Abstract

Background & Aims

The contribution of abnormal metabolic targets to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) progression and the associated regulatory mechanisms are attractive research areas. High-density lipoprotein binding protein (HDLBP) is an important transporter that protects cells from excessive cholesterol accumulation, but few studies have identified a role for HDLBP in HCC progression.

Methods

HDLBP expression was determined in HCC tissues and published datasets. The biological roles of HDLBP in vitro and in vivo were examined by performing a series of functional experiments.

Results

An integrated analysis confirmed that HDLBP expression was significantly elevated in HCC compared with noncancerous liver tissues. The knockdown or overexpression of HDLBP substantially inhibited or enhanced, respectively, HCC proliferation and sorafenib resistance. Subsequently, a mass spectrometry screen identified RAF1 as a potential downstream target of HDLBP. Mechanistically, when RAF1 was stabilized by HDLBP, MEKK1 continuously induced RAF1Ser259-dependent MAPK signaling. Meanwhile, HDLBP interacted with RAF1 by competing with the TRIM71 E3 ligase and inhibited RAF1 degradation through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that HDLBP is an important mediator that stabilizes the RAF1 protein and maintains its activity, leading to HCC progression and sorafenib resistance. Thus, HDLBP might represent a potential biomarker and future therapeutic target for HCC.

Keywords: MEKK1, Tripartite Motif Containing 71, Ubiquitination, Vigilin

Abbreviations used in this paper: CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; CHX, cycloheximide; CoIP, coimmunoprecipitation; Flag-CTL, flag-tagged control; Flag-HBP, flag-tagged HDLBP overexpression plasmid; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HBP sg, CRISPR–Cas9-mediated knockout of HDLBP; HBP sh, short hairpin RNA plasmid; HBP si, short interfering RNAs for HDLBP; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HDLBP, high-density lipoprotein binding protein; HDLBP-Res, shRNA-resistant HDLBP overexpression plasmid; ICGC, International Cancer Genome Consortium; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; Lv-CTL, nontarget control lentivirus; Lv-HBP, HDLBP overexpression lentivirus; mRECIST, Modified Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; NCL, noncancer liver; NEDD4L, NEDD4-like E3 ubiquitin protein ligase; qRT–PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; SR, sorafenib resistant; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TRIM71, tripartite motif containing 71; Ub, Ubiquitin

Graphical abstract

SUMMARY.

High-density lipoprotein binding protein (HDLBP) is an important mediator that stabilizes RAF1 protein and maintains its activity, leading to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) progression and sorafenib resistance. Thus, HDLBP could be a novel therapeutic target for inhibiting HCC progression and attenuating sorafenib resistance in HCC.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most aggressive malignancies worldwide, ranking as the second most lethal human cancer.1 In the past decade, although some progress has been achieved in the systemic treatment of HCC, the 3-year overall survival rate of patients with HCC remains miserably low.2,3 Metabolic abnormalities are one of the major biological features of malignancies and comprehensively affect the biological behaviors of tumors, such as tumor growth, proliferation, and metastasis.4,5 Many benign and malignant liver diseases, including HCC, are associated with metabolic abnormalities.6 Although the roles of many metabolic molecules or products in tumors have been investigated after years of dedicated studies,7 few metabolic factors have been identified as effective therapeutic targets for HCC. Therefore, we must further improve our understanding of the molecular mechanisms associated with metabolic targets to develop better treatment regimens for HCC.

Lipids are predominantly processed in the liver and play an important role in the pathological progression of HCC.8 Recent studies revealed that low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 promotes the glioblastoma response to gefitinib through endocytosis.9 Specific inhibition of the plasma membrane receptors for excess high-density lipoprotein cholesterol shows great potential for the treatment of cancer.10 In addition, targeted inhibition of lipoprotein lipase significantly reduces the incidence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated HCC.11 These results undoubtedly highlight the potential importance of abnormalities in the lipoprotein family in promoting HCC progression and as a therapeutic target for HCC. In this study, we attempted to investigate the biological role of one member of the lipoprotein family: high-density lipoprotein-binding protein (HDLBP). HDLBP, also known as vigilin, is engaged in multiple biological processes and plays an essential role in protecting cells from excessive cholesterol accumulation.12,13 However, little is known about the role of HDLBP in carcinogenesis. A previous study suggested that elevated HDLBP expression promotes HCC progression.14 However, the underlying mechanisms by which HDLBP affects HCC progression have not been fully investigated.

In this study, HDLBP expression levels in HCC tissues and noncancer liver (NCL) tissues were compared by performing an integrated analysis. HDLBP was further modulated to observe its effect on the proliferation and sorafenib sensitivity of HCC cells both in vitro and in vivo. By conducting coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) experiments, we revealed that HDLBP interacts with RAF1 and consistently activates the MAPK signaling pathway through MEKK1-dependent RAF1Ser259 phosphorylation. We further determined that HDLBP stabilizes RAF1 protein expression by suppressing tripartite motif containing 71 (TRIM71)-dependent ubiquitination and degradation.

Results

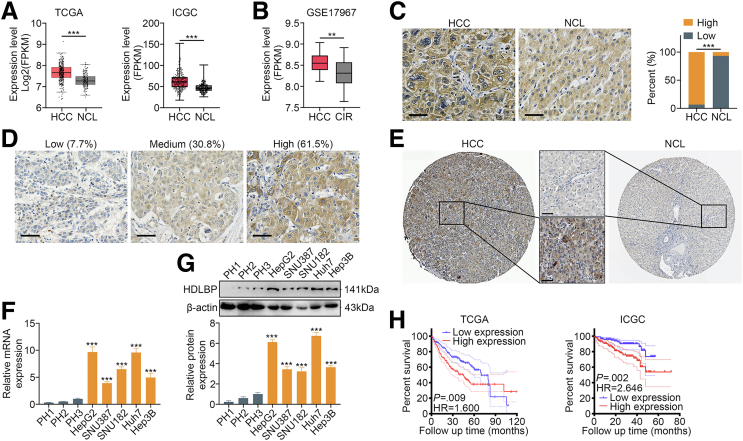

HDLBP Expression is Elevated in HCC Tissues and Correlates With a Poor Prognosis

We first analyzed HCC samples from liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) datasets, and the results suggested that HDLBP mRNA expression was markedly increased in HCC tissues compared with NCL tissues (Figure 1, A). Mining of the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset GSE17967 further suggested that HDLBP mRNA levels were markedly increased with HCC progression compared with cirrhosis (Figure 1, B). HDLBP protein expression was further analyzed by performing immunohistochemical (IHC) staining in our cohort of 30 HCC samples (patient cohort 1). Consistently, we found that HDLBP protein levels were significantly elevated in HCC tissues compared with paired NCL tissues (Figure 1, C). Moreover, an analysis of 26 patients with advanced HCC from cohort 1 showed that 92.3% of the samples expressed moderate to high levels of the HDLBP protein (Figure 1, D). Using the Human Protein Atlas,15 a similar elevation in the level of the HDLBP protein was confirmed in HCC compared with NCL tissues (Figure 1, E). Then, HDLBP expression was further detected in several HCC cell lines and primary human hepatocytes, and both quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and immunoblot results indicated that HDLBP was expressed at higher levels in HCC cell lines than in the primary human hepatocytes (Figure 1, F–G). Notably, Huh7 and HepG2 cells showed relatively high HDLBP expression, whereas Hep3B, SNU387, and SNU182 cells exhibited relatively low HDLBP expression (Figure 1, F–G).

Figure 1.

Elevated HDLBP expression is associated with the prognosis of patients with HCC.A, The FPKM levels of HDLBP from TCGA-LIHC and ICGC-LIHC datasets. FPKM, Fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments. B, The FPKM levels of HDLBP from GSE17967 datasets. CIR, cirrhosis. C, Representative images of IHC staining (left panel) of HCC samples with different HDLBP expression levels. Scale bars, 50 μm. Analysis of the relative expression (right panel) of HDLBP in HCC and NCL tissues. D, Representative images of IHC staining of HCC samples with different HDLBP levels. Scale bars, 50 μm. E, Representative images of IHC staining for HDLBP from the Human Protein Atlas. Scale bars, 50 μm. F, qRT-PCR analysis of HDLBP expression in primary hepatocytes (PHs) and 5 established HCC cell lines (Hep3B, Huh7, SNU182, SNU387, and HepG2). G, Immunoblots (upper panel) and relative quantitative analysis (lower panel) of HDLBP levels in PH and established HCC cell lines. H, Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to assess the correlation between HDLBP expression and overall survival (OS) of patients with HCC from TCGA-LIHC and ICGC-LIHC datasets. HDLBP expression was categorized as “high” or “low” using the median value as the cutoff point. For all the experiments described above, the data in A, B, F, and G are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and 3 independent experiments (N = 3) were performed in triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

Clinical data from patients with HCC were extracted from the TCGA-LIHC and ICGC-LIHC datasets to further investigate the correlation between HDLBP expression and the prognosis of patients with HCC. A Cox proportional hazards model indicated that the hazard ratio was significantly higher in patients with high HDLBP expression than in those with low HDLBP expression (Figure 1, H). These results imply that high HDLBP expression may be an adverse prognostic indicator for HCC.

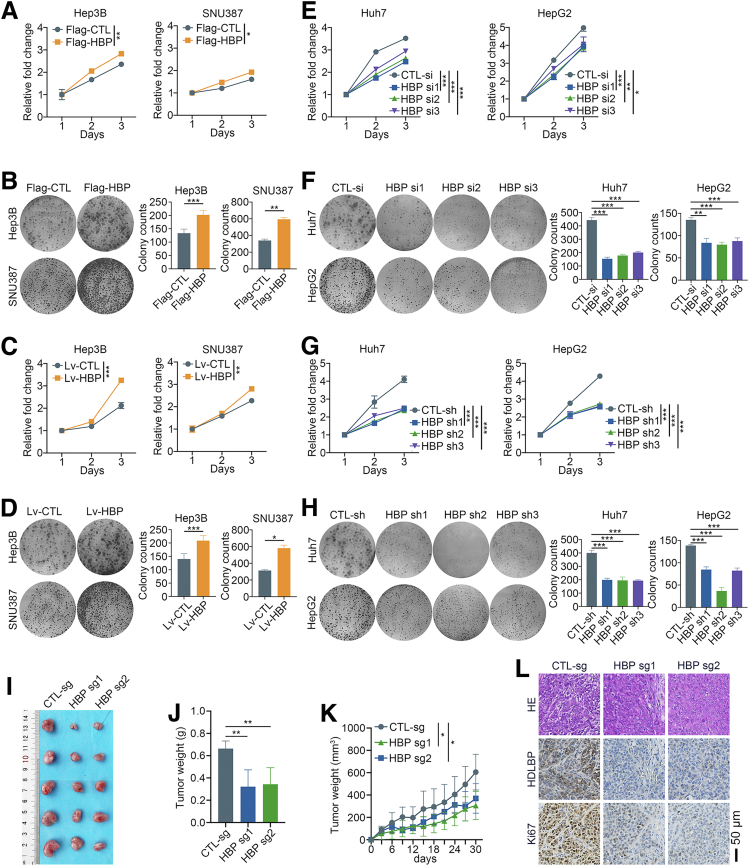

HDLBP Promotes HCC Proliferation and Progression In Vitro and In Vivo

A Flag-tagged control (Flag-CTL) and HDLBP overexpression plasmid (Flag-HBP) were transfected into Hep3B and SNU387 cells with low HDLBP expression to investigate the biological roles of HDLBP in HCC. HDLBP overexpression substantially increased the proliferation and colony formation of Hep3B and SNU387 cells (Figure 2, A–B). Then, Hep3B and SNU387 cells were subsequently infected with HDLBP overexpression lentivirus (Lv-HBP) and nontarget control lentivirus (Lv-CTL) to explore the roles of stable overexpression of HDLBP on HCC cell proliferation. As expected, the stable upregulation of HDLBP markedly increased the proliferation of HCC cells (Figure 2, C–D).

Figure 2.

HDLBP knockdown inhibits the proliferation of HCC cells in vitro and in vivo.A, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Hep3B and SNU387 cells transfected with the Flag tag vector control (Flag-CTL) or Flag tag plasmid containing the HDLBP sequence (Flag-HBP) at the indicated time points. B, A colony formation assay was performed in transfected cells for 2 weeks. Representative images (left panel) and the relative number of colonies (right panel) are shown. C, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Hep3B and SNU387 cells infected with the HDLBP overexpression lentivirus (Lv-HBP) or control lentivirus (Lv-CTL) at the indicated time points. D, A colony formation assay was performed in infected cells for 2 weeks. Representative images (left panel) and the relative number of colonies (right panel) are shown. E, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with the control siRNA (CTL-si) or HDLBP siRNAs (HBP-si) at the indicated time points. F, A colony formation assay was performed in transfected cells for 2 weeks. Representative images (left panel) and the relative number of colonies (right panel) are shown. G, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with the control shRNA (CTL-sh) or HDLBP shRNAs (HBP-sh) at the indicated time points. H, A colony formation assay was performed in transfected cells for 2 weeks. Representative images (left panel) and the relative number of colonies (right panel) are shown. I–K, Huh7 cells were stably infected with a lentivirus containing the CTL-sg or HBP-sg sequence. Transfected cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of male BALB/c nude mice (n = 5 mice per group). Representative images (I) of xenografts are displayed, and tumor weights (J) and volumes (K) were measured. L, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining and IHC staining for HDLBP and Ki67 expression in serial sections. For all the experiments described above, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and 3 independent experiments (N = 3) were performed in triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

Additionally, as a method to further investigate whether HDLBP knockdown aids in suppressing HCC progression, short interfering RNAs for HDLBP (HBP si) were applied to knockdown the expression of HDLBP in Huh7 and HepG2 cells with high HDLBP expression. HDLBP knockdown significantly suppressed HCC cell proliferation and colony formation (Figure 2, E–F). Moreover, silencing HDLBP by transfection with a short hairpin RNA plasmid (HBP sh) also markedly impaired the proliferation of HCC cells (Figure 2, G–H). Then, Huh7 cells infected with CRISPR–Cas9-mediated knockout construct for HDLBP (HBP sg) were subcutaneously inoculated into nude mice (Figure 2, I). Depletion of HDLBP in xenografts resulted in a significant reduction in both the tumor volume and weight (Figure 2, J–K). The IHC analysis also confirmed a remarkable decrease in the Ki67 expression, which was associated with HDLBP suppression (Figure 2, L). Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that HDLBP contributes to HCC proliferation and progression in vitro and in vivo.

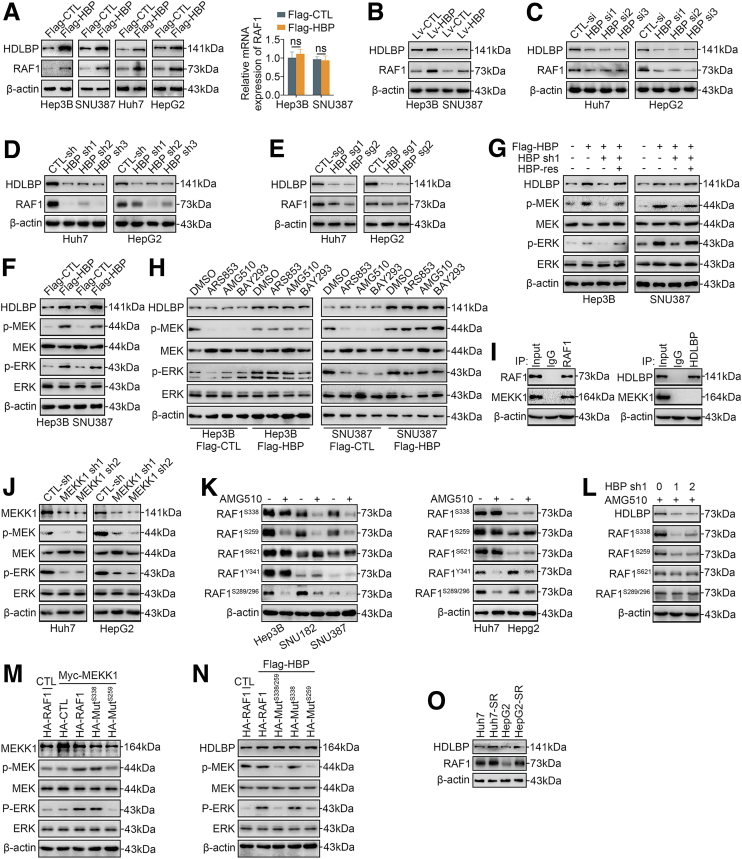

HDLBP Promotes the RAF1-MAPK Signaling Pathway in a MEKK1-dependent Manner

We performed a liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis to pull down proteins after a CoIP using antibodies against HDLBP as bait in the Huh7 cell lines to generate an HDLBP binding protein library and investigate the potential mechanism by which HDLBP promotes the progression of HCC (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, we found that RAF1, a key kinase in the MAPK signaling pathway, was in the binding protein library. Importantly, we confirmed that upregulation of HDLBP increased RAF1 protein levels but not mRNA levels (Figure 3, A–B). Then, we were curious whether the reduction in HDLBP expression would reverse the changes in RAF1 protein levels. Depletion of HDLBP by 3 independent genetic strategies (3 HDLBP siRNAs, 3 HDLBP shRNAs, and 2 HDLBP sgRNAs) significantly reduced RAF1 protein expression (Figure 3, C–E).

Figure 3.

HDLBP promotes the MEKK1-mediated RAF1-MAPK signaling pathway.A, Immunoblotting and qRT-PCR analyses of HDLBP and RAF1 expression in the indicated HCC cells transfected with Flag-CTL or Flag-HBP. B, Immunoblots showing HDLBP and RAF1 levels in Hep3B and SNU387 cells infected with Lv-HBP or Lv-CTL. C–E, Immunoblots showing HDLBP and RAF1 levels in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected or infected with the indicated sequence. F, Immunoblots showing HDLBP, p-ERK, ERK, p-MEK, and MEK levels in Hep3B and SNU387 cells transfected with Flag-CTL or Flag-HBP. G, Hep3B and SNU387 cells were transfected with Flag-HBP or the empty Flag vector for 12 hours and then cotransfected with HBP-sh, HBP-res, or the corresponding empty vector for 24 hours as indicated. The protein levels of HDLBP, p-ERK, ERK, p-MEK, and MEK were measured using immunoblotting. H, Hep3B and SNU387 cells were transfected with Flag-HBP or the empty Flag vector for 24 hours and then treated with the indicated Ras inhibitor for 12 hours. The protein levels of HDLBP, p-ERK, ERK, p-MEK, and MEK were measured using immunoblotting. I, Huh7 lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-IgG, anti-HDLBP, or anti-RAF1 antibody and immunoblotted with the indicated antibody. J, Immunoblot s showing the levels of MEKK1, p-ERK, ERK, p-MEK, and MEK in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with CTL-sh or MEKK1-sh. K, Immunoblots showing the levels of the indicated proteins in HCC cells treated with DMSO or AMG510 for 12 hours. L, Immunoblots showing the levels of the indicated proteins in Huh7 cells transfected with the indicated doses of HBP-sh1 for 12 h and then treated with AMG510 for 12 hours. M, Hep3B cells were transfected with Myc-MEKK1 or the empty Myc vector (CTL) for 12 hours and then transfected with HA-RAF1, HA-CTL, or HA fusion mutant vector for 24 hours. The levels of the indicated proteins were measured using immunoblotting. N, Hep3B cells were transfected with Flag-HBP or the empty Flag vector for 12 hours and transfected with HA-RAF or HA fusion mutant vector for 24 hours, and then transfected Huh7 cells were treated with AMG510 for 12 hours. The levels of the indicated proteins were measured using immunoblotting. O, Immunoblots showing the levels of HDLBP, and RAF1 in parental HCC cells and corresponding SR HCC cells. For all the experiments described above, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and 3 independent experiments (N = 3) were performed in triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, Not significant.

We next explored whether HDLBP affected the kinase activity of RAF1 in HCC. Interestingly, immunoblotting showed that HDLBP overexpression induced the phosphorylation of MEK and ERK in Hep3B and SNU387 cells (Figure 3, F), and this effect was inhibited by exogenous cotransfection of the HDLBP shRNA (Figure 3, G). However, the addition of an shRNA-resistant HDLBP overexpression plasmid (HDLBP-Res) to exogenous HDLBP-depleted Hep3B and SNU387 cells restored the levels of MEK and ERK phosphorylation (Figure 3, G), indicating that the HDLBP-RAF1 complex continuously facilitates downstream kinase activation. Notably, RAS is a classical stimulator of RAF1,16 and thus we used 3 different selective RAS inhibitors (ARS853, AMG510, and BAY293) to inhibit the phosphorylation of RAF1, but this inhibition was blocked by high HDLBP expression (Figure 3, H), suggesting that RAS is not an effector that continuously promotes the kinase activity of the HDLBP-RAF1 complex. MEKK1 has previously been reported as a key upstream kinase of RAF1,17 and our CoIP assays further confirmed the interaction of MEKK1 and RAF1 but not HDLBP (Figure 3, I). We next investigated whether MEKK1 stimulated the phosphorylation of RAF1. As expected, MEKK1 knockdown significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of MEK and ERK (Figure 3, J).

We further investigated RAF1 phosphorylation sites that were altered in response to MEKK1 kinase signaling. Interestingly, in the presence of AMG510, RAF1Ser338 and RAF1Ser259 phosphorylation was inhibited in Hep3B, SNU387, and SNU182 cells with low HDLBP expression. In contrast, phosphorylation at these sites was not inhibited in Huh7 and HepG2 cells with high HDLBP expression (Figure 3, K). In addition, HDLBP knockdown also abolished RAF1Ser338 and RAF1Ser259 phosphorylation in the presence of AMG510; as a control, the RAF1Ser621 and RAF1Ser289/Ser296 sites were not significantly regulated by HDLBP (Figure 3, L). Based on these results, the phosphorylation of RAF1Ser338 and RAF1Ser259 may be associated with elevated HDLBP expression but was not affected by RAS. Furthermore, consistent with the results for wild-type RAF1, the RAF1Ser338 mutant promoted the phosphorylation of MEK and ERK when MEKK1 was overexpressed. In contrast, MAPK downstream kinases were not phosphorylated following the introduction of the RAF1Ser259 mutant (Figure 3, M). In addition, wild-type RAF1 and RAF1Ser338 mutants that were expressed in HDLBP-overexpressing Hep3B cells were resistant to dephosphorylation induced by AMG510 (Figure 3, N). These results suggest that HDLBP promotes RAF1 expression and regulates the kinase activity of MEKK1 toward RAF1Ser259, thereby activating the RAF1-MAPK signaling pathway.

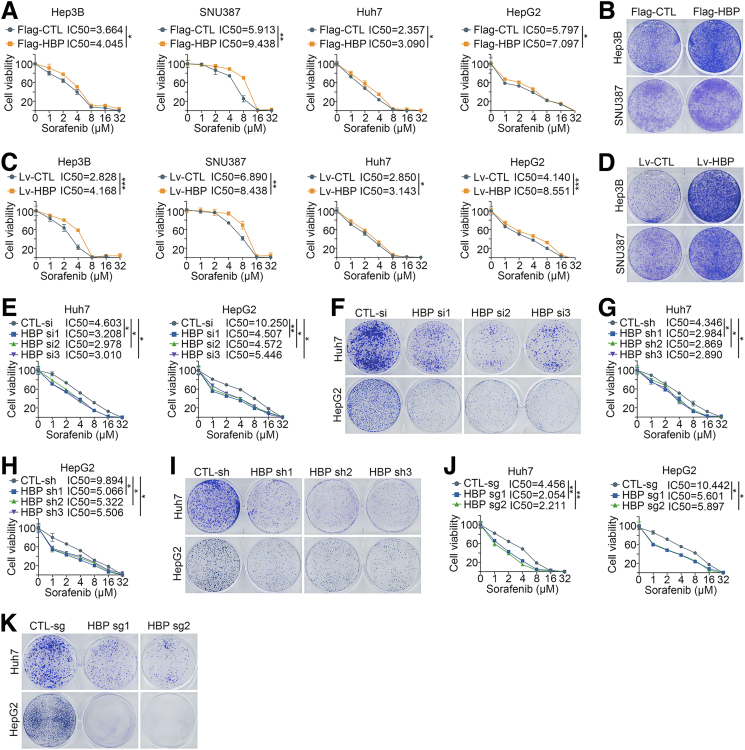

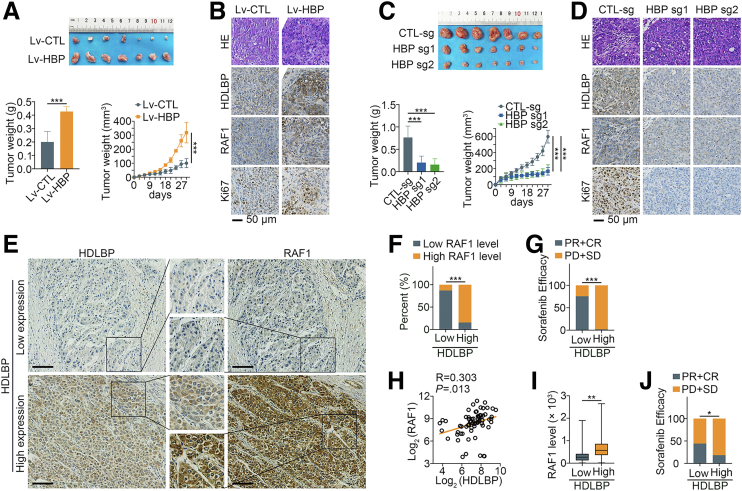

Elevated HDLBP Expression Confers HCC Sorafenib Resistance In Vitro and In Vivo

RAF1 is one of the major targets of sorafenib,18 and we wondered whether the activation of the RAF1-MAPK signaling pathway by HDLBP affects sorafenib sensitivity in HCC. As described in our previous publication,19 sorafenib-resistant HCC cell lines were cultured, and immunoblotting indicated that the expression levels of HDLBP and RAF1 were significantly increased in sorafenib-resistant Huh7 and HepG2 cells (Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells) (Figure 3, O). We further explored the effect of HDLBP expression on sorafenib sensitivity in HCC cells. Interestingly, HDLBP overexpression substantially increased the sorafenib resistance of HCC cells (Figure 4, A–D). On the other hand, depletion of HDLBP using distinct genetic strategies significantly reversed the sorafenib resistance of Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells compared with control parental HCC cells (Figure 4, E–K). We subcutaneously transplanted Hep3B cells infected with Lv-HBP or Lv-CTL into nude mice to futher validate whether HDLBP facilitated sorafenib resistance in HCC in vivo. After consecutive intraperitoneal injections of sorafenib every 3 days, the tumor growth and weight of the Lv-HBP group were obviously increased compared with those of the Lv-CTL group, suggesting that the subcutaneous tumors in the HDLBP overexpression group were more resistant to sorafenib (Figure 5, A). IHC staining further confirmed that xenograft tumors in the HDLBP overexpression group expressed higher levels of RAF1 and the proliferation marker Ki67 (Figure 5, B). Next, we subcutaneously injected nude mice with Huh7-SR cells infected with or without the CRISPR–Cas9-mediated knockout construct for HDLBP. Deletion of the HDLBP protein substantially inhibited tumor growth in sorafenib-treated nude mice (Figure 5, C), along with a corresponding reduction in RAF1 and Ki67 expression (Figure 5, D).

Figure 4.

Elevated HDLBP expression confers sorafenib resistance in HCC cells.A, A CCK-8 assay was performed in HCC cells transfected with Flag-CTL or Flag-HBP and treated with a range of concentrations of sorafenib. Cell viability was assessed 3 days after sorafenib treatment. B, Hep3B and SNU387 cells were transfected with Flag-CTL or Flag-HBP and treated with 10 μmol sorafenib for 24 hours, then a clonogenic cell survival assay was performed for 2 weeks. C, A CCK-8 assay was performed in HCC cells infected with Lv-CTL or Lv-HBP and treated with a range of concentrations of sorafenib. Cell viability was assessed 3 days after sorafenib treatment. D, Hep3B and SNU387 cells were infected with Lv-CTL or Lv-HBP and treated with 10 μmol sorafenib for 24 hours, then a clonogenic cell survival assay was performed for 2 weeks. E, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells transfected with CTL-si or HBP si and treated with a range of concentrations of sorafenib. Cell viability was assessed 3 days after sorafenib treatment. F, Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells were transfected with CTL-si or HBP si and treated with 10 μmol sorafenib for 24 hours, then a clonogenic cell survival assay was performed for 2 weeks. G–H, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells transfected with CTL-sh or HBP sh and treated with a range of concentrations of sorafenib. Cell viability was assessed 3 days after sorafenib treatment. I, Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells were transfected with CTL-sh or HBP sh and treated with 10 μmol sorafenib for 24 hours, then a clonogenic cell survival assay was performed for 2 weeks. J, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells infected with CTL-sg or HBP sg and treated with a range of concentrations of sorafenib. Cell viability was assessed 3 days after sorafenib treatment. K, Huh7-SR and HepG2-SR cells were infected with CTL-sg or HBP sg and treated with 10 μmol sorafenib for 24 hours, then a clonogenic cell survival assay was performed for 2 weeks. For all the above experiments, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and 3 independent experiments (N = 3) were performed in triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

Figure 5.

HDLBP causes sorafenib resistance in HCC in vivo.A, Hep3B cells infected with Lv-HBP or Lv-CTL were transplanted into the right flanks of mice (n = 7 mice per group), and the differences in tumor growth after sorafenib treatment are shown (upper panel). The xenografted tumors in the mice were weighed, and the growth of tumors was measured (lower panel). B, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining and IHC staining for HDLBP, RAF1, and Ki67 expression in serial sections. C, Huh7-SR cells infected with CTL-sg or HBP-sg were transplanted into the right flanks of mice (n = 7 mice per group), and the differences in tumor growth after sorafenib treatment are shown (upper panel). The xenografted tumors in the mice were weighed, and the growth of tumors was measured (upper panel). D, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining and IHC staining for HDLBP, RAF1, and Ki67 expression in serial sections. E, Representative images of IHC staining for HDLBP and RAF1 in HCC samples from patient cohort 2 with different HDLBP expression levels. Scale bars, 100 μm. F, HDLBP expression was correlated with RAF1 expression in HCC samples from patient cohort 2. G, HDLBP expression was correlated with different sorafenib efficacies in patients with HCC from patient cohort 2. In H and I, the expression levels of HDLBP and RAF1 were classified as low if the immunoreactivity score was less than 5 and high if the immunoreactivity score was ≥5. H, The Pearson correlation analysis between HDLBP and RAF1 expression in GSE109211. I, Box plot of RAF1 expression in HCC with different HDLBP expression levels. J, HDLBP expression was correlated with different sorafenib sensitivities in patients with HCC from GSE109211. For all the aforementioned experiments, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

We obtained clinical samples from the initial surgery of patients with early relapsed HCC (patient cohort 2) who were taking sorafenib to better evaluate the clinical correlation of HDLBP expression and sorafenib resistance in HCC. Interestingly, our results revealed that high HDLBP expression was associated with high RAF1 expression in these patients (Figure 5, E–F). More importantly, we observed a positive correlation between HDLBP expression and sorafenib resistance (Figure 5, G), which revealed that HDLBP expression potentially predicted the clinical outcome of sorafenib therapy. Additionally, high HDLBP expression was associated with an advanced Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, poor tumor differentiation, presence of microsatellite nodules, and larger tumor diameter (Table 1). We analyzed HDLBP expression in 67 samples from patients with HCC who taking sorafenib in the GEO database (GSE109211) to further confirm the clinical value of HDLBP. Indeed, the HDLBP level was positively correlated with the RAF1 expression in HCC (Figure 5, H–I). Moreover, excessive HDLBP positivity was an unfavorable predictor of sorafenib efficacy in patients with HCC (Figure 5, J). Taken together, these results suggest that elevated HDLBP expression confers sorafenib resistance in HCC in vitro and in vivo.

Table 1.

Correlation of HDLBP Expression With Clinicopathological Parameters From Patient Cohort 2 in This Study

| HDLBP | High (n = 57) | Low (n = 70) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCLC stage | A | 17 | 32 | < .018a |

| B | 20 | 28 | ||

| C | 20 | 10 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | No | 39 | 45 | .601 |

| Yes | 17 | 24 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | Poor | 55 | 27 | < .001a |

| Well | 1 | 28 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | No | 19 | 23 | 1.000 |

| Yes | 38 | 46 | ||

| Number of HCC | 1 | 41 | 59 | .087 |

| >1 | 15 | 10 | ||

| HBsAg | − | 11 | 17 | .500 |

| + | 46 | 53 | ||

| HBV DNA | − | 32 | 45 | .350 |

| + | 25 | 25 | ||

| Child-Pugh classification | A | 56 | 65 | .155 |

| B | 1 | 5 | ||

| Microsatellite nodules | No | 36 | 57 | .004a |

| Yes | 20 | 9 | ||

| Sorafenib efficacy | PD + SD | 56 | 17 | < .001a |

| PR + SR | 1 | 53 | ||

| Maximum tumor diameter, cm | 8.388 ± 3.292 | 4.839 ± 2.400 | .005a | |

| Total tumor diameter, cm | 6.653 ± 3.714 | 5.236 ± 2.420 | .022a | |

| HGB, g/L | 148.900 ± 14.483 | 145.800 ± 19.587 | .328 | |

| TBIL, μmol/L | 17.120 ± 7.274 | 17.170 ± 10.734 | .978 | |

| DBIL, μmol/L | 6.761 ± 4.014 | 5.996 ± 2.681 | .204 | |

| ALT, IU/L | 70.880 ± 118.273 | 78.790 ± 103.570 | .694 | |

| AST, IU/L | 75.910 ± 127.287 | 76.210 ± 114.382 | .989 | |

| ALB, g/L | 43.260 ± 5.450 | 42.510 ± 5.475 | .448 | |

| UREA, mmol/L | 4.895 ± 1.428 | 5.188 ± 1.440 | .258 | |

| CREA, μmol/L | 73.900 ± 12.654 | 75.240 ± 19.617 | .659 | |

| PT, s | 20.170 ± 1.915 | 20.300 ± 1.525 | .665 | |

| INR | 1.265 ± 1.451 | 1.060 ± 0.135 | .241 | |

| Meld score | 8.201 ± 3.862 | 7.834 ± 2.078 | .496 | |

Note: Data are presented as number or mean ± standard deviation.

ALB, Albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CR, complete remission; CREA, creatinine; DBIL, direct bilirubin; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HDLBP, high-density lipoprotein binding protein;; HGB, hemoglobin; High, High expression; INR, international normalized ratio; Low, Low expression; Meld, model end-stage liver disease; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial remission; PT, prothrombin time; SD, stable disease; TBIL, total bilirubin.

Indicates statistical significance.

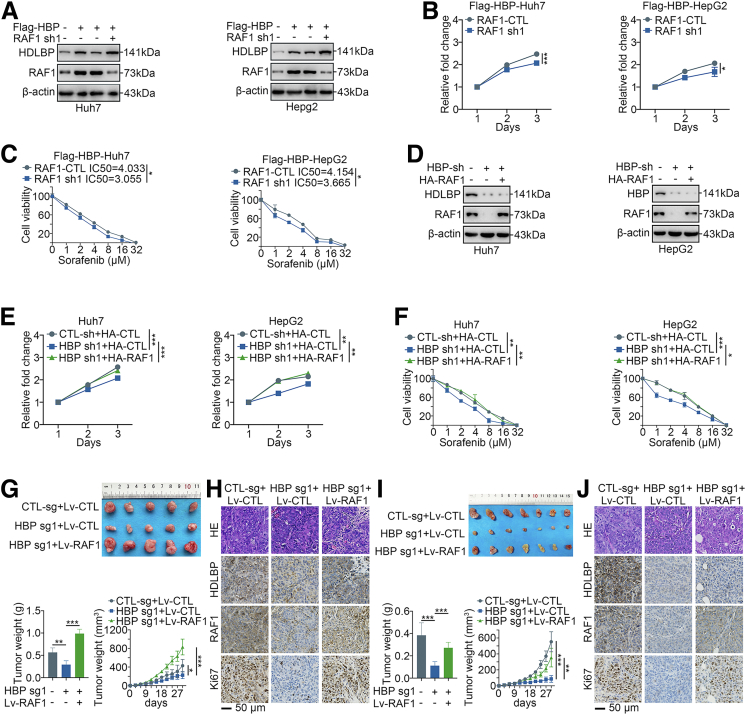

RAF1 is a Critical Target of HDLBP That Promotes HCC

We next confirmed the potential importance of RAF1 in HDLBP-mediated HCC progression and sorafenib resistance. Coincidently, cotransfection of the RAF1 shRNA dramatically abolished the HDLBP-mediated upregulation of RAF1 expression (Figure 6, A), as well as the proliferation and sorafenib resistance induced by HDLBP overexpression in Huh7 and HepG2 cells (Figure 6, B–C). Conversely, overexpression of RAF1 rescued the HDLBP sgRNA-induced inhibition of RAF1 expression (Figure 6, D), and the proliferation and sorafenib resistance of Huh7 and HepG2 cells were reversed by ectopic expression of RAF1 (Figure 6, E–F). Furthermore, consistent with the in vitro results, HDLBP knockout did not completely abolish xenograft growth, sorafenib resistance, or RAF1 and Ki67 expression when RAF1 was overexpressed (Figure 6, G–J), suggesting that RAF1 overexpression partially restored HDLBP knockout-induced suppression of HCC proliferation and resistance to sorafenib. Taken together, these results suggest that RAF1 is a critical target by which HDLBP exerts tumor-promoting effects on HCC.

Figure 6.

RAF1 is critical for the regulatory effect of HDLBP on proliferation and sorafenib resistance in HCC.A, Immunoblots showing the levels of HDLBP and RAF1 in Huh7 and HepG2 cells cotransfected with Flag-HBP, RAF1 sh1, and the corresponding empty vector for 24 hours as indicated. B, A CCK-8 assay was performed in transfected Huh7 and HepG2 cells at the indicated time points. C, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with the indicated vectors and treated with a range of concentrations of sorafenib. Cell viability was assessed 3 days after sorafenib treatment. D, Immunoblots showing the levels of HDLBP and RAF1 in Huh7 and HepG2 cells cotransfected with HBP sh, HA-RAF1 and the corresponding empty vector for 24 hours as indicated. E, A CCK-8 assay was performed in transfected Huh7 and HepG2 cells at the indicated time points. F, A CCK-8 assay was performed in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with the indicated vectors and treated with a range of concentrations of sorafenib. Cell viability was assessed 3 days after sorafenib treatment. G, Huh7 cells were stably infected with lentivirues containing HBP-sg1, Lv-RAF1, or the corresponding control sequence as indicated. Transfected cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of male BALB/c nude mice (n = 5 mice per group). Representative images of xenografts are displayed (upper panel), and tumor weights and volumes were measured (lower panel). H, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining and IHC staining for HDLBP, RAF1 and Ki67 expression in serial sections. I, Huh7 cells were stably infected with lentivirus containing HBP-sg1, Lv-RAF1, or the corresponding control sequence as indicated. Transfected cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of male BALB/c nude mice (n = 7 mice per group), and the differences in tumor growth after sorafenib treatment are shown (upper panel). The tumor weights and volumes were measured (lower panel). J, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin staining and IHC staining for HDLBP, RAF1, and Ki67 expression in serial sections. For all the experiments described above, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and 3 independent experiments (N = 3) were performed in triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

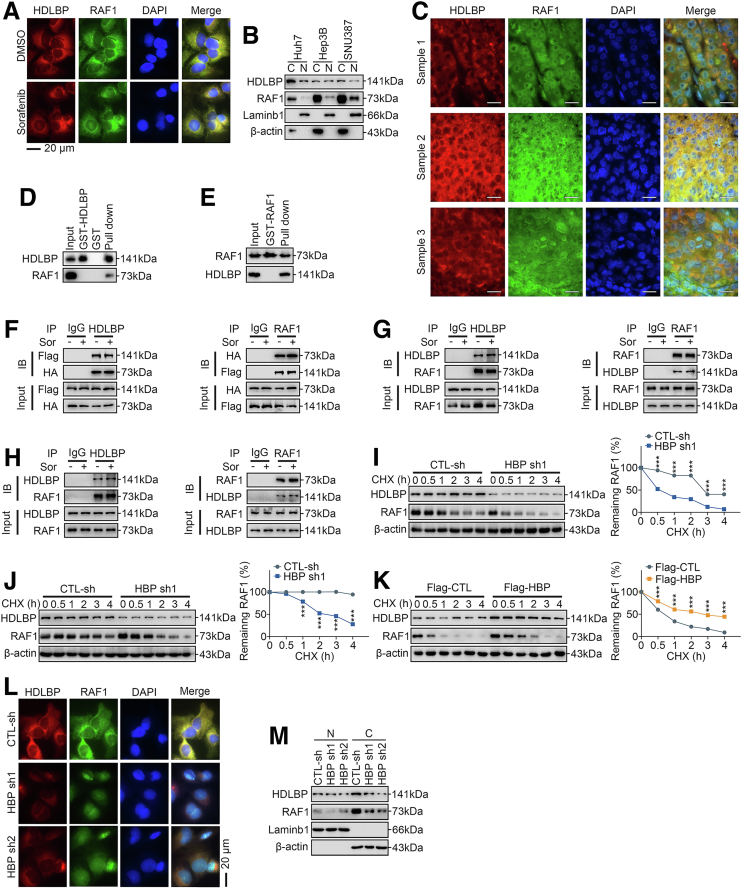

HDLBP Interacts With RAF1 and Inhibits Its Degradation

Our LC-MS/MS results implied that HDLBP potentially binds to RAF1 (Supplementary Table 1). We next investigated whether HDLBP and RAF1 colocalized in living HCC cells or HCC tissues using fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure 7, A, RAF1 and HDLBP mainly colocalized in the cytoplasm, regardless of the presence or absence of sorafenib, but both were expressed at a low level in the nucleus, which was further confirmed by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence staining of HCC tissues (Figure 7, B–C), suggesting that HDLBP might physically associate with RAF1. We conducted a glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay to determine whether HDLBP interacted with RAF1 in vitro. Figure 7, D shows that purified GST-fused HDLBP pulled down RAF1 from HEK293T cell lysates. Moreover, GST-RAF1 interacted with HDLBP (Figure 7, E). HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-RAF1 and Flag-HDLBP and cultured in the presence or absence of sorafenib to further characterize whether sorafenib affected the interaction of RAF1 with HDLBP. As indicated in Figure 7, F, Flag-HDLBP interacted with HA-RAF1 in a sorafenib-independent manner. HDLBP and RAF1 were immunoprecipitated with an anti-RAF1 or anti-HDLBP antibody from Huh7 and Hep3B HCC cells, which have endogenous HDLBP and RAF1 expression, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to immunoblot analysis to further ascertain the interaction of HDLBP with RAF1 in vivo. The data presented in Figure 7, G–H revealed that HDLBP and RAF1 were detected in the immunocomplexes in the presence or absence of sorafenib.

Figure 7.

HDLBP interacts with RAF1 and inhibits its degradation.A, The localization of either HDLBP or RAF1 in Huh7 cells in the presence or absence of 1 μmol sorafenib was analyzed using fluorescence microscopy. B, The localization of either HDLBP or RAF1 in HCC cells was analysed using immunoblotting. C, The localization of either HDLBP or RAF1 in clinical HCC samples was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. D–E, GST-HDLBP, GST-RAF1, or GST was incubated with total HEK293T cell lysates expressing HA-RAF1 or Flag-HBP for 2 hours and then detected using immunoblotting with anti-RAF1 or anti-HDLBP antibodies as indicated. F, HEK293T cell lysates expressing Flag-HDLBP or HA-RAF1 were incubated with an anti-HDLBP or anti-RAF1 antibody, and interacting proteins were detected with an anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody using immunoblotting as indicated. G, Huh7 and H, Hep3B cell lysates were incubated with an anti-RAF1 or anti-HDLBP antibody, and interacting proteins were detected with an anti-HDLBP or anti-RAF1 antibody using immunoblotting as indicated. I, Huh7 and J, HepG2 cells were transfected with CTL-sh or HBP-sh1 for 48 hours. CHX (10 μmol) was added for the indicated times, and the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for HDLBP and RAF1 levels (left panel). The relative quantification of RAF1 protein levels is shown (right panel). K, SNU387 cells were transfected with Flag-CTL or Flag-HBP for 48 hours. CHX (10 μmol) was added for the indicated times, and the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for HDLBP and RAF1 (left panel). The relative quantification of RAF1 protein levels is shown (right panel). Sor, Sorafenib. L, The localization of either HDLBP or RAF1 in Huh7 cells transfected with CTL-sh or HBP sh was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. M, Huh7 cells were transfected with CTL-sh or HBP sh1 for 24 hours. Then, HDLBP and RAF1 in the nucleus and cytoplasm were respectively detected by immunoblotting. C, Cytoplasm; N, nucleus. For all the experiments described above, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and 3 independent experiments (N = 3) were performed in triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

We next investigated the potential mechanisms by which endogenous HDLBP regulates RAF1 expression. As mentioned above, HDLBP overexpression did not result in a significant change in RAF1 mRNA levels (Figure 3, A); therefore, we speculated that HDLBP regulates RAF1 expression at the posttranscriptional level. In cycloheximide (CHX) chase assays, transfection of HDLBP shRNAs in Huh7 and HepG2 cells resulted in a clear reduction in the half-life of RAF1 compared with that in the control shRNA group (Figure 7, I–J), indicating that the decrease in HDLBP expression promoted the turnover of RAF1 protein. Conversely, transfection of Flag-HDLBP in SNU387 cells significantly inhibited the degradation of the endogenous RAF1 protein compared with the control vector group (Figure 7, K). Through immunofluorescence staining and immunoblotting, we further found that after the reduction in HDLBP expression, the RAF1 protein was significantly reduced in the cytoplasm but not in the nucleus (Figure 7, L–M). These observations reveal that HDLBP binds to and inhibits RAF1 protein degradation.

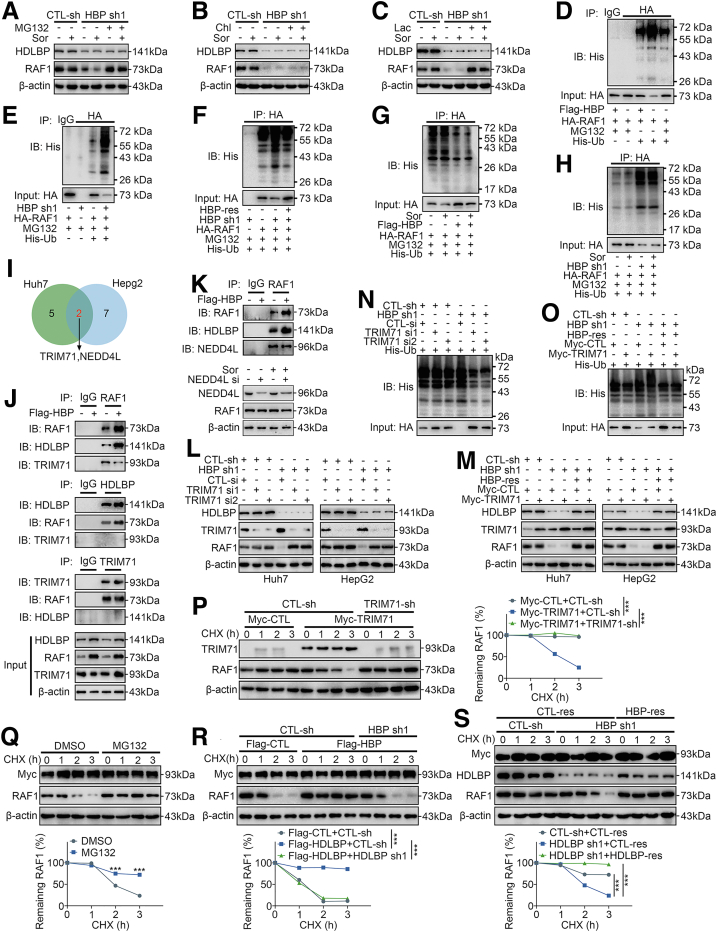

HDLBP Inhibits RAF1 Degradation Through the Ubiquitin–Proteasome Pathway

Huh7 cells transfected with HDLBP shRNAs were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 or the lysosome inhibitor chloroquine to further investigate the potential mechanisms by which HDLBP inhibits the degradation of RAF1 protein. Interestingly, the addition of MG132 effectively abrogated the effects of HDLBP silencing on RAF1 protein degradation (Figure 8, A), but the addition of chloroquine did not prevent the degradation of RAF1 protein (Figure 8, B). Consistently, the addition of the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin also blocked RAF1 protein degradation (Figure 8, C), indicating that HDLBP silencing promotes RAF1 degradation via the proteasome pathway. We next sought to determine whether the HDLBP-induced degradation of RAF1 was a consequence of RAF1 ubiquitination. Interestingly, ectopic expression of HDLBP substantially decreased the level of ubiquitylated RAF1, and MG132 also protected RAF1 from ubiquitylation (Figure 8, D). Conversely, HDLBP knockdown markedly accelerated RAF1 ubiquitylation, as revealed by Western blotting (Figure 8, E), and this acceleration was rescued by HDLBP-Res (Figure 8, F). In addition, we further confirmed that sorafenib failed to affect the regulation of RAF1 ubiquitylation induced by HDLBP overexpression or silencing (Figure 8, G–H). These data illustrate that HDLBP regulates RAF1 protein abundance through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway.

Figure 8.

HDLBP abrogates TRIM71-mediated RAF1 ubiquitination.A–C, Huh7 cells were transfected with CTL-sh or HBP sh1 for 24 hours. Then, the cells were treated with 1 μmol sorafenib and the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (30 mmol), chloroquine (Chl, 30 mmol), or lactacystin (Lac, 10 mmol) for 12 hours, and immunoblotting was performed with anti-RAF1 and anti-HDLBP antibodies. D, HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and treated with MG132 for 12 hours. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-IgG or anti-HA antibody and detected with an anti-His antibody. E, Huh7 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and treated with MG132 for 12 hours. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-IgG or anti-HA antibody and detected with an anti-His antibody. F, Huh7 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and treated with MG132 for 12 hours. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody and detected with an anti-His antibody. G–H, SNU387 (G) and Huh7 (H) cells were transfected and treated as indicated. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody and detected with an anti-His antibody. I, Schematic diagram of the screening process for E3 ligases mediating RAF1 degradation. J, Huh7 cells were transfected with Flag-CTL or Flag-HBP for 48 hours. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated primary antibody and immunoblotted as indicated. K, Huh7 cells were transfected with Flag-CTL or Flag-HBP for 48 hours. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-IgG or anti-RAF1 and immunoblotted as indicated (upper panel). Huh7 cells were transfected with NEDD4L si or CTL-si for 24 hours and were treated with 1 μmol of sorafenib (Sor) for 12 hours, and then immunoblot was performed with anti-NEDD4L and anti-RAF1 (lower panel). L–M, Immunoblots showing the levels of HDLBP, RAF1 and TRIM71 in Huh7 and HepG2 cells transfected with the indicated constructs. N–O, Huh7 cells were transfected as indicated, and then cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-RAF1 antibody and detected with anti-His antibody. P, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-RAF1 for 24 hours and then cotransfected with Myc-TRIM71, TRIM71-sh, or the corresponding empty vector for 24 hours as indicated. CHX was added for the indicated times, and the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for TRIM71 and RAF1 (left panel). The relative quantification of RAF1 protein levels is shown (right panel). Q, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HA-RAF1 and Myc-TRIM71 for 24 hours and then treated with DMSO or MG132 for 12 hours. CHX was added for the indicated times, and the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for RAF1 and Myc (left panel). The relative quantification of RAF1 protein levels is shown (right panel). R, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HA-RAF1 and Myc-TRIM71 for 12 hours and then transfected with Flag-HBP, HBP sh, or the corresponding empty vector for 24 hours as indicated. CHX was added for the indicated times, and the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for RAF1, Flag, and Myc (left panel). The relative quantification of RAF1 protein levels is shown (right panel). S, Huh7 cells were transfected with Myc-TRIM71 or Myc-CTL for 12 hours, and then were cotransfected with HBP sh, HBP-res, or the corresponding empty vector for 24 hours as indicated. CHX (10 μmol) was added for the indicated time, and the cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting of RAF1, HDLBP, and Myc (left). The relative quantification of RAF1 protein levels (right). For all the experiments shown above, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), and 3 independent experiments (N = 3) were performed in triplicate. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; and ∗∗∗P < .001.

HDLBP Abrogates the TRIM71-dependent Ubiquitination-mediated Degradation of RAF1

E3 ligases are key mediators of the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins.20 Because HDLBP does not contain domains identified as motifs for ubiquitin binding, we speculated that HDLBP regulates RAF1 ubiquitination by affecting the binding of RAF1 and E3 ligases. We performed an LC-MS/MS analysis after CoIP using an antibody against RAF1 in the Huh7 and HepG2 cell lines to identify the potential E3 ligases mediating the degradation of RAF1 (Supplementary Table 1). By analyzing the RAF1-binding protein library, TRIM71 and NEDD4-like E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (NEDD4L) were identified (Figure 8, I). The CoIP analysis further suggested that the binding of TRIM71 to RAF1 was significantly reduced when HDLBP was overexpressed, whereas HDLBP and TRIM71 failed to directly bind to each other (Figure 8, J). Moreover, the binding of NEDD4L to RAF1 was not significantly affected by the HDLBP protein abundance, and knockdown of NEDD4L failed to alter the RAF1 protein levels (Figure 8, K). We therefore suspected that HDLBP binds RAF1 competitively with TRIM71.

Interestingly, low TRIM71 expression in HDLBP-silenced Huh7 or HepG2 cells led to increased RAF1 protein levels (Figure 8, L). Conversely, increasing the endogenous amount of TRIM71 in Huh7 and HepG2 cells resulted in a marked decrease in RAF1 protein abundance (Figure 8, M). Moreover, when an shRNA-resistant HDLBP-encoding plasmid was expressed in Huh7 and HepG2 cells, HDLBP overexpression significantly increased the stability of RAF1, regardless of the expression level of TRIM71 (Figure 8, M). Indeed, TRIM71 knockdown substantially decreased the ubiquitylation level of the RAF1 protein (Figure 8, N). Conversely, HDLBP knockdown markedly increased RAF1 ubiquitylation, and this increase was rescued by HDLBP-Res regardless of the presence of TRIM71 (Figure 8, O).

We performed CHX chase assays to further validate that the ubiquitination mediated by TRIM71 promotes RAF1 degradation. The ectopic expression of TRIM71 promoted RAF1 degradation, whereas cotransfection with TRIM71 shRNAs suppressed RAF1 degradation (Figure 8, P). Moreover, the TRIM71-mediated degradation of RAF1 was considerably reduced in the presence of MG132 (Figure 8, Q). Furthermore, the TRIM71-mediated degradation of RAF1 was also significantly suppressed when HDLBP was exogenously overexpressed, but cotransfection of the HDLBP shRNA increased RAF1 degradation (Figure 8, R). Conversely, the reduction in endogenous HDLBP expression in Huh7 cells promoted RAF1 degradation, but HDLBP-Res significantly suppressed the degradation of RAF1 (Figure 8, S). Based on these data, TRIM71 is a pivotal E3 ubiquitin ligase that mediates RAF1 degradation, and the role of TRIM71 in ubiquitination is suppressed by increases in HDLBP protein levels.

Discussion

Elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of HCC progression and sorafenib resistance may provide individualized treatment options and new therapeutic targets for HCC, which remain the subject of extensive research.

Although HDLBP has complex functions in tumors, several mechanisms by which it regulates sterol metabolism and RNA binding have been identified.12,21 In contrast, investigations on its regulation of tumor progression and drug resistance are limited. Our study proposed that HDLBP expression was significantly increased in HCC tissues compared with NCL tissues. HDLBP knockdown significantly inhibited HCC progression and sorafenib resistance both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, HDLBP promoted the expression of RAF1 and regulated the kinase activity of MEKK1 toward RAF1Ser259-dependent MAPK signaling pathway to stimulate HCC progression and sorafenib resistance. These data provide additional insights into the potential mechanisms of HCC progression and sorafenib resistance, thus providing more evidence for individualized treatment of HCC.

The phosphorylation of RAF1 is one of the potential key mechanisms of tumor progression and drug resistance.22 Shu et al reported that RAF1 phosphorylation at Ser338 is a potential marker of resistance to estrogen receptor-targeted therapy.23 In addition, compound 5, an inhibitor of the protein phosphatase Cdc25, inhibits RAF1Ser259 phosphorylation, leading to the induction of RAF1 kinase activity and ERK hyperphosphorylation.24 Although sorafenib therapy is recommended for all patients with advanced HCC to reduce the tumor burden and create opportunities for radical resection or subsequent therapy,25,26 most RAF1-positive tumors do not respond to sorafenib therapy.27 Our study indicated that RAF1 is constitutively phosphorylated at Ser259 and is thus constitutively activated in HCC cells. We found that patients exhibiting these features were less likely to benefit from sorafenib treatment, despite their RAF1-positive status. Our findings help explain why some patients with RAF1-positive tumors respond poorly to sorafenib treatment.27 Interestingly, Dougherty et al reported that hyperphosphorylation of the Ser259 site inhibits the RAS/RAF1 interaction and desensitizes RAF1 to additional stimuli.28 Consistent with a previous study, our results indicated that HDLBP promotes RAF1Ser259 phosphorylation independent of RAS activities. Based on accumulating evidence, many kinases stimulate the phosphorylation of RAF1 to regulate the malignant behavior of tumors.29,30 Hissom first reported the binding and regulatory effects of MEKK1 on RAF1.17 Our results showed that MEKK1 significantly increased the level of RAF1 phosphorylated at Ser259 in HCC cells.

RAF1 protein expression is largely controlled by the regulation of ubiquitination, but the exact modulatory mechanism has rarely been reported. Sebastian et al provided evidence for a model in which a novel interaction between the E3 ligase BRAP and 2 closely related deubiquitinases, USP15 and USP4, regulates RAF1/MAPK signaling transduction.31 According to Eun et al, PSMC5 displaces the E3 ligase HUWE1 from the scaffold complex to attenuate the ubiquitination of RAF1.32 As shown in the present study, HDLBP inhibited the ubiquitination and degradation of RAF1, and we further validated the potential binding of TRIM71 to RAF1 using CoIP assays and immunoblotting. Moreover, HDLBP stabilized the expression of RAF1 by competitively inhibiting TRIM71-mediated degradation of RAF1, which provides a new insight into the mechanism regulating the RAF1 protein in tumor cells. Interestingly, our in vivo and in vitro results implied that RAF1 levels were significantly reduced in HCC cells with low HDLBP expression, and sorafenib treatment was more effective in patients with these features than in patients with high HDLBP expression. By performing further explorations, we found that sorafenib might induce ferroptosis of HCC cells in these patients (data not shown), which explains the increased sensitivity of HCC to sorafenib upon reduced RAF1 levels.

Overall, we reported that RAF1 stabilization and phosphorylation at RAF1Ser259 is a key mechanism of HCC growth and sorafenib resistance that is exclusively regulated by HDLBP. Furthermore, our findings support HDLBP as a novel therapeutic target for inhibiting HCC progression and attenuating sorafenib resistance.

Methods

Clinical Samples

A retrospective analysis of resected HCC samples at West China Hospital of Sichuan University from May 2014 to December 2020 was performed. Two cohorts were included in this study. For HCC patient cohort 1, 30 fresh human HCC and paired NCL tissues were collected. For patient cohort 2, 127 HCC samples obtained from the initial surgery were included in accordance with the following criteria: (1) patients with early relapse (within 6 months); (2) a history of taking sorafenib; (3) prognostic information after taking sorafenib was available; and (4) all samples were confirmed to have a clinicopathological diagnosis of HCC through pathology reports. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded HCC tumor specimens were obtained from a tissue bank maintained in the West China Hospital. Importantly, the Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) were used to evaluate the drug responsiveness of patients after taking sorafenib. Based on the mRECIST criteria, HCC samples from patients who experienced partial remission or complete remission were considered sorafenib-sensitive samples, whereas HCC samples from patients with progressive disease or stable disease were considered SR samples. Detailed information about the patients is shown in Table 1 The study using clinical samples was approved by the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their relatives.

Cell Culture

Huh7, Hep3B, HepG2, and HEK293T cell lines were purchased from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China) and were cultured in complete medium containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (HyClone, Logan, UT). SNU387 and SNU182 cells were also purchased from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China) and were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone). All cells were cultured in the indicated medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 1000 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (HyClone) and were grown in a humidified air atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. All cell lines were analyzed by STR profiling for cell line authentication and routine mycoplasma detection. SR HCC cell lines from Huh7 and HepG2 parental cells were cultured for 8 months as previously described.19

Additionally, 3 cases of fresh liver tissues were obtained from explant specimens upon liver transplantation of diverse patients. Primary human hepatocytes were isolated from the respective liver tissues using collagenase/hyaluronidase digestion (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC) according to previously reported methods.33 This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University (2020, No 385). Informed consent forms were signed by all involved donors or their families and recipients.

DNA Construction and Mutagenesis

PCR-amplified human wild-type HDLBP, RAF1, MEKK1, and TRIM71 sequences were cloned into GV141-Flag, -HA, or -Myc vectors. Ubiquitin (Ub) was cloned into GV141-His vectors. The site-specific mutants in our study were generated according to the manufacturer’s (Genechem, Shanghai, China) instructions.

Transfection

Transfection was performed as previously described.19,34 The siRNAs were constructed by Tsingke (Tianjin, China). The following siRNAs were used in this study: HDLBP siRNA-1 sense 5'-GGUGAUAAGUUAAAGCAAAGA-3', HDLBP siRNA-1 anti-sense 5'-UUUGCUUUAACUUAUCACCUG-3'; HDLBP siRNA-2 sense 5'-GGUUAUUAGCACAAAGUUAGC-3', HDLBP siRNA-2 anti-sense 5'-UAACUUUGUGCUAAUAACCGU-3'; HDLBP siRNA-3 sense 5'-CAGUGUUGUUGAAGUCUUAAG-3', HDLBP siRNA-3 anti-sense 5'-UAAGACUUCAACAACACUGGA-3'; TRIM71 siRNA-1 sense 5'-GGUAGAUACUUAUGCUAUACU-3', TRIM71 siRNA-1 anti-sense 5'-UAUAGCAUAAGUAUCUACCUA-3'; TRIM71 siRNA-2 sense 5'-GAGUGUUGAUGUCAUAGUAUU-3', TRIM71 siRNA-2 anti-sense 5'-UACUAUGACAUCAACACUCUG-3'; NEDD4L siRNA sense 5'-CGAAGAUGUCACCAGUAUAAU-3', NEDD4L siRNA anti-sense 5'-UAUACUGGUGACAUCUUCGUG-3'.

Lentivirus Construction and Infection

The human HDLBP gene was inserted between the BamHI and AgeI sites of the GV208 vector to create the HDLBP overexpression lentivirus. A lentivirus with the empty GV208 vector was constructed as a control. sgRNAs targeting the HDLBP gene and Cas9 vectors were cloned into GV371-U6-HDLBP sgRNA-SV40-EGFP and GV371-CMV-Cas9-SV40-Puro, respectively. The HDLBP sgRNA sequences were sg1: GAACACCATCGCTTTGTTAT and sg2: GAACAAGATCCGACCCATCA. These recombinant lentiviruses were stably transfected into HCC cell lines according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were then cultured in this medium for 48 hours and subjected to additional assays. All the reagents used for the experiments described in this section were purchased from GeneChem (Shanghai, China).

Cell Counting Kit-8

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) proliferation assay was performed as previously described.35 Additionally, to examine the 50% inhibitory concentration of sorafenib in the indicated cells, the processed cells (1 × 103 cells per well) were inoculated in 96-well plates for 24 hours. Sorafenib was then administered at the indicated concentration and incubated for 72 hours. Then, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution were added to the wells and incubated for 4 hours. Finally, the absorbance at 450 nmol was recorded, and the results were analyzed.

Colony Formation Assay and Clonogenic Cell Survival Assay

A colony formation assay for evaluating proliferation was performed as previously described.34 For the sorafenib evaluation, the indicated cells were treated with sorafenib (10 μmol) for 24 hours, and then 3000 cells were plated into 6-well plates. Two weeks later, the colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by 30 minutes of incubation with 0.1% crystal violet. The 6-well plates were washed, and then colonies were visualized.

Coimmunoprecipitation

The CoIP assay was performed using CoIP kits (Abs955, Absin, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Briefly, the indicated cells were homogenized in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5% NP-40, 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM cocktail, 1 mM phosphoSTOP, 1 mM NEM, and 1 mM NAM). Five hundred micrograms of extracts were incubated with the indicated primary antibody or IgG as a negative control for 4 hours and Protein A/G-Sepharose beads for 2 hours at 4 °C. After extensive washes with phosphate buffered saline, the immunoprecipitates were used in the subsequent assays. Anti-HDLBP (Proteintech, 15406-1-AP, Wuhan, China, 1:100), Anti-RAF1 (Cell Signaling Technology, #53745, MA, USA, 1:50) and Anti-IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, #3900, MA, USA, 1:500) were used.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

For the identification of interacting proteins, the immunoprecipitates of the indicated cells were separated on SDS-PAGE gels, and protein bands were digested using 10 ng/μL sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega); the proteins were eluted using 0.1% formic acid and 75% acetonitrile. The eluted proteins were then subjected to quality control and qualitatively analyzed using a Q Exactive TM HF-X mass spectrometer from Novogene Co, Ltd. (Tianjin, China) to obtain the raw proteome data. The raw protein file was directly imported into the Proteome Discoverer 2.2 software for a database search, peptide spectrum matches, and protein quantification.

GST Pull-Down Assay

All GST fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta cells and purified. The HEK293T extracts expressing the indicated proteins were mixed with 5 μg of GST derivatives bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads in 0.5 mL of modified binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM cocktail, 1 mM phosphoSTOP, 1 mM NEM, and 1 mM NAM). The binding reaction was performed at 4 °C overnight, and the beads were subsequently washed 4 times with binding buffer and then subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described.19,34 The β-actin antibody was used to normalize protein expression. For CHX chase assays, cells were treated with 10 μmol CHX for 24 hours after transfection and collected at the indicated time points, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. Anti-HDLBP (Proteintech, 15406-1-AP, Wuhan, China, 1:800), Anti-RAF1 (Cell Signaling Technology, #53745, Danvers, MA, 1:800), Anti-β-actin (Proteintech, 66009-1-Ig, 1:2500), Anti-Lamin B1 (Proteintech, 12987-1-AP, 1:2500), Anti-Flag (Proteintech, 20543-1-AP, 1:2000), Anti-HA (Proteintech, 51064-2-AP, 1:3000), Anti-His (Proteintech, 66005-1-Ig, 1:2500), Anti-Myc (Proteintech, 16286-1-AP, 1:800), Anti-TRIM71 (Proteintech, 55003-1-AP, 1:800), Anti-NEDD4L (Proteintech, 13690-1-AP, 1:800), Anti-p-MEK (Cell Signaling Technology, #8727, 1:500), Anti-MEK (Cell Signaling Technology, #9154, 1:500), Anti-p-ERK (Cell Signaling Technology, #4695, 1:500), Anti-ERK (Cell Signaling Technology, #4377, 1:500), Anti-MEKK1 (Proteintech, 19970-1-AP, 1:500), Anti-RAF1S338 (Cell Signaling Technology, #9427, 1:500), Anti-RAF1S259 (Cell Signaling Technology, #9421, 1:500), Anti-RAF1S621 (Abcam, ab157201, Cambridge, UK, 1:500), Anti-RAF1Y341 (Abcam, ab59223, 1:500), and Anti-RAF1S289/296 (Cell Signaling Technology, #9431, 1:500) were used.

Quantitative Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

qRT-PCR was performed as previously described.19,34 The following primers were used in this study: RAF1 forward: 5'-GTCACAGCGAATCAGCCTCACCTTCA-3', RAF1 reverse: 5'-GACCCAATCCGAGTGGACAGCATCA-3'; β-actin forward: 5'-GAAGATCAAGATCATTGCTCC-3', β-actin reverse: 5'-TACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCA-3'.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described.19 Anti-HDLBP (Proteintech, 15406-1-AP, 1:100) and Anti-RAF1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7267, Dallas, Tx, 1:50) were used.

Mouse Studies

Six-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Byrness Weil Biotech Ltd (Chendu, China) and were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment on a controlled 12 hour light/dark cycle at a constant temperature and humidity, with food and water available ad libitum. Three million of the indicated cells were collected and subcutaneously injected into the mice. At least 5 mice per group were used in each experiment. Tumor growth was monitored weekly by measurements with callipers. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula: volume = 1/2 × longest diameter × (shortest diameter)2. For sorafenib treatment, 9 days after the subcutaneous cell injection, the mice were intraperitoneally injected with sorafenib every 3 days. Mice were euthanized at the indicated times. All operations on experimental animals were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All operations were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Histology and IHC were performed as previously described.19,34 Anti-HDLBP (Proteintech, 15406-1-AP, 1:100), Anti-RAF1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7267, 1:100), and Anti-Ki67 (Proteintech, 27309-1-AP, 1:2000) were used. The IHC results from human tissues were evaluated by 2 independent observers based on the percentage of positively stained cells (scored from 0–3 points) and intensity of staining (scored from 0–3 points), and a final immunoreactivity score (range 0–9 points) was obtained by multiplying the 2 scores. HDLBP and RAF1 expression levels were classified as low if the score was less than 5 and high if the score was ≥5.

Reagents

Sorafenib (S7397), MG132 (S2619), CHX (S7418), ARS853 (S8156), AMG510 (S8830), and BAY293 (S8826) were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX). Lactacystin (HY-16594) and chloroquine (HY-17589A) were purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ).

Database Data Source and Preprocessing

The results of analyses of TCGA-LIHC datasets were downloaded from the online GEPIA database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html). The raw fragment per kilobase values and clinical information in ICGC-LIHC datasets were downloaded from the UCSC XENA database. The series matrix files of the Affymetrix and Illumina-generated microarray for GSE109211 and GSE17967 were directly downloaded from the GEO database. The data were preprocessed as previously described.36,37

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses reported in this study were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp), and figures were produced using GraphPad Prism 6.0 or R software. All statistical data are presented as the means ± standard deviations. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times independently with similar results. Depending on the experiment type, data were analysed using the unpaired Student t test, Pearson’s correlation analysis, or 1-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis, where appropriate. The statistical significance was evaluated based on P values, and P < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Jiayin Yang (Conceptualization: Lead; Funding acquisition: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Jingsheng Yuan (Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Visualization: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Tao Lv (Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Lead; Software: Lead; Validation: Lead)

Jian Yang (Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Equal; Validation: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Zhenru Wu (Methodology: Supporting; Validation: Supporting)

Lvnan Yan (Conceptualization: Supporting; Data curation: Lead; Supervision: Supporting)

Yujun Shi (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Methodology: Lead; Project administration: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Li Jiang (Conceptualization: Supporting; Software: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82070674), the Sichuan Province Science and Technology Department Project (no. 2019YFG0036), the 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (no. ZY2017308), and the 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2020HXFH010 to Y. S. and ZYJC1808).

Contributor Information

Jiayin Yang, Email: doctoryjy@scu.edu.cn.

Yujun Shi, Email: shiyujun@scu.edu.cn.

Li Jiang, Email: jl339@126.com.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J.D., Hainaut P., Gores G.J., Amadou A., Plymoth A., Roberts L.R. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akce M., El-Rayes B.F., Bekaii-Saab T.S. Frontline therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15 doi: 10.1177/17562848221086126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuzu O.F., Noory M.A., Robertson G.P. The role of cholesterol in cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2063–2070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroemer G., Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riscal R., Skuli N., Simon M.C. Even cancer cells watch their cholesterol. Mol Cell. 2019;76:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S.J., Choi Y.J., Kim H.I., Moon H.E., Paek S.H., Kim T.Y., Ko S.G. Platycodin D inhibits autophagy and increases glioblastoma cell death via LDLR upregulation. Mol Oncol. 2022;16:250–268. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marques P.E., Nyegaard S., Collins R.F., Troise F., Freeman S.A., Trimble W.S., Grinstein S. Multimerization and retention of the scavenger receptor SR-B1 in the plasma membrane. Dev Cell. 2019;50:283–295.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teratani T., Tomita K., Furuhashi H., Sugihara N., Higashiyama M., Nishikawa M., Irie R., Takajo T., Wada A., Horiuchi K., Inaba K., Hanawa Y., Shibuya N., Okada Y., Kurihara C., Nishii S., Mizoguchi A., Hozumi H., Watanabe C., Komoto S., Nagao S., Yamamoto J., Miura S., Hokari R., Kanai T. Lipoprotein lipase up-regulation in hepatic stellate cells exacerbates liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatol Commun. 2019;3:1098–1112. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng M.H., Jansen R.P. Vol. 8. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA; 2017. (A jack of all trades: the RNA-binding protein vigilin). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woo H.H., Lee S.C., Stoffer J.B., Rush D., Chambers S.K. Phenotype of vigilin expressing breast cancer cells binding to the 69 nt 3'UTR element in CSF-1R mRNA. Transl Oncol. 2019;12:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang W.L., Wei L., Huang W.Q., Li R., Shen W.Y., Liu J.Y., Xu J.M., Li B., Qin Y. Vigilin is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma and is required for HCC cell proliferation and tumor growth. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:2328–2334. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhlén M., Fagerberg L., Hallström B.M., Lindskog C., Oksvold P., Mardinoglu A., Sivertsson Å., Kampf C., Sjöstedt E., Asplund A., Olsson I., Edlund K., Lundberg E., Navani S., Szigyarto C.A., Odeberg J., Djureinovic D., Takanen J.O., Hober S., Alm T., Edqvist P.H., Berling H., Tegel H., Mulder J., Rockberg J., Nilsson P., Schwenk J.M., Hamsten M., von Feilitzen K., Forsberg M., Persson L., Johansson F., Zwahlen M., von Heijne G., Nielsen J., Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347 doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gollob J.A., Wilhelm S., Carter C., Kelley S.L. Role of Raf kinase in cancer: therapeutic potential of targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK signal transduction pathway. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:392–406. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karandikar M., Xu S., Cobb M.H. MEKK1 binds raf-1 and the ERK2 cascade components. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40120–40127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauthier A., Ho M. Role of sorafenib in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan J., Yin Z., Tan L., Zhu W., Tao K., Wang G., Shi W., Gao J. Interferon regulatory factor-1 reverses chemoresistance by downregulating the expression of P-glycoprotein in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;457:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanarek N., Ben-Neriah Y. Regulation of NF-κB by ubiquitination and degradation of the IκBs. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:77–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou J., Wang Q., Chen L.L., Carmichael G.G. On the mechanism of induction of heterochromatin by the RNA-binding protein vigilin. RNA. 2008;14:1773–1781. doi: 10.1261/rna.1036308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang T., Ren C., Qiao P., Han X., Wang L., Lv S., Sun Y., Liu Z., Du Y., Yu Z. PIM2-mediated phosphorylation of hexokinase 2 is critical for tumor growth and paclitaxel resistance in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2018;37:5997–6009. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0386-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shu C.W., Sun F.C., Cho J.H., Lin C.C., Liu P.F., Chen P.Y., Chang M.D., Fu H.W., Lai Y.K. GRP78 and Raf-1 cooperatively confer resistance to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:627–635. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z., Wang M., Carr B.I. Hepatocyte growth factor enhances protein phosphatase Cdc25A inhibitor compound 5-induced hepatoma cell growth inhibition via Akt-mediated MAPK pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203:510–519. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilhelm S., Carter C., Lynch M., Lowinger T., Dumas J., Smith R.A., Schwartz B., Simantov R., Kelley S. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:835–844. doi: 10.1038/nrd2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordan J.D., Kennedy E.B., Abou-Alfa G.K., Beg M.S., Brower S.T., Gade T.P., Goff L., Gupta S., Guy J., Harris W.P., Iyer R., Jaiyesimi I., Jhawer M., Karippot A., Kaseb A.O., Kelley R.K., Knox J.J., Kortmansky J., Leaf A., Remak W.M., Shroff R.T., Sohal D.P.S., Taddei T.H., Venepalli N.K., Wilson A., Zhu A.X., Rose M.G. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:4317–4345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian N., Wu D., Tang M., Sun H., Ji Y., Huang C., Chen L., Chen G., Zeng M. RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Open Med (Wars) 2020;15:167–174. doi: 10.1515/med-2020-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dougherty M.K., Müller J., Ritt D.A., Zhou M., Zhou X.Z., Copeland T.D., Conrads T.P., Veenstra T.D., Lu K.P., Morrison D.K. Regulation of Raf-1 by direct feedback phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Neill E., Rushworth L., Baccarini M., Kolch W. Role of the kinase MST2 in suppression of apoptosis by the proto-oncogene product Raf-1. Science. 2004;306:2267–2270. doi: 10.1126/science.1103233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andreu-Pérez P., Esteve-Puig R., de Torre-Minguela C., López-Fauqued M., Bech-Serra J.J., Tenbaum S., García-Trevijano E.R., Canals F., Merlino G., Avila M.A., Recio J.A. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 regulates ERK1/2 signal transduction amplitude and cell fate through CRAF. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra58. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes S.D., Liu H., MacDonald E., Sanderson C.M., Coulson J.M., Clague M.J., Urbé S. Direct and indirect control of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-associated components, BRAP/IMP E3 ubiquitin ligase and CRAF/RAF1 kinase, by the deubiquitylating enzyme USP15. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:43007–43018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jang E.R., Jang H., Shi P., Popa G., Jeoung M., Galperin E. Spatial control of Shoc2-scaffold-mediated ERK1/2 signaling requires remodeling activity of the ATPase PSMC5. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:4428–4441. doi: 10.1242/jcs.177543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su S., Di Poto C., Roy R., Liu X., Cui W., Kroemer A., Ressom H.W. Long-term culture and characterization of patient-derived primary hepatocytes using conditional reprogramming. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2019;244:857–864. doi: 10.1177/1535370219855398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan J., Tan L., Yin Z., Zhu W., Tao K., Wang G., Shi W., Gao J. MIR17HG-miR-18a/19a axis, regulated by interferon regulatory factor-1, promotes gastric cancer metastasis via Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:454. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1685-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan L., Yuan J., Zhu W., Tao K., Wang G., Gao J. Interferon regulatory factor-1 suppresses DNA damage response and reverses chemotherapy resistance by downregulating the expression of RAD51 in gastric cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:1255–1270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan J., Tan L., Yin Z., Tao K., Wang G., Shi W., Gao J. GLIS2 redundancy causes chemoresistance and poor prognosis of gastric cancer based on co-expression network analysis. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:191–201. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan J., Tan L., Yin Z., Tao K., Wang G., Shi W., Gao J. Bioinformatics analysis identifies potential chemoresistance-associated genes across multiple types of cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:2576–2583. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.