Abstract

Immature mice are highly susceptible to blastomycosis, which is similar to other mycoses and has parallels in humans. The murine susceptibility is noteworthy in that it persists beyond the development of resistance to other, nonfungal pathogens and the maturation of most immune functions. As the susceptibility to blastomycosis appeared to be related to an early event after infection, primary effector cell function was studied. We found that peritoneal inflammatory cells, enriched for neutrophils, from immature (3-week-old) mice killed nonphagocytizable Blastomyces dermatitidis cells less (25%) than did cells from mature (8-week) mice (70%) (P < 0.01), a defect intrinsic to the neutrophils. This correlated with an impaired immature cell oxidative burst. Killing of phagocytizable Candida albicans was not significantly different, 73 versus 87%. Thioglycolate-elicited cells were more impaired; killing of B. dermatitidis was insignificant, and killing of C. albicans was more impaired in immature (16% killing) than in mature (45%) cells (P < 0.02). Peripheral blood neutrophils from mature animals killed B. dermatitidis (41%) more than did those from immature animals (10%) (P < 0.02); C. albicans was killed efficiently by both. Resting or activated peritoneal macrophages from both types of animals showed no differences in B. dermatitidis killing. These results suggest that the susceptibility of immature mice is related at least in part to the depressed capacity of their neutrophils to kill B. dermatitidis.

Previous studies from our laboratory have shown striking differences in the susceptibilities of immature and mature mice to blastomycosis (8). For example, for challenges via the pulmonary route, 5-week-old mice were 1,000-fold more susceptible than 9-week-old mice. This striking difference in susceptibility was not dependent on the route of challenge. Resistance developed progressively over age 3 to 10 weeks. Studies involving serial sacrifice of infected cohorts revealed that the infection-limiting event in older mice, i.e., the interval before infectious burdens began to diverge in the two age groups, occurred within 4 days of challenge (8). This timing suggested that the difference in the age groups rested in differences in nonspecific immunity, e.g., activity of effector cells, rather than specific humoral or lymphocyte-mediated immunity, which would require more time for its expression. The studies reported here address the possible mechanism of the age-related differences in immunity, by studying effector cell function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Sendai virus-free BALB/cByJIMR (California Institute for Medical Research, San Jose) male mice 3 and 8 weeks old were used throughout these experiments. The average body weights were 15 g for immature mice and 25 g for mature mice.

Fungi.

Blastomyces dermatitidis isolate ATCC 26199, a virulent isolate in mice (71), was used throughout these experiments. Yeast form B. dermatitidis from 72-h liquid medium cultures was used to inoculate blood agar plates. Forty-eight- to seventy-two-hour growth of B. dermatitidis on blood agar plates was used to prepare inocula for challenging phagocytic cell cultures. CFU per milliliter of inoculum was determined by plating appropriate dilutions on blood agar plates.

Candida albicans isolate Sh27 (19) (ATCC 56882) was grown in yeast nitrogen base broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 32°C from stock cultures stored on Sabouraud agar slants at 4°C. C. albicans cells grown in yeast nitrogen base broth for 3 days at 32°C were washed twice in saline and counted with a hemacytometer. The CFU per milliliter of inoculum was determined by plating 1 ml of appropriate dilution on blood agar plates.

Media and reagents.

Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (PBS), minimal essential medium (MEM), RPMI 1640, heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (10,000 U/ml), and streptomycin (10,000 μg/ml) were purchased from GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, N.Y. Complete tissue culture medium consisted of RPMI 1640, 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, and 100 U of penicillin plus 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Histopaque 1077, dextran 300 K, luminol, and concanavalin A (ConA) were obtained from Sigma Co., St. Louis, Mo. Sodium caseinate and thioglycolate liquid medium (BACTO-B256) (Difco Laboratories) were used in these studies.

Peripheral blood and serum.

Mice were anesthetized with ether, a pouch of skin was formed between a front leg and body torso by dissection, the brachial artery was severed, and blood was collected with a Pasteur pipette. When blood was used as a source of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), it was heparinized with preservative-free heparin (30 U/ml) on collection. Fresh mouse serum was collected from clotted blood and was shown previously to have complement activity in a cytotoxicity assay (11).

PEC-PMN.

Peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) enriched for PMN were induced by intraperitoneal injection of 1 ml of 2% sodium caseinate (Difco) or thioglycolate broth (Clinical Standards Laboratory, Carson, Calif.). Four hours later, peritoneal cells were collected by repeated lavage of the peritoneum of each mouse with a total of 10 ml of MEM containing 10 U of preservative-free heparin (American Scientific Products, McGaw Park, Ill.) per ml. PEC were fractionated by density gradient centrifugation on Histopaque 1077 (9), 400 × g for 30 min, at room temperature. The pelleted cells were further enriched for PMN by centrifugation in a metrizamide gradient, 400 × g for 20 min (15). These cells were washed once in MEM, suspended in complete tissue culture medium, and counted with a hemacytometer.

Peripheral blood PMN.

Peripheral blood PMN were obtained as follows: (i) layering heparinized blood diluted 1:1 in saline over an equal volume of Histopaque 1077; (ii) centrifugation at 900 × g for 20 min; (iii) suspension of pelleted red blood cells and PMN in an equal volume of saline; (iv) mixing suspended pelleted cells with an equal volume of 3% (wt/vol) dextran 300 in saline and incubating for 1 h at 37°C; (v) collection of buffy coat layers and pelleting of cells by centrifugation, 400 × g, 10 min; (vi) suspension of pelleted cells in 10 ml of 0.85% NH4Cl to lyse contaminating red blood cells; and (vii) washing of treated cells with MEM followed by suspension in complete tissue culture medium.

Peritoneal macrophages.

Resident and elicited peritoneal macrophages were induced by intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 ml of saline alone or containing 100 μg of ConA. Twenty-four hours later, peritoneal cells were collected by repeated peritoneal lavage with a total of 10 ml of MEM containing 10 U of preservative-free heparin per ml. After one wash in this medium, cells were suspended in complete tissue culture medium, counted in a hemacytometer, and dispensed (0.2 ml of 5 × 106 cells/ml) into flat-bottomed wells of 96-well tissue culture clusters (catalog no. 3596; Costar, Cambridge, Mass.). After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2–95% air for 2 h, nonadherent cells were aspirated from the wells and fresh medium was added and removed twice. When the number of the nonadherent cells was subtracted from the number of the incubated peritoneal cells, the average number of adherent cells per well was 5 × 105, 85% of them mononuclear.

Differential counts.

Pelleted cells were suspended in a drop of fresh mouse serum, and microscope slide smears were prepared. Dried smears were stained using the Diff-Quik staining protocol (American Scientific Products). One hundred cells per slide were counted at an ×1,000 magnification, and the percentages of PMN and mononuclear cells were recorded. The viability of cells in these studies was confirmed by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Treatment with anti-mouse granulocyte antibody.

A monoclonal antibody specific for murine granulocytes, a gift from Robert Coffman, DNAX, Palo Alto, Calif., was used in these studies. The specificity of this antibody for PMN was determined by DNAX and confirmed by cytotoxicity studies here (47). Briefly, 0.5 ml of 5 × 106 cells/ml was incubated with 0.5 ml of a 1:10 dilution of antibody in MEM at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 3.5 ml of Low-Tox rabbit complement (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, N.Y.), and diluted 1:10 in MEM. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in complete tissue culture medium for use in fungicidal assays.

Fungicidal assays with PMN.

PMN (0.1 ml of 5 × 106 PMN/ml in complete tissue culture medium) were dispensed into flat-bottomed Micro Test plate wells (Falcon 3072; Becton Dickinson Co., Oxnard, Calif.) and then challenged with 0.1 ml of B. dermatitidis (5,000 CFU/ml) or C. albicans (10,000 CFU/ml) in complete tissue culture medium. After fresh mouse serum (0.02 ml) was added to each coculture and control culture, they were incubated at 37°C for 2 h in 5% CO2–95% air. Cultures were harvested with distilled water as previously described (17) and plated on blood agar plates. CFU per culture was determined by counting CFU per plate after 2 days (C. albicans) or 4 to 5 days (B. dermatitidis) of incubation at 35°C. Percent reduction of inoculum CFU was calculated as [1 − (coculture CFU/inoculum CFU)] × 100.

Fungicidal assays of peritoneal macrophages.

Adherent cells in each well were challenged with 0.2 ml of tissue culture medium containing 500 CFU of B. dermatitidis, at 37°C in 5% CO2–95% air for 4 h. The content of each well was harvested into 8.8 ml of distilled water, then the wells were washed five times with 0.2 ml of distilled water, and pooled culture contents and washings (total, 10 ml) were plated on blood agar plates (1 ml/plate). CFU per culture was recorded after 4 or 5 days of incubation.

Chemiluminescence.

To detect the products of oxidative metabolism subsequent to challenge of PMN with fungi in fresh mouse serum, the luminol method of Allen and Loose was used (1). Briefly, 0.1 ml of PMN (107/ml of PBS), 0.1 ml of luminol solution (80 ng/ml), 0.05 ml of fresh mouse serum, and 0.15 ml of PBS were combined with 0.1 ml of fungal cells rendered nonviable by the effects of temperature, as previously described (46) (107 fungi/ml of PBS), at room temperature. Photon emission was measured in a scintillation counter (Mark II; Nuclear-Chicago Corp., Des Plaines, Ill.) at room temperature with the windows set on “manual” and levels set at L-infinity. The manual setting permitted rapid counting of samples, and the counts per minute were calculated by using the counting time (≤0.2 min) registered by the scintillation counter.

Statistical analysis.

Student's t test was used to determine the significance of differences between means, except where otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Fungicidal activity of caseinate-elicited PMN.

Most published data concerning rodent PMN function have utilized cells elicited in the peritoneal cavity. We studied such cells elicited by two different elicitants, caseinate and thioglycolate medium, and compared the activities of cells from mature and immature mice against both B. dermatitidis (not phagocytizable by a single host effector cell) (10) and C. albicans (a phagocytizable target).

We found that PEC enriched for PMN as induced by caseinate in mature mice significantly killed B. dermatitidis ([70 ± 20]%, n = 7; mean ± standard deviation, number of experiments) (Table 1). This was significantly different (P < 0.01) from the killing by caseinate-induced PMN of immature mice ([25 ± 27]%, n = 7). Killing by PMN from immature mice was thus more variable, but there was always a ≥20% difference in percent killed, in favor of mature mice, in each of seven concurrent experiments (P < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

TABLE 1.

Phagocyte fungicidal activitya

| Phagocyte | Host type | Elicitant | Target | Killing (mean ± SD; reduction of inoculum) | No. of expts | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEC (PMN) | Mature | Caseinate | B. dermatitidis | 70 ± 20 | 7 | <0.01 |

| PEC (PMN) | Immature | Caseinate | B. dermatitidis | 25 ± 27 | 7 | |

| PEC (PMN) | Mature | Caseinate | C. albicans | 87 ± 7 | 3 | NS |

| PEC (PMN) | Immature | Caseinate | C. albicans | 73 ± 15 | 3 | |

| PEC (PMN) | Mature | Thioglycolate | B. dermatitidis | 8 ± 7 | 4 | NS |

| PEC (PMN) | Immature | Thioglycolate | B. dermatitidis | 0 | 4 | |

| PEC (PMN) | Mature | Thioglycolate | C. albicans | 45 ± 17 | 5 | <0.02 |

| PEC (PMN) | Immature | Thioglycolate | C. albicans | 16 ± 12 | 5 | |

| PB-PMN | Mature | None | B. dermatitidis | 41 ± 18 | 5 | <0.02 |

| PB-PMN | Immature | None | B. dermatitidis | 10 ± 5 | 5 | |

| PB-PMN | Mature | None | C. albicans | 98 | 1 | NS |

| PB-PMN | Immature | None | C. albicans | 97 | 1 | |

| PB-Mono | Mature | None | B. dermatitidis | 0 | 1 | |

| PM | Mature | ConA | B. dermatitidis | 34 ± 19 | 5 | NS |

| PM | Immature | ConA | B. dermatitidis | 48 ± 12 | 5 | |

| PM | Mature | Saline | B. dermatitidis | 9 ± 12 | 5 | NS |

| PM | Immature | Saline | B. dermatitidis | 7 ± 12 | 5 |

Abbreviations: PB, peripheral blood; Mono, mononuclear cells; PM, peritoneal macrophages; NS, not significant. Further definitions of the cell populations are given in the text.

This difference was not explained by a different percent PMN in the PEC population between mature and immature mice. PEC from mature mice were 68% PMN, and those from immature mice were 70% PMN (mean of two experiments); the remaining cells in both groups were mononuclear.

We showed that the fungicidal activity in the PEC was due to PMN by treating the PEC with anti-PMN antibody plus complement. In this experiment, caseinate-induced PEC from mature mice killed 74% of B. dermatitidis cells; after treatment with anti-PMN antibody plus complement, killing was 0%. Prior studies have shown that this antibody plus complement does not impair macrophage killing of fungi (Candida) (9).

Further evidence that the differences in killing were intrinsic to the cells was demonstrated in three experiments by incubating PEC from immature animals in the exudate (supernatant after centrifugation) of mature animals for 1 h prior to challenge in vitro with B. dermatitidis; the ability of the immature cells to kill was not significantly affected by exposure to the exudate of mature animals (data not shown).

In contrast, caseinate-induced PEC of both mature and immature animals were efficient in killing C. albicans. The cells from mature animals killed (87 ± 7)% (n = 3), and those from immature animals killed (73 ± 15)% (n = 3). The greater killing by mature animals' cells was not significantly different from that by those of immature animals.

Fungicidal activity of thioglycolate-elicited PMN.

Cells elicited with thioglycolate gave different results. Killing of B. dermatitidis by PEC from mature animals was (8 ± 7)% (n = 4), and killing by PEC from immature animals was 0% (n = 4). Neither result was significant. In contrast, candidacidal activity of cells from mature animals ([45 ± 17]%, n = 5) was significantly greater (P < 0.02) than that of cells from immature animals ([16 ± 12]%, n = 5).

This difference was not explained by differences in percent PMN in the two PEC populations. The PEC from mature animals were 73% PMN, and those from immature animals were 69% PMN (mean of two experiments); the remainder were mononuclear.

The yield of PEC (and thus, PMN) per gram of body weight was not significantly different between mature and immature mice with either elicitant. The yield of PEC per gram with caseinate was 32 × 104 ± 15 × 104 for mature animals and 25 × 104 ± 17 × 104 for immature animals. With thioglycolate, the yields were 31 × 104 ± 20 × 104 and 22 × 104 ± 10 × 104, respectively.

Oxidative burst in PMN of mature and immature animals, as assayed by chemiluminescence.

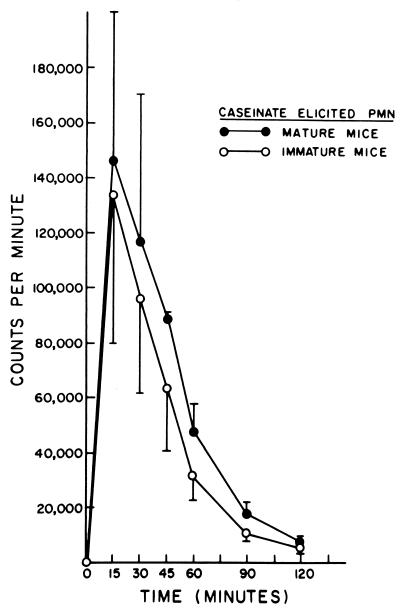

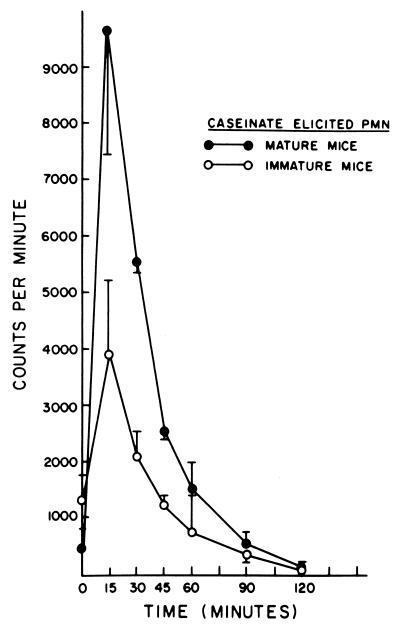

The mechanism of the differences in killing described was studied with caseinate-induced PEC and the chemiluminescence assay. As previously noted with cells from mature animals (19), chemiluminescence was found to be greater after challenge with C. albicans (Fig. 1) than with B. dermatitidis (Fig. 2), with cells of mature and immature animals. It was particularly noteworthy that, at the peak of the oxidative burst, at 15, 30, and 60 min, there was significantly less (P < 0.05, <0.001, and <0.001, respectively) chemiluminescence produced by cells of immature animals than by cells of mature animals in response to B. dermatitidis (Fig. 2). This difference correlates with the differences seen for killing of B. dermatitidis by these cells. In contrast, there were no significant differences in chemiluminescence between these cell populations after exposure to C. albicans (Fig. 1). This correlated with the lack of difference in killing of C. albicans between these groups.

FIG. 1.

Chemiluminescence produced by interaction of caseinate-elicited PMN from mature and immature mice with killed C. albicans.

FIG. 2.

Chemiluminescence produced by interaction of caseinate-elicited PMN from mature and immature mice with killed B. dermatitidis.

Peripheral blood PMN fungicidal activity.

Since the function of elicited PMN may be affected by the elicitant, we thought it important to also study a resting cell population, the peripheral blood PMN. Purified blood PMN from mature mice killed B. dermatitidis ([41 ± 18]%, n = 5) to a significantly (P < 0.02) greater extent than did those from immature mice ([10 ± 5]%, n = 5). The studies described above with caseinate-elicited cells showed greater variability in killing by the less active (immature) cell population, which may reflect the influence of the elicitant; thus, peripheral blood (unstimulated) cells may be a more appropriate cell population for study.

In contrast, purified blood PMN from both mature and immature mice were highly capable of killing C. albicans, with 98 and 97% killing, respectively. The potency of killing of C. albicans by peripheral blood PMN of mature mice has been previously reported (9).

The differences in killing B. dermatitidis were not due to differences in percent PMN in the preparations, as this was identical in preparations from mature and immature mice (82%, mean of two experiments each). The yield of peripheral blood leukocytes per gram of body weight was also not different, 1.5 × 104 ± 0.4 × 104 for mature mice and 1.1 × 104 ± 0.8 × 104 for immature mice.

Further evidence that the PMN are responsible for the fungicidal activity against B. dermatitidis described was provided by testing of the mononuclear cell fraction derived from peripheral blood leukocytes of mature animals. This fraction consisted of 85% mononuclear cells. No killing (0%) of B. dermatitidis was demonstrated by this fraction, in an experiment performed concurrently with the PMN (which killed 48%).

Effect of macrophages on B. dermatitidis.

Peritoneal macrophages elicited with ConA from immature or mature mice had significant fungicidal activity against B. dermatitidis, whereas saline-elicited macrophages did not. ConA-elicited and saline-elicited macrophages from mature mice killed 34% ± 19% and 9% ± 12%, respectively (P < 0.05), and with these cells from immature mice, killing was 48% ± 12% and (7 ± 12)%, respectively (P < 0.01) (n = 5 for each of the four groups). The differences between killing by ConA-elicited macrophages from mature mice and killing by such macrophages from immature mice were not significantly different, nor were the differences with saline-elicited macrophages. Thus, neither “activated” nor resting peritoneal macrophages were different in their fungicidal activity against B. dermatitidis, in a comparison of mature and immature mice.

DISCUSSION

The present studies suggest that the enhanced susceptibility of immature mice may relate to the depressed capacity of PMN from immature mice to kill B. dermatitidis. This may be best illustrated in our study of peripheral blood PMN, although a disparity in effector cell function was also seen with PMN from an inflammatory exudate, induced by casein. These differences between PMN of mature and immature mice were not seen with respect to the killing of C. albicans, as PMN from both sources were highly effective killers of C. albicans. These differences and similarities in killing between mature and immature cells with respect to these two targets were mirrored in the chemiluminescence studies, where there were mature-immature differences with B. dermatitidis as the target, but not with C. albicans. In contrast, thioglycolate-induced PMN were impaired with respect to killing of B. dermatitidis; this finding in mature cells plus the superior killing of B. dermatitidis by casein-induced compared to peripheral PMN by mature cells confirms earlier studies, performed only with mature animals (9). With the thioglycolate-impaired cells, a defect in killing, as prior work also suggested (18), became evident and extended even to C. albicans (9). These two fungi represent very different types of targets for effector cells; B. dermatitidis yeasts are larger (8- to 10-μm diameter) than C. albicans yeasts (2- to 4-μm diameter) and sometimes form clusters of two or three cells, whereas C. albicans yeasts can be easily phagocytosed (12). In short term (e.g., 2-h) cocultures, murine PMN kill B. dermatitidis; in longer-term (e.g., 24- to 72-h) cultures, viable or nonviable PMN may actually enhance B. dermatitidis multiplication (9, 14). Our finding of PMN deficiencies does not, however, exclude the possibility of additional immune defects, which have not been studied.

In contrast, macrophage killing by cells of immature mice was the same as that by cells of mature mice. Examination of peripheral blood monocytes for defects in cells of immature mice does not seem a productive avenue for research from these studies, as monocytes of mature animals were as incapable of killing B. dermatitidis as were resting (as opposed to ConA-induced) macrophages. Bronchoalveolar macrophages were not studied, not only because the disparity between immature and mature mouse susceptibilities to B. dermatitidis was not dependent on challenge by the respiratory route but also because resident bronchoalveolar macrophages of mature mice do not kill this fungus (16).

The present studies focused on resident or circulating cells, as well as those elicited in inflammatory exudates. PMN and macrophage killing of B. dermatitidis and other fungi can be up-regulated by cytokines, particularly gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (70), and it is possible that the relative efficacies of mature and of immature cells could be altered in vivo by differences in production of or responsiveness to cytokines or chemokines, and this could be studied in vitro. This is discussed further below.

The susceptibility of mice to blastomycosis extending as late into maturation as described previously (8) is in contrast to some other infections, where resistance has developed fully by as little as 2 weeks of age, on up to 5 weeks, e.g., for infection with Klebsiella strains (55), measles virus (52), hepatitis virus (75), Sindbis virus (26, 27, 31), herpes simplex virus type 1 (encephalitis) (45), K virus (25), and coronavirus (56). In contrast, development of resistance to herpes simplex virus type 2 (hepatitis) follows a time course similar to that for blastomycosis (45), and more relevant, less extensive studies have suggested similar time courses for aspergillosis (22), candidosis (64), and paracoccidioidomycosis (13).

With respect to referring to mice 3 to 5 weeks of age as “immature,” it should be noted that the period of development of resistance to blastomycosis overlaps the interval, from 4 (33) to 8 (45) weeks, of sexual maturation of the mouse. A hormonal influence on resistance needs to be explored in vitro and in vivo. However, many murine immune functions are fully developed before this time, such as the mitogenic response to lipopolysaccharide or pneumococcal polysaccharides (by 1 to 2 weeks of age) (59, 60), antibody formation to these (60) and other thymus-independent antigens (by 1 to 2 weeks) (49, 60), a complete set of B-cell markers (1.5 weeks) (66), and in some reports mitogenic response to ConA (3 weeks) (73) or phytohemagglutinin (6 weeks) (73). Neonatal mouse macrophages generally function normally as effector cells but not as antigen-presenting cells (36). Macrophage superoxide generation is fully developed by 4 weeks (44). Peritoneal macrophages were maximally responsive to mycobacterial infection by 4 weeks, and the lymphoid system was fully developed (78), and macrophage anti-Listeria activity developed by 4 weeks (53). Blastogenesis or antibody formation to thymus-dependent antigens develops over 4 to 8 weeks (60), and lymphocyte-mediated natural cytotoxicity peaks by age 5 to 8 weeks (28). In contrast, other immune functions develop later, such as blastogenesis to staphylococcal antigen (8 weeks) (59), and some reports of blastogenesis to phytohemagglutinin and ConA (8 weeks) (59), and the T-cell influence on antibody to pneumococcal antigen converts from the suppressor to helper mode by only 8 to 10 weeks of age (48). Some of the immune deficiencies in immature animals have been ascribed to suppressor mechanisms, though the suppressor activity is reversed before the period where mice remain susceptible to blastomycosis. For example, suppression of contact sensitivity has disappeared by age 5 days (67), suppression of primary and secondary antibody responses has disappeared by age 3 weeks (20, 23), non-T-cell suppressors of alloreactivity have disappeared by age 6 days (63), T-cell suppression of mixed lymphocyte cultures has disappeared by 3 weeks (4), and suppression of blastogenesis has disappeared by 4 weeks (37). Suppression of interleukin 2 (IL-2) production lasted until age 6 weeks (5).

Undoubtedly the best-studied immature animal, immunologically, is the human infant, and there are reports describing defects in almost every aspect of the immune system (30). In particular, PMN have previously described defects in adherence, aggregation, movement (30), phagocytosis or microbicidal activity in relation to some targets (of particular note, Candida [2, 30]), signal transduction, cell surface receptor up-regulation and mobility, specific granule content, cytoskeletal flexibility, microfilament contraction, chemiluminescence, oxygen metabolism (some studies), defense against auto-oxidative cell damage (30), chemiluminescence (74), storage pool size (58), chemotactic factor binding and hydroxyl radical generation (76), lactoferrin release (3), and myeloperoxidase (62). The susceptibility of neonates to candidiasis suggests the primacy of a PMN defect. Other immune defects include humoral immunity: decreased B cells of the plasma cell type (50) and immunoglobulins (58) and the presence of plasma factors that depress phagocytosis and H2O2 generation (24); T-cell immunity (72): defective T-cell cytotoxicity (50), lymphotoxin production (54), and lymphocytic antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (51), though lymphocyte production of chemotaxins is normal (54); NK cell function (76); and complement (58), with opsonization depressed via the alternate but not the classical pathway (39). Relevant to Table 1, infant macrophages generally function normally, though they are less responsive to neonatal cytokines (76) and less functional as accessory cells for antibody production (54). Their phagocytosis is normal (69), including that by bronchoalveolar macrophages (65), though the latter have depressed microbicidal activity. Macrophage killing of Candida is intact, although the cells are less responsive to enhancement by IFN-γ (38). Similarly, infant monocytes have generally normal function (6), with intact nitroblue tetrazolium reduction (43), respiratory burst (68), intracellular killing (43), and secretion of lysozyme (43), though studies of their chemotaxis (41, 43), phagocytosis (40, 41, 43), and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (7, 43, 54) have given variable results, and their adherence is reportedly depressed (58). Of possible particular relevance to our findings, abnormalities in PMN and monocyte chemotaxis have been reported to persist to age 2 to 5 years (32). Moreover, infant PMN defects with respect to Candida may relate to cell movement abnormalities, since a pseudopod must be developed in an attempt to surround the target (30), a problem which would be magnified for Blastomyces. In addition, we have shown previously (10) that effector cell migration to the large B. dermatitidis targets in vitro is the first step in their interaction, and this could be impaired by abnormalities in cell flexibility or chemotaxis. Finally, PMN bactericidal defects have been magnified in stressed (e.g., infected) neonates (30), and so it is possible that the baseline defects that we describe would be magnified in infected animals.

In addition, cytokine production or responsiveness abnormalities in human neonates are described elsewhere, particularly in IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (77), and IL-4 (35), though the IL-2 system is largely intact (35). The IFN-γ findings may be particularly relevant, since we previously have shown that IFN-γ up-regulates PMN (47) and macrophage (12) killing of Blastomyces, and a putative IFN-γ defect in immature mice might exaggerate the baseline PMN defect described in the present study. On the other hand, the fact that the responsiveness of naive mature animals to blastomycosis occurs in <4 days (8), as previously mentioned, speaks against the involvement of cytokines dependent on the development of immunological memory. The therapeutic or prophylactic study of cytokines may provide an avenue of prospects for therapy (29) that might be applied in the future in this model.

The susceptibility of immature mice to Blastomyces is likely relevant to, in humans, not only the well-described problems of candidiasis in infancy (42) and the severity of acute pulmonary blastomycosis in children (57), but also the association of acute progressive histoplasmosis with childhood (21), increased dissemination of coccidioidomycosis in childhood (34), and association of the acute form of paracoccidioidomycosis with the young (61). The murine model of blastomycosis may thus prove useful for the study of the maturation of defenses against, in particular, extracellular targets, such as some fungi, some parasites, and tumor cells.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen R C, Loose L D. Phagocytic activation of luminol-dependent chemiluminescence in rabbit alveolar and peritoneal macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;69:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(76)80299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambruso D R, Altenburger K M, Johnston R B., Jr Defective oxidative metabolism in newborn neutrophils: discrepancy between superoxide anion and hydroxyl radical generation. Pediatrics. 1979;64(Suppl.):722–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson D C. Neonatal neutrophil dysfunction. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1989;11:224–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argyris B F. Further studies on suppressor cell activity in the spleen of neonatal mice. Cell Immunol. 1979;48:398–406. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(79)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argyris B F, DeStefano M, Zamkoff K W. Interleukin-2 production in the neonatal mouse. Transplantation. 1985;40:284–287. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198509000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman J D, Johnson W D., Jr Monocyte function in human neonates. Infect Immun. 1978;19:898–902. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.3.898-902.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaese R M, Poplack D G, Muchmore A V. The mononuclear phagocyte system: role in expression of immunocompetence in neonatal and adult life. Pediatrics. 1979;64(Suppl.):829–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brass C, Stevens D A. Maturity as a critical determinant of resistance to fungal infections: studies in murine blastomycosis. Infect Immun. 1982;36:387–395. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.1.387-395.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brummer E, McEwen J G, Stevens D A. Fungicidal activity of murine inflammatory polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN): comparison with murine peripheral blood PMN and human peripheral blood PMN. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;66:681–690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brummer E, Morozumi P A, Philpott D E, Stevens D A. Virulence of fungi: correlation of virulence of Blastomyces dermatitidis in vivo with escape from macrophage inhibition of replication in vitro. Infect Immun. 1981;32:864–871. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.864-871.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brummer E, Morozumi P A, Vo P T, Stevens D A. Protection against pulmonary blastomycosis. II. Adoptive transfer with T lymphocytes, but not serum, from mice rendered resistant by resolution of a subcutaneous nonlethal infection. Cell Immunol. 1982;73:349–359. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(82)90461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brummer E, Morrison C J, Stevens D A. Recombinant and natural gamma-interferon activation of macrophages in vitro; different dose requirements for induction of killing activity against phagocytizable and nonphagocytizable fungi. Infect Immun. 1985;49:724–730. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.724-730.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brummer E, Restrepo A, Stevens D A, Azzi R, Gomez A M, Hoyos G L, McEwen J G, Cano L E, de Bedout C. A murine model of paracoccidioidomycosis: production of fatal acute pulmonary or chronic pulmonary-disseminated disease using young mice, immunological and pathological observations. J Exp Pathol. 1984;1:241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brummer E, Stevens D A. Effect of murine polymorphonuclear neutrophils on the multiplication of Blastomyces dermatitidis in vitro and in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;54:587–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brummer E, Stevens D A. Activation of murine polymorphonuclear neutrophils for fungicidal activity with supernatants from antigen-stimulated immune spleen cell cultures. Infect Immun. 1984;45:447–452. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.2.447-452.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brummer E, Stevens D A. Activation of pulmonary macrophages for fungicidal activity by gamma interferon or lymphokines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;70:520–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brummer E, Sugar A M, Stevens D A. Activation of peritoneal macrophages by concanavalin A or Mycobacterium bovis BCG for fungicidal activity against Blastomyces dermatitidis and effect of specific antibody and complement. Infect Immun. 1983;39:817–822. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.817-822.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brummer E, Sugar A M, Stevens D A. Immunological activation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils for fungal killing: studies with murine cells and Blastomyces dermatitidis. J Leukoc Biol. 1984;36:505–520. doi: 10.1002/jlb.36.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brummer E, Sugar A M, Stevens D A. Enhanced oxidative burst in immunologically activated, but not elicited, polymorphonuclear leukocytes correlates with fungicidal activity. Infect Immun. 1985;49:396–401. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.396-401.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calkins C E, Stutman O. Changes in suppressor mechanisms during postnatal development in mice. J Exp Med. 1978;147:87–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christie A. Disease spectrum of human histoplasmosis. Ann Intern Med. 1958;49:544–555. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-49-3-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbel M J, Eades S M. Examination of the effect of age and acquired immunity on the susceptibility of mice to infection with Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycopathologia. 1977;60:79–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00490376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeKruyff R H, Kim Y T, Siskind G W, Weksler M E. Age related changes in the in vitro immune response: increased suppressor activity in immature and aged mice. Immunology. 1980;125:142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujiwara T, Kobayashi T, Takaya J, Taniuchi S, Kobayashi Y. Plasma effects on phagocytic activity and hydrogen peroxide production by polymorphonuclear leukocytes in neonates. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;85:67–72. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenlee J E. Effect of host age on experimental K virus infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1981;33:297–303. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.1.297-303.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin D E. Role of the immune response in age-dependent resistance of mice to encephalitis due to Sindbis virus. J Infect Dis. 1976;133:456–464. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hackbarth S E, Reinarz A B G, Sagik B P. Age-dependent resistance of mice to Sindbis virus infection: reticuloendothelial role. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1973;14:405–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herberman R B, Nunn M E, Lavrin D H. Natural cytotoxic reactivity of mouse lymphoid cells against syngeneic and allogeneic tumors. I. Distribution of reactivity and specificity. Int J Cancer. 1975;16:216–229. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910160204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill H R. Host defenses in the neonate: prospects for enhancement. Semin Perinatol. 1985;9:2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill H R. Biochemical, structural, and functional abnormalities of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the neonate. Pediatr Res. 1987;22:375–382. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198710000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson R T, McFarland H F, Levy S E. Age-dependent resistance to viral encephalitis: studies of infections due to Sindbis virus in mice. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:257–262. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein R B, Fischer T J, Gard S E, Biberstein M, Rich K C, Stiehm E R. Decreased mononuclear and polymorphonuclear chemotaxis in human newborns, infants and young children. Pediatrics. 1977;60:467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krzych U, Thurman G B, Goldstein A L, Bressler J P, Strausser H R. Sex-related immunocompetence of BALB/c mice. I. Study of immunologic responsiveness of neonatal, weanling, and young adult mice. J Immunol. 1979;123:2568–2574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavetter A. Coccidioidomycosis in pediatrics. In: Stevens D A, editor. Coccidioidomycosis: a text. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1980. pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis D B, Yu C C, Meyer J, English B K, Kahn S J, Wilson C B. Cellular and molecular mechanisms for reduced interleukin 4 and interferon-γ production by neonatal T cells. J Clin Investig. 1991;87:194–202. doi: 10.1172/JCI114970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu C Y, Unanue E R. Ontogeny of murine macrophages: functions related to antigen presentation. Infect Immun. 1982;36:169–175. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.1.169-175.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maier T, Holda J H. Natural suppressor (NS) activity from murine neonatal spleen is responsive to IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1987;138:4075–4084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maródi L, Káposta R, Campbell D E, Polin R A, Csongor J, Johnston R B., Jr Candidacidal mechanisms in the human neonate. Impaired IFN-γ activation of macrophages in newborn infants. J Immunol. 1994;153:5643–5649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maródi L, Leijh P C J, Braat A, Daha M R, van Furth R. Opsonic activity of cord blood sera against various species of microorganism. Pediatr Res. 1985;19:433–436. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maródi L, Leijh P C J, van Furth R. Characteristics and functional capacities of human cord blood granulocytes and monocytes. Pediatr Res. 1984;18:1127–1131. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198411000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller M E. Phagocyte function in the neonate: selected aspects. Pediatrics. 1979;64:709–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller M J. Fungal infections. In: Remington J S, Klein J O, editors. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1976. pp. 637–690. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mills E L. Mononuclear phagocytes in the newborn: their relation to the state of relative immunodeficiency. Am J Hematol Oncol. 1983;5:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitsuyama M, Ohara R, Amako K, Nomoto K, Yokokura T, Nomoto K. Ontogeny of macrophage function to release superoxide anion in conventional and germfree mice. Infect Immun. 1986;52:236–239. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.236-239.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mogensen S C. Macrophages and age-dependent resistance to hepatitis induced by herpes simplex virus type 2 in mice. Infect Immun. 1978;19:46–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.1.46-50.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrison C J, Brummer E, Stevens D A. Effect of a local immune reaction on peripheral blood polymorphonuclear neutrophil microbicidal functions: studies with fungal targets. Cell Immunol. 1987;110:176–182. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(87)90111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morrison C J, Stevens D A. Enhanced killing of Blastomyces dermatitidis by gamma interferon-activated murine peripheral blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1989;11:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(89)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morse H C, Prescott B, Cross S S, Stashak P W, Baker P J. Regulation of the antibody response to type III pneumococcal polysaccharide. V. Ontogeny of factors influencing the magnitude of the plaque-forming cell response. J Immunol. 1976;116:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mosier D E, Johnson B M. Ontogeny of mouse lymphocyte function. II. Development of the ability to produce antibody is modulated by T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1975;141:216–226. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagaoki T, Miyawaki T, Ciorbaru R, Yachie A, Uwandana N, Moriya N, Taniguchi N. Maturation of B cell differentiation ability and T cell regulatory function during child growth assessed in a Nocardia water soluble mitogen driven system. J Immunol. 1981;126:2015–2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nair M P N, Schwartz S A, Menon M. Association of decreased natural and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity production of natural killer cytotoxic factor in neonates and interferon in neonates. Cell Immunol. 1985;94:159–171. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(85)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neighbour P A, Rager-Zisman B, Bloom B R. Susceptibility of mice to acute and persistent measles infection. Infect Immun. 1978;21:764–770. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.3.764-770.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohara R, Mitsuyama M, Miyata M, Nomoto K. Ontogeny of macrophage-mediated protection against Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1985;48:763–768. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.3.763-768.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pabst H F, Kreth H W. Ontogeny of the immune response as a basis of childhood disease. J Pediatr. 1980;97:519–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parant M, Parant F, Chedid L. Enhancement of the neonate's nonspecific immunity to Klebsiella infection by muramyl dipeptide, a synthetic immunoadjuvant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3395–3399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pickel K, Müller M A, ter Meulen V. Analysis of age-dependent resistance to murine coronavirus JHM infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1981;34:648–654. doi: 10.1128/iai.34.3.648-654.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powell D A, Schmit K E. Acute pulmonary blastomycosis in children: clinical course and followup. Pediatrics. 1979;63:736–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quie P G. Antimicrobial defenses in the neonate. Semin Perinatol. 1990;14(Suppl. 1):2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rabinowitz S G. Comparative mitogenic responses of T-cells and B-cells in spleens of mice of varying age. Immunol Commun. 1975;4:63–79. doi: 10.3109/08820137509055762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rabinowitz S G. Measurement and comparison of the proliferative and antibody responses of neonatal, immature and adult murine spleen cells to T-dependent and T-independent antigens. Cell Immunol. 1976;21:201–216. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(76)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Restrepo A, Robledo M, Giraldo R, Hernandez H, Sierra F, Gutierrez F, Londono F, Lopez R, Calle G. The gamut of paracoccidioidomycosis. Am J Med. 1976;61:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rider E D, Christensen R D, Hall D C, Rothstein G. Myeloperoxidase deficiency in neutrophils of neonates. J Pediatr. 1988;112:648–651. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodriguez G, Andersson G, Wigzell H, Peck A B. Non-T cell nature of the naturally occurring, spleen-associated suppressor cells present in the newborn mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1979;9:737–746. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salvin S B, Cory J C, Berg M K. The enhancement of the virulence of Candida albicans in mice. J Infect Dis. 1952;90:177–182. doi: 10.1093/infdis/90.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shigeoka A O, Santos J I, Hill H R. Functional analysis of neutrophil granulocytes from healthy, infected, and stressed neonates. J Pediatr. 1979;95:454–460. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sidman C L, Unanue E R. Development of B lymphocytes. I. Cell populations and a critical event during ontogeny. J Immunol. 1975;114:1730–1735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Skowron-Cendrzak A, Ptak W. Splenic suppressor cells in fetal and newborn mice. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 1976;26:1091–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Speer C P, Ambruso D R, Grimsley J, Johnston R B., Jr Oxidative metabolism in cord blood monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect Immun. 1985;50:919–921. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.3.919-921.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Speer C P, Gahr M, Wieland M, Eber S. Phagocytosis-associated functions in neonatal monocyte-derived macrophages. Pediatr Res. 1988;24:213–216. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198808000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stevens D A, Brummer E. Cytokines and the host-fungal interplay. In: Vanden Bossche H, Odds F C, Stevens D A, editors. Host-fungus interplay. Bethesda, Md: National Foundation for Infectious Diseases; 1997. pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stevens D A, Brummer E, DiSalvo A F, Ganer A. Virulent isolates and mutants of Blastomyces in mice: a legacy for studies of pathogenesis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stiehm E R, Winter H S, Bryson Y J. Cellular (T cell) immunity in the human newborn. Pediatrics. 1979;64(Suppl.):814–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stobo J D, Paul W E. Functional heterogeneity of murine lymphoid cells. II. Acquisition of mitogen responsiveness and of theta antigen during the ontogeny of thymocytes and T lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1972;4:367–380. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(72)90039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Strauss R G, Rosenberger T G, Wallace P D. Neutrophil chemiluminescence during the first month of life. Acta Haematol. 1980;63:326–329. doi: 10.1159/000207430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tardieu M, Hery C, Dupuy J M. Neonatal susceptibility to MHV3 infection in mice. II. Role of natural effector marrow cells in transfer. Immunology. 1980;124:418–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilson C B. Immunologic basis for increased susceptibility of the neonate to infection. J Pediatr. 1986;108:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson C B, Lewis D B. Basis and implications of selectively diminished cytokine production in neonatal susceptibility to infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(Suppl. 4):S410–S420. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_4.s410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang H Y, Skinsnes O K. Peritoneal macrophage response in neonatal mice. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1973;14:181–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]