Abstract

Aims

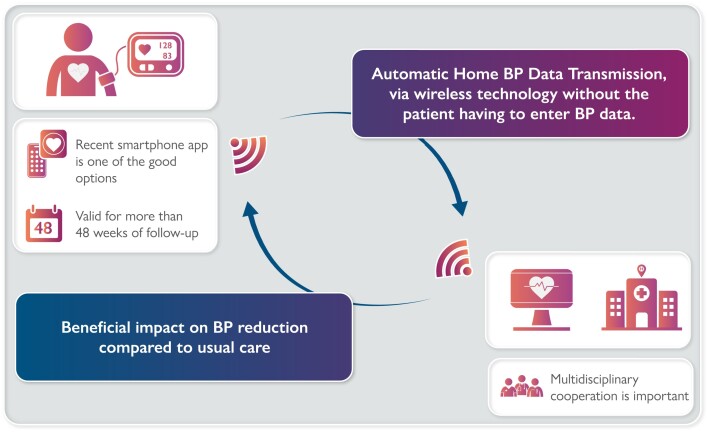

Home blood pressure telemonitoring (HBPT) is a useful way to manage BP. Recent advances in digital technology to automatically transmit BP data without the patient input may change the approach to long-term BP treatment and follow-up. The purpose of this review is to summarize the latest data on the HBPT with automatic data transmission.

Methods and results

Articles in English from 1980 to 2021 were searched by electronic databases. Randomized controlled trials comparing HBPT with automatic data transmission with usual BP management and including systolic BP (SBP) and/or diastolic BP (DBP) as outcomes in hypertension patients were included in the systematic review. A meta-analysis was conducted. After removing duplicates, 474 papers were included and 23 papers were identified. The HBPT with automatic data transmission had a significant beneficial impact on BP reduction (mean difference for office SBP −6.0 mm Hg; P < 0.001). Subgroup analyses showed that the studies using smartphone applications reduced BP significantly more in the intervention group than in the control group (standardized mean difference for office and home SBP −0.25; P = 0.01) as did the studies using HBPT other than the applications. Longer observation periods showed a sustained effect, and multidisciplinary cooperation was effective.

Conclusion

This review suggests that a care path based on HBPT with automatic data transmission can be more effective than classical management of hypertension. In particular, the studies using smartphone applications have shown beneficial effects. The results support the deployment of digital cardiology in the field of hypertension management.

Keywords: Hypertension, Telemonitoring, Automatic, Prevention, Digital health, e-Cardiology

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the biggest global concerns in cardiovascular disease. Adequate blood pressure (BP) control has been reported in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guideline in 20211 to reduce future morbidity and mortality, and its management is important for all aspects of cardiology. Home BP (HBP) monitoring is superior to office BP (OBP) monitoring because it has more value in predicting cardiovascular outcomes.2 The ESC and ESH guideline also indicates that telemonitoring and smartphone applications of HBPs may be even more beneficial. In general, there are several methods for ‘telemonitoring’ of HBP. For example, self-measured BP information was shared over the telephone in the 1990s. Digital cardiology has made remarkable progress in recent years,3 and nowadays, a single press of a button on the screen of a smart device can automatically transmit a patient’s BP data to healthcare providers. Although telemonitoring system with automatic BP data transmission has potential limitations such as the wide heterogeneity of devices/applications, the economic considerations, and the workload on the healthcare providers, it is easier to use than manual BP transmission and saves patients the trouble of recording their own BP data and reporting phantom BP records.4 It has also been reported that patients who have had their HBP measured many times often report the lowest BP data.5 Therefore, the more data and the longer a patient measures HBP, the more advantageous the automatic BP data transmission system will be. In addition, a smartphone application can be used to automatically notify abnormal BP values or track parameters other than BP with simple operations.6 The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to summarize the latest data on the utility of HBP telemonitoring (HBPT) systems, with a focus on the automatic transmission of BP data by digital devices.

Methods

Data sources and search

The search was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.7 PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase databases were searched for studies published between 1980 and October 2021. The search was performed iteratively for synonyms of ‘hypertension’, ‘home blood pressure’, and ‘telemonitoring’ using controlled vocabulary (e.g. MeSH or Emtree) and free text words (see Supplementary material online, S1). Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included adults older than 20 years old were included in the study. The reference lists and the referred articles of the identified relevant papers (including reviews) were cross-checked to find additional references.

Study selection

This review included full-length articles published in peer-reviewed journals. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: (i) describing an RCT written in English; (ii) (most of) patients must have been diagnosed with hypertension; (iii) comparing an HBPT system that automatically transmitted BP data after the measurement to a usual BP management without this system; and (iv) describing at least one of the following outcomes comparing pre- and post-intervention: systolic BP (SBP) or diastolic BP (DBP). Regarding (iii), ‘telemonitoring with automatic data transmission’ meant that measured BP data would be transmitted to a digital device via wireless technology (e.g. telephone line, Bluetooth) without the patient having to enter BP data. The system of entering BP data manually into an online system, an email, a memo, or using a telephone is excluded because they are not ‘automatic’. Two researchers (T.K. and V.I.-G.) checked the titles and abstracts of all identified papers. All duplicates were excluded. If there was doubt about eligibility, articles were read in full. A third investigator (M.S.) resolved differences in decision-making. The selection process was based on the PRISMA guideline.7

Data extraction

For each selected RCT, the first physician (T.K.) completed the data extraction. It included authors, year of publication, country of the study, number of patients including patient characteristics, RCT achievement rate, and details of dropouts. In addition, the type of device used, the duration of the study from randomization to the end of the follow-up period, the duration of the HBPT intervention, and the nature of the HBPT and other interventions were extracted. Eventually, outcome data on changes in SBP and DBP were collected. When results from more than one follow-up period were presented in a single RCT, the one with the same follow-up period as the intervention period was selected. If there were papers that reported only the long-term follow-up results after the intervention of an original paper, only the original paper was retained. The corresponding authors of the retained papers were contacted to supplement the missing information. The selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram of the study selection strategy.

Study quality

Two researchers (T.K. and V.I.-G.) individually assessed the risk of bias in the included articles, and a third investigator (M.S.) compared the results. The risk of methodological bias in these studies was checked according to the parameters of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.8 Each parameter is scored as high, low, or unclear risk of bias. If the risk of random sequence generation or allocation concealment was high, the risk of bias was determined to be at high.

Data synthesis and statistical analyses

A meta-analysis using Review Manager Version 5.4 for Windows (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) was conducted to examine the effect of HBPT with automatic data transmission on hypertension. The differences between the two comparative groups (with vs. without an HBPT with automatic data transmission system) were examined. Effect sizes [risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI)] were calculated for SBP and DBP. Random-effects modelling was used because studies vary in duration, delivery, and evaluation. Heterogeneity was assessed by Q-statistics, and I2 > 75% was considered high heterogeneity.9 All tests were performed at the 5% level of significance; for SBP and DBP, the mean change from baseline and standard deviation (SD), if available, were used. For trials that did not report SD of change in outcomes,10–15 values were imputed by a validated strategy16 (Supplementary material online, S2).

Results

Study characteristics

Fifty-three full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 17 RCTs10,11,13,15,17–29 that met the inclusion criteria were selected. Six more RCTs12,14,30–33 were extracted from the references (Table 1). A total of 5 743 patients were included in the 23 RCTs. Seven studies were from Europe (Denmark,13,30 Germany,12 UK,11,27,33 and Italy28), 11 were from the USA10,14,15,19–21,24,26,29,31,32 and 1 was from Canada,25 and 4 were from Asia (Japan17,18,23 and Korea22). The percentage of male patients ranged from 11.5 to 95.3%, and the average age ranged from 48 to 68 years. The sample size ranged from 26 to 593. One hundred per cent of hypertension patients were included in the studies other than one study.32 Details of the patient characteristics including outcome measures are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Articles (year), country | Patients’ diagnosis | No. of randomized patients | Male, % | Mean age, years | Patients who complete the study, % | Intervention durationa of HBP telemonitoring, weeks | Scheduled study visits after enrolment | Outcome measures | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kario et al.17 (2021), Japan | HT | 390 | 80.0 | 52 | 93.8 (366/390) | 24 | Every 4 weeks | OBP, HBP, ABPM | 24 h SBP changes |

| Kario et al.18 (2021), Japan | HT | 151 | 67.1 | 57 | 92.7 (140/151) | 24 | At 12, 16, and 24 weeks | OBP, HBP, ABPM | 24 h SBP changes |

| Lakshminarayan et al.19 (2018), USA | Stroke and HT | 56 | 67.9 | 65 | 89.3 (50/56) | 12b | Not shown | OBP | Usability and feasibility of mHealth technology |

| Morawski et al.20 (2018), USA | HT | 412 | 39.9 | 52 | 88.1 (363/412) | 12 | Every 4 weeks | HBP | Medication adherence changes; home SBP changes |

| Hoffmann-Petersen et al.30 (2017), Denmark | HT | 375 | 54.5 | 60 | 94.9 (356/375) | 12 | At 12 weeks | ABPM | Daytime ABPM changes |

| Kim et al.22 (2015), Korea | HT | 374 | 58.0 | 57 | 88.5 (331/374) | 24 | Every 8 weeks | OBP, ABPM | Office SBP changes |

| Davidson et al.31 (2015), USA | HT | 50 | 39.5 | 48 | 76.0 (38/50) | 24 | At 4, 12, and 24 weeks | OBP | Percentage of patients who achieved the target SBP |

| Kaihara et al.23 (2014), Japan | HT | 58 | 35.1 | 64 | 98.3 (57/58) | 4 | At 2 and 4 weeks | HBP | HBP changes |

| Wakefield et al.32 (2014), USA | T2DM | 108 | 44.4 | 60 | 76.9 (83/108) | 12 | At 12 weeks | OBP | SBP and HbA1c changes |

| Margolis et al.21 (2013), USA | HT | 450 | 55.3 | 61 | 86.2 (388/450) | 48 | At 24 and 48 weeks | OBP | Percentage of patients who achieved the target OBP |

| Magid et al.24 (2013), USA | HT | 348 | 60.3 | 60 | 93.7 (326/348) | 24 | At 24 weeks | OBP | Percentage of patients who achieved the target OBP |

| Rifkin et al.10 (2013), USA | Stage 3 or greater CKD and HT | 47 | 95.3 | 68 | 91.5 (43/47) | 24 | At 24 weeks | OBP | Improved BP data exchange and device acceptability |

| McKinstry et al.11 (2013), UK | HT | 401 | 59.1 | 61 | 95.5 (383/401) | 24 | At 24 weeks | ABPM | Daytime ambulatory SBP changes |

| Logan et al.25 (2012), Canada | DM and HT | 110 | 55.5 | 63 | 94.5 (104/110) | 48 | At 48 weeks | HBP, ABPM | Daytime ambulatory SBP changes |

| Neumann et al.12 (2011), Germany | HT | 60 | 50.9 | 55 | 95.0 (57/60) | 12 | At 12 weeks | ABPM | ABPM changes |

| Bosworth et al.26 (2011), USA | HT | 593 | 91.7 | 64 | 84.8 (503/593) | 72 | At 24, 48, and 72 weeks | OBP | Percentage of patients who achieved the target OBP |

| McManus et al.27 (2010), UK | HT | 527 | 46.9 | 66 | 91.1 (480/527) | 48 | At 24 and 48 weeks | OBP | Office SBP changes |

| Earle et al.33 (2010), UK | DM and HT | 137 | unknown | 58 | 69.3 (95/137) | 24 | At 24 weeks | OBP | OBP changes |

| Parati et al.28 (2009), Italy | HT | 329 | 54.4 | 58 | 87.5 (288/329) | 24 | At 1, 4, 12, and 24 weeks | OBP, ABPM | Percentage of patients who achieved the target daytime ABPM |

| Madsen et al.13 (2008), Denmark | HT | 236 | 50.4 | 56 | 94.5 (223/236) | 24 | At 24 weeks | ABPM | Daytime ambulatory SBP changes |

| Artinian et al.14 (2007), USA | HT | 387 | 35.7 | 60 | 86.8 (336/387) | 48 | At 12, 24, and 48 weeks | OBP | OBP changes |

| Artinian et al.15 (2001), USA | HT | 26 | 11.5 | 59 | 80.8 (21/26) | 12 | At 12 weeks | OBP | OBP changes |

| Rogers et al.29 (2001), USA | HT | 121 | 49.6 | 61 | 91.7 (111/121) | 11c | At 6–7 weeks | ABPM | ABPM changes |

HT, hypertension; BP, blood pressure; SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; HBP, home BP; OBP, office BP; ABPM, ambulatory BP monitoring; PP, pulse pressure; mHealth, mobile health; DM, diabetes mellitus; T2DM, Type 2 DM; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

One month was considered as 4 weeks.

If BP control was not achieved in some patients in the intervention group, extended monitoring for up to 6 months was allowed.

Patients in the intervention group were asked to participate in the intervention for a minimum of 8 weeks and could extend the intervention if they wished. The median time from baseline to the end of the study was 11 weeks.

Characteristics of the intervention for home blood pressure telemonitoring with automatic data transmission

In the included studies, HBPT devices (and other devices) with the capability of automatic transmission of BP data and feedback systems were used in the intervention group during the study period (Table 2). Most of the studies used HBPT devices with phone lines or Bluetooth wireless technology to transmit BP data. More recent studies17–20,25,31 reported the use of a smartphone application. In addition to transmitting BP data, 10 studies, including the majority of studies using smartphones, provided automatic feedback (BP reports as well as advice and alerts) to patients without intervention from healthcare professionals, and 20 studies used monitored BP data to provide feedback from healthcare professionals during the study periods. The application can also provide patients with a variety of alerts regarding BP and medications. One application used personalized motivational reminders,31 and the other included personalized interactive education programmes and interventions to implement lifestyle modifications.17 Non-physician healthcare providers participated as advisors to the telemonitoring system (Supplementary material online, S3). Nurses were the most integrated into the intervention protocol,11,14,15,19,22,26,28,31,32 and pharmacists were the second.10,19,21,24 Details of the pre-specified treatment protocols specific to the intervention group are summarized in Table 3. The interventions were categorized as pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacotherapy. Table 3 shows that most of the included studies used medication adjustments and/or non-pharmacologic therapies (e.g. lifestyle interventions, improving medication adherence) as part of their telemonitoring systems.

Table 2.

Details of home blood pressure telemonitoring with automatic data transmission systems in the included studies

| Articles (year) | Devices of HBPT with automatic data transmission in the intervention group | Intervention for automatic BP monitoring system | HBP monitoring (without ABPM) in the intervention group | Usual care of BP monitoring in the control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBPT device | Devices regarding BP data transmission system | Automatic feedback (a BP report, an advice or an alert) to patients without healthcare providers’ intervention | Feedback from healthcare providers using the telemonitored BP data during study periods | Frequency | Number of daily sessions | ||

| Kario et al.17 (2021) | UA-651BLE | A smartphone app for patients, a cloud data server, and a web app console for healthcare providers | + | + | 5–7 days before study visits | 2 | Patients stored BP data in the HBP monitoring device for download at their next visit |

| Kario et al.18 (2021) | UA-651BLE | A smartphone app for patients, a cloud data server, and a web app console for healthcare providers | + | + | 5 days before study visits | 2 | Patients measured daily HBP with the HBP monitoring device and the physicians checked their written HBP data |

| Lakshminarayan et al.19 (2018) | A wireless BP monitor | A smartphone which transmitted patients’ daily BP automatically to a database | − | + | Daily | 1 | Patients measured HBP which was not transmitted and shared it with the physicians |

| Morawski et al.20 (2018) | UA-651BLE | A smartphone app | + | + | Daily | 2 | Not shown in detail (‘patients did not receive any intervention’) |

| Hoffmann-Petersen et al.30 (2017) | Omron 705IT | A telehealth monitor with GSM/GPRS communication with a central server | − | − | 3 days every second week | 2 | Patients received conventional BP monitoring |

| Kim et al.22 (2015) | UA-767PlusBT (OBP) and A&D TM-2430 (ABPM) | A smart care system | − | + | Daily | 2 | Patients were instructed to measure and record their HBP measurement in their diary and bring the data to each office visit |

| Davidson et al.31 (2015) | UA-767PlusBT | A smartphone | + | + | Every 3 days | 2 | Patients received standard care for HT |

| Kaihara et al.23 (2014) | HEM-7251G | A secure website | − | − | Daily | 2 | Patients measured HBP which was not transmitted and shared it with the physicians |

| Wakefield et al.32 (2014) | An electronic BP device | A system, a small portable, and a one-button device that transfers BP data directly | − | + | Daily | 1 (at least) | Patients were instructed to record HBP readings and bring their records to their clinic visits |

| Margolis et al.21 (2013) | UA-767PC | A secure website | − | + | 3 days per week | 2 | Patients measured their HBP in a conventional way |

| Magid et al.24 (2013) | HEM-790IT | A web app | + | + | 3 days per week | 1 | Not shown in detail |

| Rifkin et al.10 (2013) | UA-767PBT | A home health hub, which send BP data through the internet to a secure website | − | + | No specific instructions | No specific instructions | Patients were told to use their own HBP cuff as recommended by their physicians |

| McKinstry et al.11 (2013) | Stabil-O-Graph mobil | A central server | + | + | Daily (in Week 1) and at least weekly (in Weeks 2–24) | 2 | Patients were asked to continue to attend the practice for HBP checks according to the usual routine of the practice |

| Logan et al.25 (2012) | UA-767 | A custom software app running on a smartphone by which BP readings are automatically transmitted to app servers | + | − | 2 days per week | 2 | Patients were issued with an HBP device without built-in Bluetooth capability for use |

| Neumann et al.12 (2011) | Stabil-O-Graph | A mobile phone, a remote operating system, and a central database | − | + | Daily | 1 | Patients measured HBP which was not transmitted |

| Bosworth et al.26 (2011) | UA-767PC | A telemedicine device | + | + | Every other day | 1 | Patients treated with usual care received no HBP telemonitoring equipment |

| McManus et al.27 (2010) | Omron 705IT | An automatic modem device | + | + | Daily for the 1st week of each month | 1 | Patients received usual care for HT |

| Earle et al.33 (2010) | UA-767BT | A 3G mobile phone for patients and a web-based app for review by physicians | − | + | Weekly | 1 | Patients did not receive any mHealth equipment and were not required to report their HBP |

| Parati et al.28 (2009) | Tensiophone device | A referral centre where BP readings were checked and stored in a digital database | − | + | 3 days per week | 2 | Patients received an OBP-based management with the same type BP device as used for HBP monitoring |

| Madsen et al.13 (2008) | Omron 705IT | A personal digital assistant with a software interface developed for BP measurement | − | + | 3 days per week (in week 1–12) and weekly (in week 12–24) | 1 | Patients received an OBP-based management with the same type BP device as used for HBP monitoring |

| Artinian et al.14 (2007) | A BP monitor | A one-button device that transfers BP data directly | − | + | 3 days per week | 1 | Patients visited to their primary care providers whose care might have included BP measurement |

| Artinian et al.15 (2001) | UA-767PC | A one-button device that transfers BP data directly | + | + | At least 3 days per week | 1 | Patients visited to their primary care providers whose care might have included BP measurement |

| Rogers et al.29 (2001) | Model 52 500 | The Service and Support Centre | − | + | At least 3 days per week | 2 | Not shown in detail (‘patients were treated for HT according to the guidelines’) |

BP, blood pressure; app, application; HBP, home BP; HBPT, HBP telemonitoring; ABPM, ambulatory BP monitoring; GSM/GPRS, Global System for Mobile Communication/General packet radio service; OBP, office BP; mHealth, mobile health.

Table 3.

Details of the pre-specified treatment protocols specific to the intervention group in the included studies

| Articles (year) | Contents of pharmacotherapy protocols in the intervention group | Contents of non-pharmacotherapy protocols in the intervention group |

|---|---|---|

| Kario et al.17 (2021) | − | The contents of the smartphone app consisted of three key components: (i) a personalized, interactive education programme, including lectures and advice from a ‘virtual nurse’ based on biological, psychological, and social data; (ii) a lifestyle intervention based on the knowledge and techniques provided in the above educational interventions with the app support to implement lifestyle modifications; and (iii) a combination of non-pharmacological lifestyle modifications |

| Kario et al.18 (2021) | — | Patients’ baseline profiles were securely transferred to a cloud data server and analysed with a specific algorithm to generate a personalized lifestyle improvement programme to lower BP via the smartphone app |

| Lakshminarayan et al.19 (2018) | The investigators checked BP transmitted via the smartphone app and adjusted anti-hypertensive medications as needed to achieve the BP target. If patients were already taking anti-hypertensive medications, the dose of the existing medications was adjusted and new medications were added as needed. The investigators communicated with the patients by phone and email regarding medication changes | Patients were educated by a nurse coordinator on the importance of hypertension management |

| Morawski et al.20 (2018) | — | Medication lists were entered into the smartphone app. The app provided medication time alerts and generated weekly medication adherence reports. Patients could nominate a ‘Medfriend’, who had access to the patient’s medication history, received alerts when doses were missed, and provide peer support |

| Hoffmann-Petersen et al.30 (2017) | — | — |

| Kim et al.22 (2015) | Anti-hypertensive medications were adjusted and prescribed by the attending physicians according to the patients’ data. Hypertension treatments based on the major clinical guidelines were left to the discretion of the attending physicians | Patients were instructed to upload records of their daily food intake and the types and duration of their exercise programmes, which were monitored by a nutritionist and an exercise trainer |

| Davidson et al.31 (2015) | — | The MedMinder medication tray with 28 compartments provided reminder signals. At a prescribed dosing time, a light in a particular dosing compartment was flashed and activated. If the compartment was not opened, removed, and returned for 30 min, a chime activated for 30 min. If the compartment still could not be opened, an automatic reminder phone call or text message was delivered to the patient’s mobile phone |

| Kaihara et al.23 (2014) | — | — |

| Wakefield et al.32 (2014) | Advanced practice nurses in the family medicine clinic were able to modify the patients’ treatment based on currently established privileges (e.g. medication adjustments). Other nurses in the general internal medicine or family medicine clinics reviewed the data with the providers to modify the treatment plans. All treatment modifications were individualized to the patients’ needs; no standardized BP management protocols were used | — |

| Margolis et al.21 (2013) | Pharmacists emphasized lifestyle modifications and adjusted anti-hypertensive drug therapy based on an algorithm using the percentage of HBP meeting target during telephone visits. If at least 75% of readings since the last visit met the target BP, medication changes were usually not suggested. If <75% of readings met target, the algorithm recommended intensification of therapy; if patients experienced adverse effects, regardless of BP control, the dose would be reduced or the drug changed | |

| Magid et al.24 (2013) | Clinical pharmacy specialists reviewed the patients’ HBP and adherence to anti-hypertensive medications, provided counselling regarding lifestyle changes, adjusted medications as needed, and communicated with the patients by telephone or secure email. Medication changes were communicated to the primary care physicians of the patients via the electronic health record | |

| Rifkin et al.10 (2013) | Once a week, the study physicians and pharmacist met to review each patient’s BP. The patient who had consistently exceed target values in the previous week were called by either the study physicians or pharmacist to discuss the measurements, provide counselling, and adjust medications | |

| McKinstry et al.11 (2013) | Advice regarding the patients’ current BP status was provided via text message or email. These reports reassured patients that their average BP was within or below target and that they needed to contact their clinician to arrange for a change in treatment. Physicians could check the patients’ electronic general practitioner records to see if there had been any recent advice regarding medication or lifestyle changes, and if not, contact the patient to make changes | |

| Logan et al.25 (2012) | — | — |

| Neumann et al.12 (2011) | When BP alarm criteria were met, an alarm report was automatically generated and sent to physicians via email. The physicians contacted the patient by phone to resolve medication adherence issues, and changed medications if necessary | |

| Bosworth et al.26 (2011) | Nurses provided the study physicians with a medication change recommendation based on the decision support software. The study physicians reviewed the patients’ BP, medication status, and adherence with the nurses and decided whether to change hypertension medication. The nurses informed the patients of the recommended medication changes, and the study physicians prescribed the medication electronically | The behaviour management intervention consisted of 11 tailored health behaviour modules focused on improving self-management of hypertension. Patients were also provided with evidence-based recommendations for hypertension-related behaviours. Nurses used an intervention software app that included predetermined scripts and algorithms for the modules that were tailored for each patient |

| McManus et al.27 (2010) | If BP was above target for two consecutive months, patients were instructed to request a new prescription and change medications in according to the titration schedule without visiting their family physicians; if BP was above target after two changes, the patients returned to their family physicians for further implementation of the titration schedule | — |

| Earle et al.33 (2010) | Changes in treatment were based on trends in the amalgamated BP measurements and were provided by letter to patients and the general practitioner | — |

| Parati et al.28 (2009) | Treatment was titrated to decrease self-measured HBP and was combined with teletransmission. To achieve the treatment BP goals, physicians were allowed to prescribe any anti-hypertensive or combination of drugs they deemed clinically appropriate | — |

| Madsen et al.13 (2008) | General practitioners were instructed to check the website weekly to monitor BP of the patients, and implement or modify anti-hypertensive treatment at their own discretion with the goal of achieving each patient’s target HBP | — |

| Artinian et al.14 (2007) | — | Telecounselling with intervention nurses on lifestyle modification and medication adherence helped patients learn and incorporate hypertension self-care behaviours into their daily routine or establish them as a habit |

| Artinian et al.15 (2001) | — | Patients were provided with telephone counselling by specially trained registered nurses on content related to adherence to their anti-hypertension medications and lifestyle modification |

| Rogers et al.29 (2001) | A computerized report of the BP results was faxed to each patient’s physician. Upon receiving a report form indicating elevated BP, the physicians adjusted the anti-hypertensive medications by telephone, an office visit, or both | — |

BP, blood pressure; app, application; HBP, home BP.

Reasons for dropout

The duration of the study ranged from 4 to 72 weeks, with an average duration of 27 weeks (1 month was considered as 4 weeks). The average completion rate for the included studies was 89.5% (range 69.3%33 to 98.3%23). Causes of dropout included lack of interest or motivation,11,23,27 medical reasons,11–13,15,17,19,21,25,26,29,31 changes in personal circumstances,12,15,17,26,31 technical problems with device equipment or application,10,13,27 and unwillingness to disclose personal information.31 The dropout rate for the studies included in this review was <20% in 19 of 23 studies, which can be considered acceptable.34

Study quality

The risk of bias was assessed in each study. No study showed a high risk of bias for allocation concealment. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and personnel was not possible. Detection bias was considered low in all 23 studies because the SBP/DBP as the outcome was measured by an instrument with automatic data transmission and patients simply pressed a button without bias. Overall, all studies were considered to be of high quality (see Supplementary material online, S4). Since the funnel plots of the main outcomes (see Supplementary material online, S5) were nearly symmetrical, no evidence of strong publication bias was found.

Outcomes

A total of 19 studies reported SBP/DBP as the outcome. Eleven studies and 10 studies on OBP reported SBP and DBP as the outcome. Figure 2 shows the results of a meta-analysis and forest plots performed between the two groups. Systolic blood pressure was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group [mean difference −6.0 mmHg; 95% CI (−8.9 to −3.1 mmHg); P < 0.001], but there was considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 79%, P < 0.001). Diastolic blood pressure was also significantly lower in the intervention group. Five papers and four papers on HBP reported SBP and DBP as the outcome. Systolic blood pressure was significantly decreased in the intervention group compared with the control group [mean difference −4.4 mmHg; 95% CI (−7.1 to −1.8 mm Hg); P = 0.001] with considerable heterogeneity found (I2 = 66%, P = 0.02). Diastolic blood pressure was not significantly decreased in the intervention group compared with the control group (see Supplementary material online, S6). Ten papers for ABPM reported SBP and DBP as the outcome. Systolic blood pressure was significantly decreased in the intervention group compared with the control group [mean difference −2.4 mmHg; 95% CI (−3.9 to −0.9 mmHg); P = 0.002] with considerable heterogeneity found (I2 = 60%, P = 0.008). Diastolic blood pressure was also significantly decreased in the intervention group (see Supplementary material online, S7).

Figure 2.

Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring with automatic data transmission on blood pressure reduction in office blood pressure. SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse-variance; CI, confidence interval.

Subgroup analyses

Smartphone application usage

Eligible studies measured by OBP were divided into those with and without a smartphone application; SBP was reported as the outcome in three studies with a smartphone application and eight studies without. Figure 3 reports a significant decrease in SBP in the intervention group compared with the control group [mean difference −3.7 mmHg; 95% CI (−6.2 to −1.2 mm Hg); P = 0.004] with low heterogeneity found (I2 = 0%, P = 0.99) using a smartphone application. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify the impact of eliminating studies, but it was not significant for studies that did not use the smartphone application. No significant difference was shown between these subgroups (P = 0.17). If the studies with HBP as an outcome are also included in Figure 3 using standardized mean difference, Figure 4 also reports a significant decrease in SBP in the intervention group compared with the control group [standardized mean difference −0.25; 95% CI (−0.44 to −0.05); P = 0.01] with substantial heterogeneity found (I2 = 52%, P = 0.08). Diastolic blood pressure showed a significant reduction as SBP. Although excluded from the meta-analysis, Davidson et al.31 also showed that the smartphone programme significantly lowered resting office SBP and DBP than the standard care.

Figure 3.

Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring with automatic data transmission on blood pressure reduction in office blood pressure, divided by whether or not a smartphone application was used. app, application; SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse-variance; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring with automatic data transmission on blood pressure reduction in office and home blood pressure, divided by whether or not a smartphone application was used. app, application; SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse-variance; CI, confidence interval.

Observational duration

The included studies measured by OBP were divided into two categories: those with observation periods of more than or equal to 48 weeks and those of <48 weeks. Three studies in the first category and eight studies in the second category reported SBP as the outcome. The average dropout rate for the studies of 48 weeks or more was 88.7%; for the studies of <48 weeks, it was 90.6%. Supplementary material online, S8 reported a significant reduction in SBP in the intervention group compared with the control group [mean difference −6.3 mmHg; 95% CI (−9.6 to −3.0 mmHg); P < 0.001] with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 60%, P = 0.08) in studies of more than or equal to 48 weeks. A sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the impact of excluding trials, but it was not significant for trials of <48 weeks. There were no significant differences between these subgroups (P = 0.94).

Multidisciplinary approaches

The targeted studies measured by OBP were divided into three categories of interventions: involving physicians only, physicians and nurses, and physicians and pharmacists. Office SBP was reported as the outcome in the three studies with only physicians, four with physicians and nurses, and three with physicians and pharmacists. Supplementary material online, S9 shows that SBP was significantly or tended to be lower in the intervention group compared with the control group in the studies with these three groups. Significant subgroup difference was shown (P = 0.02), and post hoc analysis showed that the studies of physicians and pharmacists had a significantly better impact on BP reduction than the studies of physicians only (P = 0.006). Additional subgroup analysis was performed to detect differences among these studies with office SBP as the outcome, using both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (five studies) and one of these interventions (six studies). Supplementary material online, S10 reports that using both interventions resulted in significantly lower SBP in the intervention group compared with the control group [mean difference −7.2 mmHg; 95% CI (−11.6 to −2.8 mmHg); P = 0.001] with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 75%, P = 0.003). One intervention measure also showed a significant office SBP reduction [mean difference −4.8 mmHg; 95% CI (−8.2 to −1.4 mmHg); P = 0.005] with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 73%, P = 0.002). There were no significant differences between these subgroups (P = 0.39).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using modern information technology tools with automatic HBP transmission shows a significant improvement of BP treatment when compared with the classical way of following up hypertensive patients. The results are summarized in the following key findings. (i) Home blood pressure telemonitoring with an automatic data transmission system has a beneficial impact on BP reduction compared with usual care. (ii) Smartphone application use has a positive impact on BP improvements. (iii) The system remains effective even for monitoring durations of 48 weeks or above and dropout rates were low even for long-term follow-up.

The analysis shows that HBPT with automatic data transmission reduces SBP/DBP by 6/2 mmHg more than with the classical HBP management method. The latest meta-analysis has demonstrated that lowering SBP by 5 mmHg reduces the risk of major cardiovascular events by ∼10%.35 This result means that this system will improve cardiovascular prognosis. A previous review36 has shown that medication adherence during the first year of hypertension management is usually <50%. Although special populations may be included in the RCTs, it is possible to maintain high adherence using this system. Patients’ simple use of such HBPT with an automatic data transmission system and subjective participation in clinical practice can lead to good outcomes.

There is no systematic review that mentions the effect of HBPT using a smartphone application. Smartphone applications include multidisciplinary contents such as personalized lifestyle modification, patient education,18,19 medication reminders,20 and automatic prompt feedback systems18,19,25 other than HBPT. In addition, the results of a recent trial of digital therapeutics (a subset of digital health tools that provide evidence-based therapeutic interventions37) by Kario et al.17,18 have reported a significant reduction in BP, which is promising. In the past, alerts and simple messages were the main application features of feedback, but now the application itself is very comprehensive and allows for more personalized and patient-specific interventions based on the many data entered into the application. On the other hand, one hurdle is that the use of smartphone applications may be low, especially among old patients. In general, old age and digital literacy are the main barriers to digital cardiology,38 and the use of smartphone applications is not exceptional. The recent paper shows that digital literacy, not age itself, is independently associated with interest in mobile health (mHealth).39 However, even with such weaknesses, several studies31,33 indicate that the use of smartphone applications has a beneficial impact.

The review, which focuses exclusively on telemonitoring systems that automatically transmit BP data, has found significant BP reductions in studies with long-term follow-up. It is consistent with other systematic reviews.40,41 The results of this review not only confirm them but by focusing on modern automatic transmission expand the knowledge base that may lead to an easier implementation. However, there is not enough evidence on the lifelong effects of digital health.42 For long-lasting effects, digital technology needs the patients’ active participation and adherence to treatment. A previous systematic review43 reported that mHealth may increase patient adherence to chronic disease management. The results reflect that the usability of digital devices enhances adherence, even considering the low dropout rate as mentioned above. More evidence is needed, especially for smartphone applications.

Previous systematic reviews40,41 have shown the BP-reducing effects of HBPT, the long-term effects, and the effects of HBPT with collaborative intervention by multidisciplinary teams. As mentioned above, only papers with automatic transmission of BP data were selected for the systematic review. Data transfer by phone, mail, or healthcare provider visits is not included. This does not mean that only digital devices are important and that multidisciplinary cooperation is not necessary. However, recent smartphone applications can include a virtual nurse or pharmacist. Several studies employed automatic feedback to the patient without the intervention of a healthcare provider in the telemonitoring system (Table 2), and all of the studies with smartphone applications18–20,25,31 incorporated it. This type of HBPT with an automatic data transmission system has been shown to be excellent independent of the caregiver group. The effectiveness of combined pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacotherapy interventions (Supplementary material online, S10) supports the importance of healthcare professionals other than physicians and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach as one team around the patient. An important next step will be to figure out in which situations (e.g. hospitals and clinics) this new technology can be most effectively implemented.

Future developments

In the era of digital health, we need to apply the latest HBPT with automatic data transmission results to our patients. Comprehensive smartphone and web applications that support patient self-control will be applied. They should include decision support systems, and data sharing systems for patients, their families, and healthcare professionals. There is an urgent need for adopting homogenous protocol for BP data transmission and analysis among different devices and manufacturers in order to provide more uniform and comparable data across different hypertension centres and nations. These will lead to personalized medicine in the future of digital cardiology. We must continue to improve the system for the sake of the patients who are less digitally literate.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. First, only articles in English were included, and no attempt was made to include grey literature. Second, some studies used inputted data, and four studies mentioned above were excluded from the meta-analysis because the mean and/or the SD values for effect sizes were not available in the literature. Third, even with subgroup analysis, the heterogeneity of the studies remained. The review focuses only on HBPT with automatic data transmission systems using digital devices and selects a random-effects model, but there are many different types of devices, programmes, and ways to work with healthcare providers. Finally, the issue of workload in analysing telemonitored data has yet to be solved. In the 2021 review,38 the top reason cited for physician-level barriers was ‘increased work and responsibilities’. Unfortunately, the included papers were not able to calculate the workload of healthcare workers. However, automatic feedback from an application is part of the solution because it can eliminate the time required to analyse telemonitoring data and repetitive alerts by medical personnel.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis shows that HBPT with automatic data transmission systems is more effective in lowering blood pressure than usual care. In particular, smartphone application use significantly reduces blood pressure. The results support the routine use of digital cardiology using automatic transmission of data in the field of hypertension management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the staff members of the laboratories and the statistician at the Jessa Hospital for their effort and understanding in this review.

Contributor Information

Toshiki Kaihara, Department of Cardiology, Heart Centre Hasselt, Jessa Hospital, Stadsomvaart 11, 3500 Hasselt, Belgium; Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences/Human-Computer Interaction and eHealth, UHasselt, Agoralaan gebouw D, 3590 Diepenbeek, Belgium; Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, 2-16-1 Sugao, 216-8511 Kawasaki, Japan.

Valent Intan-Goey, Antwerp University Hospital, Drie Eikenstraat 655, 2650 Edegem, Belgium.

Martijn Scherrenberg, Department of Cardiology, Heart Centre Hasselt, Jessa Hospital, Stadsomvaart 11, 3500 Hasselt, Belgium; Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences/Human-Computer Interaction and eHealth, UHasselt, Agoralaan gebouw D, 3590 Diepenbeek, Belgium; Faculty of Medicine, University of Antwerp, Prinsstraat 13, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium.

Maarten Falter, Department of Cardiology, Heart Centre Hasselt, Jessa Hospital, Stadsomvaart 11, 3500 Hasselt, Belgium; Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences/Human-Computer Interaction and eHealth, UHasselt, Agoralaan gebouw D, 3590 Diepenbeek, Belgium; Faculty of Medicine, KULeuven, Oude Markt 13, 3000 Leuven, Belgium.

Kazuomi Kario, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Jichi Medical University School of Medicine, 3311-1 Yakushiji, 329-0498 Shimotsuke, Japan.

Yoshihiro Akashi, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, 2-16-1 Sugao, 216-8511 Kawasaki, Japan.

Paul Dendale, Department of Cardiology, Heart Centre Hasselt, Jessa Hospital, Stadsomvaart 11, 3500 Hasselt, Belgium; Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences/Human-Computer Interaction and eHealth, UHasselt, Agoralaan gebouw D, 3590 Diepenbeek, Belgium.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Digital Health.

Data availability

All dataset analysed are included in this manuscript and supplementary materials.

References

- 1. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Rosei EA, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerin M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais I; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021–3104.30165516 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Kato J, Kikuchi N, Nishiyama A, Aihara A, Sekino M, Kikuya M, Ito S, Satoh H, Hisamichi S. Home blood pressure measurement has a stronger predictive power for mortality than does screening blood pressure measurement: a population-based observation in Ohasama, Japan. J Hypertens 1998;16:971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scherrenberg M, Wilhelm M, Hansen D, Völler H, Cornelissen V, Frederix I, Kemps H, Dendale P. The future is now: a call for action for cardiac telerehabilitation in the COVID-19 pandemic from the secondary prevention and rehabilitation section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021;28:524–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mengden T, Hernandez Medina RM, Beltran B, Alvarez E, Kraft K, Vetter H. Reliability of reporting self-measured blood pressure values by hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens 1998;11:1413–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Noda A, Obara T, Abe S, Yoshimachi S, Satoh M, Ishikuro M, Hara A, Metoki H, Mano N, Ohkubo T, Goto T, Imai Y. The present situation of home blood pressure measurement among outpatients in Japan. Clin Exp Hypertens 2020;42:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Omboni S, Panzeri E, Campolo L. E-Health in hypertension management: an insight into the current and future role of blood pressure telemonitoring. Curr Hypertens Rep 2020;22:42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Page MJ, Moher D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and extensions: a scoping review. Syst Rev 2017;6:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0.

- 9. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks TJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rifkin DE, Abdelmalek JA, Miracle CM, Low C, Barsotti R, Rios P, Stepnowsky C, Agha Z. Linking clinic and home: a randomized, controlled clinical effectiveness trial of real-time, wireless blood pressure monitoring for older patients with kidney disease and hypertension. Blood Press Monit 2013;18:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McKinstry B, Hanley J, Wild S, Pagliari C, Paterson M, Lewis S, Sheikh A, Krishan A, Stoddart A, Padfield P. Telemonitoring based service redesign for the management of uncontrolled hypertension: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;346:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Neumann CL, Menne J, Rieken EM, Fischer N, Weber MH, Haller H, Schulz EG. Blood pressure telemonitoring is useful to achieve blood pressure control in inadequately treated patients with arterial hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 2011;25:732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Madsen LB, Kirkegaard P, Pedersen EB. Blood pressure control during telemonitoring of home blood pressure. A randomized controlled trial during 6 months. Blood Press 2008;17:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Artinian NT, Flack JM, Nordstrom CK, Hockman EM, Washington OGM, Jen KLC, Fathy M. Effects of nurse-managed telemonitoring on blood pressure at 12-month follow-up among Urban African Americans. Nurs Res 2007;56:312–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Artinian NT, Washington OGM, Templin TN. Effects of home telemonitoring and community-based monitoring on blood pressure control in urban African Americans: a pilot study. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care 2001;30:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kario K, Nomura A, Harada N, Okura A, Nakagawa K, Tanigawa T, Hida E. Efficacy of a digital therapeutics system in the management of essential hypertension: the HERB-DH1 pivotal trial. Eur Heart J 2021;42:4111–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kario K, Nomura A, Kato A, Harada N, Tanigawa T, So R, Suzuki S, Hida E, Satake K. Digital therapeutics for essential hypertension using a smartphone application: a randomized, open-label, multicenter pilot study. J Clin Hypertens 2021;23:923–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lakshminarayan K, Westberg S, Northuis C, Fuller CC, Ikramuddin F, Ezzeddine M, Scherber J, Speedie S. A mHealth-based care model for improving hypertension control in stroke survivors: pilot RCT. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;70:24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morawski K, Ghazinouri R, Krumme A, Lauffenburger JC, Lu Z, Durfee E, Oley L, Lee J, Mohta N, Haff N, Juusola JL, Choudhry NK. Association of a smartphone application with medication adherence and blood pressure control: the MedISAFE-BP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:802–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Margolis KL, Asche SE, Bergdall AR, Dehmer SP, Groen SE, Kadrmas HM, Kerby TJ, Klotzle KJ, Maciosek MV, Michels RD, O’Connor PJ, Pritchard RA, Sekenski JL, Sperl-Hillen JAM, Trower NK. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure control a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim YN, Shin DG, Park S, Lee CH. Randomized clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of remote patient monitoring and physician care in reducing office blood pressure. Hypertens Res 2015;38:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaihara T, Eguchi K, Kario K. Home BP monitoring using a telemonitoring system is effective for controlling BP in a Remote Island in Japan. J Clin Hypertens 2014;16:814–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Magid DJ, Olson KL, Billups SJ, Wagner NM, Lyons EE, Kroner BA. A pharmacist-led, American Heart Association Heart360 web-enabled home blood pressure monitoring program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Logan AG, Jane Irvine M, McIsaac WJ, Tisler A, Rossos PG, Easty A, Feig DS, Cafazzo JA. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring with self-care support on uncontrolled systolic hypertension in diabetics. Hypertension 2012;60:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, McCant F, Grubber J, Smith V, Gentry PW, Rose C, Van Houtven C, Wang V, Goldstein MK, Oddone EZ. Home blood pressure management and improved blood pressure control: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McManus RJ, Mant J, Bray EP, Holder R, Jones MI, Greenfield S, Kaambwa B, Banting M, Bryan S, Little P, Williams B, Richard Hobbs FD. Telemonitoring and self-management in the control of hypertension (TASMINH2): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parati G, Omboni S, Albini F, Piantoni L, Giuliano A, Revera M, Illyes M, Mancia G. Home blood pressure telemonitoring improves hypertension control in general practice. The TeleBPCare study. J Hypertens 2009;27:198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rogers MAM, Small D, Buchan DA, Butch CA, Stewart CM, Krenzer BE, Husovsky HL. Home monitoring service improves mean arterial pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoffmann-Petersen N, Lauritzen T, Bech JN, Pedersen EB. Short-term telemedical home blood pressure monitoring does not improve blood pressure in uncomplicated hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens 2017;31:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davidson TM, McGillicuddy J, Mueller M, Brunner-Jackson B, Favella A, Anderson A, Torres M, Ruggiero KJ, Treiber FA. Evaluation of an mHealth medication regimen self-management program for African American and Hispanic uncontrolled hypertensives. J Pers Med 2015;5:389–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wakefield BJ, Koopman RJ, Keplinger LE, Bomar M, Bernt B, Johanning JL, Kruse RL, Davis JW, Wakefield DS, Mehr DR. Effect of home telemonitoring on glycemic and blood pressure control in primary care clinic patients with diabetes. Telemed e-Health 2014;20:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Earle KA, Istepanian RSH, Zitouni K, Sungoor A, Tang B. Mobile telemonitoring for achieving tighter targets of blood pressure control in patients with complicated diabetes: a pilot study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010;12:575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, Maher CG, Deyo RA, Schoene M, Bronfort G, Van Tulder MW. 2015 Updated method guideline for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back and Neck Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:1660–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. The Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration . Pharmacological blood pressure lowering for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease across different levels of blood pressure: an individual participant-level data meta-analysis. Lancet 2021;397:1625–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hill M, Miller N, Degeest S, American Society of Hypertension Writing Group . ASH position paper: adherence and persistence with taking medication to control high blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens 2010;12:757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Digital Therapeutics Alliance . Transforming Global Healthcare by Advancing Digital Therapeutics. https://dtxalliance.org (9 December 2021).

- 38. Whitelaw S, Pellegrini DM, Mamas MA, Cowie M, Van Spall HGC. Barriers and facilitators of the uptake of digital health technology in cardiovascular care: a systematic scoping review. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2021;2:62–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thimo M, Christian B, Tabea G, Judith P, Prisca E, Matthias W. Patient interest in mHealth as part of cardiac rehabilitation in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2021;151:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Duan Y, Xie Z, Dong F, Wu Z, Lin Z, Sun N, Xu J. Effectiveness of home blood pressure telemonitoring: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J Hum Hypertens 2017;31:427–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tucker KL, Sheppard JP, Stevens R, Bosworth HB, Bove A, Bray EP, Earle K, George J, Godwin M, Green BB, Hebert P, Hobbs FDR, Kantola I, Kerry SM, Leiva A, Magid DJ, Mant J, Margolis KL, Mckinstry B, Mclaughlin MA, Omboni S, Ogedegbe O, Parati G, Qamar N, Tabaei BP, Varis J, Verberk WJ, Wakefield BJ, Mcmanus RJ. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jandoo T. WHO guidance for digital health: what it means for researchers. Digit Heal 2020;6:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, Green BB, Ginsburg AS. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All dataset analysed are included in this manuscript and supplementary materials.