Abstract

The objectives were: (a) to establish cannabis use prevalence in university students; (b) to determine the changes in consumption of cannabis between prior to and during lockdown. Problematic consumption, gender, and age were taken into account to establish risk groups. Of 1,472 participants between 18-54 years (M = 27.51), 8.01% reported using cannabis before and/or during lockdown (56.6% male). The Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST) was used to detect cannabis abuse. The main form of consumption was spliffs (89.9%). The mean of spliffs consumed per day decreased during lockdown, but was only significant in male and in the 18-24 group. This decrease was also significant for all three levels of CAST problematic use. Users with moderate addiction and dependence reduced their average number of spliffs consumed per day during lockdown to a greater extent than those without addiction. These findings establish target groups of prevention interventions in the university.

Keywords: Cannabis, University students, Adults, Addiction, COVID-19 lockdown

Among other measures, lockdown and social distancing strategies for the containment of COVID-19 entailed the suspension of face-to-face teaching activity in universities, transferring all teaching to an online format (García-Peñalvo et al., 2020). This event could have led to a change in the patterns of cannabis use in the university population, which has a particularly high prevalence, ranging from 39.2 to 50.6% who have consumed in the last year, 21.6–30.2% in the last month, and 15.9–18.4% who consumed on a daily basis (Arias-de la Torre et al., 2019; Villanueva et al., 2021).

Traditionally, the university stage coincides with a transition period that presents specific risk factors, such as the process of independence from the family nucleus (Arias-De la Torre et al., 2019) and new experiences and forms of fun (Abar & Maggs, 2010; Tirado et al., 2010; Páramo et al., 2020). Furthermore, drug use increases especially in university students who live in dorms or student flats, although the preferred place of consumption is at private parties (Higuero, 2018) and certain festive events (Buckner et al., 2018). In fact, the majority of the university population considers cannabis a very accessible substance (Alvarez-Roldan et al., 2022).

The measures used to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic have caused multiple changes in the university student population in terms of life planning, social interaction, and exposure to unusual psychosocial stressors. Furthermore, the literature highlights university students to be a population vulnerable to stress (Glodosky & Cuttler, 2020; Zenebe & Necho, 2019), with stress being the most reported reason for cannabis use due to its palliative effects on anxiety (Glodosky & Cuttler, 2020; Hser et al., 2017).

However, the reality of university students is heterogeneous, and therefore so is their relationship with cannabis (Hernandez-Serrano et al., 2018). It brings together people within a wide range of ages, some of whom must balance their studies with professional work or family (Dutton et al., 2002). Taking this into account, and considering the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on mental health in the population worldwide, relevant questions remain to be answered (Huang & Zhao, 2020; Shigemura et al., 2020; Torales et al., 2020). For example, what is the prevalence and type of cannabis use in the adult population that combines university studies with work and family responsibilities? This topic is not addressed in studies conducted with university students, so it becomes an invisible part of cannabis use reality in the university context, even though it should be taken into account within the preventive actions that are framed within Healthy Campuses. Another question that underlies the impact of the COVID-19 measures is whether or not the non-attendance and restriction of festive events traditionally associated with the university context are environmental factors that are sufficiently determining to generate changes in the pattern of cannabis use. Or if these possible changes can be differentiated according to gender.

For all these reasons, the objectives of this study were as follows: (a) to establish cannabis user prevalence in university students; (b) to determine the changes in the pattern of consumption of cannabis and derivatives between the period prior to and during lockdown. For both objectives, problematic consumption, gender, and age were taken into account to establish risk groups.

Method

Design

This study is descriptive and non-probabilistic, and it uses convenience sampling. A battery of online surveys was used to collect and evaluate the variables under study. Age ranges were established based on those that showed adequate Internet access, as stated in the Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies at Home Survey (INE, 2019).

Participants

Of the initial sample of participants (n = 4213), 434 (10.3%) were eliminated due to missing values, inconsistent response patterns, or being outside the established age range (18–64 years). The final sample was made up of 3779 participants, of which 1472 were university students (58% female; 42% male), aged between 18 and 64 years (M = 31.59 and SD = 09.37), corresponding to the 17 Spanish autonomous communities and two autonomous cities.

Instruments

Sociodemographic variables were collected: gender (male or female); age, according to the age ranges established by the EDADES survey (OEDA, 2020) (18–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years).

To analyze cannabis use, several measures were considered:

The measurement of days of consumption per month during the last 6 months was used to obtain a representative frequency of consumption before the pandemic, using the alternatives of the EDADES survey (OEDA, 2020) for consumption in the last 30 days. Likewise, consumption in the last 7 days (from 0 to 7 days) was used to establish the frequency of weekly consumption during lockdown. In both cases, questions were asked about the cannabis (marijuana and/or hashish), CBD, and synthetic cannabis consumption.

The average amount of consumption per day before the pandemic and during lockdown, regarding the consumption of the following: (a) spliff (cannabis mixed with tobacco); (b) joint (cannabis cigarette); (c) cannabis mixed with hashish; (d) CBD oil; (e) synthetic cannabis.

The number of spliffs obtained with 1 g of marijuana and with 1 g of hashish.

Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST) (Legleye et al., 2007), in its translated version and validated into Spanish (Klempova et al., 2009). It consists of six items that allow detecting patterns of cannabis abuse based on the frequency of experiencing each of the problems described. Given that it offers more information and presents better criterion validity than the binary version, the Likert-type response format was used (0 “never,” 1 “rarely,” 2 “sometimes,” 3 “quite often,” and 4 “very often”), providing a range from 0 to 24 points (Cuenca-Royo et al., 2012). The cutoff points for CAST reported in the study by Cuenca-Royo et al. (2012) were 7 for moderate addiction (DSM-5) and 9 for dependence (DSM-IV).

Procedure

Data collection started on April 14th, 2020, after the first 30 days of confinement measures, and it ended on May 29th, when the de-escalation measures started. The data collection strategy was based on a survey hosted on a web, posts on social media, and advertisements via e-mail and smartphone messaging applications. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary, in accordance to the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, of Personal Data Protection and Digital Rights Guarantee. They were asked to give their consent to participate. Selection criteria were as follows: (a) age between 18 and 64; (b) explicit agreement to participate; and (c) properly filling out the survey. The study was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and approved by the Committee of Evaluation and Follow-up of Research with Human Beings (CEISH) from the Valencian International University (protocol code CEID2020_02).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). First, an analysis of the frequency of cannabis use before the pandemic and during the COVID-19 lockdown was carried out. To analyze the differences in the average cannabis consumption before and during lockdown, Student’s t-test was applied for each of the consumption modalities. Subsequently, the average daily consumption of the cannabis mixture before and during the lockdown was compared according to gender and age. In all cases, compliance with the assumptions of normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) and homoscedasticity (Levene’s test for equality of variances) was verified first.

Additionally, several analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed to study the effect of the interaction between the average consumption before and during lockdown and gender and age.

Finally, given that smoking spliff was the main form of consumption, the spliff consumption pattern was analyzed before the pandemic and during the COVID-19 lockdown using the CAST scores to evaluate patterns of problematic cannabis consumption (no addiction (− 4), problematic consumption (> 4), moderate addiction (+ 7), and dependence (+ 9). Specifically, Student’s t-test for related samples was used to analyze differences in mean daily consumption before and during lockdown for each of the groups and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to verify the existence of differences between the groups (no addiction, moderate addiction, and dependence), using Bonferroni for the post hoc tests.

To calculate the effect size of all the differences found, Cohen’s d was used.

Results

A total of 8.01% of university students (n = 118) admitted having used cannabis before the pandemic or during lockdown, being 56.6% male (n = 67) and 43.4% female (n = 51), with a mean age of 27.51 (SD = 6.09). The main form of consumption was by smoking spliffs (89.9%), followed by joint (7%), and CBD (3.2%). Of these 118 consumers, 31.3% (n = 37) reported an average monthly frequency of consumption of 20 days or more in the last 6 months prior to the pandemic. Regarding consumption during the last 7 days during lockdown, 22.2% (n = 26) consumed every day.

Among cannabis users, 79.66% (n = 94; female = 40; male = 54) had used nicotine in the last 6 months, reporting consumption of 20 days or more by 53.4% (n = 63; female = 26; male = 37). Regarding consumption during the last 7 days during lockdown, 61.01% (n = 72) used nicotine, and 46.6% (n = 55; female = 25; male = 30) reported daily consumption. Table 1 and Fig. 1 show the distribution of the sample according to the level of problematic cannabis use (CAST), according to gender and age.

Table 1.

Distribution of the sample according to problematic consumption (CAST), according to gender and age

| Global (%, n) | Gender (%, n) | Age (%, n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | 18–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | ||

| No addiction | 43.7 (52) | 58.3 (30) | 32.5 (22) | 40.8 (16) | 44.3 (19) | 48.5 (11) | 50 (5) | 0 |

| Moderate addiction | 46.8 (55) | 36.1 (19) | 55 (37) | 47.4 (19) | 44.3 (19) | 44.3 (10) | 50 (5) | 100 (2) |

| Dependence | 9.5 (11) | 5.6 (3) | 12.5 (8) | 11.8 (5) | 11.3 (5) | 7.2 (2) | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 1.

Mean CAST score during the COVID-19 lockdown according to gender and age

When analyzing the differences in the consumption patterns before and during lockdown, differences were only observed in the average number of spliffs consumed per day, observing a decrease during lockdown (Mbefore = 1.23; SD = 1.58; Mduring = 0.90; SD = 1.76, t(116) = 2.223, p < 0.05, d = − 0.197) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean cannabis use per day before the COVID-19 pandemic and during lockdown

| Before lockdown M (SD) |

During lockdown M (SD) |

t | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spliff | 1.23 (1.58) | 0.90 (1.76) | 2.223 | 0.028 | −0.222 |

| Joint | 0.09 (0.35) | 0.18 (0.58) | −1.772 | 0.079 | |

| Cannabis mixed with hashish | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.03 (0.25) | −0.533 | 0.595 | |

| Oil (CBD) | 0.04 (0.22) | 0.06 (0.29) | −0.801 | 0.425 | |

| Synthetic cannabis | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| Spliffs with 1 g of marijuana | 2.98 (3.64) | 2.56 (4.03) | 1.489 | 0.139 | |

| Spliffs with 1 g of hashish | 2.70 (4.82) | 2.67 (5.16) | 0.102 | 0.919 |

N = 118; t, Student’s t; p, significance level; d, Cohen’s d

Considering the gender variable, male university students consumed fewer spliffs on average per day during lockdown (M = 1.08; SD = 2.033) than before the pandemic (M = 1.55; SD = 1.86) (t(66) = 2123; p < 0.05; d = − 0.27), with no statistically significant differences in university female during lockdown (M = 0.68; SD = 1.313) compared to before the pandemic (M = 0.81; SD = 1.005) (t(50) = 0.769; p = 0.446) (Table 3; Fig. 2). Additionally, differences are observed in the mean number of spliffs consumed per day between male (M = 1.55; SD = 1.86) and female (M = 0.81; SD = 1) before the pandemic (t(105.607) = − 2.789; p < 0.01; d = 0.488), but not during lockdown (t(116) = − 1.210; p = 0.229). No statistically significant differences were found in the interaction of daily spliff consumption before the pandemic and during lockdown according to gender (F(1.110) = 1.521; p = 0.220).

Table 3.

Average number of spliffs consumed per day before the pandemic and during lockdown, according to gender, age, and level of problematic use (CAST)

| n | Before lockdown M (SD) |

During lockdown M (SD) |

t/Z | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 51 | 0.81(1.005) | 0.68 (1.313) | 0.769 | 0.446 | |

| Male | 67 | 1.55 (1.857) | 1.08 (2.033) | 2.123 | 0.05 | −0.27 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 40 | 1.36 (1.680) | 0.56 (1.014) | 2.987 | 0.01 | −0.401 |

| 25–29 | 42 | 1.11 (1.312) | 0.98 (1.654) | 0.677 | 0.502 | ||

| 30–34 | 1.34 (1.857) | 1.26 (2.583) | 0.212 | 0.834 | |||

| 35–44 | 11 | 0.41 (0.518) | 0.50 (1.629) | −0.161 | 0.876 | ||

| 45–54 | 2 | 3.51 (3.004) | 3.51 (3.004) | - | - | ||

| Problematic use (CAST) | NA | 52 | 0.4 (0.834) | 0.07 (0.387) | 2.517 | 0.05 | −0.274 |

| MA | 55 | 1.82 (1.696) | 0.27 (0.719) | 5.907 | 0.001 | −0.598 | |

| DP | 11 | 2.13 (1941) | 0.21 (0.429) | 2.883 | 0.05 | −0.553 |

NA, no addiction; MA, moderate addiction; DP, dependency; t, Student’s t; Z, Wilcoxon; p, significance level; d,Cohen’s d

Fig. 2.

Average number of spliffs consumed per day before the COVID-19 pandemic and during lockdown according to gender

Considering the age variable, only the group of students from 18 to 24 years old showed a significant decrease in daily spliff consumption during lockdown (M = 1.36; SD = 1.680) compared to consumption before the pandemic (M = 0.56; SD = 1.014) (t(39) = 2987; p < 0.01 ; d = − 0.401) (Table 3; Fig. 3). No statistically significant differences were found in the interaction of daily spliff consumption before the pandemic and during lockdown according to age (F(4.107) = 1.568; p = 0.188).

Fig. 3.

Average number of spliffs consumed per day before the COVID-19 pandemic and during lockdown according to age

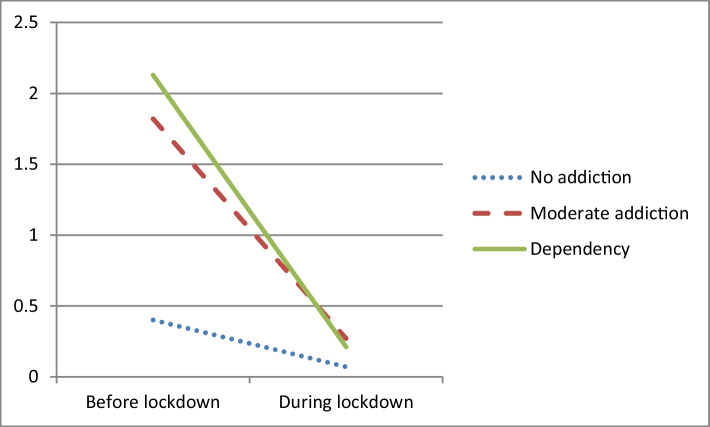

Based on the level of problematic cannabis use, a significant decrease in the mean number of spliffs consumed per day during lockdown is observed in university students who do not present an addiction (Mbefore = 0.4; SD = 0.834; Mduring = 0.07; SD = 0.387; t(51) = 2.517; p < 0.05; d = − 0.274), those with moderate addiction (Mbefore = 1.82; SD = 1.696; Mduring = 0.27; SD = 0.719; t(54) = 5.907, p < 0.001, d = − 0.598); and in those with cannabis dependence (Mbefore = 2.13; SD = 1.941; Mduring = 0.21; SD = 0.429; t(10) = 2.883; p < 0.05; d = − 0.553) (Table 3; Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Average number of spliffs consumed per day before the COVID-19 pandemic and during lockdown according to problematic use (CAST)

The ANOVA revealed significant differences between the three groups of problematic cannabis use in their decreased consumption during lockdown (F(2.149) = 19.315; p = 0.001). Post hoc analyses indicated that the group of university students with moderate addiction and the group with cannabis dependence reduced their mean number of spliffs consumed per day during lockdown to a greater extent than those without addiction, whose decrease was smaller (p < 0.05). However, the average number of spliffs consumed per day before the pandemic in the group that does not present addiction was lower compared to the other two groups that presented a pattern of problematic consumption (F(2.115 ) = 16.056; p = 0.001).

Discussion

The present study provides relevant information regarding cannabis use in the university population between 18 and 54 years of age, and the changes in the consumption pattern before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the lockdown period. These findings offer a relevant gender perspective and new insight regarding the adult university population, avoiding the limitations of other studies with samples of only undergraduate students (approximately between the ages of 18 and 25). They also make it possible to establish groups that are more likely to develop problematic cannabis use and become the target of prevention interventions, early detection, and brief counseling in the university environment.

The results indicate that only one in 10 university students had used cannabis before the pandemic or during the COVID-19 lockdown. Of these, only a third did it daily or almost daily before the pandemic and approximately a fifth did so with that frequency during lockdown. Therefore, we can state that the measures against COVID-19 decreased the daily cannabis user prevalence in university students, data that are in line with those found in the Spanish population by Balluerka et al. (2020).

Regarding age, one of the novelties of this study has been to consider the university population aged over 30 years. Cannabis-using university students aged 30 years or older represent 30.1% of the total sample of university students in this study. The analysis revealed that as the age range increased, problematic use of cannabis became less, the average number of spliffs consumed daily also being less, with the exception of the age range of 30–34. The highest prevalence of cannabis use is found in university students between the ages of 18 and 29, followed by 30–34. These same ages show a higher prevalence of consumers with moderate addiction and dependence. These data are in line with what was reported by the European Observatory for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA, 2020) and the Spanish Observatory on Drugs and Addictions (OEDA, 2021) regarding cannabis use in the adult population.

Spliffs are the preferred form of consumption, being the usual in the Spanish and European population (EMCDDA, 2019; Pirona et al., 2015) and university population (Alvarez-Roldan et al., 2022). This has important implications. Dual cannabis-tobacco use has worse consequences both at the addiction level and in terms of its associated physical and mental health problems (Davis et al., 2019; Tucker et al., 2019). It is also related to the failure in the quitting process, with interventions to stop consumption aimed at both substances at the same time being more effective (Rogers et al., 2020; Walsh et al., 2020).

With regard to the above, the average number of spliffs obtained with 1 g of cannabis before and during lockdown did not change. In other words, an effect of stretching the substance is not observed by increasing the amount of tobacco and decreasing the amount of cannabis in each spliff. So we can establish that the COVID-19 measures only affected the pattern of spliff consumption, decreasing the average daily amount but not altering the percentages of cannabis-tobacco mixture, at least in the university population participating in this study.

The relationship between both substances goes beyond concurrent use. In the sample of participating university students, eight out of 10 cannabis users had used nicotine products in the 6 months prior to the pandemic, and six out of 10 during lockdown. In short, there is a clear relationship between cannabis and tobacco use, consistent with current literature (Jayakumar et al., 2021; Wilhelm et al., 2020).

Based on the analysis of the results according to gender, the prevalence of male university students who use cannabis (10.82%) doubles that of female university users (5.98%). This data is in line with prevalence studies in Spain (EMCDDA, 2020), although there is evidence that females have been increasing their consumption in recent years (Greaves & Hemsing, 2020). In this sense, it is convenient to explore sociocultural factors that can explain this gender difference. Rodriguez et al. (2019) point out that drug use is a practice associated with the stereotype of masculinity, defined by the search for sensations, the need to show strength, and the absence of weakness. In addition, female present a higher risk perception regarding cannabis use (Grevenstein et al., 2015).

The prevalence of male with moderate addiction (55%) was observed to be higher than that of female (36.1%), and dependency was double (5.6% female; 12.5% male). This finding is related to the average number of spliffs consumed per day before the pandemic and during lockdown, being higher in male (Mbefore 1.55; Mduring 1.08) than in female (Mbefore 0.81; Mduring 0.68). From these data, one could assume that the male group should be a priority in policies aimed at the prevention and care of cannabis use in the university environment. However, one must consider that the endogenous cannabinoid receptor system is sexually dimorphic (Hart-Hargrove & Dow-Edwards, 2012), making female more sensitive to the adverse effects of cannabis at the brain level (Wiers et al., 2016). This implies a more rapid dependence on cannabis than in male and worse withdrawal symptoms (Hernández-Avila et al., 2004). Consequently, despite the higher prevalence of cannabis users in university male than in university female, both groups require consideration as target groups for health policies in both face-to-face and online university campuses.

The impact of the COVID-19 measures has shown differential effects based on gender. While male’s average number of spliffs per day decreases significantly during lockdown from 1.55 to 1.08, females show a non-significant decrease from 0.81 to 0.68 spliffs per day. In fact, significant differences were observed in the average number of spliffs consumed per day between male and female before the pandemic, but not during lockdown. It is worth asking whether the underlying causes of this finding are related to psychosocial stressors linked to a greater difficulty in reconciling work and family, which during lockdown affected female and male differently.

Likewise, the measures against COVID-19 favored the decrease in the average consumption of spliffs per day in the group of 18–24 years, being the only age group in which it decreased significantly. This may be due to the fact that younger university students, who study in person, tend to consume substances for social reasons (Grant et al., 2007), and preferably at private parties (Higuero, 2018) and certain festive events (Buckner et al., 2018). Lockdown and restrictions on social contact drastically reduced the contexts of shared consumption, such as parties and other usual events in the university environment.

Regarding the problematic use of cannabis (CAST), it is clearly observed that the greater the problematic use, the greater the average number of spliffs consumed per day before and during lockdown. Likewise, it is clearly reflected in the data that the measures applied against COVID-19 led to a significant decrease in the average number of spliffs consumed per day among all consumers. However, among those with problematic use (both moderate addiction and dependence), the effect size of this decrease was greater than among non-problematic users. This finding has important health implications, given that it is regular or daily consumption that is associated with the majority of harmful effects (Fischer et al., 2017). In other words, the lockdown situation, far from generating greater cannabis use, associated with the anxiety and stress of the situation, promoted a decrease in the average number of spliffs consumed. This fact may be influenced by other contextual variables associated with the availability, accessibility, and price of the substance (Groshkova et al., 2020). In any case, this finding points to environmental prevention measures as key strategies in cannabis demand reduction policies. This is especially relevant in the global context of the debate on the legal status of cannabis and its liberalization for recreational use.

The findings presented in this study reveal the differences in cannabis use in the university population according to gender and age. It seems of interest to analyze the consumption reasons according to both variables. Previous studies (Alvarez-Roldan et al., 2022) indicate that among university cannabis users were highlighted as main reasons for consumption a number of positive effects based on their personal experience, such as that they like the flavor, they feel great, makes them laugh, take it to cheer up and have a good time, relaxes them, calms their anxiety, helps them fall asleep, facilitates introspection, and allows them to escape and disconnect. Perhaps certain reasons are more present in one gender than the other, or in an age range, allowing to guide preventive interventions to approach these motivations for cannabis use.

This work has several limitations. Although the sample with which the study was carried out is large, it is a convenience sample, without random selection or stratified sampling, so it is not possible to generalize the results obtained beyond this study. Furthermore, this fact is especially relevant if one considers that when speaking of the university population, the literature usually refers to young people between 18 and 30 years of age, and almost half of the sample is older. However, the novelty of this study lies precisely in the inclusion of this invisible university group in studies on cannabis use. This study did not distinguish between users with and without self-cultivation. Future studies could explicitly address the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on cannabis use in self-cultivators, a process by which they have greater accessibility to the substance (Isorna et al., 2016; Amado et al., 2020). It is important to point out that the pattern of dual consumption of cannabis-tobacco (spliffs) is widely extended in Spain and Europe compared to other geographies, such as the American continent, where cannabis consumption is mostly consumed by itself, without mixing it with another substance. Therefore, these findings are sensitive to geographic/cultural context. Likewise, it would be relevant to have longitudinal data to establish whether the changes produced in relation to problematic cannabis use persist over time.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by Valencian International University (PII2020_05).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), and was approved by the Committee of Evaluation and Follow-up of Research with Human Beings (CEISH) from Valencian International University (VIU) (protocol code CEID2020_02).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: The surname of co-author Vicente Andreu-Fernández was incorrectly given (as “Fernández”) in this article as originally published.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/31/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s11469-023-01047-5

Contributor Information

Víctor José Villanueva-Blasco, Email: vjvillanueva@universidadviu.com.

Verónica Villanueva-Silvestre, Email: vvillanueva@universidadviu.com.

Andrea Vázquez-Martínez, Email: avazquezm@universidadviu.com.

Vicente Andreu-Fernández, Email: vandreu@universidadviu.com.

Manuel Isorna Folgar, Email: isorna.catoira@uvigo.es.

References

- Abar CC, Maggs JL. Social influence and selection processes as predictors of normative perceptions and alcohol use across the transition to college. Journal of College Student Development. 2010;51(5):496. doi: 10.1353/csd.2010.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Roldan A, Parra I, Villanueva-Blasco VJ. Attitudes toward Cannabis of users and non-users in Spain: a Concept Mapping Study among University students. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11469-022-00835-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amado BG, Villanueva VJ, Vidal-Infer A, Isorna M. Diferencias de género entre autocultivadores de cannabis en España. Adicciones. 2020;32(3):181–192. doi: 10.20882/adicciones.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-de la Torre J, Fernández-Villa T, Molina A, Amezcua C, Mateos R, Cancela JM, Delgado M, Ortiz R, Alguacil J, Almaraz A, Gómez I, Blazquez G, Martín V. Drug use, family support and related factors in university students. A cross-sectional study based on the uniHcos Project data. Gaceta sanitaria. 2019;33:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balluerka, N., Gómez, J., Hidalgo, D., Gorostiaga, A., Espada, P., Padilla, J., & Santed, G. (2020). Las consecuencias psicológicas de la COVID-19 y el confinamiento. Informe de investigación. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad del País Vasco. Retrieved on 18 April, 2021 from https://addi.ehu.es/bitstream/handle/10810/45924/Consecuencias%20psicol%C3%B3gicas%20COVID-19%20PR3%20DIG.pdf?sequence=1

- Buckner JD, Walukevich KA, Lemke AW, Jeffries ER. The impact of university sanctions on cannabis use: individual difference factors that predict change in cannabis use. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 2018;4(1):76–84. doi: 10.1037/tps0000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca-Royo AM, Sanchez-Niubo A, Forero CG, Torrens M, Suelves JM, Domingo-Salvany A. Psychometric properties of the CAST and SDS scales in young adult cannabis users. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:709–715. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CN, Slutske WS, Martin NG, Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Identifying subtypes of cannabis users based on simultaneous polysubstance use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;205:107696. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J, Dutton M, Perry J. How do online students differ from lecture students. Journal of asynchronous learning networks. 2002;6(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction [EMCDDA] (2020). ESPAD report 2019: results from the European school survey project on alcohol and other drugs. Publications Office. Retrieved on 20 December, 2020 from https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2810/970957

- Fischer B, Russell C, Sabioni P, van den Brink W, Le Foll B, Hall W, Rehm J. Lower-risk cannabis use guidelines: a comprehensive update of evidence and recommendations. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;107:1277–1277. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Peñalvo FJ, Almuzara C, Abella A, García V, de Grande M. La evaluación online en la educación superior en tiempos de la COVID-19. Education in the Knowledge Society: EKS. 2020;12:1–26. doi: 10.14201/eks.23013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glodosky NC, Cuttler C. Motives Matter: Cannabis use motives moderate the associations between stress and negative affect. Addictive Behaviors. 2020;102:106188. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor modified drinking motives Questionnaire-Revised in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves L, Hemsing N. Sex and gender interactions on the use and impact of recreational cannabis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(2):509. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grevenstein D, Nagy E, Kroeninger-Jungaberle H. Development of risk perception and substance use of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis among adolescents and emerging adults: evidence of directional influences. Substance Use & Misuse. 2015;50(3):376–386. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.984847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groshkova T, Stoian T, Cunningham A, Griffiths P, Singleton N, Sedefov R. Will the current COVID-19 pandemic impact on long-term cannabis buying practices? Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart-Hargrove, L. C. y, & Dow-Edwards, D. L. (2012). Withdrawal from THC during adolescence: sex differences in locomotor activity and anxiety. Behavioural Brain Research, 231, 48–59. 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Avila CA, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR. Opioid-, cannabis-and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Serrano O, Gras ME, Font-Mayolas S. Concurrent and simultaneous use of cannabis and tobacco and its relationship with academic achievement amongst university students. Behavioral Sciences. 2018;8(3):31. doi: 10.3390/bs8030031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuero, D. (2018). ¿Qué va a ser de ti lejos de casa? (Consumo de sustancias tóxicas en universitarios españoles y su relación con el lugar de residencia. Proyecto uniHcos). Universidad de Valladolid. Retrieved on 12 April, 2021 from https://uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/handle/10324/36519/TFG-M-M1498.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Hser YI, Mooney LJ, Huang D, Zhu Y, Tomko RL, McClure E, Chou C, Gray KM, Author C. Reductions in Cannabis Use are Associated with improvements in anxiety, depression, and sleep quality, but not quality of life. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2017;81:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto nacional de estadística [INE] (2019). Encuesta sobre Equipamiento y Uso de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en los Hogares. Retrieved on 20 March, 2020 from https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2019.pdf

- Isorna M, Amado BG, Cajal B, Seijo D. Perfilando los consumidores de cannabis que autocultivan a pequeña escala. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology. 2016;32(3):871–878. doi: 10.6018/analesps.32.3.218561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar N, Chaiton M, Goodwin R, Schwartz R, O’Connor S, Kaufman P. Co-use and mixing tobacco with cannabis among Ontario adults. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2021;23(1):171–178. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempova, D., Sánchez, A., Vicente, J., Barrio, G., Domingo, A., Suelves, J. M., & Ramirez, V. (2009). Consumo problemático de cannabis en estudiantes españoles de 14–18 años: Validación de escalas. Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social.

- Legleye S, Karila L, Beck F, Reynaud M. Validation of the CAST, a general population Cannabis abuse screening test. Journal of Substance Use. 2007;12(4):233–242. doi: 10.1080/14659890701476532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ley de protección de datos personales y garantía de derechos digitales, del 5 de diciembre [Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 on personal data protection and digital rights guarantee]. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 294, del 6 de diciembre de 2018. Retrieved on 16 March, 2020 from https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2018/12/05/3

- Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones [OEDA] (2020). EDADES Informe 2019. Alcohol, tabaco y otras drogas ilegales en España. Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas. Retrieved on 24 January, 2021 from http://www.pnsd.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/sistemasInformacion/sistemaInformacion/pdf/2019_Informe_EDADES.pdf

- Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones [OEDA] (2021). Estadísticas 2021. Alcohol, tabaco y drogas ilegales en España. Ministerio de Sanidad. Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas; 2021. 213 p.

- Páramo MF, Cadaveira F, Tinajero C, Rodríguez MS. Binge drinking, cannabis co-consumption and academic achievement in first year university students in Spain: academic adjustment as a mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(2):542. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirona, A., Noor, A., & Burkhart, G. (2015, septiembre). Tobacco in cannabis joints: Why are we ignoring it? Póster presentado en Lisbon Addictions Conference 2015, Lisboa, Portugal.

- Rodríguez, M. A. F., Moreno, S. D., & Gómez, Y. F. (2019). La influencia de los roles de género en el consumo de alcohol: estudio cualitativo en adolescentes y jóvenes en Asturias. Adicciones,31(4), 260–273. 10.20882/adicciones.1003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rogers AH, Shepherd JM, Garey L, Zvolensky MJ. Psychological factors associated with substance use initiation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293:113407. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Kurosawa M, Benedek DM. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2020;74(4):281. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirado R, Aguaded JI, Marín I. Patrones de consumo de drogas y ocupación del ocio en estudiantes universitarios. Sus efectos sobre el hábito de estudio. Revista Española de Drogodependencias. 2010;35(4):467–479. [Google Scholar]

- Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Rodriguez A, Dunbar MS, Pedersen ER, Davis JP, Shih RA, D’Amico EJ. Cannabis and tobacco use and co-use: trajectories and correlates from early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;204:107499. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, V. J., Herrera-Gutiérrez, E., Redondo-Martín, S., Isorna, M., & Lozano-Polo, A. (2021). Proyecto piloto de promoción de la salud en consumo dual de cannabis y tabaco en universitarios: ÉVICT-Universidad. Global Health Promotion, 162–171. 10.1177/17579759211007454

- Walsh H, McNeill A, Purssell E, Duaso M. A systematic review and bayesian meta-analysis of interventions which target or assess co-use of tobacco and cannabis in single-or multi-substance interventions. Addiction. 2020;115(10):1800–1814. doi: 10.1111/add.14993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers CE, Shokri-Kojori E, Wong CT, Abi-Dargham A, Demiral ŞB, Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Volkow ND. Cannabis Abusers Show Hypofrontality and blunted brain responses to a stimulant challenge in females but not in males. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(10):2596–2605. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm J, Abudayyeh H, Perreras L, Taylor R, Peters EN, Vandrey R, Hedeker D, Mermelstein R, Cohn A. Measuring the temporal association between cannabis and tobacco use among co-using young adults using ecological momentary assessment. Addictive Behaviors. 2020;104:106250. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenebe, Y., y, & Necho, M. (2019). Socio-demographic and substance-related factors associated with mental distress among Wollo university students: institution-based cross-sectional study. Annals of General Psychiatry, 18, 28. 10.1186/s12991-019-0252-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]