Abstract

Introduction

Australians have substantial out-of-pocket (OOP) health costs compared with other developed nations, even with universal health insurance coverage. This can significantly affect access to care and subsequent well-being, especially for priority populations including those on lower incomes or with multimorbidity and chronic illness. While it is known that high OOP healthcare costs may contribute to poorer health outcomes, it is not clear exactly how these expenses are experienced by people with chronic illnesses. Understanding this may provide critical insights into the burden of OOP costs among this population group and may highlight policy gaps.

Method and analysis

A systematic review of qualitative studies will be conducted using Pubmed, CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), Cochrane Library, PsycINFO (Ovid) and EconLit from date of inception to June 2022. Primary outcomes will include people’s experiences of OOP costs such as their preferences, priorities, trade-offs and other decision-making considerations. Study selection will follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and methodological appraisal of included studies will be assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. A narrative synthesis will be conducted for all included studies.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was not required given this is a systematic review that does not include human recruitment or participation. The study’s findings will be disseminated through conferences and symposia and shared with consumers, policymakers and service providers, and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42022337538.

Keywords: health economics, health policy, quality in health care, systematic review, qualitative

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review protocol follows guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis and Cochrane handbook.

The systematic review addresses a gap in the literature through investigating how out-of-pocket costs affect the subjective experience of people with chronic diseases.

Limitations may include a scarcity of studies or low-quality evidence exploring the qualitative experience of out-of-pocket costs in Australians with chronic diseases.

The data analysed may not be representative of the general Australian population due to detection, selection and publication bias or limited studies.

This systematic review will be limited to Australian studies published in English.

Introduction

Even with Medicare, a universal healthcare insurance coverage, Australians have significant out-of-pocket (OOP) health costs compared with other countries with similar economies.1–3 The impact of these expenses can be substantial and disproportionally affect the well-being of priority populations, including those with chronic illnesses and disabilities.4–7 Yet while OOP healthcare costs affect a large portion of Australians, including those with chronic diseases, little is known about their experiences with these costs, including any variations between income groups; for example, what trade-offs do people make to pay for healthcare and medicines? Understanding this is crucial to the provision of equitable healthcare and addressing potential policy gaps.

OOP health costs are the most direct way in which the financial impact of a medical condition is felt. Australia has consistently high OOP costs for individuals compared with similar economies. Australia’s OOP expenditure as a proportion of health spending is ranked 16th highest among the 34 high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members at 14.9%.8 This is substantially greater than countries such as the USA (9.9%), UK (12.3%), Canada (12.6%) and New Zealand (12.9%).8

The impact of these OOP costs is likely to only grow in significance given historical data indicate that OOP health costs in Australia have been increasing since 1984.9 More recently, from 2009 to 2010 to 2015 to 2016 OOP household healthcare expenditure increased at a greater rate than total household expenditure at 3.8% per annum and 2.4% per annum, respectively.10 This growth in OOP expenditure has been largely attributed to rising private health insurance premiums, which make up the largest proportion of household OOP expenses (40.6%), followed by copayments towards health professionals (28.3%) and therapeutic products including subsidised medicines (20.4%).10 The impact of these increasing costs is unclear but may include households foregoing health insurance as demonstrated elsewhere in the world.11 In 2009, the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission recommended maintaining existing balances in Australian healthcare spending derived from taxation, private health insurance and OOP contribution.12 Exploring how OOP health costs impact vulnerable populations, including those living with chronic health conditions or from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, will help us better understand the implications of such recommendations and possibly encourage amendments.

The burden of OOP health costs is not distributed equitably. People with chronic illnesses tend to be older, have lower incomes, higher healthcare costs and spend a greater proportion of their incomes on healthcare.13–16 Moreover, chronic conditions compound existing levels of financial stress13 with the literature indicating that each additional chronic ailment increases the likelihood of severe financial burden by almost 50%.14 These high costs are the product of rising co-payments, private medical consultations and inadequately subsidised health support associated with chronic diseases.7 17

Such financial burdens have enduring individual and systemic effects. Both Australian18 and international studies associate a pattern of decreased adherence to medications with increased OOP costs19–21 and the opposite with reduced OOP costs.22 Australian research suggests that up to 14% of the population and 24% of those with chronic health concerns forgo recommended healthcare due to cost23; this is consistent with international studies.24–26 These statistics highlight the need to further stratify and understand why certain populations are disproportionally affected by OOP healthcare costs.

Of note, while the literature has associated high OOP costs with treatment non-adherence and increased hospitalisations,27 comorbidities28 and significant systemic economic burden,29 30 the aspect of care most affected by OOP costs has been disputed. Some studies suggest that safety net schemes from Medicare, Australia’s publicly funded universal healthcare insurance scheme, are ineffective due to the need for recipients to pay beyond an annual OOP threshold and the limited coverage of medical items.31 32 Under these safety net schemes, Australians are divided into two key groups, concession card holders, which includes pensioners and low-income populations and general patients. Each medication costs up to US$6.80 for concession card holders and US$42.50 for general patients until they meet a threshold of US$244.80 and US$1457.10, respectively, following which concession card holders receive fully subsided medications while general patients pay a reduced cost of US$6.80 per prescription.33 Other studies suggest only certain aspects of care are vulnerable to OOP costs with bulk billing practises mitigating financial burden as a barrier to receiving primary healthcare.34 35

We aim to elucidate how OOP costs of healthcare and medicines are experienced by Australians with chronic illnesses and their preferences in managing these costs. Exploring these experiences will provide critical insights into decision-making among Australians with chronic disease and highlight important policy gaps.

Methods and analysis

Protocol development

This study protocol is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews as described elsewhere.36 37 The protocol for this review is registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022337538).

Search strategy

In the interest of maintaining reproducibility and transparency, this search strategy was developed in accordance with the PRISMA-P checklist (see online supplemental file 1).36 Search terms followed a CHIP (context, how, issues, population) framework as described elsewhere.38 Five databases including Pubmed, CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), Cochrane Library, PsycINFO (Ovid) and EconLit will be systematically searched from their inception to 29 June 2022 for the primary source of literature. In addition, the reference lists of selected studies and review articles will be searched.

bmjopen-2022-065932supp001.pdf (81.8KB, pdf)

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with team members using an iterative approach. Search terms were developed using the CHIP framework and combined using Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’. An initial exploratory search was performed on all databases mentioned previously plus Proquest. The returned results demonstrated that some relevant papers that were disease specific (eg, cancer) did not include the term ‘chronic disease’ and that including this as a search term would limit results and exclude relevant literature. Proquest returned an unmanageable amount of results of which many were irrelevant following a check of the initial 100 results, and relevant studies were identified in the other databases. The search strategy was updated based on our exploratory search results—‘chronic disease’ was removed as a search term and Proquest was excluded as a database.

The final search terms are as follows: ((Interview*) OR (survey*) OR (qualitative)) AND ((‘out of pocket’) OR (‘out-of-pocket’) OR (‘financial burden*’) OR (‘financial hardship*’) OR (‘health expenditure*’) OR (‘high cost*’) OR (‘financial toxicity’)) AND ((experience*) OR (perception*) OR (attitude*) OR (view*)) AND (Australia*). The following limits were applied where stratification tools were available: English language, geographic subset of Australia or New Zealand (it was not possible to select only Australia), human studies, research articles, scholarly journals. In Cochrane Library, only trials were considered. No restriction was placed for the date.

The final search string that will be used for the literature search to be conducted on the 29 of June 2022 is documented in table 1.

Table 1.

Search string conducted on CINAHL complete (EBSCO)

| Search number | Query | Search details |

| 1 | Interview* | Interview, interviews, interviewing, interviewed |

| 2 | Survey* | Survey, surveys |

| 3 | Qualitative | Qualitative |

| 4 | ‘out of pocket’ | out of pocket |

| 5 | ‘out-of-pocket’ | out-of-pocket |

| 6 | ‘financial burden*’ | financial burden, financial burdens |

| 7 | ‘financial hardship*’ | financial hardship, financial hardships |

| 8 | ‘health expenditure*’ | Health expenditure, health expenditures |

| 9 | ‘high cost*’ | High cost, high costs, high costing, high costed |

| 10 | (‘financial toxicity’)) | Financial toxicity |

| 11 | AND ((experience*) OR | Experience, experiences, experienced, experiencing |

| 12 | (perception* | Perception, perceptions |

| 13 | (attitude*) OR | Attitude, attitudes |

| 14 | (view*)) | View, views, viewing, viewed |

| 15 | (Australia*) | Australia, Australian |

| 16 | #1 OR #2 OR # 3 | Interview OR interviews OR interviewing, interviewed OR survey OR surveys OR qualitative |

| 17 | #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 | out of pocket OR out-of-pocket OR financial burden OR financial burdens OR financial hardship OR financial hardships OR health expenditure OR health expenditures OR high cost OR high costs OR high costing OR high costed OR financial toxicity |

| 18 | #11 or #12 OR #13 OR #14 | Experience OR experiences OR experienced OR experiencing OR perception OR perceptions OR attitude OR attitudes OR view OR views OR viewing OR viewed OR viewership OR viewer |

| 11 | #16 AND #17 AND #18 AND #15 | (Interview OR interviews OR interviewing, interviewed OR survey OR surveys OR qualitative) AND (out of pocket OR out-of-pocket OR financial burden OR financial burdens OR financial hardship OR financial hardships OR health expenditure OR health expenditures OR high cost OR high costs OR high costing OR high costed OR financial toxicity) AND (experience OR experiences OR experienced OR experiencing OR perception OR perceptions OR attitude OR attitudes OR view OR views OR viewing OR viewed OR viewership OR viewer) AND (Australia, Australian) |

Restrictions: Boolean/phrase, also search within the full text of the articles, Full text available, English language, research article, Scholarly (peer-reviewed journals), Human, Geographic subset—Australia and NZ, Publication type: all.

Study selection

Search results will be uploaded to, and managed from, Covidence, a workflow platform which allows for collaborators to review uploaded studies while limiting bias.39

The criterion for selecting studies is described in table 2. As described earlier, a broader search strategy will be implemented that excludes the term ‘chronic disease’ as it was determined that including the term may limit the strength of the search and its findings. Data allowing, this search will be narrowed to only include studies referring to populations with chronic illness. All studies describing how OOP costs affect individuals with chronic diseases, regardless of the pathology type, will be selected. The exclusion criteria will be review articles, studies written in language other than English or those describing populations outside Australia.

Table 2.

The inclusion criteria as described in a CHIP format, and the exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Context | Australian public health systems | – |

| How | Qualitative studies | – |

| Issues | Experiences of out-of-pocket costs | – |

| Populations | Adults living in Australian who have or are managing one or more chronic diseases | – |

| Study design | Review articles, commentaries, letters, issue briefs, editorials, poster presentations or conference papers | |

| Language | English | – |

| Setting | Australia | – |

| Timing | From database inception to 29 June 2022 | – |

CHIP, context, how, issues, population.

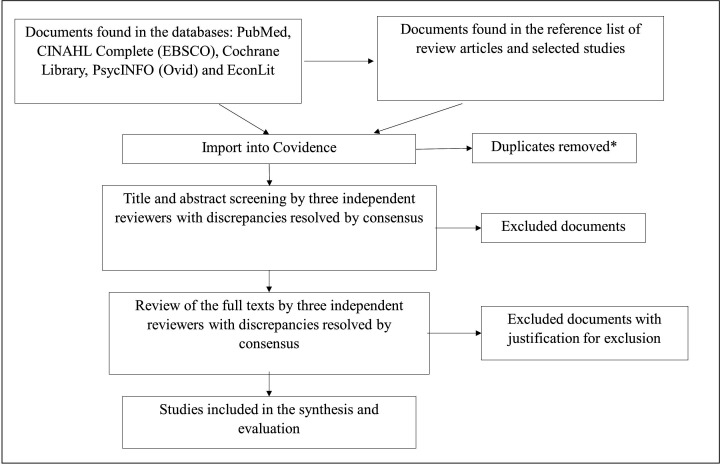

The planned selection process is illustrated in figure 1. Three members of the research team (ST-LW, AP, JD) will independently review the studies to determine their inclusion in the review. A preliminary screening will be based on the study title and abstract. The full text of studies included from this stage will then be screened. Conflicts will be resolved through consensus between the three reviewers. If a study is excluded in the selection phase, the reason for exclusion will be recorded. During this process, no reviewers will be blinded to the study types, journals, and authors.

Figure 1.

The planned selection process. *Duplicates will be removed in endnote prior to importing references into Covidence for screening and selection.

Data extraction

A data extraction table will be developed and piloted. Two independent reviewers will extract data from five studies each and compare their results to establish agreement and the validity of the extraction tool.

Data items to be extracted will include:

Identification of the study (article title, journal, authors, year, citation, host institution (research centre/university/hospital/organisation), conflict of interest, funding/sponsorship),

Methodological description (study purpose, study design, demographics of participant including chronic illness and socioeconomic status or income, recruitment process, inclusion, exclusion criteria, statistical analysis),

Main findings (people’s experiences of OOP costs including their preferences, priorities, trade-offs and other decision-making considerations).

If the outcome of a study is unclear, the authors will be contacted for interpretation or clarification. Any disagreements will be resolved through discussion and consensus between the three reviewers.

Quality appraisal

Risk of bias will be assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist40 by two independent reviewers (ST-LW and JD). CASP is a standardised appraisal tool which provides a systematic assessment of the reliability and validity of published papers.40 Discrepancies will be resolved in discussion with a third reviewer (AP).

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

Interpretation of the data will be discussed among the study team. A narrative approach will be taken to synthesising data using the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines.41 This will include a detailed, written commentary on extracted data related to outcomes as listed in table 2. Doing so will further our understanding of how people with chronic disease experience and manage the OOP costs of healthcare.

Any significant changes made to this protocol will be documented and published with the findings of the systematic review.

Patient and public involvement

We follow a coproduction approach in all our work. The research team includes health services researchers, with backgrounds in nursing, medicine, sociology, public health and epidemiology. The team also includes four people who are not academics and are living with chronic disease (one of whom is a coauthor on this protocol), and who will be involved in the interpretation and analysis of findings and study write up.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required given this is a systematic review that does not include human recruitment or participation. The study’s findings will be disseminated through conferences and symposia and shared with consumer groups, policymakers and service providers, and published in a peer-reviewed journal,

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @JaneODes

Contributors: ST-LW prepared the study protocol and drafted the manuscript. JD and AP supervised the procedure of developing the study protocol. HDL, DB and VF reviewed the study protocol. All authors were involved in discussions related to the study design and concept. The manuscript was revised by all authors.

Funding: This review is part of the 'The Real Price of Health: Experiences of Out-of-Pocket Costs in Australia' project funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (Grant ID: DE220100663) and the Australian National University. Funding officials are not involved in any part of the review including protocol development, data selection, synthesis, reporting and publishing of the results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Laba T-L, Usherwood T, Leeder S, et al. Co-payments for health care: what is their real cost? Aust Health Rev 2015;39:33–6. 10.1071/AH14087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, et al. How health insurance design affects access to care and costs, by income, in eleven countries. Health Aff 2010;29:2323–34. 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health AIo, Welfare . Health expenditure Australia 2009–10 AIHW Canberra; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jan S, Essue BM, Leeder SR. Falling through the cracks: the hidden economic burden of chronic illness and disability on Australian households. Med J Aust 2012;196:29–31. 10.5694/mja11.11105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Y, Atun R, Anindya K, et al. Medical costs and out-of-pocket expenditures associated with multimorbidity in China: quantile regression analysis. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kočiš Krůtilová V, Bahnsen L, De Graeve D. The out-of-pocket burden of chronic diseases: the cases of Belgian, Czech and German older adults. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:239. 10.1186/s12913-021-06259-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essue B, Kelly P, Roberts M, et al. We can't afford my chronic illness! The out-of-pocket burden associated with managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in western Sydney, Australia. J Health Serv Res Policy 2011;16:226–31. 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.OECD Data . Health spending (indicator) [Internet], 2022. Available: https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm [Accessed 07 Sep 2022].

- 9.Statistics ABo . Household expenditure survey, Australia: summary of results abs.gov.au: Australian Bureau of statistics, 2017. Australian Bureau of statistics. Available: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/finance/household-expenditure-survey-australia-summary-results/latest-release#data-download

- 10.Yusuf F, Leeder S. Recent estimates of the out-of-pocket expenditure on health care in Australia. Aust Health Rev 2020;44:340–6. 10.1071/AH18191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabani J, Guinness L. Households forgoing healthcare as a measure of financial risk protection: an application to Liberia. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:193. 10.1186/s12939-019-1095-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett C. National health and hospitals reform Commission: a healthier future for all Australians. final report of the. Canberra: National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter A, Islam MM, Yen L, et al. Affordability of out-of-pocket health care expenses among older Australians. Health Policy 2015;119:907–14. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McRae I, Yen L, Jeon Y-H, et al. Multimorbidity is associated with higher out-of-pocket spending: a study of older Australians with multiple chronic conditions. Aust J Prim Health 2013;19:144–9. 10.1071/PY12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yusuf F, Leeder SR. Can't escape it: the out-of-pocket cost of health care in Australia. Med J Aust 2013;199:475–8. 10.5694/mja12.11638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callander EJ, Fox H, Lindsay D. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in Australia: trends, inequalities and the impact on household living standards in a high-income country with a universal health care system. Health Econ Rev 2019;9:10. 10.1186/s13561-019-0227-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essue BM, Wong G, Chapman J, et al. How are patients managing with the costs of care for chronic kidney disease in Australia? A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2013;14:5. 10.1186/1471-2369-14-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hynd A, Roughead EE, Preen DB, et al. The impact of co-payment increases on dispensings of government-subsidised medicines in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:1091–9. 10.1002/pds.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, et al. The epidemiology of prescriptions abandoned at the pharmacy. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:633–40. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-10-201011160-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinnott S-J, Buckley C, O'Riordan D, et al. The effect of copayments for prescriptions on adherence to prescription medicines in publicly insured populations; a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e64914. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laba T-L, Cheng L, Kolhatkar A, et al. Cost-related nonadherence to medicines in people with multiple chronic conditions. Res Social Adm Pharm 2020;16:415–21. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson S, Stokes JP. Impact of out-of-pocket costs on patient initiation, adherence and persistence rates for patients treated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor medicines. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020;48:477–85. 10.1111/ceo.13706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, et al. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the United States compared to ten other countries. Health Aff 2013;32:2205–15. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiil A, Houlberg K. How does copayment for health care services affect demand, health and redistribution? A systematic review of the empirical evidence from 1990 to 2011. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:813–28. 10.1007/s10198-013-0526-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remler DK, Greene J. Cost-sharing: a blunt instrument. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30:293–311. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lago-Hernandez C, Nguyen NH, Khera R, et al. Cost-related nonadherence to medications among US adults with chronic liver diseases. Mayo Clin Proc 2021;96:2639–50. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muszbek N, Brixner D, Benedict A, et al. The economic consequences of noncompliance in cardiovascular disease and related conditions: a literature review. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:338–51. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01683.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaul S, Avila JC, Mehta HB, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 2017;123:2726–34. 10.1002/cncr.30648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe JH, McInnis T, Hirsch JD. Cost of prescription drug-related morbidity and mortality. Ann Pharmacother 2018;52:829–37. 10.1177/1060028018765159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu ZK, Xiong X, Brown J, et al. Impact of cost-related medication nonadherence on economic burdens, productivity loss, and functional abilities: management of cancer survivors in Medicare. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:706289. 10.3389/fphar.2021.706289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Health expenditure Australia 2019-20. Canberra: AIHW, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duckett S, Willcox S. The Australian health care system Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Care DoHaA . About the PBS: Australian Government, 2022. Available: https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/about-the-pbs [Accessed 17 Sep 22].

- 34.Song HJ, Dennis S, Levesque J-F, et al. What matters to people with chronic conditions when accessing care in Australian general practice? A qualitative study of patient, carer, and provider perspectives. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:1–13. 10.1186/s12875-019-0973-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuesta-Briand B, Saggers S, McManus A. 'It still leaves me sixty dollars out of pocket': experiences of diabetes medical care among low-income earners in Perth. Aust J Prim Health 2014;20:143–50. 10.1071/PY12096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Julian Higgins JT, Chandler J, Cumpston M, et al. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 2022; version 6.3. Available: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- 38.Forrester MA. Doing qualitative research in psychology : a practical guide. Los Angeles [i.e. Thousand Oaks, Calif.]: SAGE Publications, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veritas Health Innovation . Covidence systematic review software Melbourne, Australia. Available: www.covidence.org

- 40.Programme CAS. CASP systematic review checklist, 2022. Available: https://casp-uk.net/https://casp-uk.net/

- 41.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Systematic reviews. University of York: York Publishing Services Ltd, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-065932supp001.pdf (81.8KB, pdf)