Abstract

Pathogenic Yersinia species secrete virulence proteins, termed Yersinia outer proteins (Yops), upon contact with a eukaryotic cell. The secretion machinery is composed of 21 Yersinia secretion (Ysc) proteins. Yersinia pestis mutants defective in expression of YscG or YscE were unable to export the Yops. YscG showed structural and limited amino-acid-sequence similarities to members of the specific Yop chaperone (Syc) family of proteins. YscG specifically recognized and bound YscE; however, unlike previously characterized Syc substrates, YscE was not exported from the cell. These data suggest that YscG functions as a chaperone for YscE.

Several gram-negative bacterial pathogens use a specialized protein secretion system, termed the type-III secretion system, to subvert or destroy eukaryotic cells (10, 18). These systems are activated upon contact with a eukaryotic cell and function to translocate effector proteins from the cytosol of the bacterium directly into the cytosol of the eukaryotic cell (32). The type-III secretion system of the human pathogenic yersiniae (Yersinia enterocolitica, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and Yersinia pestis) is an archetype of these systems (10, 18). It consists of a secretion apparatus composed of approximately 21 Yersinia secretion (Ysc) proteins and a set of 12 Yersinia outer proteins (Yops) that are exported by the secretion apparatus. Translocated Yops function to disrupt the host's response to the pathogen. As a result, bacteria are able to circumvent the primary immune response of the host and survive within the host's tissues (10, 13).

The Yop virulence proteins and the components of the type-III secretion machinery are encoded on a ca. 70-kb virulence plasmid termed pCD1 in Y. pestis KIM (29). Genes encoding the components of the type-III secretion apparatus, termed ysc genes, are clustered within several large transcriptional units, which include yscBCDEFGHIJKLM (16, 25), yscNOPQRSTU (6), yscW (2), and yopNtyeAsycNyscXYV (36). Mutations in any of the ysc genes, with the exception of yscB (22) and yscH (3), completely abolish Yop secretion.

The majority of Ysc proteins are predicted to be localized to the bacterial cytoplasm or inner membrane; however, at least one outer membrane protein (YscC) and two outer membrane-linked lipoproteins (YscJ and YscW) have been identified (2, 23, 25). The yscD, yscJ, yscR, yscS, yscT, yscU, and yscV gene products are predicted to be integral inner membrane proteins with at least one hydrophobic membrane-spanning region (6, 25, 30). The yscE, yscF, yscG, yscI, yscK, yscL, yscN, yscQ, and yscY gene products are predicted to be cytoplasmic or peripheral membrane proteins (6, 20, 25), whereas several recent studies show that a portion of the yscO, yscP, and yscX gene products are secreted in vitro (12, 27, 28). Together, these proteins are thought to assemble into or assist in the assembly of a large multiprotein secretory complex that spans both the inner and outer membranes. Large multiprotein complexes corresponding to at least a portion of the type-III secretory machinery of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (24) and Shigella flexneri (7) were recently identified and visualized by electron microscopy.

Expression and secretion of Yops can be induced in vitro by growing bacteria at 37°C in medium lacking calcium; however, it is contact with the surface of a eukaryotic cell that triggers secretion in vivo (32). The targeting of proteins for export through the type-III secretion apparatus involves one or both of two identified secretion-targeting signals. One secretion signal has been identified within the sequences encoding the initial 15-amino-acid residues of YopE and YopN (4). This signal appears to be encoded in the mRNA sequence rather than the peptide sequence, suggesting a cotranslational mechanism for Yop secretion. A second secretion signal is dependent on the interaction of the secreted protein with an accessory protein termed a specific Yop chaperone (Syc) (37). The YopE protein contains both an mRNA signal and a SycE-dependent targeting signal (9). Each secretion signal can function independently to target YopE for secretion in vitro; however, both secretion signals are required for the translocation of YopE into a eukaryotic cell.

Syc chaperones are small (12- to 20-kDa), acidic cytoplasmic proteins that typically contain a putative carboxyl-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix and that specifically recognize an amino-terminal region of one or two specific Yops (38). The five Yersinia Syc chaperones that have been identified bind either effector Yops (SycE [14, 37] to YopE, SycH [38] to YopH, and SycT [19] to YopT) or Yops involved in the regulation of Yop secretion and/or translocation (SycD [26, 38] to YopB and YopD and SycN [11, 20] and YscB [22] to YopN). In addition to a role in secretion of their cognate Yop or Yops, these chaperones have also been suggested to function as bodyguards that prevent the premature interaction of their target substrates, possibly by binding interactive surfaces (5, 38, 40).

Recent data suggest that YscY, an essential component of the type-III secretion apparatus, exhibits many of the characteristics typically associated with Syc proteins (12). YscY is a small cytoplasmic protein that contains a predicted carboxyl-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix and that specifically binds to a coiled-coil region of YscX, a secreted component of the type-III secretion apparatus. Analysis of the other Ysc proteins revealed that YscG and YscI also possess many of the characteristics associated with Syc proteins. In this study, we show that YscG specifically binds to the smallest component of the type-III secretion apparatus, YscE. We also demonstrate that YscE is not a secreted constituent of the type-III secretion system like YscX but nevertheless directly interacts with a Syc-like chaperone.

Use of the yeast two-hybrid system to detect interactions between YscG and YscE.

YscG is a small (13-kDa), acidic (pI 6.3) cytoplasmic- or peripheral-membrane protein (31) that possesses many of the characteristics typically associated with Syc and/or Syc-like proteins, including the presence of a putative carboxyl-terminal amphipathic alpha-helical region (YscG amino acid residues 82 to 97) (33). We used the yeast two-hybrid system to identify a substrate for YscG. The interaction of hybrid proteins coded for by fusions between the entire yscE, yscF, yscG, yscH, yscI, yscK, yscL, yscN, yscQ, yscX, and yscY genes to sequences of plasmids pGAD424 and pGBT9 (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) encoding the GAL4 activation and DNA-binding domains, respectively, were measured by both colony lifts and quantitative liquid β-galactosidase assays as previously described (11).

Saccharomyces cerevisiae SFY526 cells containing both the pGAD424 and pGBT9 cloning vectors were used as negative controls. Cultures of these cells produced no β-galactosidase activity (<1.0 U), indicating that the isolated GAL4 activation and DNA-binding domains do not interact with each other. S. cerevisiae SFY526 cells containing pGAD-YscG and pGBT-YscE or the reciprocal pairing of pGAD-YscE with pGBT-YscG produced 120 and 134 U of β-galactosidase, respectively. This level of β-galactosidase was significantly greater than levels obtained from SFY526 transformed with control plasmids (pGAD424 and pGBT9) or plasmids containing gene fusions to yscF, yscH, yscI, yscK, yscL, yscN, yscQ, yscX, and yscY (<1.0 U). SFY526 transformed with pGAD-YscE and pGBT-YscE or pGAD-YscG and pGBT-YscG produced only basal levels of β-galactosidase (<1.0 U). These data suggest that YscE and YscG directly interact with one another.

Construction and phenotypic analysis of a Y. pestis yscE deletion mutant.

The yscE gene, located immediately upstream of yscD in the yscBCDEFGHIJKLM operon (25), encodes a putative protein of 66 amino acids, the smallest protein predicted to be encoded on plasmid pCD1. YscE has previously been shown to be required for the secretion of Yops in Y. enterocolitica (3). In order to confirm that YscE performs a similar function in Y. pestis, we constructed an in-frame deletion in yscE that eliminated the coding region for amino acids 9 to 39 using the PCR-ligation-PCR technique (1) and primers 5′-CCTCTGGGGGTATTTAGCG-3′, 5′-AACTCCTGTTGTCGTTTGG-3′, 5′-TGTGGCCATGCAGAGCGCGC-3′, and 5′-CACGGAGTCGCCGGCGATTAGG-3′. The ca. 2.0-kb amplified product containing a 93-bp deletion within yscE was inserted into the EcoRV site of the suicide vector pUK4134 (35), generating plasmid pUK4134.P40. Plasmid pUK4134.P40 was utilized to move the yscE deletion into the parent strain Y. pestis KIM8-3002 (39) as previously described (30), generating Y. pestis KIM8-3002.P40 (ΔyscE) (Fig. 1A). Plasmid pUK4134.15 (31), carrying an in-frame deletion within yscG that eliminates the coding regions for amino acids 73 to 99 of YscG, was used to create the yscG deletion mutant KIM8-3002.41 (ΔyscG) (Fig. 1A).

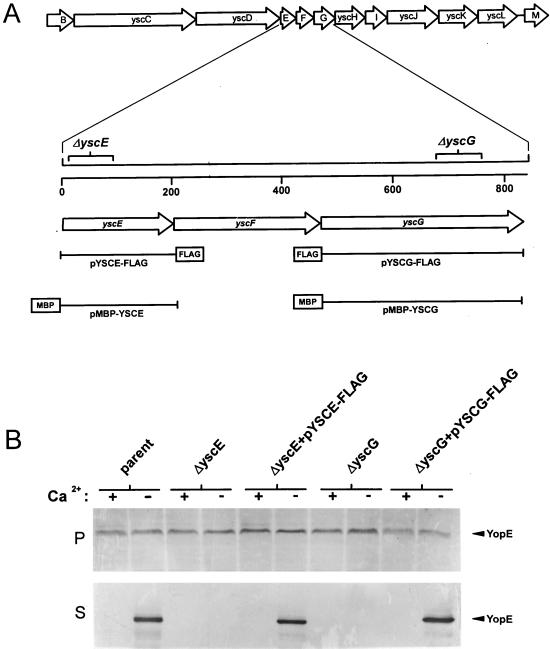

FIG. 1.

(A) Genetic organization of the yscEFG region of plasmid pCD1 in Y. pestis KIM. The locations of in-frame deletions within yscE and yscG are shown. Plasmids pYSCE-FLAG, pYSCG-FLAG, pMBP-YSCE, and pMBP-YSCG were used in complementation experiments. (B) Immunoblot analysis of culture supernatant and cell pellet fractions from Y. pestis strains grown at 37°C in the presence (+) or absence (−) of calcium. Antiserum specific for YopE was used to detect this protein in the cell pellet (P) and culture supernatant (S) fractions from Y. pestis KIM8-3002 (parent), the yscE deletion mutant (ΔyscE), the yscG deletion mutant (ΔyscG), and the yscE and yscG deletion mutants complemented with plasmids pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG, respectively.

Expression and identification of the YscE and YscG proteins were facilitated through construction of plasmids pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG, which express carboxyl-terminal FLAG-tagged YscE and amino-terminal FLAG-tagged YscG, respectively. PCR-amplified fragments of yscE and yscG tailed with HindIII and BglII restriction endonuclease sites were inserted into HindIII- and BglII-digested pFLAG-CTC and pFLAG-MAC (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), respectively. The recombinant YscE-FLAG protein expressed from plasmid pYSCE-FLAG is predicted to be expressed with an additional three amino-terminal residues (Met-Lys-Leu) and an additional 11 carboxyl-terminal residues (Arg-Ser-Val-Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys), which include the FLAG epitope (underlined). The recombinant YscG-FLAG protein is predicted to be expressed with an additional 12 amino-terminal residues (Met-Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys-Val-Lys-Leu), which also include a FLAG epitope (underlined).

Secretion of YopE by the parent strain Y. pestis KIM8-3002, the yscE deletion mutant KIM8-3002.40, the yscG deletion mutant KIM8-3002.41, and the yscE and yscG deletion mutants complemented with plasmids pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG, respectively, grown in TMH (15) at 37°C in the presence or absence of calcium was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting (Fig. 1B) as previously described (30). The yscE and yscG deletion mutants failed to secrete YopE at 37°C in the presence or absence of calcium. The parent strain and the yscE and yscG deletion mutants complemented with plasmids pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG secreted YopE under conditions permissive for Yop secretion. These data indicate that the absence of YopE secretion in the yscE and yscG deletion mutants was due to the lack of YscE or YscG and not to polar effects on downstream genes. These data also confirm that the addition of the FLAG epitope to the carboxyl terminus of YscE or to the amino terminus of YscG did not disrupt the function of these proteins in Yop secretion.

Identification and localization of the YscE-FLAG and YscG-FLAG proteins.

The FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma) was used to identify YscE-FLAG and YscG-FLAG in immunoblots from cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions of the parent Y. pestis KIM8-3002, the yscE and YscG deletion mutants, and the yscE and yscG deletion mutants complemented with pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG, respectively (Fig. 2A). An approximately 10-kDa protein was identified as YscE-FLAG in immunoblots from whole-cell fractions of the yscE deletion mutant complemented with plasmid pYSCE-FLAG. An approximately 15-kDa protein was identified as YscG-FLAG in immunoblots from whole-cell fractions of the yscG deletion mutant complemented with plasmid pYSCG-FLAG. YscE-FLAG and YscG-FLAG were not detected in the culture supernatant fractions. These data suggest that both YscE and YscG are cytoplasmic- or peripheral-membrane proteins that are not exported from the bacterial cell.

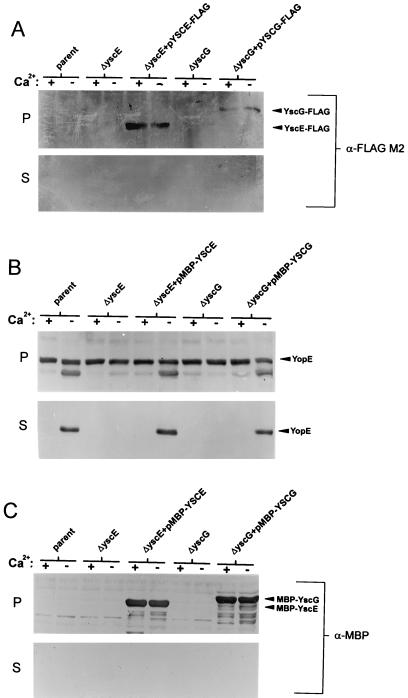

FIG. 2.

(A) Identification and localization of YscE-FLAG and YscG-FLAG. Bacterial strains were grown at 37°C in TMH with (+) or without (−) calcium. Proteins from cell pellet (P) fractions and culture supernatant (S) fractions of Y. pestis KIM8-3002 (parent), the yscE deletion mutant (ΔyscE), the yscG deletion mutant (ΔyscG), and the yscE and yscG deletion mutants complemented with pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG, respectively, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with the FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody. (B) Cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions from Y. pestis KIM8-3002 (parent), the yscE deletion mutant (ΔyscE), the yscG deletion mutant (ΔyscG), and the yscE and yscG deletion mutants complemented with pMBP-YSCE and pMBP-YSCG, respectively, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with a polyclonal antiserum specific for YopE or (C) the E. coli MBP.

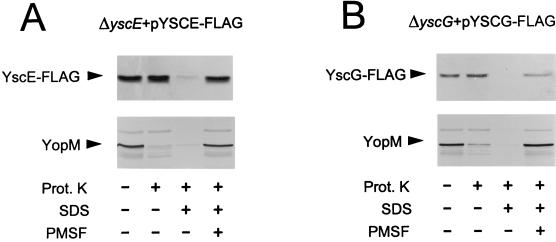

Several type-III secretion components, including TyeA, have been suggested to be exported to the cell surface but not released into the culture supernatant (21). To determine if YscE or YscG are surface exposed, the susceptibility of these proteins to exogenously added proteinase K was investigated. The yscE and yscG deletion mutants complemented with pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG, respectively, were grown at 37°C in the absence of calcium for 4 h prior to assessing the proteinase K accessibility of these proteins. Bacterial pellets corresponding to 1 ml of culture at an optical density at 620 nm of 1.0 (approximately 5.8 × 108 cells) were resuspended in 100 μl of TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]) or in TBS containing (i) 20 μg of proteinase K per ml; (ii) 20 μg of proteinase K per ml and 0.5% SDS; or (iii) 20 μg of proteinase K per ml, 0.5% SDS, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and proteinase K proteolysis was subsequently terminated by the addition of PMSF (1 mM) to all samples. Treated cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with the FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody or with antiserum specific for YopM. Proteinase K digested a significant portion of the secreted YopM protein (34) in both the presence and absence of SDS, confirming that YopM is accessible to proteinase K on the surface of cells (Fig. 3). No proteolytic degradation of either YscE-FLAG or YscG-FLAG was detected in cells treated with proteinase K in the absence of detergent. Disruption of the cellular membranes with detergent allowed degradation of both YscE-FLAG and YscG-FLAG, confirming the susceptibility of these proteins to proteolytic degradation. No proteolytic degradation of YscE-FLAG, YscG-FLAG, or YopM was detected in the presence of PMSF. These data indicate that YscE and YscG are not exported to the surface of the bacteria.

FIG. 3.

Protease accessibility of YscE-FLAG and YscG-FLAG in whole bacterial cells. (A) The yscE deletion mutant (ΔyscE) and (B) the yscG deletion mutant (ΔyscG) complemented with pYSCE-FLAG and pYSCG-FLAG, respectively, were grown for 5 h at 37°C in the absence of calcium. Approximately 5.8 × 108 bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in 100 μl of TBS with or without 20 μg of proteinase K (Prot. K) per ml, 0.05% SDS, or 1 mM PMSF. After 30 min at room temperature, proteolysis was terminated by the addition of PMSF (1 mM). Proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with the FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody or with a polyclonal antiserum specific for the secreted YopM protein.

Previous studies have shown that YscX, a secreted component of the type-III secretion apparatus, when fused to the carboxyl terminus of the Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein (MBP), is no longer exported from the cell (12). As a consequence, an MBP-YscX-expressing construct cannot complement the defect in Yop secretion associated with a yscX deletion mutant. We used a similar approach to confirm that YscE and YscG function within the bacterial cell. PCR-amplified fragments tailed with PstI and EcoRI sites corresponding to the entire yscE and yscG open reading frames were inserted into plasmid pMAL-c2 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), generating plasmids pMBP-YSCE and pMBP-YSCG, respectively. The yscE and yscG deletion mutants carrying pMBP-YSCE and pMBP-YSCG, respectively, secreted YopE at 37°C in the absence of calcium, indicating that the MBP-YscE and MBP-YscG proteins were functional (Fig. 2B). Analysis of immunoblots with an antiserum specific for MBP demonstrated that MBP-YscE and MBP-YscG were exclusively associated with the cell pellet fraction (Fig. 2C). These data confirm that YscE and YscG are cytoplasmic- or peripheral-membrane proteins that function within the bacterial cell.

FLAG-tagged YscG recognizes and directly binds an MBP-YscE hybrid protein.

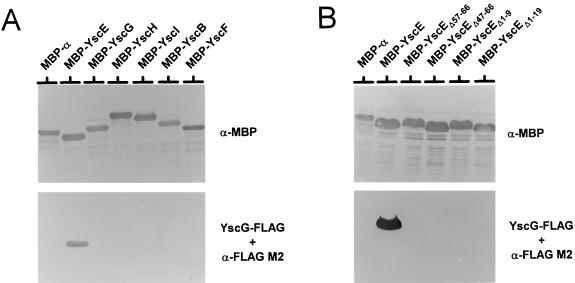

Previous studies have demonstrated that YscY, the specific chaperone for the secreted YscX protein, specifically binds to MBP-YscX that has been transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (12). In order to confirm the interaction between YscE and its putative chaperone YscG, we performed a similar protein affinity blot experiment using an E. coli BL21 (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) cell extract containing FLAG-tagged YscG to probe Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) containing MBP, MBP-YscE, MBP-YscG, MBP-YscH, MBP-YscI, MBP-YscF, and MBP-YscB hybrid proteins (Fig. 4A). The location of the individual MBP fusions was detected on a duplicate blot using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific for E. coli MBP (5-prime, 3-prime, Inc., Boulder, Colo.). Bound YscG-FLAG was detected with the FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody. YscG-FLAG specifically bound to MBP-YscE but not to MBP-YscG, MBP-YscH, MBP-YscI, MBP-YscB, and MBP-YscF, confirming that YscG and YscE interact with one another.

FIG. 4.

Binding of YscG-FLAG to MBP-YscE. (A) Cell pellet fractions from E. coli BL21 expressing MBP, MBP-YscE, MBP-YscG, MBP-YscH, MBP-YscI, MBP-YscB, or MBP-YscF were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes. (B) Immobilon-P membranes containing cell pellet fractions from strain BL21 expressing MBP, MBP-YscE, or truncated MBP-YscEΔ57–66, MBP-YscEΔ47–66, MBP-YscEΔ1–9 or MBP-YscEΔ1–19. MBP migrated more slowly than expected due to an in-frame fusion between malE and the vector LacZ α-peptide encoding sequences (MBP-α). (A and B) A cytoplasmic extract from BL21 carrying pYSCG-FLAG was used to probe the Immobilon-P membranes containing the SDS-PAGE-separated MBP and MBP derivatives. Bound YscG-FLAG was detected with the FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody. MBP and the MBP derivatives were detected with a polyclonal antiserum specific for the MBP portion of the hybrid proteins.

To localize the region of YscE recognized by YscG, we constructed derivatives of plasmid pMAL-c2 carrying truncated versions of the yscE gene encoding MBP-YscE hybrid proteins lacking amino acid residues 1 to 9, 1 to 19, 57 to 66, or 47 to 66 of YscE. The truncated MBP-YscE hybrid proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes and detected with antiserum specific for the MBP portion of the hybrid protein or probed with an E. coli BL21 cell extract containing FLAG-tagged YscG (Fig. 4B). YscG-FLAG bound to the full-length MBP-YscE hybrid protein; however, deletion of sequences encoding the amino- or carboxyl-terminal 10 or 20 residues of YscE prevented the interaction of YscG with the YscE portion of the hybrid proteins. These data suggest that even small deletions at the amino or carboxyl terminus of YscE either eliminate residues essential to the YscG-YscE interaction or disturb the tertiary structure of YscE in a manner incompatible with YscG binding.

The cytoplasmic YscG protein shares structural (size, pI, carboxyl-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix) and limited amino-acid-sequence similarities with the other members of the Syc family (YscG exhibits between 12 and 22% identity with SycE, SycH, SycN and YscY [17]). In addition, YscG, like the other Syc proteins, specifically recognizes and binds to another protein, YscE, that is encoded in close proximity to the gene encoding its Syc-like chaperone (yscG). Proteins recognized by previously characterized Syc and Syc-like proteins are secreted proteins; however, YscE is a cytoplasmic- or peripheral-membrane protein that is not exported from the cell. Thus, YscE is the first example of a cytoplasmic- or peripheral-membrane protein that is specifically recognized by a Syc-like chaperone. In addition, YscE and YscG represent only the second example of a Syc-like chaperone and substrate that are required for the formation of an export-competent type-III secretion system (12).

Previous studies have shown that YscX, like YscO (27) and YscP (28), is a secreted component of the type-III secretion system; however, an MBP-YscX fusion protein was not secreted and could not complement a yscX deletion mutant (12). Similarly, attachment of YopE to the carboxyl terminus of neomycin phosphotransferase prevented the export and function of the resultant neomycin phosphotransferase-YopE hybrid protein (4). In contrast, we demonstrated that an MBP-YscE hybrid protein was able to fully complement a yscE deletion mutant, confirming that YscE functions intracellularly. Similarly, expression of an MBP-YscG hybrid protein complemented a yscG deletion mutant, indicating that YscG, like all known Syc and Syc-like proteins, functions intracellularly.

SycE has been shown to form a homodimer (8, 37). We have previously used the yeast two-hybrid system to detect both the SycE-SycE interaction and the SycE-YopE interaction (11). Interestingly, no YscG-YscG interaction was detected using the yeast two-hybrid system. Similarly, no YscY-YscY interaction was detected using the yeast two-hybrid system (12). These data suggest either that the Syc-like YscG and YscY proteins function as monomers or that the yeast two-hybrid system failed to detect the YscG-YscG and YscY-YscY interactions.

Syc proteins perform a critical role in the secretion and translocation of a number of the Yop virulence proteins; however, the exact function of these proteins is still a matter of contention. SycE has been suggested to play a direct role in the secretion and translocation of YopE, which infers a direct interaction between SycE and components of the secretion and translocation machinery (8, 9). Other data suggest that SycE acts as a bodyguard, preventing interaction of YopE with other cytosolic type-III components prior to export (5, 40). SycE is also required for expression of stable soluble cytosolic YopE, suggesting that SycE functions to maintain YopE in a secretion-competent state (8, 14). Although YscE is not secreted, YscG may also function to maintain a stable cytoplasmic pool of YscE or to prevent the premature interaction of YscE with other components of the secretion apparatus. In either case, YscG is the first example of a Syc-like protein that binds an exclusively intracellular protein.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Stanley Glaser Foundation and by Public Health Service Grant AI39575.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali S A, Steinkasserer A. PCR-ligation-PCR mutagenesis: a protocol for creating gene fusions and mutations. BioTechniques. 1995;18:746–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allaoui A, Scheen R, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Cornelis G R. VirG, a Yersinia enterocolitica lipoprotein involved in Ca2+ dependency, is related to exsB of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4230–4237. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4230-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allaoui A, Schulte R, Cornelis G R. Mutational analysis of the Yersinia enterocolitica virC operon: characterization of yscE, F, G, I, J, K required for Yop secretion and yscH encoding YopR. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:343–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson D M, Schneewind O. A mRNA signal for the type III secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. Science. 1997;278:1140–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett J C Q, Hughes C. From flagellum assembly to virulence: the extended family of type III export chaperones. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:202–204. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01751-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman T, Erickson K, Galyov E, Persson C, Wolf-Watz H. The lcrB (yscN/U) gene cluster of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is involved in Yop secretion and shows high homology to the spa gene clusters of Shigella flexneri and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2619–2626. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2619-2626.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blocker A, Gounon P, Larquet E, Niebuhr K, Cabiaux V, Parsot C, Sansonetti P. The tripartite type III secretion of Shigella flexneri inserts IpaB and IpaC into host membranes. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:683–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng L W, Schneewind O. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion: on the role of SycE in targeting YopE into HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22102–22108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng L W, Anderson D M, Schneewind O. Two independent type III secretion mechanisms for YopE in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:757–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3831750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelis G R, Wolf-Watz H. The Yersinia Yop virulon: a bacterial system for subverting eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:861–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2731623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day J B, Plano G V. A complex composed of SycN and YscB functions as a specific chaperone for YopN in Yersinia pestis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:777–788. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day J B, Plano G V. The Yersinia pestis YscY protein directly binds YscX, a secreted component of the type III secretion machinery. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1834–1843. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1834-1843.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallman M, Andersson K, Hakansson S, Magnusson K E, Stendahl O, Wolf-Watz H. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis inhibits Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in J774 cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3117–3124. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3117-3124.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frithz-Lindsten E, Rosqvist R, Johansson L, Forsberg Å. The chaperone-like protein YerA of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis stabilizes YopE in the cytoplasm but is dispensible for targeting to the secretion loci. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:635–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goguen J D, Yother J, Straley S C. Genetic analysis of the low calcium response in Yersinia pestis Mu d1(Ap lac) insertion mutants. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:842–848. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.842-848.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddix P L, Straley S C. Structure and regulation of the Yersinia pestis yscBCDEF operon. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4820–4828. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4820-4828.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene. 1988;73:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hueck C J. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iriarte M, Cornelis G R. YopT, a new Yersinia Yop effector protein, affects the cytoskeleton of host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:915–929. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iriarte M, Cornelis G R. Identification of SycN, YscX, and YscY, three new elements of the Yersinia Yop virulon. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:675–680. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.675-680.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iriarte M, Sory M P, Boland A, Boyd A P, Mills S D, Lambermont I, Cornelis G R. TyeA, a protein involved in control of Yop release and in translocation of Yersinia Yop effectors. EMBO J. 1998;17:1907–1918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson M W, Day J B, Plano G V. YscB of Yersinia pestis functions as a specific chaperone for YopN. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4912–4921. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4912-4921.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koster M, Bitter W, de Cock H, Allaoui A, Cornelis G R, Tommassen J. The outer membrane component, YscC, of the Yop secretion machinery of Yersinia enterocolitica forms a ring-shaped multimeric complex. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:789–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6141981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubori T, Matsushima Y, Nakamura D, Uralil J, Lara-Tejero M, Sukhan A, Galan J E, Aizawa S I. Supramolecular structure of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Science. 1998;280:602–605. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michiels T, Vanooteghem J-C, de Rouvroit C L, China B, Gustin A, Boudry P, Cornelis G R. Analysis of virC, an operon involved in the secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4994–5009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.4994-5009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neyt C, Cornelis G R. Role of SycD, the chaperone of the Yersinia Yop translocators YopB and YopD. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:143–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payne P L, Straley S C. YscO of Yersinia pestis is a mobile core component of the Yop secretion system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3882–3890. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3882-3890.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Payne P L, Straley S C. YscP of Yersinia pestis is a secreted component of the Yop secretion system. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2852–2862. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2852-2862.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perry R D, Straley S C, Fetherston J D, Rose D J, Gregor J, Blattner F R. DNA sequencing and analysis of the low-Ca2+-response plasmid pCD1 of Yersinia pestis KIM5. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4611–4623. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4611-4623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plano G V, Straley S C. Multiple effects of lcrD mutations in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3536–3545. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3536-3545.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plano G V, Straley S C. Mutations in yscC, yscD, and yscG prevent high-level expression and secretion of V antigen and Yops in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3843–3854. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3843-3854.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosqvist R, Magnusson K, Wolf-Watz H. Target cell contact triggers expression and polarized transfer of Yersinia YopE cytotoxin into mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1994;13:964–972. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schiffer M, Edmundson A B. Use of helical wheels to represent the structures of proteins and to identify segments with helical potential. Biophys J. 1967;7:121–135. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(67)86579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skrzypek E, Cowan C, Straley S C. Targeting of the Yersinia pestis YopM protein into HeLa cells and intracellular trafficking to the nucleus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1051–1065. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skrzypek E, Haddix P L, Plano G V, Straley S C. New suicide vector for gene replacement in yersiniae and other gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid. 1993;29:160–163. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viitanen A-M, Toivanen P, Skurnik M. The lcrE gene is part of an operon in the lcr region of Yersinia enterocolitica 0:3. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3152–3162. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3152-3162.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wattiau P, Cornelis G R. SycE, a chaperone-like protein of Yersinia enterocolitica involved in the secretion of YopE. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wattiau P, Woestyn S, Cornelis G R. Customized secretion chaperones in pathogenic bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams A W, Straley S C. YopD of Yersinia pestis plays a role in negative regulation of the low-calcium response in addition to its role in translocation of Yops. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:350–358. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.350-358.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woestyn S, Sory M P, Boland A, Lequenne O, Cornelis G R. The cytosolic SycE and SycH chaperones of Yersinia protect the region of YopE and YopH involved in translocation across eukaryotic cell membranes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;6:1261–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]