Abstract

Introduction

The ear, nose and throat (ENT) emergency clinic is managed by foundation year (FY) doctors from taking referrals to discharging patients, under the supervision of a registrar. FYs learn essential skills and knowledge on how to manage common ENT problems. The clinic is often overloaded because of a high patient demand, and this limits the opportunities for teaching. We hypothesised that the clinic bookings would be better managed if referrals from general practitioners (GPs) were triaged by registrars.

Methods

Telephone referrals from GPs for the ENT emergency clinic were directed to the on-call ENT registrar, between 8am and 1pm from Monday to Friday, and to the FY outside of this period. Consecutive referrals to the emergency clinic were analysed in a baseline audit and a post-intervention cycle.

Results

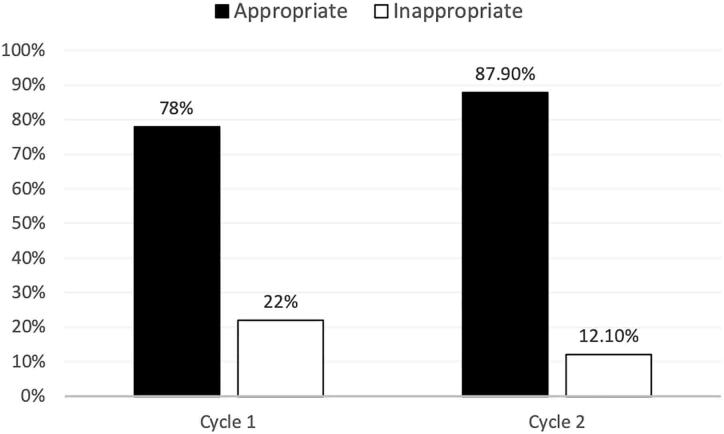

A total of 646 and 611 patients were given clinic appointments in the first and second cycles, respectively. Clinic session overbookings decreased from 85% to 46.3%. Appointments for referrals that were deemed inappropriate had reduced from 22% to 12.1%.

Discussion and Conclusion

Involvement of a registrar in taking referrals for the ENT emergency clinic was associated with a reduction in clinic overbookings. It is feasible and productive to involve a senior decision maker in the operational management of the emergency clinic, while preserving the delivery of this service by FYs for its training value.

Keywords: Otolaryngology, Quality improvement, Urgent care clinics, Referral and consultation

Introduction

The ear, nose and throat (ENT) emergency clinic is an integral feature of many ENT units in the UK. It plays an essential role in meeting the service needs of patients with acute ENT presentations, and alleviating pressures in general practice and emergency departments (EDs). The emergency clinic is a victim of its own success, as the clinic is frequently overloaded.1–4 This adds to trainee stress and anxiety, and may limit opportunities for teaching in the clinic.

The on-call foundation year doctor (FY) is responsible for taking referrals and running the ENT emergency clinic under supervision.2 The FYs are therefore the primary gatekeepers to this clinic.

We hypothesised that senior expertise may lessen the burden of overbooking. We implemented and studied an intervention that enabled registrars to take telephone referrals for the emergency clinic from general practitioners (GPs).

Methods

Intervention

In July 2019 the hospital switchboard at our district general hospital was instructed to transfer all GP telephone calls to the on-call ENT registrar on duty between the hours of 8am and 1pm from Monday to Friday. This period was chosen because the on-call FY reported that this was generally the busiest part of their day, juggling ward work and telephone referrals.

Our ENT department took the decision to free the on-call registrar from service provision, including routine outpatient clinics and elective theatres, during this period so that they could dedicate their time to support the emergency service. The on-call ENT registrar was therefore readily accessible to take telephone calls from GPs and supervise the FY in the emergency clinic. Outside of these hours, the normal practice of referring to the on-call FY remained in place.

Audit cycles

A retrospective audit was conducted over four months (March to June 2019). This baseline audit evaluated all the ENT conditions that were booked into the emergency clinic. All of the bookings were accepted by the on-call FY, which was usual practice prior to the intervention. The FYs were given a guideline that listed the conditions to accept into the emergency clinic as part of their induction prior to our audit.

Following the intervention, a second audit cycle was conducted retrospectively for four months (August to November 2019). The primary outcome measure of this study was the number of clinic bookings. Our emergency clinic capacity was in agreement with ENT UK’s recommendation of six patients per session.5 Therefore, an overbooking was defined as a clinic with patient numbers beyond this limit. The secondary outcome measure was a comparison of appropriate and inappropriate ENT conditions accepted into the emergency clinic, according to our local referral criteria.

Results

There were 646 and 611 patients in the first and second cycles, respectively. The median number of patients booked into the clinic reduced from an overbooked state to the appropriate number, as listed in Table 1. The reduction in the number of clinic bookings is illustrated in Figure 1. The ratio of appropriate and inappropriate referrals had also improved, as displayed in Figure 2. The mix of cases that were booked into the emergency clinic and deemed appropriate and inappropriate are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1 .

Median number of patients per morning clinic sessions (six slots) and full-day sessions (12 slots) (range in parentheses)

| Cycle 1 | Cycle 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 6-patient session | 8 (6–9) | 6 (5–13) |

| 12-patient session | 14 (7–16) | 12 (3–15) |

Figure 1 .

Percentage of clinics that were underbooked, overbooked and neutral in cycles 1 (n = 60) and 2 (n = 67)

Figure 2 .

Proportion of clinic bookings deemed appropriate and inappropriate in cycles 1 (n = 646) and 2 (n = 611)

Table 2 .

Percentage of all cases booked into the emergency clinic that were deemed appropriate in cycles 1 and 2

| Appropriate conditions | Cycle 1 (%) (n = 504) |

Cycle 2 (%) (n = 537) |

|---|---|---|

| Otitis externa | 46.6 | 51.4 |

| Nasal fracture | 9.4 | 14.7 |

| Epistaxis | 10.5 | 8.0 |

| Foreign body ear | 5.6 | 6.2 |

| Vocal cord check | 2 | 3.3 |

| Facial palsy | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| Ramsay Hunt syndrome | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Sensorineural deafness | 2.6 | 2.8 |

Table 3 .

Percentage of all cases booked into the emergency clinic that were deemed inappropriate in cycles 1 and 2

| Inappropriate conditions | Cycle 1 (%) (n = 142) | Cycle 2 (%) (n = 74) |

|---|---|---|

| Wax | 5.9 | 1.3 |

| Bleeding canal | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Otitis media | 4 | 1.6 |

| Otalgia | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Postop complication | 0.6 | 2.0 |

| Pinna abscess | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Wound review | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Foreign body throat | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Dizziness | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Post discharge review | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| Chronic ear discharge | 0 | 0.2 |

| Pinna haematoma | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Deafness secondary to trauma | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Cautery review | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Conductive deafness | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Audiogram | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| Pinna cellulitis | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Nasal abscess | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Sinusitis | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Ear laceration | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Painful neck swelling | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Dysphagia | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Septal perforation | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Tympanic membrane perforation | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Grommet review | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Facial palsy secondary to trauma | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Facial palsy secondary to infection | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Nasal polyp | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| Tonsillitis | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| CSF rhinorrhoea | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Ear canal fracture | 0.2 | 0.0 |

Discussion

Historically, the ENT emergency clinic operated on an open-access ‘walk-in’ policy.6 The transition to an appointment-based clinic reduced clinic attendance by 43% in one unit.1 The appointment-based model became widely adopted by ENT units in the UK. The next phase of the evolution of the emergency clinic was simply introducing a step that required a referrer to talk to an ENT FY, which reduced inappropriate referrals from 7% to 2% in one study.2

We evaluated the effect of redesigning the referral pathway so that registrars directly took GP telephone referrals for a period of their on-call shift. The premise was that the greater specialty-specific knowledge possessed by registrars would confer an advantage over FYs in triaging referrals for the emergency clinic, and therefore reduce clinic overbookings by giving specialist advice over the phone.

Summary of findings and comparison with existing literature

The key finding of our study was that the emergency clinic overbookings dramatically decreased from 85% to 46.3% as a result of the registrars taking telephone referrals from GPs. The median number of patients booked into the 6-slot half-day clinics reduced from 8 to 6, and those into the 12-slot full-day clinics reduced from 14 to 12, matching the ENT UK recommendations on safe clinic numbers.5 Ibrahim et al3 demonstrated a similar reduction in the average number of patients per clinic from 9.8 to 7.2 after implementing a referral guideline.

Our results demonstrated a reduction in the proportion of inappropriate ENT conditions booked into the clinic from 22% to 12.1%. Others have achieved similar reductions. Ibrahim et al3 demonstrated a reduction in inappropriate bookings from 18% to 5%, and Mahalingam et al4 showed a decrease from 31% to 16%, after both groups had introduced a referral guideline.

Previous studies have looked at reducing the number of inappropriate conditions seen in the emergency clinic by focusing on a referral guideline for FYs.3,4 Our audit is novel as we have used a senior clinician in place of a referral guideline as our intervention. Two studies have looked at senior involvement in the emergency clinic.7,8 However, unlike our study, which evaluated the impact of senior involvement at the point of referral, the other two groups investigated senior presence within the clinic itself and demonstrated a reduction in the number of patients repeatedly brought back for further reviews.7,8

Our study has identified tangible differences between FYs and registrars in their pattern of clinic booking. Our findings build a compelling case for the involvement of senior clinicians in the process of emergency clinic bookings in order to improve outpatient clinic efficiency.

Explanation of the observed findings

The clinic overbookings were considerably reduced with the introduction of the registrar triaging intervention. It is likely that the observed reduction in clinic overbookings was because registrars appropriately redirected GPs to other acute specialties, or other suitable ENT referral pathways such as consultant clinics or subspecialty clinics, or simply provided clinical advice to GPs that allowed patients to be managed completely in primary care. The details of the telephone discussions between the registrars and GPs were not recorded in our audit, and therefore we are unaware of what happened to patients that were not booked into the emergency clinic. In order to maintain the flow of patients we have designed a local referral pathway (Figure 3) that lists the various types of ENT conditions and where they may be optimally managed.

Figure 3 .

Our local hospital referral pathway for acute ear, nose and throat (ENT) conditions

Limitations

Only switchboard calls from GPs were the subject of our audit. All ED referrals continued to be directed to the FY via the hospital internal bleep system even during the period between 8am and 1pm, and therefore these referrals were not amenable to the registrar intervention. This limitation had a negative impact on the potential effect size of the audited intervention.

There is some uncertainty over whether the improvement between the two cycles was due to the registrar intervention or an increase in the experience of the FYs as they spent more time in their post, which may have confounded our findings. However, this is unlikely as the two audit cycles were conducted with two separate groups of FYs that had changed over in August 2019.

Our experience

The intervention reaped several direct benefits for our patients, FYs and registrars. It benefited patients as a reduction in inappropriate clinic utilisation led to an increase in availability of clinic slots, which we were able to give to patients with conditions in most need of this clinic.

The FY in the clinic appreciated the extra time available for teaching and completing work-based assessments with their supervising registrars. The on-call FY also expressed relief that they had less interruption to their ward work because the switchboard had redirected GP telephone calls to the on-call registrar.

ENT registrars have a requirement to maintain a logbook of emergency cases that have been discussed with them during the course of their training. They felt their on-call time was well spent in providing clinical advice to GPs, and likewise GPs undoubtedly appreciated having a discussion with a more senior member of the ENT team.

Further work

There is a trend toward transforming services to address pressures in the non-elective ENT workload. The recent Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) report9 had identified that some ENT units have provided a middle grade or consultant-led on-call service during daytime hours, and gained benefit from senior involvement at this level. This type of on-call interface aligns ENT with most other surgical specialties that already provide a senior-led on-call service. Although the benefits of senior involvement are clear in our study, the autonomy and training opportunities for FYs in triaging skills may be hindered by our intervention. This may lead to a generation of clinicians lacking these skills. A potential solution to this may be for senior clinicians to review rather than take over FYs’ triaging decisions, which may achieve the efficiency we have demonstrated without encroaching on the training needs of junior doctors. Such approaches require further research and evaluation.

Conclusion

We evaluated the effect of involving the on-call ENT registrar in triaging GP telephone referrals for the emergency clinic. This intervention was found to be a beneficial, pragmatic and progressive strategy in managing the non-elective ENT workload. A reduction in overfilling and inappropriate bookings for the ENT emergency clinic was achieved, and this allowed us to maintain this service as an essential educational resource for junior doctors rotating through ENT.

Authors’ contributions

Zahir Mughal: project conception, literature review, data collection, article writing.

James Seigel: project conception, data collection, reviewing and editing.

Syamaprasad Basu: project conception, supervision, reviewing and editing.

References

- 1.Smyth C, Moran M, Diver Cet al. Rapid access rather than open access leads to improved effectiveness of an ENT emergency clinic. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2013; 2: u200524.w996. 10.1136/bmjquality.u200524.w996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mylvaganam S, Patodi R, Campbell JB. The ENT emergency clinic: A prospective audit to improve effectiveness of an established service. J Laryngol Otol 2009; 123: 229–233. 10.1017/S0022215108003022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibrahim N, Virk J, George Jet al. Improving efficiency and saving money in an otolaryngology urgent referral clinic. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3: 495–498. 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i6.495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahalingam S, Seymour N, Pepper Cet al. Reducing inappropriate referrals to secondary care: our experiences with the ENT emergency clinic. Qual Prim Care 2014; 22: 251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jardine A, Moorthy R, Watters G. ENT UK outpatients review and recommendations. ENT UK, 2017. https://www.entuk.org/general-guidelines. (cited August 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wheatley AH, Temple RH, Camilleri AEet al. ENT open access clinic: an audit of a new service. J Laryngol Otol 1999; 113: 657–660. 10.1017/s0022215100144767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirza A, McClelland L, Daniel Met al. The ENT emergency clinic: does senior input matter? J Laryngol Otol 2013; 127: 15–19. 10.1017/S0022215112002538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishpool SJC, Stanton E, Chawishly E-Ket al. Audit of frequent attendees to an ENT emergency clinic. J Laryngol Otol 2009; 123: 1242–1245. 10.1017/S0022215109990478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall A. Ear, nose and throat surgery GIRFT programme national specialty report. NHS England and NHS Improvement; 2019. https://www.GettingItRightFirstTime.co.uk (cited August 2020). [Google Scholar]