Abstract

Introduction

We investigated all-cause mortality following emergency laparotomy at 1 and 5 years. We aimed to establish a basis from which to advise patients and relatives on long-term mortality.

Methods

Local data from a historical audit of emergency laparotomies from 2010 to 2012 were combined with National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) data from 2017 to 2020. Covariates collected included deprivation status, preoperative blood work, baseline renal function, age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, operative time, anaesthetic time and gender. Associations between covariates and survival were determined using multivariate logistic regression and Kaplan–Meier analysis. We used patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy between 2015 and 2020 as controls.

Results

ASA grade was the best discriminator of long-term outcome following laparotomy (n=894) but was not a predictor of survival following cholecystectomy (n=1,834), with mortality being significantly greater in the laparotomy group. Following cholecystectomy, 95% confidence intervals for survival at 5 years were 98–99%. Following laparotomy these intervals were: ASA grade 1, 79–96%; ASA grade 2, 69–82%; ASA grade 3, 44–58%; ASA grade 4, 33–48%; and ASA grade 5, 4–51%. The majority of deaths occurred after 30 days.

Conclusions

Emergency laparotomy is associated with a significantly increased risk of death in the following 5 years. The risk is strongly correlated to ASA grade. Thirty-day mortality estimation is not a good basis on which to advise patients and carers on long-term outcomes. ASA grade can be used to predict long-term outcomes and to guide patient counsel.

Keywords: Emergency, Laparotomy, Mortality, Surgical time, Scoring, Counsel

Introduction

Patients undergoing an emergency laparotomy expect some information on the likelihood of their death. This information is vital to satisfy the principle of primum non nocere. There is an understandable concern of bias in having the surgeon estimate the risk, and any objective quantification can appear seductively convenient.

The long-term outcome after emergency laparotomy is poorly evidenced. Although they were designed to audit surgical services, there is increasing use of 30-day mortality estimates in decision making. We were interested in assessing long-term outcome, that this might form the basis of evidenced patient advice.

The most contemporary tool that we have to estimate mortality from an emergency laparotomy is the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) mortality risk score.1 Our hospital participates in a very similar Scottish equivalent of the NELA, known as the Emergency Laparoscopic and Laparotomy Scottish Audit (ELLSA) which also utilises preoperative NELA scoring to guide management.

NELA scoring is heavily influenced by similar systems that preceded it, particularly the Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity (POSSUM) and its successor P-POSSUM.2,3 All three of these scores were conceived to audit surgical services and not as a basis for preoperative counsel. Many of the required elements used to predict mortality, eg blood loss and degree of peritoneal soiling, are only known postoperatively.

An additional complication of the NELA prediction algorithm is that, like P-POSSUM, it was developed with a logistic regression model. It is based only on the binary outcome of dead or alive by 30 postoperative days and cannot comment on prognosis beyond this.

Evaluation of surgical services and patient counsel are quite distinct aims with regard to the certainty we can offer in our conclusions. There are two primary reasons for having low confidence in long-term estimates of survival for a patient preoperatively. The first is a low volume of reporting of long-term follow-up for emergency laparotomy. The second is the mathematically insoluble difficulty in applying population-based estimates to individual patients.4

The online NELA prediction tool is commendably clear in the advice it gives on counsel. Despite this, in the absence of any other objective estimates, and in the time-sensitive context of an emergency laparotomy, it is surprising how much clinical discussion can hinge on the 30-day mortality estimate. We are concerned that patients cannot reasonably be advised on the likelihood of being alive after 30 days should they proceed.

There is little evidence on long-term mortality after laparotomy to guide a more patient-centred discussion. Some patients may begin a protracted decline following laparotomy. Although they ultimately die as a result of their presenting pathology, operation or its attendant complications, this occurs at temporal distance from the procedure. Providing this information would enable patients to make an informed decision. It would also be useful in managing expectations should they proceed. We were interested in determining what long-term mortality from emergency laparotomy actually is and the factors that might allow it to be predicted.

Methods

There were three periods of data collection. The first was from 2010 to 2012. Basic demographics for all patients undergoing emergency laparotomy were recorded prospectively using the electronic theatre management system. Identified cases were cross-checked with paper records of theatre bookings and case notes to determine the indications for surgery. Coding errors, indications due to gynaecologic, urologic, aortic or similar vascular pathology, and cases of appendicitis or cholecystitis that required open conversion were excluded. These patients would not typically be offered preoperative NELA risk scoring. These data were collected in line with local audit guidelines and stored securely on a local database. The demographic data for these patients, together with an observation that older patients tended to have poor prognosis, were published in 2018.5

The second period of data collection began in 2017 as part of our requirement to contribute patient-level information to ELLSA. This database was maintained prospectively by a senior nurse with dedicated time for regular review of theatre booking forms, review of notes on discharge and electronic theatre system data. The database is uploaded monthly to the national ELLSA database.

In May 2020, a medical records query was submitted for the date of death of all patients, in both databases.

Patients under 16 years old were excluded. The resulting data, with basic patient demographics, date of death and date of surgery for 953 patients, were combined into a single csv file. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores were also available for 894 patients. In addition, age, data on preoperative blood results (haematocrit, neutrophil count, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, creatinine and albumin) and baseline creatinine were available. With the exception of baseline creatinine, the blood results included were those drawn closest to the point of going into theatre. To this were added information on the duration of surgery and of anaesthetic induction and the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SMID16) quintile of patients. Analysis was conducted in RStudio v. 1.3.959 with R v. 3.5.1 ‘Feather Spray’; using the latest dplyr,6 ggplot2,7 survminer, pROC8 and survival R packages.

The third period of data collection relates to patients undergoing a cholecystectomy. The data were collected from the regional electronic theatre management system, providing 1,834 patients with recorded ASA grade and date of laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed between 2015 and 2020. These patients were followed up to 1 August 2020 at which point the dates of death were recorded. The survival data were used as a control group for the emergency laparotomy group. We thus hoped to separate out the effect of major operative intervention from the need for general anaesthetic in the context of age and comorbidities.

This project was undertaken in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki using data gathered locally as part of a government-sanctioned national audit (see https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/13211/scottish-government-health-and-social-care-resources/modernising-patient-pathways-programme/emergency-laparotomy-and-laparoscopic-scottish-audit-ellsa) and using older data gathered as part of a local audit, which was granted local Caldicott Guardian approval.

Results

Demographics

Median follow-up after laparotomy was 495 days, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 143–2,788 days and a range of 1 day to 9.96 years for all patients studied. Overall, the median age was 67 years with an IQR of 52–77 years and was similar across collection time points. In total, 482 women and 471 men were included.

Thirty-day mortality rates following laparotomy were not significantly different across collection time points (ie before and after NELA) with 11.9% for the period 2010–2012 and 10.9% for 2017–2020 (Kaplan–Meier, plot not shown, p=0.62). Findings of malignancy were documented only for the NELA cohort, and 23% (110 of 475) of laparotomies had a diagnosis of malignancy on discharge.

There were 953 laparotomy patients in total. Of these, 894 had ASA grade available for analysis. The number of available data points for each preoperative blood result was as follows: albumin n=858, creatinine n=858, CRP n=832, haematocrit n=833, neutrophils n=832, and for baseline creatinine n=840. Missing values were not replaced. The types of operations performed are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 .

Summary of procedures

| Operation | Number of procedures |

|---|---|

| Stoma formation | 162 |

| Small bowel resection | 157 |

| Other | 117 |

| Colectomy: right (including ileocaecal resection) | 114 |

| Adhesiolysis | 111 |

| Repair of intestinal perforation | 55 |

| Colectomy: subtotal or panproctocolectomy | 49 |

| Colectomy: left (including anterior resection) | 40 |

| Peptic ulcer suture or repair of perforation | 31 |

| Washout only | 25 |

| Exploratory/relook laparotomy only | 18 |

| Intestinal bypass | 15 |

| Repair or revision of anastomosis | 15 |

| gastroenterostomy | 11 |

| Colorectal resection – other | 7 |

| Gastrectomy – partial or total | 6 |

| Haemostasis | 6 |

| Drainage of abscess/collection | 5 |

| Gastric surgery – other | 3 |

| Laparostomy formation | 1 |

| Negative laparotomy | 1 |

| Peptic ulcer – oversew of bleed | 1 |

| Removal of foreign body | 1 |

| Resection of Meckel’s diverticulum | 1 |

| Resection of other intra-abdominal tumour(s) | 1 |

Summary of case mix of all laparotomies included in the study, n=953. Hartman’s procedures have been included as ‘Stoma formation’ and ‘Other’ includes those procedures which were not recorded and those which were less common, such as splenectomy or pancreatic necrosectomy

With regard to the data on laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the median follow-up was 1042 days with an IQR of 627–1,495 days. Median age was 53 years with an IQR of 39–64 years.

Analysis

When considering differences between covariates for those patients who were alive and dead at 5 years post emergency laparotomy, there were a number of significant relationships (Table 2). However, most of these were strongly correlated to ASA. The effect of a small volume of extreme results and the zero-bound meant that most results were non-parametric and so were analysed with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Table 1 indicates what we would consider to be a representative case mix of an unselected take. Surgical time is therefore a reasonable proxy measure for complexity. Perhaps surprisingly, there was no association of surgical time with mortality. Anaesthetic time was significantly increased in patients who went on to die but was also correlated to ASA. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was 0.23 (p≤0.0001) for ASA and anaesthetic time, 0.39 (p≤0.0001) for ASA and patient age, −0.12 (p=0.0009) for ASA and albumin, and 0.19 (p≤0.001) for ASA and baseline creatinine. However, ASA was not well correlated with surgical time (−0.05, p=0.12) or haematocrit (−0.07, p=0.036). Therefore, it does not appear that surgeons were self-policing surgical time by abbreviating operations in more unstable patients.

Table 2 .

Comparison of covariates by mortality at 5 years post emergency laparotomy

| Factor | Deceased or alive at 5 years | 1st Quartile | Median | 3rd Quartile | Wilcoxon rank sum, unpaired, two-tailed test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Deceased | 64 | 73 | 80 | <0.001 |

| Alive | 47 | 64 | 74 | ||

| Albumin (g/dl) | Deceased | 24 | 29 | 35 | 0.011 |

| Alive | 24 | 32 | 38 | ||

| Anaesthetic time (min) | Deceased | 44 | 61 | 85 | <0.001 |

| Alive | 40 | 50 | 70 | ||

| ASA | Deceased | 3 | 3 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Alive | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Baseline creatinine (μmol/l) | Deceased | 50 | 66 | 81 | 0.0007 |

| Alive | 50 | 60 | 74 | ||

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | Deceased | 56 | 73 | 107 | 0.11 |

| Alive | 55 | 69 | 92 | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | Deceased | 17 | 60 | 163 | 0.25 |

| Alive | 19 | 70 | 207 | ||

| Haematocrit | Deceased | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| Alive | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.43 | ||

| Neutrophils ×109/l | Deceased | 5.0 | 7.7 | 12.2 | 0.10 |

| Alive | 5.45 | 8.6 | 12.9 | ||

| Sex | Deceased | Male=155; Female=162 | 0.82 | ||

| Alive | Male=316; Female=320 | ||||

| SMID 16 Quintile | Deceased | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.65 |

| Alive | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Surgical time (min) | Deceased | 44 | 61 | 85 | 0.21 |

| Alive | 40 | 50 | 70 | ||

Importantly there is a high correlation between American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade and most of the significant relationships, see the text for further details. Significant values are highlighted in bold.

A multiple logistic regression analysis of all covariates determined those that were most decisive (Figure 1). The most parsimonious model included only the ASA, age (years), CRP level, divided into high or low by its median value of 65, and the haematocrit value, being most relevant when the haematocrit was below the bounds of the normal range. By far the greatest effect was from ASA (odds ratio (OR) 2.65, p<0.001). Age correlated highly with ASA. Once the impact of ASA was accounted for, the absolute contribution of age to risk was small, but non-trivial, and is given here as increased OR per extra year above 16 (OR 1.03, p<0.001). There is an accumulation of risk in the very old but, according to this model, the magnitude of this is less than advancing one ASA grade until the age of 104; and having a low haematocrit at age 17 is equivalent in risk to being 47 years old. Therefore, age is an important, but secondary, consideration. Using this logistic model, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve with reasonable utility could be generated to predict 5-year mortality with an area under the curve (AUC) of 77.8% (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Odds ratio of logistic regression for 5-year mortality and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Using all of the covariates listed in Table 1, the most parsimonious logistic regression had only four factors: American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, haematocrit and age. Odds ratios were generated from this logistic regression. Notably, the effect of age was highly statistically significant and the odds ratio shown refers to each increase in age by one year. Adverse prognosis from low preoperative CRP possibly relates to early operation for acute presentations of serious pathologies. The median CRP was 65, values below this were interpreted as ‘low’ and values above this as ‘high’. Haematocrit was divided into high, low and normal based on our laboratory normal range of 0.4–0.52. These cut-offs, and the decision to consider age as a continuum rather than a series of discrete ranges, were examined by locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS). It is notable that there is actually very little increased risk of death beyond 75 years of age. Here N=782 as this was the number of patients that had all relevant factors recorded. Using this logistic regression model, an ROC curve could be generated demonstrating reasonable accuracy of the model with an area under the curve (AUC) of 77.8%.

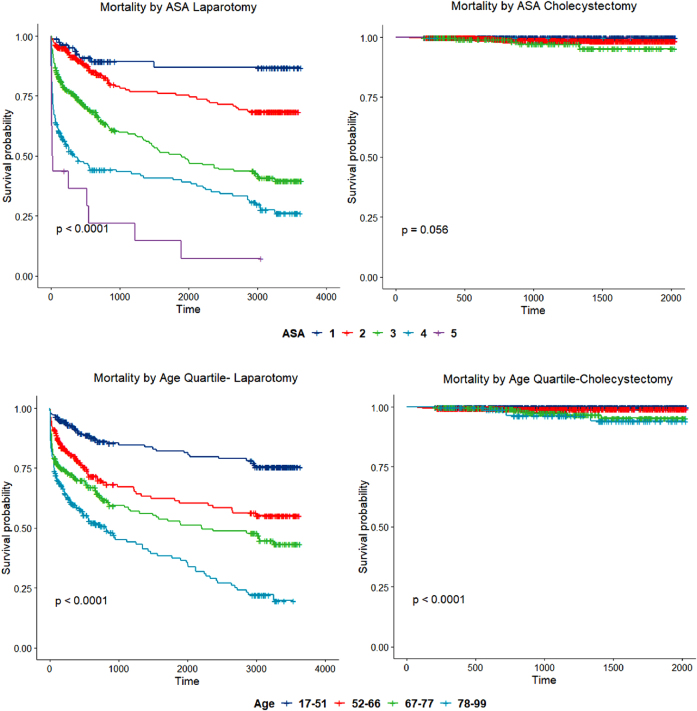

Having found ASA to be decisive by multiple logistic regression, we compared data on long-term mortality by ASA between laparoscopic cholecystectomy and emergency laparotomy cohorts (Figure 2). There was a significant difference in survival between ASA grades in patients after emergency laparotomy, whereas there was no difference in survival between ASA grades following cholecystectomy (95% confidence interval (CI) for 5-year survival, 0.98–0.99). The difference in mortality between corresponding ASA grades in laparotomy and cholecystectomy groups was significant (p<0.05) for all grades except ASA grade 5, where numbers were low in both cohorts (Table 3).

Figure 2 .

Mortality following laparotomy and mortality following cholecystectomy by American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade and age. The upper two panels compare mortality stratified by ASA in emergency laparotomy and cholecystectomy. Time is shown in days. The difference in mortality between corresponding ASAs in laparotomy and cholecystectomy groups was significant at an alpha of 0.05 for all groups except ASA grade 5, where numbers were low in both cohorts, see Table 2. Mortality by ASA following laparotomy (n=894) was: ASA 1=86, ASA 2=281, ASA 3=323, ASA 4=188 and ASA 5=16. Mortality by ASA following cholecystectomy (n=1,834) was: ASA 1=598, ASA 2=1,055, ASA 3=173, ASA 4=6 and ASA 5=2. The lower two panels compare mortality stratified by age in emergency laparotomy and cholecystectomy. Time is shown in days. Ages were grouped by quartiles derived from the emergency laparotomy group. The difference in mortality was significant when comparing quartiles across laparotomy and cholecystectomy groups, all with p<0.0001. Mortality by age following laparotomy (n=950): 17–51 years=233, 52–66 years=224, 67–77 years=252 and 78–99 years=241. Mortality by age following cholecystectomy (n=1,834) 17–51 years=853, 52–66 years=592, 67–77 years=286 and 78–99 years=103.

Table 3 .

Proportion of patients surviving emergency laparotomy by American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade, data from Kaplan–Meier curves.

| Time | Number at risk | Number of deaths | Survival proportion | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Comparison with cholecystectomy with same ASA grade (Kaplan–Meier) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA 1 | ||||||

| 30 days | 85 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1 | |

| 1 year | 67 | 4 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.99 | |

| 2 years | 44 | 3 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.97 | |

| 5 years | 33 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.96 | p<0.0001 |

| ASA 2 | ||||||

| 30 days | 274 | 7 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | |

| 1 year | 195 | 16 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.95 | |

| 2 years | 124 | 13 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.89 | |

| 5 years | 101 | 12 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.82 | p<0.0001 |

| ASA 3 | ||||||

| 30 days | 297 | 26 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.95 | |

| 1 year | 184 | 51 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.80 | |

| 2 years | 114 | 22 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.71 | |

| 5 years | 79 | 22 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.58 | p<0.0001 |

| ASA 4 | ||||||

| 30 days | 133 | 56 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.77 | |

| 1 year | 76 | 37 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.57 | |

| 2 years | 57 | 8 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.52 | |

| 5 years | 48 | 5 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.48 | p=0.03 |

| ASA 5 | ||||||

| 30 days | 7 | 9 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.76 | |

| 1 year | 5 | 1 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.71 | |

| 2 years | 3 | 2 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.58 | |

| 5 years | 2 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.51 | p=0.063 |

This table refers to the survival of all patients following emergency laparotomy for whom an ASA grade was recorded (n=894). Note that, if 100% accurate, all of the patients who died after the 30-day Rubicon would have been quoted a 0% 30-day mortality risk by current scoring algorithms. For the ASA grades with the highest volume of deaths (3 and 4), the majority of the deaths take place after 30 postoperative days. Actual survivorship, at 5 years, of patients with an ASA grade of 3 or 4 is approximately 50%. Emergency laparotomy (n=894): ASA grade 1=86, ASA grade 2=281, ASA grade 3=323, ASA grade 4=188 and ASA grade 5=16. These patients were compared with patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy with the same ASA by Kaplan–Meier analysis to generate the p-values shown. Cholecystectomy patients (n=1,834): ASA grade 1=598, ASA grade 2=1,055, ASA grade 3=173, ASA grade 4=6 and ASA grade 5=2.

For the ASA grades with the highest volume of deaths (3 and 4), the majority in the emergency laparotomy group take place after 30 postoperative days (Table 3). Actual survivorship at 5 years of patients with an ASA grade of 3 or 4 is approximately 50% (Table 3).

Based on the Kaplan–Meier curve in Figure 2 a survival table of pertinent time points (Table 3) can be generated to guide long-term prognosis estimates prior to emergency laparotomy.

Discussion

Limitations and interpretation

We do not have detailed information on the final pathology for all these patients but we know that only 23% of those in the NELA cohort (n=475) left hospital with a cancer diagnosis. Our primary interest was in establishing a basis from which patients could be advised on long-term prognosis even when the underlying diagnosis was not clear or not definitively established. This is the situation that actually faces patients presenting for emergency laparotomy. Clearly, resection of a locally advanced colorectal cancer will have been the indication in some cases and this will have some bearing on long-term mortality. However, there are a number of reasons why we do not think we are simply reporting cancer deaths by proxy. The most obvious is that death from cancer is a function of disease stage and not of ASA. Although we accept that the two factors will compound, if cancer deaths were the main cause of the long-term mortality we describe, it seems unlikely that ASA would have proven so useful a predictor by itself. In a national study involving 8077 patients, the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland found that ASA contributed significantly more to 30-day mortality than Dukes’ classification.9 This effect was so marked that, for those with an ASA over 3 the 30-day mortality was similar whether or not the cancer was resected.9 This would support the hypothesis that the physiologic reserve is decisive, at least in the early postoperative period. Our contention is that this influence persists for longer than is generally appreciated and irrespective of underlying pathology. The main task is often to navigate poor reserve in the context of an inflammatory response, not the underlying pathology per se.

What is novel about our analysis is the question of whether these factors can be utilised to provide long-term prognostic information. Most studies of long-term all-cause mortality from colorectal cancer use age rather than ASA. We have shown that, in our population, the two are highly correlated with age contributing little prognostic information beyond ASA. The median age of our patients is 67 years. Colorectal cancer in this age range would be expected to have a 5-year mortality of less than 30%.10 It seems unlikely that colorectal cancer would be able to explain 5-year mortality rates of 50% and 60% in our ASA grade 3 and 4 patients. In addition, emergency procedures and advancing ASA have been found to be poor prognostic indicators in patients with colorectal cancer, independent of stage.9–11 Although there are some studies that suggest that ASA is not important for postoperative survival,12 these have often focused on specific procedures, of high operative risk, where the group who refused operation are not analysed, and those that undergo it are likely to be subject to selection bias.

There is also the pattern of deaths to be considered. There is a very marked decrease in survival in the first 1,000 days after operation. Thereafter, mortality continues at a far slower rate. Nonetheless, the rate varies in a statistically significant manner between ASA cohorts. This would be a very unusual survival pattern for any cancer and is not typical of colorectal cancer.10

This pattern of data, with a strong explanatory power of age and ASA, even for mortality temporally distant from surgery, suggests a physiologic explanation for long-term mortality. The systemic insult of the initial pathology, compounded by major surgery, is likely to require a significant period of convalescence. It is probable that patients are more vulnerable to further insults, such as community-acquired infections, which they otherwise may have had the reserve to weather. They may enter a general decline in this fashion from which it is difficult to retrieve them. This is consistent with the finding of the independent risk factor of low haematocrit because it is also a non-specific indicator of poor functional reserve.

ASA will be heavily influenced by baseline organ impairment and this will associate with the limits of organ reserve. However, chronological age will limit maximal possible physiologic compensation, and such limitation may not manifest in everyday activity. From this perspective, it is understandable that age would have a significant impact beyond its correlation with ASA (Figure 1).

Therefore, we do not think that it is a limitation of the study that the emergency laparotomy patients would have been displaying an inflammatory response while the cholecystectomy controls would not. Rather, this is part of the effect that we are trying to control for.

Implications for future practice

In the immediate term, we must think very carefully before using the NELA score to inform discussions around consent for emergency laparotomy. If the score suggests a high risk of death, this is salient information. However, the majority of postoperative deaths will take place outside NELA’s 30-day predictive window. These deaths are not an inevitable consequence of age or comorbidities, otherwise they would appear in the cholecystectomy data set too. Rather, they relate to the patients’ inability to adequately respond to the physiologic test of an emergency laparotomy.

The NELA tool is invaluable in identifying those patients who are likely to need level two or level three care postoperatively. Such stratification can form the basis of much needed perioperative algorithms and allow for better in-patient care. However, the impact of such stratification on long-term prognosis is uncertain and untested. What we provide here is a means of guiding patient counsel around laparotomy, for an unknown pathology, in the emergency setting.

ASA was the most important decider of long-term outcome following laparotomy after multiple logistic regression but is not linked to survival probability following cholecystectomy. In this sense, it is likely the operative intervention, rather than the patients’ poor pre-morbid status, which relates to all-cause mortality. It would be reasonable to counsel patients on these grounds.

In the majority of cases, should emergency laparotomy have been avoided, outcomes would have been considerably worse. However, we are minded to investigate how best to advise patients considering the offer of an emergency laparotomy. They are more likely to be interested in all-cause mortality than a definitive mechanistic linkage between surgical insult and death. Emergency laparotomy and its attendant complications or procedures impose a considerable burden of protracted suffering on patients. It would be useful to have some objective information on long-term mortality that would allow them to assess the bargain. We would consider the idea that ASA score is correlated with postoperative mortality to be uncontroversial.13–16 Nonetheless, its ability to discriminate rates of mortality in the long-term following emergency laparotomy has been unstudied until now and represents valuable information for patient counsel. A kappa score for inter-rater variability in ASA grading has been stable at 0.4 for many years17 but discordance is rarely by more than one grade.17 A consensus between two anaesthetists would be helpful when using the score for prognostication and will be most important in deciding between ASA 2 and 3 where the survival difference is most marked.

Conclusion

ASA is the primary determinant of long-term mortality following emergency laparotomy, with a smaller secondary influence of age, CRP and haematocrit. Mortality is more convincingly caused by a combination of underlying pathology and surgery, rather than intrinsic effects of ASA or age, given the cholecystectomy control group. Future work in this area could usefully focus on whether frailty scores could significantly improve such prognostication. Together they might be used to guide plans for escalation of care.

Long-term prognosis is the patient’s primary interest. The 95% confidence bounds for survival by ASA grade in Table 2 are a reasonable replacement for the complete unknown. However, the compounding effect of age should also be a consideration. A practical conclusion from the data presented here is that, at an ASA grade above 2, 5-year mortality from emergency laparotomy approximates to 50%. This may be a useful starting point for discussions with family and patients alike who have a natural tendency to consider laparotomy as a success/fail event followed by return to previous levels of activity.

References

- 1.Eugene N, Oliver CM, Bassett MGet al. Development and internal validation of a novel risk adjustment model for adult patients undergoing emergency laparotomy surgery: the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit risk model. Br J Anaesth 2018; 121: 739–748. 10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prytherch DR, Whiteley MS, Higgins Bet al. POSSUM and Portsmouth POSSUM for predicting mortality. Physiological and operative severity score for the enUmeration of mortality and morbidity. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 1217–1220. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M. POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 355–360. 10.1002/bjs.1800780327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson R, Keiding N. Individual survival time prediction using statistical models. J Med Ethics 2005; 31: 703–706. 10.1136/jme.2005.012427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibrahim B, Ibrahim I, Wilson Met al. High mortality at 30 days and 1 year following emergency admission to general surgery in the over 70 age group. International Journal of Surgery 2018; 55: S115. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.05.554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickham H, Grolemund G. R for Data Science: Import, Tidy, Transform, Visualize, and Model Data. First edition. ed. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly; 2016. xxv, 492 pages p. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadley W. Ggplot2. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard Aet al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12: 77. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tekkis PP, Poloniecki JD, Thompson MR, Stamatakis JD. Operative mortality in colorectal cancer: prospective national study. BMJ 2003; 327: 1196. 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bos A, Kortbeek D, van Erning FNet al. Postoperative mortality in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: The impact of age, time-trends and competing risks of dying. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019; 45: 1575–1583. 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weerink LBM, Gant CM, van Leeuwen BLet al. Long-Term survival in octogenarians after surgical treatment for colorectal cancer: prevention of postoperative complications is Key. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 3874–3882. 10.1245/s10434-018-6766-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chijiiwa K, Yamaguchi K, Yamashita Het al. ASA physical status and age are not factors predicting morbidity, mortality, and survival after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am Surg 1996; 62: 701–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sauvanet A, Mariette C, Thomas Pet al. Mortality and morbidity after resection for adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: predictive factors. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201: 253–262. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daabiss M. American society of anaesthesiologists physical status classification. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55: 111–115. 10.4103/0019-5049.79879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauh MA, Krackow KA. In-hospital deaths following elective total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2004; 27: 407–411. 10.3928/0147-7447-20040401-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolters U, Wolf T, Stützer H, Schröder T. ASA classification and perioperative variables as predictors of postoperative outcome. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia 1996; 77: 217–222. 10.1093/bja/77.2.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley R, Holman C, Fletcher D. Inter-rater reliability of the ASA physical status classification in a sample of anaesthetists in Western Australia. Anaesth Intensive Care 2014; 42: 614–618. 10.1177/0310057X1404200511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]