Abstract

Objective

Supervised exercise therapy (SET) is the first line treatment for intermittent claudication owing to peripheral arterial disease. Despite multiple randomized controlled trials proving the efficacy of SET, there are large differences in individual patient's responses. We used plasma metabolomics to identify potential metabolic influences on the individual response to SET.

Methods

Primary metabolites, complex lipids, and lipid mediators were measured on plasma samples taken at before and after Gardner graded treadmill walking tests that were administered before and after 12 weeks of SET. We used an ensemble modeling approach to identify metabolites or changes in metabolites at specific time points that associated with interindividual variability in the functional response to SET. Specific time points analyzed included baseline metabolite levels before SET, dynamic metabolomics changes before SET, the difference in pre- and post-SET baseline metabolomics, and the difference (pre- and post-SET) of the dynamic (pre- and post-treadmill).

Results

High levels of baseline anandamide levels pre- and post-SET were associated with a worse response to SET. Increased arachidonic acid (AA) and decreased levels of the AA precursor dihomo-γ-linolenic acid across SET were associated with a worse response to SET. Participants who were able to tolerate large increases in AA during acute exercise had longer, or better, walking times both before and after SET.

Conclusions

We identified two pathways of relevance to individual response to SET that warrant further study: anandamide synthesis may activate endocannabinoid receptors, resulting in worse treadmill test performance. SET may train patients to withstand higher levels of AA, and inflammatory signaling, resulting in longer walking times.

Clinical Relevance

This manuscript describes the use of metabolomic techniques to measure the interindividual effects of SET in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD). We identified high levels of AEA are linked to CB1 signaling and activation of inflammatory pathways. This alters energy expenditure in myoblasts by decreasing glucose uptake and may induce an acquired skeletal muscle myopathy. SET may also help participants tolerate increased levels of AA and inflammation produced during exercise, resulting in longer walking times. This data will enhance understanding of the pathophysiology of PAD and the mechanism by which SET improves walking intolerance.

Keywords: Metabolomics, Peripheral artery disease, Lipid mediators, Supervised exercise therapy, Endocannabinoid signaling

Article Highlights.

-

•

Type of Research: Human study

-

•

Key Findings: High levels of change in anandamide across supervised exercise therapy (SET) were associated with a worse response to SET when observing differences in pre- and post-SET baseline metabolomics. Large changes arachidonic acid and decreased levels of arachidonic acid precursor dihomo-γ-linolenic acid across SET were associated with a worse response to SET when observing the difference (pre- and post-SET) of the dynamic (pre- and post-treadmill) metabolite changes.

-

•

Take Home Message: Changes in circulating metabolite patterns associate with individual response to SET. SET may help to train patients withstand higher levels of inflammatory signaling and permit them to walk for longer periods of time.

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is progressive atherosclerotic disease of the aorta and lower extremities that affects more than 200 million people worldwide.1 Insufficient blood flow to the lower extremities leads to ischemia-driven symptoms ranging from intermittent claudication to tissue loss. The physical activity limitation of patients with PAD results in functional impairment, loss of mobility, and decreased quality of life.2,3

Supervised exercise therapy (SET) is the first line treatment for individuals with intermittent claudication.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Other treatment options for PAD include a combination of SET, medications, lifestyle modification such as smoking cessation and weight loss, and revascularization.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 The efficacy of SET in patients with PAD dates back to 1966, when Larsen and Lassen9 demonstrated that 6 months of intermittent walking therapy improved walking time to onset of discomfort and peak walking time (PWT), which represents claudication-limited exercise tolerance. There have been multiple clinical trials comparing the benefits of SET with and without revascularization versus optimized medical therapy.6,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 However, there has not been consistent evidence for substantial benefit using one intervention strategy over another owing to interindividual variability in response to therapies.20, 21, 22

The pathophysiology underlying not only functional decline, but also the effects of exercise observed in patients with PAD, is complex and poorly understood.23 It is thought that both structural and metabolic disarray in calf skeletal muscle contributes to walking impairment, pain, and functional decline. Although SET does not affect plaque morphology and has uncharacterized effects of blood flow, there have been several proposed mechanisms of action: increased calf blood flow via the microvasculature; improved endothelial function and subsequent improved vasodilatation; decreased inflammation; improvements in muscle structure, strength, and endurance; vascular angiogenesis; improved mitochondrial function; and skeletal muscle metabolism through lipid-based signaling.4,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Despite the fact that metabolomics have been used to investigate some of these mechanisms,31,32 metabolomics have not been leveraged to examine the response to exercise training in patients with PAD.

In this study, metabolomic and lipidomic techniques were used to measure the effects of SET on primary metabolites, complex lipids, and lipid mediators. Through this, we were able to identify metabolites associated with interindividual variability in the response of individuals with PAD to SET. This insight will enhance our understanding of the pathophysiology of lower extremity symptoms in PAD, the mechanism by which SET improves walking intolerance, and provide insight on pathways to target for clinical intervention.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of blood samples drawn as a part of a clinical trial as described elsewhere in this article. Human subjects protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board for and carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants provided written informed consent before inclusion in this study.

Study design

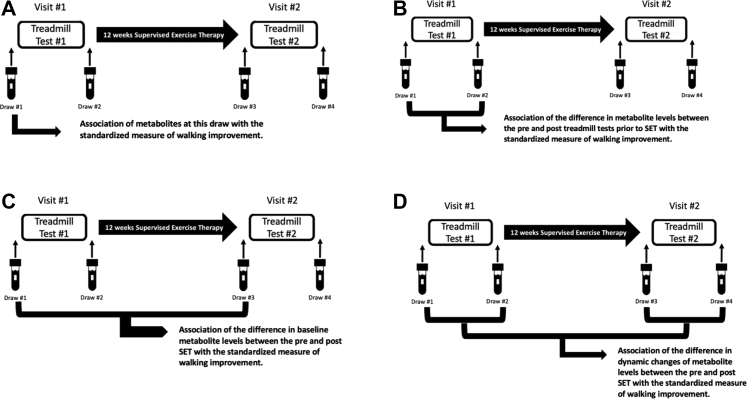

The goal of this study was to identify metabolites that were associated with individual responses to SET. We used data and plasma samples from a previously completed randomized control trial of SET comprised of individuals with peripheral artery disease, as defined by ankle brachial indices of 0.4 or more and of 0.8 or less and the presence of classic claudication symptoms, that were randomized to 12 weeks of a standard, validated SET program or usual medical care.33 Twelve weeks was selected as the appropriate SET time frame per clinical practice guidelines for standard medical treatment of PAD34 and all patients who did not undergo SET were excluded from this analysis. Before initiating and on completion of the exercise program, participants underwent a Gardner graded treadmill walking test to determine PWT.35 Venous blood was sampled before and after each treadmill test using sodium citrate collection tubes, and platelet free plasma was stored at –80°C (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Scheme for defining metabolites of significant interest. Visit #1 included a draw before the first treadmill test (draw 1) and after the first treadmill test (draw 2). Visit #2 after supervised exercise therapy (SET) included a draw before the second treadmill test (draw 3) and after the second treadmill test (draw 4). (A) Baseline metabolomics pattern before SET. Illustration of the association of baseline metabolite levels at visit 1 measured before SET at draw 1 with interindividual response to SET. (B) Dynamic metabolomics changes before SET. Illustration of the association of dynamic metabolite levels at visit 1 measured before SET at draw 1 and draw 2 with interindividual response to SET. (C) Difference in pre- and post-SET baseline metabolomics. Illustration of the association of the difference in baseline metabolite levels from plasma samples collected before (visit 1 draw 1) and after (visit 2 draw 3) 12 weeks of SET with interindividual response to SET. (D) The difference pre-SET (visit 1) and post-SET (visit 2) of the dynamic pretreadmill (draw 1 and draw 3) and post-treadmill (draw 2 and draw 4). Illustration of the impact of SET on the dynamic changes in metabolite levels that occur over the course of the Gardner treadmill test associates with individual response to SET.

Individuals who were randomized to the exercise program arm, completed at least 80% of prescribed sessions, and had all four plasma samples available were selected for metabolic and lipidomic analysis. Forty-three participants in the completed study met these criteria. Based on available resources, the 40 participants who completed the greatest number of training sessions were selected. This sampling performed within the existing clinical trial lends itself to selection bias of who participated in the trial.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the standardized change in PWT that occurred between the Gardner treadmill test administered before and after SET as a measure of a participant's response to SET. To derive this, a generalized linear model (GLM) was constructed that modeled the log-transformed PWT (log[PWT]) measured on the post-SET treadmill test based on log(PWT) from the pre-SET treadmill test. In the model, the slope (β) for the pretraining log(PWT) represents the average effect of training on the change in log(PWT) across the cohort. Standardized individual responses are represented by the studentized residuals extracted from the model for each participant. The resultant quantity represents an individual's personal change in PWT as a result of SET, as compared to the mean group response (Supplementary Fig 1). Negative values represent a less than average increase in PWT as a result of SET and positive values represent a greater than average increase in PWT as a result of SET.

Metabolomic and lipidomic analyses

The plasma samples of the 40 participants were analyzed using one targeted and two untargeted metabolite panels. Primary metabolites were measured on a Leco Pegasus IV, gas chromatography coupled to time-of-flight mass spectrometry mass spectrometer with details on sample preparation, derivatization, chromatography parameters, data processing, compound identification, and data curation given in Fiehn.36 Complex lipids were measured on an Agilent 6530 Liquid Chromatography quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry instrument in positive and negative electrospray mode as given in details in Tsugawa et al37 and Cajka et al.38 Lipid mediators were separated on a 2.1 × 150-mm 1.7-μm ethylene bridged hybrid C18 column and detected by electrospray ionization with multi reaction monitoring on a API 6500 quadrupole ion trap and quantified against 7-9 point calibration curves of authentic standards using modifications of previously reported methods.39 Please see the Supplementary Methods for detailed methodology.

Data processing

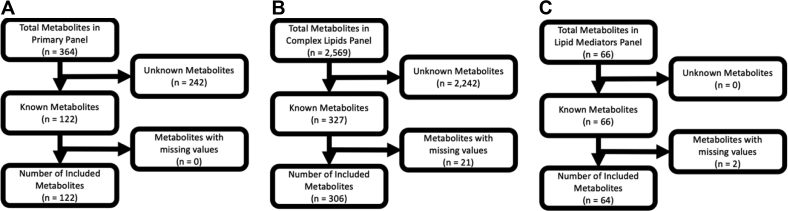

Any metabolite that was not able to be quantified for every time point for every patient in this cohort was removed altogether from analysis to prevent any bias introduced by testing error and to maintain an adequate sample size for analysis. This resulted in a total of 2507 metabolites with incomplete data across samples removed from analysis. To focus on biological mechanisms, only peaks corresponding to known metabolites were considered in the analysis, for a total of 122 known metabolites in the primary metabolite panel, 306 metabolites in the complex lipids panel, and 64 metabolites in the lipid mediators panel (Fig 2). Raw metabolite levels were natural log transformed and pareto scaled.

Fig 2.

Flowchart of metabolites excluded from analysis. Metabolites in (A) primary, (B) complex lipid, and (C) lipid mediator metabolites were restricted to known metabolites with 0 missing observations. All metabolite levels were individually natural log transformed and pareto scaled before all analysis.

Metabolites were annotated with a super class, main class, and sub class by compound name using the RefMet database from the University of California San Diego Metabolomics Workbench.40 The most specific classification that yielded groups of four or more metabolites in each dataset was used for hypergeometric enrichment. Super class designations were used for the primary and the complex lipids, main class designation was used for the lipid mediators.

Association testing

The association of metabolites with interindividual variability in response to SET was determined using multiple models to maximize discovery while minimizing false positives: repeated measures GLM, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression (LASSO), elastic net, random Forest, and support vector regressions. The different models each have unique attributes with distinct advantages and limitations: GLM are easy to interpret and computationally efficient, but do not perform variable selection and cannot handle situations with more predictors than cases. LASSO and elastic net are modifications of the GLM that introduce a penalty variable to perform feature selection and can thus handle situations with more predictors than cases but differ in how they assign the penalty variable; LASSO eliminates noninformative features, whereas elastic net does not. Disadvantages include unstable models owing to the requirement to bootstrap data. Random Forests is a decision tree approach that deals well with high dimensional data and is robust to outliers, but is computationally intensive and the effect estimates do not contain information about directionality. Support vector regression performs well with large numbers of predictor variables, but is not robust to noise in the dataset and does not produce error estimates. By using an integrative approach of these complementary approaches, we sought to balance the methodical biases of each approach.41, 42, 43

Significant thresholds

To limit detection of false positives, metabolites of significant interest were defined as being nominally significant on two or more models or experiment wide significant on one model. For glm, random Forest, and support vector regressions nominal significance was defined at a P value of less than .05. For LASSO and elastic net, metabolites with coefficients not equal to zero were considered to have a nominally significant association. For all tests, experiment wide significance was defined as a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05 for the number of known metabolites in the analyzed panel.

Hypergeometric enrichment

Hypergeometric enrichment was used to identify overly represented classes of metabolites. The hypergeometric distribution was determined based on the total number of metabolites, the number of metabolites of interest, and the number of metabolites in the group of interest calculated using the ‘phyper’ command in base R. Nominal significance was defined as a P value of less than .05. Multiple testing correction was performed using a Benjamini-Hochberg and experiment wide significance was defined as a FDR of less than 0.05.

Results

Trial design, demographic characteristics, and response to SET

This study was conducted on a subset of individuals enrolled in a randomized trial of SET.33,44 To identify metabolites associated with the interindividual variability in the response to SET, 40 participants who were randomized to the exercise arm and completed at least 80% of prescribed sessions were selected for metabolite analysis. These participants were a median of 65 years old (interquartile range [IQR], 61-69 years) with a median body mass index of 28 kg/m2 (IQR, 26-3028 kg/m2) and 75% were male (Table I). The median PWTs before and after SET were 8.22 minutes (IQR, 4.81-11.7 minutes) and 15.0 minutes (IQR, 9.20-19.2 minutes), respectively. The median change in PWT was relatively modest (5.88 minutes; IQR, 1.65-10.11 minutes), with a large range (1.96-35.2 minutes), suggesting individual level effects of SET training on walking performance. No demographic factors demonstrated an experiment wide significant association with PWT (Table I). We hypothesized that metabolite levels, static or dynamic, associate with an individual's response to SET.

Table I.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n = 40) who had plasma samples drawn before and after treadmill testing

| Overall (n = 40) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.0 [60.8, 69.3] |

| Gender | |

| Male | 30 (75.0) |

| Female | 10 (25.0) |

| BMI | 28.3 [25.8-30.1] |

| Tobacco use | |

| Never | 5 (12.5) |

| Former | 19 (47.5) |

| Recently quit (<3 mo) | 6 (15.0) |

| Current | 10 (25.0) |

| Diabetes | |

| Yes | 18 (45.0) |

| No | 22 (55.0) |

| Hypertension | |

| Yes | 36 (90.0) |

| No | 4 (10.0) |

| Hyperlipidemia | |

| Yes | 32 (80.0) |

| No | 8 (20.0) |

| Pretraining ABI | 0.690 [0.605-0.763] |

| Post-training ABI | 0.750 [0.640-0.870] |

| Pretraining PWT, minutes | 8.22 [4.81-11.7] |

| Post-training PWT, minutes | 14.1 [9.20-19.2] |

| Change in PWT, minutes | 4.95 [1.18-9.47] |

ABI, Ankle-brachial index; BMI, body mass ides; PWT, peak walking time.

Values are number (%) or median (interquartile range).

To test this hypothesis, we first calculated the individual's response to SET. We modeled PWT on the treadmill test after SET based on PWT before SET using a GLM. In this model, the slope (β) of the achieved second treadmill test performance against the predicted second treadmill test performance represents the average effects of SET. To determine individual performance, we calculated the studentized residuals that capture the difference between the predicted and actual PWT on the post-SET treadmill test for each individual. We then tested the participant characteristics for an association with the studentized residual, or the standardized measure of walking improvement, to identify confounding clinical factors that contributed to the subject-level variation effects of SET (Supplementary Fig 1). Although age was nominally associated with the standardized measure of walking improvement (β = –0.05; 95% confidence interval, –0.1 to –0.01; P = .02), no demographic factors demonstrated an experiment wide significant association with the studentized residual (Supplementary Table I).

Baseline and dynamic metabolite levels measured before SET associate with interindividual response to SET

To identify baseline metabolomics pattern before SET (visit 1 draw 1) associated with interindividual differences in the response to SET (Fig 1, A), we tested the association of baseline metabolite levels (draw 1) from the first study visit with the standardized measure of walking improvement and identified a total of 32 metabolites of interest (Supplementary Fig 2; Supplementary Table II). Homogeneous nonmetal compounds (P = .02), sphingolipids (P = .05), fatty amides (P = .04), and sterol and prenol lipids (P = .03) were all nominally enriched metabolite classes (Supplementary Table III), but the significant enrichment did not persist after correcting for multiple testing.

We then examined whether dynamic changes in metabolite levels (draw 1 and draw 2) that resulted from the Gardner treadmill test before the course of 12 weeks of SET (visit 1) were associated with interindividual response to SET (Fig 1, B) and identified a total of 28 metabolites of interest (Supplementary Fig 1, A; Supplementary Table IV). The metabolite class enrichment was similar to that seen with baseline metabolites: homogeneous nonmetal compounds (P < .01; FDR q-value, 0.04), sterol and prenol lipids (P < .01; FDR q-value = 0.04), and fatty amides (P < .001; FDR q-value < 0.01) had experiment wide significant enrichment (Supplementary Table V). In all cases, the metabolites of interest in these classes were negatively associated with improvement in PWT demonstrating that large changes in these metabolite levels over the baseline treadmill test were associated with diminished response to SET.

Changes in metabolite levels that occur over the course of SET associate with individual response to SET

Changes in pre-exercise metabolite levels that occurred as a result of a 12-week course of SET (draw 3) were tested against the standardized measure of walking improvement (Fig 1, C). We first tested the association of the difference in baseline metabolite levels from plasma samples collected before and after 12-weeks of SET with standardized measure of individual improvement in PWT and identified a total of 73 metabolites of significant interest (Supplementary Fig 1, B; Supplementary Table VI) that associated with improvement in PWT. Fatty acyls (P = .05), homogeneous nonmetal compounds (P = .04), and glycerophospholipids (P = .05) were nominally enriched in this model (Supplementary Table VII), but failed to reach experiment wide significant enrichment. Organonitrogen compounds (P < .01; FDR q-value = 0.02) and fatty amides (P < .01; FDR q-value = 0.02) were enriched at an experiment-wide level. In all cases, the metabolites of interest in these classes were negatively associated with performance on the first treadmill test, meaning large increases in these metabolites after SET before an acute exercise stress were associated with diminished response to SET. These have both been previously shown to change as a result of acute exercise and effect downstream endocannabinoid signaling.45

Of particular interest, we observed that changes in pre-exercise levels of acyl ethanolamide (AcylEA) metabolites, including anandamide (AEA), linoleoyl ethanolamide, and adrenoyl-ethanolamide (C22:5n6-ethanolamide) test that occurred over the course of SET (draw 1 and draw 3) (Fig 1, C) were all negatively associated with the response to SET (Table II). In other words, the greater the SET induced increase in pre-exercise levels of plasma AcylEAs, the worse responses to SET. In addition, we saw that SET induced changes in pre-exercise levels of plasma arachidonic acid (AA) were associated with above average response to SET (Table II, Supplementary Table VI).

Table II.

Significant results relevant to pathways described

| Dataset | Metabolite | Model | Outcome | Direction of association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid mediators | AA | Draw 1 | PWT | – |

| Lipid mediators | AEA | Draw 1 | PWT | – |

| Lipid mediators | N-oleoylethanolamide | Draw 1 | PWT | – |

| Lipid mediators | Adrenoyl-ethanolamide | Draw 3 – Draw 1 | Individual response to SET | – |

| Lipid mediators | AA | Draw 3 – Draw 1 | Individual response to SET | + |

| Lipid mediators | AEA | (Draw 4 – Draw 3) – (Draw 2 – Draw 1) | Individual response to SET | – |

| Lipid mediators | AA | (Draw 4 – Draw 3) – (Draw 2 – Draw 1) | Individual response to SET | + |

AA, Arachidonic acid; AEA, acyl ethanolamide; PWT, peak walking time; SET, supervised exercise therapy.

Metabolites were analyzed in relationship to pretherapy log(PWT) and the standardized measure of individual improvement in PWT for each of the three data sets using five models: general linear model, elastic net, lasso, random Forest, and support vector machine. Metabolites of significant interest were classified as achieving nominal significance on two or more models or experiment wide significance on one model. Multiple testing correction threshold was set at a false discovery rate of 0.05 for each model and for each of the three datasets. This table includes only significant results of select metabolites.

We then tested how the impact of SET on the dynamic changes in metabolite levels (draw 2 minus draw 1 subtracted from draw 4 minus draw 3) that occur over the course of the Gardner treadmill test associates with individual response to SET (Fig 1, D). This experiment identified a total of 25 metabolites of significant interest (Supplementary Fig 1, C; Supplementary Table VIII). Carbohydrates (P < .01; FDR q-value < 0.001), glycerolipids (P = .01; FDR q-value < 0.001), and eicosanoids (P < .01; FDR q-value < 0.001) were experiment wide enriched in this model (Supplementary Table IX).

Discussion

Metabolomics has been performed on patients with PAD to identify metabolites associated with disease progression,31,32 as well as on a cohorts of healthy and insulin resistant people after exercise.46, 47, 48 However, metabolomics has not been used to examine the response to exercise training in patients with PAD. We sought to understand metabolic changes at specific time points with reference to relative improvement in treadmill performance between individuals (Fig 1). To do this, we used five different models to identify metabolites or changes in metabolites at specific time points that associate with either treadmill test performance or interindividual variability in functional performance after SET. To further understand how classes of metabolites associate with exercise, enrichment analysis was performed. Importantly, we identified metabolites involved in two skeletal muscle pathways of relevance to individual response to SET which warrant further study for potential clinical intervention: AEA signaling and AA synthesis.

AEA changes are associated with exercise tolerance

AEA is an organonitrogen compound derived from nonoxidative metabolism49 that functions as an endocannabinoid signaling molecule. In skeletal muscle, AEA exerts its effect on muscle metabolism through the membrane-bound G-proteins CB1 and CB2, leading to changes in insulin sensitivity, different patterns of glucose uptake,50 and inhibition of myotube formation.51,52 Our data and other literature support the idea that individuals with PAD who perform poorly on treadmill tests after SET have an accumulation of inflammatory byproducts resulting in increased endocannabinoid signaling.

Although AEA is generally considered anti-inflammatory, AEA signaling through CB1 receptors is can also be proinflammatory.53 Changes in circulating AEA and other AcylEAs during exercise have previously been described in healthy participants,54,55 where the plasma concentration of AEA after exercise was shown to correlate with endocannabinoid activity. Therefore, the effects of exercise on AEA levels can be directly linked to endocannabinoid signaling.56 Downstream activity of AEA signaling via the CB1 receptor has been shown to inhibit myoblast differentiation, expand the number of satellite cells, and stimulate the fast-muscle oxidative phenotype.57 Chronic CB1 receptor stimulation has also been shown to increase metabolic inflammation and inflammatory byproducts in mice by inducing glucose intolerance.58 Even in acute instances, increased CB1 activation impairs skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity, which decreases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle59,60 and may contribute to an acquired skeletal muscle myopathy.61,62

In the current study, we found that participants that had large increases in baseline AEA levels and dihomo-γ-linolenic acid levels as a result of SET did not respond as well to SET (Table II). We hypothesize that increased AEA synthesis leads to increased skeletal muscle endocannabinoid signaling, decreased energy availability, more pain, increased walking dysfunction, and decreased response to SET. However, additional focused studies are needed to mechanistically link AEA and endocannabinoid signaling with walking dysfunction in PAD and the improvements in walking distance associated with SET.

AA and chronic inflammation

The synthesis of AA is another key pathway that can contribute to the inflammatory response after exercise. AA is a polyunsaturated fatty acid present in phospholipids throughout the body, but is especially concentrated in skeletal muscle.63,64 AA generally has proinflammatory and proaggregation effects.65 In this study, we observed that large increases in baseline AA as a result of SET were associated with above average response to SET (Table II).

AA and its downstream metabolites are known to play roles in both the initiation and resolution of inflammation of several disease states, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.66 The metabolites of AA are generally inflammatory: whereas cytochrome P450-dependent epoxygenated AA metabolites are largely anti-inflammatory, the rapid breakdown of these again yields proinflammatory signals.67 AA derivatives from the lipoxygenase pathways are involved in promoting hyperalgesia and derivatives from the cyclooxygenase pathway are involved in the production of thromboxane A2 and prostaglandins,68 which contribute to an inflammatory response. Based on our findings and known AA biology, we hypothesize that SET helps to train individuals with claudication to withstand higher levels of AA and inflammatory signaling, resulting in longer walking times; however, additional experiments that investigate the AA pathway in a tissue focused manner and metabolites in this pathway are required to prove this.

It is known that PAD patients overall have increased levels of circulating inflammatory biomarkers.69 It is also known that patients are instructed to walk through the pain when inflammatory markers are presumably the highest70 to develop collateral circulation. Therefore, our findings that patients who withstand higher levels of inflammatory signaling may walk for longer periods of time seems plausible.71

Limitations

Our results must be interpreted within the context of the limitations of the study design. This study was a secondary analysis of blood samples drawn as part of a clinical trial not originally designed to investigate metabolomics and the sampling scheme and sample handling were not designed to optimize sample integrity for metabolomics: nonfasting blood samples were used for analysis and this work did not include participant diet records to control for the impact of diet on the metabolome. Furthermore, anti-inflammatory medication use was not recorded. These limitations in the experimental design would be expected to introduced noise and, thus, bias our results toward the null. Participants recruited in this cohort were not necessarily reflective of the usual treatment population of PAD: only 25% of our cohort was actively smoking; the Vascular Quality Initiative percutaneous vascular intervention cohort reports thar 47% of registrants are active smokers. This difference could reflect a recruitment bias that results from differential willingness to participate in a randomized controlled trial of SET between current smokers and current nonsmokers. Although no patient demographics collected associated with the primary outcome, this factor limits the generalizability of our study. Although this study did not have a control group, we have considered each participant's baseline metabolite levels in our analysis and examined only individual responses to SET; it is possible, however, that some of the differences observed may be due to fluctuations detected based on repeat sampling, although this factor would, again, be expected to bias the results to the null. In terms of metabolite levels, there is controversy in the literature generalizing the role of a singular metabolite with respect to overall pathway involvement: some metabolites measured are involved in multiple pathways and have multiple breakdown products with opposing effects. Therefore, it is difficult to define clearly what is and is not known. Finally, we excluded any metabolite that was incomplete across samples and, therefore, cannot comment on the significance of those metabolites. Metabolite panels did not include all metabolites in many pathways of interest, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the full regulation of the pathway. Future work is needed to better validate our metabolic patterns found in a larger participant cohort with an experimental design optimized specifically for metabolomic analysis, including fasting blood draws, monitored diet status, and records of medication intake.

Conclusions

We identified changes in circulating metabolites and metabolite patterns that associate with individual response to SET. In particular, we found two pathways, AEA signaling, and AA synthesis associated with individual response to SET which could be areas for future clinical intervention or drug development. Interestingly, both pathways are involved in inflammatory signaling suggesting SET may help participants tolerate increased inflammation produced during exercise, resulting in longer walking times.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: TRB, NLT, JM, SJR, OF, TFF, FWW, EM, JWN, SMD

Analysis and interpretation: TRB, NLT, HJC, KB, GS, RJ, EM

Data collection: EM

Writing the article: TRB, NLT

Critical revision of the article: TRB, NLT, HJC, KB, GS, RJ, JM, SJR, OF, TFF, FWW, JWN, SMD

Final approval of the article: TRB, NLT, HJC, KB, GS, RJ, JM, SJR, OF, TFF, FWW, JWN, SMD

Statistical analysis: TRB, NLT

Obtained funding: EM, SMD

Overall responsibility: SMD

TRB and NLT contributed equally to this article and share co-first authorship.

SMD and JWN contributed equally to this article and share senior authorship.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Emile Mohler passed away during the preparation of this manuscript. He was an outstanding and dedicated physician, scientist, and mentor. He is included as an author with the permission of his family.

Footnotes

Supported by funding from: the Department of Veterans Affairs awards IK2-CX001780 (S.M.D.); National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL075649-09 (E.M.); and a Pilot and Feasibility project award (S.M.D) from the NIH West Coast Metabolomics Center (O.F.). Additional support was provided by USDA Project 2032-51530-025-00D (J.W.N).Author conflict of interest: S.M.D. receives research support to his institution from CytoVAS and RenalytixA. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS-Vascular Science policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

Supplementary information

Data that were used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (S.M.D.). Code to perform analyses in this manuscript are available from the authors upon request (S.M.D.). Supplementary methods attached describe the metabolomics methodology in more detail.

Appendix

References

- 1.Fowkes F.G., Rudan D., Rudan I., Aboyans V., Denenberg J.O., McDermott M.M., et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiatt W.R. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1608–1621. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart K.J., Hiatt W.R., Regensteiner J.G., Hirsch A.T. Exercise training for claudication. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1941–1951. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott M.M., Liu K., Ferrucci L., Criqui M.H., Greenland P., Guralnik J.M., et al. Physical performance in peripheral arterial disease: a slower rate of decline in patients who walk more. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:10–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olin J.W., White C.J., Armstrong E.J., Kadian-Dodov D., Hiatt W.R. Peripheral artery disease: evolving role of exercise, medical therapy, and endovascular options. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1338–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy T.P., Cutlip D.E., Regensteiner J.G., Mohler E.R., Cohen D.J., Reynolds M.R., et al. Supervised exercise, stent revascularization, or medical therapy for claudication due to aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: the CLEVER study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:999–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerhard-Herman M.D., Gornik H.L., Barrett C., Barshes N.R., Corriere M.A., Drachman D.E., et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: executive summary. Vasc Med. 2017;22:NP1–NP43. doi: 10.1177/1358863X17701592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hackam D.G., Goodman S.G., Anand S.S. Management of risk in peripheral artery disease: recent therapeutic advances. Am Heart J. 2005;150:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen O.A., Lassen N.A. Effect of daily muscular exercise in patients with intermittent claudication. Lancet. 1966;2:1093–1096. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creasy T.S., McMillan P.J., Fletcher E.W., Collin J., Morris P.J. Is percutaneous transluminal angioplasty better than exercise for claudication? Preliminary results from a prospective randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1990;4:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhry F., Spronk S., van der Laan L., Wever J.J., Teijink J.A., Hoffmann W.H., et al. Endovascular revascularization and supervised exercise for peripheral artery disease and intermittent claudication: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1936–1944. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.14851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelin J., Jivegard L., Taft C., Karlsson J., Sullivan M., Dahllof A.G., et al. Treatment efficacy of intermittent claudication by surgical intervention, supervised physical exercise training compared to no treatment in unselected randomised patients I: one year results of functional and physiological improvements. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;22:107–113. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenhalgh R.M., Belch J.J., Brown L.C., Gaines P.A., Gao L., Reise J.A., et al. Mimic Trial, P The adjuvant benefit of angioplasty in patients with mild to moderate intermittent claudication (MIMIC) managed by supervised exercise, smoking cessation advice and best medical therapy: results from two randomised trials for stenotic femoropopliteal and. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:680–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundgren F., Dahllof A.G., Lundholm K., Schersten T., Volkmann R. Intermittent claudication--surgical reconstruction or physical training? A prospective randomized trial of treatment efficiency. Ann Surg. 1989;209:346–355. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198903000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazari F.A., Gulati S., Rahman M.N., Lee H.L., Mehta T.A., McCollum P.T., et al. Early outcomes from a randomized, controlled trial of supervised exercise, angioplasty, and combined therapy in intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazari F.A., Khan J.A., Carradice D., Samuel N., Abdul Rahman M.N., Gulati S., et al. Randomized clinical trial of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, supervised exercise and combined treatment for intermittent claudication due to femoropopliteal arterial disease. Br J Surg. 2012;99:39–48. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy T.P., Cutlip D.E., Regensteiner J.G., Mohler E.R., Cohen D.J., Reynolds M.R., et al. Investigators, C. S. Supervised exercise versus primary stenting for claudication resulting from aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: six-month outcomes from the claudication: exercise versus endoluminal revascularization (CLEVER) study. Circulation. 2012;125:130–139. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.075770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkins J.M., Collin J., Creasy T.S., Fletcher E.W., Morris P.J. Exercise training versus angioplasty for stable claudication. Long and medium term results of a prospective, randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(96)80171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spronk S., White J.V., Ryjewski C., Rosenblum J., Bosch J.L., Hunink M.G. Invasive treatment of claudication is indicated for patients unable to adequately ambulate during cardiac rehabilitation. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.11.066. discussion 1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dörenkamp S., Mesters I., de Bie R., Teijink J., van Breukelen G. Patient characteristics and comorbidities influence walking distances in symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: a large one-year physiotherapy cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoner M.C., Calligaro K.D., Chaer R.A., Dietzek A.M., Farber A., Guzman R.J., et al. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for endovascular treatment of chronic lower extremity peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64:e1–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.03.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barriocanal A.M., López A., Monreal M., Montané E. Quality assessment of peripheral artery disease clinical guidelines. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDermott M.M. Lower extremity manifestations of peripheral artery disease: the pathophysiologic and functional implications of leg ischemia. Circ Res. 2015;116:1540–1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brendle D.C., Joseph L.J., Corretti M.C., Gardner A.W., Katzel L.I. Effects of exercise rehabilitation on endothelial reactivity in older patients with peripheral arterial disease. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:324–329. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ernst E.E., Matrai A. Intermittent claudication, exercise, and blood rheology. Circulation. 1987;76:1110–1114. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.5.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gustafsson T., Kraus W.E. Exercise-induced angiogenesis-related growth and transcription factors in skeletal muscle, and their modification in muscle pathology. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D75–D89. doi: 10.2741/gustafss. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harwood A.E., Cayton T., Sarvanandan R., Lane R., Chetter I. A review of the potential local mechanisms by which exercise improves functional outcomes in intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;30:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiatt W.R., Regensteiner J.G., Wolfel E.E., Carry M.R., Brass E.P. Effect of exercise training on skeletal muscle histology and metabolism in peripheral arterial disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1996;81:780–788. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parmenter B.J., Dieberg G., Smart N.A. Exercise training for management of peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45:231–244. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0261-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tisi P.V., Shearman C.P. The evidence for exercise-induced inflammation in intermittent claudication: should we encourage patients to stop walking? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;15:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(98)80066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azab S.M., Zamzam A., Syed M.H., Abdin R., Qadura M., Britz-McKibbin P. Serum metabolic signatures of chronic limb-threatening ischemia in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1877. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zagura M., Kals J., Kilk K., Serg M., Kampus P., Eha J., et al. Metabolomic signature of arterial stiffness in male patients with peripheral arterial disease. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:840–846. doi: 10.1038/hr.2015.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker W.B., Li Z., Schenkel S.S., Chandra M., Busch D.R., Englund E.K., et al. Effects of exercise training on calf muscle oxygen extraction and blood flow in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Appl Physiol. 2017;123:1599–1609. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00585.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerhard-Herman M.D., Gornik H.L., Barrett C., Barshes N.R., Corriere M.A., Drachman D.E., et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:e71–e126. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner A.W., Skinner J.S., Cantwell B.W., Smith L.K. Progressive vs single-stage treadmill tests for evaluation of claudication. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23:402–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiehn O. Metabolomics by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry: the combination of targeted and untargeted profiling. Ausubel F.M., et al., editors. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2016;114:30.4.1. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb3004s114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsugawa H., Cajka T., Kind T., Ma Y., Higgins B., Ikeda K., et al. Data independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat Methods. 2015;12:523. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cajka T., Smilowitz J.T., Fiehn O. Validating quantitative untargeted lipidomics across nine Liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry platforms. Anal Chem. 2017;89:12360–12368. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen T.L., Gray I.J., Newman J.W. Plasma and serum oxylipin, endocannabinoid, bile acid, steroid, fatty acid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug quantification in a 96-well plate format. Anal Chim Acta. 2021;1143:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fahy E., Subramaniam S. RefMet: a reference nomenclature for metabolomics. Nat Methods. 2020;17:1173–1174. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng T., Wei C., Yu F., Xu J., Zhou Q., Shi T., et al. Predicting nanotoxicity by an integrated machine learning and metabolomics approach. Environ Pollut. 2020;267:115434. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeFries R.S., Chan J.C.W. Multiple criteria for evaluating machine learning algorithms for land cover classification from satellite data. Remote Sens Environ. 2000;74:503–515. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dias-Audibert F.L., Navarro L.C., de Oliveira D.N., Delafiori J., Melo C.F.O.R., Guerreiro T.M., et al. Combining machine learning and metabolomics to identify weight gain biomarkers. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:6. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Magland J.F., Li C., Langham M.C., Wehrli F.W. Pulse sequence programming in a dynamic visual environment: SequenceTree. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:257–265. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raichlen D.A., Foster A.D., Seillier A., Giuffrida A., Gerdeman G.L. Exercise-induced endocannabinoid signaling is modulated by intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:869–875. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2495-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J., Bhattacharyya S., Hickner R.C., Light A.R., Lambert C.J., Gale B.K., et al. Skeletal muscle interstitial fluid metabolomics at rest and associated with an exercise bout: application in rats and humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019;316:E43–E53. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00156.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saoi M., Percival M., Nemr C., Li A., Gibala M., Britz-Mckibbin P. Characterization of the human skeletal muscle metabolome for elucidating the mechanisms of bicarbonate ingestion on strenuous interval exercise. Anal Chem. 2019;91:4709–4718. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grapov D., Fiehn O., Campbell C., Chandler C.J., Burnett D.J., Souza E.C., et al. Exercise plasma metabolomics and xenometabolomics in obese, sedentary, insulin-resistant women: impact of a fitness and weight loss intervention. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019;317:E999–E1014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00091.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devane W.A., Hanuš L., Breuer A., Pertwee R.G., Stevenson L.A., Griffin G., et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science (1979) 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heyman E., Gamelin F.X., Aucouturier J., Di Marzo V. The role of the endocannabinoid system in skeletal muscle and metabolic adaptations to exercise: potential implications for the treatment of obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13:1110–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cavuoto P., McAinch A.J., Hatzinikolas G., Cameron-Smith D., Wittert G.A. Effects of cannabinoid receptors on skeletal muscle oxidative pathways. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;267:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iannotti F.A., Silvestri C., Mazzarella E., Martella A., Calvigioni D., Piscitelli F., et al. The endocannabinoid 2-AG controls skeletal muscle cell differentiation via CB1 receptor-dependent inhibition of Kv7 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406728111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horvth B., Mukhopadhyay P., Hask G., Pacher P. The endocannabinoid system and plant-derived cannabinoids in diabetes and diabetic complications. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dietrich A., McDaniel W.F. Endocannabinoids and exercise. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:536–541. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.011718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heyman E., Gamelin F.X., Goekint M., Piscitelli F., Roelands B., Leclair E., et al. Intense exercise increases circulating endocannabinoid and BDNF levels in humans-Possible implications for reward and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stone N.L., Millar S.A., Herrod P.J.J., Barrett D.A., Ortori C.A., Mellon V.A., et al. An analysis of endocannabinoid concentrations and mood Following singing and exercise in healthy volunteers. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:269. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao D., Pond A., Watkins B., Gerrard D., Wen Y., Kuang S., et al. Peripheral endocannabinoids regulate skeletal muscle development and maintenance. Eur J Transl Myol. 2010;20:167. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geurts L., Muccioli G.G., Delzenne N.M., Cani P.D. Chronic endocannabinoid system stimulation induces muscle macrophage and lipid accumulation in Type 2 diabetic mice independently of metabolic endotoxaemia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Y.L., Connoley I.P., Wilson C.A., Stock M.J. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 on oxygen consumption and soleus muscle glucose uptake in Lepob/Lep ob mice. Int J Obes. 2005;29:183–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gasperi V., Fezza F., Pasquariello N., Bari M., Oddi S., Finazzi Agrò A., et al. Endocannabinoids in adipocytes during differentiation and their role in glucose uptake. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:219–229. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6445-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pennisi E., Garibaldi M., Antonini G. Lipid myopathies. J Clin Med. 2018;7:472. doi: 10.3390/jcm7120472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brass E.P., Hiatt W.R. Acquired skeletal muscle metabolic myopathy in atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med. 2000;5:55–59. doi: 10.1177/1358836X0000500109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin S.A., Brash A.R., Murphy R.C. The discovery and early structural studies of arachidonic acid. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:1126–1132. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R068072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith G.I., Atherton P., Reeds D.N., Mohammed B.S., Rankin D., Rennie M.J., et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids augment the muscle protein anabolic response to hyperinsulinaemia-hyperaminoacidaemia in healthy young and middle-aged men and women. Clin Sci. 2011;121:267–278. doi: 10.1042/CS20100597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nelson J.R., Raskin S. The eicosapentaenoic acid:arachidonic acid ratio and its clinical utility in cardiovascular disease. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:268–277. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1607414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bäck M., Yurdagul A., Tabas I., Öörni K., Kovanen P.T. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:389–406. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Imig J.D., Hammock B.D. Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:794–805. doi: 10.1038/nrd2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sonnweber T., Pizzini A., Nairz M., Weiss G., Tancevski I. Arachidonic acid metabolites in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3285. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brevetti G., Giugliano G., Brevetti L., Hiatt W.R. Inflammation in peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122:1862–1875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.918417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Signorelli S.S., Valerio F., Malaponte G. Inflammation and peripheral arterial disease: the value of circulating biomarkers (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:777–783. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nylænde M., Kroese A., Stranden E., Morken B., Sandbæk G., Lindahl A.K., et al. Markers of vascular inflammation are associated with the extent of atherosclerosis assessed as angiographic score and treadmill walking distances in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Vasc Med. 2006;11:21–28. doi: 10.1191/1358863x06vm662oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.