Abstract

Introduction

Non-injury-related factors have been extensively studied in major trauma and have been shown to have a significant impact on patient outcomes. Mental illness and associated medication use has been proven to have a negative effect on bone health and fracture healing.

Materials and methods

We collated data retrospectively from the records of orthopaedic inpatients in a non-COVID and COVID period. We analysed demographic data, referral and admission numbers, orthopaedic injuries, surgery performed and patient comorbidities, including psychiatric history.

Results

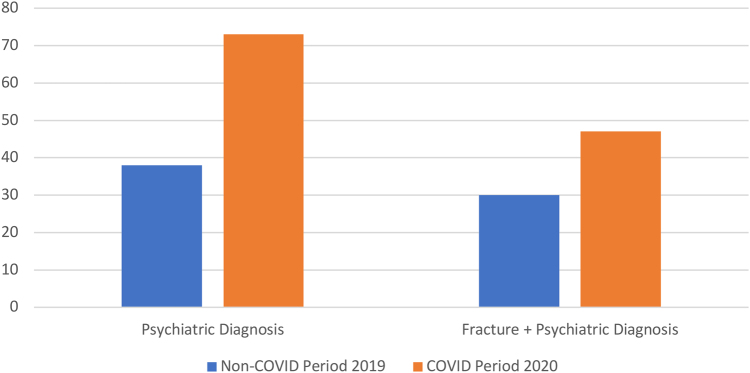

There were 824 orthopaedic referrals and 358 admissions (six/day) in the non-COVID period, with 38/358 (10.6%) admissions having a psychiatric diagnosis and 30/358 (8.4%) also having a fracture. This was compared with 473 referrals and 195 admissions (three/day) in the COVID period, with 73/195 (37.4%) admissions having a documented psychiatric diagnosis and 47/195 (24.1%) having a fracture.

Discussion

There was a reduction in the number of admissions and referrals during the pandemic, but a simultaneous three-fold rise in admissions with a psychiatric diagnosis. The proportion of patients with both a fracture and a psychiatric diagnosis more than doubled and the number of patients presenting due to a traumatic suicide attempt almost tripled.

Conclusion

While total numbers using the orthopaedic service decreased, the impact of the pandemic and lockdown disproportionately affects those with mental health problems, a group already at higher risk of poorer functional outcomes and non-union. It is imperative that adequate support is in place for patients with vulnerable mental health during these periods, particularly as we look towards a potential ‘second wave’ of COVID-19.

Keywords: Bone fractures, Trauma, Mental health, Depression, Pandemic, COVID-19

Introduction

Trauma is the leading cause of mortality in adults under the age of 40 years in the UK and although most orthopaedic major trauma patients survive, many suffer long-term disability.1,2 Non-injury-related factors have been extensively studied in major trauma and have proven to have a significant impact on patient outcomes. Management of major trauma is traditionally based around resuscitation and stabilisation of injuries to restore function and quality of life, with comparatively little attention paid to mental health and its impact on patient recovery and outcomes.1,3 Mental illness and substance use disorders represent a rising global public health problem, with a well-established link between psychiatric and somatic conditions.4,5 The incidence of these disorders in orthopaedics and major trauma has been widely described before, with some studies reporting rates as high as 42%.3,5–7 Additionally, adverse clinical outcomes have been reported in orthopaedic patients with psychiatric illnesses following both emergency and elective surgery ranging from upper and lower limb fractures to total hip and knee arthroplasty and spinal surgery, among other conditions.3,8–11

The Major Trauma Network for England has been in operation since 2012 and is designed to streamline critically injured patients, those sustaining ‘major traumas’, to designated tertiary centres located throughout the country. These major trauma centres were set up so that patients could receive coordinated care from multiple surgical specialties as needed, with a centralisation of expertise, and each generally sees a high volume of patients with significant injuries on a regular basis.

The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic and subsequent nationwide lockdown imposed by the UK government in March 2020 has had a profound impact on society on all fronts.12 The Mental Health Foundation, in collaboration with Universities of Cambridge, Swansea, Strathclyde and Queen’s University Belfast, is currently leading a UK-wide study on the effect of the pandemic on people’s mental health in the form of regular, repeated surveys of over 4,000 adult UK citizens. They report that one in four adults has felt lonely, with an increase from 16% pre-lockdown to 44% post-lockdown in the 18–24 year age cohort.13 An international expert panel led by Professor Holmes and Professor O’Connor has published in Lancet Psychiatry on research priorities, stressing on the importance of publishing high-quality data on the mental health effects of this pandemic.12 We report the epidemiological effect of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health-associated orthopaedic trauma, fractures and admissions to our centre.

Materials and methods

We conducted an observational, retrospective analysis of the orthopaedic inpatients at a London major trauma centre in a non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 period. The former was the eight weeks from 11 September 2019 to 11 November 2019 and the latter was an eight-week period commencing from the first day after lockdown was announced by the UK government encompassing 23 March 2020 to 23 May 2020. Ideally, the non-COVID-19 period would have been from March to May 2019 to provide as closely matched a control cohort as possible; the necessary data from this period were not available for technical and administrative reasons, but the September/November 2019 data were grossly comparable to that of March/May 2019.

We collated data from electronic patient records of all major patients referred to the trauma and orthopaedic service in these two periods. These data comprised demographic data, mechanism of injury, orthopaedic and non-orthopaedic injuries and comorbidities, including psychiatric history (Table 1). Inclusion criteria were: (i) any patients referred to and admitted under trauma and orthopaedics during these periods; (ii) patients with a documented psychiatric diagnosis; (iii) patients with a mechanism of injury that was related to their mental health; (iv) patients with a documented substance and alcohol misuse disorder. Exclusion criteria were: (i) any patients not admitted either solely or under joint care to orthopaedics (referrals are often received from other specialties for current inpatients and such patients were not included, as hospital inpatients would not have been experiencing the effects of lockdown, which is the factor under investigation herein); (ii) patients without any documented psychiatric history, psychiatric mechanism of injury or not on psychotropic drugs.

Table 1 .

Demographic data, number of referrals, admissions, fractures and psychiatric diagnoses

| Demographic | Non-COVID-19 period 2019 | COVID-19 period 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Total referrals (n) | 824 | 473 |

| Total admissions (n) | 358 | 195 |

| Orthopaedic trauma operations (n) | 374 | 210 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis, n (%) | 38/358 (10.6) | 73/195 (37.4) |

| Fracture + psychiatric diagnosis, n (%) | 30/358 (8.4) | 47/195 (24.1) |

| Age (years) | 43.79 | 42.63 |

| Sex (n) | 23 male, 15 female | 40 male, 33 female |

| Previously known to mental health services, n (%) | 22/38 (57.9) | 52/73 (71.2) |

| On psychotropic medication, n (%) | 14/38 (36.8) | 25/73 (34.2) |

Results

In the control period, there were 824 referrals to orthopaedics including patients presenting via major trauma call, which resulted in 358 admissions; 11% (n = 38) of these patients had a psychiatric disorder and 30 had sustained a fracture. Other referrals included joint dislocations (without a fracture), retained foreign bodies and various ‘soft-tissue’ injuries. The most commonly seen psychiatric diagnoses as identified in Table 2 were depression (45%), alcohol excess (24%), anxiety and substance abuse (both 13%). Of particular note, the mechanism of injury for six patients was jumping from height or under a fast-moving vehicle as an act of deliberate self-harm. In total, there were 374 orthopaedic trauma operations performed. The average age of psychiatric patients was 43.79 years, with 23 male and 15 female. Some 22/38 patients were already previously known to local mental health services, with 14/38 already on psychotropic medication at the time of the injury.

Table 2 .

Breakdown of psychiatric diagnoses

| Psychiatric diagnosis | Non-COVID-19 period 2019 (%) | COVID-19 period 2020 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | 45 | 51 |

| Alcohol abuse disorder | 24 | 19 |

| Anxiety | 13 | 21 |

| Drugs abuse disorder | 13 | 16 |

| Schizophrenia | 8 | 12 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 5 | 10 |

| Personality disorder | 11 | 10 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 5 | 0 |

| Other | 8 | 10 |

| Multiple | 32 (n = 12/38) | 38 (n = 28/73) |

From the lockdown (2020) period, there were 473 orthopaedic referrals resulting in 195 admissions; 37% (n = 73) patients had an associated psychiatric disorder, the breakdown of which was similar to the 2019 cohort, and 47 of those had a fracture. Once more in this cohort, 15 patients sustained their injuries in an attempted act of suicide; 210 orthopaedic trauma operations were carried out during this time. The average age of psychiatric patients was 42.63 years, with 40 male and 33 female. Some 52/73 patients were already previously known to local mental health services, with 25/73 already on psychotropic medication at the time of the injury.

Comparison data between the two periods is shown in Figures 1 and 2. The distribution of fractures for both time periods is given in Table 3. There was no significant difference in the mean age for the two groups (p = 0.62).

Figure 1 .

COVID-19 period compared with non-COVID-19 period: summary of referrals, admissions and operations, 2019 and 2020

Figure 2 .

COVID-19 period compared with non-COVID-19 period: summary of psychiatric diagnosis and fracture plus psychiatric diagnosis, 2019 and 2020

Table 3 .

Breakdown of fractures

| Orthopaedic injury | Non-COVID-19 period 2019 | COVID-19 period 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Upper limb | 12 | 15 |

| Lower limb | 24 | 44 |

| Multiple | 3 | 11 |

Discussion

The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown

As one of the major trauma centres for London and the South of England, caring for a population of around 4.5 million people, it is unsurprising that a significant trauma workload continued throughout the lockdown period at our institution. There was a clear reduction in both the number of referrals and thus admissions, as well as the volume of operative cases performed. This is in keeping with figures from other units in the UK.14–15 However, what has not been previously explored is the impact of lockdown on orthopaedic and trauma patients whose injuries are related to mental health conditions. Our data show that during lockdown there was a sharp rise in the number of patients with a mental health condition from 11% to 37% when comparing the two periods. Our figures point to a direct correlation and there have been significant concerns from many sectors about the negative impact of lockdown on the nation’s mental health. Moreover, with unfortunately nearly triple the number of attempted traumatic suicides seen during the lockdown period, there is a clear trend regarding lockdown and an increase in trauma cases related to psychiatric pathology.

The COVID-19 Social Study run by University College London has been evaluating the psychological impact of lockdown since it was first implemented by the UK government.16 Early on, it noted a rise in depression among the general population, which was most pronounced in young people, women and those with a pre-existing mental health condition. By the fifth week of reporting, there was evidence of an increase in suicidal ideation, as well as both thoughts and acts of self-harm. Multiple contributing factors were attributed to these shifts in mood including uncertainty for health and economic wellbeing, feelings of isolation and loneliness and general life dissatisfaction. These findings were further confirmed by Daly et al,17 who noted a substantial rise in mental health problems in general at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic after reviewing data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study ‘Understanding Society’.17 They found that 37% of participants reported a mental health problem, which was a statistically significant increase from pre-lockdown times.

Challenges for orthopaedic trauma services

During the initial months of the pandemic, it was common for most hospitals in the UK to ‘redeploy’ staff to high-demand areas such as intensive care and respiratory or general medicine. The British Orthopaedic Association identified that as elective surgery was cancelled, many orthopaedic junior doctors were redeployed, which then placed further strain on the remaining surgical workforce.18 Redeployment has had other consequences as well: physical operating theatres and many members of the anaesthetic department were repurposed to care for patients with COVID-19 as extra capacity for overburdened intensive treatment units. This, in turn, meant that the demand for time in theatre was still significantly greater than what was available. While overall trauma case numbers have generally fallen, so too has the availability of anaesthetists and operating theatres. Unfortunately, the potentially avoidable increase in presentations stemming from mental health problems is stretching a system that is already under enormous strain.

Another stressor to surgical services in the UK is the additional precautions required to safely anaesthetise and operate on patients with orthopaedic conditions. Many commonly used techniques and instruments required for orthopaedic surgery such as bone-sawing, reaming, pulse lavage and electrocautery are believed to be ‘aerosol-generating procedures’.19 Recommendations as to how to minimise these risks include using enhanced personal protective equipment and deep-cleaning in theatre and this often means that fewer operative cases are performed due to delays. While these delays will lessen as such practices becomes more routine, it once again means that theatre time is at an absolute premium.

The combination of a depleted workforce, prolonged turnaround times in theatre and reduced availability of trauma operating lists means that the waiting time for non-elective surgery is increasing even for cases that need to be treated as a priority such as neck of femur and open fractures. If more can be done to support patients with psychiatric comorbidities, it stands to reason that some of these self-inflicted injuries could be avoided and so too could the pressures they place on orthopaedic services.

From the COVID-19 cohort, 35 patients with psychiatric comorbidities required a trauma operation. It is impossible to accurately say how many other cases could have been performed if these procedures were not needed, but as during the peak of the pandemic saw days with only two or three cases being performed due to altered anaesthetic protocols and deep-cleaning delays between cases, this clearly represents a significant volume of work. The issue of resource allocation is all the more important as we move into the post-lockdown era, as there is a resurgence in the commonly seen injuries from sporting, recreational and intoxication-related activities that had previously been banned.

Future mental health support

While the significance of our findings stand alone, their salience is even more apparent when it comes to the second wave of COVID-19. Following a further spike in COVID-19 cases, the UK has once more gone into lockdown. Accordingly, one would expect the previous negative consequences for those with mental health conditions to resurface and it is important that measures are put in place to try and counteract this situation as best as possible. Additionally, for those individuals who have already experienced a traumatic orthopaedic injury during the first lockdown, the prospect of a repeat is bound to be all the more harrowing. The literature shows that such patients are liable to be doubly affected by this as they would potentially experience both problems with their mental health, as well as poorer physical health outcomes if they do sustain a traumatic injury. Falsgraf et al reported on a retrospective analysis of 25,000 patients with trauma and identified that those with pre-existing psychiatric comorbidities had a significantly longer total length of stay (10.6 days vs 6.2 days; p < 0.001) and higher rate of postoperative complications (adjusted odds ratio 1.9; p < 0.001).20

Looking to the future, the need for better mental health provisions during periods of crisis and lockdown is becoming ever clearer. At a population level, this is a well-established problem: in 2018 NHS England released the ‘Five year forward view for mental health’ and noted a significant increase in the demand for mental health services that the current system was already struggling to meet, even without the increased strain from lockdown.21 Specifically for patients with major trauma, more needs to be done to provide post-injury support as recognised by various studies.22–23 while there is currently no firm National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations for planned counselling for trauma patients, we believe that the benefits are self-evident, and there are multiple references to the usefulness of psychological input throughout UK trauma guidelines including the NICE guideline NG40 Major Trauma: Service Delivery and the forthcoming guideline on rehabilitation after traumatic injury.24,25 Given what is already known about the risks of psychological sequelae following hospitalisation for a traumatic injury, we suggest that further research is conducted into the potential benefits of routine psychological support for these patients.

Mental health disorders, bone health and fracture healing

It is well established that patients with psychiatric diagnoses often have poorer functional outcomes following orthopaedic surgery, but a less frequently considered phenomenon is the physiological effects of psychiatric comorbidities and the potential adverse effects that can occur with prolonged use of psychotropic medications. In 2016, Rosenblat et al published a comprehensive review showing an increased incidence in fractures and decreased bone mineral density in patients with major depressive disorder due to a multifactorial cause.26 They postulated that while there were behavioural elements at play (smoking, alcohol intake and relatively lower activity levels), various neuroendocrine pathways including heightened levels of inflammatory mediators and excessive activation of the cortisol system were also responsible for the overall reduction in bone strength. A further meta-analysis by Wu et al quantitatively demonstrated this and found that patients with depression were at a 39% higher risk of sustaining a fracture.27 As we know that patients with mental health conditions are more at risk of requiring input from an orthopaedic surgeon, it would stand to reason that taking action to prevent these injuries from happening in the first place would be a beneficial measure.

Given the above links between poorer overall bone health and psychiatric conditions, it is not surprising to learn that there is also a higher incidence of non-union following a fracture. Basic science research by Nie et al identified a molecular pathway of reduced bone healing secondary to low osteoblast differentiation in rats with an induced depressive state.4 The literature further supports this including Harkin et al’s analysis of factors affecting non-union of humeral factors.28 They found a statistically significant correlation with various psychiatric diagnoses. Similarly, a team from Duke University in North Carolina found higher rates of delayed union of metatarsal fractures for patients who suffer from any form of psychosis.29 The negative effects of non-union are well chronicled and can include not only a significant reduction in overall quality of life, but also have major cost implications in the form of further hospitalisations and in many cases repeated surgery. The higher rates of delayed and non-union for patients with mental health diagnoses represents both a disadvantage to the individual and also to wider healthcare services at a time when both mental health and surgical services are facing unprecedented demand, this is a complication that should be avoided.30

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrated that even during lockdown a robust orthopaedic and trauma service was needed. Regrettably, there was a sharp rise in the number of patients with mental health problems during this time period and a significant increase in presentations due to suicide attempts and acts of self-harm. Further research is required to continue to evaluate the interplay between mental health, trauma and its long-term consequences (both physical and mental), and specifically with regard to the effect on bone healing. It is becoming more apparent that a correlation exists between poor orthopaedic outcomes and patients with psychiatric comorbidities, and the real challenge is what can be done to improve this, but hopefully this paper highlights issues for a second COVID-19 wave and future pandemics.

References

- 1.Bhandari M, Busse JW, Hanson BPet al. Psychological distress and quality of life after orthopaedic trauma: an observational study. Can J Surg 2008; 51: 15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS England. More than 1,600 extra trauma victims alive today says major new study [press release]. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2018/08/more-than-1600-extra-trauma-victims-alive-today-says-major-new-study (cited November 2020).

- 3.Simske NM, Audet MA, Kim CYet al. Mental illness is associated with more pain and worse functional outcomes after ankle fracture. OTA Int 2019; 2: e037. 10.1097/OI9.0000000000000037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nie C, Wang Z, Liu X. The effect of depression on fracture healing and osteoblast differentiation in rats. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018; 14: 1705–1713. 10.2147/NDT.S168653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman REet al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001547. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muscatelli S, Spurr H, O’Hara Net al. Prevalence of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder after acute orthopaedic trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2017; 31: 47–55. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg D, Narayanan A, Boden Ket al. Psychiatric illness is common among patients with orthopaedic polytrauma and is linked with poor outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98: 341–348. 10.2106/JBJS.15.00751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavernia C, Alceroo J, Brooks Let al. Mental health and outcomes in primary total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27: 1276–1282. 10.1016/j.arth.2011.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singleton N, Poutawera V.. Does preoperative mental health affect length of hospital stay and functional outcomes following arthroplasty surgery? A registry-based cohort study. J Orthopaedic Surg 2017; 25: 1–9. 10.1177/2309499017718902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trief PM, Ploutz-Snyder R, Fredrickson BE. Emotional health predicts pain and function after fusion: a prospective multicentre study. Spine 2006; 31: 823–830. 10.1097/01.brs.0000206362.03950.5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips AC, Upton J, Duggal NA. Depression following hip fracture is associated with increased physical frailty in older adults: the role of the cortisol: dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate ratio. BMC Geriatr 2013; 13: 60. 10.1186/1471-2318-13-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VHet al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: 547–560. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mental Health Foundation. The COVID-19 Pandemic, Financial Inequality and Mental Health. London: Mental Health foundation; 2020. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/our-work/research/coronavirus-mental-health-pandemic/covid-19-inequality-briefing (cited November 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott CEH, Holland G, Powell-Bowns MFRet al. Population mobility and adult orthopaedic trauma services during the COVID-19 pandemic: fragility fracture provision remains a priority. Bone Joint Open 2020; 1: 182–189. 10.1302/2633-1462.16.BJO-2020-0043.R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hampton M, Clark M, Baxter Iet al. The effects of a UK lockdown on orthopaedic trauma admissions and surgical cases. Bone Joint Open 2020; 1: doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.15.BJO-2020-0028.R1. 10.1302/2633-1462.15.BJO-2020-0028.R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.University College London. COVID-19 Social Study: Understanding the psychological and social impact of the pandemic. https://www.covidsocialstudy.org (cited November 2020).

- 17.Daly M, Sutin A, Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study [preprint]. Psychol Med PsyArXiv 2020; doi: 10.31234/osf.io/qd5z7. 10.31234/osf.io/qd5z7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins P. The Early Effect of COVID-19 on Trauma and Elective Orthopaedic Surgery. British Orthopaedic Association. https://www.boa.ac.uk/policy-engagement/journal-of-trauma-orthopaedics/journal-of-trauma-orthopaedics-and-coronavirus/the-early-effect-of-covid-19-on-trauma-and-elect.html (cited November 2020).

- 19.Raghavan R, Middleton PR, Mehdi A. Minimising aerosol generation during orthopaedic surgical procedures- Current practice to protect theatre staff during Covid-19 pandemic. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020; 11: 506–507. 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falsgraf E, Inaba K, Roulet ADet al. Outcomes after traumatic injury in patients with preexisting psychiatric illness. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017; 83: 882–887. 10.1097/TA.0000000000001588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS Providers. Mental health services: key points. https://nhsproviders.org/mental-health-services-addressing-the-care-deficit/key-points (cited November 2020).

- 22.Shih RA, Schell TL, Belzberg H. Prevalence of PTSD and major depression following trauma-centre hospitalization. J Trauma 2010; 69: 1560–1566. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e59c05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans CCD, DeWit Y, Hall S. Mental health outcomes after major trauma in Ontario: a population-based analysis. CMAJ 2018; 190: E1319–E1327. 10.1503/cmaj.180368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Major Trauma: Service delivery. NICE Guideline NG40. London: NICE; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Rehabilitation After Traumatic Injury. (GID-NG10105). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ng10105 (cited November 2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenblat JD, Gregory JM, Carvalho AF, McIntyre RS. Depression and disturbed bone metabolism: a narrative review of the epidemiological findings and postulated mechanisms. Curr Mol Med 2016; 16: 165–178. 10.2174/1566524016666160126144303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Q, Liu B, Tonmoy S. Depression and risk of fracture and bone loss: an updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Osteoporos Int 2018; 29: 1303–1312. 10.1007/s00198-018-4420-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harkin FE, Large RJ. Humeral shaft fractures: union outcomes in a large cohort. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2017; 26: 1881–1888. 10.1016/j.jse.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson R, Parekh S, Braid-Forbes MJ, Steen RG. Delayed healing in metatarsal fractures: role of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound treatment. J Foot Ankle Surg 2019; 58: 1145–1151. 10.1053/j.jfas.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hak DJ, Fitzpatrick D, Bishop JAet al. Delayed union and nonunions: epidemiology, clinical issues, and financial aspects. Injury 2014; 45: S3–7. 10.1016/j.injury.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]