Abstract

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is emerging as a new technology in the healthcare sector. It has been shown to enhance the patient’s experience and satisfaction in various settings. This review aims to give a brief description of the use of VR and establish validity of its applications to improve the patient’s pathway through surgery.

Methods

A literature search was conducted using the PubMed and Embase™ databases to identify fields in which VR technology has been trialled in relation to surgery. The search terms ‘virtual reality’ and ‘surgery’ were employed.

Results

Although benefits relating to VR use have been identified in mental health, obesity management, and physical and cognitive rehabilitation, those in surgery have been less well documented. There are, however, some important but limited benefits reported in managing surgery related stress and improving preoperative patient education as well as VR being an adjunct to some level of postoperative analgesia.

Conclusions

The current applications of VR in relation to surgical care fall into four main categories: preoperative education, supporting mental health, postoperative pain management, and pre and postoperative patient optimisation. Future studies and validation of VR applications should be carried out so the technology can be utilised throughout the entire patient pathway as VR surgical care bundles.

Keywords: Virtual reality, Surgery, Preoperative care, Postoperative recovery

Introduction

An acceleration in digital healthcare translation is underway, fuelled in part more recently by the COVID-19 pandemic, including the broader introduction of virtual reality (VR) technology. VR technology enables users to be fully immersed in a simulated world with interactive visual, auditory and motor environments. It generates superimposed three-dimensional multimedia that can be controlled and displayed through computer, mobile devices or head-mounted displays.1

In 2018, Cipresso et al conducted a network and cluster analysis of the utilisation of VR and augmented reality.2 This showed an increase in the development of VR in many industrial and educational fields with the main peak of research in media and medicine.

VR use has shown enhanced educational properties in medical education (eg anatomy studies, communication, simulation-based decision making and skills acquisition).3 Additionally, VR has played an emerging role in providing patient centred services. It was reported to be a beneficial tool for patient education, improving mental health, controlling postoperative pain, physical therapy and rehabilitation.4-6

Depending on the modality of control and display, VR can be non-immersive or immersive, with more development and research directed towards the latter. Many reports have shown the feasibility and safety of applying immersive VR in patient care with various propositions. The focus of this review is to provide an insight into some aspects of immersive VR and its impacts on a variety of patient centred surgical applications in addition to evaluating where the benefits of VR will be prominent in the surgical space of the future.

Methods

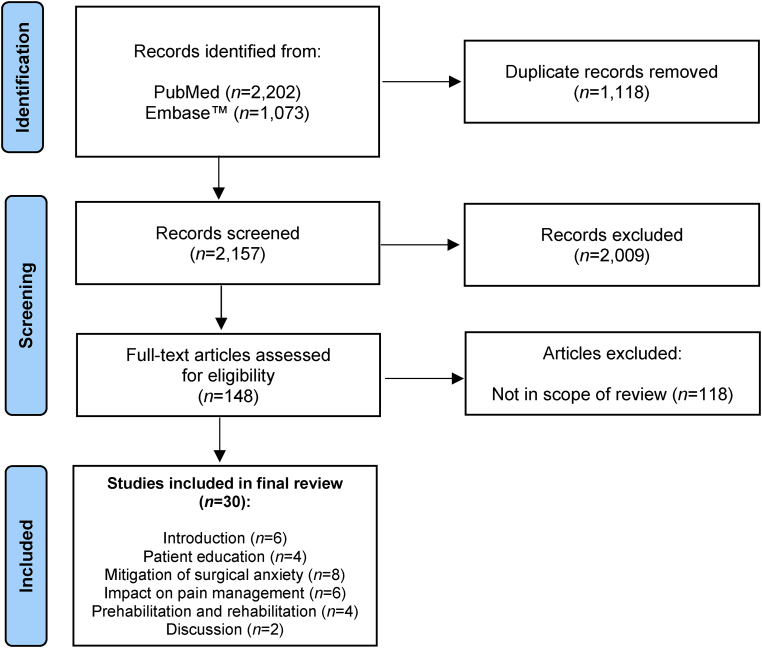

A literature search of papers published between 2010 and June 2021 was conducted using the PubMed and Embase™ databases in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines7 to identify fields in which VR technology has been trialled in relation to patients undergoing surgery. The search terms ‘virtual reality’ and ‘surgery’ were employed. Figure 1 summarises the study selection process. Relevant published reports that explored the use of immersive VR with patient centred applications were included in our review, which was based on a concept of developing a VR ecosystem for surgical patients. This concept aimed to provide patients with VR applications throughout their surgical pathway with the main purpose of easing and improving patient centred surgical care.

Figure 1 .

Flowchart of study selection

Results

Thirty papers were included in our review (Figure 1). On examining the different applications for VR in surgery, four main categories were identified in which patients can utilise this technology throughout the surgical pathway: preoperative education, mitigation of surgical anxiety, impact on pain management, and prehabilitation and rehabilitation applications.

Preoperative education

Patient education has evolved from simple leaflets and text-based information to more advanced VR information.8 Most surgeons and physicians share procedural information and findings with patients using text-based documentations and drawings, which are more focused towards medical documentations.9 These standard approaches can sometimes lead to cognitive overload with mixed messages and poor communications.10

VR can provide enhanced visual and auditory feedback to patients about their conditions. This has been reported to improve health knowledge and aid in decision making through a more informative and interactive model utilising reconstructed images, prepared three-dimensional models or simulated environments, from which patients will potentially have more opportunities to gain deeper insights into the steps of their procedure and the treatment options.11

Favourable results were demonstrated by Pandrangi et al with the use of VR as a preoperative educational tool for patients undergoing aortic surgery for aneurysmal disease; 17 of 19 participants (89%) agreed that VR models of their surgical anatomy were useful, informative and more effective than conventional approaches.12 Similar results were reported for patients receiving radiotherapy for breast, prostate, lung, rectal and endometrial cancer.13,14

Mitigation of surgical anxiety

Anxiety around surgery is related to emotional fear in the preoperative setting, the perioperative journey and recovery.15,16 Excessive preoperative anxiety has been linked to both physical and psychological states. This can result in longer recovery, and an increase in analgesia and anaesthetic requirement, as well as unfavourable emotional and behavioural outcomes.17 Standard interventions for preoperative anxiety can be categorised as either pharmacological or non-pharmacological (eg effective communication/education strategies).18

VR can reduce anxiety in many clinical and surgical settings.19 The rationale for using VR immersive technology is its ability to provide a simulated environment tailored to match specific aspects that cause fear in patients; alternatively, VR can take patients to a relaxing augmented reality that can divert patients’ thoughts from their fear.20 This has already been shown to significantly reduce anxiety, acute and chronic pain, and wound healing times, with favourable outcomes in burns and complex pain issues.21,22

Chan et al examined the utility of a VR headset to reduce anxiety before hysteroscopy in the form of a short video of a relaxing scenario.23 There was a significant reduction in preoperative stress and discomfort levels, and 82% of the patients rated their experience as ‘good’ or ‘excellent’. Similar results have been noted for other gynaecological interventions.24,25 In addition, Haisley et al described using VR in a randomised controlled trial as a tool to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing minimally invasive gastrointestinal surgery.26 Although their results did not reach statistical significance, they acknowledged that their study was underpowered.

Impact on pain management

Preoperatively, VR is used as an information tool for patients to understand their procedure better. This improves their experience and satisfaction, and (in some cases) reduces analgesic requirement by decreasing the level of stress.27 The use of VR as a preoperative tool to reduce pain has not been described frequently in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Some reports have evaluated the application of VR in knee and spine interventions with favourable results in reducing pain intensity and discomfort after surgery.28 These applications could also be tested in abdominal surgery with enhanced recovery protocols.

In patients undergoing colonoscopy with standard sedation, Veldhuijzen et al utilised VR glasses as a distraction tool for ten patients and compared outcomes with a control group of nine patients.29 Their study showed no significant difference between the two groups in terms of pain or discomfort. The VR group reported their experience as ‘pleasant and distracting’.

The utility of VR as pain control after surgery has been described for a variety of minor and major surgical procedures. In a randomised study with 182 patients undergoing haemorrhoidectomy, Ding et al compared the use of VR distraction with standard pain medications during wound dressing and found that patients in the VR distraction group had significantly lower pain scores after 5–20 minutes of wound dressing.30 Another prospective non-controlled study by Mosso-Vázquez et al with 67 patients undergoing cardiac surgery noted a mean decrease in Likert pain ratings following a VR intervention in 88% of patients, with some improvement of physiological parameters in the form of reduced heart rate (37.3%) and respiratory rate (63.6%).31

In addition to looking at patient anxiety, Haisley et al’s study investigated the effects of a relaxing VR environment on patient reported postoperative pain and need for analgesia.26 No significant difference was observed. However, the majority of the VR group stated that they would like to use VR again.

VR has also been explored in various settings to control pain in different medical conditions. A study of 120 patients by Spiegel et al compared the use of VR headsets versus relaxing videos displayed on standard monitors; patients randomised to the VR intervention had significantly lower pain scores although there was no difference between the two groups in opiate usage.32

Prehabilitation and rehabilitation applications

Pre and postoperative physical (p)rehabilitation is regarded as an important step in enhanced recovery programmes as it improves the patient’s response to the stresses of major surgery. It aids postoperative recovery as well as return to normal functional status, nutritional status and cardiovascular function alongside reducing complications.33 Standard preoperative exercise programmes usually involve respiratory, aerobic or resistance training. This can be either unsupervised or supervised.34 With the recent progress in immersive VR-based exercise in a virtual gaming environment, VR has been recognised as a new tool to improve physical activity and health promotion.35 It offers reliable and motivational exercise in an interactive augmented environment that not only encourages body movement but also stimulates the visual and auditory senses.36 This helps patients to adhere to exercise routines with proven psychological benefits.37

Preoperative use of VR exercises has not yet been explored. An attempt by Steffens et al to perform a systematic review in 2020 relating to technology-based preoperative exercise for patients undergoing cancer surgery did not identify any quality studies to provide reliable evidence.38 While many studies have reported on VR as a postoperative rehabilitation tool, its applications in the preoperative setting require further evaluation.

Discussion

VR applications are being investigated in many surgical and medical specialties. However, there is limited research on VR applications for patients undergoing abdominal surgery. The potential of VR in general surgical fields and populations is in fact limitless, and its impact throughout the patient journey (from preoperative preparation to postoperative rehabilitation) needs to be assessed further.

Benefits in the preoperative phase include augmented education and information. This could involve education about the patient’s current problem, approaches to surgery, possible risks and benefits, and what to expect from the day of admission to discharge. Optimising the physical fitness of patients can also be aided by prehabilitation programmes prior to surgery using VR fitness games. In addition, with the help of VR environments, patients could experience the pathway from admission to the operating theatre (including anaesthesia), decreasing stress related to surgery.

In the postoperative phase, with the favourable initial results in pain management and rehabilitation, patients undergoing major abdominal surgery could benefit from a VR environment as a distraction tool to lessen pain and as an engaging means of improving physical activity. VR applications need not be limited to the hospital admission setting and could also be adapted for use at home with the same purpose.

A good example would be for patients undergoing bowel screening. This could include VR applications in performing colonoscopy, and educating the patient on the procedure and what to expect alongside educational information about bowel preparation, which is essential prior to the procedure.39,40 With the help of the distractive properties of VR, this could also ease procedural discomfort and improve the overall experience.

Another example of VR use at home is for patients undergoing colorectal surgery. In the preoperative phase, patients could receive their preoperative planning in a virtual, patient friendly environment, with anatomy presentations showing which part of the colon or rectum is to be removed, how the connections are fashioned, education on stoma formation and post-surgery bowel function. In the perioperative phase, VR could aid short and long-term recovery in the form of physical rehabilitation, mental health support, and improving patient satisfaction and general wellbeing.

Despite its promising applications, as in any emerging technology, VR has its own initial obstacles to gaining traction in the healthcare system. These include the obvious cost of the systems and clinical validation, which can play a major role in limiting widespread adoption. Further delays in adoption would likely be seen owing to the required education of both healthcare providers and their patients, particularly with regard to the application and utilisation of VR technology. VR devices can be awkward to wear and their use will necessitate educational support. This requires the devices to have broad specifications that allow the applications to meet the wide patient and provider base while enabling customisation to the specific purpose at the same time.41

In addition, as the technology is in its infancy, many issues could still arise such as safety considerations and side effects.42 This will prompt the need to formally validate the applications of VR, and to standardise the use of VR for adoption in healthcare settings through collaboration between clinicians and developers.

Conclusions

VR shows great promise with regard to supporting the surgical patient through the patient pathway. Although it is currently some way from being a validated and reliable tool, further investment and research funding has huge potential returns in terms of quality of healthcare and patient satisfaction in the future.

References

- 1.Minderer M, Harvey CD, Donato F, Moser EI. Neuroscience: virtual reality explored. Nature 2016; 533: 324–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cipresso P, Giglioli IA, Raya MA, Riva G. The past, present, and future of virtual and augmented reality research: a network and cluster analysis of the literature. Front Psychol 2018; 9: 2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyaw BM, Saxena N, Posadzki Pet al. Virtual reality for health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the Digital Health Education collaboration. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e12959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L, Yu F, Shi Det al. Application of virtual reality technology in clinical medicine. Am J Transl Res 2017; 9: 3867–3880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregg L, Tarrier N. Virtual reality in mental health: a review of the literature. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007; 42: 343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallari B, Spaeth EK, Goh H, Boyd BS. Virtual reality as an analgesic for acute and chronic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res 2019; 12: 2053–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards B, Colman AW, Hollingsworth RA. The current and future role of the Internet in patient education. Int J Med Inform 1998; 50: 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowles RA, Moyer CA, Sonnad SSet al. Doctor–patient communication in surgery: attitudes and expectations of general surgery patients about the involvement and education of surgical residents. J Am Coll Surg 2001; 193: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paas F, Renkl A, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory: instructional implications of the interaction between information structures and cognitive architecture. Instr Sci 2004; 32: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lok B, Ferdig RE, Raij Aet al. Applying virtual reality in medical communication education: current findings and potential teaching and learning benefits of immersive virtual patients. Virtual Real 2006; 10: 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandrangi VC, Gaston B, Appelbaum NPet al. The application of virtual reality in patient education. Ann Vasc Surg 2019; 59: 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srikaran M, Pillai SA, Muir Ket al. The use of virtual reality (VR) technology to improve radiotherapy information for patients with breast cancer. Radiography 2020; 26: S34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao J, Liu S, Zhang Set al. Pilot study of a virtual reality educational intervention for radiotherapy patients prior to initiating treatment. J Cancer Educ 2022; 37: 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr E, Brockbank K, Allen S, Strike P. Patterns and frequency of anxiety in women undergoing gynaecological surgery. J Clin Nurs 2006; 15: 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston M. Anxiety in surgical patients. Psychol Med 1980; 10: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerbershagen HJ, Dagtekin O, Rothe Tet al. Risk factors for acute and chronic postoperative pain in patients with benign and malignant renal disease after nephrectomy. Eur J Pain 2009; 13: 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayyadhah Alanazi A. Reducing anxiety in preoperative patients: a systematic review. Br J Nurs 2014; 23: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koo CH, Park JW, Ryu JH, Han SH. The effect of virtual reality on preoperative anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maples-Keller JL, Bunnell BE, Kim SJ, Rothbaum BO. The use of virtual reality technology in the treatment of anxiety and other psychiatric disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2017; 25: 103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato K, Fukumori S, Matsusaki Tet al. Nonimmersive virtual reality mirror visual feedback therapy and its application for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: an open-label pilot study. Pain Med 2010; 11: 622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeffs D, Dorman D, Brown Set al. Effect of virtual reality on adolescent pain during burn wound care. J Burn Care Res 2014; 35: 395–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan JJ, Yeam CT, Kee HMet al. The use of pre-operative virtual reality to reduce anxiety in women undergoing gynecological surgeries: a prospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol 2020; 20: 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deo N, Khan KS, Mak Jet al. Virtual reality for acute pain in outpatient hysteroscopy: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2021; 128: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noben L, Goossens SM, Truijens SEet al. A virtual reality video to improve information provision and reduce anxiety before cesarean delivery: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 2019; 6: e15872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haisley KR, Straw OJ, Müller DTet al. Feasibility of implementing a virtual reality program as an adjuvant tool for peri-operative pain control; results of a randomized controlled trial in minimally invasive foregut surgery. Complement Ther Med 2020; 49: 102356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bekelis K, Calnan D, Simmons Net al. Effect of an immersive preoperative virtual reality experience on patient reported outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2017; 265: 1068–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding L, Hua H, Zhu Het al. Effects of virtual reality on relieving postoperative pain in surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2020; 82: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veldhuijzen G, Klaassen NJ, Van Wezel RJet al. Virtual reality distraction for patients to relieve pain and discomfort during colonoscopy. Endosc Int Open 2020; 8: E959–E966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding J, He Y, Chen Let al. Virtual reality distraction decreases pain during daily dressing changes following haemorrhoid surgery. J Int Med Res 2019; 47: 4,380–4,388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosso-Vázquez JL, Gao K, Wiederhold BK, Wiederhold MD. Virtual reality for pain management in cardiac surgery. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2014; 17: 371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiegel B, Fuller G, Lopez Met al. Virtual reality for management of pain in hospitalized patients: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0219115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topp R, Ditmyer M, King Ket al. The effect of bed rest and potential of prehabilitation on patients in the intensive care unit. AACN Clin Issues 2002; 13: 263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luther A, Gabriel J, Watson RP, Francis NK. The impact of total body prehabilitation on post-operative outcomes after major abdominal surgery: a systematic review. World J Surg 2018; 42: 2781–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu W, Zeng N, Pope ZCet al. Acute effects of immersive virtual reality exercise on young adults’ situational motivation. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim A, Darakjian N, Finley JM. Walking in fully immersive virtual environments: an evaluation of potential adverse effects in older adults and individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2017; 14: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian J, McDonough DJ, Gao Z. The effectiveness of virtual reality exercise on individual’s physiological, psychological and rehabilitative outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steffens D, Delbaere K, Young Jet al. Evidence on technology-driven preoperative exercise interventions: are we there yet? Br J Anaesth 2020; 125: 646–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y, Xie F, Bai Xet al. Educational virtual reality videos in improving bowel preparation quality and satisfaction of outpatients undergoing colonoscopy: protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e029483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palanica A, Docktor MJ, Lee A, Fossat Y. Using mobile virtual reality to enhance medical comprehension and satisfaction in patients and their families. Perspect Med Educ 2019; 8: 123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nichols S, Patel H. Health and safety implications of virtual reality: a review of empirical evidence. Appl Ergon 2002; 33: 251–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baniasadi T, Ayyoubzadeh SM, Mohammadzadeh N. Challenges and practical considerations in applying virtual reality in medical education and treatment. Oman Med J 2020; 35: e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]