Abstract

Introduction

Men with gynaecomastia are routinely referred to breast clinics, yet most do not require breast surgical intervention. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of a novel point-of-care gynaecomastia decision infographic in primary care on the assessment, management and referral practices to tertiary breast surgical services.

Methods

A study was carried out of male patient referrals from primary care in Greater Manchester to a tertiary breast centre between January and March in 2018–2020. Referral patterns were compared before and after the infographic went live in general practices in Greater Manchester in January 2020. Data were collected for gynaecomastia referrals, including aetiology, investigation and management.

Results

In total, 394 men were referred to a tertiary breast centre from 163 general practices, of which 271 (68.8%) had a diagnosis of gynaecomastia. Use of the decision infographic by primary healthcare providers was associated with a decrease in male breast referrals with gynaecomastia (79.6% to 62.0%). Fewer gynaecomastia patients were referred with a benign physiological or drug-related cause after implementation of the infographic (52.2% vs 41.8%). Only 10 (3.7%) patients with gynaecomastia underwent breast surgery during the study period.

Conclusion

Implementation of a gynaecomastia infographic in primary care in Manchester was associated with a reduction in gynaecomastia referrals to secondary care. We hypothesise that implementation of the infographic into primary care nationally may potentially translate to hundreds of patients receiving more specialty-appropriate referrals, improving overall management of gynaecomastia. Further study is warranted to test this hypothesis.

Keywords: Gynaecomastia, Breast, Primary healthcare, Infographics, Referral

Introduction

Gynaecomastia is defined as the enlargement of the male breast due to hyperplasia of the glandular tissue around the nipple.1 It may present clinically or asymptomatically in one or both breasts and is driven by alterations in the male oestrogen and testosterone ratio.2 Physiological gynaecomastia is common in the newborn, adolescents and older men and most do not require investigation.3 Drugs, illnesses, environmental exposures and genetic conditions may further increase the risk.4 Primary breast cancer, although rare, is an important differential.5 Most gynaecomastia is benign in its aetiology, and few patients presenting to primary care with the condition warrant specialist breast referral6 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Indication for direct referral of gynaecomastia to specialist breast units

The challenge for primary and secondary care providers is to identify the most appropriate care setting in which to manage patients presenting with gynaecomastia. Many men with gynaecomastia are routinely referred to UK breast clinics,7,8 despite this being a suboptimal place for the assessment and diagnosis of most patients with the condition. Few patients require surgical intervention for gynaecomastia,9 and initial assessment should be balanced between primary care and medical endocrinology.6 Onward referral from the breast clinic to another, more appropriate discipline may result in delay in the assessment and treatment of these patients.9

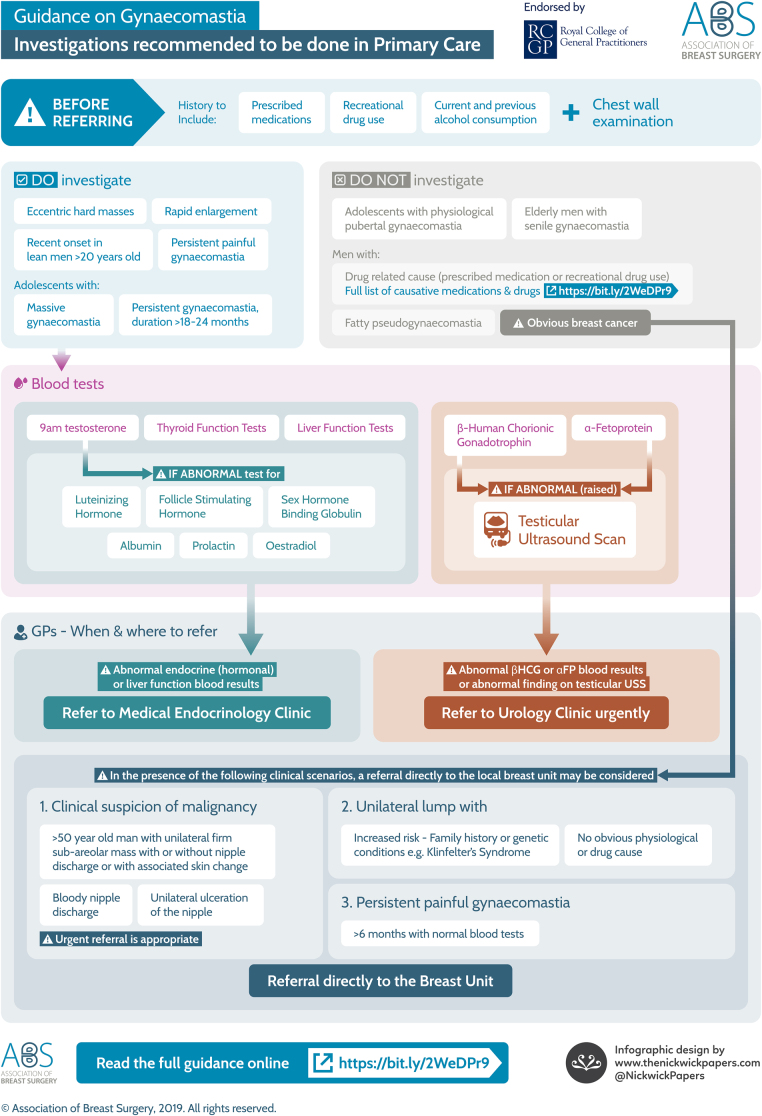

Best practice guidelines for the assessment, investigation and management of gynaecomastia were updated in 2019 by the Association of Breast Surgery (ABS)6 to optimise the patient pathway between primary and secondary care. These guidelines were used to develop a point-of-care decision infographic for use by primary healthcare providers to summarise a best practice pathway for the assessment and management of gynaecomastia6 (Figure 2). The objective of the infographic was to facilitate the referral pathway of gynaecomastia patients to appropriate secondary care settings. In all patients presenting with gynaecomastia, a detailed history (including prescribed and recreational drug use) and chest wall examination is advised, with further investigations (eg liver, kidney and thyroid function tests, hormonal profile) undertaken, if applicable, to facilitate appropriate specialty referral.

Figure 2 .

Primary care infographic for gynaecomastia

Patient pathway algorithms have been utilised before in primary care to summarise new guidelines, facilitate decision-making and reduce unnecessary referrals to specialist services.10,11 Studies have demonstrated an improvement in rates of preventative health monitoring,12 improved referral patterns in paediatric and dermatological settings13,14 and better compliance with adverse drug event documentation15 following the introduction of decision or assessment tools in general practice.

This study aimed to assess how the implementation of gynaecomastia decision infographic in primary care would impact upon the practices, assessment and referral patterns for gynaecomastia patients from general practice to tertiary breast services in Greater Manchester. Any potentially positive impact would be treated as hypothesis-generating data to lead to further study on a larger, possibly national, scale.

Methods

Design

Clinical outcomes and demographic data were examined for all male patients referred to a single tertiary breast centre between January and March over three consecutive years. Data were collected in 2018, 2019 and 2020 to coincide with referral practices (i) before the ABS update and (ii) after the ABS update/implementation of the intervention.

To control for possible national variations in referral practices that may have inadvertently influenced our results, data were compared with the number of male referrals to Liverpool Breast Unit, a similar sized, geographically separated breast unit in the North West of England.

Participants and setting

All new male referrals to the breast clinic at the South Manchester Breast Unit, Manchester, between January and March were included from 2018 to 2020. Figures for gynaecomastia referrals were compared as percentages of all new male referrals, so that numbers were not skewed by the merging of regional breast services in 2020. Figures were compared before and after implementation of the infographic to ascertain the potential impact of the intervention.

Intervention

Professional assistance was sought to produce an infographic tool for primary care which highlighted the appropriate assessment (in primary care) and referral patterns to secondary care, if necessary, for male patients presenting with gynaecomastia. The primary care infographic was developed with Nickwick Papers graphic design,16 local general practitioners (GPs), medical endocrinologists and surgeons and was reviewed by the Association of Breast Surgery Clinical Practice & Standards Committee.

The infographic was approved for use by the relevant local primary care authorities and went ‘live’ throughout Greater Manchester in January 2020. The tool could be used for each patient presenting to their GP with gynaecomastia. Upon entering the diagnosis code for gynaecomastia on to the primary care software, the infographic appeared on their screen with advice on investigation, management and potential referral pathways. The infographic included both benign and pathological gynaecomastia presentation and best referral practice between breast, urology and medical endocrinology services.

Funding was provided by the Association of Breast Surgery. Information technology (IT) support was provided by the IT department of Manchester Clinical Commissioning Group. Governance approval was obtained from Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (Audit ID: 8961).

Data collection

A local clinical results database was used to collect clinical and demographic data. Patient notes were checked for all male patients referred to the tertiary breast centre, and lists of new referrals were obtained from the audit department at Wythenshawe hospital.

Data collected were: route of referral, reason for referral, diagnosis, age of patient, new gynaecomastia diagnosis, aetiology of gynaecomastia, total number of new male referrals and total number of all new patient referrals to the tertiary breast clinic. Confidential items or patient identifiers were not required or recorded.

Statistical analysis

All data were recorded and evaluated using Microsoft Excel (version 2017). Data were analysed descriptively using counts and percentages for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for continuous measures, where normally distributed.17 Differences were tested using paired t-tests and chi-square tests, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 8,693 new patients were referred to a tertiary breast centre from 163 General Practices and four secondary centres in Greater Manchester during the months January to March inclusive over the three-year study period. There were 394 (4.5%) new male referrals, of which 271 (68.8%) had a diagnosis of gynaecomastia. A total of 157 (57.9%) patients had bilateral gynaecomastia, 72 (26.6%) left and 42 (15.5%) right. Average age was 48 years (SD 21.4). The total number and percentage of patients referred by year is listed in Table 1.

Table 1 .

Referrals from primary care to the South Manchester breast unit from January to March inclusive during the study year (2020) and two previous years

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total all new breast referrals | 2,675 | 3,159 | 2,859 | 8,693 |

| Total new male breast referrals, N (%) | 113 (4.2%) | 123 (3.9%) | 158 (5.5%) | 394 (4.5%) |

| Total new gynaecomastia referrals | 90 | 83 | 98 | 271 |

| Primary care | 87 | 80 | 97 | 264 |

| Secondary care | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| % total male new referrals with gynaecomastia | 79.6% | 67.5% | 62.0% | 68.8% |

| Non-gynaecomastia male referrals | 23 | 40 | 60 | 123 |

| Non-gynaecomastia male aetiology: N (%) | ||||

| Abscess/infection | 1 (4.3) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (1.9) | 5 (4.3) |

| Cyst | 3 (13.0) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (7.4) | 12 (10.3) |

| Breast cancer | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (1.7) |

| Other cancer | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.6) | 4 (3.4) |

| Lipoma | 6 (26.1) | 7 (17.5) | 6 (11.1) | 19 (16.2) |

| Lymph node | 0 (0) | 3 (7.5) | 6 (11.1) | 9 (7.7) |

| Fat necrosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.6) | 3 (2.6) |

| Benign skin lesion | 3 (13.0) | 8 (20.0) | 5 (9.3) | 16 (13.7) |

| Normal breast tissue | 8 (34.8) | 14 (35.0) | 31 (51.7) | 53 (43.1) |

Overall, the percentage of male patients referred to the South Manchester Breast Unit did not change over the study period: 4.2%, 3.9% and 5.5% for 2018, 2019 and 2020, respectively. These numbers were similar to those seen in the control breast unit in Liverpool: 6.5%, 4.7% and 6.3% for 2018, 2019 and 2020, respectively. Despite the stability in male patient referral patterns, the total percentage of males referred to the South Manchester service with gynaecomastia decreased following implementation of the updated guidelines/introduction of the infographic: 79.6% in 2018 to 62.0% in 2020 (Table 1).

Use of the decision infographic by primary healthcare providers was associated with a decrease in male breast referrals with gynaecomastia (p=0.01). Idiopathic gynaecomastia accounted for the majority (n=114) of cases. Fewer gynaecomastia patients were referred with a benign physiological or drug-related cause (Table 2) after implementation of the infographic (52.2% versus 41.8%). Nonetheless, a large proportion of gynaecomastia referrals had an aetiology that did not necessitate assessment in the tertiary breast clinic (Table 3), both before and after the infographic was implemented: drug-induced (n=96), pubertal (n=18), senile (n=14), endocrinological (n=9), urological (n=2) and alcoholic/liver-related (n=18) gynaecomastia.

Table 2 .

Drugs implicated in gynaecomastia patients

| Drugs | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium channel blocker | 12 | 5 | 3 | 20 |

| Anti-androgens | 9 | 3 | 8 | 20 |

| Anabolic steroids | 8 | 5 | 5 | 18 |

| Statins | 6 | 6 | 6 | 18 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 6 | 4 | 4 | 14 |

| Spironolactone | 5 | 4 | 4 | 13 |

| Recreational drug | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| Anti-psychotic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| HIV medication | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Anti-fungal | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Analgesics | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Chemotherapy | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Digoxin | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Note: some patients were on multiple causative agents.

Table 3 .

Outcomes associated with gynaecomastia referrals

| Number (%) | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total gynaecomastia referrals | 90 | 83 | 98 | 271 |

| Mean (SD) age in years | 51 (23.1) | 45 (20.0) | 47 (21.2) | 48 (21.4) |

| Bilateral | 49 (54.4) | 43 (51.8) | 65 (66.3) | 157 (57.9) |

| Left | 24 (26.7) | 23 (27.7) | 25 (25.5) | 72 (26.6) |

| Right | 17 (18.9) | 17 (20.5) | 8 (8.2) | 42 (15.5) |

| Aetiology of gynaecomastia | ||||

| Drug-induced | 39 (43.3) | 24 (28.9) | 33 (33.7) | 96 (35.4) |

| Pubertal | 5 (5.6) | 9 (10.8) | 4 (4.1) | 18 (6.6) |

| Endocrine | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.8) | 4 (4.1) | 9 (3.3) |

| Urology | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Alcohol or liver disease | 4 (4.4) | 7 (8.4) | 7 (7.1) | 18 (6.6) |

| Senile | 3 (3.3) | 7 (8.4) | 4 (4.1) | 14 (5.2) |

| Idiopathic | 38 (42.2) | 31 (37.3) | 45 (45.9) | 114 (42.2) |

| Total investigations | ||||

| Bloods | 41 (45.6) | 35 (42.2) | 39 (39.8) | 115 (42.4) |

| Ultrasound | 56 (62.2) | 39 (47.0) | 47 (48.0) | 142 (52.4) |

| Mammogram | 37 (41.1) | 33 (39.8) | 42 (42.9) | 112 (41.3) |

| Biopsy | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.1) | 5 (1.8) |

| Nil | 4 (4.4) | 11 (13.3) | 6 (6.1) | 21 (7.7) |

| Treatment | ||||

| Reassure and discharge | 79 (87.8) | 75 (90.4) | 89 (90.9) | 243 (89.7) |

| Onward referral | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.6) | 5 (5.1) | 9 (3.3) |

| Medical treatment | 6 (6.7) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.0) | 9 (3.3) |

| Surgical treatment | 4 (4.4) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.0) | 10 (3.7) |

Nearly half (47.9%) of all gynaecomastia patients with endocrinological, urological, hepatic or unknown aetiology did not have the ABS recommended investigations before referral to the breast clinic. Pre-referral blood tests remained unchanged (51.2% vs 52.6%) after the infographic was introduced in those who would have been recommended them.

In total, 243 (89.7%) patients referred to the breast clinic with gynaecomastia by primary care were reassured and discharged. Nine patients (3.3%) were managed with medical therapy (tamoxifen) and 10 (3.7%) underwent surgical management. An additional 13 (4.8%) patients were denied breast surgical funding by their Clinical Commissioning Group, but these numbers were largely unchanged by the infographic. Five patients required onward referral to another specialism in secondary care in comparison to four patients before implementation of the infographic, but this was not deemed significant owing to the small numbers of patients with endocrinological or urological aetiology.

Non-gynaecomastia-related pathology was also referred to the new breast one-stop clinic. These remaining 123 male patients were referred with a breast lump, breast pain or skin and nipple changes and included breast abscesses (n=5), cysts (n=12), lipoma (n=19), lymphadenopathy (n=9), fat necrosis (n=3), benign skin lesions (n=16), normal breast tissue (n=53), breast cancer (n=2) or other cancers (n=4).

Discussion

Summary

In this study, an infographic was developed to facilitate decision-making and assessment of gynaecomastia patients between primary care and tertiary breast services. Implementation of the infographic into primary care was associated with fewer gynaecomastia referrals to a tertiary breast centre in South Manchester. Although there was a decrease in non-breast-related pathology referred to the breast unit, patients were still referred from regional general practices with benign aetiology, suggesting there exists ongoing disparity between actual clinical practice and recommended national gynaecomastia guidelines for the optimal assessment and management of the condition. Nonetheless, referral practices between general practice and tertiary breast services improved overall following implementation of the infographic into primary care, with more referrals meeting recommended ABS guidelines.

Gynaecomastia cases secondary to medical pathology (eg alcoholic liver disease) or drug use (eg steroids) were referred to the breast clinic, despite recommendations that these patients are best managed in primary care or by medical endocrinology specialists.6 Around half (57.8%) of the gynaecomastia referrals might not have necessitated a tertiary breast assessment based on the clinical or drug history reported.

Few patients with gynaecomastia required surgical intervention for cosmesis or symptomatic relief.4 Only 10 patients underwent definitive breast surgical management during the total study period, although an extra 13 patients had applied and been declined funding for gynaecomastia surgery from their local clinical commissioning group. This is much lower than rates reported in other studies,18,19 although previous studies were published in countries with private healthcare systems or prior to stricter National Health Service funding criteria for the surgical management of gynaecomastia.20

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of the study was the development of a live infographic useable in UK general practice. The novel infographic was informed by a multidisciplinary panel of allied health professionals involved in the management of gynaecomastia in primary and secondary care, and included GPs, breast surgeons and medical endocrinologists. The tool was successfully piloted directly into the clinical setting in primary care consultations and reflected the latest ABS guidelines for the assessment, investigation and best referral pathway for men presenting with gynaecomastia. The infographic was associated with fewer breast referrals to a UK tertiary breast unit, and patients were recruited consecutively reflecting actual point-of-care clinical decision-making in primary and secondary care.

There were limitations as with any empirical research. First, follow-up after implementation of the infographic was limited owing to the coronavirus pandemic. A longer study period had initially been planned to allow more time for the infographic to be established in primary care, but this had to be scaled back after breast clinics were temporarily reduced because of limited hospital capacity in March 2020. Second, data were based on the clinical practices observed in Greater Manchester and may not give a true reflection of national trends elsewhere in the UK. Third, the correlation between gynaecomastia referrals and the infographic could also be attributable in part to other variables not reflected in the data collected. Nonetheless, ABS guidelines are applicable nationally, and the infographic was associated with a positive effect on breast referrals despite the limited follow-up and issues outlined.

Comparison with existing literature

Similar issues related to management of gynaecomastia patients referred to tertiary endocrinology services were observed in another UK regional study,21 where under half (45%) of the underlying causes for gynaecomastia seen in the clinic were unrelated to specialty of referral. Out of 18 gynaecomastia patients with benign aetiology in their study, 15 were subsequently referred for surgical opinion on the NHS and all were discharged without surgical treatment. The infographic developed in this study may help to differentiate patients who require further investigation from those who can be safely reassured in the community.

Screening for underlying pathological conditions in primary care before referral to tertiary breast units may help utilise health resources more effectively. Decision algorithms for the investigation and management of gynaecomastia have been previously described to help differentiate between endocrinological, urological and breast-related disease.22–24 However, none of these studies had implemented the tool directly into clinical practice or assessed its clinical impact.23,4 This study therefore adds to the literature by both developing an updated infographic tool that may be utilised at the point-of-care in general practice and reviewing its potential impact on secondary care services.

Implications for future research and practice

Initial results from this study following implementation of the gynaecomastia infographic in primary care demonstrated fewer referrals to the South Manchester breast clinic, although longer follow-up is required to determine the long-term implications of the infographic on clinical practice.

Further, this study has produced hypothesis-generating data; based on our results, we propose that circulation of the infographic across primary care nationally may raise awareness of updated best practice recommendations and demonstrate an impact on local breast clinic practices that may not have been directly observed during the study period reported. Future research should aim to explore its nationwide adoption through engagement with the Royal College of General Practitioners and NHS England.

Qualitative exploration of the factors influencing gynaecomastia investigation and referral from general practice, alongside prospective feedback on the infographic tool, would be useful to explore why patients are still referred to the breast clinic with benign aetiology (eg drug-induced gynaecomastia) and the process of any recommended investigations undertaken or not undertaken prior to referral. Furthermore, assessment of any long-term clinical and cost implications of the infographic on primary and secondary care is necessary.

In conclusion, implementation of a gynaecomastia infographic in primary care was associated with fewer gynaecomastia referrals to tertiary breast centres. Further research examining the long-term clinical and health economic impact of the infographic tool is required to ascertain whether national implementation will facilitate improved treatment pathways and fewer delays for patients presenting with gynaecomastia in general practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the primary care practices in Greater Manchester who kindly agreed to participate in the piloting of the infographic. Special acknowledgement is also made to Nickwick Papers for assistance with the development and implementation of the referral infographic.

Funding

This research was supported by the Association of Breast Surgery (ABS).

Ethical approval

Governance approval was obtained from Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (Audit ID: 8961).

References

- 1.Thiruchelvam P, Walker JN, Rose Ket al. Gynaecomastia. BMJ 2016; 354: i4833. 10.1136/bmj.i4833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narula HS, Carlson HE. Gynaecomastia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014; 10: 684. 10.1038/nrendo.2014.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenn D, Braunstein M. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 1229–1237. 10.1056/NEJMcp070677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson G. Gynecomastia. Am Fam Physician 2012; 85: 716–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mainiero MB, Lourenco AP, Barke LDet al. ACR appropriateness criteria evaluation of the symptomatic male breast. J Am Coll Radiol 2015; 12: 678–682. 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association of Breast Surgery. Summary Statement on the Investigation and Management of Gynaecomastia in Primary & Secondary Care. UK: Association of Breast Surgery (ABS); 2019. https://associationofbreastsurgery.org.uk/media/345048/breast-surgery-v8.pdf (cited 1 December 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanavadi S, Banerjee D, Monypenny IJ, Mansel RE. The role of tamoxifen in the management of gynaecomastia. Breast 2006; 15: 276–280. 10.1016/j.breast.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan H, Rampaul R, Blamey R. Management of physiological gynaecomastia with tamoxifen. Breast 2004; 13: 61–65. 10.1016/j.breast.2003.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels IR, Layer GT. How should gynaecomastia be managed? ANZ J Surg 2003; 73: 213–216. 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2002.02584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faulkner A, Mills N, Bainton Det al. A systematic review of the effect of primary care-based service innovations on quality and patterns of referral to specialist secondary care. Br J Gen Pract 2003; 53: 878–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowell AJ, Fancey K, Gamble Ket al. Evaluation of a primary to secondary care referral pathway and novel nurse-led one-stop clinic for patients with suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Frontline Gastroenterol 2020; 12: 102–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burdick TE, Kessler RS. Development and use of a clinical decision support tool for behavioral health screening in primary care clinics. Appl Clin inform 2017; 8: 412–429. 10.4338/ACI-2016-04-RA-0068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li DG, Pournamdari AB, Liu KJet al. Evaluation of point-of-care decision support for adult acne treatment by primary care clinicians. JAMA Dermatol 2020; 156: 538–544. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernacchio L, Trudell EK, Hresko MTet al. A quality improvement program to reduce unnecessary referrals for adolescent scoliosis. Pediatrics 2013; 131: e912–e20. 10.1542/peds.2012-2359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steele AW, Eisert S, Witter Jet al. The effect of automated alerts on provider ordering behavior in an outpatient setting. PLoS Med 2005; 2: e255. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Nickwick Papers. The Nickwick Papers, Cornwall, UK. http://www.thenickwickpapers.com/?LMCL=ZNKele. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Researchers. London: Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mett TR, Pfeiler PP, Luketina Ret al. Surgical treatment of gynaecomastia: a standard of care in plastic surgery. Eur J Plast Surg 2020; 43: 389–398. 10.1007/s00238-019-01617-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fruhstorfer B, Malata C. A systematic approach to the surgical treatment of gynaecomastia. Br J Plast Surg 2003; 56: 237–246. 10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00111-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens RJG, Stevens SG, Rusby JE. The ‘postcode lottery’ for the surgical correction of gynaecomastia in NHS England. Int J Surg 2015; 22: 22–27. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asif I, Ayuk J, Gittoes N, Hassan-Smith Z. Management of patients with gynaecomastia in a single centre - a retrospective analysis. Endocrine Abstracts; 2018; 59: P077 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahmani S, Turton P, Shaaban A, Dall B. Overview of gynecomastia in the modern era and the leeds gynaecomastia investigation algorithm. Breast J 2011; 17: 246–255. 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gikas P, Mokbel K. Management of gynaecomastia: an update. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61: 1209–1215. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordova A, Moschella F. Algorithm for clinical evaluation and surgical treatment of gynaecomastia. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008; 61: 41–49. 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]