB-low disease.

Figure 2.

A) Swimmer plot depicting prior treatment history and time on study for all PDAC patients enrolled in this study. Depicted on the plot are symbols for treatment response during study treatment and subsequent treatment (for maintenance cohort) after coming off study. Patient 1: off study per physician discretion due to severe fatigue and opted for hospice. Patient 2: developed congestive heart failure possibly related to gemcitabine, defactinib and pembrolizumab; Patient 3: Whipple procedure attempted and aborted due to intraoperative finding of liver metastases and later died from postoperative wound infection. Patient 4: poor oral intake despite stable CT scans and pursued hospice. B) Waterfall plot depicting best radiographic response for patients treated in each cohorts. Patients who had imaging studies and came off study prior to planned (post 3 cycle) evaluation per RECIST were included. C) Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the PFS and OS for refractory PDAC patients from dose escalation (n=10) and refractory expansion (n=10). D) Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the PFS and OS for PDAC patients treated in the dose expansion phase as maintenance cohort (n=10).

Figure 3. Characteristics of two patients with partial response.

A-B) Prior treatment history, molecular features of tumors, serum CA19–9 and serial radiographic images of two patients who had radiographic partial response on study.

In the dose expansion refractory cohort (n=11), one patient withdrew to pursue hospice before treatment start and was excluded from efficacy evaluation. Of the remaining ten patients, six had not been treated with a gemcitabine-based regimen before enrollment into our study. Two patients were removed at due to worsening symptoms during cycle 2 and imaging showed PD. The remaining eight patients who underwent planned radiographical assessment after 3 cycles per protocol all had SD. Of all these ten patients, two had PD and eight had SD, leading to an initial DCR of 80% (8 out of 10 treated patients). Because PDAC patients treated at dose escalation phase (n=10) and refractory expansion phase (n=10) both had refractory metastatic PDAC progressed on at least one line of chemotherapy, we combined the efficacy data from these two cohorts to obtain a clearer picture on the benefit of defactinib plus pembrolizumab. Of these 20 patients with refractory disease, the first planned or unplanned imaging showed 4 PD, 1 PR, 15 SD, achieving an initial DCR of 80% (Figure 2B). The median duration of study treatment was 3.2 months (range 0.7 – 12.6 months, Figure 2C).The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.6 months (90% CI 2.9 – 6.2 months), and the median overall survival (OS) was 7.8 months (90% CI 5.7 – 10.3 months).

In the dose expansion maintenance cohort, 11 patients who had SD after at least 4 months of frontline Gemcitabine plus Abraxane (G/A) were enrolled. One patient developed mental confusion on cycle 1 day 1 of study, probably due to premedication including dexamethasone, and subsequently decided to pursue hospice after recovery. This patient was deemed not efficacy-evaluable. Of the remaining 10 evaluable patients, 1 had a delayed PR, 6 continued to have SD and 3 had PD, achieving a DCR of 70% (7 of 10 treated patients, Figure 2A, 2B). The patient (case # 01–0145) with delayed PR stayed on treatment for 16.1 months and had MSS and TMB-low tumor (Figure 3B). Three patients with SD came off study and passed away shortly after due to treatment or disease-related complications including a patient (case#01–046) who developed congestive heart failure possibly related to gemcitabine, defactinib and pembrolizumab; another patient (case#02–007) who struggled with poor oral intake and decided to pursue hospice; and the third patient (case#01–044) underwent Whipple procedure which was aborted due to intraoperative findings of small liver metastases and later died from poor wound healing. The remaining four patients who later progressed on study treatment went on to receive other treatment. The median duration of treatment was 5.0 months (range 1.6 – 15.8 months, Figure 2A). The median PFS and OS since initiation of study treatment were 5.0 months (90% CI 2.8 – 14.2 months) and 8.3 months (90% CI 4.2 – 21.3 months), respectively (Figure 2D). For patients in maintenance cohort, median PFS and OS from initial treatment with G/A was 11.3 months (90% CI 7.9 – 21.7 months) and 20.6 months (90% CI 12.1 – 28.4 months), respectively.

Correlative studies.

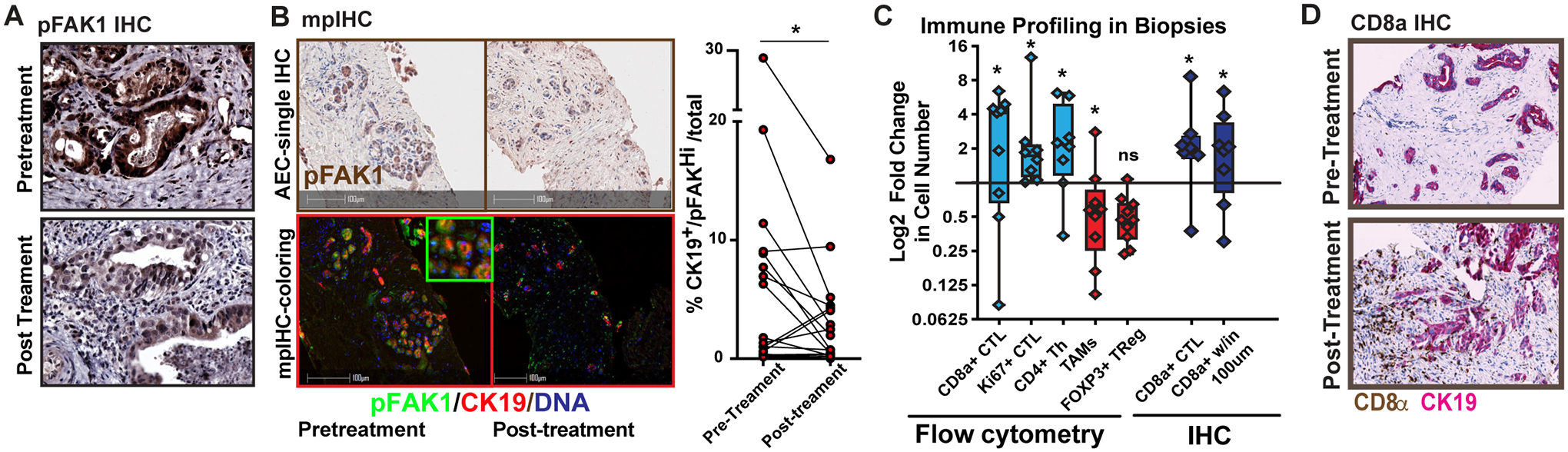

Patients with PDAC in both cohorts underwent needle biopsies of tumor tissues before and after three cycles of therapy, and tumor samples were processed for flow cytometric and immunohistochemistry analysis. Of all collected tissues, nine paired biopsies produced quality flow cytometry data and immunohistochemistry (IHC)/pathology data adequate for meaningful analysis. IHC analysis showed phospho-FAK1 (tyrosine 397), a marker of FAK auto-activation, was decreased in CK19+ PDAC cells in the majority patients biopsies tissues (Figure 4A–B). Assessment of immune cell infiltration was evaluated by flow cytometry and IHC of biopsy tissues. Consistent with preclinical models(10), most post-treatment samples displayed increases in total CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), CD3+CD4+ FOXP3− effector T cells, and pro Ki67+ CD8+ CTLs. In contrast, most patients showed decreased numbers of CD14+CD68+MHCIIHi tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and CD3+CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells. Increases in CD8+ CTLs were verified by IHC, with more marked trends observed in the number of T cells within 100 μm of CK19+ cells (Figure 4C–D). Notably, in this small cohort, no pattern was established between patient outcomes, such as PFS or OS and changes in tumor immunity. Additionally, post-treatment biopsies were not possible in two PR patients due to a decrease in the previously easily accessible metastatic lesions. Together, these data suggested that the treatment combination impacted tumor infiltration by immune cells.

Figure 4. Correlative studies on pre- and post-biopsy tissues.

A) Example image of standard immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis for phosphorylated FAK1 (tyrosine 395) from paired patient samples taken pre- and post-treatment. B) Example image of multiplex IHC (left) and quantitation of pFAK high CK19+ cells in partied biopsies C) Patient biopsies were assessed by using flow cytometry (left) or IHC analysis (right) for the presence of different leukocyte subsets. These leukocytes for flow cytometry included the following T cell subsets: total CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTLs), Ki67+CD8+ CTLs, CD4+ T effector cells, FOXP3+ regulatory T cells, and CD3/CD19−CD11b+CD14+CD68+ tumor-associated macrophages. For IHC analysis, total CD8+ T cells in the biopsy and CD8+ T cells present within 100 μm of CK19+ cells were analyzed by HALO software. All data are displayed as log2fold changes between pre- and post-biopsies. D) Example IHC analyses for CD8 (brown) and CK19 (red) images for a pair of pre- and post-biopsies from a single patient. *denotes p<0.05 by paired parametric test (B) or Wilcoxon signed-rank test or one-sample test (C) as appropriate.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study evaluating a FAK inhibitor in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor and chemotherapy. Overall, the toxicities of defactinib and pembrolizumab with or without gemcitabine were very modest, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) being grade 1 or 2. Grade 3 AEs such as neutropenia and anemia were consistent with known side effects of gemcitabine. We did not observe significant immune-related toxicities.

The preliminary efficacy from this small study was overall encouraging, with room for improvement. For PDAC patients who have progressed on frontline FOLFIRINOX, G/A or gemcitabine monotherapy are available options. In this setting, a retrospective study showed that gemcitabine monotherapy achieved a DCR of 35% (with 11% ORR) and median PFS of 2.5 months(15). Another retrospective study similarly showed that gemcitabine monotherapy achieved a DCR of 40%, median PFS and OS of 2.1 and 3.7 months, respectively(16). Our refractory cohort treated with the defactinib and pembrolizumab with or without gemcitabine achieved a DCR of 80%, median PFS and OS of 3.6 and 7.8 months. These results were superior to gemcitabine alone and potentially comparable to gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in 2nd line setting, which reported a DCR of 58%, median PFS and OS of 5.1 and 8.8 months respectively(17). Again, the relatively tolerable triple regimen may be an option for patients who sustained significant neuropathy from frontline FOLFIRINOX and are not candidates for nab-paclitaxel.

In the maintenance cohort, PDAC patients who had SD after at least 4 months of 1st line G/A were enrolled. For treatment naïve patients, the phase III MPACT study showed that G/A achieved a DCR of 48% (23% ORR) and median PFS and OS of 5.5 and 8.5 months, respectively(2). Patients who were treated till PD had a median OS of 9.8 months and among these >50% received subsequent therapy(18). In our study, after initial SD with at least 4 months of G/A, the triple drug regimen delivered a DCR of 63.6%, median PFS and OS of 5.0 months and 8.3 months. Median PFS and OS from initiation of G/A were 11.3 and 20.6 months, respectively, as compared to 5.5 and 8.5 months in the MPACT study. It is worth also mentioning that three patients in the maintenance cohort dropped out without radiographic progression and passed away shortly, which could impact our survival analyses in this small study. In addition, it is entirely possible that patients who had SD after 4 months of G/A may have more favorable tumor biology. However, the triple drug regimen could potentially be more tolerable as it is not neurotoxic and less myelosuppressive then continuation of G/A. This advantage may increase the likelihood of patients being treated and tolerate subsequent treatment regimens such as mFOLFIRINOX or 5-FU/liposomal-irinotecan, which is critical in prolonging their survival. From an immunological aspect, the defactinib/pembrolizumab/gemcitabine combination revealed the enhanced recruitment of CD8+ T cells with reduced TAM and Treg cells. However, the changes in the tumor microenvironment did not directly correlate with treatment response, which may be related to the small sample size and tumor heterogeneity. Notably, collection of post-treatment biopsies in two PR patients was not possible due to a decrease in the previously easily accessible metastatic lesions.

A remarkable observation from our study is prolonged SD of > 4 months in a considerable number of patients (10 out of 20 in refractory cohort, 6 out of 10 patients in maintenance cohort, Figure 2A). Given the well-tolerated safety profile of the triple regimen, it is reasonable to speculate that addition of nab-paclitaxel may achieve better efficacy, which can be tested in frontline setting for treatment naïve patients. Furthermore, targeting FAK was shown to synergize with radiation in preclinical PDAC models(19), and is now being evaluation in a clinical trial (NTC04331041). While not evaluated here, preclinical studies have suggested that the relative contribution of SMAD vs. signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling may control responsiveness to FAK inhibition in PDAC mouse models (20). This may also suggest differences in tumor subtypes, such as classical and basal or underlying genomic biology (e.g., SMAD mutations), which might influence the effects of FAK inhibition. Further, patient selection criterion might benefit from selection of pFAK high patients of patients with loss of Merlin deficiency(21). But these remain to be explored.

In short, our study showed that defactinib in combination with gemcitabine and pembrolizumab is safe, well-tolerated and showed encouraging preliminary benefit, further testing with more potent chemotherapy backbone such as G/A in a randomized controlled trial may be considered in the future.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Checkpoint immunotherapy is now an integral treatment option for many cancer types. However, the efficacy of this modality is limited in PDAC due to the various biological obstacles particularly the immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment that consists of a dense stroma and heavy infiltration of suppressive myeloid cells. Preclinical PDAC model showed that targeting focal adhesion kinase (FAK) could overcome these obstacles and induce responsiveness to anti-PD-1, especially when combined with chemotherapy. On this premise, we conducted a phase 1 clinical study combining a FAK inhibitor (defactinib), anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab), and gemcitabine in PDAC patients. Our results showed that this approach was safe, well-tolerated and resulted in promising anti-tumor activity in PDAC patients in both refractory and maintenance settings. Analysis of tumor biopsies showed reduced suppressive macrophages and increased infiltration of cytotoxic T cells. A randomized controlled clinical trial that includes more potent chemotherapy backbone and biomarker studies may be considered.

Acknowledgements

D.G.D. and A.W.G. were supported by NCI R01CA177670, R01CA203890, P30CA09184215, and the BJC Cancer Frontier Fund. The trial was also supported by Verastem and Merck for the therapeutic agents, defactinib and pembrolizumab, respectively.

Funding:

NCI R01CA203890, Barnes Jewish Foundation, Precision Medicine Research Associates, Verastem, Merck.

Role of the funding source

Commercial, private foundation, or federal funding sources had no role in the study execution, data collection, analysis, nor manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364(19):1817–25 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013;369(18):1691–703 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017;357(6349):409–13 doi 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Reilly EM, Oh DY, Dhani N, Renouf DJ, Lee MA, Sun W, et al. Durvalumab With or Without Tremelimumab for Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5(10):1431–8 doi 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu ZI, Shia J, Stadler ZK, Varghese AM, Capanu M, Salo-Mullen E, et al. Evaluating Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Challenges and Recommendations. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2018;24(6):1326–36 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammel P, Zhang C, Matile J, Colle E, Hadj-Naceur I, Gagaille MP, et al. PARP inhibition in treatment of pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2020;20(11):939–45 doi 10.1080/14737140.2020.1820330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong W, Raufi AG, Safyan RA, Bates SE, Manji GA. BRCA Mutations in Pancreas Cancer: Spectrum, Current Management, Challenges and Future Prospects. Cancer Manag Res 2020;12:2731–42 doi 10.2147/CMAR.S211151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serrels A, Lund T, Serrels B, Byron A, McPherson RC, von Kriegsheim A, et al. Nuclear FAK controls chemokine transcription, Tregs, and evasion of anti-tumor immunity. Cell 2015;163(1):160–73 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frame MC, Patel H, Serrels B, Lietha D, Eck MJ. The FERM domain: organizing the structure and function of FAK. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010;11(11):802–14 doi 10.1038/nrm2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang H, Hegde S, Knolhoff BL, Zhu Y, Herndon JM, Meyer MA, et al. Targeting focal adhesion kinase renders pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat Med 2016;22(8):851–60 doi 10.1038/nm.4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stokes JB, Adair SJ, Slack-Davis JK, Walters DM, Tilghman RW, Hershey ED, et al. Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase by PF-562,271 inhibits the growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer concomitant with altering the tumor microenvironment. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2011;10(11):2135–45 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Infante JR, Camidge DR, Mileshkin LR, Chen EX, Hicks RJ, Rischin D, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic phase I dose-escalation trial of PF-00562271, an inhibitor of focal adhesion kinase, in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(13):1527–33 doi 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones SF, Siu LL, Bendell JC, Cleary JM, Razak AR, Infante JR, et al. A phase I study of VS-6063, a second-generation focal adhesion kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 2015;33(5):1100–7 doi 10.1007/s10637-015-0282-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu T, Fukuoka K, Takeda M, Iwasa T, Yoshida T, Horobin J, et al. A first-in-Asian phase 1 study to evaluate safety, pharmacokinetics and clinical activity of VS-6063, a focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inhibitor in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2016;77(5):997–1003 doi 10.1007/s00280-016-3010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilabert M, Chanez B, Rho YS, Giovanini M, Turrini O, Batist G, et al. Evaluation of gemcitabine efficacy after the FOLFIRINOX regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(16):e6544 doi 10.1097/MD.0000000000006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viaud J, Brac C, Artru P, Le Pabic E, Leconte B, Bodere A, et al. Gemcitabine as second-line chemotherapy after Folfirinox failure in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49(6):692–6 doi 10.1016/j.dld.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Portal A, Pernot S, Tougeron D, Arbaud C, Bidault AT, de la Fouchardiere C, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma after Folfirinox failure: an AGEO prospective multicentre cohort. Br J Cancer 2015;113(7):989–95 doi 10.1038/bjc.2015.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel A, Rommler-Zehrer J, Li JS, McGovern D, Romano A, Stahl M. Efficacy and safety profile of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer treated to disease progression: a subanalysis from a phase 3 trial (MPACT). BMC Cancer 2016;16(1):817 doi 10.1186/s12885-016-2798-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang KJ, Constanzo JD, Venkateswaran N, Melegari M, Ilcheva M, Morales JC, et al. Focal Adhesion Kinase Regulates the DNA Damage Response and Its Inhibition Radiosensitizes Mutant KRAS Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22(23):5851–63 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, Liu X, Knolhoff BL, Hegde S, Lee KB, Jiang H, et al. Development of resistance to FAK inhibition in pancreatic cancer is linked to stromal depletion. Gut 2020;69(1):122–32 doi 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro IM, Kolev VN, Vidal CM, Kadariya Y, Ring JE, Wright Q, et al. Merlin deficiency predicts FAK inhibitor sensitivity: a synthetic lethal relationship. Sci Transl Med 2014;6(237):237ra68 doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.