Abstract

Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, and Bordetella bronchiseptica are closely related subspecies that cause respiratory tract infections in humans and other mammals and express many similar virulence factors. Their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) molecules differ, containing either a complex trisaccharide (B. pertussis), a trisaccharide plus an O-antigen-like repeat (B. bronchiseptica), or an altered trisaccharide plus an O-antigen-like repeat (B. parapertussis). Deletion of the wlb locus results in the loss of membrane-distal polysaccharide domains in the three subspecies of bordetellae, leaving LPS molecules consisting of lipid A and core oligosaccharide. We have used wlb deletion (Δwlb) mutants to investigate the roles of distal LPS structures in respiratory tract infection by bordetellae. Each mutant was defective compared to its parent strain in colonization of the respiratory tracts of BALB/c mice, but the location in the respiratory tract and the time point at which defects were observed differed significantly. Although the Δwlb mutants were much more sensitive to complement-mediated killing in vitro, they displayed similar defects in respiratory tract colonization in C5−/− mice compared with wild-type (wt) mice, indicating that increased sensitivity to complement-mediated lysis is not sufficient to explain the in vivo defects. B. pertussis and B. parapertussis Δwlb mutants were also defective compared to wt strains in colonization of SCID-beige mice, indicating that the defects were not limited to interactions with adaptive immunity. Interestingly, the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb strain was defective, compared to the wt strain, in colonization of the respiratory tracts of BALB/c mice beginning 1 week postinoculation but did not differ from the wt strain in its ability to colonize the respiratory tracts of B-cell- and T-cell-deficient mice, suggesting that wlb-dependent LPS modifications in B. bronchiseptica modulate interactions with adaptive immunity. These data show that biosynthesis of a full-length LPS molecule by these three bordetellae is essential for the expression of full virulence for mice. In addition, the data indicate that the different distal structures modifying the LPS molecules on these three closely related subspecies serve different purposes in respiratory tract infection, highlighting the diversity of functions attributable to LPS of gram-negative bacteria.

Bordetellae are gram-negative bacteria that cause respiratory tract infections in mammals. Bordetella pertussis infects only humans, causing whooping cough (pertussis) in unvaccinated children and a milder coughing illness in adults. B. parapertussis also infects humans and causes a similar, albeit less severe, disease. B. bronchiseptica infects a variety of four-legged mammals, causing atrophic rhinitis in pigs, kennel cough in dogs, and snuffles in rabbits. Most B. bronchiseptica infections, however, are asymptomatic (8). Very small numbers of B. bronchiseptica organisms are sufficient to establish persistent infection in laboratory animals including rabbits, rats, and mice, allowing this subspecies to be used as a model for studies of naturally occurring host-pathogen interactions (1, 9, 14, 15). These three Bordetella subspecies are very closely related and express a similar set of virulence factors under the regulatory control of the BvgAS two-component system (24, 25). Virulence factors conserved between them, such as the putative adhesins filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin, and fimbriae and the adenylate cyclase toxin, are likely to perform functions required by all three subspecies for successful respiratory tract colonization (8).

Thus far, major phenotypic differences between bordetellae have not been shown to result from the presence or absence of pathogenicity islands, bacteriophage genomes, transposable elements, or plasmids. Instead, several Bvg-regulated loci found in the genomes of these three subspecies are differentially expressed. Examples include the genes and operons that encode a motility apparatus (2, 3), the pertussis toxin (7), and possibly a type III secretion system (28, 29). These differentially expressed factors are likely to contribute to subspecies-specific characteristics such as host specificity and the ability to cause pathology and to persist.

The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) molecules expressed on the surface of B. pertussis, B. parapertussis, and B. bronchiseptica also differ substantially (4, 5, 17, 23). The observation that LPS structures are regulated by the BvgAS virulence control system suggests that these molecules play a role in respiratory tract infection (16, 17). B. pertussis LPS resolves as two bands when separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE); these bands are designated bands A and B. Band B (Fig. 1) is composed of lipid A and a branched-chain core oligosaccharide. Addition of a trisaccharide to the band B form creates a larger LPS molecule (actually a lipooligosaccharide), referred to as band A (composed of band B plus trisaccharide). B. bronchiseptica expresses LPS molecules that are very similar antigenically and electrophoretically to B. pertussis bands A and B, as well as a form containing an O-antigen-like homopolymer of 2,3-dideoxy-2,3-di-N-acetylgalactosaminuronic acid (2,3-di-NAcGalA), primarily in the Bvg− phase (12). B. parapertussis expresses a faster-migrating minimal molecule (band B′), as well as a large molecule containing the same O-antigen-like structure as B. bronchiseptica, and does not express the trisaccharide.

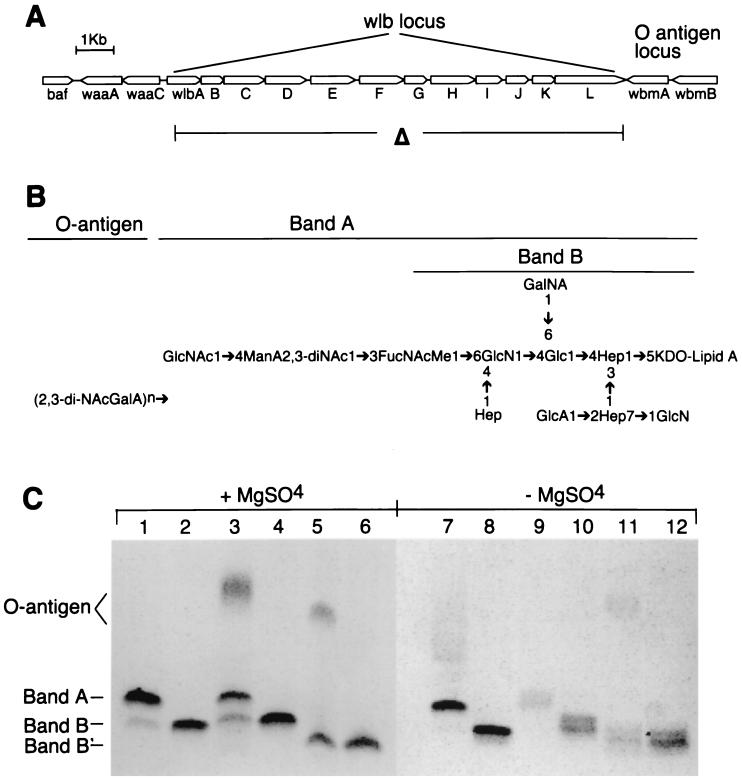

FIG. 1.

(A) Diagram depicting the genetic organization of the wlb locus. The locus consists of 12 genes, wlbA to wlbL, that are required for expression of band A LPS (B). The locus is flanked on one side by Bvg accessory factor (baf) and waaA and waaC, which encode the LPS biosynthesis functions 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid transferase and heptosyltransferase, respectively. In B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis, the other side is flanked by the LPS O-antigen biosynthetic locus (23). In B. pertussis, this locus has been replaced by an insertion sequence. In the Δwlb mutants, the wlb locus has been deleted (as indicated in the diagram) and replaced by an antibiotic resistance cassette. (B) Schematic diagram of Bordetella LPS, as elucidated for B. pertussis strain 1414 (17). Band B, as viewed by SDS-PAGE (C), is composed of lipid A and a core containing several charged sugars including galactosaminuronic acid, glucuronic acid, and glucosamine. The wlb locus is required for the band B structure to be further substituted by a trisaccharide comprising N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), 2,3-dideoxy-2,3-di-N-acetylmannosaminuronic acid (2,3-diNAcManA), and N-acetyl-N-methylfucosamine (FucNAcMe) to form band A, the predominant LPS form expressed by B. pertussis. B. parapertussis expresses a smaller core, as suggested by the faster-migrating band B, and contains a mutated wlbH, which decreases the efficiency of GlcNAc transfer to the LPS, resulting in a truncated band A (14, 19). On wt B. parapertussis, virtually all band A LPS is further substituted by O antigen and thus a distinct band A is not seen. Both B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis synthesize a polymeric O antigen reported to consist of 2,3-dideoxy-2,3-di-N-acetylgalactosaminuronic acid (18). The attachment site for the O antigen is in the core but has not been precisely determined. 2,3-di-NAcGalA, 2,3-dideoxy-2,3-di-N-acetylgalactosaminuronic acid; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; ManA2,3-diNAc, 2,3-dideoxy-2,3-di-N-acetylmannosaminuronic acid; FucNAcMe, N-acetyl-N-methylfucosamine; GlcN, glucosamine; GalNA, galactosaminuronic acid; Glc, glucose; Hep, l-glycero-d-mannoheptose; GlcA, glucuronic acid; KDO, 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid. (C) SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining of LPS prepared from wt B. pertussis (lanes 1 and 7), B. pertussis Δwlb (lanes 2 and 8), wt B. bronchiseptica (lanes 3 and 9), B. bronchiseptica Δwlb (lanes 4 and 10), wt B. parapertussis (lanes 5 and 11), and B. parapertussis Δwlb (lanes 6 and 12). Bacteria were grown in the presence or absence of MgSO4, as indicated, to produce Bvg− or Bvg+ bacteria, respectively.

The wlb gene cluster, composed of 12 genes, is required for biosynthesis and addition of the trisaccharide in band A of B. pertussis and B. bronchiseptica and the O-antigen-like repeat in B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis (4, 6). Strains containing a wlb deletion mutation (Δwlb) express only the smallest form of LPS that naturally occurs on these cells, band B on B. pertussis and B. bronchiseptica and band B′ on B. parapertussis. The presence of these structurally diverse LPS molecules in otherwise closely related bacteria provides an opportunity to investigate the roles of these structures in infection. Here we have compared the wild-type (wt) and Δwlb strains of each subspecies in mouse respiratory tract infection models. All three mutants were defective in colonization of the respiratory tracts of BALB/c mice, but each was defective in different respiratory organs and/or at different periods during infection. Immunocompromised mice were used to investigate potential interactions between LPS structures and specific aspects of host immunity. Together, these results suggest that the distal structures of the LPS molecules of these three subspecies play different roles in infection. In B. pertussis they are required for efficient nasal colonization. In B. parapertussis they are required for initial colonization of the lungs. In B. bronchiseptica they are required for extended survival in the lower respiratory tracts of normal mice but not mice lacking adaptive immunity, suggesting that these structures are involved in resisting adaptive immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Bacteria were maintained on Bordet-Gengou (BG) agar (Difco), inoculated into Stainer-Scholte broth at optical densities of 0.1 or lower, and grown to mid-log phase at 37°C on a roller drum for assays and inoculations. For Bvg− phase cultures, MgSO4 was added to a final concentration of 40 mM. Wild-type (wt) strains (BP536, RB50, and CN2591) and the Δwlb derivatives of these three Bordetella subspecies have been described previously (4).

LPS preparation and SDS-PAGE.

LPS was purified, using a modification of the method of Hitchcock and Brown (6, 16), from bacteria grown on BG agar plates with 15% defibrinated blood and supplemented with 200 μg of streptomycin per ml. LPS was analyzed using the PAGE-Tricine buffer system by method of Lesse et al. (18). Silver staining was performed by the method of Tsai and Frasch (22).

Animal experiments.

Female BALB/c mice, 4 to 6 weeks old, were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. SCID-beige mice were obtained from University of California Los Angeles facilities. C5−/− mice (B10.D2-H2dH2-T18cHc0/nSnJ) and congenic controls (B10.D2-H2dH2-T18cHc1/nSnJ) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Mice lightly sedated with halothane were inoculated with the indicated dose of bacteria by pipetting either 5 or 50 μl of the inoculum onto the tip of the external nares. For time course experiments, groups of four animals were sacrificed on day 0, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 28, or 50 postinoculation. Colonization of various organs was quantified by homogenizing each tissue in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), plating aliquots onto BG-blood agar, and counting colonies after 2 (B. bronchiseptica), 3 (B. parapertussis) or 4 (B. pertussis) days of incubation at 37°C. For the production of survival curves, after the progression of disease became clear, moribund animals were euthanized to prevent unnecessary suffering. Animals were handled in accordance with institutional guidelines. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t test.

Serum-killing assays.

Bordetella-free rabbits were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, and their serum was confirmed to be free of Bordetella-specific antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and a Western immunoblot assay (data not shown). Immune serum was obtained from rabbits inoculated with B. bronchiseptica and colonized for 6 months (14). The serum was maintained complement active and was frozen in single-use aliquots at −80°C. Bacteria were grown in Stainer-Scholte broth to mid-log phase and diluted in PBS to 100 CFU/μl. Serum was thawed on ice, and 90 μl of serum, heat-killed serum, or PBS was mixed with 10 μl of PBS containing 1,000 CFU of bacteria. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Samples were spread on BG agar plates and incubated for 2 to 4 days to determine bacterial numbers.

RESULTS

Deletion of the wlb locus results in truncated LPS structures.

To examine the effect of deleting the wlb locus on LPS biosynthesis under Bvg+ and Bvg− conditions, we compared, by silver-stained Tricine-SDS-PAGE, LPS structures of wt and Δwlb strains grown at 37°C on BG agar (Bvg+ conditions) or BG agar with 40 mM MgSO4 (Bvg− conditions). In agreement with previous reports, deletion of the wlb locus in B. pertussis resulted in the loss of the slower-migrating band A and the accumulation of the faster-migrating band B, representing the loss of the terminal trisaccharide (Fig. 1C, lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8) (6). wt B. bronchiseptica expressed molecules that comigrate with bands A and B, as well as slower-migrating molecules that contain O-antigen-like repeats (20), which are observed primarily in the Bvg− phase (lanes 3 and 9). Deletion of the wlb locus in B. bronchiseptica resulted in the loss of the slower-migrating forms of LPS and the accumulation of band B (lanes 4 and 10). B. parapertussis lacks band A but expresses a molecule that migrates somewhat faster than band B (band B′), as well as a larger form containing O-antigen-like repeats (lanes 5 and 11) (20). We have previously shown that deletion of genes required for O-antigen assembly in B. parapertussis results in accumulation of a species intermediate in size between bands A and B, probably representing the addition of a disaccharide by the wlb genes (20). This molecule is presumably efficiently substituted by O-antigen-like repeats in wt bacteria. Deletion of the entire wlb locus in B. parapertussis resulted in slight accumulation of the faster-migrating band B′ and loss of the high-molecular-weight O-antigen-containing species (lanes 6 and 12). Under Bvg+ growth conditions, additional bands appeared above bands B and B′ in B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis wt and Δwlb strains, indicating that BvgAS-dependent modifications of these molecules occur that are not dependent on the presence of the terminal trisaccharide or the O-antigen-like repeat. Together, these data show that in all three subspecies, deletion of the wlb locus resulted in the loss of larger forms of LPS and an apparent accumulation of the smaller forms, bands B and B′. Because it is possible that changing the LPS structure could affect other molecules that associate with or pass through the outer membrane, we extensively characterized the Δwlb mutants in vitro. Deletion of the wlb locus did not affect growth rate, colony morphology, hemolysis, or expression of antigenic surface or secreted proteins as assessed by immunoblotting using sera from infected animals and serum raised against specific factors including pertactin, FHA, and adenylate cyclase toxin (data not shown). The Δwlb mutation did not affect FHA-dependent binding to L2 cells in vitro, indicating that FHA is present and functional on the surface of these cells (10).

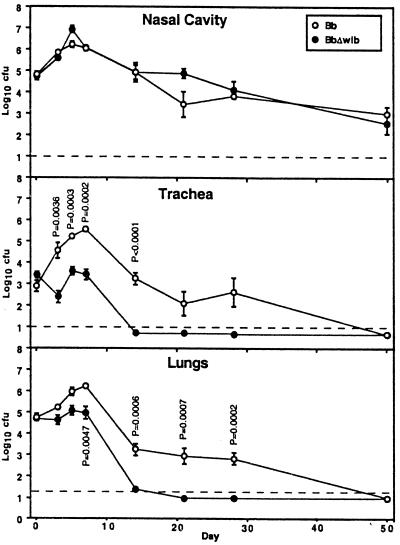

B. bronchiseptica requires wlb-dependent LPS modification for efficient colonization of the trachea and lungs of BALB/c mice.

To determine the role of the trisaccharide and O-antigen-like structures of LPS in B. bronchiseptica respiratory tract colonization, BALB/c mice were inoculated intranasally with 5 × 105 CFU of wt or Δwlb B. bronchiseptica in 50 μl of PBS (Fig. 2). This inoculation regimen consistently delivers approximately 105 CFU to the nasal cavity, 105 CFU to the lungs, and 103 CFU to the trachea (Fig. 2 to 4, day 0). On subsequent days, B. bronchiseptica was recovered from all three sites at numbers larger than the initial inoculum, indicating that it was able to colonize and multiply throughout the respiratory tract as we have previously shown (14). After 1 week the numbers of wt bacteria colonizing the respiratory tract decreased but bacteria were still recovered from both the trachea and the lungs 28 days after inoculation. In contrast, the Δwlb mutant did not increase in numbers in the trachea and lungs during the first week and could no longer be recovered from the lower respiratory tract by day 14 postinoculation. At multiple consecutive time points beginning on day 3, the numbers of Δwlb bacteria were significantly smaller (P < 0.01) than those of the wt strain in both the trachea and the lungs. Although defective in tracheal and lung infection, the Δwlb strain was indistinguishable from the wt strain in colonization of the nasal cavity.

FIG. 2.

The B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant is defective in tracheal and lung colonization in BALB/c mice. Groups of 4-week-old female mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU of either wt B. bronchiseptica or its Δwlb derivative delivered in a 50-μl volume of PBS into the nares. Data points are presented as mean log10 CFU and standard error. P values are shown where P < 0.02.

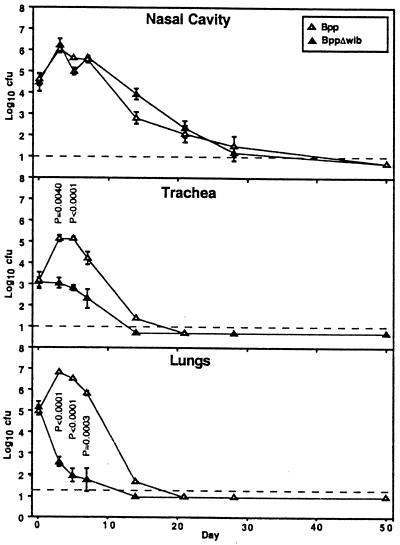

FIG. 4.

The B. pertussis Δwlb mutant is defective in nasal, tracheal, and lung colonization in BALB/c mice. Groups of 4-week-old female mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU of either wt B. pertussis or its Δwlb derivative delivered in a 50-μl volume of PBS into the nares. Data points are presented as mean log10 CFU and standard error. P values are shown where P < 0.02.

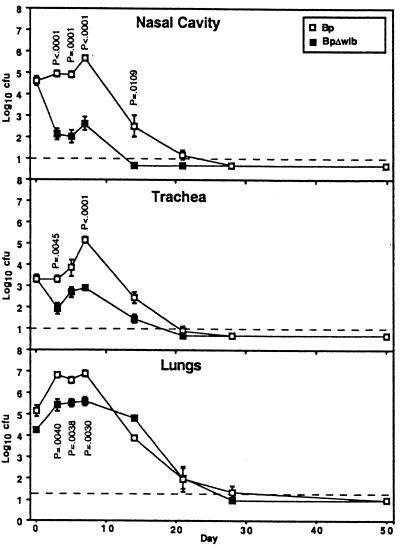

B. parapertussis requires wlb-dependent LPS modification for efficient colonization of the trachea and lungs of BALB/c mice.

Clinical isolates of B. parapertussis from humans are essentially clonal and appear to have diverged from B. bronchiseptica relatively recently (27). wt B. parapertussis behaved similarly in most respects to wt B. bronchiseptica in BALB/c mice inoculated intranasally as above (compare Fig. 2 and 3). By day 3 postinoculation, wt B. parapertussis was recovered from the nasal cavity, trachea, and lungs at numbers larger than the initial inoculum, indicating that it was able to colonize and multiply throughout the respiratory tract. After about 5 days, the numbers of wt bacteria began to decrease in all three organs and were below detectable levels in the trachea and lungs by day 21 and in the nasal cavity by day 50 postinoculation. The B. parapertussis Δwlb strain was similar to the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb strain in that it was recovered at relatively constant numbers in the trachea for the first week and was absent by the second week. However, the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant differed from the B. bronchiseptica mutant in the magnitude of its defect in the lungs observed by day 3 postinoculation. On postinoculation days 3, 5, and 7, the numbers of B. parapertussis Δwlb bacteria were 1/100 those of the wt strain in the trachea and 1/10,000 those of the wt strain in the lungs. The B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant was similar to the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant in that it was indistinguishable from the wt strain in colonization of the nasal cavity.

FIG. 3.

The B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant is defective in tracheal and lung colonization in BALB/c mice. Groups of 4-week-old female mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU of either wt B. parapertussis or its Δwlb derivative delivered in a 50-μl volume of PBS into the nares. Data points are presented as mean log10 CFU and standard error. P values are shown where P < 0.02.

B. pertussis requires wlb-dependent LPS modification for efficient colonization of the nose, trachea, and lungs of BALB/c mice.

In the mouse model, B. pertussis efficiently colonizes the lungs but is defective, compared to B. bronchiseptica, in persistence in the nasal cavity (14). Although the wt B. pertussis strain was recovered from the nasal cavity, trachea, and lungs at numbers larger than the initial inoculum (Fig. 4, compare days 0 and 3), after a week the numbers of wt bacteria decreased and were below detectable levels in the trachea and nose by day 28 postinoculation. On day 28 postinoculation a small number of wt bacteria were recovered from the lungs, but by day 50 none were detected in any of the sites surveyed. The B. pertussis Δwlb mutant was similar to the B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis Δwlb mutants in that it was recovered at relatively constant numbers in the trachea for the first week. In contrast to the B. parapertussis mutant, the B. pertussis Δwlb mutant multiplied roughly 10-fold in numbers in the lungs during the first few days postinoculation and stayed at that approximate level for 2 weeks before declining and disappearing by day 28. Although neither the B. bronchiseptica nor the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutants were defective in the nasal cavity of BALB/c mice, the B. pertussis Δwlb mutant was defective, with bacterial numbers approximately 1/1,000 those of the wt strain on days 3, 5, and 7 and below detectable levels by day 14 postinoculation. The numbers of B. pertussis Δwlb mutant bacteria were decreased, compared to the wt strain, in all three organs (P < 0.01 at multiple time points) but were most severely defective in colonization of the nasal cavity, a phenotype not observed with Δwlb mutants of the other two subspecies.

wlb-dependent LPS modification is required for lethal infection of SCID-beige mice by B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis.

The decrease in colonization levels throughout the respiratory tracts of BALB/c mice after day 7 postinoculation suggests that adaptive immunity is effective, albeit to different extents, against all three subspecies. We have previously used mice deficient in B and T cells (SCID, SCID-beige, and RAG-1 knockout mice) to identify interactions between bacterial virulence factors and innate versus adaptive immune responses (14, 15, 28). B. bronchiseptica is highly virulent in SCID, SCID-beige, and RAG-1 knockout mice, causing lethal systemic infections. B. pertussis is less virulent and does not kill these animals but persists for at least 200 days in the nose, trachea, and lungs (14). To identify potential roles for wlb-dependent LPS modifications in persistence and virulence, we compared the ability of these three Bordetella subspecies and their Δwlb mutants to infect SCID-beige mice (BALB/c genetic background), which are deficient in B and T cells as well as NK-cell activities. The beige mutation alone does not affect B. bronchiseptica infection, but in the context of SCID mice it speeds the progression of disease (15).

A low-dose, low-volume inoculum of 500 CFU in 5 μl of PBS was delivered to the external nares, and survival was monitored over time. All six groups of mice remained healthy for 30 days, after which the animals infected with wt B. bronchiseptica began to display signs of illness such as piloerection, weight loss, hunched stature, listlessness, and, eventually, loss of responsiveness followed by death of 100% of the animals between days 40 and 70 postinoculation (Fig. 5A) (15). Mice inoculated with the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant, in contrast, remained healthy for more than 200 days, indicating that wlb-dependent LPS modification is required for B. bronchiseptica to cause lethal infection in SCID-beige mice. Animals infected with either wt B. pertussis, B. parapertussis, or their Δwlb mutants remained healthy for more than 200 days.

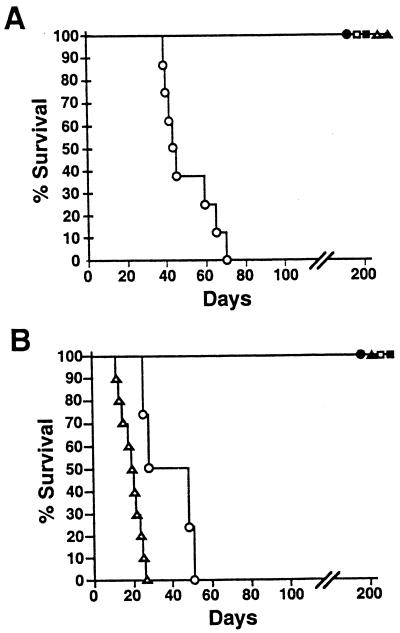

FIG. 5.

Survival of SCID-beige mice following inoculation with Bordetella subspecies and their Δwlb mutants. SCID-beige mice were inoculated with either wt (open symbols) or Δwlb mutant (solid symbols) B. bronchiseptica (circles), B. parapertussis (triangles), or B. pertussis (squares). Percent survival is presented as a function of time following low-dose, low-volume intranasal inoculation with 500 CFU in a 5-μl PBS droplet (A) or high-dose, high-volume intranasal inoculation with 5 × 105 CFU in 50 μl of PBS (B).

SCID-beige mice were also inoculated with a high-dose high-volume regimen (5 × 105 CFU in 50 μl of PBS), which seeds the entire respiratory tract with bacteria and deposits approximately 105 CFU in the lungs (Fig. 5B). B. bronchiseptica delivered by this regimen killed SCID-beige mice with slightly faster kinetics than the low-dose regimen did. wt B. parapertussis, which did not kill SCID-beige mice following low-dose inoculation, killed SCID-beige mice within 30 days following high-dose inoculation. B. pertussis and all three Δwlb mutants, however, did not cause lethal infections in these immunocompromised mice, even using the high-dose, high-volume regimen. These results highlight major differences in the virulence of B. pertussis, B. parapertussis, and B. bronchiseptica in this model and show that wlb-dependent LPS modification is required for the virulence of both B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis in SCID-beige mice.

Colonization levels in SCID-beige mice.

The three Δwlb mutants differed in the time points and anatomical locations at which they were defective in immunocompetent mice. To determine which, if any, of these colonization defects may relate to an ability to resist adaptive immune responses, we inoculated SCID-beige mice by the high-dose, high-volume regimen and determined colonization levels in various organs 25 days postinoculation. wt B. bronchiseptica was recovered at large numbers throughout the respiratory tract and at systemic sites including the livers of SCID-beige mice (Fig. 6) (14, 15). The B. bronchiseptica Δwlb strain was recovered at similar numbers to the wt strain throughout the respiratory tract but was not recovered from systemic sites such as the liver. Even at 100 and 200 days postinoculation, the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb strain maintained a high level of colonization in the respiratory tract but was not recovered from the liver or spleen (data not shown). These data indicate that in SCID-beige mice, wlb-dependent LPS modification is not required for B. bronchiseptica colonization of the respiratory tract, suggesting that the defect of the Δwlb mutant in the lungs and trachea of BALB/c mice after 1 week is a result of B-cell, T-cell, and/or NK-cell function. The B. bronchiseptica wlb locus is, however, absolutely required for systemic spread to the liver and for lethal infection in SCID-beige mice.

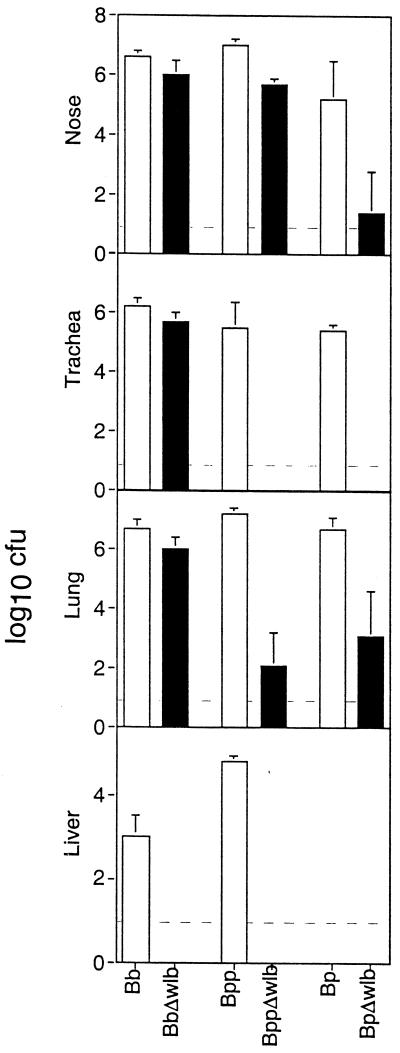

FIG. 6.

Colonization of various tissues of SCID-beige mice by wt and Δwlb strains. Groups of four female 4-week-old SCID-beige mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU in 50 μl of PBS. The mice were sacrificed and the colonization levels in various organs were determined on day 25 postinoculation for B. pertussis strains (Bp) and B. bronchiseptica strains (Bb) and day 21 for B. parapertussis strains (Bpp). Data are presented as mean log10 CFU and standard error. The dashed line represents the lower limit of detection.

SCID-beige mice inoculated with wt B. parapertussis contained large numbers of bacteria throughout the respiratory tract as well as the liver at 25 days postinoculation (Fig. 6). In BALB/c mice inoculated with the same dose of wt B. parapertussis, the trachea and lungs were cleared and the nasal cavity was nearly cleared by day 21 postinoculation (Fig. 3). These data indicate that immune mechanisms present in BALB/c mice but absent from SCID-beige mice are required to clear B. parapertussis infection. The Δwlb mutant was only slightly defective, compared to wt B. parapertussis, in colonization of the nasal cavities of SCID-beige mice but was severely defective in colonization of the tracheas and lungs of these animals. The striking defects of the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant in the tracheas and lungs of SCID-beige mice and the similar defect observed within 3 days postinoculation in BALB/c mice indicate that B. parapertussis wlb-dependent LPS modification is required for colonization of these sites even in the absence of adaptive immunity. These data suggest that in B. parapertussis the wlb-dependent LPS modifications are involved in some aspect of infection other than interactions with adaptive immunity.

wt B. pertussis was recovered at large numbers throughout the respiratory tracts of SCID-beige mice 25 days postinoculation but not elsewhere in these animals (Fig. 6). We have previously shown that wt B. pertussis remains at relatively constant levels throughout the respiratory tracts of SCID-beige mice for at least 200 days but causes no overt signs of disease (14). The B. pertussis Δwlb mutant was defective, compared to the wt strain, in the noses, tracheas, and lungs of both BALB/c and SCID-beige mice, indicating that wlb-dependent LPS structures are required for some function other than evading the host adaptive immune responses.

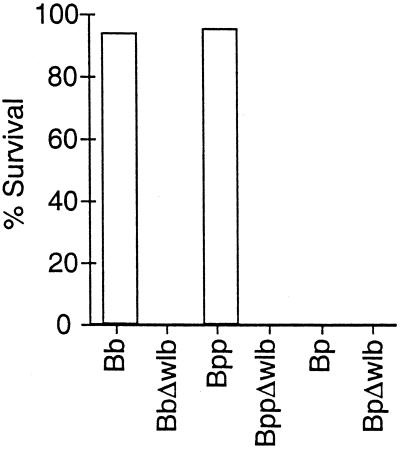

wlb-dependent LPS modification is required by B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis for resistance to killing by naive serum.

wt B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis, but not their Δwlb mutants, were able to infect the livers of SCID-beige mice, suggesting that they could survive the antimicrobial activities of blood and lymph fluids encountered during transit to the liver. We reasoned that these Δwlb mutants could be defective in causing lethal systemic disease due to an increased susceptibility to antimicrobial factors in serum. We therefore compared wt and Δwlb strains of the three Bordetella subspecies for their survival in complement-active serum from B. bronchiseptica-free rabbits (naive serum). Bacteria (1,000 CFU) from mid-log-phase liquid cultures, grown under Bvg+ phase conditions, were incubated in 100 μl of 90% serum to ensure that serum components were not limiting. wt B. bronchiseptica was not killed by a 1-h incubation at 37°C in 90% naive serum (Fig. 7). In contrast, the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant was highly sensitive to naive serum (>99% of bacteria were killed), indicating that wlb-dependent LPS modification is required for B. bronchiseptica serum resistance. B. parapertussis was similar to B. bronchiseptica in that the wt strain was resistant but the Δwlb strain was killed (>99%) by naive serum. Unlike the other two subspecies, both wt and Δwlb B. pertussis strains were killed by naive serum in this assay.

FIG. 7.

Serum resistance of wt and Δwlb strains. Bacteria were grown to mid-log phase in Stainer-Scholte broth and diluted in PBS. A total of 1,000 bacteria were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in 100 μl of 90% naive serum. Serum resistance is presented as the percent survival relative to a PBS control. Naive and immune sera are described in Materials and Methods.

Sera from B. bronchiseptica-infected rabbits (immune serum) were shown to contain antibodies recognizing all three Bordetella subspecies by ELISA and Western analysis (reference 14 and data not shown). wt B. pertussis and all three subspecies of Δwlb mutants, which were killed by naive serum, were killed by immune serum, as expected (data not shown). Immune serum also killed wt B. bronchiseptica (>98% killing) and B. parapertussis (>95% killing), which were not killed by naive serum, suggesting that antibody-mediated complement activation is responsible for the killing. Similar results were obtained in multiple experiments with naive sera from mice, rats, and rabbits or immune sera from mice, rats, rabbits, and humans. Inhibition of complement with EDTA or by heat treatment prevented killing in these assays (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that wlb-dependent LPS modification is required for resistance of B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis to the alternative complement cascade (naive serum) but is not sufficient for resistance to the classical pathway of complement (immune serum).

Complement-deficient mice.

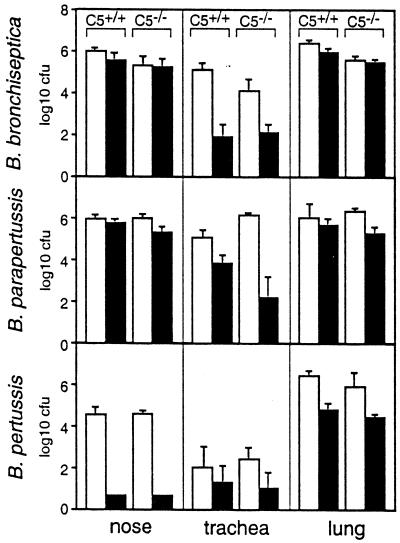

The sensitivity of the B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis Δwlb mutants to naive serum may be related to their defects in the BALB/c infection model. Serum components are present at low concentrations in normal respiratory fluids but increase in concentration in response to bacterial infection (13), suggesting that complement could affect colonization in the mouse model. SCID-beige mice contain normal complement levels, and the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant was also defective in colonization of these animals, but the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant colonized the respiratory tracts of SCID-beige animals to levels similar to those of the wt strain (Fig. 6). These data suggest that the colonization defect of the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb strain does not involve increased sensitivity to complement but that the defect of the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant may do so. To directly determine if complement-mediated lysis contributes to control of respiratory tract infection by bordetellae, we compared the wt and Δwlb strains in congenic mouse strains with and without the ability to express the C5 component of complement (11, 19), which is required for the assembly of the membrane attack complex involved in complement-mediated lysis of gram-negative bacteria. In C5−/− mice, complement activation by classical, alternative, or lectin pathways does not proceed past the point where these three pathways converge at the level of C5 activation prior to membrane attack complex formation, so that complement-mediated lysis is abrogated. In vitro, serum from C5+/+ mice killed B. pertussis and the Δwlb but not wt B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis strains but serum from congenic C5−/− mice did not (data not shown). In vivo, the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant was defective in colonization of the trachea, compared to the wt strain, in both C5+/+ and C5−/− mice on day 5 postinoculation (Fig. 8). Apparently the defect in tracheal colonization is not due to the increased sensitivity of the Δwlb mutant to complement-mediated killing. Likewise, both B. pertussis and B. parapertussis Δwlb mutants showed as great a defect in colonization of C5−/− mice as in C5+/+ mice, indicating that the defects are not due to increased sensitivity to complement-mediated killing. Interestingly, the B. parapertussis Δwlb strain, which was severely defective (1/10,000 of wt numbers) in the lungs of BALB/c mice on day 5 (Fig. 3) and SCID-beige mice (BALB/c genetic background) on day 21 (Fig. 6), showed little defect in the lungs of either C5+/+ or C5−/− mice (B10.D2 genetic background). These data suggest that the substantial defect of the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant in BALB/c lung colonization is not due to its sensitivity to complement-mediated killing but, rather, involves some other host factor that differs between mice of these two genetic backgrounds. The Δwlb mutants of all three subspecies, compared to their wt parent strains, were at least as defective in C5−/− mice as in C5+/+ mice, indicating that the role of the wlb locus is not merely to render the bacteria complement resistant. Some other function of the wlb-dependent LPS modification is therefore involved in the observed phenotypes. The Δwlb strains did not show increased sensitivity to defensins (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Bordetella Δwlb mutants are defective in colonization of the respiratory tracts of complement-deficient mice. Groups of four 6-week-old female C5+/+ and C5−/− mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 CFU in 50 μl of PBS. Colonization levels were determined in the nose, trachea, and lungs on day 5 postinoculation. Open bars represent wt strains, and solid bars represent Δwlb strains. Data are presented as mean log10 CFU and standard error. The lower limit of detection is approximately 1.

DISCUSSION

LPS structures expressed by gram-negative bacteria have been proposed to contribute to infection by a variety of mechanisms including the mediation of adherence to host cells, antigenic variation, molecular mimicry, and induction of blocking antibodies (21). The LPS structures of Bordetella subspecies are less well studied and have not been documented to perform any of these functions, although they are modified in a Bvg-dependent manner, suggesting that they are involved in infection (26). We have compared B. bronchiseptica, B. parapertussis, and B. pertussis wt and Δwlb strains in vitro and in vivo, in normal and immunodeficient mice, to investigate the roles of the distal domains of their LPS molecules in infection.

All three Δwlb strains were similarly defective, compared to their wt parent strains, in colonization of the tracheas of BALB/c mice; they failed to increase in numbers in the trachea over the first week postinoculation and declined in numbers rapidly in the second week. Although deletion of the wlb locus increased the sensitivity of B. bronchiseptica and B. parapertussis to complement-mediated killing in vitro, the Δwlb mutants were defective in colonization of the tracheas of C5−/− mice, in which complement-mediated killing is abrogated. These results indicate that complement-mediated lysis was not the only mechanism involved in the clearance of the Δwlb strains from the trachea, although it is possible that opsonization by C3, an event that does not require C5, could result in phagocytosis of the Δwlb strains. Interestingly, loss of distal LPS structures in the three Bordetella subspecies resulted in different phenotypes in the lungs and nasal cavities of various mice, supporting the view that these structures perform different functions for these three organisms.

Colonization of the lungs of BALB/c mice by the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant was not significantly reduced compared to the wt strain until about 7 days postinoculation. The mutant was cleared from the lungs by 14 days postinoculation, whereas the wt strain was not cleared until day 50. Therefore, wlb-dependent LPS modification is not required for initial infection of the lungs by B. bronchiseptica but appears to contribute to persistence at a time consistent with the development of adaptive immune responses. In mice lacking adaptive immunity, the Δwlb mutant colonized the respiratory tract to similar levels to those of the wt strain, supporting the view that wlb gene products are primarily involved in resisting clearance by adaptive immune functions. Together, these data suggest that wlb-dependent LPS structures are required for B. bronchiseptica to resist clearance by the adaptive immune response. In preliminary experiments in μMT(C57BL/6-Igh-6tm1Cgn) mice, lacking B cells, both wt and Δwlb strains persist in the trachea and lungs, consistent with the primary role of wlb-dependent LPS modification being modulation of antibody-mediated bacterial clearance (data not shown). The inability of the Δwlb mutant to cause systemic infections and kill mice lacking adaptive immunity (SCID-beige mice) may be due to its increased sensitivity to serum complement-mediated killing compared to wt B. bronchiseptica. Although B. bronchiseptica is not believed to invade cells or tissues during natural infection, these observation may be relevant to aspects of infection that are not yet understood.

The role of distal LPS structures in B. parapertussis and B. pertussis infections appears to be substantially different from that in B. bronchiseptica. The B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant was recovered from the lungs of BALB/c mice at 1/10,000 the numbers of the wt strain by day 3 postinoculation. A defect of similar magnitude was observed for this mutant in the lungs of SCID-beige mice. These data indicate that, in contrast to B. bronchiseptica, wlb-dependent LPS modification is required for B. parapertussis to colonize the lungs of mice even in the absence of adaptive immunity. Interestingly, the dramatic defect of the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant in the lungs of BALB/c and SCID-beige mice (BALB/c genetic background) was not observed in C5+/+ or C5−/− mice (B10.D2 genetic background). It is possible that wlb-dependent LPS modification protects bacteria from an antimicrobial activity present in BALB/c mice but absent in B10 mice. Alternatively, wlb-dependent LPS modification could be directly or indirectly required for binding to a receptor in BALB/c mice. B10 mice could express an alternative receptor(s), relieving the need for wlb-dependent LPS modification for lung infection in these animals.

Only B. pertussis required the wlb locus for efficient colonization of the nasal cavity. The B. pertussis Δwlb mutant was recovered from that organ at 1/1,000 the numbers of the wt strain. This defect was observed in the nasal cavities of BALB/c, SCID-beige, C5+/+, and C5−/− mice, indicating that the defect did not involve complement-mediated killing, adaptive immunity, or other interstrain differences between these animals. Interestingly, the B. pertussis Δwlb mutant was recovered from the tracheas and lungs of BALB/c mice at smaller numbers than the wt strain was on days 3, 5, and 7 postinoculation but thereafter the two strains were indistinguishable in these tissues. In contrast, the B. bronchiseptica Δwlb mutant was defective only on or after day 7 postinoculation and the B. parapertussis Δwlb mutant was severely defective at all time points from day 3 postinoculation onward.

The three Bordetella subspecies examined here are very closely related and are believed to have diverged from a common ancestor relatively recently (27). They maintain similar habitats, the respiratory tracts of mammals, and appear to differ primarily in their host ranges and in their ability to cause either acute disease with moderate to severe pathology or chronic infection with moderate to no pathology. Many of the factors involved in infection are highly conserved among the three subspecies, as would be expected for molecules that perform a function required for respiratory tract colonization in general. In contrast, the LPS structures of these three organisms appear to be substantially different. Although this could indicate that these structures have diverged because they are not important in infection, the data presented here show that they are critical to efficient respiratory tract colonization. The more likely explanation for these observations is therefore that these structures have evolved to meet the specific needs of these three organisms. For B. bronchiseptica, distal LPS structures are apparently required only when adaptive immunity has been generated, suggesting that they contribute to the persistent tracheal and lung infections characteristic of this subspecies. B. pertussis and B. parapertussis, which have independently shifted their host ranges to infect humans but do not cause persistent infections, appear to have modified their distal LPS structures to perform different roles. These functions are still required in SCID-beige mice, indicating that they are not limited to interactions with adaptive immunity. For B. pertussis, distal LPS structures are required for colonization of the nasal cavity of every mouse strain examined. For B. parapertussis, the Δwlb strain was severely defective (1/10,000 of wt levels) in colonization of the lungs of some mouse strains but not others. Together, these data suggest that the different distal structures modifying the LPS molecules on these three closely related subspecies serve different purposes in respiratory tract infection. Exchange of the genes involved in LPS assembly between the three subspecies will elucidate their roles in either common properties of respiratory tract colonization or subspecies-specific characteristics such as persistence, host specificity, and virulence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by USDA grant 960-1856 (to E.T.H.), USDA grant 1999-02298 (to J.F.M.), NIH grant AI38417 (to J.F.M.), NIH grant AI43986 (to P.A.C.), Wellcome Trust Project Grant 045666 (to D.J.M.), and Wellcome Trust Programme Grant 054588 (to D.J.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akerley B J, Cotter P A, Miller J F. Ectopic expression of the flagellar regulon alters development of the Bordetella-host interaction. Cell. 1995;80:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerley B J, Miller J F. Flagellin gene transcription in Bordetella bronchiseptica is regulated by the BvgAS virulence control system. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3468–3479. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3468-3479.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akerley B J, Monack D M, Falkow S, Miller J F. The bvgAS locus negatively controls motility and synthesis of flagella in Bordetella bronchiseptica. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:980–990. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.980-990.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen A, Maskell D. The identification, cloning and mutagenesis of a genetic locus required for lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:37–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.354877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen A G, Isobe T, Maskell D J. Identification and cloning of waaF (rfaF) from Bordetella pertussis and use to generate mutants of Bordetella spp. with deep rough lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:35–40. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.35-40.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen A G, Thomas R M, Cadisch J T, Maskell D J. Molecular and functional analysis of the lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis locus wlb from Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:27–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arico B, Rappuoli R. Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica contain transcriptionally silent pertussis toxin genes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2847–2853. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2847-2853.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter, P. A., and J. F. Miller. Bordetella. In E. Groisman (ed.), Principles of bacterial pathogenesis, in press. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 9.Cotter P A, Miller J F. BvgAS-mediated signal transduction: analysis of phase-locked regulatory mutants of Bordetella bronchiseptica in a rabbit model. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3381–3390. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3381-3390.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter P A, Yuk M H, Mattoo S, Akerley B J, Boschwitz J, Relman D A, Miller J F. Filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella bronchiseptica is required for efficient establishment of tracheal colonization. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5921–5929. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5921-5929.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Eustachio P, Kristensen T, Wetsel R A, Riblet R, Taylor B A, Tack B F. Chromosomal location of the genes encoding complement components C5 and factor H in the mouse. J Immunol. 1986;137:3990–3995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Fabio J L, Caroff M, Karibian D, Richards J C, Perry M B. Characterization of the common antigenic lipopolysaccharide O-chains produced by Bordetella bronchiseptica and Bordetella parapertussis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;76:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90348-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greiff L, Erjefalt I, Svensson C, Wollmer P, Alkner U, Andersson M, Persson C G. Plasma exudation and solute absorption across the airway mucosa. Clin Physiol. 1993;13:219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1993.tb00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvill E T, Cotter P A, Miller J F. Pregenomic comparative analysis between Bordetella bronchiseptica RB50 and Bordetella pertussis tohama I in murine models of respiratory tract infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6109–6118. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6109-6118.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvill E T, Cotter P A, Yuk M H, Miller J F. Probing the function of Bordetella bronchiseptica adenylate cyclase toxin by manipulating host immunity. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1493–1500. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1493-1500.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hitchcock P J, Brown T M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Blay K, Gueirard P, Guiso N, Chaby R. Antigenic polymorphism of the lipopolysaccharides from human and animal isolates of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microbiology. 1997;143:1433–1441. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesse A J, Campagnari A A, Bittner W E, Apicella M A. Increased resolution of lipopolysaccharides and lipooligosaccharides utilizing tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Immunol Methods. 1990;126:109–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90018-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ooi Y M, Colten H R. Genetic defect in secretion of complement C5 in mice. Nature. 1979;282:207–208. doi: 10.1038/282207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preston A, Allen A G, Cadisch J, Thomas R, Stevens K, Churcher C M, Badcock K L, Parkhill J, Barrell B, Maskell D J. Genetic basis for lipopolysaccharide O-antigen biosynthesis in bordetellae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3763–3767. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3763-3767.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preston A, Mandrell R E, Gibson B W, Apicella M A. The lipooligosaccharides of pathogenic gram-negative bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1996;22:139–180. doi: 10.3109/10408419609106458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai C M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turcotte M L, Martin D, Brodeur B R, Peppler M S. Tn5-induced lipopolysaccharide mutations in Bordetella pertussis that affect outer membrane function. Microbiology. 1997;143:2381–2394. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhl M A, Miller J F. Central role of the BvgS receiver as a phosphorylated intermediate in a complex two-component phosphorelay. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33176–33180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uhl M A, Miller J F. Integration of multiple domains in a two-component sensor protein: the Bordetella pertussis BvgAS phosphorelay. EMBO J. 1996;15:1028–1036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Akker W M. Lipopolysaccharide expression within the genus Bordetella: influence of temperature and phase variation. Microbiology. 1998;144:1527–1535. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-6-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Zee A, Mooi F, Van Embden J, Musser J. Molecular evolution and host adaptation of Bordetella spp.: phylogenetic analysis using multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and typing with three insertion sequences. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6609–6617. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6609-6617.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuk M H, Harvill E T, Cotter P A, Miller J F. Modulation of host immune responses, induction of apoptosis and inhibition of NF-kB activation by the Bordetella type III secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:991–1004. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuk M H, Harvill E T, Miller J F. The BvgAS virulence control system regulates type III secretion in Bordetella bronchiseptica. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:945–959. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]