Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic presented new barriers and exacerbated existing inequities for physician scholars. While COVID-19’s impact on academic productivity among women has received attention, the pandemic may have posed additional challenges for scholars from a wider range of equity-deserving groups, including those who hold multiple equity-deserving identities. To examine this concern, the authors conducted a scoping review of the literature through an intersectionality lens.

Method

The authors searched peer-reviewed literature published March 1, 2020, to December 16, 2021, in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, and PubMed. The authors excluded studies not written in English and/or outside of academic medicine. From included studies, they extracted data regarding descriptions of how COVID-19 impacted academic productivity of equity-deserving physician scholars, analyses on the pandemic’s reported impact on productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups, and strategies provided to reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups.

Results

Of 11,587 unique articles, 44 met inclusion criteria, including 15 nonempirical studies and 29 empirical studies (22 bibliometrics studies, 6 surveys, and 1 qualitative study). All included articles focused on the gendered impact of the pandemic on academic productivity. The majority of their recommendations focused on how to alleviate the burden of the pandemic on women, particularly those in the early stages of their career and/or with children, without consideration of scholars who hold multiple and intersecting identities from a wider range of equity-deserving groups.

Conclusions

Findings indicate a lack of published literature on the pandemic’s impact on physician scholars from equity-deserving groups, including a lack of consideration of physician scholars who experience multiple forms of discrimination. Well-intentioned measures by academic institutions to reduce the impact on scholars may inadvertently risk reproducing and sustaining inequities that equity-deserving scholars faced during the pandemic.

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, early commentaries highlighted its gendered impact on academic productivity. 1–3 Initial analyses of papers available in preprint servers suggested that the authorship gender gap had widened, with men publishing at an increased rate relative to women. 4 This gender differential was reportedly more apparent for research related to COVID-19 5 and in analyses comparing first and last authorship. 6 The findings prompted discussion regarding the impact of the pandemic on the academic productivity of women, particularly mothers, 7–9 and what the academic community should do to respond. 10

It is unsurprising that the disruptions caused by the pandemic may have widened a preexisting and persistent gender gap in academia. Before the pandemic, maternity leave, childbearing, and domestic responsibilities, combined with unconscious bias and the “publish or perish” principle, had a well-documented differential impact on the career progression of women in academia. 11–17 However, the emphasis on women and mothers in the wider literature unintentionally overshadowed the impact on a broader range of equity-deserving groups, including those who hold multiple, intersecting equity-deserving identities and who, as a result, may experience multiple, intersecting oppressions. The term “intersectionality” was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to understand the interconnected nature of social and political identities and how these overlapping identities create systems of discrimination 18; this concept describes how individuals can be disadvantaged by multiple sources of oppression, including their race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and other identity markers. Understanding how these overlapping identities intersect is important for addressing issues of discrimination and prejudice. For example, we know little about how the division of household labor among Black women or transgender people affects academic advancement. 19–21

Although the pandemic exacerbated existing inequities in academia in general, the additional responsibility of providing clinical care sets academic medicine apart from other disciplines. Before the pandemic, the culture of academic medicine required physicians who engaged in research to not only meet clinical care demands but also pursue scholarly activities which often occur outside of work hours. Barriers to work–life integration are therefore deeply rooted within academic medicine. 22 Physician scholars working at academic institutions already faced high expectations for research productivity (i.e., grants, publications). 23 So during the pandemic, the expanded expectations for clinical care and academic productivity combined with the increased demands of home life were especially challenging. 24,25 For example, scholars have described how pandemic created a “she-cession” whereby women moved toward “down-shifting” their careers or leaving the workplace altogether more often than men. 26,27

We conducted a scoping review to document the peer-reviewed literature on the academic productivity of physicians from equity-deserving groups during the pandemic. Its purpose was to see if there were published articles on the pandemic’s impact on academic productivity that moved beyond a gendered analysis. We wanted to uncover the extent to which the literature on academic productivity explored intersectional disparities to understand the burden of the pandemic on equity-deserving physician scholars. Since research on the gendered impact of disease outbreaks remains generally scarce, 28 we anticipated a paucity of research addressing the intersecting impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic productivity that would underscore unprecedented adjustments to work–life integration. 29

Method

We employed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework 30 to conduct the scoping study. Scoping studies are useful for examining emerging evidence and when it is still unclear what other questions might be posed and addressed by other more precise knowledge syntheses, like systematic reviews. 31 We used 3 of the 4 reasons cited for conducting a scoping review 30: to examine the extent, range, and nature of a research activity in a given area; to summarize and disseminate research findings; and to identify gaps in the existing body of literature. The fourth reason (i.e., to determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review) was not considered, as our intent was not to examine interventions.

We divided the article selection process for our review into 5 stages.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

Our scoping review was guided by the research question: What is known in the literature about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the academic productivity of physicians from equity-deserving groups? The objectives of this research were to: (1) document the factors that describe or explain the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic productivity, (2) report the pandemic’s impact on academic productivity, and (3) synthesize the strategies and recommendations provided in these studies to reduce the impact of the pandemic on academic productivity.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

A research librarian (S.C.) and 3 additional coauthors (S.S., G.B., A.K.) developed comprehensive search strategies. Three electronic databases were searched: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, and PubMed. The latter database was included to capture newly published COVID-19 articles that had not yet been indexed in Ovid MEDLINE.

A comprehensive search strategy was first developed in Ovid MEDLINE. Subject headings and keywords were searched for the individual concepts of COVID-19, scholarly output, and “minority” groups, and then combined with AND. A date limit for 2020–current was applied. We chose 2020 (March 1, 2020, in PubMed) to align with when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. 32 No language restriction was applied in the searches. No gray literature was searched. The search strategy was peer-reviewed by another experienced librarian and refined with the research team before initiating the full search. See Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B338 for full search strategies. The initial search was completed on June 25, 2021, with search updates conducted on September 20, 2021, and December 16, 2021. Search results were uploaded to the Covidence (v2.0) systematic review management software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia), where we conducted the subsequent screening and extraction phases.

Stage 3: Study selection

We included articles published in peer-reviewed journals between March 1, 2020, and December 16, 2021. Two coauthors (S.S., G.B.) and other research staff independently reviewed all citations and full-text articles for inclusion, with disagreements resolved through discussion among all coauthors. To be included, articles needed be written in English and had to discuss the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic productivity among physician scholars who are members of equity-deserving groups. We defined “academic productivity” as activities associated with producing published research outputs (e.g., publishing peer-reviewed papers, applying for research funding/grants). We excluded papers that focused on the impact of COVID-19 on physician scholars’ activities more broadly (e.g., tenure, mentoring, service development, teaching or thesis supervision). The focus on physicians meant that we excluded literature that focused on trainee scholars (e.g., medical students, master’s degree or PhD students, residents). To help us decide whether articles met the “physician scholar” criteria, we used the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada’s list of accredited disciplines, 33 the Association of American Medical College’s Speciality Profiles, 34 and the CanMEDS-Family Medicine competency framework. 35 As a result, we excluded articles that focused on “nonphysician” disciplines such as dentistry and pharmacy. Finally, all qualifying articles had to discuss physician scholars from equity-deserving groups as opposed to physician scholars in general. We use the term “equity-deserving groups” to build on advancements made by historically and systemically marginalized groups and to acknowledge that ongoing historical and systemic barriers to opportunities and equal access disproportionately affect some people more than others. 36 We recognize that language is constantly evolving and that inclusive terminology is sensitive to time period and geographic locations. Our intent for using this term is based on respect and minimizing harm. 37 See Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B338 for full inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Stage 4: Charting the data

The coauthors developed a single data extraction sheet that expanded on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Review checklist (PRISMA-ScR). 38 See Supplemental Digital Appendix 3 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B338 for the data extraction sheet. Two coauthors and members of research staff completed data extraction for each included article. As a data extraction accuracy check, a member of the research staff completed a second review and extraction for 13 of the 44 included articles (interrater agreement = 86%). The coauthors analyzed and discussed any areas of discrepancy and completed a final quality check of the full dataset based on these discussions.

Stage 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

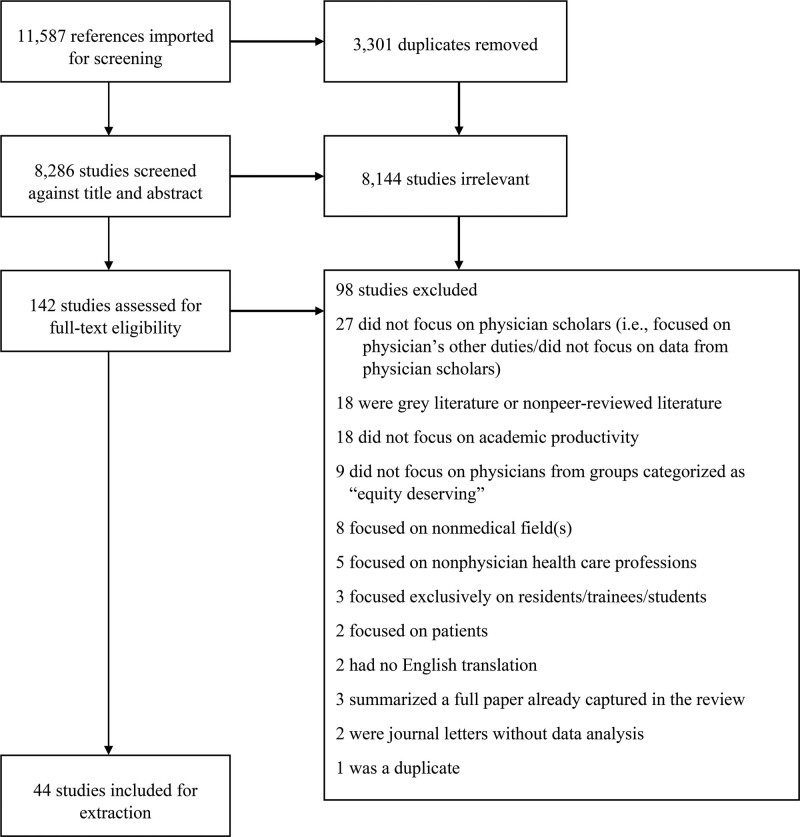

Our initial search yielded 11,587 results. After the removal of 3,301 duplicates, we screened the remaining 8,286 papers, advancing 142 to full-text review. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 44 of the 142 articles were selected for extraction 26,39–81 Figure 1 provides a diagram outlining the PRISMA results flowchart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR 38 flow diagram outlining review process and results for a scoping review of articles published from March 1, 2020, to December 16, 2021, on the impact of COVID-19 on academic productivity among physician scholars from equity-deserving groups.

One author (S.S.) reviewed the reference lists of the 44 articles to ensure that there were no additional references relevant to our search, and none were identified. An inductive approach was used to organize and analyze the extracted data, which were then reviewed and discussed by all authors using a constant comparison method. All commonalities and differences were discussed by 2 coauthors (S.S., G.B.) until a core set of categories were developed.

Results

Summary

As anticipated, the 44 articles that met our inclusion criteria primarily focused on women, and in particular mothers. The articles included limited discussion regarding physician scholars from equity-deserving groups other than women, and discussions regarding women who experience multiple intersecting inequities was also limited. We extracted descriptive statistics from the papers, as well as information related to the following themes: descriptions of how COVID-19 impacted academic productivity of equity-deserving physician scholars, analyses on the pandemic’s reported impact on productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups, and strategies provided to reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups.

Descriptive statistics

Of the 44 articles selected for extraction, 22 (50%) focused on academic medicine in general rather than on a specific medical area 26,39,43,44,46,50,52–54,56–60,63,68,70,71,75,78–80; the remaining publications focused on cardiology (n = 4, 9%), 42,69,72,74 radiology (n = 4, 9%), 61,64,66,73 emergency medicine (n = 2, 5%), 41,55 hematology or transfusion medicine (2, 5%), 40,47 ophthalmology (n = 2, 5%), 48,62 oncology (n = 2, 5%), 45,49 psychiatry (n = 1, 3%), 67 obstetrics and gynecology (n = 1, 3%), 81 osteopathic medicine (n = 1, 3%), 77 pediatrics (n = 1, 3%), 76 surgery (n = 1, 3%), 51 and urology (n = 1, 3%). 65 Articles were divided into 2 broad categories: nonempirical articles that did not collect or analyze primary or secondary data (n = 15, 34%) 26,48–50,54,59,60,68–70,72,73,77,79,80 and empirical articles that collected and/or analyzed data (n = 29; 66%). 39–47,51–53,55–58,61–67,71,74–76,78,81

Descriptions of how COVID-19 impacted academic productivity of equity-deserving physician scholars

The included articles described the negative impact of the pandemic as an “amplification,” 41,57,59 “exacerbation,” 44,47,54,61,62,64 and “aggravation” 68,73 of preexisting inequalities related to the division of domestic and childcare responsibilities between women and men. These 11 articles pointed to the increased burden of domestic and childcare duties shouldered by women and the negative influence on their academic productivity. 45,46,48,51,52,57–59,62,64,68–71 For example, the task of organizing childcare (emergency or otherwise) usually falls to mothers more than fathers, and the ability to “outsource” these activities during the pandemic was no longer available. 64,73 The pandemic and the ramifications of school and childcare closures had the potential to magnify these preexisting gender differences in home and childcare, negatively impacting academic productivity. Ten of the 11 articles specifically focused on the pressures for early-career women physicians, including the stress of caring for children and/or elderly or sick relatives during the pandemic. 42,46,48,56,64,65,68,70,71,74 Overall, the discussion of domestic responsibilities and household labor division centered on cisgender women and men.

Five of the included articles described the working environment of academic medicine as being overtly hostile to women. 54,56,63,66,67 One article described how some men tend to minimize women’s professional qualifications and how women remain invisible as experts (i.e., the use of “stale, pale manels” at scientific conferences) 82 noting how this aggressive environment may have worsened during the pandemic, as denoted by derogatory or sexist comments that some individuals voiced about women as medical professionals. 54 Other articles explained how women may be overtly or covertly denied access to COVID-19 research because the research agenda is mainly shaped by those in leadership positions, most of whom are men. 56,63,66 Also, some articles highlighted that women may be more likely than men to agree to perform additional service-related or other unpromotable tasks, further reducing their time to engage in publishing and grant writing. 46,67,71,74 One article described how, by increasing school and childcare responsibilities, COVID-19 increased rates of compassion fatigue, burnout, workplace sexual harassment, and imposter syndrome for women physicians, while also limiting opportunities for advancement. 59

Analyses on the pandemic’s impact on productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups

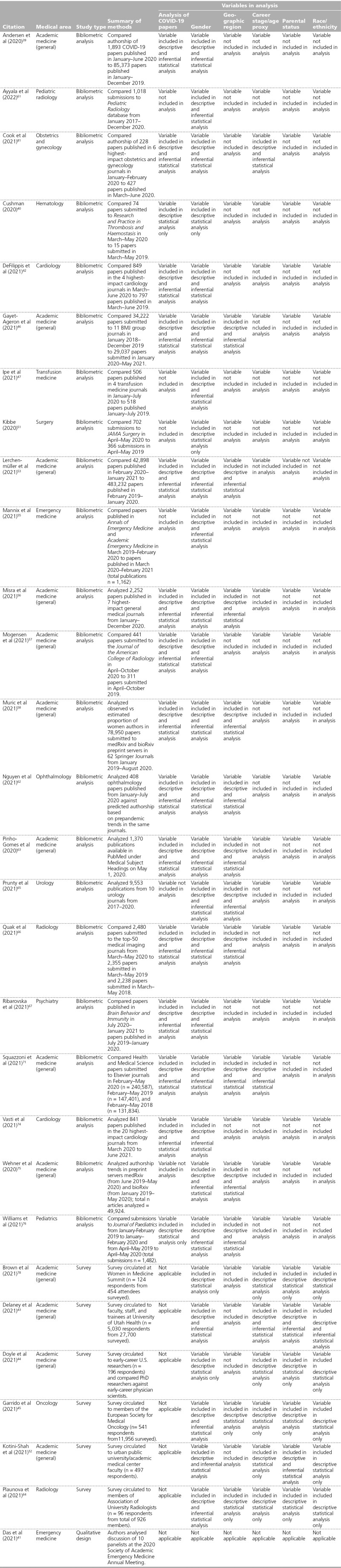

Several articles moved beyond positing that the pandemic had a negative impact on women’s academic productivity to explore this phenomenon through empirical analyses. In all, 29 of the 44 included articles (66%) were empirical publications, and of these, 22 included bibliometric analyses, 39,40,42,46,47,51,53,55–58,61–63,65–67,71,74–76,81 6 included survey designs, 43–45,52,64,78 and 1 included a qualitative study. 41 Table 1 provides an overview of the key characteristics for these 29 empirical papers.

Table 1.

Key Characteristics of 29 Empirical Papers Included in a Scoping Review Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on the Academic Productivity of Physician Scholars From Equity-Deserving Groups

Bibliometric analyses.

All 22 bibliometric publications primarily focused on the gendered impact of the pandemic on authorship rates in medical journals. Broadly, bibliometric analyses explored the proportion of women in the first author, last author, or corresponding author position for papers submitted or published before the pandemic compared with after the start of the pandemic, either overall (e.g., on all topics) or, more specifically, for papers related to COVID-19. The time periods analyzed after the emergence of the pandemic ranged from the first few months of 2020 to mid-2021. Given the time it takes to produce and submit research outputs, the full impact of the pandemic on published work will likely not become apparent until a later date. However, a number of the bibliometric studies looked at data outputs that may have shown up at an earlier stage of the pandemic (e.g., submissions, preprints, analyses that focused on COVID-19 research specifically). For example, while 12 of the 22 bibliometric studies analyzed publications, 39,42,47,53,55,56,62,63,65,67,74,81 8 analyzed submissions 40,46,51,57,61,66,71,76 and 2 analyzed preprints. 58,75 Nevertheless, given the time periods analyzed, caution is advised when interpreting these findings.

In the 14 papers that included an analysis of women’s authorship overall (i.e., not specific to COVID-19 related papers), evidence that the pandemic had a differential impact on women’s ability to submit and publish in peer-reviewed journals was mixed. Four of these papers indicated that that the proportion of women’s overall authorship in medical journals had decreased when compared with prepandemic levels. 51,58,71,75 Seven papers found no significant difference in the proportion of women’s overall authorship 40,55,57,65,66,76,81; 2 papers reported mixed results (1 finding a significant decrease in women first authors from January 1 to July 31, 2020, when compared with the previous year 47; and 1 finding a significant decrease in women last authors from April to June 2020 compared with the previous year). 61 One paper reported an increase in the proportion of both women first and last authors after the onset of the pandemic. 42

Despite the variability of results related to overall authorship, subgroup analysis pointed to differential areas of impact for women. Of the 16 bibliometric publications that included an analysis of COVID-19 related papers, 11 reported that men were disproportionately represented as authors of COVID-19 papers. 39,42,46,53,57,58,62,63,67,71,74 There was some variation depending on authorship position; for instance, 2 papers that reported a significant difference in the proportion of women first authors did not report the same effect for last authors. 39,57 For example, Andersen et al 39 compared a sample of 1,893 COVID-19 papers published in medical journals between January and June 2020 with a sample of 85,373 papers published during 2019 in the same journals. The authors estimated that the proportion of COVID-19 papers with a woman first author was 19% lower than for non-COVID-19 papers published in the same journals in 2019, but analysis of last and overall authorship was inconclusive. 39

Included articles that analyzed women’s authorship on “non-COVID-19” papers did not observe the same gendered impact that was observed for COVID-19 papers. For example, Muric et al 58 simultaneously reported both an increase in the expected proportion of women authors for non-COVID-19 preprints posted in medRxiv during the pandemic and a significant decrease in the expected proportion of women authors for COVID-19-related preprints in medRxiv. 58

Two of the 22 bibliometric papers included a proxy of career stage in their analysis. 71,81 The papers documented a disproportionate impact from the pandemic on authorship among early-career researchers. Additionally, 11 of the 22 bibliometric analysis papers included “region/country of origin of authors” in their analysis, 46,53,56,58,62,63,65,66,71,75,76 although it should be noted that certain regions had small sample sizes and there was a high degree of variability in the results reported. For example, 4 of the 11 papers found no significant difference between regions or countries in the pandemic-related authorship gender gap overall. 62,65,66,75 Two of the 11 papers noted some geographical variation during certain time periods that corresponded with lockdown measures, noting no change or smaller changes in the proportion of women authors in some countries in East Asia, including China, Japan,53,58 South Korea, and Taiwan.53 There was some indication that women researchers in low-income regions may have been disproportionally impacted by the pandemic. 53,63 For example, Lerchenmüller et al 53 found that the authorship gender gap trended backward to prepandemic levels in North America and Oceania but not in other continents, with Latin America and Africa remaining furthest away from baseline.

Surveys.

Of the 6 surveys included, 1 was circulated to oncologists, 45 1 to radiologists, 64 and 1 to early-career physician scientists. 44 The remaining 3 surveys included physicians as part of a wider medical staff/faculty sample but did not separately report on data related to physician respondents. 43,52,78

Five of the 6 articles describing survey results found a self-reported reduction in women’s productivity, with women more likely to report decreased time available to engage in scholarly activity than their male counterparts. 43,45,52,64,78 Women completing the surveys reported elevated levels of worry and stress in general, 43,52,78 particularly among those engaged in clinical activities compared with nonclinical researchers 44; increased caregiving responsibilities 43,52,64,78; and reduced time for personal care. 45,52 In particular, 5 articles found that the pandemic had a pronounced impact on early-career researchers, particularly women and those with young children. 43,44,52,64,78

Some of the 6 surveys collected more nuanced demographic information, such as race/ethnicity data 43–45,52,64,78 and gender categories that included gender minority, nonbinary or transgender response options. 43,44,78 However, only 2 articles provided more than descriptive demographic statistics for either of these categories. 43,44 For instance, compared with the other surveys, Doyle et al 44 drew from a more diverse sample (e.g., 63 of 196 [31%] survey respondents identified as Black and 67 of 196 [37%] identified as Hispanic/Latino), finding that early-career physician scientists were significantly less likely to report increased levels of productivity during the pandemic compared with nonphysician PhD researchers. 44 Delaney et al 43 included race and ethnicity in their analysis, although due to reduced sample sizes, they collapsed non-White and non-Asian racial groups into 1 category (“underrepresented in medicine”). The authors found that respondents in the “underrepresented in medicine” group reported increased levels of worry about the impact of COVID-19 on their career and greater consideration of leaving the workforce completely. 43

Qualitative studies.

Only 1 study contained a qualitative component (outside of survey designs that completed qualitative analysis on open-response questions). 41 In their analysis of a virtual panel discussion, Das et al 41 explored the impact of the pandemic on clinical burden, leadership and visibility, work-life integration, mental health, and academic productivity. In relation to academic productivity, the panelists expressed both a sense of frustration over colleagues (typically described as male) commenting that they had increased time during the pandemic to devote to research and a fear that, despite accommodations, it may take women physicians years to catch up to their male counterparts. 41

Strategies to reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups

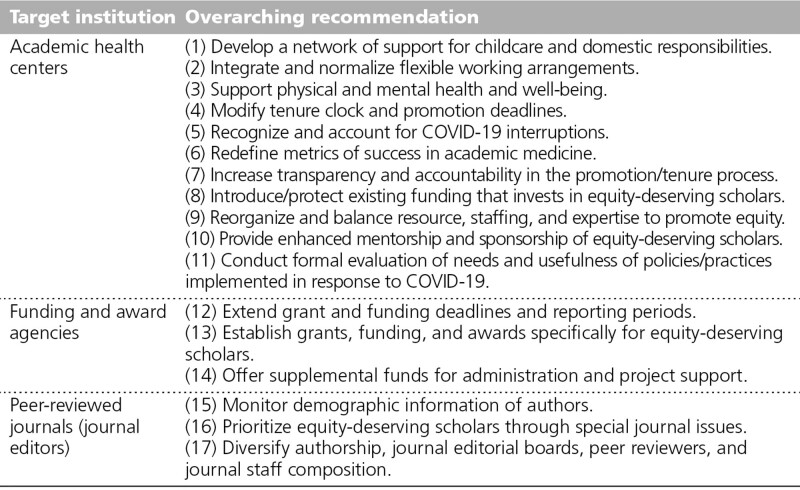

Thirty of the 44 articles (68%) outlined recommendations related to mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on physicians’ scholarly activity. 26,39–41,43,46,47,49–54,57,59,60,62,64,65,67–73,78–81 Overall, recommendations were broadly targeted to 3 institutions: academic health centers, funding and award agencies, and peer-reviewed journal editors. We identified 17 overarching recommendation areas (Table 2). A comprehensive synthesis of individual recommendations with specific examples appears in Supplemental Digital Appendix 4 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B338. The synthesized recommendations represent both specific immediate actions suggested in the wake of COVID-19 and broader recommendations to target preexisting inequities in academic medicine.

Table 2.

Overarching Recommendations Extracted and Consolidated From 30 Papers Included in a Scoping Review Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on the Academic Productivity of Physician Scholars From Equity-Deserving Groups

While the majority of recommendations pertained to cisgender women and mothers, 5 papers discussed the concept of intersecting identities or intersectionality. 50,68,72,77,78 For example, Shamseer et al 68 recommended adopting an “intersectional lens” to identify and explore which populations are experiencing inequities during the pandemic and at which moments of time.

Discussion

Our scoping study found that, as of December 2021, 44 articles had examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic productivity of physicians from equity-deserving groups; however, few of these articles applied an intersectional lens. While all articles included in this scoping study described the gendered impact on academic productivity during the pandemic, few either did or were able to disaggregate data based on other demographic characteristics of women (e.g., Black women, lesbian women, trans women). As such, there are very limited data on this topic outside of the gender binary. Some studies, for example, survey designs, may have collected demographic information such as race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation but may have declined to analyze the findings due to the risk that it could deidentify participants. However, the primary reason for excluding such an analysis was the small sample sizes of demographic categories, which limited the power of these studies to draw conclusions. Difficulty analyzing demographic data through an intersectional lens is not unique to this area of research. As scholarship continues to emerge on methods that might facilitate the intersectional analysis of demographic data, 83,84 there is an opportunity to push for more critical considerations of identity categories when thinking about the differential effects of the pandemic. Although moving toward collecting and analyzing demographic data in a more nuanced way is encouraged, caution is needed so that the collection, analysis, and/or interpretation of data from equity-deserving groups is not mismanaged in a way that fuels prejudices and contributes to discriminatory practices. 85,86

The 22 bibliometric studies included in our review primarily focused on gender, with 2 commenting on age or career stage and 11 including country or region of origin in their analysis. Overall, these studies reported a widening of the gender authorship gap driven by an increase in male-authored research on COVID-19. Gender disparity on COVID-19 research authorship is particularly worrisome given the increased potential for nondiverse teams to reproduce inequity in research, which can ultimately have real-world consequences for how we understand and treat disease (particularly in relation to equity-deserving populations). 63,87 There was also a tentative indication in bibliometric papers that authorship among early-career researchers was disproportionally impacted by the pandemic. 71,81 Additionally, findings from surveys pointed to a differential impact on early-career researchers, particularly mothers and those with young children. 43,44,52,64,78

Our study revealed a lack of attention in the literature on how the pandemic affected other caregiver roles, such as caring for older family members during the pandemic. Multigenerational needs intensified during the pandemic as more families living together caused frictions and psychological stressors to emerge. These caregiver roles may be both gendered and ethnoracially influenced with respect to elderly care. For example, within the United States, attitudes about multigenerational living arrangements during the pandemic varied among African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanic families. 88 With an increasingly aging population, it will be important to identify the barriers and drivers of eldercare on the academic productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups.

Findings regarding geographical region indicated that women’s authorship was impacted globally, but due to the high degree of variability across results, a concrete conclusion about differential impact across regions could not be drawn. It is likely that a variety of factors contribute to the variability observed in the geographical results, as well as in the bibliometric papers more broadly; these factors may include the time period analyzed, the speciality/discipline examined, and the type and quality ranking of the papers authors included in their bibliometric analyses. To draw more definitive conclusions, meta-analytic techniques are warranted; however, these are outside the scope of our current review.

Very few of the included studies focused solely on medical specialties that were particularly impacted by the pandemic from a clinical care perspective. Of the 44 articles, only 2 exclusively focused on emergency medicine. 41,55 Given that critical care medicine has some of the lowest representation of women compared with other medical specialties 89 and there continues to be a dearth of diversity in the internal medicine workforce, 90 future research in these specialties is warranted.

There was also a lack of qualitative studies. Of the 44 studies included in our review, just 1 was qualitative. This was unsurprising given that it typically takes longer to conduct and publish qualitative research and that historically women researchers have used qualitative research methods more than men. 91 A more robust analysis of stalled careers may take longer to become evident and even longer to be reported. We have yet to see the longer-term impact of the pandemic on physician scholars from equity-deserving groups, but our scoping study supported the notion that inequities could be amplified without a conscious effort to mitigate them. Qualitative and/or mixed method research designs could be beneficial to understand this phenomenon, especially in light of the methodological challenges of bibliometric and rapid survey studies.

Our scoping study revealed that system-level changes are needed to address gaps worsened by the pandemic, particularly as we start to move beyond it. If systemic changes are not considered now, we risk losing important gains that were made before the pandemic to create a more equitable environment in academic medicine. Our review identified recommendations in the included studies that targeted academic health centers, funding and award agencies, and journal editors. However, the majority of recommendations focused on women and mothers and did not take into account how intersecting identities of physicians from equity-deserving groups outside of cisgender women impacted academic productivity. Although the breadth of recommendations found was encouraging, implementing solutions through a women/mother lens alone has the potential to reproduce inequities as well as increase the cultural tax on equity-deserving groups. 26,79

Limitations

Despite our efforts to be rigorous, we may have missed some peer-reviewed articles. For example, due to our search strategy and the limitations placed around the definition of academic productivity, we may have missed literature that looked specifically at clinician–educators who might also have expectations of research outputs. Additionally, due to resource limitations, our review did not include books, non-English articles, and publications that are not peer-reviewed, which could have revealed different information. Another limitation is the assumption we made when identifying our population of physician scholars. It was not always obvious when a study was solely focused on physicians, and so we made assumptions based on the journal’s readership (e.g., journals that focused on radiation medicine would be geared toward medical faculty). For surveys, we also included articles if they surveyed medical faculty more broadly but did not specifically parse out physician data. Finally, because we initially anticipated that this work would constitute a rapid review, we did not register a protocol (e.g., via FigShare or Open Science Framework).

Conclusions

Overall, the findings of our review suggested that the preexisting gender gap in authorship of medical peer-reviewed papers has widened during the pandemic. The included bibliometric analyses suggest that the gap in authorship may be particularly pronounced when considering the gender ratio of authors of COVID-19-related submissions and publications. Although we cannot draw a causal link between pandemic restrictions and the increased authorship gender gap, bibliometric findings along with self-reported data returned from faculty surveys point to a disproportionate impact on women’s academic productivity during this period. Our scoping review revealed a lack of data on the impact of the pandemic on the academic productivity of physician scholars from equity-deserving groups other than women.

As a way forward, the pandemic could be viewed as a “rupture,” and as with most ruptures, it presents opportunities for repair by further disrupting the actual status quo. With this rupture, we have an opportunity to work on deeper systemic-level changes more deliberately rather than being reactive or moving too quickly with solutions. Positive changes can be informed by measured research that specifically examines intersectionality and academic productivity both in general and in times of crisis in a way that will not harm the very individuals it purports to help.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Alexandra Morra, MD, Sarah Mackay, and Beth White, MPH, for their contribution to the screening and initial analysis stage of this review.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B338.

Funding/Support: This work was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) as part of a Partnership Engage Grant-COVID-19 Special Initiative (file number: 1008-2020-1141). Our partner for this grant is the Canadian Medical Association (CMA).

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Previous presentations: A previous version of this work was presented at a local education research day for faculty and students, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto; February 10, 2022; Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Contributor Information

Constance LeBlanc, Email: constance.leblanc@dal.ca.

Kinnon R. MacKinnon, Email: kinnonmk@yorku.ca.

Jayna Holroyd-Leduc, Email: jayna.holroyd-leduc@albertahealthservices.ca.

Fiona Clement, Email: fclement@ucalgary.ca.

Brett Schrewe, Email: brett.schrewe@gmail.com.

Heather J. Ross, Email: heather.ross@uhn.ca.

Sabine Calleja, Email: sabine.calleja@unityhealth.to.

Vicky Stergiopoulos, Email: vicky.stergiopoulos@camh.ca.

Valerie H. Taylor, Email: valerie.taylor3@albertahealthservice.ca;valerie.taylor@ucalgary.ca.

Ayelet Kuper, Email: ayelet.kuper@utoronto.ca.

References

- 1.Zimmer K. Gender gap in research output widens during pandemic. The Scientist. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/gender-gap-in-research-output-widens-during-pandemic-67665. Published 2020. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 2.Viglione G. Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here’s what the data say. Nature. 2020;581:365–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staniscuaski F, Reichert F, Werneck FP, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on academic mothers. Science. 2020;368:724–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frederickson M. COVID-19’s gendered impact on academic productivity. https://github.com/drfreder/pandemic-pub-bias/blob/master/README.md. Published May 11, 2020. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- 5.Amano-Patiño N, Faraglia E, Giannitsarou C, Hasna Z. Who is doing new research in the time of COVID-19? Not the female economists. VOX, CEPR Policy Portal. https://voxeu.org/article/who-doing-new-research-time-covid-19-not-female-economists. Published online May 2, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 6.Vincent-Lamarre P, Sugimoto CR, Larivière V. The decline of women’s research production during the coronavirus pandemic. Nature Index. https://www.nature.com/nature-index/news-blog/decline-women-scientist-research-publishing-production-coronavirus-pandemic. Published online May 19, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 7.Myers KR, Tham WY, Yin Y, et al. Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4:880–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson Gabster B, van Daalen K, Dhatt R, Barry M. Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1968–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui R, Ding H, Zhu F. Gender inequality in research productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Man & Serv. Op Man. 2022;24:707–726. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulweiler RW, Davies SW, Biddle JF, et al. Rebuild the academy: Supporting academic mothers during COVID-19 and beyond. PLoS Biol. 2021;19:e3001100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Gender differences in academic medicine: Retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the national faculty survey. Acad Med. 2018;93:1694–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suitor JJ, Mecom D, Feld IS. Gender, household labor, and scholarly productivity among university professors. Gend Issues. 2001;19:50–67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiebinger L, Henderson AD, Gilmartin SK. Dual-Career Academic Couples: What Universities Need to Know . Standford, CA: The Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research, Stanford University; 2008. https://gender.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj5961/f/publications/dualcareerfinal_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Anders SM. Why the academic pipeline leaks: Fewer men than women perceive barriers to becoming professors. Sex Roles. 2004;51:511–521. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edmunds LD OPV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet. 2016;388:2948–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha GL, Lehrer EJ, Wang M, Holliday E, Jagsi R, Zaorsky NG. Sex differences in academic productivity across academic ranks and specialties in academic medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2112404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron P, LeBlanc C, MacLeod A, MacLeod T, O’Hearn S, Simpson C. Women leaders’ career advancement in academic medicine: A feminist critical discourse analysis. Papa R, ed. In: Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43:1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeffer CA. “Women’s work”? Women partners of transgender men doing housework and emotion work. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72:165–183. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly M, Hauck E. Doing housework, redoing gender: Queer couples negotiate the household division of labor. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2015;11:438–464. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tornello SL. Division of labor among transgender and gender non-binary parents: Association with individual, couple, and children’s behavioral outcomes. Front Psychol. 2020;11:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:344–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christmas C, Durso SC, Kravet SJ, Wright SM. Advantages and challenges of working as a clinician in an academic department of medicine: Academic clinicians’ perspectives. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:478–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brubaker L. Women Physicians and the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324:835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al. Collateral damage: How COVID-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:507–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woitowich NC, Jain S, Arora VM, Joffe H. COVID-19 Threatens progress toward gender equity within academic medicine. Acad Med. 2021;96:813–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matulevicius SA, Kho KA, Reisch J, Yin H. Academic medicine faculty perceptions of work-life balance before and since the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2113539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenham C, Smith J, Morgan R. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:846–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Criado Perez C. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. New York, NY: Penguin Random House; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Published March 11, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 33.The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC). Information By Discipline. https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/ibd-search-e. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 34.Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Careers in Medicine: Specialty Profiles. https://www.aamc.org/cim/explore-options/specialty-profiles. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 35.Shaw E, Oandasan I, Fowler N. CanMEDS-FM 2017: A Competency Framework for Family Physicians across the Continuum. 2017. https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/Resources/Medical-Education/CanMEDS-Family-Medicine-2017-ENG.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 36.Davies SW, Putnam HM, Ainsworth T, et al. Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLoS Biol. 2021;19:e3001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.University of Calgary. Employee Equity Census FAQs and the importance of language. https://www.ucalgary.ca/equity-diversity-inclusion/equity-survey-faq. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 38.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersen JP, Nielsen MW, Simone NL, Lewiss RE, Jagsi R. COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. Elife. 2020;9:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cushman M. Gender gap in women authors is not worse during COVID‐19 pandemic: Results from Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:672–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das D, Lall MD, Walker L, Dobiesz V, Lema P, Agrawal P. The multifaceted impact of COVID-19 on the female academic emergency physician: A national conversation. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5:91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeFilippis EM, Sinnenberg L, Mahmud N, et al. Gender differences in publication authorship during covid-19: A bibliometric analysis of high-impact cardiology journals. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e019005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delaney RK, Locke A, Pershing ML, et al. Experiences of a health system’s faculty, staff, and trainees’ career development, work culture, and childcare needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doyle JM, Morone NE, Proulx CN, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on underrepresented early-career PhD and physician scientists. J Clin Transl Sci. 2021;5:e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garrido P, Adjei AA, Bajpai J, et al. Has COVID-19 had a greater impact on female than male oncologists? Results of the ESMO Women for Oncology (W4O) Survey. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gayet-Ageron A, Ben Messaoud K, Richards M, Schroter S. Female authorship of covid-19 research in manuscripts submitted to 11 biomedical journals: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2021;375:n2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ipe TS, Goel R, Howes L, Bakhtary S. The impact of COVID-19 on academic productivity by female physicians and researchers in transfusion medicine. Transfusion. 2021;61:1690–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jorkasky J, Davis M, Lee PP. Potential Impact of COVID-19 disruptions on the next generation of vision scientists. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139:896–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keenan B, Jagsi R, Van Loon K. Pragmatic solutions to counteract the regressive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for women in academic oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:825–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arora VM, Wray CM, O’Glasser AY, Shapiro M, Jain S. Leveling the playing field: Accounting for academic productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:120–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kibbe MR. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on manuscript submissions by women. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:803–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kotini-Shah P, Man B, Pobee R, et al. Work-life balance and productivity among academic faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent class analysis. J Womens Health. 2021;31:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lerchenmüller C, Schmallenbach L, Jena AB, Lerchenmueller MJ. Longitudinal analyses of gender differences in first authorship publications related to COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e045176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewiss RE, Jagsi R. Gender bias: Another rising curve to flatten? Acad Med. 2021;96:792–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mannix A, Parsons M, Davenport D, Monteiro S, Gottlieb M. The impact of COVID-19 on the gender distribution of emergency medicine journal authors. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;55:214–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Misra V, Safi F, Brewerton KA, et al. Gender disparity between authors in leading medical journals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional review. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e051224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mogensen MA, Lee CI, Carlos RC. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on journal scholarly activity among female contributors. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18:1044–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muric G, Lerman K, Ferrara E. Gender disparity in the authorship of biomedical research publications during the COVID-19 pandemic: Retrospective observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e25379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nadkarni A, Mittal L. Can telehealth advance professional equity for women in medicine? Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:1344–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Narayana S, Roy B, Merriam S, et al. Minding the gap: Organizational strategies to promote gender equity in academic medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3681–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ayyala RS, Trout AT. Gender trends in authorship of pediatric radiology publications and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Radiol. 2022;52:868–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nguyen AX, Trinh XV, Kurian J, Wu AY. Impact of COVID-19 on longitudinal ophthalmology authorship gender trends. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259:733–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pinho-Gomes AC, Peters S, Thompson K, et al. Where are the women? Gender inequalities in COVID-19 research authorship. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5:e002922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plaunova A, Heller SL, Babb JS, Heffernan CC. Impact of COVID-19 on radiology faculty: An exacerbation of gender differences in unpaid home duties and professional productivity. Acad Radiol. 2021;28:1185–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prunty M, Rhodes S, Mishra K, et al. Female authorship trends in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2021;79:322–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quak E, Girault G, Thenint MA, Weyts K, Lequesne J, Lasnon C. Author gender inequality in medical imaging journals and the COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology. 2021;300:E301–E307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ribarovska AK, Hutchinson MR, Pittman QJ, Pariante C, Spencer SJ. Gender inequality in publishing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;91:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shamseer L, Bourgeault I, Grunfeld E, et al. Will COVID-19 result in a giant step backwards for women in academic science? J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shimbo M, Nakayama A. The vulnerable cardiologists of the COVID-19 era. Int Heart J. 2021;62:465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spencer S, Burrows C, Lacher SE, Macheledt KC, Berge JM, Ghebre RG. Framework for advancing equity in academic medicine and science: Perspectives from early career female faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med Reports. 2021;24:101576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Squazzoni F, Bravo G, Grimaldo F, Garcia-Costa D, Farjam M, Mehmaniid B. Gender gap in journal submissions and peer review during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. A study on 2329 Elsevier journals. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0257919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Banks L, Randhawa VK, Colella TJF, et al. Cardiovascular physicians, scientists, and trainees balancing work and caregiving responsibilities in the COVID-19 era: Sex and race-based inequities. CJC Open. 2021;3:627–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tso HH, Parikh JR. Mitigating delayed academic promotion of female radiologists due to the COVID pandemic. Clin Imaging. 2021;76:195–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vasti EC, Ouyang D, Ngo S, Sarraju A, Harrington RA, Rodriguez F. Gender disparities in cardiology-related COVID-19 publications. Cardiol Ther. 2021;10:593–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wehner MR, Li Y, Nead KT. Comparison of the proportions of female and male corresponding authors in preprint research repositories before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2020335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams WA, Li A, Goodman DM, Ross LF. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on authorship gender in the Journal of Pediatrics: Disproportionate productivity by international male researchers. J Pediatr. 2021;231:50–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beverly EA. The impact of COVID-19 on womxn in science and osteopathic medicine. J Osteopath Med. 2021;121:525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brown C, Jain S, Santhosh L. How has the pandemic affected women in medicine? A survey-based study on perceptions of personal and career impacts of COVID-19. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle). 2021;2:396–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cardel MI, Dean N, Montoya-Williams D. Preventing a secondary epidemic of lost early career scientists. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on women with children. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:1366–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carr RM, Lane-Fall MB, South E, et al. Academic careers and the COVID-19 pandemic: Reversing the tide. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabe7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cook J, Gupta M, Nakayama J, El-Nashar S, Kesterson J, Wagner S. Gender differences in authorship of obstetrics and gynecology publications during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3:100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rodriguez JK, Guenther EA. What’s wrong with “manels” and what can we do about them. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/whats-wrong-with-manels-and-what-can-we-do-about-them-148068. Published October 4, 2020. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 83.Bauer GR, Churchill SM, Mahendran M, Walwyn C, Lizotte D, Villa-Rueda AA. Intersectionality in quantitative research: A systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM Popul Health. 2021;14:100798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mena E, Bolte G. Intersectionality-based quantitative health research and sex/gender sensitivity: A scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Benjamin R. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge, Oxford, UK: Polity Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 86.O’Neil C. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Senz K. Lack of female scientists means fewer medical treatments for women. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/lack-of-female-scientists-means-fewer-medical-treatments-for-women. Published online February 22, 2022. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- 88.Binette J, Houghton A, Firestone S. Drivers and Barriers to Living in a Multigenerational Household Pre-COVID–Mid-COVID. Washington, DC: AARP Research; 2021. https://www.aarp.org/research/topics/community/info-2020/multigenerational-multicultural-living.html. Accessed August 3, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Parsons Leigh J, de Grood C, Ahmed S, et al. Improving gender equity in critical care medicine: A protocol to establish priorities and strategies for implementation. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ogunwole SM, Dill M, Jones K, Golden SH. Trends in internal medicine faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 1980-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2015205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grant L, Ward KB, Rong XL. Is there an association between gender and methods in sociological research? Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:856. [Google Scholar]