Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is underused in the southern United States (US), a region with high HIV incidence. Clinical decision support (CDS) tools could increase PrEP prescriptions. We explored barriers to PrEP delivery and views of CDS tools to identify refinements for implementation strategies for PrEP prescribing and PrEP CDS tools. We conducted focus groups with health care providers from two federally qualified health centers in Alabama and analyzed the results using rapid qualitative methods. Barriers to PrEP included providers’ lack of training in PrEP, competing priorities and time constraints during clinical visits, concerns about side effects, and intensive workload. We identified refinements to the planned implementation strategies to address the barriers, including training all clinic staff in PrEP and having CDS PrEP alerts in electronic health records sent to all staff. Development and deployment of CDS tools in collaboration with providers has potential to increase PrEP prescribing in high-priority jurisdictions.

Keywords: implementation strategies, pre-Exposure prophylaxis, providers, clinical decision support system

Background

Despite comprising one third of the US population, the South accounts for nearly half of all new HIV diagnoses, with the highest infection rates occurring among Black residents.1,2 With nearly 700 new HIV diagnoses each year and more than 10% of new diagnoses in 2016–2017 in non-urban areas,3 Alabama is one of seven states that have been designated a high-priority jurisdiction by the federal Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative.4 Although only 26% of Alabama's population is Black, 67% of newly diagnosed HIV cases are Black, with adolescents and young Black men who have sex with men (MSM) accounting for most of the new infections.5 Despite evidence that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is up to 99% effective for preventing HIV,6,7 PrEP use is lowest in the South and, of the estimated 11,421 Alabamians with PrEP indications, only 1513 (13%) received a PrEP prescription in 2018.8–15 There are large racial and ethnic disparities in PrEP prescription in Alabama, as almost two-thirds of people prescribed PrEP are White.14,16 The goal of the Alabama EHE Plan is to achieve 50% coverage of PrEP by 2025, and achieving that goal will require novel and more effective implementation strategies to increase equitable PrEP prescribing.

Providers at community health centers care for populations with high rates of new HIV infections and are well-positioned for disseminating PrEP in the South.17 However, many Southern providers do not routinely prescribe PrEP, in part because of lack of training in identifying clients who are at increased risk of HIV or because of an inaccurate belief that few of their clients have indications for PrEP.18 Prediction models using electronic health record (EHR) data can identify clients who are at increased risk of HIV and thus likely to benefit from PrEP.19,20 These models can be integrated into EHR-based clinical decision support (CDS) tools to prompt PrEP discussions and prescribing with the clients most likely to benefit from PrEP use.

We initiated a project in 2019 to develop an EHR-based CDS tool utilizing an HIV prediction model to improve PrEP delivery at community health centers in Alabama. Integration of an HIV prediction model into routine clinical practice can be optimized by employing implementation strategies,21,22 which are methods and techniques for enhancing adoption, implementation, and sustainability of evidence-based clinical programs, practices, or policies.23 By testing implementation strategies, researchers can generate evidence about the effectiveness of specific strategies.21–23 Our team previously identified three implementation strategies for PrEP and PrEP CDS tools, which consisted of eliciting stakeholders’ perspectives on PrEP implementation, training providers on the CDS system, and implementing the PrEP CDS system. The objectives of this study were to identify barriers and facilitators for PrEP prescribing and implementation of the CDS system and then use the findings to identify refinements for the PrEP implementation strategies. Addressing barriers to PrEP and the CDS tool identified by local partners may improve the success of CDS tool implementation, which could in turn improve PrEP delivery.24

Methods

Ethical Review

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board (#300004577-009). As focus groups were conducted virtually and with clinic staff, participants reviewed an informed consent sheet and provided oral consent to participate.

Study Setting

We recruited federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in Alabama that offer primary care services in underserved areas. These centers provide HIV prevention services, including PrEP prescribing, and use an EHR platform that can integrate electronic CDS tools. Three FQHCs were approached and two agreed to participate in this study. Both participating FQHCs serve urban residents, as well as individuals in the surrounding suburban and rural areas, with over 80% of their clients at or below the Federal poverty line and 51–58% of their clients identifying as African American. Additional characteristics of the two clinics are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Sampling and Recruitment

With the support of clinic administrators, we recruited a sample of professional clinic staff tasked with supporting PrEP delivery at each clinic. Clinic administrators created a list of clinic staff members who participate in the PrEP delivery process. Two members of the study team (AR and CO) then sent email messages to all individuals on the list with information about the purpose of the study and an invitation to participate in focus group discussions about PrEP. Next, clinic administrators coordinated convenient times for the focus groups for clinic staff interested in participating.

Data Collection

Focus groups are well suited for identifying a range of views and community norms on PrEP prescription and implementation strategies such as CDS tools to increase PrEP use.25 We developed a semi-structured focus group guide to elicit information about provision of PrEP at the participants’ facility including barriers and facilitators to PrEP conversations and prescriptions, opinions about the use of CDS tools to increase PrEP delivery, additional support needs to increase PrEP prescriptions, and current general EHR alert systems and suggestions for improvement. We also elicited information about providers’ awareness and experience with prescribing PrEP. Participants were sent a link to a brief survey of demographics and clinical experience with HIV and PrEP prior to the focus group. Focus groups were co-facilitated by two investigators (AR and CO), one a physician-scientist with expertise in HIV and PrEP, and the other a qualitative researcher. Focus groups were conducted on Zoom Video to maintain social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Each focus group discussion lasted approximately two hours and was audio-recorded. A professional transcription company produced verbatim transcripts and de-identified the textual data. All transcripts were quality checked by the focus group discussion facilitators to ensure accuracy.

Data Analysis

Rapid qualitative analysis was used to ensure provision of results in a short timeframe, while maintaining scientific rigor. Rapid qualitative analytic methods used in implementation research studies have been found to reduce the time required for analysis and to produce valid findings.26 Team members (DLH, CS, ECR, AR) reviewed the focus group guide and developed a standard template for summarizing transcripts, which included headings for all topics covered in the focus group guide and a section to capture unanticipated themes emerging in the data. Next, two team members (DLH and CS) reviewed the transcripts and developed transcript summaries using the standard template (see Supplementary file 2). These summaries were then discussed with other team members (ECR and AR) to ensure all issues in the data were well described and refined as needed. Following team consensus, the summaries were finalized. Next, a matrix was developed in Excel that included a column for each of the topic headings in the summary template and a row for data from each focus group. The matrix was then populated with the information contained in the summaries. Two team members (DLH and CS) then closely read the information in the matrix and synthesized information on each topic, noting similarities and differences in the barriers and facilitators mentioned across sites. Throughout the data analysis process, team members held weekly meetings to discuss results, ensuring findings were strongly grounded in the data and actionable. Physicians and co-authors on the study team (DH, DK, AR, CO), some of whom work locally in Alabama, reviewed, and provided feedback on the summaries to assist with interpretation of the data.

Results

Of 16 staff invited to participate in the study from the two clinics, 12 participated in the focus groups. We conducted two focus groups, one at each clinic. The 11 participants who completed the brief survey were ages 33 to 59, and five identified as Black/African American, one as Native American/Alaskan Native, four as White and one as other race. Participants included nurses (n = 2), nurse practitioners (n = 3), physicians (n = 4), and social workers (n = 2). Six participants reported being very confident of their ability to identify PrEP candidates and the other participants reported being somewhat or a little confident of their ability to identify PrEP candidates. Of the six physicians and nurse practitioners who responded, five were somewhat or very confident of their ability to prescribe PrEP, and the other, who had not previously prescribed PrEP, was a little confident.

Barriers and Facilitators to PrEP Delivery

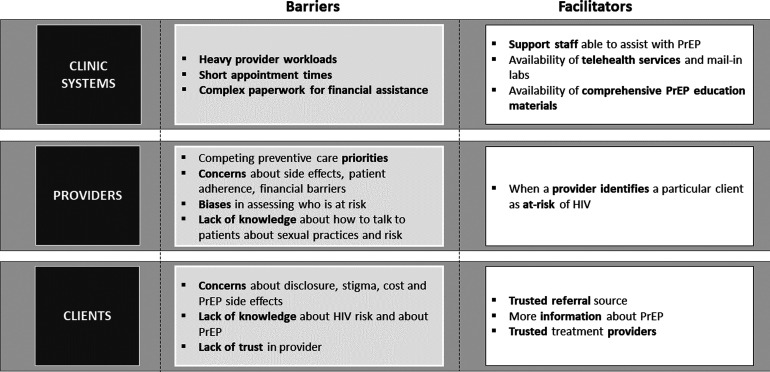

Participants identified multiple barriers and facilitators to PrEP conversations and prescriptions across the clinic, provider, and client levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Provider Perspectives on Barriers and Facilitators for PrEP Conversations and Prescriptions. Barriers and Facilitators for PrEP conversations and prescriptions are identified at the clinic, provider and client levels.

Clinic-Level Barriers and Facilitators

Participants identified heavy workloads, with multiple required quality measures and brief, 15-min appointment durations as critical barriers to PrEP discussions. A lack of support staff to assist with paperwork for financial assistance for PrEP was an additional barrier (see Table 1). Support staff such as nurses and medical assistants were viewed as playing an important role at multiple stages in the PrEP prescribing process, including communicating with clients about HIV risk and assisting clients to complete required steps for obtaining medications. Participants thought that telehealth and remote lab services could make PrEP delivery more convenient and private for clients. Participants suggested that systematic dissemination of PrEP educational materials tailored to potential PrEP clients, those newly initiating PrEP, and other clinic clients could strengthen PrEP delivery and enhance PrEP acceptance more broadly.

Table 1.

Provider and Clinic Level Barriers and Facilitators to PrEP Initiation.

| Level | Barriers | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Provider | Other care priorities | * “[S]ome of our more high risk populations often just have what feels like a more pressing issue. If your IV drug users are actively withdrawing or they’re actively high or they’re emotionally unstable—which we sometimes see with our transgender populations as well—you feel like you need to address this emergent thing sitting in front of you and then the idea of PrEP gets pushed to the background because it's not something that's urgent.” * “[W]hen that patient got to me, in addition to initiating the PrEP, his blood pressure was out of control and, we need to focus on your blood pressure. We need to do all these labs to make sure that it's safe for us to even initiate the PrEP and all this, that, and the other, so in addition to just initiating PrEP, I felt like I took over the role of his PCP [primary care provider]. They already treated him for the syphilis and so I’m requesting records from the PCP to try to get up-to-date, try to find out what medical problems do you have? What all are you on?” * “From what I see, it doesn’t matter how many reminders you have if the physician or nurse practitioner, whoever, doesn’t think it's important, they’re not gonna do anything about it. They’re gonna ignore it. If it's not something they’re comfortable with, they’re not gonna do it.” * “If someone's in with just their blood pressure, actually asking them about their sexual practices and who they’re having sex with and whether or not they’re protected and whether or not they’re at risk is not somethin’ that I necessarily think to do.” |

|

Concerns • Side effects of PrEP • Patient adherence • Financial barriers |

* “It's not without side effects…. —it's just not water or whatever and so I do still have a barrier in my own mind.” * “I think getting patients to take any medication sometimes is a challenge, either through they forget or perceived side effects and so sometimes that can be a real challenge. I personally have a handful of patients that forget to take their blood pressure medication and then end up in the hospital” * “I had one young man, he was on his parents’ insurance…. He was concerned about them [his parents] knowing and so he refused and did not return for follow-up” * “I had a patient that had bipolar disorder and some high-risk sexual behavior and polysubstance abuse and so definitely needed it [PrEP]. I really had a hard time getting his insurance to cover it.… I had to make a lot of phone calls and stuff just to get it covered and it was difficult enough that the patient ended up stopped taking it….” |

|

| Biases in assessing who is at risk | * “[I]t's like a personal blind spot in the sense that I don’t see that risk the same way [in cisgender women] that I see other populations. I’m not having that conversation because I’m much more concerned about unplanned pregnancy or other issues that I know to be an issue with that, with that specific population. | |

| Lack of knowledge about how to talk to patients about sexual practices and risk | * “Transgender, I don’t know—I haven’t—that one feels harder ‘cause of the stigma… I think it's also just more awkward to step into their sexual history as well for some other reason for me.” | |

| Clinic | Heavy provider workload | * “I just don’t see it happening in any scale as an add-on to what we’re already doing in those visits because we have so much to do now, especially with all the quality measures at an FQHC. For us in particular, we have so many things we have to get accomplished and check off and do in a visit. With 15 min slots, it's just not doable.” |

| Short appointment times | * “I think that just like with anything, drug use or any stigmatized societal issue, I think that stigma plays a big role in a patient's not talking about some of these things. I think someone mentioned having the 15 min appointment slot is problematic because you can’t dig into some of these things I guess in that time period.” | |

| Clinic | Paperwork for financial assistance | * “I had a patient that had bipolar disorder and some high-risk sexual behavior and polysubstance abuse and so definitely needed it [PrEP]. I really had a hard time getting his insurance to cover it. He was on a Medicare—I forget which one—but they gave me a lot of pushback. I had to make a lot of phone calls and stuff just to get it covered.” |

| Provider | Provider confidence of client risk | * “I think with certain patient populations of it being just big time offering that and just being able to convince them really from my heart, like, 'No. You need to do this.' Where there's [a] couple discordant or MSM, I really feel passionate about that….” |

| Clinic | Support staff able to provide assistance with PrEP | * “All of our social work case management staff are trained to help with patient assistance with our providers that identify patients who need PrEP, so that's somethin’ we have in the arsenal, is to be able to assist the providers and the patient obtaining the medication for those who are under or uninsured.” |

| Provider use of tele-health & mail-in labs | * “[I] have a telemedicine job that I do PrEP in other parts of the country. We tend to have a lot of good follow-up because you don’t have to go in. It's all mailed to you. You mail it in, so we have a lot of compliance.” | |

| Comprehensive patient education materials about PrEP | * “I think having a large stack of PrEP handouts would be really helpful. I would probably just get it off the CDC or somethin’ website and give it to ‘em if I was—need to give the handout in the clinic, but we don’t have a standardized thing in that that I know of.” |

Provider-Level Barriers and Facilitators

Participants identified multiple barriers that influenced when and how providers offer PrEP, including competing health care priorities for their patients, concerns about side effects of PrEP, patients’ medication adherence and financial barriers, providers’ biases in assessing HIV risk (eg focusing more on sexual and gender minorities than other populations), and their insufficient knowledge or skill to have effective conversations about sexual behaviors and HIV risk (Table 1). Providers see clients with complex or emergent needs and may not prioritize PrEP during such encounters. Providers’ priorities also influenced how they respond to clinical prompts in the EHR and whether they address sexual health and HIV risk in appointments focused on other medical issues. Participants were concerned about clients being able to take PrEP daily without missing doses, particularly given their experience with clients not remembering to take daily medications for conditions such as hypertension. Financial concerns raised included the complexity of paperwork for reimbursement for PrEP care and the perceived difficulty of getting coverage for PrEP medications particularly from Medicaid. Participants reported lacking skills to accurately assess clients’ HIV risk and acknowledged their own biases in identifying clients at risk of HIV, such as not seeing cisgender women as a group likely to benefit from PrEP. Participants noted that talking about sexual behaviors and HIV can be uncomfortable for both providers and clients, making it difficult to ascertain information necessary to identify persons who are likely to benefit from PrEP use. Having conversations about sexual behaviors with transgender clients was viewed as particularly challenging because providers lack training in transgender health care. Participants noted that providers who are confident that a particular client is at increased risk of HIV can communicate “from the heart” about the importance of PrEP, making their conversation more effective.

Client-Level Barriers and Facilitators

Based on their experiences in clinical practice, providers believed that client-level barriers included clients’ concerns about disclosure and stigma surrounding HIV risk and PrEP use, potential side effects of PrEP, costs, lack of community knowledge about PrEP, and mistrust of providers, particularly in discussing sexual behaviors (see Figure 1, Table 2). Perceived facilitators included being referred to PrEP providers by a trusted friend and having trust in PrEP providers and sources of information about PrEP.

Table 2.

Provider-Identified Client Level Barriers and Facilitators to PrEP Initiation.

| Barriers | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

|

Concerns • Disclosure • Stigma • Side effects • Costs |

* “Patients who live in the area, they would rather go to Mobile for care and some of the patients from Mobile who’d rather come to Mount Vernon for care for fear of someone knowing them….” * “I think one of our bigger problems is to get the stigma off of providers who are looking at this the way they looked at birth control when it came out. ‘Well, if I give it to ‘em they’re gonna have sex.’ Well, they’re gonna do it anyway.” * “What I’m hearing from [people living with HIV] is that their friends are afraid to take PrEP because of the side effects.” * “two of the three that I have on PrEP are young gentlemen over 26 that are no longer on their parents’ insurance. Lack of insurance and getting them to complete the necessary paperwork for patient assistance has been a barrier just to get them the medicine because they can’t afford it.” |

|

Lack of knowledge •about PrEP • about risks |

* “The other barrier I have is simply people don’t know. They don’t know…. We need to put fliers in barbershops, nail shops, hair shops. We need to put it where our people are. * “[T]hey just don’t think they need it. They don’t see it from the perspective I’m seein’. I’m like, 'If you’re worried that your partner is not being faithful to you, then you need to do something different. Either A, you need to wear a condom every time or B, you need to get on PrEP so that you have prevention for you.'” * “It would help patients with HIV, just maybe help them have those conversations with their partners…. I’m discussing it with my HIV positive patient. Their partner's not part of the visit, so I’m just wondering how much of the information that I’m giving them is bein’ transferred back, so I think a handout would maybe help them have those conversations as well.” |

| Lack of trust in provider | * “[I]t sounds like sometimes they don’t trust the person…—their PCP [primary care provider]. They don’t wanna have that conversation. They don’t wanna talk to their PCP about what they’re doing.” |

| Facilitators | Illustrative quotes |

| Trusted referral source (eg friends, peers, etc) | * “I have a lot of patients who have now started telling friends to come and get it, so I’ve seen an increase in uptake.” |

| More information about PrEP | * “Something educational that could be on the wall that could—that's colorful and draws people's attention that might spawn them to read it….” |

| Trusted treatment providers | * “Sometimes if you have a good RN who's okay with talkin’ about it [sexual activity], that's something that sometimes a provider can be like, 'Hey, can you just go in and smooth something over and see what's goin’ on?' … Sometimes they can do that and get more information….” |

Provider Perspectives on CDS Tool for Enhancing PrEP Delivery

Acceptability

Participants expressed their enthusiasm for a CDS tool for PrEP and willingness to implement it. They asserted that a CDS tool could help identify more clients who could benefit from PrEP and enable them to more successfully prioritize and integrate PrEP prescription into their routine practice: “[H]aving an automated process like that makes it—you get the muscle memory. You get into the habit of doing something and then it becomes something routine for you.”

Feedback and Suggestions

Providers focused on suggestions for improving the CDS tools, but also noted as a challenge, that when a provider is not comfortable talking about sexual health and HIV risk or does not think PrEP is a priority for a client, the provider may ignore an alert from a CDS tool to discuss PrEP, which would limit the tool's impact. When asked about suggestions for the design of a CDS tool, participants highlighted the importance of alerts having high specificity in identifying persons who are likely to benefit from using PrEP, as they were concerned that if too many alerts were triggered, providers would experience alert fatigue and might not respond to the alerts. Participants also suggested that clients with the greatest estimated HIV risk might merit more intensive flagging in the CDS tool. Participants identified multiple resources that could be included to facilitate PrEP prescribing, including guidance or algorithms for choosing among PrEP formulations, implementing the recommended follow up schedule, and identifying billing codes to ensure insurance coverage (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Provider Recommendations for Clinical Decision Support (CDS) System.

| Recommendations | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Keep alerts specific to avoid 'alert fatigue' | "[Y]ou don’t want too many because then you just get overloaded…" |

| Use flags in the electronic medical records to highlight patient risk and HIV testing status | “A hard stop for somethin’ like that where you say, ‘Hey, this isn’t a little thing. This is something big,’… —if somebody checks off in a box, ‘My partner has HIV,’ that would be a hard stop. Hey, we really need to talk to this person about PrEP or, ‘Hey, I have multiple sex partners,’ or whatever…. [T]hat would still be one of those ones that you say, ‘Hey, this is somethin’ we need to address to make sure we don’t keep having another issue.’” |

| Include guidance for providers on drug selection and follow up schedule | “[T]hings that would be good would be a simple algorithm of who gets what because I do have - people get confused on who gets Descovy, who gets Truvada. A simple algorithm of when they come in, how often and have that where somebody schedules….” |

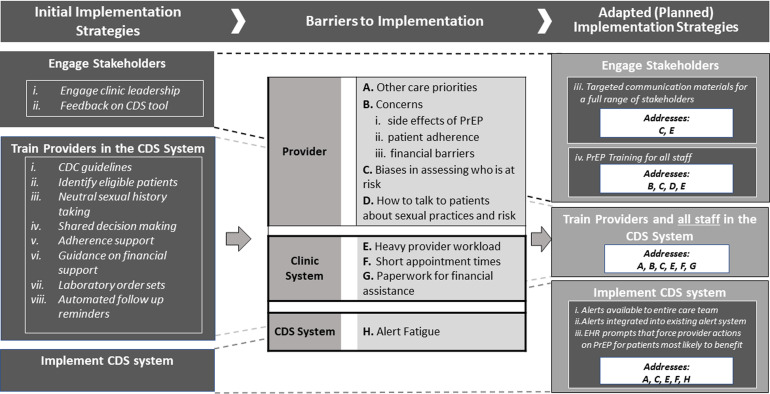

Refining Implementation Strategies for PrEP Initiation

We identified ways to refine our three planned implementation strategies – engaging stakeholders, training providers in the PrEP CDS tool, and implementing the tool - to address the barriers to use of PrEP and the CDS tool that emerged from our focus group discussions (see Figure 2). Promising refinements include training all clinic staff in PrEP, making alerts available to the entire care team as way to offload providers and increase opportunities for PrEP conversations with clients, and creating educational materials about PrEP that are tailored for multiple populations to improve inclusivity. While some of the perceived client-level barriers can be addressed at least in part by the refined strategies, namely educational materials to address concerns about side effects, clients’ lack of knowledge and possibly concerns about stigma, and engagement of clinic staff to help navigate costs and reimbursement, other barriers, such as concerns about disclosure and access to health care without parental knowledge for young adults, may require different strategies to address.

Figure 2.

Refining strategies to integrate provider perspectives. Initial implementation strategies are aligned with the barriers to implementation of both PrEP prescribing and a PrEP CDS system, and adaptations to the initial implementation strategies are identified.

Engaging Stakeholders

Prior to conducting the formative work reported here, the research team had identified engaging with clinic leadership, providers, and staff to obtain feedback on the PrEP CDS tool as an important implementation strategy. Participants in the focus groups also highlighted the importance of engaging with additional stakeholders, by having educational materials available for the general public, potential PrEP clients, and clients newly initiating PrEP. Providing tailored communication materials to clients could allow them to be more informed about PrEP and potentially assess their own HIV risk, side-stepping provider biases in client risk assessment (see Figure 2, barrier C) and reducing providers’ time demands for addressing PrEP (barrier E). Providing PrEP training for all clinic staff could encourage all staff to consider who might benefit from a discussion about PrEP (barrier C), allow staff who are most comfortable talking with clients about sexual behaviors and HIV to do so (barrier D), draw on many staff members’ time with clients to increase capacity and opportunities to talk with clients about PrEP (barriers E and F), and strengthen preparedness of support staff to provide assistance with financial paperwork (barrier G).

Training Providers on a CDS Tool

The team had identified provider training as an important implementation strategy for a PrEP CDS tool. Explicitly including all staff in a CDS tool training would address a number of barriers, including providers’ need to navigate competing health priorities for individual clients and their concerns and biases for PrEP (barriers A-C) as well as their ability to have conversations about sexual risk (barrier D). Trainings will need to directly address providers’ concerns about side effects and medication adherence, as well as providers’ priorities and ability to effectively talk with clients about sexual behaviors and risk. As the participants noted, the practitioners most able to have effective conversations with clients are those who are passionate about safe sex and comfortable discussing PrEP: “I think it [role of talking to clients about HIV risk and PrEP] needs to go to whoever has the passion for this [talking to clients about HIV risk and PrEP] and wants—and isn’t scared to do it because clients know if you’re not comfortable and they close up.” The importance of client autonomy can also be incorporated into the training. As one participant noted, “one thing I want you to remember or to take away from this is that although we know that PrEP is an important medication to help, that everyone, all of our—the patients are not going to get on board to take it, even if we put straight facts 1, 2, 3, A, B, C. It's a personal choice. As professionals, we have to respect that, even though the facts may say that you really need to do this. Just know that it's not gonna always work out the way planned and we just have to rock ‘n roll with it.”

Implement a PrEP CDS Tool

Our team had identified deployment of a CDS tool as a key implementation strategy for enhancing PrEP uptake in Alabama. Participant input suggested integrating the alerts into the EHR platform and making the alerts available to the entire health care team. This could highlight PrEP as a priority for particular visits (addressing barrier A) and mitigate the negative effects of providers’ biases in assessing who is likely to benefit from PrEP use (barrier C). In addition, drawing the entire care team into the response to alerts, in combination with the PrEP and CDS trainings for all staff, could expand available time for discussing PrEP and HIV with particular clients, as mentioned above (barriers E and F). Building a high specificity CDS tool to ensure the alert identifies a manageable number of clients as potentially having indications for PrEP use could address provider concerns about too many alerts (barrier H).

Discussion

Through focus groups with providers in Alabama and rapid qualitative analysis, we identified perceived barriers and facilitators to PrEP prescribing and ways to implement electronic PrEP CDS tools to address barriers. We learned that major barriers to PrEP use may exist at multiple levels of the health care system, including for clinics (eg, intensive provider workloads), providers (eg, concerns about medication side effects, suboptimal adherence, and financial barriers, and a lack of training in HIV risk assessments), and clients (eg, medical mistrust, lack of knowledge about PrEP, and concerns about side effects, stigma, and costs). We also identified facilitators for PrEP use at these multiple levels, including the engagement of diverse clinic staff in PrEP provision, helping providers to feel confident about which clients are at greatest risk for HIV, and clients having trusted referral sources, educational materials, and providers for PrEP. In light of these barriers and facilitators, we identified ways to refine the planned implementation strategies for the PrEP CDS tool, such as embedding tailored educational materials about PrEP for diverse stakeholders and engaging the full range of clinical staff in the use of CDS for PrEP. As this is one of the first studies to assess providers’ perspectives on ways to improve PrEP and PrEP decision support tools in FQHCs in Alabama, this work can lay the foundation for the design, implementation, and evaluation of programs that integrate electronic decision support tools to improve HIV prevention in FQHCs in this state.

Our findings are consistent with three recent studies addressing barriers to PrEP access, including a literature review from 202027 and others from 2021 based on interviews with primary care providers across the United States28 and with women experiencing intimate partner violence and their providers in the Northeast.29 Specifically, all the barriers to PrEP identified in the current study were identified in at least one of the other studies, with some, such as concerns about side effects and adherence and provider biases or stigma about who is at risk for HIV, being identified by all three studies.27–29 Barriers identified in one or more of the other studies and not in the present study included disagreements over whether primary care providers or specialists should take the lead in PrEP prescribing,27,28 which may be important to consider when training providers in Alabama in order to maximize provider motivation and engagement in PrEP regardless of their specialties.

In this study, participants identified barriers they believed are faced by their clients, including clients’ concerns about disclosure of sexual risk factors, stigma and side effects for PrEP, lack of knowledge about HIV and PrEP, and lack of trust in providers. There was substantial overlap with barriers that current and potential PrEP clients reported in a recent qualitative study also conducted in Birmingham, Alabama.30 In that study client barriers also included lack of PrEP awareness, sexuality-related stigma, client time and resource constraints, and concerns about the adequacy and technical quality of PrEP services.30 The similarities of barriers identified in this prior study and our own work suggest that the client-level barriers and facilitators participants in our study articulated are likely to reflect clients’ experiences well and therefore are useful to consider when refining our PrEP implementation strategies.

Participants’ recommendations to train the entire clinic team and to deploy tailored educational interventions for a full range of stakeholders, including practitioners and clients, are similar to the recommendations that emerged from a study of clinical and non-clinical PrEP providers such as clinicians, counselors, and support staff who emphasized the importance of normalizing and universalizing PrEP education and services throughout clinics.31 Task shifting to non-prescribers in the care team was emphasized in a study of primary care providers’ attitudes about PrEP that also identified the importance of integrating PrEP procedures into clinical workflows.28 Our work therefore reinforces the importance of focusing PrEP implementation strategies on a full range of stakeholders, which aligns with best-practices in implementation science methods that have been emphasized in the Federal Plan to End the HIV Epidemic.32

Future Research

Because the focus of the current study was on PrEP prescribing in the context of a PrEP CDS tool, the focus groups elicited information about the PrEP initiation process and use of a PrEP CDS tool. As such, there was limited discussion about barriers and facilitators to longer-term PrEP adherence and persistence, which are critical to prevention effectiveness, although participants did identify their concerns about clients’ adherence to PrEP as one of the barriers to discussing and prescribing PrEP. Future work could shed light on ways to help providers to support PrEP adherence, including ways to use CDS tools to accomplish this, such as through automated scheduling and reminders for refills and follow-up visits and electronic dissemination of patient-oriented materials on the benefits of persisting with PrEP, which are practical and realistic solutions that have been used to support health care engagement in other areas of medicine

Limitations

Our study design had several limitations. The focus group guide was developed and used for previous research on a PrEP CDS tool,33 and was revised by the study team that included local experts. Although the guide was not pilot tested with the intended population, we found that the guide worked well for promoting discussion and eliciting the information needed. Focus groups were conducted at two FQHCs that serve communities in which PrEP is underused, which may help explain why participants expressed interest in using a CDS tool for PrEP. Therefore, the findings may not be transferable to clinics where PrEP use is high. The focus groups were held virtually, and the professional transcription did not include labeling speakers, so comments could not be labeled with any key participant characteristics such as background or confidence in PrEP prescribing.

Strengths

Our study also had multiple strengths. We used a rapid qualitative analysis, an approach that is increasingly used in implementation science research to more rapidly integrate results of formative work to inform the tailoring of evidence-based interventions and implementation strategies.34,35 We found that this approach facilitated generation of timely and relevant findings for successfully moving forward with the next steps of our implementation science project, namely implementation and testing of the refined implementation strategies.26 Additionally, this study was conducted through a partnership between academic researchers and public health authorities and clinics in an EHE priority state, which helped ensure that the research focused on clinically relevant questions that can be used to inform practice in the study setting and potentially additional jurisdictions in Alabama. Finally, we achieved professional diversity in the sample, with prescribing providers and other key clinic staff such as nurses and social workers participating in the focus groups. We were therefore able to capture a range of perspectives to inform the ultimate implementation strategies that will directly impact these stakeholders.

Conclusions

Using rapid qualitative analysis, we efficiently identified providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to PrEP prescribing and implementation of a CDS tool to enhance PrEP use as well as ways to refine our implementation strategies for this tool to improve its use and impact. Potential refinements to the planned implementation strategies include making educational materials about PrEP available for all clinic clients including those who are most likely to benefit from PrEP use, training all clinic staff in PrEP and how to use the PrEP CDS tools, and directing alerts about clients who are likely to benefit from PrEP use to the entire health care team to offload providers and maximize opportunities for PrEP discussions. These refinements are specifically designed to reduce the impacts of barriers such as providers’ and clients’ concerns about PrEP, as well as providers’ biases and clinic workloads, on rates of PrEP prescribing. These results will strengthen the implementation of the PrEP CDS tool and have the potential to increase PrEP discussions and prescribing in a high-priority jurisdiction and to enhance implementation of the PrEP CDS tool in other clinics, which could in turn increase PrEP provision and impact the HIV epidemic.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-jia-10.1177_23259582221144451 for Using Health Care Professionals’ Perspectives to Refine a Clinical Decision Support Implementation Strategy for Increasing the Prescribing of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Alabama by Debbie L. Humphries, Elizabeth C. Rhodes, Christine L. Simon, Victor Wang, Donna Spiegelman, Corilyn Ott, David Hicks, Julia L. Marcus, Doug Krakower and Aadia Rana in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-2-jia-10.1177_23259582221144451 for Using Health Care Professionals’ Perspectives to Refine a Clinical Decision Support Implementation Strategy for Increasing the Prescribing of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Alabama by Debbie L. Humphries, Elizabeth C. Rhodes, Christine L. Simon, Victor Wang, Donna Spiegelman, Corilyn Ott, David Hicks, Julia L. Marcus, Doug Krakower and Aadia Rana in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Acknowledgements

We thank the clinics that supported this project and contributed to recruitment. We also are grateful to the participants in the focus groups who shared their perspectives and suggestions.

Footnotes

Author's Contributions: DK, JLM, DH, AR and DS designed the study and obtained funding, AR and CO developed the data collection guide with feedback from DLH, ECR and CLS; AR and CO collected the qualitative data; DLH, ECR, CLS & AR conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript; VW assisted with analysis and developed figures and tables; all authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Material: The template used to analyze the focus groups is provided as supplemental Table 2; data collection materials and qualitative data generated and analyzed during the study are not publicly available but may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All requests for data should be made to the corresponding author at debbie.humphries@yale.edu.

Consent to Participate: All participants reviewed an informed consent and provided oral consent to participate in the focus group.

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Code availability: Not applicable

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board (#300004577-009). As focus groups were conducted virtually and with clinic staff, participants reviewed an informed consent sheet and provided oral consent to participate.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was a public health-academic partnership funded as part of the 2019 NIH Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) Ending the HIV Epidemic administrative supplement opportunity awarded to Harvard CFAR (P30AI060354). Technical support was provided by the Rigorous, Rapid and Relevant Evidence aDaptation and Implementation (R3EDI) to Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) technical assistance hub funded under NIH AIDS Research Centers (ARC) Ending the HIV Epidemic administrative supplements awarded to the Yale ARC (3P30MH062294-19S1) in 2020 and 2021. National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, (grant number 3P30MH062294-19S1, P30AI060354).

ORCID iDs: Debbie L. Humphries https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5979-3717

Aadia Rana https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1963-528X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Reif S, Pence BW, Hall I, Hu X, Whetten K, Wilson E. HIV Diagnoses, prevalence and outcomes in nine southern states. J Community Health. 2015;40(4):642–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2019. 2021. Contract No.: 05/23/2022.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Ending the HIV Epidemic: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [updated 3/10/2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/endhiv/index.html.

- 4.Abbasi J. Anthony fauci, MD: Working to End HIV/AIDS. JAMA. 2018;320(4):327–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alabama_Department_of_Public_Health. Brief Facts on African Americans and HIV in Alabama. 2019. Available from: https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/hiv/assets/brieffactsonafricanamericansandhiv.pdf.

- 6.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: A cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(1):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karris MY, Beekmann SE, Mehta SR, Anderson CM, Polgreen PM. Are we prepped for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? provider opinions on the real-world use of PrEP in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(5):704–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathi A, Ogbuanu C, Monger M, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection: Healthcare providers’ knowledge, perception, and willingness to adopt future implementation in the southern US. South Med J. 2012;105(4):199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital signs: Estimated percentages and numbers of adults with indications for preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(46):1291–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Highleyman L. PrEP use is rising fast in US, but large racial disparities remain 2016. Available from: http://www.aidsmap.com/PrEP-use-is-rising-fast-in-US-but-large-racial-disparities-remain/page/3065545/.

- 12.Mera R, McCallister S, Palmer B, Mayer G, Magnuson D, Rawlings M. FTC/TDF (Truvada) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States: 2012–2015. Foster City, CA, USA. 2016.

- 13.Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis–to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan PS, Giler RM, Mouhanna F, et al. Trends in the use of oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection, United States, 2012–2017. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prevention CfDCa. HIV prevention to end the HIV epidemic in the United States: ALABAMA 2021.

- 16.Mera R, McCallister S, Palmer B, Mayer G, Magnuson D, Rawlings M. FTC/TDF (Truvada) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States: 2012–2015. Foster City, CA, USA; 2016.

- 17.Shin P, Alvarez C, Sharac J, et al. A profile of community health center patients: implications for policy. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clement ME, Seidelman J, Wu J, et al. An educational initiative in response to identified PrEP prescribing needs among PCPs in the southern US. AIDS Care. 2018;30(5):650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krakower DS, Gruber S, Hsu K, et al. Development and validation of an automated HIV prediction algorithm to identify candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis: A modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(10):e696–e704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Krakower DS, Alexeeff S, Silverberg MJ, Volk JE. Use of electronic health record data and machine learning to identify candidates for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: A modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(10):e688–ee95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hennink MM. Focus group discussions. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the veterans health administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pleuhs B, Quinn KG, Walsh JL, Petroll AE, John SA. Health care provider barriers to HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: A systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(3):111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storholm ED, Ober AJ, Mizel ML, et al. Primary care Providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Informing network-based interventions. AIDS Educ Prev. 2021;33(4):325–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caplon A, Alexander KA, Kershaw T, Willie TC. Assessing provider-, clinic-, and structural-level barriers and recommendations to Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake: A qualitative investigation among women experiencing intimate partner violence, intimate partner violence service providers, and healthcare providers. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(10):3425–3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rice WS, Stringer KL, Sohail M, et al. Accessing Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Perceptions of current and potential PrEP users in Birmingham, alabama. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(11):2966–2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price DM, Unger Z, Wu Y, Meyers K, Golub SA. Clinic-Level strategies for mitigating structural and interpersonal HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis stigma. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2022;36(3):115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Berg P, Powell VE, Wilson IB, Klompas M, Mayer K, Krakower DS. Primary care Providers’ perspectives on using automated HIV risk prediction models to identify potential candidates for Pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(11):3651–3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corneli A, Perry B, Wilson J, et al. Identification of determinants and implementation strategies to increase PrEP uptake among black same gender-loving men in mecklenburg county, north Carolina: The PrEP-MECK study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022;90(S1):S149–SS60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Hart C, Mackson G, Belanger D, et al. HIV And intersectional stigma reduction among organizations providing HIV services in New York city: A mixed-methods implementation science project. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(5):1431–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-jia-10.1177_23259582221144451 for Using Health Care Professionals’ Perspectives to Refine a Clinical Decision Support Implementation Strategy for Increasing the Prescribing of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Alabama by Debbie L. Humphries, Elizabeth C. Rhodes, Christine L. Simon, Victor Wang, Donna Spiegelman, Corilyn Ott, David Hicks, Julia L. Marcus, Doug Krakower and Aadia Rana in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-2-jia-10.1177_23259582221144451 for Using Health Care Professionals’ Perspectives to Refine a Clinical Decision Support Implementation Strategy for Increasing the Prescribing of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Alabama by Debbie L. Humphries, Elizabeth C. Rhodes, Christine L. Simon, Victor Wang, Donna Spiegelman, Corilyn Ott, David Hicks, Julia L. Marcus, Doug Krakower and Aadia Rana in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)